Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment Project - Transfer Students

Assessment Project - Transfer Students

Uploaded by

api-212578223Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment Project - Transfer Students

Assessment Project - Transfer Students

Uploaded by

api-212578223Copyright:

Available Formats

Running Head: Transfer Student Engagement

Weaver 1

Transfer Student Engagement Kirby Weaver Wright State University

Dr. DuVivier SAA 7640 December 5, 2012

Running head: Transfer student engagement Literature Review

Weaver 2

As the cost of college tuition rises, students are looking more seriously into ways in which they can cut that cost down. For some students, this means never living on a college campus, and for others, it means attending a community college, before entering a four-year institution. Still, some students begin in a four year institution, realize the expense, and move to another, less costly institution. In addition to cost, there are many students who change schools for a multitude of reasons, sometimes several times before staying in an institution until graduation. All of these students have something in common, and that is that they are considered a transfer students. Those who move from a community college are considered vertical transfers, and those who move from one four year institution to another are considered horizontal transfers (Terris, 2009, p. 1). In both cases, it has become increasingly obvious, that these students struggle more than native students in several areas, namely student engagement, whether that is academic or out-of-class engagement. Today, it is not uncommon to find many more transfer students than what may have been found in the past. Almost half of seniors took at least one course from another school before enrolling at their current institution (Students swirl their way to four-year degrees, 2005, p. 3). More and more students are either changing institutions because they are unhappy or due to financial issues, and due to the stagnant economy, even more late-blooming learners, those who need a change in career or higher degrees, are coming back to school (Colleges catering to growing ranks of transfer, older students, 2009, p. 10). Regardless the reason, the transfer function is of paramount importance to maintaining access to higher education (Laanan, 2001, p. 5). Unfortunately, for many of these students who are attempting to better their lives, evidence from nationally representative samples of students indicates that transferring from one

Running head: Transfer student engagement

Weaver 3

institution to another can have lasting negative consequences (Tobolowsky and Cox, 2012, 389-390). While this can happen for many reasons, it usually stems from the fact that many transfers face new psychological, academic, and environmental challenges and most colleges are either unprepared for this, or do not address what the students go through at all (Laanan, 2001, p. 5). One thing students may face is transfer shock. This is a term that is used to characterize the temporary dip in transfer students academic performance (or grade point average-GPA) in the first or second semester (Laanan, 2001, p.5). For those students who have made the vertical transfer, this dip in performance may be due to the four year institution having more rigorous courses, more course work in general, or because they do not feel comfortable speaking with faculty. In a community college, class size was small and there was more one-on-one interaction with professors, and students felt comfortable in their surroundings. When transferring, the new class size can be intimidating and students may find it difficult to get to know faculty members. In fact, it was found that transfer students reported less interaction with faculty, a lesssupportive campus environment, less active and collaborative learning, and fewer enriching educational experiences (Lipka, 2008, p. 1). This is true for both vertical and horizontal students. With transfers being and ever-growing population of an institution of higher education, it is becoming more and more important for resources to be created and implemented for these students. It seems that most studies in the past have dealt mostly with the students themselves, rather than how institutions cater to them and their needs, but some are quickly realizing that something must be done in order to help these students be successful. It is becoming more obvious that transfer students are a growing but largely neglected group whose needs are as varied as the

Running head: Transfer student engagement

Weaver 4

circumstances that bring them to a college campus in the first place (Colleges Catering to Growing Ranks of Transfer, Old Students, 2009, p.10). An article by Ishitani states that there is even an emerging trend for students who initially enrolled at a two-year institution to transfer to a four year institution to pursue a four-year degree (2008, p. 403-404). That, coupled with the fact that we are in a time where colleges are becoming more and more competitive with each other, not only in what facilities they have, but in how many students they can get, transfers are more popular and important than ever before. Knowing that students will transfer multiple times, it has become obvious that it is not enough to get a transfer, but institutions must work at keeping them as well. Some schools have caught on to this trend, and are working harder than ever to cater to transfer students. Several universities have created transfers success course(s) which are similar to first-year experience courses in that they offer study habits and stress management techniques (Colleges Catering to Growing Ranks of Transfer, Old Students, 2009, p. 10). What they also do, is allow a place for transfer students to make friends and network with others who are in a similar situation as themselves. Other universities are adding advisors, mentor programs, and even wings of residence halls specifically for this population (Colleges Catering to Growing Ranks of Transfer, Old Students, 2009, p.10; Lipka, 2008, p. 1). In order to find much of this information, many colleges and universities are using surveys through The National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE). NSSE is an organization which uses a survey, The College Student Report, which many colleges and universities choose to take part in. This survey tracks the amount of time and effort students put into their studies and other educationally purposeful activities, as well as how the institution deploys its resources and organizes the curriculum and other learning opportunities to get students to participate in

Running head: Transfer student engagement activities (About nsse, 2012). Since 2000, over 1,500 colleges and universities have

Weaver 5

participated, and in 2012 alone, the number is over 550. While NSSE does not evaluate the answers, it seeks to give colleges and universities a chance to measure how they are doing on their own terms. These results are being used all of the time, and help to implement change for transfer students. If some institutions have already started using these results and are creating outreach programs, what will become of the ones that have not, do not plan to, or do not have the resources to do so? Even if they are not recruiting students to transfer there, what if they do? What will happen to the students who have no choice in where they transfer? If every institution is not equipped for these students, what will become of them? How will they succeed? This is a question that every personnel at every higher education institution should be asking. So many transfer students struggle to graduate and some do not graduate at all. They are victims to an unprepared staff, and often times fall through the cracks. For these students, there are few choices, and after their transfer, little time, for them to make mistakes and still graduate on time. For the institutions that are unprepared, they risk losing millions of dollars to students who decide to transfer to a school that is ready to welcome them with open arms. And with this economy, few institutions, especially those that are state funded, can afford to lose such high dollar amounts. These articles discuss the difficulties that transfer students can have engaging, whether socially or academically, upon their transfer. They identify a real need for higher education institutions to create and implement programming that is specific to this growing population. Knowing that high percentages of students will transfer at least once, and knowing that many students are now starting their education at two-year institutions before moving to the four-year

Running head: Transfer student engagement

Weaver 6

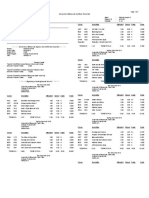

institutions, these articles point out the desperate need for something to be done. Institutions must take action to serve this population. There is much dissatisfaction with the transfer process, and there seems to be few institutions that are doing anything about it. While those that have seem to be off to a good start, there will need to be follow-up done with them in order to find if transfer student engagement and satisfaction have increased. These articles look into what is most important to transfer students, and clearly explain why these students matter. What needs to be done now is for more institutions to come to this realization, and to act on the problems at hand. Quantitative Data One university, Wright State University, chose to use the data from a NSSE survey to compare their native students to transfer students in terms of engagement. Students were asked several questions related to how they interacted with faculty, in the classroom, outside of the classroom, and with other students. Based on the results of this survey, it seems that the native students were more academically engaged than transfer students, with 27%, compared to 21% of transfer students, having prepared two or more drafts of a paper or assignment before turning it in very often. Also, a higher percentage of transfer students had very often come to class without reading or completing assignments, than native students. Touching on the social side, while remaining in the context of academics, 19% of native students, compared to only 17% of transfer students, had worked with classmates OUTSIDE of class to prepare class assignments. Consistently, native students interacted with faculty, in and out of the classroom, more than transfer students. And, when it came to talking to students who were different than themselves, either in terms of race, ethnicity, political views/beliefs, opinions, and personal values, the native students still had higher percentages of participation than transfer student. These findings were

Running head: Transfer student engagement

Weaver 7

consistent with the information presented in many of the articles read, and encouraged farther research into EXACTLY how transfer students felt about their overall experience as a transfer student. It is clear that the transfer students at Wright State University were engaged less, and interviewing individuals would hopefully explain why.

35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Had serious Had serious Worked with faculty conversations with conversations with members on activities students of a different students who are very other than coursework race or ethnicity than different from you in (committees, your own terms of their religious orientation, student life beliefs, political activities, etc.) opinions, or personal values Native Transfer

2009 NSSE Survey Results at Wright State University

Methods & Sample Description A total of three interviews were attempted for this assessment. Two male students and one female were contacted, with ages ranging from 23-25 years of age. The two male students, each at junior status, were the only ones to agree to an interview by the time of the study. One male student was Caucasian and one African-American and each had transferred once in their college careers. These students were chosen based on the fact that they were almost done with their education at the transfer institution, and due to the fact that they transferred from different types of institutions. As the articles that were mentioned earlier touched on both the academic and

Running head: Transfer student engagement

Weaver 8

social engagement of students, I geared my questions towards both aspects of the transfer process. The questions were asked in individual, face-to-face interviews with each student. The students were interviewed separately due to the fact that they had transferred from different institutions. Tom transferred from a junior college to a four-year institution, and John transferred from one four-year institution to another. Assuming the two would have different perspectives, the interviews were conducted individually so that each participant felt free to express his own experiences without fear of judgment. Each student was asked the same 21 questions; however, there were times when follow-up questions were necessary for one student, and not the other. They were asked questions about their feelings toward their previous institution before and after the transfer, as well as the connections they had with faculty, staff, and other students before and after the transfer. These students were also asked what types of programs and activities they would like to see be put in place for all transfer students, whether they had positive or negative transition. As the students were being asked questions, their answers were being typed into a word document so that no information was forgotten and left out. Both students agreed the interview, the recording of their answers, and to their answers being shared. Findings After interviewing each student, it was clear that there was a consensus as to why they chose to leave their previous institution. Both Tom and John left their previous institution due to academic dissatisfaction. Although each feels that they have well established relationships with professors, they have indicated a lack of socialization since transferring to Wright State University. While John was direct about the fact that the institution had no programming to help

Running head: Transfer student engagement

Weaver 9

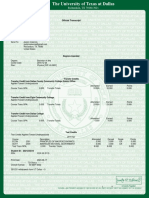

him with the transition, Tom avoided pointing blame. He did indicate that finding friends through his on-campus job was initiated by himself, rather than through programming or another staff member of the institution. Both used phrases like, felt disconnected, overwhelmed, and nervous, and indicated that the faculty and staff did not take part in easing those negative feelings (a chart of these key words used to describe their experiences at Wright State can be found below). Tom did indicate that he felt part of the Wright State community, but also that he spent little time with classmates outside of the classroom. Again, his friends were found through work. John indicated that he would have felt better if the institution had made efforts to make him feel part of the community, and that it would have made a difference in how he viewed the institution overall. It is important to note at what point each student decided to transfer as well. Tom transferred when he was just beginning his program of study, while John was older in age and farther along in his program. This may indicate that the transfer process is easier for students early in their careers, and becomes harder as they move on, due to the fact that students at the new institution have already established relationships and routines.

6 5 4 3 2 1 0 "Disonnected" "Overwhlemed"

Number of Times Key Words were Used

Tom John

"Nervous"

"Unhappy"

Running head: Transfer student engagement Discussion/Conclusion

Weaver 10

Through the interviews conducted with Wright State University students, it is clear that the institution has not done enough outreach for transfer students. As indicated by the results from the NSSE survey and the interviews, some students do not feel as though they are a part of the Wright State community. Both students interviewed struggled with the transfer process and at least one has been left questioning whether he made the right decision in choosing Wright State. Tom and John both felt that more outreach could be done for transfer students, both in the initial steps of the process, and once the transfer was complete. Both stated that there was a sense of isolation and no support through their transition, although Tom was less direct in admitting this. These are in line with articles that have been published and support the idea of having initiatives and continuing programming for transfer students. Based on the articles presented and the interviews conducted, it is clear that more studies should be done at Wright State University, as well as other institutions of higher education, to find how the majority of transfer students feel about the process. It would be wise for institutions to look into programming for transfer students, those that help with the academic side, as well as those that will focus on the social, out-of-the-classroom side of the transfer process. Most students who transfer, do so for multiple reasons, but each of them expects the new institution to do some sort of outreach. I would suggest that programs like the First Year Experience that are in place for freshman, be created for transfer students of all ages. It would also be wise for institutions to have student organizations specifically for transfer students, so they have ample opportunity to meet other students who are going through the same experience as themselves.

Running head: Transfer student engagement References

About nsse. (2012). Retrieved from http://nsse.iub.edu/html/about.cfm

Weaver 11

Colleges catering to growing ranks of transfer, older students. (2009). Community College Week, 21(10), 10. Ishitani, T. (2008). How do transfers survive after transfer shock? A Longitudinal Study of Transfer Student Departure at a Four-Year Institution. Research In Higher Education, 49(5), 403-419. doi:10.1007/s11162-008-9091-x Laanan, F. (2001). Transfer Student Adjustment. New Directions For Community Colleges, (114), 5. Lipka, S. (2008). Survey finds transfer students disengaged, but some colleges are working to change that. Chronicle Of Higher Education, 55(12), A31. Students 'swirl' their way to four-year degrees. (2005). Recruitment & Retention in Higher Education, 19(12), 3-8. Terris, B. (2009). Transfer students are less likely to take part in 'high impact' activities. Chronicle Of Higher Education, 56(12), A19-A20. Tobolowsky, B. F., & Cox, B. E. (2012). Rationalizing neglect: An institutional response to transfer students. Journal Of Higher Education, 83(3), 389-410.

You might also like

- A Sample of Qualitative Research Proposal Written in The APA StyleDocument10 pagesA Sample of Qualitative Research Proposal Written in The APA StyleRobert Holguin Goray100% (3)

- MIT CalendarDocument9 pagesMIT CalendardorkfacexNo ratings yet

- Ethan Yazzie-Mintz (High School Survey of Student Engagement) 2009 - Charting The Path From Engagement To Achievement, ReportDocument28 pagesEthan Yazzie-Mintz (High School Survey of Student Engagement) 2009 - Charting The Path From Engagement To Achievement, Reportluiz carvalho50% (2)

- Mba ProspectusDocument10 pagesMba Prospectusgitehimba100% (1)

- MI Course Catalog 2009-10Document132 pagesMI Course Catalog 2009-10Samuel MorenoNo ratings yet

- Elp 516 Final PaperDocument14 pagesElp 516 Final Paperapi-302275621No ratings yet

- Hoogkamer Transfer CenterDocument14 pagesHoogkamer Transfer Centerapi-208659722No ratings yet

- Practical Research Final Complete 1Document15 pagesPractical Research Final Complete 1Napisa HatabNo ratings yet

- Hesa 522 Praxis-BittnerfishergonzalezshapiroDocument24 pagesHesa 522 Praxis-Bittnerfishergonzalezshapiroapi-650169045No ratings yet

- Changing of College Program: An Analysis of Factors Influencing UST AB Shifters and Transferees (Jareta, Abusmas, Malubay)Document63 pagesChanging of College Program: An Analysis of Factors Influencing UST AB Shifters and Transferees (Jareta, Abusmas, Malubay)Jie Lim Jareta50% (2)

- Work School ConflictDocument23 pagesWork School Conflictboniqua2010No ratings yet

- Running Head: Comparing and Contrasting Orientation Programs 1Document12 pagesRunning Head: Comparing and Contrasting Orientation Programs 1Barry EvansNo ratings yet

- Statement PaperDocument9 pagesStatement Paperapi-404104752No ratings yet

- Synthesis 1Document5 pagesSynthesis 1api-301505398No ratings yet

- Running Head: Sense of Belonging For Running Start StudentsDocument13 pagesRunning Head: Sense of Belonging For Running Start Studentsapi-444220771No ratings yet

- A S Artifact 2 Final Research PaperDocument13 pagesA S Artifact 2 Final Research Paperapi-663147517No ratings yet

- Coun 7132 Multicultural Environments PaperDocument8 pagesCoun 7132 Multicultural Environments Paperapi-245166476No ratings yet

- Unit 4 Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesUnit 4 Literature Reviewapi-310891073No ratings yet

- Description: Tags: CrdbaseDocument41 pagesDescription: Tags: Crdbaseanon-616242No ratings yet

- Challenges and Realizations of First Generation Students Who Navigated Through Transfer Momentum PointsDocument16 pagesChallenges and Realizations of First Generation Students Who Navigated Through Transfer Momentum PointsZrhyNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On AbsenteeismDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On AbsenteeismaflsmceocNo ratings yet

- RESEARCHDocument8 pagesRESEARCHmegodominguez.ewaNo ratings yet

- Pre University Prepared Students A Programme For Facilitating The Transition From Secondary To Tertiary EducationDocument15 pagesPre University Prepared Students A Programme For Facilitating The Transition From Secondary To Tertiary Educationangle angleNo ratings yet

- Hesa 522 Praxis Final PaperDocument16 pagesHesa 522 Praxis Final Paperapi-543192669100% (1)

- The First Year Experience - Intro To SaheDocument8 pagesThe First Year Experience - Intro To Saheapi-212578223No ratings yet

- A Proposal For Scholarship in Colostate UniversityDocument6 pagesA Proposal For Scholarship in Colostate UniversitylinhchingNo ratings yet

- Research Paper of Level of Satisfaction of Working Students and Their Minimum SalaryDocument14 pagesResearch Paper of Level of Satisfaction of Working Students and Their Minimum SalaryErika DomingoNo ratings yet

- Toaz - Info Changing of College Program An Analysis of Factors Influencing Ust Ab Shifters PR - PDFDocument63 pagesToaz - Info Changing of College Program An Analysis of Factors Influencing Ust Ab Shifters PR - PDFMark FlorendoNo ratings yet

- Graduation Rates at US Colleges and UniversitiesDocument10 pagesGraduation Rates at US Colleges and UniversitiesmmozupurNo ratings yet

- Student Interaction Experiences in Distance Learning CoursesDocument17 pagesStudent Interaction Experiences in Distance Learning CoursesIrish ClamuchaNo ratings yet

- Virtual LearningDocument9 pagesVirtual Learningrmm04150% (1)

- RSA Education Between The Cracks ReportDocument74 pagesRSA Education Between The Cracks ReportThe RSANo ratings yet

- Thesis of Ours Edited Final NapoDocument48 pagesThesis of Ours Edited Final NapoVictoria SantosNo ratings yet

- First-Generation College Students PaperDocument80 pagesFirst-Generation College Students Paperapi-404386449No ratings yet

- 6890 Disability Services ProgramDocument8 pages6890 Disability Services Programapi-300396465No ratings yet

- Four Years CollegeDocument60 pagesFour Years CollegeLisaNo ratings yet

- Final PaperDocument15 pagesFinal Paperapi-226892899No ratings yet

- BRM - 1Document22 pagesBRM - 1Satya EswaraoNo ratings yet

- Experiencing College Tuition As Students 1Document10 pagesExperiencing College Tuition As Students 1api-272573140No ratings yet

- 1 of 5 17TH Annual Conference On Distance Teaching and LearningDocument5 pages1 of 5 17TH Annual Conference On Distance Teaching and Learningapi-295665506No ratings yet

- REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE - Revised - EditedDocument9 pagesREVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE - Revised - EditedEric Mark ArrezaNo ratings yet

- Acc Scholarly ReflectionDocument5 pagesAcc Scholarly Reflectionapi-437976054No ratings yet

- Student Satisfaction and Persistence: Factors Vital To Student RetentionDocument18 pagesStudent Satisfaction and Persistence: Factors Vital To Student RetentionAsti HaryaniNo ratings yet

- Student Affairs Role in Involvement On College Campuses Katie Cochran University of Memphis Spring 2015 College Environments Dr. Donna MenkeDocument15 pagesStudent Affairs Role in Involvement On College Campuses Katie Cochran University of Memphis Spring 2015 College Environments Dr. Donna Menkeapi-336844438No ratings yet

- Bettinger 2017 Virtual ClassroomDocument23 pagesBettinger 2017 Virtual ClassroomIulia LazarNo ratings yet

- Writingsample 21Document7 pagesWritingsample 21api-355041101No ratings yet

- Literature Review On Students AbsenteeismDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Students Absenteeismpcppflvkg100% (1)

- Giordano Lizz Hed603 TheorytopracticeDocument7 pagesGiordano Lizz Hed603 Theorytopracticeapi-435887629No ratings yet

- Student Factors Affecting Retention Rate of Bachelor of Science in AccountancyDocument29 pagesStudent Factors Affecting Retention Rate of Bachelor of Science in AccountancyMicka EllahNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Students Academic PerformanceDocument7 pagesThesis On Students Academic Performancekimberlyjonesnaperville100% (2)

- Thomas Thompson Assignment 4Document9 pagesThomas Thompson Assignment 4api-572603171No ratings yet

- RemenickDocument13 pagesRemenickAndrea LapiñaNo ratings yet

- Lit Review 1Document30 pagesLit Review 1api-433424489No ratings yet

- Global Issues GuerreroDocument12 pagesGlobal Issues Guerreroapi-460646871No ratings yet

- International Undergraduate Student Engagement: Implications For Higher Education AdministratorsDocument18 pagesInternational Undergraduate Student Engagement: Implications For Higher Education AdministratorsSTAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Sense of Belonging University WinchesterDocument17 pagesSense of Belonging University WinchesterPilar MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Graded Future Trends ExerciseDocument11 pagesGraded Future Trends Exerciseapi-464438746No ratings yet

- Criticalreading 2Document2 pagesCriticalreading 2api-353827045No ratings yet

- A Time Between: The Full-Time Adult Undergraduate A Sample Qualitative Research Proposal Written in The APA 6 StyleDocument6 pagesA Time Between: The Full-Time Adult Undergraduate A Sample Qualitative Research Proposal Written in The APA 6 StyleNoelle CaballeraNo ratings yet

- Hesa Writing SampleDocument9 pagesHesa Writing Sampleapi-397238352No ratings yet

- Resp Robertson RevDocument6 pagesResp Robertson RevrajrudrapaaNo ratings yet

- Everlyn Ramirez Secondary Education For College Preparation Rhetoric 1312Document8 pagesEverlyn Ramirez Secondary Education For College Preparation Rhetoric 1312api-281782310No ratings yet

- Faculty Development and Student Learning: Assessing the ConnectionsFrom EverandFaculty Development and Student Learning: Assessing the ConnectionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 11-07-12 Financial Aid A Guide For Transfer StudentsDocument7 pages11-07-12 Financial Aid A Guide For Transfer Studentsapi-212578223No ratings yet

- Kirby A Weaver Master ResumeDocument2 pagesKirby A Weaver Master Resumeapi-212578223No ratings yet

- Coco DevDocument9 pagesCoco Devapi-212578223No ratings yet

- The First Year Experience - Intro To SaheDocument8 pagesThe First Year Experience - Intro To Saheapi-212578223No ratings yet

- Office of The Registrar Policies PDFDocument38 pagesOffice of The Registrar Policies PDFAnonymous aJvyrriTWjNo ratings yet

- ACADEMIC MANUAL For DistributionDocument58 pagesACADEMIC MANUAL For DistributionCamilo DominguezNo ratings yet

- Handbook PDFDocument37 pagesHandbook PDFJuan Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- CASS Student Handbook Rev2009Document60 pagesCASS Student Handbook Rev2009Lalaine Agnes PostranoNo ratings yet

- JB U of M Unofficial TranscriptDocument2 pagesJB U of M Unofficial Transcriptapi-347747740No ratings yet

- Una Vida Sin GloriaDocument64 pagesUna Vida Sin Gloriafelixpujols007No ratings yet

- Academic Catalog Day SchoolDocument475 pagesAcademic Catalog Day SchoolPan DorymNo ratings yet

- ISSA - Course - Catalog - Become A Personal TrainerDocument34 pagesISSA - Course - Catalog - Become A Personal TrainerMohammad Reza SayarNo ratings yet

- TWNDBJRNDocument5 pagesTWNDBJRNJosie ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Student Handbook AY2021-22 (26 Aug)Document28 pagesStudent Handbook AY2021-22 (26 Aug)Oscar RomainvilleNo ratings yet

- Medina Lisa Resume MiracostaDocument2 pagesMedina Lisa Resume Miracostaapi-255216529No ratings yet

- Fit With Cambrie Meal PlanDocument566 pagesFit With Cambrie Meal PlanAbigail Rautenbach0% (1)

- Berklee Online - Master's and Bachelor's Music Degrees, Certificates, and CoursesDocument17 pagesBerklee Online - Master's and Bachelor's Music Degrees, Certificates, and CoursesLomon SamNo ratings yet

- Manual of OperationsDocument67 pagesManual of OperationsHana Tsukushi100% (1)

- OfferLetter - Nicolas Andree Castro Olivares - Tayrona Australian Education - 08062023Document9 pagesOfferLetter - Nicolas Andree Castro Olivares - Tayrona Australian Education - 08062023ausnicolascoa99No ratings yet

- Bachelors Student Handbook - ALUDocument30 pagesBachelors Student Handbook - ALUPol MilNo ratings yet

- Advisor Approval FormDocument1 pageAdvisor Approval FormKate D'AmarioNo ratings yet

- EngDocument16 pagesEngAbohfu Venant ZinkengNo ratings yet

- SCRIBD DOCUMENTS TRANSFRERRED TO HOMEWORK FOX @ LINK:http://homeworkfox.com/user/8296/ASHFORD UNIVERSITY ONLINE GRADUATE LEVEL COURSE HOMEWORK HELPFOR ASHFORD UNIVERSITY ONLINE COURSES IN EDU, OMM AND BUS..GRADE A PAPERS AShford Homework Help includes EDU MATLT Program at Ashford Organizational Mgmt program OMM and BUS PROGRAM COURSE LISTINGS AND GRADES FOR KEITH QUARLES WITH DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE/TRANSFERRED TO HOMEWORKFOX.COM @ THE FOLLOWING LINK:http://homeworkfox.com/user/8296/Document5 pagesSCRIBD DOCUMENTS TRANSFRERRED TO HOMEWORK FOX @ LINK:http://homeworkfox.com/user/8296/ASHFORD UNIVERSITY ONLINE GRADUATE LEVEL COURSE HOMEWORK HELPFOR ASHFORD UNIVERSITY ONLINE COURSES IN EDU, OMM AND BUS..GRADE A PAPERS AShford Homework Help includes EDU MATLT Program at Ashford Organizational Mgmt program OMM and BUS PROGRAM COURSE LISTINGS AND GRADES FOR KEITH QUARLES WITH DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE/TRANSFERRED TO HOMEWORKFOX.COM @ THE FOLLOWING LINK:http://homeworkfox.com/user/8296/keith_quarlesNo ratings yet

- GmbaDocument48 pagesGmbaPrahant KumarNo ratings yet

- 2015-16 Fas Student HandbookDocument430 pages2015-16 Fas Student HandbookDaniel LuNo ratings yet

- BHCC College Catalog 2005 06 PDFDocument191 pagesBHCC College Catalog 2005 06 PDFbrooklynsnowNo ratings yet

- Ucat SCMNS PDFDocument58 pagesUcat SCMNS PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- BS in MLS Curriculum Transfer Students Current 3Document1 pageBS in MLS Curriculum Transfer Students Current 3Abraham MichaelNo ratings yet

- Sophia Partnership-Guide DigitalDocument6 pagesSophia Partnership-Guide DigitalmrNo ratings yet

- International Application For Admission and Scholarship PacketDocument15 pagesInternational Application For Admission and Scholarship Packetrinchen mingchungNo ratings yet

- Credit Transfer Policy Annex 1 SRR P-1105-2v1905 0Document4 pagesCredit Transfer Policy Annex 1 SRR P-1105-2v1905 0Purusattam RoyNo ratings yet