Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons: Cash and Vouchers

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons: Cash and Vouchers

Uploaded by

Urban Food SecurityCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- ERP Flow Chart GeneralDocument5 pagesERP Flow Chart Generalhendro irwansyahNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Potential WFP G2P Partner Programs in IndonesiaDocument34 pagesAssessment of Potential WFP G2P Partner Programs in IndonesiaJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Gender Equality and Food Security: Women's Empowerment As A Tool Against HungerDocument114 pagesGender Equality and Food Security: Women's Empowerment As A Tool Against HungerJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Hazard Map Myebon Kyaukphyu Ramrees Flood Area 03 Aug 2015 JPJXDocument1 pageHazard Map Myebon Kyaukphyu Ramrees Flood Area 03 Aug 2015 JPJXJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

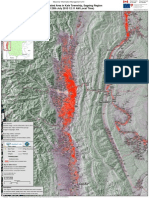

- Myanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Document1 pageMyanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP Uganda and Burkina Faso's Trial To Reduce Post-Harvest Losses For Smallholder FarmersDocument4 pagesWFP Uganda and Burkina Faso's Trial To Reduce Post-Harvest Losses For Smallholder FarmersJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Typhoon Haiyan Damage Summary Manila Philippines, Global Agriculture Information Netowrk (GAIN), USDA/FAS, Dec 4, 2013Document3 pagesTyphoon Haiyan Damage Summary Manila Philippines, Global Agriculture Information Netowrk (GAIN), USDA/FAS, Dec 4, 2013Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Vanuatu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report #5 23 Mar 2015Document2 pagesVanuatu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report #5 23 Mar 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP Kenya's Transitional Cash Transfers To Schools (TCTS) : A Cash-Based Home Grown School Meals ProgrammeDocument4 pagesWFP Kenya's Transitional Cash Transfers To Schools (TCTS) : A Cash-Based Home Grown School Meals ProgrammeJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP 2012 Update of Safety Nets Policy - The Role of Food Assistance in Social ProtectionDocument29 pagesWFP 2012 Update of Safety Nets Policy - The Role of Food Assistance in Social ProtectionJeffrey Marzilli100% (1)

- UNHCR 2009 Policy On Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban AreasDocument30 pagesUNHCR 2009 Policy On Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban AreasJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Setting The Right Priorities Protecting Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Afghanistan - Watchlist 2010Document60 pagesSetting The Right Priorities Protecting Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Afghanistan - Watchlist 2010Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- UNICEF Report: The Out-of-School Children of Sierra LeoneDocument77 pagesUNICEF Report: The Out-of-School Children of Sierra LeoneJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP Oxfam Gaza Cash Voucher Programme ReviewDocument54 pagesWFP Oxfam Gaza Cash Voucher Programme ReviewJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Forced Migration Review, Issue 34: Adapting To Urban DisplacementDocument76 pagesForced Migration Review, Issue 34: Adapting To Urban DisplacementUrban Food SecurityNo ratings yet

- WB Targeting Assessment of Cash Transfer Program in Gaza and West BankDocument23 pagesWB Targeting Assessment of Cash Transfer Program in Gaza and West BankJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Fill in The Gaps With A An The or Zero ArticleDocument3 pagesFill in The Gaps With A An The or Zero Articlekamolpan@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- IPENZ PN19-SeismicResistancePressureEquipmentFinalDocument138 pagesIPENZ PN19-SeismicResistancePressureEquipmentFinalnikhil0104No ratings yet

- Kijko & Graham - Pageoph, 1998 - Parametric-Historic PSHA Procedure I PDFDocument31 pagesKijko & Graham - Pageoph, 1998 - Parametric-Historic PSHA Procedure I PDFCamilo LilloNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law Cases DigestDocument32 pagesTransportation Law Cases DigestAngelo Igharas InfanteNo ratings yet

- Possible Failure Point Emerges in Miami-Area Building Collapse - The New York TimesDocument5 pagesPossible Failure Point Emerges in Miami-Area Building Collapse - The New York TimesMrMasterNo ratings yet

- Dhs Bib - Web Version - Final 508Document112 pagesDhs Bib - Web Version - Final 508jasonjasonNo ratings yet

- Caoch SWOT AnalysisDocument5 pagesCaoch SWOT Analysisyantao318No ratings yet

- KR CC: I MPA-018 I Master of Arts (Public Administration) Term-End Examination June, 2018 Mpa-018: Disaster ManagementDocument4 pagesKR CC: I MPA-018 I Master of Arts (Public Administration) Term-End Examination June, 2018 Mpa-018: Disaster ManagementAnushka SinghNo ratings yet

- Landslide 2Document16 pagesLandslide 2Prince JoeNo ratings yet

- Maritime CommerceDocument40 pagesMaritime CommerceDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- LEEA New Rigging ManualDocument106 pagesLEEA New Rigging ManualAkramKassisNo ratings yet

- Emergency Response and Disaster Management Plan (Erdmp)Document25 pagesEmergency Response and Disaster Management Plan (Erdmp)Dinesh KanukolluNo ratings yet

- Calculate Earthquake Forces On Buildings and StructuresDocument5 pagesCalculate Earthquake Forces On Buildings and StructuresMelvin EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Climatechange ThesisDocument46 pagesClimatechange ThesisMinaNo ratings yet

- ADMS SimulationDocument2 pagesADMS Simulationacbien2No ratings yet

- Fire Incident at AMRI Hospital Kolkata PDFDocument5 pagesFire Incident at AMRI Hospital Kolkata PDFvikaspisalNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 Module 4 Understanding TyphoonDocument2 pagesQuarter 2 Module 4 Understanding Typhoonperrypetersonramos38No ratings yet

- Supervisory Policy Manual: TM-G-2 Business Continuity PlanningDocument19 pagesSupervisory Policy Manual: TM-G-2 Business Continuity PlanningYYY CCCNo ratings yet

- TragedyDocument3 pagesTragedySONANo ratings yet

- Đề 3Document7 pagesĐề 3Nguyễn VyNo ratings yet

- Transportation LawDocument61 pagesTransportation LawHelena Herrera100% (2)

- Climate of MumbaiDocument3 pagesClimate of MumbaiSheila J LowryNo ratings yet

- Eng21 (Story of Hamguchi Gohei)Document9 pagesEng21 (Story of Hamguchi Gohei)Alapan NandaNo ratings yet

- Weather TerminologiesDocument7 pagesWeather TerminologiesJ CNo ratings yet

- Tragedy & Common ManDocument3 pagesTragedy & Common ManbiffbiffordNo ratings yet

- Aycock - Shakespeare, Boito and VerdiDocument18 pagesAycock - Shakespeare, Boito and VerdiOlga SofiaNo ratings yet

- Accident QuizDocument15 pagesAccident QuizmujayanahNo ratings yet

- Sitxwhs003 Learner Guide v1.2 AcotDocument90 pagesSitxwhs003 Learner Guide v1.2 AcotKomal SharmaNo ratings yet

- VolcanoDocument59 pagesVolcanoJhanna Mae HicanaNo ratings yet

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons: Cash and Vouchers

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons: Cash and Vouchers

Uploaded by

Urban Food SecurityCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons: Cash and Vouchers

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons: Cash and Vouchers

Uploaded by

Urban Food SecurityCopyright:

Available Formats

Cash and Vouchers

Introduction

Most of WFP's resources these days are in cash. Over 90% of this goes to cover costs of food or food transport. Only about 2% is currently used for cash or voucher distribution, but the amount is expected to rise. By the end of 2009 WFP had used cash transfers or vouchers in 20 pilot activities. The Top 10 Lessons here are synthesized from 18 WFP evaluations since 2001 of WFP operations across the globe that included a cash and voucher component, as well as 2 assessments conducted by others that included WFP operations, and other internal sources. These lessons are provisional: the empirical base is limited and WFPs involvement in the cash and voucher component was also often indirect. The 'Top 10 Lessons' series is intended to be of practical value, primarily to field staff, in planning and implementing WFP operations. Drawn from evaluations of past operations, they summarise ways to tackle 10 key challenges that have been encountered by others before on a selected topic. They are not policy directives, but have been compiled within the current policy framework and are in line with WFP's mission and mandate.

Background

WFP is primarily a cash organization, from a resources perspective. The major part of WFPs resources these days (and since well over a decade) is in cash, rather than in the form of inkind foodstuffs. Most of this cash is used to pay for food transport and logistics costs, international, regional and local food procurement and various operational support and overhead costs. Very little (less than one percent of total WFP resources1) is currently used for direct cash or cash voucher distributions to beneficiaries, although the amount may be expected to rise in the future. According to the most recent data (March 2009), WFP has had or has a total of 24 past, current and

1

2 0 1 1

planned cash transfer and cash voucher initiatives in 18 countries and most of these were or are modest in size and short term, being typically of three months to a year in duration2. Of the 24 initiatives, eight initiatives (in six countries) have been completed, four are ongoing, one is about to start, four are at the design stage, two are undergoing a feasibility study and five are under consideration. Countries with more than one initiative are: Bangladesh, Georgia, Malawi and Nepal. Total beneficiaries listed against these 24 operations are less than a million people, though not all caseloads have been specified, many proposals being still at the feasibility or consideration stage.

According to the Annual Performance Report for 2007, WFP resources for that year were US$2.7 billion. The Annual Performance Report for 2008 was not yet available at the time of writing this paper.

The exception is the Pakistan cash-based food voucher programme which has been running for some 14 years, from 1994 to date. The shortest was in Myanmar and was abandoned after two weeks, at government request.

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

Although the overlap between the 12 completed or ongoing WFP cash initiatives in eight countries and OEDE evaluations is limited to just two countries (Malawi and Sri Lanka), OEDE evaluations have examined the cash issue in other countries or regional operations where the option has been considered (e.g. Aceh/Indonesia) or where other partners are involved (e.g. Ethiopia). Eighteen OEDE evaluations undertaken in the period 2001 to 2009 have some mention of the cash debate, though the coverage is sometimes cursory and empirical findings are limited. This is possibly because WFP was not usually directly involved in such initiatives and the cash issue was not usually a major focus of the evaluation missions Terms of Reference3. A Technical Meeting on Cash in emergencies and transition held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2006 provides a useful insight into the debate, at that time, on the issue. Seven WFP country case studies were presented at the meeting, of which four (Georgia, Malawi, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) had direct WFP involvement and three (Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Zambia) had cash transfers in which they were part of a broader response in which WFP provided food. Following this meeting, a Cash and Food was issued by WFP in 2007 and a Policy paper the

3

subsequent year. WFP is currently preparing operational guidelines on cash transfer programming4. Current work on enhancing WFPs capacity for cash and voucher transfer programmes includes significant resources to enhance the evidence base to inform decision making processes regarding cash and vouchers. In addition, future OEDE evaluations will focus on cash interventions in operations where these are a feature and a strategic evaluation of WFPs experience with cash interventions may follow. Since its creation in the early 1960s, WFP has been involved with some cash operations in the field, although these have been of a different nature to the current approach. Past operations have included direct or indirect monetization of imported foodstuffs to support national development objectives5 or food entitlement programmes and programmes, where WFP has provided food aid to labourers, as a counterpart or supplement to their cash wage

44

ICRC-IFRC, Oxfam/GB and ACF have already produced comprehensive guidelines on cash programming.

5

For example, the large Operation Flood programme in India in the 1970s and 1980s which funded national dairy development through sales of reconstituted liquid milk produced with imported dried skimmed milk and butteroil.

These 22 OEDE evaluations are listed at the end.

Lesson 1: Food and cash interventions can complement each other in a national assistance programme.

Summary: Cash and food aid resources can complement each other successfully and be mutually reinforcing. Criteria used to decide on whether cash or food is more appropriate and to find the optimum balance must be responsive to geographic, livelihoods and seasonal factors as well as market conditions. Experiences from the field: The 2007 evaluation of the Ethiopia PRRO noted how WFP food aid supported the larger Government of Ethiopia Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP), where the major part (70%) of resources was in the form of cash from other donors (Full Report of the Thematic Review of Targeting in WFP Relief Operations)6. According to the report,

6

Although actual programming levels of cash in recent years may have been lower than indicated by this figure of 70%. According to the WFP Cash and Food Transfers Primer, as of late 2006 the cash-food split was around 50-

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

all donors and government informants agreed that the debate was no longer about cash or food, but rather about finding the optimum balance to best fit local livelihood and market realities and how this might change seasonally and annually, according to the wide socio-economic environment. There was a need for a more systematic decision making to inform such cashfood programming and a framework for decision making based on objective analysis of empirical evidence needed to be developed, with WFP involvement. The phased replacement of food aid by cash was expected to gradually improve market elasticity and to impact on the duration of the initial lag period on local markets (in which supply fails to adequately reflect demand). More research was needed, however, on this aspect, as well as on the role of WFP local purchases within the PSNP and on the differing effects of food and cash injections on market supply and prices, depending on size of distributions, time of year and market linkages. An earlier (2001) evaluation of the Ethiopia Country Programme had put forward an argument for continued food for work, based on the fact that per capita domestic food production in Ethiopia continued on a downward trend and that the average family ran out of self-produced food months before a new crop was available. It also observed that when cash for work is provided in ways that target only the poorest of the poor, daily wage rates have to be set below prevailing market wages, with the result being inadequate income for enabling the purchase of sufficient food, as the food is usually transported from food surplus areas, with high transport costs. The 2004 evaluation of the Afghanistan PRRO reported that the interim government and donors had criticized the large volumes of relief food aid and expressed a preference for cashbased interventions. The evaluation mission recommended that joint cash-food interventions be field tested, and that cash interventions would be appropriate among households in food surplus

50, with several woredas switching from cash to food and vice versa (section 3.4, page 15).

areas and on the fringes of major cities. The Southern Africa PRRO evaluation of late 2006 concluded that in most cases of acute and chronic food insecurity, food aid was a suitable measure, but that cash or a combination of cash and food could be more appropriate in some circumstances, where internal food markets are functioning well. At that time of the evaluation a number of cash interventions were being initiated in the southern Africa region, but the results were not yet known. The Madagascar PRRO evaluation of 2008 noted that cash for work and food for work could be employed in the country, in different zones, according to levels of remoteness and access, with food aid being more appropriate in the remote areas. Other sources: According to the Addis Abeba Technical Meeting report of 2006, mentioned earlier, little was then understood about if and how cash and food transfers might be productively combined. Such a combination could be in the context of a particular initiative i.e. blending in both space and time or it might occur in phases within the context of long-term social protection strategies featuring sustainable safety nets. There were strong theoretical arguments and partial empirical evidence supporting the notion that rather than being competitive alternatives, food and cash might be complementary and mutually reinforcing instruments for addressing food and nutrition insecurity. It observed that progress in resolving controversial operational issues likely depended on enhanced understanding of such middle ground options. According to the WFP Cash and Food Transfers Primer, cash transfers are more appropriate (and to generate maximum benefit) right before and during harvests, conversely, food transfers are preferred during the period when household food grain stocks have been consumed or sold and grain must be purchased from the market. This and other factors (some mentioned further in this paper, such as geographic location

3

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

and gender) are said to provide a solid argument for looking at cash and food as complementary and mutually reinforcing transfers, rather than as rigid alternatives. The Primer quotes three recent

external sources for this finding7.

7

See Section 3.5 on page 16 of the Primer.

Lesson 2: Recurrent national food deficits and fragile supply chains between importing traders and local markets may argue for a role for food aid rather than cash.interventions.

Summary: Providing cash, particularly in relief situations, may put a strain on local food supply chains when a country is food deficit and dependent on imports for a significant part of its food supply, particularly cereals. Importing traders may not have time to build up their stocks if there is a sudden deterioration in the harvest situation (due to sudden failure of the rains, floods, locust infestation etc). Also, the supply chain between the sea port or border point of entry and the local markets may be fragile, due to poor road conditions, deteriorated infrastructure, insecurity etc. Some of these delivery problems could also affect imported food aid supplies, however Experiences from the field: The 2001 evaluation of the Somalia PRRO observed that Somalia was an exceptionally expensive country in which to deliver food aid and that WFP Somalia was conscious of the need to justify aid in the form of food. Some donors and NGOs argued that it would make more sense to give people money to buy local food, whether as cash for relief or cash for work. At the time of the evaluation, however, the proposal had not been substantially tested by donors or aid agencies. The country as a whole was food deficit in any year, however, so a significant quantity of food had to be imported. Also, populations in many locations were isolated from customary markets. The demand chain between local market and importing trader was often fragile at best. This was especially true of insecure areas of the south and/or populations distant from market centres, which accounted for a good part of the rural population. The evaluation mission concluded that money in hand is not the same as food in hand. On the other hand, several agencies have experimented with cash programmes in Somalia, often using traditional money transfer channels, with apparently good results, although these may be on a relatively modest scale in the overall scheme of things. It appears that Somalia was an early testing ground for cash approaches on the part of a number of NGOs8. Other sources: The WFP Cash and Food Transfers Primer notes that cash provides people with choice but it also transfers to them the risk of supply failures and that utmost attention needs to be paid to careful market monitoring and assessment

8

See the Somalia section of the Real Time Evaluation of WFP s response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami.

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

Lesson 3: Cash transfers may lead to inflation of local food prices, especially in fragmented or poorly functioning markets.

Summary: The lack of integrated markets could mean that a new imported subsidized cash demand for food could lead to inflation of local food prices, especially if there are seasonal market shortages and the cash transfers are significant. Also, setting a money ration intended to equate for any reasonable planning period to a minimum purchased food basket could prove to be problematic, due to price fluctuations.

Experiences from the field: The Somalia evaluation mentioned under Lesson 2, above, observed that local market price inflation could be a potential problem with cash interventions, particularly if implemented on a large scale. The external (non-OEDE) joint evaluation of WFPs Enabling Development policy of 2004 was concerned that there was no sure understanding of what might happen if there was a significant injection of cash into a country or region, in terms of its impact on local market prices and cited Ethiopia as a country of interest in this respect. The Zimbabwe section of the Southern Africa regional PRRO evaluation of late 2006 noted that food for work, training and assets had been seriously questioned in Zimbabwe and suggestions made that cash disbursements would be more appropriate for beneficiaries and more cost effective. The evaluation team concluded that, given the issues of hyper-inflation and the difficulties in purchasing maize on the commercial market, in part due to the role of the marketing boards at that time, food aid in support

of agricultural and livelihood activities continued to be an appropriate option. In areas where markets are functioning well (or beginning to function well again after a sudden natural disaster), such as in Aceh, Indonesia, however, cash interventions did not seem to have any particular inflationary effect, as noted in the evaluation of the Indonesia PRRO in 2006. Other sources: The WFP Cash and Food Transfers Primer noted that only a small fraction of the experience with cash approaches had been tested in riskier, marginalized and chronically food-insecure rural areas, where markets may be more fragile. The Oxfam Decision Tree reproduced as Figure 5 on page 11 of the Primer is designed to help analysts and programming staff to make decisions related to markets. Support to markets, through infrastructure improvements (access roads, bridges, market structures) and support to traders (contractual agreements, transport) may help to improve the domestic food supply chain and market performance.

Lesson 4: Cash may be more appropriate where there is good market access; food may be more appropriate in remote areas with difficult market access.

Summary: Cash transfers or vouchers may be more appropriate in areas with good market access. Food interventions may be more appropriate in remote areas with difficult market access. Surveys of populations in these different areas tend to confirm this hypothesis. However, measures can be taken to help improve market access. Experiences from the field: According to the Afghanistan PRRO evaluation, government agency findings regarding peoples preference for food for work versus cash for work revealed

5

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

that the preference for food instead of cash was higher among the poor and poorest than among the less poor and that food aid was preferred in remote areas with difficult market access, especially during the winter season when it was difficult to buy food in the market, as mountain passes were blocked by snow. Among food secure households in food surplus areas and on the fringes of major cities, the preference was for cash for work9. On this issue, as on others, care has to be taken to avoid interview bias through the introduction of leading questions and taking into account that interviewees may fear that a certain type of assistance may be withdrawn if they appear to give a negative assessment of that assistance. The Tajikistan PRRO evaluation of 2006 came to a similar conclusion, noting that food aid continued to be relevant as a tool for infrastructure construction or rehabilitation in food deficit areas with limited access to markets and for poor people with limited access to land. It stated that in highly food insecure districts, beneficiaries were keen to get food for work opportunities despite the low value of food rations relative to daily wages. It noted, however, that cash for work would be more efficient in geographic areas with good market access, taking into account the alpha value of the food rations. The Sudan/Darfur emergency operation evaluation of 2006 concluded that in the case of Darfur distributing cash instead of food was not an alternative, as there was simply not enough food on the Darfur markets to meet the needs. Recipients had to exchange some of their food to cover milling costs, however, and the evaluation mission suggested that WFP could have supported milling or reduced the need for food

9

sales by providing more commodities (such as sugar) with high sales value in the local market. The Zambia section of the Southern Africa regional PRRO evaluation of late 2006 concluded that cash transfers were appropriate in areas with functioning markets where the traders could respond to the increase in demand, while food transfers were found to be appropriate in areas with low stocks and weak market performance. The Madagascar PRRO evaluation of 2008 came to a similar conclusion on this issue. Other sources: Related to the Afghanistan findings, a report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) on Bangladesh noted that the results of their study suggested that, as income increases, beneficiary preference for food declines. Better-off beneficiaries tend to prefer only cash. The IFPRI assessment in Sri Lanka found that cash receiving households are more likely to eat less basic staple and spend on improving the diversity of their diet (e.g. with meat and dairy products, processed foods and more expensive cereals) and on clothing and footwear. In the poorest households, this can lead to lower calorie intake, partly because they have lowest household liquidity and partly because they tend to be living in areas with less well functioning markets. Figure 6 on page 16 of the WFP Cash and Food Transfers Primer notes geographic location as one of three main considerations in terms of beneficiary preferences for food or cash. People living in remote areas distant from main markets tend to prefer food transfers, while proximity to markets makes it easier to spend cash on the desired goods10.

10

On this issue, as on others, care has to be taken to avoid interview bias through the introduction of leading questions and taking into account that interviewees may fear that a certain type of assistance may be withdrawn if they appear to give a negative assessment of that assistance.

Based on Devereux.S, Cash Transfers and Social Protection. Paper prepared for SARPN-RHVP-Oxfam workshop on Cash Transfer Activities in Southern Africa, Johannesburg, 2006.

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

Lesson 5: Food aid may be needed in the first period after a sudden natural disaster, until local markets are functioning again. Then cash interventions may be more appropriate.

Summary: When markets are destroyed by a sudden natural disaster, such as an earthquake, tsunami, hurricane or floods, food aid may be a more appropriate response than cash until such time as markets have had time to recover and are functioning again. This may be especially true where the destruction is extensive and market hubs have been affected Experiences from the field: During the response to the Indian Ocean tsunami, in late 2004-early 2005, there was much discussion of the relative merits of food as compared to cash interventions. The tsunami relief operation attracted a large number of agencies, particularly to Aceh/Indonesia, and was cash rich. It had one of the highest cash responses in recent relief operation history, with significant donations from the general public11. Partly for this reason and because the Indonesian national and regional food markets were responsive to demand, several agencies, such as Oxfam, argued for more cash interventions, rather than food aid. In its section on the overall assessment of the appropriateness of food aid in the tsunami response, the report of the Real Time Evaluation of WFPs response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami concluded that while people needed food aid in the first weeks or months after the tsunami in Aceh province, once initial needs had been met and markets were beginning to function normally, there was a strong case for replacing food rations with a far wider variety of responses, including a greater cash component, which could be fine-tuned to

11

meet the needs of different people in different locations. The evaluation team believed that cash interventions could have worked along the less damaged eastern coast, while food interventions would have been more appropriate along the remoter and more severely affected western coast. The evaluation team observed, however, that agencies involved in cash interventions were facing challenges in scaling up their operations and even the combined efforts of the two major agencies involved were only reaching about thirteen percent of those receiving general food distributions at the time of the missions visit in May 2005, five months after the tsunami struck. In respect of food aid, the evaluation team also noted that it was not just the amount of food provided, but the reliability of distributions that were stressed by many of the recipients in Aceh as contributing to their sense of security. Other sources: The report on the Addis Ababa Technical Meeting of 2006 concluded that cash may not be appropriate in the immediate aftermath of an emergency (first 1-3 months) and more research is needed to better understand the potential of cash in different emergency contexts (slow/rapid onset; natural/complex ones).

To be noted in this connection is that WFP food aid (including the significant amount of food purchased locally or regionally by WFP) represented only about 5% of the total response to the tsunami, which is unusual for a relief operation.

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

Lesson 6: Food for work for the rehabilitation of agricultural production may be preferable until production has resumed. Then cash for work may be preferred.

Summary: In some countries recipients have expressed a preference for food aid while they rehabilitate their productive agricultural assets, until such time as they are able to grow food crops to provide for their basic food needs. Thereafter, cash for work or other cash support interventions may be more appropriate. Experiences from the field: In Rwanda, the Dutch Cooperation was providing cash for work, while WFP was providing food for work for similar activities and a debate on which strategy to adopt for future rehabilitation schemes had been opened. The Rwanda portfolio evaluation of 2004 concluded that WFP food assistance was appropriate until agricultural terraces had been constructed and again cultivated, while cash could be more appropriate thereafter or for parallel activities that were not directly linked to terrace rehabilitation. It recommended that tripartite contractual agreements between the concerned parties should specify the most appropriate type of remuneration, taking into account beneficiary preferences. According to the evaluation team, food aid was appreciated by beneficiaries for the rehabilitation phase. The Angola Relief and Recovery Operations portfolio evaluation of 2005 observed that as food security improved and overall availability of food within communities increased, the attraction of food as payment for work declined. A number of Implementing Partners interviewed declared that beneficiary interest in food for work or food for assets usually waned within two years of resettlement. In some provinces, UNHCR had to supplement food for work with cash payments. Also, related to the above, according to the Indonesia PRRO evaluation of 2006, in the coastal areas of Aceh/Indonesia there was an upturn in labour opportunities some months after the tsunami hit, with a corresponding decline in interest for baseline food for work ration payments that did not compare well with the cash labour equivalent. There was some concern, however, that too high a daily cash rate under cash for work operations could distort local labour markets12.

12

According to the evaluation report (16), UNDPs cash for work programme was covering only 13,000 people in May 2005. Oxfam reported in June that it was employing 62,500 people, but often for only 15 days a month.

Lesson 7: The gender implications of food and cash transfers are context specific and should be carefully assessed and monitored.

Summary: There are different findings on gender implications of food and cash programming, depending on cultural and other contexts. In some cases women preferred food aid over cash, as they felt that they had more control over food entitlements, whereas men were said to appropriate cash, sometimes for non-essential commodities, such as alcohol. Another study found that the level of womens control did not differ according to whether the transfer was in cash or food, but expenditure on alcohol was lower where women had most control. The issue appears to be country, culture and context specific. Experiences from the field: The Afghanistan PRRO evaluation stated that women preferred their husbands to do food for work instead of cash for work because the wives had more control over food than they did over cash. According to the Real Time Evaluation of WFPs response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami carried out

8

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

in early 2005, women in Sri Lanka preferred food, since cash was more likely to be used by men for other purposes, such as the purchase of alcohol and tobacco. This concern was raised by the Ministry of Social Welfare and Womens Affairs and was said to be confirmed in an earlier study financed by WFP. While women were responsible for food aid coupons, male family members were given control of cash coupons. The evaluation report also noted that, while women in both Indonesia and Sri Lanka were generally responsible for food and actually received the food aid directly, other types of support to livelihoods, such as boats, work tools and equipment and opportunities for cash for work, and/or cash distributions, were generally offered only to men13. An Ethiopia field case study for the Joint Evaluation of the Enabling Development policy of WFP notes that some women interviewed felt more secure receiving food of a fixed quantity, not being sure how much market prices might change if given cash, although one woman interviewed felt she could buy more of the local staple, sorghum, if given cash to buy on the local market, rather than wheat. The Enabling Development evaluation was supported by seven country case studies14 and made a general conclusion that food aid was appreciated by beneficiaries on the whole, with a large majority preferring it to cash transfers in Bolivia, Ethiopia, Mali and Mozambique. In Pakistan, women considered that they had better control over food coupons than over hard cash. On the other hand, the full report of the evaluation of the Sudan/Darfur emergency operation argued that the gender concerns about cash transfers (i.e. that they might be used less

13

responsibly than other transfers, might be appropriated by men etc) were not supported by the latest research and made reference to Harvey/ODI, 2005 and 2006 in this respect. The author observed, however, that the body of evidence on cash transfers in developing countries was still relatively limited. The End of Term Evaluation of WFPs Gender Policy for the period 2003-2007, undertaken in 2007-08, was concerned that more research and analysis should be done of the question of potential gender-based violence over the use of cash15. Other sources: A presentation at the Addis Ababa Technical Meeting on the Malawi caseload observed that joint decision making by men and women favoured the purchase of food in most cases and that female heads of households also prioritized food, whereas men did not. The Addis Ababa meeting report noted that experience gained by governments, NGOs and other actors in implementing and evaluating cash transfers showed that cash was overwhelmingly spent on food (50-60%). Related to this finding, however, was that empirical evidence on the nutritional impact of cash transfers was relatively scarce. More research is needed on nutritional impacts when food is replaced by cash transfers. One study16 presented at the Addis Ababa meeting found that per capita calorie intake in cash households was some 246 calories lower than the calorie intake of households receiving food. This would be just over ten percent of recommended daily calorie intake. Care would need to be taken in extrapolating these findings from one country, however. The WFP Cash and Food Transfers Primer lists gender as an important consideration in the food-cash debate, while noting that cultural habits regarding the management of cash resources make women more likely to prefer food transfers in many instances.

15

According to the Oxfam/WFP Evaluation of Processes undertaken for food and cash distributions in the Sri Lanka WFP cash transfer pilot project, however, there was no evidence to support the concern that cash transfers would be commandeered by men and expenditures diverted to social bads such as increased alcohol consumption. 14 The seven country case studies were: Bangladesh, Bolivia, Ethiopia, Honduras, Mali, Mozambique and Pakistan.

An earlier WFP evaluation of emergency operations in the Sudan (2004) had noted post-distribution gender violence as being a problem in southern Sudan following food distributions, so the problem is not specific to cash. 16 Sri Lanka Cash Transfer Pilot Project Highlight of Evaluation Results Powerpoint presentation.

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

Lesson 8: More field research is needed on the relative efficiency of food and cash transfers.

Summary: A couple of recent WFP Office of Evaluation reports quote secondary sources that cash transfers may be more efficient than food aid. More primary research needs to be done by WFP with partners, based on field case studies Experiences from the field: In the evaluation of Sudan/Darfur emergency operation 10339.0/1, the team leader refers to a recent OECD study (Clay, Riley, Urey & OECD, 2006, page 60), which looked at general food aid and relief food. The authors of this study concluded that, globally, food aid generally cost 30% more than similar commercial imports would have done. The implication seems to be that, all things being equal, if recipients had been given cash instead of in-kind imported food, they could have purchased 30% more with the cash on the commercial market. However, these are global findings and not directly relevant to the Darfur context, as local markets were not able to cope with the volume of food needed by the displaced populations . If WFP had delivered less food the price of food would have been far higher. Also, some donors may put a higher than commercial value on their in-kind food aid donations, for a variety of domestic reasons. Were they to give cash instead, it is not sure that they would provide the equivalent value in cash. Finally, WFP currently purchases a large percentage of its food aid on regional and local markets in developing countries. In such cases, the delivered cost should be compared to cost of commercially imported foodstuffs. Given the relatively recent introduction of cash interventions and their generally pilot nature, more comparative research needs to be done on the relative efficiency of food and cash interventions, particularly in the field. Other sources: The WFP Cash and Food Transfers Primer notes that almost all comparative studies show that when conditions are in place for cash delivery, transferring cash is less costly than distributing food, given the logistics and physical nature of the latter. To be kept in mind, however, is that food aid costs are often driven up by the urgency of actions to fix desperate humanitarian situations17.

17

See section 3.3 on page 12 of the Primer, on Cost effectiveness and efficiency.

Lesson 9: Pastoralists may take public works employment more seriously when paid in cash.

Summary: For a range of social reasons, pastoralists may take public works employment more seriously when paid with cash rather than food. Food payments are perceived more as charitable hand outs, while cash payments are seen as contractually binding Experiences from the field: The evidence base for this lesson is limited and comes from the full report of the evaluation of Ethiopia PRRO 10362.0 Enabling Livelihood Protection and Promotion. For a range of social reasons, it seems that pastoralists may take public works more seriously when paid with cash rather than with food. Food payments are perceived as being more as unconditional and charitable hand outs while cash payments are seen more as contractually binding transfers. Furthermore, as cash is also considered to be private property that need not be immediately shared out, workers are more motivated to do a good job. District Administrators thus found it harder to achieve any sort of quality control when payments were

10

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

made with food. The report does not give the basis for this statement (e.g. research or studies that might have been undertaken) and it is assumed that it is based on the observations of

local authorities, WFP field monitors and others. Also, the report does not indicate if the problem of quality control of public works applies when other, non-pastoralist, workers are employed.

Lesson10: Emergency Needs Assessments (ENAs) need to be clearer on follow-up responsibilities when cash interventions are recommended.

Summary: Some WFP Emergency Needs Assessment teams recommend cash interventions but are not specific about who should be responsible for follow-up. This is crucial, especially as many of the possible alternatives remain under government control.

Experiences from the field: The evidence for this lesson comes from the Evaluation of the WFP Strengthening Emergency Needs Assessment Implementation Plan undertaken in 2007. The evaluation team concluded that where ENAs do deliver usable non-food recommendations responsibility for action is often unclear, followup poor and recommendations are often ignored. For example, when assessments have recommended cash distributions the follow-up has generally been limited to NGOs at a very local level. The ability, or desire, of governments to take responsibility is a crucial dimension, especially as so many of the possible alternative intervention instruments remain uniquely under their control.

Other sources: The WFP Policy paper notes that interest and practice in the use of vouchers and cash transfers has grown exponentially in recent years, with part of the interest having been generated by WFPs progress in needs and market assessments, which are now based on broader food security analyses, as opposed to narrower food aid needs assessments. They often include recommendations on non-food transfer instruments as appropriate. For instance, the use of vouchers and/or cash transfers was recommended in about one-third of the 115 needs assessments conducted in 2006-2008.18

18

See paragraph 12 of the WFP Policy document.

11

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

Evaluation reports reviewed19

Thematic Full report of the evaluation of the end-of-term evaluation of WFPs Gender Policy (2003-2007) Enhanced Commitments to Women to Ensure Food Security; OEDE/2008/4. Evaluation of the WFP Strengthening Emergency Needs Assessment Implementation Plan, 2007; OEDE/2007/09. Thematic review of targeting in WFP relief operations, 2005; OEDE/2006/1. Joint evaluation (non-OEDE)20 of the Enabling Development policy of WFP, 2004-05. Regional Full report of the evaluation of Southern Africa regional PRRO 10310.0 mid-term evaluation, 2006; OEDE/2007/05. Full report of the real-time evaluation of WFPs response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami, February-May 2005; OEDE/2005/3. Country programmes Ethiopia Country Programme mid-term evaluation, June 2001; OEDE/2002/07. India Country Programme mid-term evaluation, 2006; OEDE/2007/1. Rwanda portfolio evaluation, April/May 2004; OEDE/2004/3. Protracted relief and recovery operations Full report of the evaluation of Somalia PRRO 6073.00 evaluation, July 2001; OEDE/2002/04. Full report of the evaluation of Afghanistan PRRO 10233 evaluation, April 2004; OEDE/2005/1. Full report of the evaluation of Tajikistan PRRO 10231.0 evaluation, 2006; OEDE/2006/11. Full report of the evaluation of Indonesia PRRO 10069 evaluation, 2006; OEDE/2007/04. Full report of the evaluation of Ethiopia PRRO 10362.0 evaluation; OEDE/2007/008. Full report of the evaluation of Madagascar PRRO 10442.0 evaluation, 2008; OEDE/2009/01. Emergency operations Full report of the evaluation of EMOP Sudan 10339.0/1 evaluation Assistance to populations affected by conflict in greater Darfur, West Sudan, 2006; OEDE/2007/002. Relief portfolios Full report of the evaluation of East Timor relief operations evaluation, January/February 2001; OEDE/2001/12. Full report of the evaluation of Angola Relief and Recovery Operations evaluation, 2005; OEDE/2005/4.

19 20

All reports are available at www.wfp.org/about/evaluation/list. The Director of the WFP Office of Evaluation served on the steering committee for this evaluation, however. The evaluation was organized by a group of interested donors.

12

Evaluation Top 10 Lessons - Cash and Vouchers, September 2009

Acronyms

EMOP Emergency Operation ENA Emergency Needs Assessment ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross IFPRI International Food Policy Research Institute IFRC International Federation of Red Cross NGO Non-Governmental Organization OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development PRRO Protracted Relief and Recovery Operation PSNP Productive Safety Net Programme UNHCR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

13

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- ERP Flow Chart GeneralDocument5 pagesERP Flow Chart Generalhendro irwansyahNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Potential WFP G2P Partner Programs in IndonesiaDocument34 pagesAssessment of Potential WFP G2P Partner Programs in IndonesiaJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Gender Equality and Food Security: Women's Empowerment As A Tool Against HungerDocument114 pagesGender Equality and Food Security: Women's Empowerment As A Tool Against HungerJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Hazard Map Myebon Kyaukphyu Ramrees Flood Area 03 Aug 2015 JPJXDocument1 pageHazard Map Myebon Kyaukphyu Ramrees Flood Area 03 Aug 2015 JPJXJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Myanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Document1 pageMyanmar Flood Inundated Area in Kale Townships Sagaing Region 29 Jul 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP Uganda and Burkina Faso's Trial To Reduce Post-Harvest Losses For Smallholder FarmersDocument4 pagesWFP Uganda and Burkina Faso's Trial To Reduce Post-Harvest Losses For Smallholder FarmersJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Typhoon Haiyan Damage Summary Manila Philippines, Global Agriculture Information Netowrk (GAIN), USDA/FAS, Dec 4, 2013Document3 pagesTyphoon Haiyan Damage Summary Manila Philippines, Global Agriculture Information Netowrk (GAIN), USDA/FAS, Dec 4, 2013Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Vanuatu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report #5 23 Mar 2015Document2 pagesVanuatu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report #5 23 Mar 2015Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP Kenya's Transitional Cash Transfers To Schools (TCTS) : A Cash-Based Home Grown School Meals ProgrammeDocument4 pagesWFP Kenya's Transitional Cash Transfers To Schools (TCTS) : A Cash-Based Home Grown School Meals ProgrammeJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP 2012 Update of Safety Nets Policy - The Role of Food Assistance in Social ProtectionDocument29 pagesWFP 2012 Update of Safety Nets Policy - The Role of Food Assistance in Social ProtectionJeffrey Marzilli100% (1)

- UNHCR 2009 Policy On Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban AreasDocument30 pagesUNHCR 2009 Policy On Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban AreasJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Setting The Right Priorities Protecting Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Afghanistan - Watchlist 2010Document60 pagesSetting The Right Priorities Protecting Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Afghanistan - Watchlist 2010Jeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- UNICEF Report: The Out-of-School Children of Sierra LeoneDocument77 pagesUNICEF Report: The Out-of-School Children of Sierra LeoneJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- WFP Oxfam Gaza Cash Voucher Programme ReviewDocument54 pagesWFP Oxfam Gaza Cash Voucher Programme ReviewJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Forced Migration Review, Issue 34: Adapting To Urban DisplacementDocument76 pagesForced Migration Review, Issue 34: Adapting To Urban DisplacementUrban Food SecurityNo ratings yet

- WB Targeting Assessment of Cash Transfer Program in Gaza and West BankDocument23 pagesWB Targeting Assessment of Cash Transfer Program in Gaza and West BankJeffrey MarzilliNo ratings yet

- Fill in The Gaps With A An The or Zero ArticleDocument3 pagesFill in The Gaps With A An The or Zero Articlekamolpan@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- IPENZ PN19-SeismicResistancePressureEquipmentFinalDocument138 pagesIPENZ PN19-SeismicResistancePressureEquipmentFinalnikhil0104No ratings yet

- Kijko & Graham - Pageoph, 1998 - Parametric-Historic PSHA Procedure I PDFDocument31 pagesKijko & Graham - Pageoph, 1998 - Parametric-Historic PSHA Procedure I PDFCamilo LilloNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law Cases DigestDocument32 pagesTransportation Law Cases DigestAngelo Igharas InfanteNo ratings yet

- Possible Failure Point Emerges in Miami-Area Building Collapse - The New York TimesDocument5 pagesPossible Failure Point Emerges in Miami-Area Building Collapse - The New York TimesMrMasterNo ratings yet

- Dhs Bib - Web Version - Final 508Document112 pagesDhs Bib - Web Version - Final 508jasonjasonNo ratings yet

- Caoch SWOT AnalysisDocument5 pagesCaoch SWOT Analysisyantao318No ratings yet

- KR CC: I MPA-018 I Master of Arts (Public Administration) Term-End Examination June, 2018 Mpa-018: Disaster ManagementDocument4 pagesKR CC: I MPA-018 I Master of Arts (Public Administration) Term-End Examination June, 2018 Mpa-018: Disaster ManagementAnushka SinghNo ratings yet

- Landslide 2Document16 pagesLandslide 2Prince JoeNo ratings yet

- Maritime CommerceDocument40 pagesMaritime CommerceDodong LamelaNo ratings yet

- LEEA New Rigging ManualDocument106 pagesLEEA New Rigging ManualAkramKassisNo ratings yet

- Emergency Response and Disaster Management Plan (Erdmp)Document25 pagesEmergency Response and Disaster Management Plan (Erdmp)Dinesh KanukolluNo ratings yet

- Calculate Earthquake Forces On Buildings and StructuresDocument5 pagesCalculate Earthquake Forces On Buildings and StructuresMelvin EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Climatechange ThesisDocument46 pagesClimatechange ThesisMinaNo ratings yet

- ADMS SimulationDocument2 pagesADMS Simulationacbien2No ratings yet

- Fire Incident at AMRI Hospital Kolkata PDFDocument5 pagesFire Incident at AMRI Hospital Kolkata PDFvikaspisalNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 Module 4 Understanding TyphoonDocument2 pagesQuarter 2 Module 4 Understanding Typhoonperrypetersonramos38No ratings yet

- Supervisory Policy Manual: TM-G-2 Business Continuity PlanningDocument19 pagesSupervisory Policy Manual: TM-G-2 Business Continuity PlanningYYY CCCNo ratings yet

- TragedyDocument3 pagesTragedySONANo ratings yet

- Đề 3Document7 pagesĐề 3Nguyễn VyNo ratings yet

- Transportation LawDocument61 pagesTransportation LawHelena Herrera100% (2)

- Climate of MumbaiDocument3 pagesClimate of MumbaiSheila J LowryNo ratings yet

- Eng21 (Story of Hamguchi Gohei)Document9 pagesEng21 (Story of Hamguchi Gohei)Alapan NandaNo ratings yet

- Weather TerminologiesDocument7 pagesWeather TerminologiesJ CNo ratings yet

- Tragedy & Common ManDocument3 pagesTragedy & Common ManbiffbiffordNo ratings yet

- Aycock - Shakespeare, Boito and VerdiDocument18 pagesAycock - Shakespeare, Boito and VerdiOlga SofiaNo ratings yet

- Accident QuizDocument15 pagesAccident QuizmujayanahNo ratings yet

- Sitxwhs003 Learner Guide v1.2 AcotDocument90 pagesSitxwhs003 Learner Guide v1.2 AcotKomal SharmaNo ratings yet

- VolcanoDocument59 pagesVolcanoJhanna Mae HicanaNo ratings yet