Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Knowledge Ment Perf Index

Knowledge Ment Perf Index

Uploaded by

Pari SavlaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Knowledge Ment Perf Index

Knowledge Ment Perf Index

Uploaded by

Pari SavlaCopyright:

Available Formats

Expert Systems with Applications

Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745 www.elsevier.com/locate/eswa

Knowledge management system performance measure index

Shu-Mei Tseng

*

Department of Information Management, I-Shou University, 1, Section 1, Hsueh-Cheng Road, Kaohsiung 840, Taiwan, ROC

Abstract For years, the evaluation of knowledge management (KM) performance has become increasingly important since it directly provides the reference for directing the strategic organization learning and, by which the capabilities are generated to match the requirement to enhance enterprise competitiveness. It implies that company has strived to manage knowledge more eectively and eciently to improve its performance. Nevertheless, it is not yet fully understands how enterprise can successfully implement KM. In addition, despite the growing body of theory, there are relatively few KM studies which make an explicit connection between knowledge management system (KMS) and KMS itself performance. By partitioned the activities of KMS into three processes: KM strategic, the plan of KM, and implementation of KM plan, the study explores the KMS performance indicators which are useful to assess the KMS performance for rms. 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Knowledge management strategic; Plan; Implementation; Performance

1. Introduction Recent years, many scholars have attempted to measure the contribution of the KM by dierent methods (Malhotra & Segars, 2001; Maltz, Shenhar, & Reilly, 2003; Ngai & Chan, 2005). Because knowledge is rapidly becoming a critical asset for promoting the companys future performance, it is therefore vital that indictors and measure are developed in order to allow top management to make decision regarding KM activities (Carrillo & Gaimon, 2004; Pfeer & Sutton, 1999; Ribiere & Sitar, 2003). Furthermore, how to leverage knowledge in management activities and what advantage the KM can provide for the corporation is still unclear (Choi & Lee, 2003; Ford & Chan, 2003). Thus, managers usually confront with the diculty of the decisions of what and how to implement KM for attaining the required performance in a turbulent world and are in double about KM roles of being in the rms management

Tel.: +886 7 6577711x6552; fax: +886 7 6577056. E-mail address: shumei.tseng59@msa.hinet.net

infrastructure (Ruiz-Mercader, Meron o-Cerdan, & Saba nchez, 2006). ter-Sa Several studies have proposed the concept of KM performance to describe the performance improve between the enterprises current capability and the capabilities improve by KM. Choi and Lee (2002, 2003) have been veried that human strategy is more likely to be eective for socialization while system strategy is more likely to be eective for combination; and the dynamic style results in a higher performance than that the passive style while there is no dierence of performance between human and system oriented styles. Kalling (2003) suggests that the concept of KM is divided into three instances; development, utilization and capitalization, based on the assumption that knowledge is not always utilized, and that utilized knowledge does not always result in improved performance. Yim, Kim, Kim, and Kwahkc (2004) develop a method of knowledge-based decision making (KBDM) to understand which decision factor has a higher impact on performance, and to discern decision alternatives. Carrillo and Gaimon (2004) dened three repositories of knowledge that drive performance for the manufacturing plant level: technical systems, workforce knowledge, and the managerial systems.

0957-4174/$ - see front matter 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2006.10.008

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745

735

They found that dierent characterizations of the managerial systems have a profound eect on managerial behavior and plant performance. Lee, Lee, and Kang (2005) provides a new metric, knowledge management performance index (KMPI), for assessing the performance of a rm in its KM. They dened ve components that can be used to determine the knowledge circulation process (KCP). When KCP eciency increases, KMPI will also expand, enabling rms to become knowledge-intensive. Lin and Tseng (2005a) categorize the ve management gaps in implementation of KM activities and illustrate the links between KM activities and corporate performance. The results reveal that corporate performance is signicantly inuenced by these management gaps. For years, companies have strived to manage knowledge more eectively, the primary motivation being improved corporate performance (Choi & Lee, 2003). Germain, Dro ge, and Christensen (2001) stated performance control can be of two types: formulate performance-related issues such as costs, product quality, and prot levels; and compare its cost, quality, customer satisfaction, and operations to the benchmark of the industry or leaders. Furthermore, Teece (2000) argues superior performance depends on the ability of rms to innovate, to protect knowledge assets and to use these knowledge assets. Fliaster (2004) claimed the strong orientation of the executive culture towards short-term nancial performance measures and the ignorance of people issues is massively supported by the current remuneration systems. Therefore, performance measurement should be judged not only on nancial information (ROE or stock prices), as this is no longer sucient for understanding the dynamic environment. It is evident that non-nancial measures are becoming important to organization, which likes the level of trust perceived by the employees (Edvinsson, 1997; Robinson, Anumba, Carrillo, & Al-Ghassani, 2005; Robinson, Carrillo, Anumba, & AlGhassani, 2005). Despite the growing body of theory, there are relatively few KM texts that make an explicit connection between KM activities and KM itself performance (Kalling, 2003; Lee et al., 2005). In other word, much KM research has focused on identifying, storing, and disseminating process related knowledge in an organized manner, little empirical work has been undertaken (Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Yim et al., 2004). Furthermore, although the unexpected number of failures of KM, there are some evidences of its positive inuence on organisational performance (Choi and Lee, 2002; Carrillo & Gaimon, 2004; Choi & Lee, 2003; Kalling, 2003; Lee et al., 2005; Lin & Tseng, 2005a). So, it can be expected that successful KM initiatives could transform the business into a sustainable higher performance. Thus, it is valuable to investigate how managers can implement KMS eectively in order to enhance KMS itself performance. Our research objective was therefore to explore the relationship between KMS and KMS itself performance. And, we combined both nancial and nonnancial measures methods, proposed a more useful and

rigorous method to assess KMS itself performance with the ability to illustrate and suggest future business actions that the rms should take to improve KMS itself performance. 2. Conceptual framework A conceptual framework of KMS, referenced to the KM gaps (Lin & Tseng, 2005b), is used as the basis of this study. It has four components, which are depicted in Fig. 1. The rst component of KMS is KM strategic. Many rms cannot identify knowledge of where to go in their organization to obtain the relevant information and resources that are required to develop an appropriate strategic direction (Kim, Yu, & Lee, 2003). Therefore, the role for top managers in implementing KM is to review the internal and external environments of the enterprise in order to understand its strength, weakness, opportunities, and threats in conducting KM activities (Ndlela & Toit, 2001; Wakeeld, 2005). External analysis is crucial from the strategy aspect of KM, because it ensures that the enterprise can appropriately implement the KM program to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage (Krogh, Nonaka, & Aben, 2001; Moorman, 1995). In this process, the weaknesses in competitors must be exploited and their strengths must be bypassed or neutralized. Also, depending on the outcome of the analysis of the enterprises current position and capability with regard to the aspect of KM, the enterprise can address opportunities and threats to formulate a suitable KM strategy (Dess, Lumpkin, & Covin, 1997; Hendriks & Vriens, 1999; Teece, 2000). The plan of KM is the second component. Under the realization of the positions for the enterprises internal and external environments, top management are able to enact a proper plan to guide the enterprise in implementing

KMS deployment

KM strategic

The plan of KM

Implementation of KM plan

KM performance Financial measure Non-financial measure

Fig. 1. Conceptual model.

736

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745

KM (Robinson, Carrillo, et al., 2005; Rubenstein-Montano et al., 2001). Eective KM, based on knowledge, should be able to support the core tasks of business management, namely that of decision making and strategic planning (Yim et al., 2004). Although there are many ways in which KM can be practiced, but what method may be more suitable depending on the specic organization such as business object, nature of products and services, organizational culture, company size, availability of resources, etc. which will act as moderating factors which aect that how KM should be implemented (Wong & Aspinwall, 2006). Thus, in establishing the KM plan, it is crucial to diagnose and understand its value, and how suitable the plan to build the KMS for the enterprise. The action plan should include schedule, people involved and resources required (Goold, 2005). Furthermore, KM plans should also include of the design of the businesss workow and its functions (Chow, Choy, Lee, & Chan, 2005). Implementation of KM plan is the third component of KMS. Employees are often afraid that their personal value might be negatively aected after sharing their knowledge, especially, so they unwilling to share their own knowledge. And, there was a tendency to keep knowledge in their personal computers, rather than to share and disseminate it to other employees (Wong & Aspinwall, 2006). Hence, the main stimulus for the company to implement KM was to improve this situation. Therefore, when implementing KM, the top management must keep in mind that change is usually not accepted by employees, and it will take time before these changes become eective (Lin & Tseng, 2005b; Shaw & Edwards, 2005). Furthermore, eective implementation of KM strategy includes a clear denition of what knowledge needs to be achieved and what motivations must be created (Campbell & Luchs, 1997). If dierent opinions exist within the organization about the denition of core knowledge, the value of knowledge, and the introduction procedures of the KMS, the enterprise will certainly be confronted with many obstacles when implementing KM. KM performance measures is deeply concerned on fourth component, in which several argumentations involved in why nancial measure and non-nancial measure should be included in KM measurement system (Maltz et al., 2003). It reveals that rm confront with diculty in determining which specic measures are critical to their rm. Chakravarthy (1986) found that classic nancial measures (ROE, ROC, ROS) are incapable of distinguishing dierences in performance between these rms. Kaplan and Norton (1996) also asserted that traditional nancial accounting measures (e.g., ROI, EPS) can give misleading signals for continuous improvement and innovation. It implies that the nancial measures which are based on traditional accounting practices with emphasis on short-term indicators such as prot, turnover, cash ow and share prices, are not a fully set to measure the organization performance, while non-nancial measures becoming important to organizations such as their customers, investors,

and stakeholders (Robinson, Anumba, et al., 2005). It is performance measures not only on nancial information, that non-nancial measures are becoming important to organization (Fliaster, 2004). Based on the discussion mentioned above, our researches will combination nancial measure and non-nancial measure to evaluate KMS performance. 3. Methods This study involves two-phased design and each is with distinct methodology. First, volumes of literature review and in-depth interviews with senior managers from four companies were used to collect data. Interviews are one of the most intensively used methods of data collection (Bryman & Burgess, 1999). The individual in-depth interviews that we will conduct are face-to-face and semi-structured nature, which is one of the most common approaches to interviewing in qualitative research (Bryman & Burgess, 1999). This type of interview involves the implementation of a number of predetermined questions or special topics. That allows the respondents to determine the direction and content of the interview within a broader framework provided by the interviewer. After each companys interviews were completed, the results were assembled, transcribed and e-mailed to the respondents for their review and approval eliminating any misinterpretation. It is expect to provide a richer and more holistic appreciation of the problems regarding KMS. Second, a questionnaire (developed through literature review and in-depth interviews) that quantied the constructs was mailed to the 500 largest corporations list in Taiwan compiled by the China Credit Information Service (2005). After three weeks, respondents were reminded by e-mail to submit the completed questionnaires. This measurement technique was used as a preliminary assessment of our understanding of the KMS and to verify whether the qualitative data from the interviews matched the quantitative responses. Final, we used the metric (Lee et al., 2005), knowledge management performance index (KMPI) to assess KMS performance. Furthermore, we adopted two specic measures: nancial and non-nancial factors to test and verify whether KMS performance index will results in higher KMS performance. The following sections will illustrate the main questions associated with the three KM deployment and the constructs of KMS performance. 3.1. KM strategic If KM is to be successfully directed, there must be an indisputable link between companys business strategic and its KM strategic (Tiwana, 2001). Managers need to capture what they learn both from the soft insights and experiences and from hard market data, and then synthesize that learning into a vision of the direction that business should pursue. Such strategic orientation requires knowledge of the external environment in which your company

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745

737

confronts and comprehension of the internal process that it undertakes. Therefore, to measure KM strategic, two constructs were needs: external analysis and internal analysis. The rst was measured by assessing the responses to four questions and internal analysis was measured by answers to three items, which are depicted in Table 1. 3.2. The plan of KM First of the core tasks of management is to dene goals so as to give direction to the companys basic process. The processes involved in dening goals are the starting point of KM (Probst, Raub, & Romhardt, 2000). The ultimate goal of KM is to create value through knowledge usage. A strong emphasis on KM in the rms business plan indicates the importance of well-developed strategies to let employees perceive the managers strategic visions and their leadership style for establishing a program to achieve the rms overall objective (John, Chimay, & Patricia, 2002). Second of the core tasks of management is to identify employee orientation. KM problems often occur because employees are not well suited for their positions. Managers commonly do not give enough attention or

Table 1 KM strategy items Constructs External analysis Items

devote sucient resources to hiring and selection processes (Robinson, Carrillo, et al., 2005; Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1988). They usually do not know what the employees, especially the experts, are thinking about the market developments and technological trends (Fliaster, 2004). Thirdly, many of the technologies that support the management of knowledge have been around for long time. To analyze these extant technologies, we can make judgments about what can be take as is, and what more needs to be added to leverage existing infrastructure (Desouza, 2003; Quintas, Lefrere, & Jones, 1997; Spender, 1996; Tiwana, 2001). Thus, the degree of KM plan depends on constructs such as goal setting, employee orientation, and KMS infrastructure. Goal setting was measured by two items; employee orientation was operationalized by three items, and KMS infrastructure was measured by ve items, which are depicted in Table 2. 3.3. The implementation of KM plan It is well known that the top management support and senior levels understanding is crucial to a successful KM implementation (Fliaster, 2004). Unless all employees

Remark Ndlela and Toit (2001) Holsapple and Joshi (2002) Maltz et al. (2003) Gray and Meister (2006) Ndlela and Toit (2001) Kim et al. (2003) and Woo et al. (2004)

Q1. Does the core knowledge own by rm dominated in the industry? Q2. Which industries have been developing knowledge that could pose a threat to you? Q3. Can employees screen out the useful KM for the rm from external environment? Q4. Can employees communicate the knowledge obtaining from external environment with their managers? Q1. Do you know about the knowledge that is critical to your rms success? Q2. What the infrastructure of information technology owning by rm can support the implementation of KM? Q3. Are barriers to implementing a KM program clearly understand by the rms upper management?

Internal analysis

Table 2 The plan of KM items Constructs Goal setting Items Q1. Do the goals of KM alignment with the rms goals? Q2. Are the goals of KM consistent with the individual goals? Employee orientation Q3. Do top managers and employees truly understand what KM to be? Q4. Do employees have the good skills to apply use the information technology for successful implementing the KM? Q5. Does rm commit to provide abundant resources to support KM? Q6. Can rms KMS exible support the formulation of KM strategic? Zeithaml et al. (1988) Fliaster (2004) Remark Probst et al. (2000), John et al. (2002) and Robinson, Carrillo, et al. (2005)

KMS infrastructure

Spender (1996), Quintas et al. (1997), Wiig et al. (1997), Hendriks and Vriens (1999), Tiwana (2001) and Desouza (2003)

Q7. Can the KMS provides multiple channels to satisfy the requirement for sharing of heterogeneous knowledge and preference? Q8. Can the employees satised with KMS when the size of knowledge communities has continuous growled? Q9. Does the rm provide friendly hardware to standardize the knowledge? Q10. Does the rm provide friendly software to standardize the knowledge?

738

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745

accept the whole notion of the KMS that company is building, they will have neither the inclination to use it nor support it. As a consequence, employees trust in senior leadership is one of the key drivers of employee commitment and willingness to share knowledge (Levin & Cross, 2004; Ribiere & Sitar, 2003). Furthermore, due to the tacit and dynamic nature of knowledge, it is dicult to measure knowledge assets with existing accounting systems (Claessen, 2005). Many companies fail to evaluate the results of KM to determine whether or not it meets expectations, therefore, a complete measurement system needs to be developed to evaluate whether the KM activities will enable the enterprise to enhance its competitiveness after implementation (Kreng & Tsai, 2003). Thus, an instrument to assess the degree of KM implementation used two constructs: employee commitment and measurement system. Based on relevant reference, we propose eight issues for the employee commitment and ve issues for measurement system, which are depicted in Table 3. 3.4. KM performance Lee et al. (2005) proposed a new metric, knowledge management performance index (KMPI) for assessing KM performance. They dened ve components to illustrate knowledge circulation process (KCP): knowledge creation, knowledge accumulation, knowledge sharing, knowledge utilization, and knowledge internalization. When KCP eciency increases, KMPI will also expand, enabling rms to become knowledge-intensive. The KMPI function was basically on a logistic function in which the contribution of KCP for years starts slowly but then

increases rapidly, slowing down at a mature level. Because the KCP is based on Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (2000) proposed knowledge conversion model (SECI): socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization, it is too intangible and abstract to evaluative KM activities. Therefore, it will be useful to develop a holistic framework to describe the fundamental steps of the implementation of the KMS. As a consequence, our research dened three components to illustrate the process of the KMS (Lin & Tseng, 2005b). A similar rational can be applied in the context of the processes of the KMS, which are KM strategic, the plan of KM, and implementation of KM plan, because the rate of KMS benets increase will be small while users unwillingness to share their own knowledge or their inability to understand exactly what KMS in the initial stage (Ford & Chan, 2003; Wong & Aspinwall, 2006). The rate then increases, as users become accept with it. The rate, however, slows as the benets approach the limit that can be gained from the system, or when competitors also implement the KMS. In this sense, we followed the logic of Lee et al. (2005) in developing knowledge management system performance index (KMSPI) KMSPIt 1 eKMSt 1 1

The KMS term in (Eq. (1)) is a function of the relative weight of the eigenvalue (RWE) of each component multiplied by the average factor value (AFV) of the corresponding KMS. KMS RWES AVES RWEP AVEP RWEI AVEI 2 where S is KM strategic, P is the plan of KM, and I is the implementation of KM plan.

Table 3 The implementation of KM plan items Constructs Employee commitment Items Q1. Do top managers support the knowledge communities? Q2. Do employees support the knowledge communities? Q3. Can knowledge communities mapped on to the existing organizational structure? Q4. Are top managers and employees both committed to implement KM? Q5. Do employees conceive that top mangers genuinely care about providing enough resources to them? Q6. Do employees feel they are cooperating rather than competing with each other in fullling the goals of KM? Q7. Do employees feel personally involved in the implementation and committee to devote themselves? Q8. Does the number of layers of the hierarchy of the organization structure is suitable for KM implementation? Q1. Does the rm realize what contribute of the assets and liabilities in knowledge balance sheet? Q2. Can the rm provide to build an appropriate knowledge repository? Q3. Have the rms to period update knowledge repository? Q4. Does the rm have an explicitly quantitative and nancial monitoring system and culture? Q5. Can which function or department of the rm be a successful prototype or benchmark? Remark Nonaka (1991, 1994) Ribiere and Sitar (2003) Cummings (2004) and Ditillo (2004) Fliaster (2004) and Ruiz-Mercader et al. (2006)

Measurement system

Probst et al. (2000) Kreng and Tsai (2003) and Chang, Choi and Lee (2004) Ford and Chan (2003)

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745

739

3.5. Test of KMS performance index Because there are many results reveal that corporate performance is signicantly inuenced by the KM activities (Pfeer & Sutton, 1999; Ribiere & Sitar, 2003). Therefore, we hypothesize that rms with good KM strategic, plan, and implementation will obtain high degree of their KMS performance index, and that those with a greater KMS performance index will results in higher KM performance. In order to test and verify this idea, we adopted two specic measures: nancial and non-nancial factors. The nancial one is measured by the average change in sale of the recent three years (20022004) (Lee et al., 2005). The non-nancial is measured by competitiveness and innovativeness (Lin, Yeh, & Tseng, 2005). Thus, our research hypotheses were: Hypothesis 1. If KMS performance index is greater, then the average change in nancial measure is signicantly better. Hypothesis 2. If KMS performance index is greater, then the non-nancial measure is signicantly better. 4. Samples and measures Taiwan has long been an active player in the world economy and an important trader in the global market (Wang, 2003). Taiwan is an exporting as well as an importing nation. Around 80% of the machines, tools and accessories it produces are purchased by other countries (Koepfer, 2001). Moreover, Taiwan is the worlds biggest manufacturer for dozens of computer-related products such as notebook computers, palm scanners, motherboards, and modems. In terms of production value, it ranks third in the world in computer manufacturing and fourth in semiconductors (Ministry of Economic Aairs, Republic of China homepage, MOEA, 2005). Taiwan is also home to one of Asias most open and well-developed Internet communities (Trappey & Trappey, 2000). All of the evidence above points to Taiwans industry as being a suitable sample for exploring the issues concerned with KM performance. Therefore, the model empirically investigates Taiwan rms to nd the method to accessing KMS performance of a rm. The draft questionnaire was examined by interviewing four companies for content and validity, and minor modications of the wordings of some survey items were made. The initial sample consisted of 500 divisions of rms noted in the largest corporations in Taiwan China Credit Information Service Top 5000 (2005). The senior managers or the directors of KM department were used as informants because they tend to play key roles in organizational activities (James, Stoner, Freeman, Daniel, & Gilbert, 1995). Informants were mailed a questionnaire and a cover letter that explained the purpose of this study and promised a summary of the results if they completed questionnaire and were interested in this study result. Three weeks following the rst mailing, non-respondents

were telephoned, reminded of the questionnaire, and encouraged to complete and return it. Research constructs were operationalized through related studies and a pilot test. Multi-item scales were used for measuring the research variables using a seven-point Likert-type scale. 5. Sample analysis 5.1. Sample characteristics There were 65 responses, of which 57 were complete and usable for analysis, yield an eective response rate of 11.4%. In this study the response rate of the questionnaire is lower that may be they were too busy to full out this questionnaire. In addition, we think that may be they do not understood about the topic in this respect of KM or they have not pursued KM yet, so they unable to answer this questionnaire (Lin & Tseng, 2005a). To verify this argumentation, we call to the respondent rm to check it owns the independent unit of KM. It shows that there is only 79 rms own the independent unit of KM and the unit is usually directed by the department of information management, research and development as well as human resource management. This implies that the 65 respondent seems to be reasonable in the study. Table 4 shows the demographics of the sample. Careful non-response analyses were applied to ensure the absence of non-response biases. Comparing the responding and non-responding rms in terms of total assets and annual sales, no signicant dierences were found based on independent sample t-test (p > 0.05). Thus, there appeared to be no nonresponse bias. The test results are provided in Table 5. 5.2. Test results Factor analysis is a mathematical tool which can be used to examine a wide range of data sets. It is applied as a data

Table 4 Demographic characteristics of the responding rms (n = 57) Percentage of rms Industry Manufacturing companies Non-manufacturing companies Government enterprises Banking & nancing Annual sales Less than $3 billion 3 billion to below 15 billion 15 billion to below 50 billion 50 billion to below 100 billion 100 billion and above Number of employees <1000 10002000 20013000 >3000 37.0 25.9 10.2 26.9 7.4 40.7 26.9 5.6 19.4 11.8 39.7 22.1 26.4

740

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745 Table 7 Relative weight of eigenvalue (RWE) P-value* 0.12 0.09 Factor KM strategic Plan of KM Implementation of KM Total Eigenvalue 4.994 7.072 9.425 21.491 RWE 0.23 0.33 0.44 1

Table 5 Homogeneity test between responding and non-responding Characteristics Total assets Annual sales

*

Test Independent sample t-test Independent sample t-test

Statistical t-value 1.57 1.71

P > 0.05 indicates no non-response bias.

reduction or structure detection method. In this way, factor analysis validated the measures used in the KMS performance index calculation model. Exploratory factor analysis was adopted using the orthogonal rotation method. Five factors had Cronbachs alpha value greater than 0.7, indicating that internal consistency is guaranteed for the measurement instruments. Table 6 shows the factor structure of variables, where reliability and convergent validity were signicant because Cronbachs alpha was greater than or equal to 0.70, and all convergent validity was greater than 0.60 (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Tables 7 and 8 summarize RWE and AFV, all of which were required to calculate KMS performance index as shown in Table 9. Table 10 shows the correlation between KMS performance index and the two measures. Hypotheses 1 was proved at the 0.1 signicance level, while Hypotheses

2 was proved at the 0.05 signicance level. This show that the value of KMSPI by indicating the signicance of correlation between KMSPI and the two measures. The empirical results, i.e. Tables 610 show that, as conceptual framework, the three components of KMS signicantly impact KMS performance. The eectiveness and eciency KMS was executed will increase the KMS performance. 6. Discussion Based on the results of statistical analysis and discussion mentioned above, we conclude that the quality of KM regarding to three components of KMS will aect KMS performance. It is imperative that the more eective and eciency that the three components can achieve, the better the performance that KMS attains. Therefore, the detailed discussions of the three components of the KMS are stated as the follows. 6.1. KM strategy Kim et al. (2003) dene knowledge strategy planning as a process of creating an organizational knowledge vision, designing KM architectures, and organizing a set of activities and resources to implement them. Because each enterprise has its own unique knowledge domain, as well as certain specic problems that can be solved, the critical task of top managers is to identify the core knowledge which is necessary to achieve and maintain competitive advantages (Ndlela & Toit, 2001). The business improvement strategy is more advanced than the KM strategy but it is recognized that there is a need for better alignment or integration of KM into business improvement (Long & Seemann, 2000; Maier & Remus, 2001). In other words, to leverage the capability of the knowledge for the organization, top management should ensure the consistency between the enterprise mission and knowledge strategy by clearly dening knowledge goals that are connected with functional strategies (Kim et al., 2003). It is supportive for providing a conceptual framework to formulate the KM strategy as showed in Fig. 2, which consists of external environmental scan and internal scrutiny by Porters ve forces model and knowledge value chain (Holsapple & Singh, 2001), respectively; and initially to result in so called SWOT. In the external environment analysis, a current situation and characteristics of the industry were examined with a focus on the market. In

Table 6 Factor structure of variables (N = 57) Factor KM strategic by external analysis KM strategic by internal analysis Plan of KM Eigenvalue Cronbachs Items Factor Convergent alpha loadings validity 2.843 0.8642 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 0.737 0.739 0.899 0.838 0.860 0.648 0.836 0.793 0.841 0.779 0.856 0.830 0.828 0.904 0.849 0.872 0.851 0.871 0.825 0.821 0.747 0.728 0.708 0.648 0.630 0.707 0.813 0.848 0.841 0.631 0.6626 0.6736 0.7813 0.7540 0.6750 0.5446 0.5972 0.7439 0.8026 0.7294 0.8177 0.7866 0.7832 0.8765 0.8101 0.8358 0.8124 0.8057 0.8214 0.7707 0.8012 0.8514 0.8140 0.7687 0.6430 0.6373 0.8549 0.8025 0.8417 0.7427

2.151

0.7642

7.072

0.9537

Implementation 5.270 of KM by employees committee

0.9384

Implementation 4.155 of KM by measurement system

0.9093

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745 Table 8 Average factor value Company Com1 Com2 Com3 Com4 Com5 Com6 Com7 Com8 Com9 Com10 Com11 Com12 Com13 Com14 Com15 Com16 Com17 Com18 Com19 Com20 Com21 Com22 Com23 Com24 Com25 Com26 Com27 Com28 Com29 Com30 Strategy 0.6633 0.7636 0.3497 0.6053 1.538 0.8879 0.6769 0.530 0.5056 0.0123 0.5604 0.5161 0.9645 0.2338 0.539 0.5049 0.5588 0.712 0.623 0.087 1.1039 0.672 0.100 0.3358 1.2096 0.5056 0.5056 1.145 0.108 1.504 Plan 1.0456 0.6413 0.6351 0.8408 2.619 0.9441 0.5655 0.839 0.335 0.9583 0.6322 1.0601 1.1465 0.337 0.1494 0.4519 1.3534 1.537 0.029 0.0578 1.8448 1.134 1.243 0.057 2.0453 0.6523 0.9448 0.935 0.2586 1.033 Implement 1.0395 0.5454 0.5477 0.5712 1.588 0.7641 0.7830 0.343 0.458 0.6345 0.3514 0.7623 1.1074 0.328 0.125 0.5065 0.5843 1.299 0.577 0.2345 1.2884 0.452 0.220 0.175 1.3362 0.8436 1.0346 0.565 0.155 0.521 Company Com31 Com32 Com33 Com34 Com35 Com36 Com37 Com38 Com39 Com40 Com41 Com42 Com43 Com44 Com45 Com46 Com47 Com48 Com49 Com50 Com51 Com52 Com53 Com54 Com55 Com56 Com57 Strategy 0.0416 0.093 0.523 0.7957 0.5477 0.364 0.4554 0.9300 0.0070 0.2201 0.4501 0.302 0.364 0.010 0.006 0.8611 0.683 1.679 0.913 0.4506 0.988 0.7006 0.549 0.193 0.815 0.854 1.018 Plan 0.248 0.5484 1.043 1.0517 0.7500 0.441 1.0517 2.0453 0.557 0.944 0.1550 1.037 1.238 0.142 0.3564 0.1585 0.539 2.511 0.1543 0.735 0.144 0.4522 0.532 0.538 0.428 0.628 1.138

741

Implement 0.214 0.3020 0.067 0.7937 0.214 0.2088 0.5368 1.3362 0.636 0.176 0.2397 0.847 0.706 0.2217 0.037 0.3943 0.690 1.283 0.190 0.624 0.446 0.0246 0.585 0.571 0.959 0.822 1.102

Table 9 KMSPI calculation Company Com25 Com38 Com21 Com13 Com1 Com27 Com34 Com6 Com17 Com12 Com26 Com37 Com7 Com4 Com2 Com10 Com3 Com11 Com16 Com46 KMSPI 0.823624 0.814090 0.806838 0.747910 0.722125 0.707516 0.706695 0.700997 0.696838 0.690829 0.668807 0.665538 0.665270 0.661069 0.651874 0.645267 0.629731 0.620623 0.619676 0.604419 Company Com52 Com32 Com35 Com41 Com20 Com45 Com44 Com29 Com24 Com15 Com36 Com31 Com9 Com14 Com49 Com40 Com19 Com50 Com39 Com51 KMSPI 0.579624 0.572589 0.569282 0.564685 0.525495 0.524912 0.512064 0.497920 0.495217 0.467520 0.465654 0.458317 0.451127 0.449704 0.439533 0.416147 0.399543 0.397947 0.386451 0.384231 Company Com54 Com33 Com23 Com8 Com53 Com47 Com22 Com55 Com56 Com42 Com43 Com28 Com30 Com57 Com18 Com48 Com5 KMSPI 0.383753 0.378922 0.370408 0.365846 0.363549 0.345397 0.325604 0.320565 0.317356 0.313347 0.309269 0.305622 0.285644 0.250664 0.223887 0.144308 0.128197

Table 10 Correlation between KMS performance index and nancial and nonnancial measures Measures item Financial Non-nancial

* **

Correlation with KMSPI 0.295* 0.608**

P < 0.1. P < 0.05.

Maltz et al., 2003). The internal environment analysis identied a need for securing and protecting its core knowledge. In our study, we found whether rms know about the knowledge that is critical to their success and top management clearly understand the barriers to implementing a KM program are very important (Kim et al., 2003; Woo, Clayton, Johnson, Flores, & Ellis, 2004). Through the process of carrying out KM strategy, an organization becomes aware of its weakness, strength, opportunities, and threats of KM for achieving its goal (Akhter, 2003; Dess et al., 1997; Krogh et al., 2001). Finally, according to the characteristic of available capacity, the rm could derive the appropriate measure to evaluate the current KM strategic performance. 6.2. The action plan of KM After exploring rms external and internal environments, they can understand the current position of an

our study, we found whether employees can screen out the useful KM for the rm from external environment and employees can communicate the knowledge obtaining from external environment with their managers are very important (Gray & Meister, 2006; Holsapple & Joshi, 2002;

742

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745

Central Focus of Corporate KM Strategy

The Knowledge Five Force Model The Knowledge Chain Model Leadership Coordination Control Measurement

Acquisition Selection Generation Internalizatior Externalization

Risk of entry by new potential knowledge

Learning Projection

Power of Supplier's Knowledge

Rivalry among Established Knowledge

Power of Customer's Knowledge C

Threat of Substitutes Knowledge

Corporate Internal Scrutiny Knowledge Value Chain Analysis Definition of Strengths and Weaknesses

Corporate External Analysis Knowledge Five Forces Analysis Identification of Opportunities and Threats

KM Strategy posture of the Firm

Fig. 2. KM strategy.

organization and recognize where it should go in the future. Knowledge related to business processes or individual tasks are identied through decomposing business processes. In other woods, strategies of KM should be delineated in an organizational context. In this phase, KM goal and strategies are set up based on the outputs of previous phases (Green & Ryan, 2005). In other woods, the goals of KM must be alignment with the rms goals. Companies should aim to ensure the use and development of skills and knowledge that are relevant to the organizations objectives (John et al., 2002; Probst et al., 2000; Robinson, Carrillo, et al., 2005). In addition, KM problems often occur because employees are not well suited for their positions and managers commonly do not give enough attention or devote sucient resources to hiring and selection processes. Therefore, rms must train employee to have good skill to apply use the information technology for implementing the KM and provide abundant resource to support KM (Fliaster, 2004; Zeithaml et al., 1988). If there is an absence of total management commitment, then KM cannot be implemented successful. Furthermore, due to the rapidly of growing knowledge, the KMS should provide multiple channels to satisfy the requirement for sharing of heterogeneous knowledge and preference (Desouza, 2003; Quintas et al., 1997). In conclusion, the action plan or introduce KM map should be formulate and state clearly, in which the connecting between KM strategic, rm

objectives and KM map are declared to provide a fundamental base for carefully selecting the implementing team and platform appropriately with a initial diagnosis and KM audit to provide the infrastructure and development direction of the KM (Gravill, Compeau, & Marcolin, 2006). 6.3. Implementation of KM Eective implementation of KM strategies includes a clear denition of what knowledge needs to be achieved and what motivations must be created (Campbell & Luchs, 1997). The dierent opinions may exist within the organization about the denition of core knowledge, the value of knowledge, and the introduction procedures of the KMS, the enterprise should rstly carefully tackle the problems in implementing the KM. More clearly, employees perceptions of what type of knowledge they will be appreciated for rms support them to own or learn the knowledge may be dierent depended on their positions and roles (Nonaka, 1991). Therefore, to match the perceptions of all employees in dierent positions, the goals and the plan that should be committed by all levels of employees which have been became critical issues in implementation KMS. That is top managers and employees should fully support knowledge communities, while knowledge communities must map to the existing organizational structure (Cum-

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745

743

KM strategy Internal analysis External analysis

The plan of knowledge management

Goal setting Employee orientation KMS Infrastructure

Implementation of knowledge management

Employee commitment Measurement system

Fig. 3. The critical factors of KMS.

mings, 2004; Ditillo, 2004; Ribiere & Sitar, 2003; RuizMercader et al., 2006). In addition, we found the rm must to period update knowledge repository to sure the knowledge base quality and the complete measurement system needs to be developed in order to evaluate whether the company will enable the enterprise to enhance their competitiveness after the implementation of KMS (Ford & Chan, 2003; Kreng & Tsai, 2003; Chang et al., 2004). Therefore, the result of study implicates that the success to implement the KMS should be rstly to obtain all employees committed and then appropriate measure system to evaluate the KM performance. 7. Conclusion Proper management and leveraging of knowledge can propel an organization to become more adaptive, innovative and intelligent. Thus, KM has become an important strategy for improving corporate competitiveness and performance (Wong & Aspinwall, 2004, 2006). However, the links between performance and the knowledge aspects of the models are often ignored or not properly exploited (Robinson, Carrillo, et al., 2005). Performance management should be underpinned by a learning culture and KM strategic to enhance an organizations ability to continuously improve its business performance (Garvin, 1993; Lee & Kim, 2001; Nevis, DiBella, & Gould, 1995). Therefore, the purpose of this research was to provide a management-oriented conceptual framework to describe the inuence KMS performance in implementing the KMS. Meanwhile, we proposed a new metric for assessing KMS performance. As the eciency of the three components of KMS increases, KMS performance is enhanced based on a review of the literature and statistical analysis. The power of KMS performance index to represent the nancial and non-nancial performance of rms was

tested. We founded when KMS performance index increases, KMS performance likewise improves. That mean the quality of KMS will aect KMS performance. Therefore, we address the critical factors about how to improve the quality of KMS as Fig. 3. KMS designers can used the processes of the KMS to leading the KMS performance. References

Akhter, S. H. (2003). Strategic planning, hypercompetition, and knowledge management. Business Horizons, 1924. Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundation and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107136. Bryman, A., & Burgess, R. G. (1999). Qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication. Campbell, A., & Luchs, K. S. (1997). Core competency-based strategy. London: International Thomson Business Press. Carrillo, J. E., & Gaimon, C. (2004). Managing knowledge-based resource capabilities under uncertainty. Management Science, 50(11), 15041518. Chakravarthy, B. S. (1986). Measuring strategic performance. Strategic Management Journal, 7(5), 437458. Chang, J., Choi, B., & Lee, H. (2004). An organizational memory for facilitating knowledge: an application to e-business architecture. Expert Systems with Applications, 26(2), 203215. Choi, B., & Lee, H. (2002). Knowledge management strategy and its link to knowledge creation process. Expert Systems with Applications, 23(3), 173187. Choi, B., & Lee, H. (2003). An empirical investigation of KM styles and their eect on corporate performance. Information & Management, 40(5), 403417. Chow, H. K. H., Choy, K. L., Lee, W. B., & Chan, F. T. S. (2005). Design of a knowledge-based logistics strategy system. Expert Systems with Applications, 29(2), 272290. Claessen, E. (2005). Strategic use of IC reporting in small and mediumsized IT companies: a progress report from a Nordic project. Journal of Intellectual Capita, 6(4), 558569. Cummings, J. N. (2004). Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Management Science, 50(3), 352364.

744

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745 Lee, K. C., Lee, S., & Kang, I. W. (2005). KMPI: measuring knowledge management performance. Information & Management, 42(3), 469482. Levin, D. Z., & Cross, R. (2004). The strength of weak ties you can trust: the mediating role of trust in eective knowledge transfer. Management Science, 50(11), 14771490. Lin, C., & Tseng, S. M. (2005a). Bridging the Implementation gaps in the knowledge management system for enhancing corporate performance. Expert System with Applications, 29(1), 163173. Lin, C. H., & Tseng, S. M. (2005b). The implementation gaps for the knowledge management system. Industrial Management & Data System, 105(2), 208222. Lin, C. H., Yeh, J. M., & Tseng, S. M. (2005). Case study on knowledge management gaps. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(3), 3650. Long, D. D., & Seemann, P. (2000). Confronting conceptual confusion and conict in knowledge management. Organizational Dynamics, 29(1), 3344. Maier, R., & Remus, U. (2001). Toward a framework for knowledge management strategies: process orientation as strategic starting point. In Proceedings of the 34th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, US. Malhotra, G. A., & Segars, A. (2001). Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185214. Maltz, A. C., Shenhar, A. J., & Reilly, R. R. (2003). Beyond the balanced scorecard: rening the search for organizational success measures. Long Range Planning, 36(2), 187204. Ministry of Economic Aairs, National Information and Communications Infrastructure. <www.moeaidb.gov.tw> Accessed 23.05.05. Moorman, C. (1995). Organizational market information processes: cultural antecedents and new product outcomes. Journal of Marketing Research, 32(3), 318335. Ndlela, L. T., & Toit, A. S. A. (2001). Establishing a knowledge management programme for competitive advantage in an enterprise. International Journal of Information Management, 21(2), 151165. Nevis, E. C., DiBella, A. J., & Gould, J. M. (1995). Understanding organizations as learning systems. Sloan Management Review, 36(2), 7385. Ngai, E. W. T., & Chan, E. W. C. (2005). Evaluation of knowledge management tools using AHP. Expert Systems with Applications, 29(4), 889899. Nonaka, I. (1991). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, 69, 96104. Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 1437. Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., & Konno, N. (2000). SECI, Ba and Leadership: a unied model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 534. Pfeer, J., & Sutton, R. (1999). The knowingdoing gap. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Probst, G., Raub, S., & Romhardt, K. (2000). Managing knowledge building blocks for success. John Wiley & Sons, LTD. Quintas, P., Lefrere, P., & Jones, G. (1997). Knowledge management: a strategic agenda. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 385391. Ribiere, V. M., & Sitar, A. S. (2003). Critical role of leadership in nurturing a knowledge-supporting culture. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1(1), 3948. Robinson, H. S., Anumba, C. J., Carrillo, P. M., & Al-Ghassani, A. M. (2005). Business performance measurement practices in construction engineering organizations. Measuring Business Excellence, 9(1), 1322. Robinson, H. S., Carrillo, P. M., Anumba, C. J., & Al-Ghassani, A. M. (2005). Review and implementation of performance management models in construction engineering organizations. Construction Innovation, 5(4), 203217. Rubenstein-Montano, B., Liebowitz, J., Buchwalter, J., McCaw, D., Newman, B., & Rebeck, K.The Knowledge Management Methodology Team. (2001). A systems thinking framework for knowledge management. Decision Support Systems, 31(1), 516.

Desouza, K. C. (2003). Strategic contributions of game rooms to knowledge management: some preliminary insights. Information & Management, 41(1), 6374. Dess, G. G., Lumpkin, G. T., & Covin, J. G. (1997). Entrepreneurial strategy making and rm performance: tests of contingency and congurational models. Strategic Management Journal, 18(9), 677695. Ditillo, A. (2004). Dealing with uncertainty in knowledge-intensive rms: the role of management control systems as knowledge integration mechanisms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(34), 401 421. Edvinsson, L. (1997). Developing intellectual capital at Skandia. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 366373. Fliaster, A. (2004). Cross-hierarchical interconnectivity: forms, mechanisms and transformation of leadership culture. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 2(1), 4857. Ford, D. P., & Chan, Y. E. (2003). Knowledge sharing in a multi-cultural setting: a case study. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1(1), 1127. Garvin, D. A. (1993). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 7891. Germain, R., Dro ge, C., & Christensen, W. (2001). The mediating role of operations knowledge in the relationship of context with performance. Journal of Operations Management, 19(4), 453469. Goold, M. (2005). Making peer groups eective: lessons from BPs experiences. Long Range Planning, 38(5), 429443. Gravill, J. I., Compeau, D. R., & Marcolin, B. L. (2006). Experience eects on the accuracy of self-assessed user competence. Information & Management, 43(3), 378394. Gray, P. H., & Meister, D. B. (2006). Knowledge sourcing methods. Information & Management, 43(2), 142156. Green, A., & Ryan, J. J. C. H. (2005). A framework of intangible valuation areas (FIVA): aligning business strategy and intangible assets. Journal of Intellectual Capita, 6(1), 4352. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall International Inc. Hendriks, P. H. J., & Vriens, D. J. (1999). Research knowledge-based systems and knowledge management: friends or foes?. Information & Management 35(2), 113125. Holsapple, C. W., & Joshi, K. D. (2002). Knowledge manipulation activities: results of a Delphi study. Information & Management, 39(6), 477490. Holsapple, C. W., & Singh, M. (2001). The knowledge chain model: activities for competitiveness. Expert Systems with Applications, 20(1), 7798. James, A. F., Stoner, R., Freeman, E., Daniel, R., & Gilbert, J. R. (1995). Management (6th ed.). Prentice-Hall. John, M. K., Chimay, J. A., & Patricia, M. C. (2002). A CLEVER approach to selecting a knowledge management strategy. International Journal of Project Management, 20(2), 205211. Kalling, T. (2003). Knowledge management and the occasional links with performance. Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(3), 6781. Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Kim, Y. G., Yu, S. H., & Lee, J. H. (2003). Knowledge strategy planning: methodology and case. Expert Systems with Applications, 24(3), 295307. Koepfer, G. C. (2001). Playing global chess. Modern Machine Shop, 73(12), 10. Kreng, V. B., & Tsai, C. M. (2003). The construct and application of knowledge diusion model. Expert Systems with Applications, 25(1), 177186. Krogh, G., Nonaka, I., & Aben, M. (2001). Making the most of your companys knowledge: a strategic framework. Long Range Planning, 34(4), 421439. Lee, J.-H., & Kim, Y.-G. (2001). A stage model of organizational knowledge management: a latent content analysis. Expert Systems with Applications, 20(4), 299311.

S.-M. Tseng / Expert Systems with Applications 34 (2008) 734745 nchez, R. (2006). Ruiz-Mercader, J., Meron o-Cerdan, A. L., & Sabater-Sa Information technology and learning: their relationship and impact on organisational performance in small businesses. International Journal of Information Management, 26(1), 1629. Shaw, D., & Edwards, J. S. (2005). Building user commitment to implementing a knowledge management strategy. Information & Management, 42(7), 977988. Spender, J. C. (1996). Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the rm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(Special issue), 4562. Teece, D. J. (2000). Strategies for managing knowledge assets: the role of rm structure and industrial context. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 3554. The largest corporations in Taiwan Top 5000 (2005), China credit information service, LTD. Tiwana, A. (2001). The knowledge management toolkit: practical techniques for building knowledge management system. Prentice-Hall. Trappey, V. C., & Trappey, A. L. C. (2000). Electronic commerce in greater China. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 101(5), 201209. Wakeeld, R. L. (2005). Identifying knowledge agents in a KM strategy: the use of the structural inuence index. Information & Management, 42(7), 935945.

745

Wang, Z. (2003). WTO accession, the Greater China free-trade area, and economic integration across the Taiwan Strait. China Economic Review, 14(3), 316349. Wiig, K. M., Hoog, R. De., & Spek, Rob van der (1997). Supporting knowledge management: a selection of methods and techniques. Expert Systems with Applications, 13(1), 1527. Wong, K. Y., & Aspinwall, E. (2004). Characterizing knowledge management in the small business environment. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(3), 4461. Wong, K. Y., & Aspinwall, E. (2006). Development of a knowledge management initiative and system: a case study. Expert Systems with Applications, 30(4), 633641. Woo, J. H., Clayton, M. J., Johnson, R. E., Flores, B. E., & Ellis, C. (2004). Dynamic knowledge map: reusing experts tacit knowledge in the AEC industry. Automation in Construction, 13(2), 203207. Yim, N. H., Kim, S. H., Kim, H. W., & Kwahkc, K. Y. (2004). Knowledge based decision making on higher level strategic concerns: system dynamics approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 27(1), 143158. Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. B., & Parasuraman, A. (1988). Communication and control processes in the delivery of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 52(April), 3548.

You might also like

- Customer Relationship Management Project ReportDocument108 pagesCustomer Relationship Management Project Reportmohitalk2me75% (97)

- BSC Case Study Telecom FijiDocument35 pagesBSC Case Study Telecom Fijiiuliamaria18No ratings yet

- Supply Chain Performance Measurement ApproachesDocument273 pagesSupply Chain Performance Measurement ApproachesErik Van0% (1)

- A Project Report On Supply Chain ManagementDocument14 pagesA Project Report On Supply Chain Managementpragyaparul20% (5)

- MKT Balaji Wafer TybbaDocument65 pagesMKT Balaji Wafer TybbaPari Savla0% (1)

- PROJECT REPORT On HPCL - Collegeprojects1.Blogspot - inDocument49 pagesPROJECT REPORT On HPCL - Collegeprojects1.Blogspot - inPari SavlaNo ratings yet

- A Project On SubwayDocument114 pagesA Project On Subwayaster526275% (4)

- Experimental Psychology ActDocument5 pagesExperimental Psychology ActAlex BalagNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Measuring KM Performance Outcomes in Organisations (For AMHAZ)Document20 pagesCriteria For Measuring KM Performance Outcomes in Organisations (For AMHAZ)Georges E. KalfatNo ratings yet

- Chenhall2005 PDFDocument28 pagesChenhall2005 PDFsitirachmahNo ratings yet

- Knowlege Managment Strategies in Public SecotorDocument12 pagesKnowlege Managment Strategies in Public Secotoribrahim kedirNo ratings yet

- Mis Role & Importance, Corporate Planning of MISDocument6 pagesMis Role & Importance, Corporate Planning of MISBoobalan RNo ratings yet

- Article Image de MarqueDocument6 pagesArticle Image de MarqueDrilla BennaniNo ratings yet

- Intangible ResourcesDocument14 pagesIntangible ResourcesPat NNo ratings yet

- The Drivers and Measures of Success in High Performance OrganizationsDocument18 pagesThe Drivers and Measures of Success in High Performance Organizationsnnorissa8470No ratings yet

- Performance Measuresof Knowledge ManagementDocument6 pagesPerformance Measuresof Knowledge Managementsamuel petrosNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Among Knowledge Management, Organizational Learning, and Organizational PerformanceDocument13 pagesThe Relationship Among Knowledge Management, Organizational Learning, and Organizational PerformanceReema KapoorNo ratings yet

- A Theoretical Framework For Strategic Knowledge Management MaturityDocument17 pagesA Theoretical Framework For Strategic Knowledge Management MaturityadamboosNo ratings yet

- Balanced Scorecard Implementation Within A Malaysian Government-Linked CompanyDocument29 pagesBalanced Scorecard Implementation Within A Malaysian Government-Linked CompanyPui YanNo ratings yet

- Linking Strategic Objectives To OperationsDocument9 pagesLinking Strategic Objectives To Operations411hhapNo ratings yet

- Strategic Market Driven ISITPlanning Model Chapter 3Document22 pagesStrategic Market Driven ISITPlanning Model Chapter 3raiyanduNo ratings yet

- 2004 Brignall & Ballantine PDFDocument16 pages2004 Brignall & Ballantine PDFNico FuentesNo ratings yet

- Implementing Knowledge Management Systems in Public Sector Organisations: A Case Study of Critical Success FactorsDocument13 pagesImplementing Knowledge Management Systems in Public Sector Organisations: A Case Study of Critical Success FactorsHaldamir YavetilNo ratings yet

- The Use of Management Control Systems: Impact On Companies' PerformanceDocument31 pagesThe Use of Management Control Systems: Impact On Companies' PerformanceReddahi BrahimNo ratings yet

- 2A Impact of AIS On Org Perf. A Study of SMEs in The UAE EditDocument22 pages2A Impact of AIS On Org Perf. A Study of SMEs in The UAE EditAmirahNo ratings yet

- Customer-Focused Strategies and Information Technologycapabilities: Implications For Service Quality of Malaysian Local AuthoritiesDocument16 pagesCustomer-Focused Strategies and Information Technologycapabilities: Implications For Service Quality of Malaysian Local Authoritieslakshmijey123No ratings yet

- Jurnal 3 Selesai (PDF - Io)Document8 pagesJurnal 3 Selesai (PDF - Io)Ilhamputra287No ratings yet

- Effect of Knowledge Management Systems On Operating Performance An Empirical Study of Hi Tech Companies Using The Balanced Scorecard ApproachDocument11 pagesEffect of Knowledge Management Systems On Operating Performance An Empirical Study of Hi Tech Companies Using The Balanced Scorecard Approachمهنوش جوادی پورفرNo ratings yet

- Modelling The Value Adding Attributes of Real Estate To The Wealth Maximization of The FirmDocument33 pagesModelling The Value Adding Attributes of Real Estate To The Wealth Maximization of The FirmHaojie YangNo ratings yet

- Examining The Strategic Benefits of Information Systems: A Global Case StudyDocument17 pagesExamining The Strategic Benefits of Information Systems: A Global Case StudyRowdy RahulNo ratings yet

- A Generic System Dynamics Model of Firm Internal Processes: Hamed KhalediDocument23 pagesA Generic System Dynamics Model of Firm Internal Processes: Hamed KhalediKhalis MahmudahNo ratings yet

- Critical Success Factors For ERP Systems Implementation in Public AdministrationDocument19 pagesCritical Success Factors For ERP Systems Implementation in Public AdministrationShah Maqsumul Masrur TanviNo ratings yet

- Measuring Success of Accounting Informat PDFDocument10 pagesMeasuring Success of Accounting Informat PDFJean Diane JoveloNo ratings yet

- The Role of Behavioral Factors and National CulturDocument25 pagesThe Role of Behavioral Factors and National CulturPriyaNo ratings yet

- 042 Performance Measurement Practices of Public Sectors in MalaysiaDocument15 pages042 Performance Measurement Practices of Public Sectors in MalaysiaJona Maria MantowNo ratings yet

- Performance Management Effectiveness Lessons From World Leading FirmsDocument19 pagesPerformance Management Effectiveness Lessons From World Leading FirmsziajehanNo ratings yet

- Chen, Chen 2005Document22 pagesChen, Chen 2005Ranion EuNo ratings yet

- Complementary Controls and ERP Implementation SuccessDocument23 pagesComplementary Controls and ERP Implementation Successtrev3rNo ratings yet

- Pre-Publication Version Please Cite AsDocument28 pagesPre-Publication Version Please Cite Asmamun khanNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 The Impact of Accounting Information System On Organisational Performance in ChinaDocument16 pagesPaper 2 The Impact of Accounting Information System On Organisational Performance in Chinajanz suarezNo ratings yet

- Impact of Strategic Management Practices On Organizational Performance - Empirical Sudies Os Selesct Firms in LibyaDocument18 pagesImpact of Strategic Management Practices On Organizational Performance - Empirical Sudies Os Selesct Firms in LibyaAliceClaytonNo ratings yet

- Framework Review PerformanceDocument31 pagesFramework Review PerformanceTabitaNo ratings yet

- Practical Application of Balanced Scorecard - A Literature ReviewDocument17 pagesPractical Application of Balanced Scorecard - A Literature ReviewPrijoy JaniNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Human Resource Management PracticesDocument21 pagesThe Impact of Human Resource Management Practicessanzida akterNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management For Continuous Improvement: Frances Jørgensen, Bjørge Timenes Laugen and Harry BoerDocument13 pagesHuman Resource Management For Continuous Improvement: Frances Jørgensen, Bjørge Timenes Laugen and Harry Boermeher7No ratings yet

- 2 - AlnajjarDocument19 pages2 - AlnajjarWHILSA PUTRA MUTHINo ratings yet

- Performance Management Jane Maley: Intended Learning OutcomesDocument34 pagesPerformance Management Jane Maley: Intended Learning OutcomesAindrila BeraNo ratings yet

- Information Technology in Construction: 2. Materials, Equipment and MethodsDocument11 pagesInformation Technology in Construction: 2. Materials, Equipment and MethodsAnil SanganNo ratings yet

- Performance Management System The Practices in The Public Organization in The Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesPerformance Management System The Practices in The Public Organization in The Developing CountriesErik MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Managers' Perception of Potential Impact of Knowledge Management in The Workplace: Case StudyDocument8 pagesManagers' Perception of Potential Impact of Knowledge Management in The Workplace: Case StudyUsman RashidNo ratings yet

- TQM and Org PerformanceDocument11 pagesTQM and Org PerformanceRashid JehangiriNo ratings yet

- Identification of Critical Success Factors For Total Quality Management Implementation in Organizations: A Critical ReviewDocument7 pagesIdentification of Critical Success Factors For Total Quality Management Implementation in Organizations: A Critical ReviewRashid JehangiriNo ratings yet

- Business Intelligence Effectiveness and Corporate Performance Management: An Empirical Analysis PDFDocument29 pagesBusiness Intelligence Effectiveness and Corporate Performance Management: An Empirical Analysis PDFM5991No ratings yet

- Competitive Strategy Performance MeasurementDocument14 pagesCompetitive Strategy Performance MeasurementKim JaeneeNo ratings yet

- Adding Value Through HR - Reorienting HR Measurement To Drive Business PerformanceDocument16 pagesAdding Value Through HR - Reorienting HR Measurement To Drive Business PerformanceTeddy SiuNo ratings yet

- Balance Scorecard Implementation Case StudyDocument10 pagesBalance Scorecard Implementation Case StudyAnonymous AGkPX6No ratings yet

- Critical Success Factors For Implementing Knowledge Management in Small and Medium EnterprisesDocument19 pagesCritical Success Factors For Implementing Knowledge Management in Small and Medium Enterprisesnataliapw_004No ratings yet

- The Priority Factor Model For Customer Relationship Management System SuccessDocument3 pagesThe Priority Factor Model For Customer Relationship Management System SuccessBruna DiléoNo ratings yet

- Article 1: Enterprise Resource Planning and Business Model Innovation: Process, Evaluation and OutcomeDocument8 pagesArticle 1: Enterprise Resource Planning and Business Model Innovation: Process, Evaluation and OutcomeSonal GuptaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Competency Mapping and Its Impacton Deliverables With Respect To The Reality SectorDocument12 pagesA Study On Competency Mapping and Its Impacton Deliverables With Respect To The Reality SectorNITIN SINGHNo ratings yet

- Trends in PMSDocument14 pagesTrends in PMSMUSKAN CHHAPARIA 2127747No ratings yet

- Review of LiteratureDocument3 pagesReview of LiteratureSai LahariNo ratings yet

- Ratingless Performance Management: Innovative Change to Minimize Human Behavior RoadblocksFrom EverandRatingless Performance Management: Innovative Change to Minimize Human Behavior RoadblocksNo ratings yet

- Summary of Brian E. Becker, David Ulrich & Mark A. Huselid's The HR ScorecardFrom EverandSummary of Brian E. Becker, David Ulrich & Mark A. Huselid's The HR ScorecardNo ratings yet

- Plastic Money Full ProjectDocument54 pagesPlastic Money Full ProjectNevil Surani76% (169)

- Project On Hamam SoapDocument60 pagesProject On Hamam SoapRoyal Projects94% (16)

- A Project Report On Employee MotivationDocument72 pagesA Project Report On Employee MotivationNoor Ahmed64% (25)

- MonginisDocument79 pagesMonginisHarsh Savla100% (2)

- Franchise BrochureDocument3 pagesFranchise BrochurePari SavlaNo ratings yet

- Com Part IveDocument92 pagesCom Part IvePari SavlaNo ratings yet

- Women and DevelopementDocument8 pagesWomen and DevelopementPari SavlaNo ratings yet

- Managing Educational Policy in Nigerian Higher Education Implications For Effective PracticesDocument9 pagesManaging Educational Policy in Nigerian Higher Education Implications For Effective PracticesPUBLISHER JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Very FinalDocument37 pagesVery Finalabegailgaray32No ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Work Team Strategy by Using The SWOT AnalysisDocument7 pagesEvaluation of A Work Team Strategy by Using The SWOT AnalysisAnubhav dasNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Cross-Functional Sales Performance Variables in It/ItesDocument17 pagesDeterminants of Cross-Functional Sales Performance Variables in It/ItesHanchalu LikesaNo ratings yet

- Parametric and Non ParametricDocument4 pagesParametric and Non ParametricNadia Thaqief100% (2)

- S1 2013 PDFDocument10 pagesS1 2013 PDFMonesh PadyachiNo ratings yet

- Conflict Resolution Skills and Marital SatisfactionDocument14 pagesConflict Resolution Skills and Marital SatisfactionCristiana Oprișescu100% (1)

- T TestsDocument6 pagesT Testsapi-3774614No ratings yet

- Impact of Demographics On OnlineDocument6 pagesImpact of Demographics On Onlinemanjusri lalNo ratings yet

- Asynchronous Voice Conferencing Anxiety by Poza 2011Document31 pagesAsynchronous Voice Conferencing Anxiety by Poza 2011nayarasalbegoNo ratings yet

- 2-Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) For Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Adhd)Document12 pages2-Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) For Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Adhd)Clinical and Counselling Psychology ReviewNo ratings yet

- Statistical Analysis NotesDocument49 pagesStatistical Analysis NotesNissy Nicole FaburadaNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Essentials of Statistics For The Behavioral Sciences 4th by NolanDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Essentials of Statistics For The Behavioral Sciences 4th by Nolanrestategobbet3fq5f100% (52)

- Teaching Phrasal Verbs More Efficiently: Using Corpus Studies and Cognitive Linguistics To Create A Particle ListDocument16 pagesTeaching Phrasal Verbs More Efficiently: Using Corpus Studies and Cognitive Linguistics To Create A Particle ListElaine NunesNo ratings yet

- Debi Uas Statistik WordDocument12 pagesDebi Uas Statistik Wordariowahyuw94No ratings yet

- RDC - Thesis and Dissertation IMRAD Format 1Document151 pagesRDC - Thesis and Dissertation IMRAD Format 1DENVER ALIGANo ratings yet

- Reporting: by Mohammed NawaisehDocument43 pagesReporting: by Mohammed NawaisehLayan MohammadNo ratings yet

- Sta404 TemplateDocument11 pagesSta404 TemplateAinnatul Nafizah Ismail- 2276No ratings yet

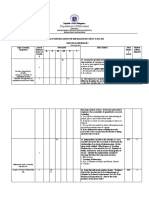

- Division of PampangaDocument31 pagesDivision of PampangaRICHARD BAIDNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 Diagnostic Test Tos 2022Document16 pagesPractical Research 2 Diagnostic Test Tos 2022Rommel ObilloNo ratings yet

- ACFrOgDvPXMbgn-8KJn3MpIEqU7Ac6nsCWNjLhSoJ9U8NhVwZ56PBEBGQRZVkI8 WrSFP9M yuGJZWe3EiqY5z5ZupkpgRoSyaipeRU9g3Dn21k5S4Nxfmp8TFDJehxlpedHUouBv QGn0geh1fpDocument9 pagesACFrOgDvPXMbgn-8KJn3MpIEqU7Ac6nsCWNjLhSoJ9U8NhVwZ56PBEBGQRZVkI8 WrSFP9M yuGJZWe3EiqY5z5ZupkpgRoSyaipeRU9g3Dn21k5S4Nxfmp8TFDJehxlpedHUouBv QGn0geh1fpSYAZANA FIRAS SAMATNo ratings yet

- Nonparametric Pairwise Multiple Comparisons in Independent GroupsDocument12 pagesNonparametric Pairwise Multiple Comparisons in Independent GroupsDiegoNo ratings yet

- 4 Pretest and Posttest AnalysisDocument6 pages4 Pretest and Posttest AnalysisRonnie NaagNo ratings yet

- Inferential Statistics For Data ScienceDocument10 pagesInferential Statistics For Data Sciencersaranms100% (1)

- Industrial Hygiene Statistics: Logprobability Plot and Least-Squares Best-Fit LineDocument1 pageIndustrial Hygiene Statistics: Logprobability Plot and Least-Squares Best-Fit LineSandra M.No ratings yet

- IJSRDocument5 pagesIJSRDani PhilipNo ratings yet

- SPSS Practice Problems - TTest PDFDocument2 pagesSPSS Practice Problems - TTest PDFaaaaasssNo ratings yet

- Final Paper QuantitativeDocument32 pagesFinal Paper QuantitativeLacanaria, Sandra G.No ratings yet