Professional Documents

Culture Documents

03.a Failure of The No-Arbitrage Principle

03.a Failure of The No-Arbitrage Principle

Uploaded by

Liou KevinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

03.a Failure of The No-Arbitrage Principle

03.a Failure of The No-Arbitrage Principle

Uploaded by

Liou KevinCopyright:

Available Formats

A Failure of the No-Arbitrage Principle

Botond K oszegi Department of Economics University of California, Berkeley Krist of Madar asz Department of Economics University of California, Berkeley

M at e Matolcsi R enyi Institute of Mathematics Budapest, Hungary July 2007

Abstract Underlying the principle of no arbitrage is the assumption that markets eliminate any opportunity for risk-free prots. In contrast, we document a pricing mistake by a $200 million company that allowed investors a guaranteed return of 25.6% in a few days, and that resulted in less than $60,000 being invested into exploiting the opportunity.

Introduction

The principle of no arbitragethat prices cannot allow for risk-free net protsplays a key role in the understanding of prices and price movements in nancial markets, being a central component of such fundamental concepts and theories as the ecient-markets hypothesis, arbitrage pricing theory, and option pricing. The principle does not require that every individual in the market be fully rational and prefer more money to less, but it does require that suciently many motivated decisionmakers with access to sucient resources notice any possible mispricing, put a lot of pressure on it, and quickly eliminate it. Questioning part of this argument, recent research on the limits of arbitrage has emphasized that even if investors notice a mispricing, they may not be able to or want to fully correct it.1 But very little research has addressed the other necessary ingredient

K oszegi thanks the Central European University for its hospitality while some of this work was completed. Matolcsi thanks OTKA grant PF64061 for nancial support. 1 For a summary of this research and a detailed discussion of arbitrage, see for instance Shleifer (2000). For examples of theories of limited arbitrage, see De Long, Shleifer, Summers, and Waldmann (1990) and Shleifer and

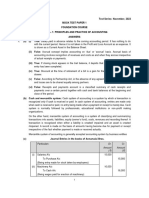

of the no-arbitrage principle, that suciently many people will notice and exploit mispricing when doing so allows for large riskless prots independently of ones subjective beliefs. In this note we document an instance in which one rm, gambling monopoly Szerencsej at ek Rt. (SzjRt) of Hungary, created a striking arbitrage opportunity against itself, and survived it with ying colors. In one week of peak demand, SzjRts pricing structurewhich was widely read public informationallowed an arbitrage opportunity very similar to those underlying derivative pricing: bettors could construct a portfolio of correlated assets leaving them perfectly hedged, and make a return of over 25% in a couple of days.2 Figure 1 shows SzjRts weekly prots in 1998 from the game in which arbitrage was possible. The arbitrage opportunity occurred in Week 26, in which SzjRt posted the years highest prots from the game! Clearly, even in this ideal setting for arbitrage, the hypothesis that suciently many individuals notice and exploit mispricing fails. Indeed, we calculate that the (very conservative) upper bound on the amount of money that could have been placed as part of an arbitrage strategy is 12,511,000 HUF (about $59,500 at the time), a mere 5.46% of revenue and 11% of payouts from that single game that week. This is so little money that it must have been a minor headache for SzjRt that week. In fact, if it had any other reason for the pricing structure in placefor instance, to make the game more exciting in a week of peak demandthe company may, instead of going bankrupt as the principle of no arbitrage predicts, have made money on this mispricing.

Some Background

Szerencsej at ek Rt. may be an unusual target for arbitrage, but if anything it is a safer bet for investors than most targets. The company is Hungarys state-owned monopoly provider of numberdraw games and sports bets. With revenue of just under 44 billion HUF (about $210 million) in 1998, it is one of the largest companies in the country. Its prots are absorbed into, and its

Vishny (1997). Lamont and Thaler (2003) give examples of very large deviations from the law of one price that were apparently widely known; they argue that the limits of arbitrage were so great that even large mispricing could not be corrected. 2 Interested readers caninstead of reading our explanation belowtry to nd the arbitrage opportunity themselves by opening and looking at (our translation of) what gamblers saw. We conjecture that even with the substantial benets of a very high IQ and of the knowledge that there is an opportunity, readers will not nd it immediately apparent. In fact, one author, although he was a regular player of the game at the time, failed to spot the opportunity.

100 50 0 1 -50 -100 -150 Week (Starting January 1, 1998) 6 11 16 21 26 31 36 41 46 51

Figure 1: Szerencsej at ek Rts Weekly Prots From the Tippmix Game in 1998. (Note: The $-HUF exchange rate at the time was 210.) potential losses are backed by, the state budget. Because SzjRt therefore has no option to go bankrupt, its promises to pay are more credible than those of most private companies, regarding which the question of arbitrage usually arises. In addition, while SzjRt reserves the right to cancel sports bets, the 1991 Act on the Organization of Gambling Operations allows it do so only when the actual sports event is canceled or there is a case of documentable corruption. Because the arbitrage opportunity is based on matches in soccers biggest international event, the World Cup, there is essentially no chance that any of these would happen. The relevant details of the game in question, Tippmix, were public information in any sense of the word commonly understood in economics and nance. The betting opportunities were published in SzjRts sports-gambling newsletter Sportfogd as (circulation: 100,000), the sports daily Nemzeti Sport (which is read by most sports fans), on Teletext, at several hundreds of SzjRt outlets, and at almost all post oces in Hungary. Even considering how many people actually read the informationa measure that seems stricter than that typically applied for the publicness of informationdetails of Tippmix were widespread. Conservative estimates of SzjRt indicate that an

Profits (Million HUF)

# 8. 9.

game Chicago-Dallas Ivanchuk-Kramnik

former 1.50 3.20

tie 3.00 1.50

latter 4.00 3.65

Table 1: Two Bettable Partitions from Week 27, 1998 average of at least 10,000 people played each week. Since revenue in our week of interest was way above the years average (229,032,600 HUF versus 111,128,321 HUF), it is likely that the actual number of players was higher still. Furthermore, while Tippmix was targeted at a general audience, unpublished market studies of SzjRt suggest that it drew much interest from the wealthier, collegeeducated part of the population.

The Opportunity

The arbitrage opportunity we analyze arose in the Tippmix game oered by SzjRt. Tippmix is a relatively complicated sports gambling game, as it gives individuals substantial exibility to make combined bets. For example, in Week 27 in 1998 gamblers could combine bets on the outcomes of the Ivanchuk-Kramnik chess match in Germany and the Chicago-Dallas soccer match in the United States. Table 1 shows part of the two lines corresponding to these bets in the list of 114 possible bets that week. Each outcome of each match has an odds specifying the amount of money one can win when betting on that outcome alone. For example, the odds for Dallas winning the Chicago-Dallas game was 4, meaning that if an individual placed a singleton bet of 1HUF on this outcome and she got it right, she would have received 4HUF. If a person makes a combined bet on multiple matches, she wins money only if all her guesses are right; but in that case, the relevant multiplier is the product of the odds of the individual outcomes. Hence, for example, if someone put a double bet on Dallas and Ivanchuk winning and was right, she would have received 4 3.2 = 12.8 times her wager. The fact that bettors could place combined bets does not in itself mean that arbitrage opportunities easily arise. The reason this was possible is that in Week 26 in 1998, Szerencsej at ek 4

# 8. 9.

game Ivanchuk1-Kramnik1 Ivanchuk2-Kramnik2

former 3.20 3.20

tie 1.50 1.50

latter 3.65 3.65

Table 2: Hypothetical Example with Logically Connected Bets Rt. allowed gamblers to combine multiple bets on the same sports event. To illustrate the implications in an extreme example, suppose that bettors could combine two logically identical bets on the outcome of the actual Ivanchuk-Kramnik match, as illustrated in the hypothetical Table 2. Then, to win 1HUF if Ivanchuk wins, it suces to place a double wager of 1/(3.2 3.2) on both Ivanchuk1 and Ivanchuk2 winning (recall that the odds from dierent bets are multiplied). Extending this logic, to win 1HUF for any outcome of the match, it suces to spend 1/(3.2 3.2) + 1/(1.5 1.5) + 1/(3.65 3.65) 0.62HUF. Hence, while making a singleton bet cannot generate riskless prot, this double bet yields a whopping riskless return of 61%! Why does this work? Intuitively, if a combined bet is drawn from dierent matches, to make sure one wins one must bet on all combinations of outcomes. But if bets are logically related because they derive from the same match, it may take much fewer wagers to cover all possible outcomes of the match. The actual arbitrage opportunity was of course more complicated because the possible related bets were not identical, and because SzjRt had restrictions in place on the minimum number of bets that had to be involved in a combined bet. The most protable balanced arbitrage strategy where the amount of winnings is risklessis based on the Argentina-Croatia game in Week 26.3 Gamblers could bet on whether the game would be a win, tie, or loss for Argentina, as well as on what the score would be (0-0, 1-0, 0-1, etc., or other). Any exact score fully determines whether the game is a win, tie, or loss, so the two bets are very closely linked logically. To construct an arbitrage, we combine each score with the appropriate summary outcome, and the other score with all three possibilities, covering all possible outcomes of the match. A diculty is that for these highly arbitrageable bets gamblers had to place at least ve-fold combined bets. But it just

There were also two less protable balanced arbitrage strategies and of course countless non-balanced arbitrage strategies.

3

so happens that SzjRt allowed another pair of related bets: whether Yugoslavia would win, tie, or lose its match with the United States, and whether it would win by at least 2 goals, 1 goal, or not win. As our fth (or possibly sixth) bet, we use the number of goals scored by either Suker (a Croat) or Batistuta (an Argentine) or both, since if either Croatia or Argentina is scoreless, that automatically implies their player does not score. The details of this arbitrage strategy are in the appendix, where we show that it produced a risk-free return of 25.6% in just a few days.4

Evidence on Responses

Even based on aggregate evidence, it is immediately apparent that exploitation of the arbitrage opportunity could not have been widespread. As shown in Figure 1, SzjRt realized a record prot from Tippmix during the week in question. While this record prot was partly due to record demand for Tippmix, it was also due to a 41% prot rate that was well above the years average of 26%. In contrast, if everyone had followed the most protable balanced arbitrage strategy, then SzjRt would have realized a loss of 25%. Beyond these aggregate measures, we can provide a rough upper bound on the amount of money that could have been invested into arbitrage strategies. For each possible bet, we have obtained from SzjRt the total amount of money that was spent in wagers involving that bet (including singleton bets and combined bets of all sizes). Hence, we exploit that certain bets had to be involved in any arbitrage strategy. As we show in the appendix, any arbitrage strategy must involve bets that are logically connected. In Week 26 there were exactly three matches on which multiple bets were allowed: the Yugoslavia-US, Argentina-Croatia, and Germany-Iran matches of the World Cup. Based on simple but tedious calculations, we show in the appendix that any arbitrage had to involve the Argentina-Croatia match and at least one of the other two matches. Based on this very rough consideration, we get a very low upper bound for the amount of arbitrage money in Tippmix. Consumers spent 5,235,000 HUF ($25,000) betting on whether GerImplementing an arbitrage strategy involved modest but non-trivial transaction costs because it required lling out many tickets. For example, implementing the most protable balanced arbitrage above would have required lling out 116 tickets, which we estimate would have taken one to two hours. This work was, however, largely a xed cost: once the tickets were lled out, a bettor could increase the stakes of the bet in principle without limit.

4

many wins by 2 goals, 1 goal or does not win against Iran, and 7,276,000 HUF ($34,500) betting on whether Yugoslavia wins by 2 goals, 1 goal or does not win against the US. This means that no more than 12,511,000 HUF ($59,500), a mere 5.46% of the wagers in Tippmix, was spent on arbitrage strategies. Furthermore, our data suggests that much or most of even this money may not have been coming from arbitrageurs. In Week 26 the amount placed on Belgium wins its soccer match by 2 goals/1 goal/does not win was 8,902,000 HUF ($42,500)higher than the amount placed on either arbitrage bet of the same form. Similarly, in nearby weeks where there was no arbitrage opportunity, the amount of money placed on bets of the form Team X wins its soccer match by 2 goals/1 goal/does not win varied between 3% and 10% of revenue. A combined 5.46% on two such bet is on the low side of this range of non-arbitrage demand.

Conclusion

Our note is only the case study of a single instance where market participants failed to exploit a very protable arbitrage opportunity. In itself, it answers neither why most individuals failed to spot the opportunity, nor how common unexploited arbitrage opportunities are. To gain traction on these questions, a systematic analysis of a large number of arbitrage opportunities would be useful.

References

De Long, J. B., A. Shleifer, L. H. Summers, and R. J. Waldmann (1990): Noise Trader Risk in Financial Markets, Journal of Political Economy, 98(4), 703738. Lamont, O., and R. H. Thaler (2003): Can the Stock Market Add and Subtract? Mispricing in Tech Stock Carve-Outs, Journal of Political Economy, 111(2), 227268. Shleifer, A. (2000): Clarendon Lectures: Inecient Markets. Oxford University Press. Shleifer, A., and R. W. Vishny (1997): The Limits of Arbitrage, Journal of Finance, 52(1), 3555.

You might also like

- Swot AnalysisDocument21 pagesSwot AnalysisEvan SenNo ratings yet

- Investment Analysis NotesDocument15 pagesInvestment Analysis NotesManikandan PitchumaniNo ratings yet

- Pay Slip: For The Month of September 2019Document1 pagePay Slip: For The Month of September 2019mustafaNo ratings yet

- Week#8 Lecture Examples-Chp6 Questions PDFDocument9 pagesWeek#8 Lecture Examples-Chp6 Questions PDFLucyNo ratings yet

- Solution Advanced Accounting 11ed Chp4Document45 pagesSolution Advanced Accounting 11ed Chp4Bayoe Ajip82% (11)

- The St. Petersburg ParadoxDocument5 pagesThe St. Petersburg ParadoxLance Lot100% (1)

- A Method For Winning at Lotteries: SSRN Electronic Journal January 2017Document25 pagesA Method For Winning at Lotteries: SSRN Electronic Journal January 2017Ognjen OzegovicNo ratings yet

- Win LotteryDocument21 pagesWin LotteryPoliCamNo ratings yet

- Beating The Odds: Arbitrage and Wining Strategies in The Football Betting MarketDocument21 pagesBeating The Odds: Arbitrage and Wining Strategies in The Football Betting MarketAlazar EsayasNo ratings yet

- Why Are Gambling Markets Organised S O D Ifferently From Financial M Arkets?Document25 pagesWhy Are Gambling Markets Organised S O D Ifferently From Financial M Arkets?joeNo ratings yet

- AStrategyForWinningAtLotteries GTE Ver2Document25 pagesAStrategyForWinningAtLotteries GTE Ver2shoodelor88No ratings yet

- The Suntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines, The London School of Economics and Political Science, Wiley EconomicaDocument11 pagesThe Suntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines, The London School of Economics and Political Science, Wiley EconomicasjbladenNo ratings yet

- The Fibonacci Strategy Revisited: Can You Really Make Money by Betting On Soccer Draws?Document7 pagesThe Fibonacci Strategy Revisited: Can You Really Make Money by Betting On Soccer Draws?RobsonCorrêaNo ratings yet

- Manuscript - FinalDocument14 pagesManuscript - FinalTenebrae LuxNo ratings yet

- Efficiency and Profitability in Exotic Bets PDFDocument11 pagesEfficiency and Profitability in Exotic Bets PDFjesseNo ratings yet

- Finding Good Bets in The Lottery, and Why You Shouldn't Take ThemDocument35 pagesFinding Good Bets in The Lottery, and Why You Shouldn't Take ThemmsafrikkaNo ratings yet

- WRAP Walker Twerp572Document38 pagesWRAP Walker Twerp572RIDZWAN ABDUL RAZAKNo ratings yet

- 01 - (ARTICLE) Arbitrage Opportunities in Sports Betting MarketsDocument45 pages01 - (ARTICLE) Arbitrage Opportunities in Sports Betting MarketsPaul bocuseNo ratings yet

- 8887 New Goods and Economic Growth Evidence From Legalized GamblingDocument24 pages8887 New Goods and Economic Growth Evidence From Legalized GamblingrbhagatNo ratings yet

- Game StopDocument10 pagesGame Stopgabrielapashkunova.18No ratings yet

- Optimal Betting Strategy Win Draw LossDocument5 pagesOptimal Betting Strategy Win Draw LossZoranMatuško0% (1)

- New Investment ParadigmDocument3 pagesNew Investment ParadigmJeremy HeffernanNo ratings yet

- 10 Golden Rules To Become RichDocument39 pages10 Golden Rules To Become RichAlmas K ShuvoNo ratings yet

- Casino Gambling As Local Growth GeneratiDocument44 pagesCasino Gambling As Local Growth GeneratiNG COMPUTERNo ratings yet

- Microecon Game TheoryDocument21 pagesMicroecon Game TheoryAAA820No ratings yet

- Optimal Betting Strategy Win Draw LossDocument6 pagesOptimal Betting Strategy Win Draw Losskasjdhasd sldhasdNo ratings yet

- A Playground For RobotsDocument4 pagesA Playground For RobotsTim PriceNo ratings yet

- Betting Pricing From Mathematical PerspectiveDocument45 pagesBetting Pricing From Mathematical PerspectiveCostache SorinaNo ratings yet

- ECO Ass 3Document19 pagesECO Ass 3Khushi ParmarNo ratings yet

- ECO Ass 3Document18 pagesECO Ass 3Khushi ParmarNo ratings yet

- Full 02-19 04Document3 pagesFull 02-19 04Helppo HeikkiNo ratings yet

- A Primer On Hedge FundsDocument10 pagesA Primer On Hedge FundsOladipupo Mayowa PaulNo ratings yet

- Research Notes: The Economic Role of SpeculationDocument10 pagesResearch Notes: The Economic Role of SpeculationMarius Constantin CoceaNo ratings yet

- El Panorama Reciente de La Crisis y El FEDDocument3 pagesEl Panorama Reciente de La Crisis y El FEDriemmaNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Game Theory and Its Insurance ApplicationsDocument24 pagesCooperative Game Theory and Its Insurance ApplicationsJorge MoyaNo ratings yet

- The Favourite-Longshot Bias Across Different Classes of Horse Races: Evidence From The 2003 UK Flat Turf SeasonDocument34 pagesThe Favourite-Longshot Bias Across Different Classes of Horse Races: Evidence From The 2003 UK Flat Turf Seasontrdn55No ratings yet

- Do Leveraged ETF Increase VolatilityDocument6 pagesDo Leveraged ETF Increase VolatilitysaugustessNo ratings yet

- Researchpaper2022 C Catheline Gamestop A Short SqueezeDocument63 pagesResearchpaper2022 C Catheline Gamestop A Short SqueezeDark PhantomNo ratings yet

- Limits of ArbitrageDocument106 pagesLimits of ArbitragealexandergirNo ratings yet

- Strategy Zim 0221 CtaDocument63 pagesStrategy Zim 0221 CtaDAVID ISAZA CADAVIDNo ratings yet

- Don't Shoot The MessengerDocument3 pagesDon't Shoot The MessengerTim PriceNo ratings yet

- Schildershoven Finance - The Tantalus TormentsDocument4 pagesSchildershoven Finance - The Tantalus TormentsArnaud InsingerNo ratings yet

- Bondeee A RenkoDocument46 pagesBondeee A RenkoTurcan Ciprian SebastianNo ratings yet

- Kelly CriterionDocument14 pagesKelly Criterionmustafa-ahmedNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy1.2Document567 pagesMonetary Policy1.2Eric GarrisNo ratings yet

- Arbitrage Strategy: February 2010Document3 pagesArbitrage Strategy: February 2010Gyanesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Financial Market and InstitutionsDocument6 pagesFinancial Market and InstitutionsTofazzal HossainNo ratings yet

- Be AfraidDocument3 pagesBe AfraidTim PriceNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Derivatives: (1) ObjectiveDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Derivatives: (1) ObjectivePratik KillaNo ratings yet

- (Smith Suchanek Williams, Econometrica 1988) Bubbles, Crashes and Endogenous Expectations in Experimental Asset MarketsDocument34 pages(Smith Suchanek Williams, Econometrica 1988) Bubbles, Crashes and Endogenous Expectations in Experimental Asset MarketsSaad TateNo ratings yet

- English Essay 2 - Gambling vs. Investing 2Document3 pagesEnglish Essay 2 - Gambling vs. Investing 2kort kubenNo ratings yet

- The Case AgainstDocument1 pageThe Case AgainstRodnei SilvaNo ratings yet

- Game Theory To Optimize Stock PortfolioDocument7 pagesGame Theory To Optimize Stock Portfolioashuking2020No ratings yet

- Estadistica y ApuestaDocument17 pagesEstadistica y ApuestaSergio PacoraNo ratings yet

- Asset Pricing and Sports BettingDocument76 pagesAsset Pricing and Sports BettingNeal Erickson100% (1)

- Are Markets Efficient - NoDocument3 pagesAre Markets Efficient - Noits4krishna3776No ratings yet

- Combinatorial Information Market Design: Robin HansonDocument13 pagesCombinatorial Information Market Design: Robin Hansonjagat4uNo ratings yet

- International Treasurer - October 2008 - The Financial Crisis Heats UpDocument16 pagesInternational Treasurer - October 2008 - The Financial Crisis Heats UpitreasurerNo ratings yet

- The Euro Sovereign Debt Crisis, Determinants of Default Probabilities and Implied Ratings in The Cds Market: An Econometric AnalysisDocument10 pagesThe Euro Sovereign Debt Crisis, Determinants of Default Probabilities and Implied Ratings in The Cds Market: An Econometric Analysisc_junk8912No ratings yet

- Capm and Beta in Impfect MarketDocument5 pagesCapm and Beta in Impfect Markettyma56tjNo ratings yet

- Setup Steps For OPM ModuleDocument3 pagesSetup Steps For OPM ModulekjganeshNo ratings yet

- Co-Operative Banking ProjecT2Document38 pagesCo-Operative Banking ProjecT2manindersingh9490% (1)

- Salt Lake City's Granary District and West Temple Gateway Redevelopment StrategyDocument13 pagesSalt Lake City's Granary District and West Temple Gateway Redevelopment StrategyThe Salt Lake TribuneNo ratings yet

- Small Country and Large CountryDocument3 pagesSmall Country and Large Countryhims08No ratings yet

- Module 4 Lesson 2Document8 pagesModule 4 Lesson 2Jan JanNo ratings yet

- Finanal Accounts - Solved ExamplesDocument11 pagesFinanal Accounts - Solved ExamplesDesmond Suting100% (2)

- Philippine Iron Construction & Marine Works, Inc.: Employment Application FormDocument4 pagesPhilippine Iron Construction & Marine Works, Inc.: Employment Application FormHarvey PagaranNo ratings yet

- Article Reveiw Done by Endeshaw YibeltalDocument4 pagesArticle Reveiw Done by Endeshaw Yibeltalendeshaw yibetal100% (2)

- FM Finals TestPaper PCO withANSDocument2 pagesFM Finals TestPaper PCO withANSmcle reyNo ratings yet

- Ictad SBD 01Document122 pagesIctad SBD 01Premasiri KarunarathnaNo ratings yet

- Account Closure Request Form: Account Holder's Details 1 2 0 8 9 4 0 0Document1 pageAccount Closure Request Form: Account Holder's Details 1 2 0 8 9 4 0 0sreenu naikNo ratings yet

- OK2022100500008350296D2OKash Loan ContractDocument1 pageOK2022100500008350296D2OKash Loan ContractAbejoye AdebusuyiNo ratings yet

- The Internal Environment SWOT AnalysisDocument3 pagesThe Internal Environment SWOT AnalysisMirta SaparinNo ratings yet

- Housing Policy in India PDFDocument26 pagesHousing Policy in India PDFabhishek yadavNo ratings yet

- Morgan Stanley CLDocument1 pageMorgan Stanley CLSher Bazeed KhanNo ratings yet

- Electronic JournalDocument22 pagesElectronic JournalEdmund Pulvera Valenzuela IINo ratings yet

- Befa Mid-Ii B.tech Iii YearDocument5 pagesBefa Mid-Ii B.tech Iii YearNaresh GuduruNo ratings yet

- BW Object Equivalent To A BPC CubeDocument31 pagesBW Object Equivalent To A BPC Cubesshah2112No ratings yet

- MTP 14 28 Answers 1701406110Document11 pagesMTP 14 28 Answers 1701406110aim.cristiano1210No ratings yet

- M7 - P2 Corporate Income Taxation (15B) - Students'Document46 pagesM7 - P2 Corporate Income Taxation (15B) - Students'micaella pasionNo ratings yet

- Written Assignment Unit2Document5 pagesWritten Assignment Unit2modar KhNo ratings yet

- Newton CaseDocument1 pageNewton CaseSaran SeeranganNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument2 pagesDocumentNadella HemanthNo ratings yet

- Sonal Project (Transfer of Property Act)Document15 pagesSonal Project (Transfer of Property Act)Handcrafting BeautiesNo ratings yet

- MCQ - NflatDocument5 pagesMCQ - Nflatvihaan.kharbandaNo ratings yet

- US Internal Revenue Service: F8453ol - 2003Document2 pagesUS Internal Revenue Service: F8453ol - 2003IRSNo ratings yet