Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hilderley Bettcher

Hilderley Bettcher

Uploaded by

api-162509150Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Sandler, J. Frames of Reference in Psychoanalytic PsychologyDocument89 pagesSandler, J. Frames of Reference in Psychoanalytic PsychologyCarmen Spirescu100% (1)

- 40 Rabbana Duas - Duas With Rabbanah PDFDocument6 pages40 Rabbana Duas - Duas With Rabbanah PDFRoscii RulezNo ratings yet

- Conceptualizing Critical ThinkingDocument19 pagesConceptualizing Critical ThinkingFelipe HollowayNo ratings yet

- Basc-2 Handout FinalDocument2 pagesBasc-2 Handout Finalapi-162509150No ratings yet

- X100V TranslatedDocument4 pagesX100V TranslatedFourthirds Rumors100% (2)

- PROFED 109 ReportDocument17 pagesPROFED 109 Reportwylodene urrizaNo ratings yet

- Reconciling Psychoanalytic Ideas With Attachment Theory: Provided by UCL DiscoveryDocument66 pagesReconciling Psychoanalytic Ideas With Attachment Theory: Provided by UCL DiscoveryAmrAlaaEldinNo ratings yet

- Question 1 Read Article and Do It by Yourself Don't Copy Paste The Answer Please It Is Just A Ideas Write in Your Own WordsDocument9 pagesQuestion 1 Read Article and Do It by Yourself Don't Copy Paste The Answer Please It Is Just A Ideas Write in Your Own WordsMubasshar FarjadNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Students' Motivation: by Annick M. BrennenDocument9 pagesEnhancing Students' Motivation: by Annick M. BrennenJanVen SabellinaNo ratings yet

- EdPsychSpecialIssueReplicationAcceptedVersion PDFDocument35 pagesEdPsychSpecialIssueReplicationAcceptedVersion PDFEdrin rey MulleNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Section On Attachment Theory and PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesIntroduction To The Special Section On Attachment Theory and PsychotherapyMichaeilaNo ratings yet

- Personal Epistemology Research: Implications For Learning and TeachingDocument31 pagesPersonal Epistemology Research: Implications For Learning and TeachingespalditoNo ratings yet

- Q2Document7 pagesQ2technical videosNo ratings yet

- Q2Document7 pagesQ2technical videosNo ratings yet

- Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Valenzuela: A Research Paper SubmittedDocument34 pagesPamantasan NG Lungsod NG Valenzuela: A Research Paper SubmittedNicolai M. CajefeNo ratings yet

- Trevors - APA Belief ChangeDocument47 pagesTrevors - APA Belief ChangeMinh TrangNo ratings yet

- Roberts 2015Document12 pagesRoberts 2015José MoraisNo ratings yet

- Self-Awareness and Personal Growth Theory andDocument22 pagesSelf-Awareness and Personal Growth Theory andvicenteNo ratings yet

- Understanding Psychology Within The Context of The Other Academic DisciplinesDocument30 pagesUnderstanding Psychology Within The Context of The Other Academic DisciplinesKrisia GrahamNo ratings yet

- Christensen Sutton 2011 DraftDocument22 pagesChristensen Sutton 2011 DraftJonn PemNo ratings yet

- Life Span Development: A Six-Unit Lesson Plan For High School Psychology TeachersDocument52 pagesLife Span Development: A Six-Unit Lesson Plan For High School Psychology TeachersmmmmmmNo ratings yet

- Lucariello, 2016Document13 pagesLucariello, 2016carlaj96No ratings yet

- Mindfulness in Schools - Promoting Social and Emotional Learning IDocument34 pagesMindfulness in Schools - Promoting Social and Emotional Learning ILola Ouroburos0% (1)

- Social Science Quarterly - 2022 - Stuckey - A Conceptual Validation of Transformative Learning TheoryDocument16 pagesSocial Science Quarterly - 2022 - Stuckey - A Conceptual Validation of Transformative Learning TheoryBruno Filipe Pereira de SousaNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Guide To The New Brain-Based Teaching (W.W. Norton) A BookDocument13 pagesComprehensive Guide To The New Brain-Based Teaching (W.W. Norton) A BookBASTIAN FELIPE GOMEZ SALASNo ratings yet

- Epistemological Beliefs, School Achievement, and College Major: A Large-Scale Longitudinal Study On The Impact of Certainty BeliefsDocument19 pagesEpistemological Beliefs, School Achievement, and College Major: A Large-Scale Longitudinal Study On The Impact of Certainty BeliefsFrancisco Sebastian KenigNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking: Implications For Instruction: Craig GibsonDocument9 pagesCritical Thinking: Implications For Instruction: Craig GibsonMonica PnzNo ratings yet

- Educational Psychology HudDocument48 pagesEducational Psychology HudKetheesaran LingamNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of The Influence of Emotional Factors On Learning in Physics InstructionDocument20 pagesAn Investigation of The Influence of Emotional Factors On Learning in Physics InstructionNaillah SabaNo ratings yet

- Psychology of LearningDocument14 pagesPsychology of LearningCyprian Eneyo JnrNo ratings yet

- Why Teach Part IIDocument16 pagesWhy Teach Part IInanadadaNo ratings yet

- GS201A - Psychology 1Document5 pagesGS201A - Psychology 1Vinton HaughtonNo ratings yet

- Psychological Foundations of EducationDocument4 pagesPsychological Foundations of EducationTheresaNo ratings yet

- Kernberg, O. F. (2021) - Challenges For The Future of Psychoanalysis. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 81, 281-300Document20 pagesKernberg, O. F. (2021) - Challenges For The Future of Psychoanalysis. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 81, 281-300juan camilo100% (2)

- Pinsof & LebowDocument17 pagesPinsof & LebowCristina TudoranNo ratings yet

- Science Teachers' Beliefs and Practices Issues, Implications and ResearchDocument24 pagesScience Teachers' Beliefs and Practices Issues, Implications and ResearchberumenIINo ratings yet

- Functions and O Rigins o FDocument38 pagesFunctions and O Rigins o FIndahNur MayangSariNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness and PsychologyDocument6 pagesMindfulness and PsychologyGemescu MirceaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Foundations of CurriculumDocument20 pagesUnit 2 Foundations of CurriculumKainat BatoolNo ratings yet

- The Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS) : Psychometric Properties and Associations With Paranoia and Grandiosity in Non-Clinical and Psychosis SamplesDocument12 pagesThe Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS) : Psychometric Properties and Associations With Paranoia and Grandiosity in Non-Clinical and Psychosis SamplesEduardo BrentanoNo ratings yet

- Thomas Lyons - Philosophy of EducationDocument9 pagesThomas Lyons - Philosophy of Educationapi-458243291No ratings yet

- Bab 4 Richard SpringDocument16 pagesBab 4 Richard SpringratulanijuwitaNo ratings yet

- C - Spirituality and Child Development - A Concept Analysis - Smith - McSherryDocument11 pagesC - Spirituality and Child Development - A Concept Analysis - Smith - McSherryDaniela AfonsoNo ratings yet

- Lefaivre PDFDocument13 pagesLefaivre PDFOtra PersonaNo ratings yet

- Frank 1984 The Boulder ModelDocument19 pagesFrank 1984 The Boulder ModelJuan Hernández GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of Scientific RevolutionsDocument4 pagesThe Structure of Scientific RevolutionsAanica VermaNo ratings yet

- Health Psychology: Fall 2016Document10 pagesHealth Psychology: Fall 2016Elber AndrewNo ratings yet

- U03a1 Practitioner-Scholar PaperDocument5 pagesU03a1 Practitioner-Scholar Paperarhodes777No ratings yet

- Belief, Doubt, Critical Thinking, Pedagogy, C. S. Peirce, WellsDocument18 pagesBelief, Doubt, Critical Thinking, Pedagogy, C. S. Peirce, WellsaliciagmonederoNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory in Adult PsychiatryDocument10 pagesAttachment Theory in Adult PsychiatryEsteli189No ratings yet

- 2010 Bro Pie Stah Epist Beliefs Standard For Adapt Learn MLDocument20 pages2010 Bro Pie Stah Epist Beliefs Standard For Adapt Learn MLStella MarquesNo ratings yet

- Contemplation in The Classroom: A New Direction For Improving Childhood EducationDocument31 pagesContemplation in The Classroom: A New Direction For Improving Childhood EducationElena MathewNo ratings yet

- Actividad I Reflexión. El Concepto de PsicologíaDocument3 pagesActividad I Reflexión. El Concepto de PsicologíaDanni EscalonaNo ratings yet

- DIAMANTE, Ma. Joana Manuelle F. - Final ExamDocument23 pagesDIAMANTE, Ma. Joana Manuelle F. - Final ExamJouie DiamanteNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of EducationDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of EducationchenarfarisNo ratings yet

- GENERAL PSYCHOLOGY AND HUMAN LEARNING - Teacher - Co - .KeDocument100 pagesGENERAL PSYCHOLOGY AND HUMAN LEARNING - Teacher - Co - .KeMonydit SantinoNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Educational Psychology and Clinical NeuropsychologyDocument12 pagesThe Relationship of Educational Psychology and Clinical NeuropsychologyJorge BorraniNo ratings yet

- Educational Psychology PSYE1 Individual Variations About This ModuleDocument10 pagesEducational Psychology PSYE1 Individual Variations About This ModuleIdden Keilah CalditNo ratings yet

- Pyschological D-WPS OfficeDocument13 pagesPyschological D-WPS OfficeKurt Brix AndersonNo ratings yet

- Teacher and Moral Development of LearnersDocument8 pagesTeacher and Moral Development of LearnersIVy ChuAhNo ratings yet

- Emerging EpistemologiesDocument140 pagesEmerging EpistemologiescarloscopioNo ratings yet

- Bettcher CV 2013Document2 pagesBettcher CV 2013api-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Learning Task 3Document14 pagesBettcher Learning Task 3api-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Apsy 651 Term PaperDocument13 pagesBettcher Apsy 651 Term Paperapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Interventions To Integrate Adolescents With Tbi Back Into Mainstream ClassroomsDocument18 pagesInterventions To Integrate Adolescents With Tbi Back Into Mainstream Classroomsapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Running Head: Sosi: Preventing Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Sosi: Preventing Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents 1api-162509150No ratings yet

- Summit Youth Mental HealthDocument21 pagesSummit Youth Mental Healthapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Assign 2 Apsy 607Document17 pagesBettcher Assign 2 Apsy 607api-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Apsy 652 Term PaperDocument13 pagesBettcher Apsy 652 Term Paperapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Ethical Decision Making PracticeDocument13 pagesEthical Decision Making Practiceapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Chiasson Learning Task 2Document16 pagesBettcher Chiasson Learning Task 2api-162509150No ratings yet

- 11 - Partial Differential EquationsDocument82 pages11 - Partial Differential EquationsSayemin Naheen50% (4)

- Gear Wheels and Gear Cutting 1977 PDFDocument100 pagesGear Wheels and Gear Cutting 1977 PDFhawktripNo ratings yet

- BS EN 736-3 Valves Terminology - Definition TermsDocument12 pagesBS EN 736-3 Valves Terminology - Definition TermsLuis Daniel ContrerasNo ratings yet

- ASSU Officers Reap Large Stipends: The Stanford DailyDocument8 pagesASSU Officers Reap Large Stipends: The Stanford Dailyeic4659No ratings yet

- 03 - Electrical PowerDocument11 pages03 - Electrical Power郝帅No ratings yet

- Service Delivery Manager Job AdvertnewDocument3 pagesService Delivery Manager Job AdvertnewNauman QureshiNo ratings yet

- Stingray 9.6 User ManualDocument464 pagesStingray 9.6 User Manualmayank1186No ratings yet

- Math: What Is Probability: ? Grade 6Document16 pagesMath: What Is Probability: ? Grade 6Kelly ManganNo ratings yet

- Factor in R PDFDocument4 pagesFactor in R PDFrspecuNo ratings yet

- OmniTurn Manual g3Document210 pagesOmniTurn Manual g3CESAR MTZNo ratings yet

- MPOB PlanningDocument17 pagesMPOB PlanningRicha BabbarNo ratings yet

- BL Form OoclDocument1 pageBL Form OoclWinda RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- The Fentanyl Story: Theodore H. StanleyDocument12 pagesThe Fentanyl Story: Theodore H. StanleyRafael GaytanNo ratings yet

- 22 Finance Lease LessorDocument3 pages22 Finance Lease LessorAllegria AlamoNo ratings yet

- SMC Pneumatics VH Hand Valves - Steven EngineeringDocument9 pagesSMC Pneumatics VH Hand Valves - Steven EngineeringAdrianus AjaNo ratings yet

- $wer, Authority & LegitimacyDocument5 pages$wer, Authority & LegitimacyMohamed RaaziqNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument10 pages1 SMDara aditya NingrumNo ratings yet

- IntelDocument57 pagesIntelanon_981731217No ratings yet

- First Aid RequirementsDocument8 pagesFirst Aid RequirementszayzanNo ratings yet

- Sample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringDocument7 pagesSample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringlisathompsonportlandNo ratings yet

- Simple Present Vs Present ProgressiveDocument5 pagesSimple Present Vs Present ProgressiveSalomeNo ratings yet

- NMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsDocument35 pagesNMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsRaf Lin DrawsNo ratings yet

- Models of PreventionDocument80 pagesModels of Preventionsunielgowda88% (8)

- Common Errors in Truss DesignDocument6 pagesCommon Errors in Truss Designduga110% (1)

- Assignment - Engro CorpDocument18 pagesAssignment - Engro CorpUmar ButtNo ratings yet

- Erytropoiesis Part 1&2 Ninja Nerd ScienceDocument2 pagesErytropoiesis Part 1&2 Ninja Nerd Sciencewati100% (4)

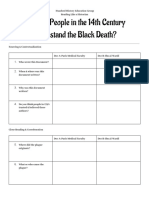

- Understanding The Black DeathDocument2 pagesUnderstanding The Black Deathapi-286657372No ratings yet

- Mood of Deity Worship GDDDocument22 pagesMood of Deity Worship GDDRajkumar GulatiNo ratings yet

Hilderley Bettcher

Hilderley Bettcher

Uploaded by

api-162509150Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hilderley Bettcher

Hilderley Bettcher

Uploaded by

api-162509150Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN

School Psychology and Kuhns Stages of Scientific Enterprise Jaylene Bettcher and Erika Hilderley APSY 635 Advanced History, Theory & Practice in Psychology Dr. John Mueller August 5, 2010

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN School Psychology and Kuhns Stages of Scientific Enterprise Thomas Kuhns 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, continues to challenge the way philosophers, scientists, and professionals alike view science, and more specifically scientific paradigms. Kuhn asserts that there are four stages of scientific enterprise; pre-paradigmatic, normal science, crisis, and revolution. These four stages of scientific

enterprise neither occur simultaneously, nor occur in a linear progression, but instead, they occur in a series of abrupt, incommensurable paradigmatic shifts. Many individuals believe that Kuhns stages of scientific enterprise are applicable to psychology; however, when reviewing Kuhns broad analysis, we found it particularly problematic to relate Kuhns premises to school psychology. Although Kuhn presents a captivating and valuable scheme, the notions and details found in the pre-paradigm, paradigm driven, crisis, and revolution stages do not fit with the hybrid years or thoroughbred years of school psychology. Pre-paradigm According to Kuhn (1962), the first stage of scientific enterprise is the pre-paradigm (prescientific) stage. The pre-paradigm stage encompasses open-ended debates or discussions over fundamentals, whereby there is no consensus on an ideal viewpoint, but rather, individuals adapt an eclectic viewpoint. In his pre-paradigm stage, Kuhn (1962) declares that eclecticism is an asset, which is applicable to school psychology. Many school psychologists have adapted or debated different fundamentals such as behaviourism, clinical psychology, psychiatry, and child development theories. Adhering with the Canadian Code of Ethics (2000), Standard II.9 confirms that psychologists must keep themselves informed within a broad range of important theories, research, techniques, and results and their implications on society, this information may be obtained from literature, peer discussion, and further education. Although Kuhns pre-

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN paradigm stage seemingly fits with school psychology, his final notion that once an individual leaves the pre-paradigm stage, he or she can only practice and/ debate one fundamental is problematic.

Kuhns previous notion is particularly problematic to the discipline of school psychology because it implies that once students inherit the viewpoint of school psychology they are prohibited to use pertinent theories from other fields in their current studies or practice. In accordance with the Canadian Code of Ethics (2000), psychologists are required to immerse themselves in many different theories to maintain competency and gain knowledge and experience in various domains, which is essential when working with a diverse population. Therefore, Kuhns notion not only prohibits school psychologists from learning theories from other fundamentals that may be relevant to their practice, but also, may be considered to be unethical. Normal Science The second stage of scientific enterprise is the normal science (paradigm-driven) stage, which is characterized by rigorous training and a set of received beliefs that prepare students for their future profession (Kuhn, 1962). For example, in order to become a registered school psychologist, it is essential to obtain a pertinent undergraduate degree, followed by a masters degree (some provinces require a PhD), whereby the required perquisites, credit courses, supervised hours, and examinations are successfully completed. These degrees involve rigorous training in a set of received beliefs or standards enforced by an educational institution and/ trained professional that may influence students attitudes, experiences, morals and values. Once again, Kuhns notion of received beliefs seemingly appears to fit with school psychology;

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN however, it becomes problematic when Kuhn declares that received beliefs are designed to control students principles, and furthermore, students minds. Kuhns declaration that rigorous preparation will ensure that received beliefs exert

control over students minds creates a dogmatic approach, whereby received beliefs are not to be disputed or doubted (Kuhn, 1962). Kuhns dogmatic approach is particularly problematic not only to the field of school psychology, but also to graduate students in general. As graduate students, we are encouraged to engage in critical thinking, Fagan (2007) explains that it is important to analyze and evaluate the credibility of sources and statements in every field, including school psychology. In order to make a contribution to the field of school psychology, it is important to draw upon reliable research to gain knowledge in a specific domain, and consequently to be able to apply the knowledge to your practice, as well as subsequent research. School psychology has evolved from, for example, Stanford- Binet scales to Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests, and furthermore, to assessments like the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), which is readily used in present school psychology (Benjamin & Baker, 2004). Without critical thinking these transitions and improvements may not have occurred, and the field of school psychology may be stagnant. Another premise that Kuhn emphasizes in the normal science stage is the premise of mopping up. Kuhns notion of mopping up implies that an anomaly, which is a deviation from the norm, should be disregarded or ignored (Pajares, n.d.). In order for an individual to be diagnosed with a psychological disorder, he or she must meet the minimal criteria as stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IVTR). If the minimal criteria are not met, then the individual is not diagnosed with the disorder; however, that does not imply that the individual is disregarded and forgotten about. For instance,

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN a child may not meet the criteria in the DSM-IV-TR to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder,

but that does not insinuate that it is acceptable to ignore the symptoms. The child should be given recommendations on how to identify symptoms of anxiety, how to cope with symptoms, and how to identify red flags that may occur in the future. In fact, according to Standard 13 of the College of Alberta Psychologists Standards of Practice (2005), a psychologist must provide a client with the opportunity to receive services until the client is either no longer benefiting from the service, or decides to terminate the service due to financial and/or personal reasons. Therefore, Kuhns notion of mopping up an anomaly is an unethical practice for school psychologists. Kuhns notion of mopping up is not his only problematic premise, as a matter of fact, Kuhns premise of puzzle solving may also be problematic in regards to its fit with school psychology. Kuhn (1962) explains that similar to a puzzle, research has a presupposed direction and outcome that is predictable and inflexible. This is problematic to relate to school psychology. When school psychologists assess a child for the first time, it is not always possible to predict a guaranteed outcome. Children are not robots, and they may have a wide range of unforeseen strengths and limitations. In regards to research, Kuhn (1962) affirms that an outcome that deviates from the guaranteed solutions is called an anomaly, and an outcome that persistently deviates from the guaranteed solution is called a crisis. When a crisis occurs it provokes an abrupt paradigm shift to the third stage of scientific enterprise. Crisis As discussed in Fagan & Wises (2007) School Psychology Past, Present, and Future, school psychologys historical development can be divided into the hybrid years and the thoroughbred years. We could consider the divide to have been a crisis of sorts in the eyes of

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN Kuhn leading to a revolution as a new paradigm was introduced. Realizing that the existing establishment of psychology needed to become more stabilized, school psychology was introduced as a professional entity. Consulting psychologists in school boards had lacked certain regulations and guidelines to be recognized as a practicing body previous to the thoroughbred years of 1970-present. It could be said that school psychology was a group without a home (Benjamin & Baker, 2004).

Grouped together with clinical and counselling psychology, school psychology did not emerge as a separate entity until the 1970s. It was then recognized that school practitioners should meet certain criteria in order to administer and practice within the field. Kuhn would argue that this constituted a set of received beliefs within the scientific community and therefore lead to a shift in thinking (Kuhn, 1962). The need for a shift towards a unified body to govern school psychology was evident in the 1950s. As conflicts over sub doctoral practitioners and identity diffusion (Benjamin & Baker, 2004) increased, it was clear that school psychology was at risk of losing momentum and a recognized place in psychology. A conceptual assimilation was made through several conferences, including the noteworthy Thayer Conference with leading psychologists of the time. An awareness of the need to change school psychology from highly setting specific to a broader identity was recommended (Benjamin & Baker, 2004). Again, an identity distinct from educational and clinical psychology was being sought after. Training programs, professional organizations, and specialties began to develop from the growth of school psychology. These provided a stronger more refined understanding of the field and offered professionals an opportunity to have a voice. During this time leading into the thoroughbred years, dissatisfaction with the dominant traditional testing role was found, and

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN greater preference was given towards a stronger involvement in consultation and intervention in

school psychology. Including such practices as consultation, program evaluation, and behaviour management were suggested in various role perception surveys (Fagan & Wise, 2007). Additional distaste with the labelling of students, and the need to test surfaced at this time as well. This time of crisis allowed psychologists an opportunity to discuss discontentment within the field and assess previous theories and determine the present relevance of these. As Kuhn would understand it, the need to retool and move forward to the establishment of a more strengthened and stable identity was presented at this time (2007). A reconstruction of the field from new fundamentals emerged as through the thoroughbred years of school psychology. Revolution A clear shift occurred in school psychology during the late 1960s as discussed earlier; however, it did not replace previous beliefs in the assimilation process, but rather built on existing paradigms. Thomas Kuhns, Scientific Revolution would postulate that the new paradigm leading into the thoroughbred years could solve old anomalies, and provide a better future for school psychology. Ultimately, it would be challenging to argue that all new developments in school psychology rejected those of the older paradigm, as Kuhn would dispute necessary to constitute the shift (Kuhn, 1962). For instance, APA Division 16 Division of School Psychology paved the way for school psychology from the mid 20th Century until the thoroughbred years when the National Association of School Psychologists carried on (Fagan & Wise, 2007). Despite the shift, both groups worked to improve or enhance the regulation of the profession from strictly external to largely internal mechanisms.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN New fundamentals were developed from the hybrid years, including a notable difference between leadership styles. APA and NASP moved from a reactive mode of operation to a more proactive stance. Organizations leading school psychology were no longer accepting guidance from solely state and federal governments, but also working to influence the decisions made by these governing bodies. Furthermore, initiative to create professional regulation with practicing credentials was also being pushed by APA and NASP at this time. Changes to methods and applications of school psychology were in great force with the emergence of the thoroughbred years, as controversy around credentials of professionals within

the field were being questioned, and school psychology morale was declining. From this spurred the need to clearly define the role and educational requirements of school psychologists. Doctoral programs leading to school psychology were on the increase, and the number of nondoctoral school psychologists began to be less of a concern as long-established school-based practices were threatened by the supply of qualified psychologists (Fagan & Wise, 2007). The goal at this time was to maintain high standards of school psychology practice as many areas were pushing to downgrade requirements of school psychology professionals. Rules governing school psychology made a shift at this time to improve the identity of the field. Kuhn explores this shift to be similar to that of a political revolution. It began with a growing sense by members of the psychology community that the existing theories and practices had ceased to adequately meet the issues and concerns posed by school psychology that had in part been created (Kuhn, 1962). Furthermore, the dissatisfaction was not widespread amongst the school psychology population. Those who were less than qualified for the role of school psychologist, and school boards employing those at a reduced salary were not interested in regulating as the repercussions were not favourable from their perspective. These parties sought

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN to defend the old institutional constellation, but were overturned (Fagan & Wise, 2007). Arguably, standards did rise at this point, contrary to Kuhns theory of scientific revolution that understood standards to change as a result of the new paradigm.

It is clear in the literature that the thoroughbred years of school psychology brought about a great deal of change in how the profession operated and was regarded as a whole. New and different things evolved from this shift, and perceptions were formed. As Kuhn (1962) explains, what people see depends both on what they look at and on what their previous visual-conceptual experience has taught them to see. In this instance, textbooks were the authoritative source of the shift between the hybrid years and thoroughbred years of school psychology. Kuhn believed that textbooks ultimately provide little history, and lead to misconstructions of revolution. With that in mind, it should be noted that the piecemeal-discovered facts presented here are our best understanding of how school psychology may fit or not fit into Kuhns broad analysis. Thomas Kuhns 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, presents a captivating and valuable scheme for many of the sciences. However, it is our belief that Kuhns four stages of scientific enterprise; pre-paradigmatic, normal science, crisis, and revolution fit with neither the hybrid years, nor the thoroughbred years of school psychology. If school psychology flawlessly fit with Kuhns broad analysis, school psychology may be deemed unethical in regards to standards from the Canadian Code of Ethics (2000), and school psychology may lose its student centered focus. Contrary to Kuhns premise of incommensurable paradigmatic shifts, we believe that school psychology has evolved through linear transitions. And it is with this linear transition that the field of school psychology will hopefully continue to flourish in many years to come.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY AND KUHN References Baker, D.B. & Benjamin, L.T. (2004). From sance to science: A history of the profession of psychology in America. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

10

Canadian Psychological Association (2000). Canadian code of ethics for psychologists (3rd ed.). Retrieved August 3, 2010, from http://www.cpa.ca/cpasite/userfiles/Documents/Canadian%20Code%20of%20Ethics%20 for%20Psycho.pdf College of Alberta Psychologists (2005). College of alberta psychologists standards of practice. Retrieved August 3, 2010, from http://www.cap.ab.ca/pdfs/HPAStandardsofPractice.pdf Driver-Linn, E. (2003). Where is psychology going? Structural fault lines revealed by psychologists use of Kuhn. American Psychological Association, 58, 269. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.4.269 Facione, P.A. (2006). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. California: California Academic Press. Fagan, T.K., Sachs Wise, P. (2007). School psychology: Past, present, and future (3rd ed). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Kuhn, S. T.(1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Pajares, F. (n.d.). The structure of scientific revolutions. Retrieved from http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/Kuhn.html

You might also like

- Sandler, J. Frames of Reference in Psychoanalytic PsychologyDocument89 pagesSandler, J. Frames of Reference in Psychoanalytic PsychologyCarmen Spirescu100% (1)

- 40 Rabbana Duas - Duas With Rabbanah PDFDocument6 pages40 Rabbana Duas - Duas With Rabbanah PDFRoscii RulezNo ratings yet

- Conceptualizing Critical ThinkingDocument19 pagesConceptualizing Critical ThinkingFelipe HollowayNo ratings yet

- Basc-2 Handout FinalDocument2 pagesBasc-2 Handout Finalapi-162509150No ratings yet

- X100V TranslatedDocument4 pagesX100V TranslatedFourthirds Rumors100% (2)

- PROFED 109 ReportDocument17 pagesPROFED 109 Reportwylodene urrizaNo ratings yet

- Reconciling Psychoanalytic Ideas With Attachment Theory: Provided by UCL DiscoveryDocument66 pagesReconciling Psychoanalytic Ideas With Attachment Theory: Provided by UCL DiscoveryAmrAlaaEldinNo ratings yet

- Question 1 Read Article and Do It by Yourself Don't Copy Paste The Answer Please It Is Just A Ideas Write in Your Own WordsDocument9 pagesQuestion 1 Read Article and Do It by Yourself Don't Copy Paste The Answer Please It Is Just A Ideas Write in Your Own WordsMubasshar FarjadNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Students' Motivation: by Annick M. BrennenDocument9 pagesEnhancing Students' Motivation: by Annick M. BrennenJanVen SabellinaNo ratings yet

- EdPsychSpecialIssueReplicationAcceptedVersion PDFDocument35 pagesEdPsychSpecialIssueReplicationAcceptedVersion PDFEdrin rey MulleNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Section On Attachment Theory and PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesIntroduction To The Special Section On Attachment Theory and PsychotherapyMichaeilaNo ratings yet

- Personal Epistemology Research: Implications For Learning and TeachingDocument31 pagesPersonal Epistemology Research: Implications For Learning and TeachingespalditoNo ratings yet

- Q2Document7 pagesQ2technical videosNo ratings yet

- Q2Document7 pagesQ2technical videosNo ratings yet

- Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Valenzuela: A Research Paper SubmittedDocument34 pagesPamantasan NG Lungsod NG Valenzuela: A Research Paper SubmittedNicolai M. CajefeNo ratings yet

- Trevors - APA Belief ChangeDocument47 pagesTrevors - APA Belief ChangeMinh TrangNo ratings yet

- Roberts 2015Document12 pagesRoberts 2015José MoraisNo ratings yet

- Self-Awareness and Personal Growth Theory andDocument22 pagesSelf-Awareness and Personal Growth Theory andvicenteNo ratings yet

- Understanding Psychology Within The Context of The Other Academic DisciplinesDocument30 pagesUnderstanding Psychology Within The Context of The Other Academic DisciplinesKrisia GrahamNo ratings yet

- Christensen Sutton 2011 DraftDocument22 pagesChristensen Sutton 2011 DraftJonn PemNo ratings yet

- Life Span Development: A Six-Unit Lesson Plan For High School Psychology TeachersDocument52 pagesLife Span Development: A Six-Unit Lesson Plan For High School Psychology TeachersmmmmmmNo ratings yet

- Lucariello, 2016Document13 pagesLucariello, 2016carlaj96No ratings yet

- Mindfulness in Schools - Promoting Social and Emotional Learning IDocument34 pagesMindfulness in Schools - Promoting Social and Emotional Learning ILola Ouroburos0% (1)

- Social Science Quarterly - 2022 - Stuckey - A Conceptual Validation of Transformative Learning TheoryDocument16 pagesSocial Science Quarterly - 2022 - Stuckey - A Conceptual Validation of Transformative Learning TheoryBruno Filipe Pereira de SousaNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Guide To The New Brain-Based Teaching (W.W. Norton) A BookDocument13 pagesComprehensive Guide To The New Brain-Based Teaching (W.W. Norton) A BookBASTIAN FELIPE GOMEZ SALASNo ratings yet

- Epistemological Beliefs, School Achievement, and College Major: A Large-Scale Longitudinal Study On The Impact of Certainty BeliefsDocument19 pagesEpistemological Beliefs, School Achievement, and College Major: A Large-Scale Longitudinal Study On The Impact of Certainty BeliefsFrancisco Sebastian KenigNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking: Implications For Instruction: Craig GibsonDocument9 pagesCritical Thinking: Implications For Instruction: Craig GibsonMonica PnzNo ratings yet

- Educational Psychology HudDocument48 pagesEducational Psychology HudKetheesaran LingamNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of The Influence of Emotional Factors On Learning in Physics InstructionDocument20 pagesAn Investigation of The Influence of Emotional Factors On Learning in Physics InstructionNaillah SabaNo ratings yet

- Psychology of LearningDocument14 pagesPsychology of LearningCyprian Eneyo JnrNo ratings yet

- Why Teach Part IIDocument16 pagesWhy Teach Part IInanadadaNo ratings yet

- GS201A - Psychology 1Document5 pagesGS201A - Psychology 1Vinton HaughtonNo ratings yet

- Psychological Foundations of EducationDocument4 pagesPsychological Foundations of EducationTheresaNo ratings yet

- Kernberg, O. F. (2021) - Challenges For The Future of Psychoanalysis. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 81, 281-300Document20 pagesKernberg, O. F. (2021) - Challenges For The Future of Psychoanalysis. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 81, 281-300juan camilo100% (2)

- Pinsof & LebowDocument17 pagesPinsof & LebowCristina TudoranNo ratings yet

- Science Teachers' Beliefs and Practices Issues, Implications and ResearchDocument24 pagesScience Teachers' Beliefs and Practices Issues, Implications and ResearchberumenIINo ratings yet

- Functions and O Rigins o FDocument38 pagesFunctions and O Rigins o FIndahNur MayangSariNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness and PsychologyDocument6 pagesMindfulness and PsychologyGemescu MirceaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Foundations of CurriculumDocument20 pagesUnit 2 Foundations of CurriculumKainat BatoolNo ratings yet

- The Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS) : Psychometric Properties and Associations With Paranoia and Grandiosity in Non-Clinical and Psychosis SamplesDocument12 pagesThe Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS) : Psychometric Properties and Associations With Paranoia and Grandiosity in Non-Clinical and Psychosis SamplesEduardo BrentanoNo ratings yet

- Thomas Lyons - Philosophy of EducationDocument9 pagesThomas Lyons - Philosophy of Educationapi-458243291No ratings yet

- Bab 4 Richard SpringDocument16 pagesBab 4 Richard SpringratulanijuwitaNo ratings yet

- C - Spirituality and Child Development - A Concept Analysis - Smith - McSherryDocument11 pagesC - Spirituality and Child Development - A Concept Analysis - Smith - McSherryDaniela AfonsoNo ratings yet

- Lefaivre PDFDocument13 pagesLefaivre PDFOtra PersonaNo ratings yet

- Frank 1984 The Boulder ModelDocument19 pagesFrank 1984 The Boulder ModelJuan Hernández GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of Scientific RevolutionsDocument4 pagesThe Structure of Scientific RevolutionsAanica VermaNo ratings yet

- Health Psychology: Fall 2016Document10 pagesHealth Psychology: Fall 2016Elber AndrewNo ratings yet

- U03a1 Practitioner-Scholar PaperDocument5 pagesU03a1 Practitioner-Scholar Paperarhodes777No ratings yet

- Belief, Doubt, Critical Thinking, Pedagogy, C. S. Peirce, WellsDocument18 pagesBelief, Doubt, Critical Thinking, Pedagogy, C. S. Peirce, WellsaliciagmonederoNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory in Adult PsychiatryDocument10 pagesAttachment Theory in Adult PsychiatryEsteli189No ratings yet

- 2010 Bro Pie Stah Epist Beliefs Standard For Adapt Learn MLDocument20 pages2010 Bro Pie Stah Epist Beliefs Standard For Adapt Learn MLStella MarquesNo ratings yet

- Contemplation in The Classroom: A New Direction For Improving Childhood EducationDocument31 pagesContemplation in The Classroom: A New Direction For Improving Childhood EducationElena MathewNo ratings yet

- Actividad I Reflexión. El Concepto de PsicologíaDocument3 pagesActividad I Reflexión. El Concepto de PsicologíaDanni EscalonaNo ratings yet

- DIAMANTE, Ma. Joana Manuelle F. - Final ExamDocument23 pagesDIAMANTE, Ma. Joana Manuelle F. - Final ExamJouie DiamanteNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of EducationDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of EducationchenarfarisNo ratings yet

- GENERAL PSYCHOLOGY AND HUMAN LEARNING - Teacher - Co - .KeDocument100 pagesGENERAL PSYCHOLOGY AND HUMAN LEARNING - Teacher - Co - .KeMonydit SantinoNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Educational Psychology and Clinical NeuropsychologyDocument12 pagesThe Relationship of Educational Psychology and Clinical NeuropsychologyJorge BorraniNo ratings yet

- Educational Psychology PSYE1 Individual Variations About This ModuleDocument10 pagesEducational Psychology PSYE1 Individual Variations About This ModuleIdden Keilah CalditNo ratings yet

- Pyschological D-WPS OfficeDocument13 pagesPyschological D-WPS OfficeKurt Brix AndersonNo ratings yet

- Teacher and Moral Development of LearnersDocument8 pagesTeacher and Moral Development of LearnersIVy ChuAhNo ratings yet

- Emerging EpistemologiesDocument140 pagesEmerging EpistemologiescarloscopioNo ratings yet

- Bettcher CV 2013Document2 pagesBettcher CV 2013api-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Learning Task 3Document14 pagesBettcher Learning Task 3api-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Apsy 651 Term PaperDocument13 pagesBettcher Apsy 651 Term Paperapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Interventions To Integrate Adolescents With Tbi Back Into Mainstream ClassroomsDocument18 pagesInterventions To Integrate Adolescents With Tbi Back Into Mainstream Classroomsapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Running Head: Sosi: Preventing Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Sosi: Preventing Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents 1api-162509150No ratings yet

- Summit Youth Mental HealthDocument21 pagesSummit Youth Mental Healthapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Assign 2 Apsy 607Document17 pagesBettcher Assign 2 Apsy 607api-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Apsy 652 Term PaperDocument13 pagesBettcher Apsy 652 Term Paperapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Ethical Decision Making PracticeDocument13 pagesEthical Decision Making Practiceapi-162509150No ratings yet

- Bettcher Chiasson Learning Task 2Document16 pagesBettcher Chiasson Learning Task 2api-162509150No ratings yet

- 11 - Partial Differential EquationsDocument82 pages11 - Partial Differential EquationsSayemin Naheen50% (4)

- Gear Wheels and Gear Cutting 1977 PDFDocument100 pagesGear Wheels and Gear Cutting 1977 PDFhawktripNo ratings yet

- BS EN 736-3 Valves Terminology - Definition TermsDocument12 pagesBS EN 736-3 Valves Terminology - Definition TermsLuis Daniel ContrerasNo ratings yet

- ASSU Officers Reap Large Stipends: The Stanford DailyDocument8 pagesASSU Officers Reap Large Stipends: The Stanford Dailyeic4659No ratings yet

- 03 - Electrical PowerDocument11 pages03 - Electrical Power郝帅No ratings yet

- Service Delivery Manager Job AdvertnewDocument3 pagesService Delivery Manager Job AdvertnewNauman QureshiNo ratings yet

- Stingray 9.6 User ManualDocument464 pagesStingray 9.6 User Manualmayank1186No ratings yet

- Math: What Is Probability: ? Grade 6Document16 pagesMath: What Is Probability: ? Grade 6Kelly ManganNo ratings yet

- Factor in R PDFDocument4 pagesFactor in R PDFrspecuNo ratings yet

- OmniTurn Manual g3Document210 pagesOmniTurn Manual g3CESAR MTZNo ratings yet

- MPOB PlanningDocument17 pagesMPOB PlanningRicha BabbarNo ratings yet

- BL Form OoclDocument1 pageBL Form OoclWinda RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- The Fentanyl Story: Theodore H. StanleyDocument12 pagesThe Fentanyl Story: Theodore H. StanleyRafael GaytanNo ratings yet

- 22 Finance Lease LessorDocument3 pages22 Finance Lease LessorAllegria AlamoNo ratings yet

- SMC Pneumatics VH Hand Valves - Steven EngineeringDocument9 pagesSMC Pneumatics VH Hand Valves - Steven EngineeringAdrianus AjaNo ratings yet

- $wer, Authority & LegitimacyDocument5 pages$wer, Authority & LegitimacyMohamed RaaziqNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument10 pages1 SMDara aditya NingrumNo ratings yet

- IntelDocument57 pagesIntelanon_981731217No ratings yet

- First Aid RequirementsDocument8 pagesFirst Aid RequirementszayzanNo ratings yet

- Sample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringDocument7 pagesSample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringlisathompsonportlandNo ratings yet

- Simple Present Vs Present ProgressiveDocument5 pagesSimple Present Vs Present ProgressiveSalomeNo ratings yet

- NMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsDocument35 pagesNMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsRaf Lin DrawsNo ratings yet

- Models of PreventionDocument80 pagesModels of Preventionsunielgowda88% (8)

- Common Errors in Truss DesignDocument6 pagesCommon Errors in Truss Designduga110% (1)

- Assignment - Engro CorpDocument18 pagesAssignment - Engro CorpUmar ButtNo ratings yet

- Erytropoiesis Part 1&2 Ninja Nerd ScienceDocument2 pagesErytropoiesis Part 1&2 Ninja Nerd Sciencewati100% (4)

- Understanding The Black DeathDocument2 pagesUnderstanding The Black Deathapi-286657372No ratings yet

- Mood of Deity Worship GDDDocument22 pagesMood of Deity Worship GDDRajkumar GulatiNo ratings yet