Professional Documents

Culture Documents

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

225 views(Cahiers Du Cinema Vol. 3) Nick Browne (Ed.) - 1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

(Cahiers Du Cinema Vol. 3) Nick Browne (Ed.) - 1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

Uploaded by

dimodimoRecommended to any film student or professional.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- CC 658Document30 pagesCC 658NSNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Role Interpretation in Nigerian Film Industry: A Study of Billionaires, Living in Bondage: Breaking FreeDocument23 pagesRole Interpretation in Nigerian Film Industry: A Study of Billionaires, Living in Bondage: Breaking Freeanon_453956231No ratings yet

- Development of Film Lighting in Modern CinematographyDocument31 pagesDevelopment of Film Lighting in Modern CinematographydimodimoNo ratings yet

- Jean Epstein Critical EssaysDocument440 pagesJean Epstein Critical EssaysEileen LeahyNo ratings yet

- Carolyn Jess Cooke - Film Sequels Theory and Practice From Hollywood To BollywoodDocument177 pagesCarolyn Jess Cooke - Film Sequels Theory and Practice From Hollywood To BollywoodJimmy NewlinNo ratings yet

- 2013 Opel Meriva 101433Document231 pages2013 Opel Meriva 101433dimodimoNo ratings yet

- Instruction Manual Mount Change Instructions Zeiss Cinema Zoom LensesDocument24 pagesInstruction Manual Mount Change Instructions Zeiss Cinema Zoom LensesdimodimoNo ratings yet

- Truth and Symbol Karl Jaspers Twayne 1959Document96 pagesTruth and Symbol Karl Jaspers Twayne 1959dimodimoNo ratings yet

- Krzysztof Kieslowski - I'm So-SoDocument149 pagesKrzysztof Kieslowski - I'm So-SodimodimoNo ratings yet

- The Films of Federico FelliniDocument27 pagesThe Films of Federico Fellinidimodimo100% (1)

- Barry K. Grant - American Cinema of The 1960s, Themes and Variations (2008)Document297 pagesBarry K. Grant - American Cinema of The 1960s, Themes and Variations (2008)Kornelia Piekut100% (7)

- Screenplay - जामुन का पेड़Document5 pagesScreenplay - जामुन का पेड़RAHUL HEERADASNo ratings yet

- Final Result EPFO Stenographer (Group C) ExaminatDocument2 pagesFinal Result EPFO Stenographer (Group C) Examinatmail mailucNo ratings yet

- Speaking Club CinemaDocument5 pagesSpeaking Club CinemaOlhaNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Cause ListDocument337 pagesConsolidated Cause ListJitendra SinghNo ratings yet

- Wa0031.Document56 pagesWa0031.dudelal09No ratings yet

- BreathlessDocument7 pagesBreathlessforcinema97No ratings yet

- Kelas 6 Arivu Senarai NamaDocument3 pagesKelas 6 Arivu Senarai NamasumithraNo ratings yet

- UPPSC JE 2013 Final ResultDocument28 pagesUPPSC JE 2013 Final ResultAnshika RanaNo ratings yet

- Hayao Miyazaki: Tips For Creating Ghibli Like StoriesDocument1 pageHayao Miyazaki: Tips For Creating Ghibli Like StoriesFernando VelázquezNo ratings yet

- Nellore DataDocument64 pagesNellore DataDIKSHA VERMA50% (2)

- Laporan Hasil UjianDocument2 pagesLaporan Hasil UjianrafiqahheryasNo ratings yet

- Changes in Our LivesDocument10 pagesChanges in Our LivesAndreaNo ratings yet

- Out of Time Desire in Atemporal Cinema TDocument19 pagesOut of Time Desire in Atemporal Cinema TLed Media PlusNo ratings yet

- Ponette: Jacques DoillonDocument2 pagesPonette: Jacques DoillonGaspabzNo ratings yet

- Reading Practice 3Document5 pagesReading Practice 3Bé HàNo ratings yet

- Provisional Select ListDocument3 pagesProvisional Select ListKailash NathNo ratings yet

- Geraghty. A Tuberous Fetish. The Potato As Protagonist in Claudia Llosa's La Teta Asustada (2009)Document30 pagesGeraghty. A Tuberous Fetish. The Potato As Protagonist in Claudia Llosa's La Teta Asustada (2009)etronevichNo ratings yet

- Tum Haseen Main JawaanDocument3 pagesTum Haseen Main Jawaanrishisap2No ratings yet

- 28 Legacy B1 - 1 Test 8BDocument5 pages28 Legacy B1 - 1 Test 8BДрийми ООДNo ratings yet

- (123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDocument23 pages(123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDwayne HarrisonNo ratings yet

- William Shakespeare - Hamlet, Antony and Cleopatra, King Lear, Othello and MacbethDocument760 pagesWilliam Shakespeare - Hamlet, Antony and Cleopatra, King Lear, Othello and MacbethQuilcueNo ratings yet

- Gold Preliminary Unit 8 Test: 1 Complete The Sentences With An Adjective Made From The Word in BracketsDocument2 pagesGold Preliminary Unit 8 Test: 1 Complete The Sentences With An Adjective Made From The Word in Bracketseuge pasNo ratings yet

- 9a The Tallgrass Film FestivalDocument31 pages9a The Tallgrass Film FestivalSilvia Tiara Budi HastutiNo ratings yet

- DIPSEV - 01 Dec 2022 - To - 31 Dec 2022Document200 pagesDIPSEV - 01 Dec 2022 - To - 31 Dec 2022BalaNo ratings yet

- EA ResultDocument32 pagesEA ResultGovind GautamNo ratings yet

- CCNA in InternetDocument13 pagesCCNA in InternetBiswajit SahooNo ratings yet

- Atestat de Competenţ Lingvistic Limba Englez : Colegiul Naţional Nicolae B Lcescu"Document17 pagesAtestat de Competenţ Lingvistic Limba Englez : Colegiul Naţional Nicolae B Lcescu"ClaudiaGhetuNo ratings yet

(Cahiers Du Cinema Vol. 3) Nick Browne (Ed.) - 1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

(Cahiers Du Cinema Vol. 3) Nick Browne (Ed.) - 1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

Uploaded by

dimodimo100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

225 views361 pagesRecommended to any film student or professional.

Original Title

[Cahiers Du Cinema Vol. 3] Nick Browne (Ed.) - 1969-1972 ~ the Politics of Representation

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRecommended to any film student or professional.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

225 views361 pages(Cahiers Du Cinema Vol. 3) Nick Browne (Ed.) - 1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

(Cahiers Du Cinema Vol. 3) Nick Browne (Ed.) - 1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

Uploaded by

dimodimoRecommended to any film student or professional.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 361

Cahiers

du

Cinema

Cahiers

du

. rT

Cinéma

Volume 3

1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

An anthology from Cahiers du Cinéma nos 210-239,

March 1969-June 1972

Edited by

Nick Browne

2891 Cahiers du Cinema Vol III

First published 1990

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

Reprinted in 1996

Original French articles © Les Editions de I Etoile 1969-72

English translations and editorial matter

© The British Film Institute 1990

Phototypeset in 10/11'/ Linotron Palatino by Input Typesetting Ltd, London

Printed in Great Britain by

Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Alll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic,

mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented,

including photocopying and recording, or in any information

storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing

‘from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Cahiers du cinéma.

Vol. 3: 1969-1972: The politics of representation

1. Cinema films, 1950-1985 — Critical studies

L. Brown, Nick

791.4310904

ISBN 0-415-02987-2

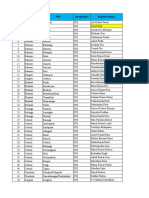

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The Politics of Representation: Cahiers du Cinéma 1969-72

1. Jean Narboni, Sylvie Pierre, Jacques Rivette: ‘Montage’ (March

69)

2. Jean-Pierre Qudart: ‘Cinema and Suture’ (April-May 1969)

3. Jean-Louis Comolli, Jean Narboni: ‘Cinema/ldeology/Criticism’

(October 1969)

4 Pascal Bonitzer, Jean-Louis Comolli, Serge Daney, Jean Narboni,

Jean-Pierre Oudart: ‘Le Vie est @ nous: A militant film’, (March

5. Jean-Pierre Oudart, Jean Narboni, Jean-Louis Comolli: ‘Readings

of Jancs6: Yesterday and Today’ (April 1970)

Editorial: ‘Russia in the 20s (I (May-June 1970)

Serge Daney, Jean-Pierre Oudart: ‘Work, Reading, Pleasure’

Guly 1970)

8 Jean-Pierre Oudart: Word Play, Master Play’ (August-September

70)

9 Editorial: ‘Japanese Cinema (1)’ (October 1970)

10 Jean Narboni: ‘Vicarious Power’ (October 1970)

11 Jean-Louis Comolli: ‘Film/Politics (2): L’Aveu: 15 Propositions’

(October 1970)

12 Collective text: ‘Josef von Sternberg’s Morocco’ (November-

December 1970)

13. Collective Editorial Statement (Cahiers du Cinéma, Cinéthique, Tel

Quel): ‘Cinema, Literature, Politics’ (January-February 1971)

14 Jean-Pierre Oudart: The Reality Effect’ (March-April 1971)

15_ Jean-Pierre Oudart: ‘Notes for a Theory of Representation’ (May-

June and July 1971)

vii

21

45

58

68

89

112

115

137

146

150

163

174

187

189

203

Contents

16 Jean-Louis Comolli: ‘Technique and Ideology: Camera, Perspec-

tive, Depth of Field’ (May-June and July 1971)

17. Pascal Bonitzer: ’ “Reality” of Denotation’ (May-June 1971)

18 Jacques Aumont, Pascal Bonitzer, Jean Narboni, Jean-Pierre

‘Oudart: ‘The New Babylon: the “Commune” Metaphor’ (July and

October 1971)

19. Jean-Pierre Oudart: ‘A Lacking Discourse’ (October 1971)

20 Cahiers du Cinéma: ‘Cinema, Ideology, Politics (for Poretta-

Terme)’ (October 1971)

21. Pascal Bonitzer: ‘Off-screen Space’ (December 1971-January-Feb-

ruary 1972)

22. Serge Daney, Jean-Pierre Oudart: ‘The Name of the Author (on

the “place” of Death in Venice)’ (December 1971-January-February

1972)

23 Pascal Kané: ‘Re-reading Hollywood Cinema: Sylvia Scarlett’

(May-June 1972)

24 Editorial: ‘Politics and Ideological Class Struggle’ (December

1971-January-February 1972)

Appendix 1

Guide to Cahiers du Cinéma Nos 210-39, March 1969-June 1972, in

English translation

Appendix 2

Cahiers du Cinéma in the 1950s, the 1960s and the later 1970s

Index of Names and Film Titles

vi

213

248

254

276

287

291

306

325

334

342

345

349

Preface

The project for an anthology of writing from Cahiers du Cinéma in the

immediate post-1968 period arose in response to the changing place of

film in American culture in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and to the

transformative effect of French film theory on film study in America. The

project came together in 1976, when with the encouragement of Professor

Stanley Cavell and the Harvard University Press, an agreement to proceed

was reached with Serge Daney, then Editor-in-Chief of Cahiers. Sub-

sequently, with the decision of the British Film Institute to undertake a

multi-volume anthology covering the history of Cahiers, this volume was

incorporated in that series.

Volume 3 has been carried out in full agreement with Jim Hillier’s

general statement of policy for the series in his Preface to the first two

volumes: ‘that each volume should be self-contained and coherent in its

own terms, should seek to be representative of the period covered, should

contain largely material not readily available before in English translation,

should be relevant to contemporary film education and film culture,

should be accessible to the non-specialist reader, and should be pleasur-

able.’ The materials contained in this volume may be different from Vol-

umes 1 and 2 in their accessibility and their conditions of pleasure. In this

period Cahiers sought explicitly to integrate the post-structuralist perspec-

tives of the wider French cultural and intellectual scene, intermixing narra-

tology, grammatology, semiotics, Marxism, and psychoanalysis, Thus a

number of these texts are ‘difficult’.

The introductory essay undertakes to situate this work within the gen-

eral intellectual scene, to analyse the Cahiers project, and thus to make it

more available. The material is presented chronologically, Overall, the

aims of the volume are: first, to present essential materials for a historical

reconstruction of the intellectual dynamic of the period; and second, to

gatige Cahiers’ contribution to the formation of contemporary film theory.

Preface

A note on translations

Translation always poses problems about accurate rendition, especially

when, as in this case, several different translators are involved and when

the original writing is difficult. It would be wrong to pretend that we have

not experienced occasionally quite severe problems of translation. There

are a number of points where we have had difficulty in grasping the

precise sense of the original and others where, despite such a grasp, the

right translation has been difficult to find.

The French terms auteur and mise en scene have entered critical discussion

in English, but auteur in particular did not always have some of the

meanings currently attached to it. We have usually retained auteur when,

‘author’ would have been a direct translation and mise en scine where

‘direction’ might have been a suitable rendering, but we have tried to be

sensitive to the varying usage of the terms. The same principle has been,

applied to such theoretical terms as écriture for which there is no adequate

translation.

Les Cahiers du Cinéma (literally ‘Cinema Notebooks’) are plural, but we

have preferred to refer to Cahiers - the normal abbreviation used — as if in

the singular.

Notes

All notes are the editor’s except where specifically designated as authors’

or translators’ notes.

viii

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Cahiers du Cinéma for the agreement to produce these

volumes of anthology from their material.

In addition, the editor and publishers acknowledge permission to reprint

the following material:

Chapter 1, translated by Tom Milne, is reprinted from Rivette: Texts and

Interviews, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum (© British Film Institute, 1977)

Chapter 2, translated by Kari Hanet (with contributions by Henry Segg-

exman), is reprinted from Screen, vol. 18, no. 4 (© The Society for Edu-

cation in Film and Television, 1977).

Chapter 3, translated by Susan Bennett, is reprinted from Screen, vol.

12, no. 1 © The Society for Education in Film and Television, 1977).

Chapter 12, translated by Diana Matias, is reprinted frost’ Sternberg,

edited by Peter Baxter (© British Film Institute, 1980).

1 take pleasure in acknowledging the co-operation of Serge Daney of

Cahiers du Cinéma, Maud Wilcox of the Harvard University Press, and the

editors at the British Film Institute - Angela Martin and David Wilson -

who did extraordinarily conscientious work on both the translation and

the manuscript. I thank in particular the original group which undertook

translation: Henry Seggerman, Lindley Hanlon, Randall Conrad, Leigh

Hafrey, Joseph Karmel, Alan Williams, Nancy Kline Piore; and the BFI

translators Diana Matias and Annwyl Williams.

Routledge and the British Film Institute gratefully acknowledge the help

of Cahiers du Cinéma in the compilation of these volumes.

Introduction: The Politics of

Representation: Cahiers du

Cinéma 1969-72

What is dramatized in this collection of texts from the 1969-72 period of

Cahiers du Cinéma is the spectacular action of rigorous and politically

engaged film criticism. Cahiers’ central project was to elaborate a method

of, or a critical perspective on, filmic ‘writing’ considered in its social

relations, By means of a form of critical ‘reading’, Cahiers sought to analyse

and to transform the relation between film-texts and the ideology of the

culture in which they are viewed.

In the context of the radically charged social and intellectual movements

of post-1968 France, Cahiers du Cinéma was at work transforming both the

perception of films and critical writing about cinema. Cahiers set about

clarifying its historical and polemical co-ordinates by reference to Bazin

and Eisenstein, and self-consciously began the process of shaping the

passage from the old to the new socio-filmic order by the force of its

critical intervention. Its resolutely Marxist denunciation of the function

and effect of bourgeois ideology was projected as the critique and rewriting

of film history/theory/criticism.

The experience of change in post-1968 France marks these texts in

multiple ways. Change is pictured as an opened theoretical space, the

space of representation. History assumes the aspect of an ensemble of

unevenly developed, stratified and shifting relations enacted in a new

social setting. Old connections are broken or displaced; new structures

and commitments are in the process of emerging. The sense of uneven,

fragmented movement of diverse but associated themes makes the ensem-

ble of these texts an unfinished work site. In this context, montage is

pictured as an exemplary mode of critical work. Through its procedures

of writing it rearranges significant relations, transforms pre-texts (the cul-

turally and normally invested fields of fixed senses), interrupts and

renegotiates notions of liaison and continuity. Its deconstructive form of,

productivity is the result of both action and negation.

Cahiers’ intervention within this cultural setting of change and mutation

1

1969-1972 The Politics of Representation

takes the dialectical form of a writing project — arbitrating between old

and new, structure and history. It challenges the presuppositions about

the relation of film theory to the social order by affirming the centrality

of the dialectic between ideology and representation. Cahiers joins the

struggle on this front: its principal interlocutor and antagonist is the figure

of dominant ideology as instituted by the bourgeois apparatus of cinema.

Cahiers undertakes by its writing to disqualify the institution of Classic

Representation and to create a new and transformed social space. The

discourse of film theory and criticism that effects this passage from old to

new is at the same time drama (spectacle), argument (exposition), dialectic

(movement, determination, spacing, ultimately history) and action (inter

vention for political change).

Notwithstanding the sense of a project still in motion, a project collec-

tively developed through the organization of several voices, the Cahiers

materials assembled here have a structure and an argument. As a monthly

review, its theories and positions were elaborated and modified, even

deflected, over the course of publication. Its form of cohesion is historical,

The unity, such as it is, of the Cahiers project is defined through the

question of how social life is represented at the ideological level. The object

of the project is the critique and transformation of society's ideological

superstructure in so far as it is supported by cinema. The questions that

Cahiers puts to cinema and that define film theory/criticism are finally

treated as political questions - of power, class struggle, and theoretical

practice. As a text, this collection of Cahiers writings is composed by the

integration and displacement of key terms, each embedded in a context:

‘writing’, ‘reading’, ‘ideology’, ‘subject’, ‘history’. In so far as its perspec-

tive is the transformation of existing structures, the Cahiers project is

defined as a politics, not a poetics, of representation,

The materials presented here are basically from the period March 1969

to January 1972, This framework registers the force and effect of the

political events of May 1968 on the institution of cinema. Though a crisis

within Cahiers in November 1969 led to a change in ownership, during

the period which this volume principally covers (October 1969 to February

1972) the Editorial Board, directed by Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Nar-

boni, remained virtually unchanged. This phase concluded, more or less,

in January 1972 with the open break with the French Communist Party,

and an alignment with Maoism. Shortly afterwards, the format of the

review changed, declaring a reorientation towards its public.

Cahiers’ engagement in the central cultural politics of the time, and its

commitment to a cultural line founded on dialectical materialism, is

reflected in its various relations ~ attack, defence, and affiliation - to

the intellectual scene. Reconstruction of the form and significance of its

intervention as film theory must in fact take into account Cahiers’ relation

to other positions and other texts: historical precedents, rival critical prac

tices, contemporary supporters, its guiding texts. The break with the

critical past, represented, of course, by the ‘idealist’ tradition of André

2

Introduction: The Politics of Representation: Cahiers du Cinéma 1969-72

Bazin, prompts the retrieval of Eisenstein as a guiding reference. Eisenste-

in’s framework of dialectical materialism as the basis for aesthetic inquiry

serves to link Cahiers’ project with the revolutionary Russian intellectual

and artistic culture of the 1920s. The Eisenstein translation project con-

sisted of fifteen instalments (from February 1969 to January-February 1971)

and culminated in issues devoted to revolutionary Russian film culture

(May-June 1970) with texts by and commentary on Vertov, Lenin, Eis-

enstein, Mayakovsky, Meyerhold, Kuleshoy, etc., and a special Eisenstein

issue (January-February 1971). The Editorial Board’s ‘Russia in the Twent-

ies’ indicates the significance and aims of the overall project and shows

the way in which Cahiers sought to appropriate Eisenstein, and Russian

practice more generally, to the contemporary situation.

Within the post-1968 scene, Cahiers sought, by various means, to elabor-

ate and extend its position. The differences between Cahiers and Cingthique,

for example, were made explicit in its polemical ‘refutation’ of Cinéthique

published in November 1969. Cahiers shared with Cinéthique the view that

the social function of cinema is the reproduction of bourgeois ideology,

that film is disguised work product, that mode of address can constitute

a break with bourgeois norms, etc. But Cahiers rejected an aesthetics of

transgression, based on the self-reflexive practice of the avant-garde, and

developed, through painstaking analysis, its own account of the formal

terms of such a break.

Positif’s attack (no, 122, December 1970) on Cahiers, structuralism, and

the literary/cultural review Tel Quel was a broadside. An article attacked

Cahiers’ positive evaluation of Straub-Huillet’s Othon and denounced the

review as totalitarian, opportunist, Stalinist, elitist, a pretender to scientific

criticism. Cinéthique, Tel Quel, and Cahiers joined in a statement (‘Cinema,

literature, politics’, January-February 1971) denouncing Positif for a ‘para-

sitism’ that aimed to censor and deform a scientific Marxist-Leninism.

‘What seems to be at stake in these exchanges is the legitimacy and auth-

ority of Cahiers’ collective voice to assume and command centre stage, to

take a public position, and to speak for the truth of a scientific Marxist-

Leninist discourse in the field of film.

The overall aim of this volume is to present the material essential to

defining the ensemble of themes and positions that compose the history of

Cahiers during the 1969-72 period. The volume provides the fundamental

materials for a critical appreciation of the Cahiers position in contemporary

film theory and criticism. Even though Cahiers drew heavily on many

sources and fields which constituted the context of the Cahiers project

(including work by Burch, Barthes, Bellour, Metz, etc.), this ‘independent’

material is present only by implication or reference and is in most instances

available in translation elsewhere. We are publishing only primary

materials from Cahiers which are not readily available. Hence, the widely

reprinted text on Young Mr Lincoln (Cahiers 223, August-September 1970)

is not included here.

We are presenting this material in its scope and diversity, and in its

3

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- CC 658Document30 pagesCC 658NSNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Role Interpretation in Nigerian Film Industry: A Study of Billionaires, Living in Bondage: Breaking FreeDocument23 pagesRole Interpretation in Nigerian Film Industry: A Study of Billionaires, Living in Bondage: Breaking Freeanon_453956231No ratings yet

- Development of Film Lighting in Modern CinematographyDocument31 pagesDevelopment of Film Lighting in Modern CinematographydimodimoNo ratings yet

- Jean Epstein Critical EssaysDocument440 pagesJean Epstein Critical EssaysEileen LeahyNo ratings yet

- Carolyn Jess Cooke - Film Sequels Theory and Practice From Hollywood To BollywoodDocument177 pagesCarolyn Jess Cooke - Film Sequels Theory and Practice From Hollywood To BollywoodJimmy NewlinNo ratings yet

- 2013 Opel Meriva 101433Document231 pages2013 Opel Meriva 101433dimodimoNo ratings yet

- Instruction Manual Mount Change Instructions Zeiss Cinema Zoom LensesDocument24 pagesInstruction Manual Mount Change Instructions Zeiss Cinema Zoom LensesdimodimoNo ratings yet

- Truth and Symbol Karl Jaspers Twayne 1959Document96 pagesTruth and Symbol Karl Jaspers Twayne 1959dimodimoNo ratings yet

- Krzysztof Kieslowski - I'm So-SoDocument149 pagesKrzysztof Kieslowski - I'm So-SodimodimoNo ratings yet

- The Films of Federico FelliniDocument27 pagesThe Films of Federico Fellinidimodimo100% (1)

- Barry K. Grant - American Cinema of The 1960s, Themes and Variations (2008)Document297 pagesBarry K. Grant - American Cinema of The 1960s, Themes and Variations (2008)Kornelia Piekut100% (7)

- Screenplay - जामुन का पेड़Document5 pagesScreenplay - जामुन का पेड़RAHUL HEERADASNo ratings yet

- Final Result EPFO Stenographer (Group C) ExaminatDocument2 pagesFinal Result EPFO Stenographer (Group C) Examinatmail mailucNo ratings yet

- Speaking Club CinemaDocument5 pagesSpeaking Club CinemaOlhaNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Cause ListDocument337 pagesConsolidated Cause ListJitendra SinghNo ratings yet

- Wa0031.Document56 pagesWa0031.dudelal09No ratings yet

- BreathlessDocument7 pagesBreathlessforcinema97No ratings yet

- Kelas 6 Arivu Senarai NamaDocument3 pagesKelas 6 Arivu Senarai NamasumithraNo ratings yet

- UPPSC JE 2013 Final ResultDocument28 pagesUPPSC JE 2013 Final ResultAnshika RanaNo ratings yet

- Hayao Miyazaki: Tips For Creating Ghibli Like StoriesDocument1 pageHayao Miyazaki: Tips For Creating Ghibli Like StoriesFernando VelázquezNo ratings yet

- Nellore DataDocument64 pagesNellore DataDIKSHA VERMA50% (2)

- Laporan Hasil UjianDocument2 pagesLaporan Hasil UjianrafiqahheryasNo ratings yet

- Changes in Our LivesDocument10 pagesChanges in Our LivesAndreaNo ratings yet

- Out of Time Desire in Atemporal Cinema TDocument19 pagesOut of Time Desire in Atemporal Cinema TLed Media PlusNo ratings yet

- Ponette: Jacques DoillonDocument2 pagesPonette: Jacques DoillonGaspabzNo ratings yet

- Reading Practice 3Document5 pagesReading Practice 3Bé HàNo ratings yet

- Provisional Select ListDocument3 pagesProvisional Select ListKailash NathNo ratings yet

- Geraghty. A Tuberous Fetish. The Potato As Protagonist in Claudia Llosa's La Teta Asustada (2009)Document30 pagesGeraghty. A Tuberous Fetish. The Potato As Protagonist in Claudia Llosa's La Teta Asustada (2009)etronevichNo ratings yet

- Tum Haseen Main JawaanDocument3 pagesTum Haseen Main Jawaanrishisap2No ratings yet

- 28 Legacy B1 - 1 Test 8BDocument5 pages28 Legacy B1 - 1 Test 8BДрийми ООДNo ratings yet

- (123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDocument23 pages(123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDwayne HarrisonNo ratings yet

- William Shakespeare - Hamlet, Antony and Cleopatra, King Lear, Othello and MacbethDocument760 pagesWilliam Shakespeare - Hamlet, Antony and Cleopatra, King Lear, Othello and MacbethQuilcueNo ratings yet

- Gold Preliminary Unit 8 Test: 1 Complete The Sentences With An Adjective Made From The Word in BracketsDocument2 pagesGold Preliminary Unit 8 Test: 1 Complete The Sentences With An Adjective Made From The Word in Bracketseuge pasNo ratings yet

- 9a The Tallgrass Film FestivalDocument31 pages9a The Tallgrass Film FestivalSilvia Tiara Budi HastutiNo ratings yet

- DIPSEV - 01 Dec 2022 - To - 31 Dec 2022Document200 pagesDIPSEV - 01 Dec 2022 - To - 31 Dec 2022BalaNo ratings yet

- EA ResultDocument32 pagesEA ResultGovind GautamNo ratings yet

- CCNA in InternetDocument13 pagesCCNA in InternetBiswajit SahooNo ratings yet

- Atestat de Competenţ Lingvistic Limba Englez : Colegiul Naţional Nicolae B Lcescu"Document17 pagesAtestat de Competenţ Lingvistic Limba Englez : Colegiul Naţional Nicolae B Lcescu"ClaudiaGhetuNo ratings yet