Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Qualitative Perspectives

Qualitative Perspectives

Uploaded by

fiserada0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

46 views8 pagesCrowther

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCrowther

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

46 views8 pagesQualitative Perspectives

Qualitative Perspectives

Uploaded by

fiseradaCrowther

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 8

Supplement

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational

Research

Toni Tripp-Reimer, RN, PhD, FAAN, Bradley Doebbeling, MD, MS

ABSTRACT

The rapid uptake of qualitative approaches in translational research can be best understood in the

context of recent innovations in health services research, as well as an overarching concern with improving

the quality of health care. Qualitative approaches highlight the human dimension in health care by

foregrounding the perceptions, experiences, and behaviors of both consumers and providers of care.

As such, these methods are particularly useful for addressing the complex issues related to improving

health care quality and implementing system change. This overview traces a brief history of the factors

contributing to the recent and rapid growth of qualitative methods in health research in general and

translational research in particular; describes the varieties of qualitative approaches employed in this

research; and illustrates the utility of these approaches for variable identification, instrument development,

description/explanation of patient/provider perceptions and behaviors, individual/organizational change,

and theory refinement.

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2004; 1(S1):S65S72. Copyright 2004 Sigma Theta Tau International

KEYWORDS qualitative methods, naturalistic inquiry, qualitative synthesis, translational research, evidence-

based practice, patient experience, provider behavior, theory construction, Cochrane Qualitative Methods

Group

INTRODUCTION

W

hile qualitative approaches in research have

been increasingly recognized as providing

distinct and significant contributions in health research

for the past 40 years, they have received unprecedented

emphasis in the past 5 years. The rapid uptake of qualita-

tive approaches in translational research can be best under-

stood in the context of recent innovations in health services

research, as well as an overarching concern with improv-

ing the quality of health care. Qualitative approaches high-

light the human dimension in health care by foregrounding

Toni Tripp-Reimer, Professor and Associate Dean for Research, The University of Iowa,

College of Nursing, Bradley Doebbeling, General Internal Medicine Professorship in

Health Services Research, Indiana University School of Medicine; Associate Director for

Health Services Research, Regenstrief Institute for Health Care; Director, Health Services

Research Service (11-H), Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA.

Address correspondence to Toni Tripp-Reimer, Professor and Associate Dean for

Research, The Univercity of Iowa, College of Nursing, 50 Newton Road, Iowa City,

IA 52242, USA; toni-reimer@uiowa.edu

This article was presented at the U.S. Invitational Conference Advancing Quality

Care Through Translation Research, October 1314, 2003, at the University of

Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa.

Copyright 2004 Sigma Theta Tau International

1545-102X1/04

the perceptions, experiences, and behaviors of both con-

sumers and providers of care. As such, these methods are

particularly useful for addressing the complex issues re-

lated to improving health care quality and implementing

system change. Qualitative research offers a variety of

methods for identifying what really matters to patients and

[providers], detecting obstacles to changing performance,

and explaining why improvement does or does not occur

(Pope, vanRoyen&Baker 2002, p. 148). This overviewwill

trace a brief history of the factors contributing to the recent

and rapid growth of qualitative methods in health research

in general and translation research in particular; describe

the varieties of qualitative approaches employed in this re-

search; and illustrate the utility of these approaches for

variable identification, instrument development, descrip-

tion/explanation of patient/provider perceptions and be-

haviors, as well as individual/organizational change.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Qualitative approaches in translational research need to be

understood within the broader context of the recent uptake

of qualitative methods in health services research. Qualita-

tive approaches inhealth-related researchwere first used by

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

r

Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004 S65

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational Research

anthropologists conducting ethnographies in remote cul-

tures (Rivers 1924; Evans-Pritchard 1937). Later sociol-

ogists adapted observational techniques to study aspects

of the biomedical health system (Becker, Geer, Hughes &

Strauss 1961; Goffman 1961, 1963). Nursing was the first

health discipline to identify the importance of qualitative

methods, legitimize them, and incorporate them into re-

search. Over the past decade, and particularly in the past 5

years, there has been an exponential increase in the use of

qualitative approaches in health services and translational

research.

Federal, national, and international agencies and ini-

tiatives have facilitated this evolution through a variety

of mechanisms such as conferences and reports. Two fed-

eral funding agencies in the United Statesthe National

Institutes of Health (NIH) and Agency for Health Re-

search and Quality (AHRQ)have promoted qualitative

approaches througha series of developmental/training con-

ferences and calls for applications. In 1998, the Agency for

Health Care Policy and Research (now AHRQ) and The

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation co-sponsored a ground-

breaking conference titled Qualitative Methods in Health

Services Research in Rockville, Maryland, with 78 in-

vited participants from health services research and social

science (http://www.ahcpr.gov/about/cods/codsqual.htm).

These proceedings were subsequently published in the

journal Health Services Research (Devers, Sofaer & Rundall

1999). In1999, a workshop of social scientists organized by

the National Institute for Mental Health and the National

Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism resulted in the

guide Qualitative Methods in Health Research: Opportu-

nities and Considerations in Application and Review for

investigators using qualitative approaches http://obssr.od.

nih.gov/Publications/Qualitative.PDF. Shortly thereafter,

in 2002, NIH sponsored the conference Using Quali-

tative Methods to Promote Self-Care in Diverse Popu-

lations (http://obssr.od.nih.gov/Conf Wkshp/Adherence

/Qualitative Methods.htm). A final example is the 2004

NIH conference The Design and Conduct of Qualitative

and Mixed-Method Research sponsored by the Office of

the Director, Office of Behavioral and Social Science Re-

search (http://obssr.od.nih.gov/conf wkshp/sw/).

Publications in health literature reflect these develop-

ments. While nursing science journals have published

qualitative studies since the 1952 inaugural issue of Nurs-

ing Research, medical and health research journals have

only more recently incorporated such studies. In the

past decade, a series of editorials in prominent medi-

cal journals, particularly the British Journal of Medicine

and to a lesser extent the Journal of the American Medi-

cal Association, have highlighted the importance of qual-

itative approaches. Similarly, the National Institute of

Medicine issued a series of reports specifically calling

for increased use of qualitative approaches in health

research:

r

Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming

Health Care Quality (Adams & Corrigan 2003)

r

Leadership by Example: Coordinating Government

Roles in Improving Health Care Quality (Corrigan,

Eden & Smith 2002)

r

Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Pub-

lic Health Professionals for the 21st Century (Gebbie,

Rosenstock & Hernandez 2003)

r

Speaking of Health: Assessing Health Communica-

tion Strategies for Diverse Populations (Institute of

Medicine 2002)

r

Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic

Disparities in Health Care (Smedley, Stith & Nelson

2003)

r

Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for

the 21st Century (Institute of Medicine 2001)

r

Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social

and Behavioral Research (Smedley & Syme 2000)

The British-based International Cochrane Collabora-

tion prepares, maintains, and disseminates systematic re-

views. In 2001, the Qualitative Methods Group was of-

ficially registered as an active component of the overall

Cochrane Collaboration in partnership with the Camp-

bell Process Implementation Methods Group. The goals

of the Cochrane Qualitative Methods Group are to

(a) demonstrate the value of qualitative research through

systematic reviews, (b) disseminate methodological stan-

dards to aid the evaluation of qualitative research,

(c) promote the synthesis and integration of qualita-

tive research within the broader literature syntheses, and

(d) provide some training in qualitative methods syn-

thesis: (http://www.lancs.ac.uk/depts/ihr/research/public

/cochrane.htm).

This recent and rapidly increasing attention and activity

have been triggered by several sources including increasing

healthcare costs, increasing healthdisparities, unexplained

practice variation, the increased role of the consumer voice,

the complexity of clinical decision making, and the recog-

nition that practice changes are not driven solely by sci-

entific knowledge (Jones 1995; Popay, Rogers & Williams

1998; Shortell 1999; Pope, van Royen & Baker 2002). For

example, the recent, but dramatic, emergence of patient-

centered initiatives, such as the Picker/Commonwealth

Program for Patient-Centered Care approach, mandate at-

tention be given to topics such as respect for patient values,

preferences, and needs that are best identified and under-

stood through qualitative approaches.

Shortell (1999) views the growing role of qualitative ap-

proaches in translation research as reflecting the need for a

more in depth (sic) understanding of naturalistic settings,

S66 Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004

r

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational Research

the importance of understanding context, and the com-

plexity of implementing social change (p. 1083). Corre-

spondingly, the greater appreciation of qualitative methods

can be traced to the growing recognition that many health

problems and processes of care do not fit easily into exper-

imental research designs (Popay, Rogers & Williams 1998,

p. 341).

NATURE OF QUALITATIVE APPROACHES

While in a literal sense, qualitative methods include all

modes of inquiry that do not use statistical methods; the

term is actually a misnomer. The terms qualitative and

quantitative actually refer to forms of data, not to forms of

design. More accurately, qualitative and quantitative data

are generally collected through naturalistic and positivis-

tic designs, respectively. Further, both forms of data come

from empirical sources.

Naturalistic inquiry encompasses a wide array of both

primary and secondary research modes, which differ in

their depth of focus and degree of interpretation. Primary

modes have greater depth and interpretative level and are

represented most commonly by ethnography, grounded

theory, and phenomenology, but also include ethology,

ethnomethodology, hermeneutics, oral/life histories, dis-

course analysis, and critical and historical approaches to

inquiry. Each primary tradition has a distinct set of foun-

dational philosophical and theoretical orientations, strate-

gies for data collection and analysis, and forms of research

products. Secondary modes of naturalistic inquiry gener-

ally elicit more superficial-level data for categoric (descrip-

tive rather than interpretive) analysis; common types in-

clude focus groups, critical incident technique, case study

methodology, ethnoscience, and open, free-text responses.

The selection of a particular naturalistic approach de-

pends on the purpose of the research. For example, phe-

nomenology is the method of choice when the purpose is to

understand the meaning of the lived experience of a given

phenomenon for informants; grounded theory is selected

to uncover/understand basic social processes; and ethnog-

raphy is selected to understand patterns and/or processes

grounded in culture.

In most forms of naturalistic inquiry, investigators typ-

ically use one or a combination of strategies including

participant observation, informant interviews, and docu-

ment analysis. However, the extent to which the inves-

tigator relies on any one strategy will vary; for example,

phenomenology relies primarily on informant interviews,

ethnography has a more even balance between participant

observationand interviewing, and ethology relies primarily

on observations (Tripp-Reimer & Kelley 1998).

In summary, naturalistic inquiry most commonly occurs

in field settings with investigators collecting data through

participant observation and unstructured interviews, and

analyzing data through thematic content analysis.

USES OF QUALITATIVE APPROACHES

IN HEALTH RESEARCH

Qualitative approaches may be employed for a wide va-

riety of purposes related to health services and transla-

tional research. Five specific topics are addressed below

ranging fromvariable identificationto instrumentation, de-

scription/understanding of lay and provider behaviors, the-

ory construction/refinement, and synthesis for developing

practice guidelines.

Variable Identication

At the most foundational level, qualitative approaches are

often used to clarify concepts and constructs, and to or-

der them vertically and horizontally in the form of tax-

onomies. These standardized languages and classification

systems commonly form the basis for effective research us-

ing large datasets. Two nursing standardized languages, the

Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC; Dochterman &

Bulechek 2004) and the Nursing Outcomes Classification

(NOC; Moorhead, Johnson & Maas 2004) were developed

at the University of Iowa using the ethnoscience approach.

Further, Kuzel et al. (2003) demonstrated the utility of this

approach for constructing typologies of errors experienced

by patients and contrasting them with that of physicians;

they found that most technical definitions fail to capture

many types of errors of greatest concern to patients.

Instrumentation

Qualitative approaches are often used to develop or refine

data collection instruments. Prior to instrument construc-

tion, interviews (either individual or group) are commonly

used to establish content domains and generate specific

items. After instrument construction, these same methods,

as well as formal cognitive interviews, may be used to as-

sess the adequacy of the instruments or to understand re-

sponse difficulties and variations. For example, while qual-

itative approaches were used in the initial development of

the Picker (adapted from the Picker-Commonwealth Sur-

vey of Patient-Centered Care) and Consumer Assessment

of Health Plans Survey (Adult) (CAHPS 2.0) instruments,

they were also employed in later evaluations of their suit-

ability for different populations. Ngo-Metzger et al. (2003)

identified important aspects of the quality of care for Chi-

nese and Vietnamese immigrants not included in these in-

struments. Important missing domains in the Picker and

CAHPS instruments included (a) provider respect for tradi-

tional healthbeliefs andpractices, (b) access toprofessional

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

r

Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004 S67

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational Research

interpreters (and quality of interpreters), and (c) assistance

in obtaining social services.

Description/Understanding Phenomena

Perhaps the most frequent use of qualitative approaches is

for understanding the phenomena that are context depen-

dent. Broad domains include understanding patient and

provider perceptions and behaviors, as well as the process

of individual and organizational change.

Patient Experiences and Behaviors

Hundreds of qualitative studies have been conducted to

describe and understand patient experiences, preferences,

needs, and satisfaction. Projects have described what it is

like to live with a specific illness such as headache (Peters,

Abu-Saad, Vydelingum & Murphy 2002) or cystic fibro-

sis (Gjengedal, Rustoen, Wahl & Hanestad 2003); how the

context of care affects experiences such as dying (Mur-

ray, Grant, Grant & Kendall 2003) or self-reliance with

sickle cell disease (Maxwell, Streetly & Bevan 1999); how

perceived needs (Detaille, Haafkens & van Dijk 2003) or

quality-of-care domains (Curtis et al. 2002) differ across

different groups of chronically ill patients. Evans (2002,

p. 290) points out how these studies provide a strategy to

give consumers a voice in clinical decision making through

documenting their experiences, preferences, and priorities.

Studies of patient behaviors have provided important

insights regarding the basis for specific patient behaviors

including patterns of service utilization (Kelly & Groff

2000), the logic of noncompliance (Trostle 1997), and vari-

ation in triggers and barriers to change for various health-

related behaviors (Currie, Amos & Hung 1991). Power

(2002) points out howqualitative approaches have demon-

strated utility in areas where the social phenomena may be

highly personal, sensitive, and sometimes illicit, as with

much of HIV/AIDS research where these methods have

greatly increased our understanding of cultural influences

on lifestyles, risk negotiation around sex and drug inject-

ing, and health or identity disclosures.

Provider Perspectives and Behaviors

While provider behaviors have been a relatively recent fo-

cus oninquiry, this is a rapidly developing area andincludes

domains related to interaction/communication, provider

behavior, and the process of clinical decision making. Stud-

ies of interaction/communication have contributed to our

understanding of the ways providers strategically estab-

lish and maintain unequal power relations (Rapp 1988)

and how the different realities of providers and patients re-

sult inmiscommunicationandmisunderstandings (Cohen,

Tripp-Reimer, Smith, Sorofman & Lively 1994; Green &

Britten 1998; Gjengedal et al. 2003).

Several descriptive studies have investigated provider-

prescribing behavior related to pain management (Rogers

2002) or antibiotic use (Walker, McGeer, Simor,

Armstrong-Evans & Loeb 2000; Radyowijati & Haak

2003). These have clear implications for planning interven-

tions to alter provider behavior in translational research.

Changing Provider Behavior and Health Systems

A number of studies have investigated the phenomena of

practice change, particularly noting barriers to change.

Many barriers are based on providers perceptions of pa-

tient views, preferences, or characteristics. Patients views

of their own illness may affect their compliance (Green &

Britten 1998) or their preferences for treatment. For ex-

ample, an investigation of unnecessary antibiotic prescrib-

ing indicated that providers actions relied more heavily

on their views of patient preferences for antibiotics than

on their own knowledge of scientific recommendations

(Butler, Rollnick, Pill, Maggs-Rapport & Stott 1998); they

suggested that greater practice change would result from

interventions targeting clinical interactions rather than

education. Patient characteristics also may influence ap-

plication of practice guidelines. An investigation of low

adherence to hypertension practice protocols for geri-

atric patients found that providers viewed their patients

other problems as more significant and were also con-

cerned about the greater likelihood of adverse effects of

medications in elders (Cranney, Warren, Barton, Gardner

& Walley 2001).

Other studies have targeted the ways in which organiza-

tional context and professional environment affect use of

practice protocols. For example, available time and level

of expertise affected how residents obtained evidence for

clinical decision making (Montori, Tabini &Ebbert 2002).

Similarly, local provider culture was shown to create a local

consensus of practice knowledge that strongly influenced

the interpretation and weighting of newscientific evidence

(Fairhurst & Huby 1998).

A few studies have specifically focused on strategies

for guideline implementation, such as use of ward rounds

(Deshpande, Publicover, Gee & Khan 2003). Other ap-

proaches have examined how different groups of stake-

holders vary in their uptake of practice guidelines. Allery,

Owen, and Robling (1997) used critical incident technique

to explore how general practitioners and specialists dif-

fer in triggers and sources of evidence underlying prac-

tice changes. Using Giorgis phenomenological method,

Andersen (2002) examined important differences in bar-

riers to implementing a medication tracking system as ex-

perienced by nurse managers and physicians.

In perhaps the most comprehensive study of barriers

and facilitators to guideline implementation, Doebbeling et

al. (2002)conducted 50 focus groups with three categories

of stakeholders (administrators, primary care providers,

and clinicians) at 20 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers in

S68 Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004

r

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational Research

the United States. Annually, the Veterans Health Adminis-

tration rolls out different clinical practice guidelines and

monitors compliance with them, making this an excellent

environment for translational science. Perceived major fa-

cilitators to guideline implementation included admin-

istrative commitment, electronic patient records, work

reorganization, and audit with feedback. Major barriers

included time and workload issues, lack of technologi-

cal support, and lack of guideline credibility. Providers

(primarily physicians) and clinicians (primarily nurses)

emphasized barriers and problems with clinical prac-

tice guidelines, while administrators emphasized guideline

benefits andfacilitators to implementation. The groups also

differed in the major concerns expressed: Administrators

emphasized guideline compliance; providers emphasized

continuity of care; and clinicians emphasized benefits for

patients (Doebbeling et al. 2002; Sorofman et al. 2002;

Vaughn et al. 2002; Lyons et al. 2003). Taken as a whole,

these studies illustrate that implementing effective organi-

zational change requires attention to the issues of each key

stakeholder group.

Theory Construction/Renement

Qualitative approaches are not only useful for generat-

ing hypotheses, but also for theory development and re-

finement. An illustration of this point was made by the

Doebbeling et al. (2002) team investigating barriers and

facilitators to clinical practice guideline implementation

in the VHA. After completing the qualitative data analysis

from the 50 focus groups, they mapped the codes to the

framework developed by Kitson, Harvey, and McCormack

(1998) to depict implementation of clinical practice

guidelines. The model by Kitson et al. contains three

major domains: evidence (research, clinical experience,

and patient preferences), context (culture, leadership,

and measurement), and facilitation (characteristics, role,

and style). Recommendations for refinement of the Kit-

son model included adding guideline characteristics to

the evidence domain, deleting measurement from and

adding organizational characteristics to the context do-

main, and adding implementation strategies/processes

to the facilitation domain (Tripp-Reimer & Doebbeling

2003).

In summary, the naturalistic and qualitative approaches

are escalating in use and importance in all health research

and are increasingly important in translational

INTEGRATING QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

INTO SYNTHESIZED EVIDENCE REPORTS

In translational research, there have been several re-

cent, but highly significant, events and activities pro-

moting and facilitating the incorporation of the results

of naturalistic studies into synthesized evidence reports

(e.g., clinical practice guidelines). In Britain, the Na-

tional Health Service Center for Reviews and Dissem-

ination called for the inclusion of qualitative data in

its syntheses, and the Cochrane Qualitative Group has

been responsive to this mandate. The University of Es-

sex established a qualitative dataset of patient responses

that is now a part of the Economic and Social Data

Services (ESDS) Qualidata that is in the public domain

(http://www.esds.ac.uk/qualidata/online); a second estab-

lished resource, DIPEx, contains a large set of interviews

describing patient experiences that may be used by clini-

cians, instructors, or investigators (http://www.dipex.org).

The utility of qualitative data in systematic reviews can

be demonstrated through a delineation of the several roles

it can play including (a) clarifying the focus of the review;

(b) identifying the relevant types of participants, interven-

tions, and outcomes; (c) providing data for a qualitative

synthesis; (d) explaining unexpected findings of quantita-

tive studies; (e) interpreting the significance and applica-

bility of the review; and (f) suggesting bothclinical and pol-

icy recommendations for implementation (Dixon-Woods,

Fitzpatrick & Roberts 2001).

Four major approaches have been proposed for the

systematic synthesis of qualitative data. The first two

approachesthe Case Survey Method (Yin & Heald 1975)

and the Qualitative Comparative Method (Ragin 1987)

translate the qualitative data into numerical data, and then

analyze those data using statistics. The two newer ap-

proaches retain the qualitative character of the data and are

termed meta-ethnography (Noblit & Hare 1988) and meta-

synthesis (Sandelowski, Docherty & Emden 1997; Thorne

et al. 2002; Finfgeld 2003; Sandelowski & Barroso 2003)

and were developed by anthropologists and nurse scien-

tists, respectively.

Despite the recognized utility of qualitative data for syn-

thesis in practice guidelines, there are several problems

with the operationalization of this plan. Not the least of

the concerns involves difficulties in conducting literature

searches for the qualitative studies, including the frequent

use of witty or obscure titles, lack of standardized terms

inabstracts, andvariationinindexing across the wide range

of journals (Cesario, Morin & Santa-Donato 2002; Evans

2002; Hawker, Payne, Kerr, Hardey & Powell 2002; Bar-

roso et al. 2003). Furthermore, there is variation in eval-

uating both the quality (rigor) and the level of evidence

of the results, although several recent strategies have been

put forth (Popay, Rogers & Williams 1998; Giacomini &

Cook 2000a, 2000b; Cesario, Morin &Santa-Donato 2002;

Fossey, Harvey, McDermott & Davidson 2002; Hawker,

Payne, Kerr, Hardey & Powell 2002). While there is yet

no consensus regarding the best approach for qualitative

data synthesis, the Cochrane Qualitative Group is making

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

r

Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004 S69

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational Research

excellent progress in formulating such recommendations,

as are individual scientists such as Greenhalgh (2002).

SUMMARY

The unprecedented proliferation of qualitative research in

health sciences can be attributed to an increased empha-

sis on the components of quality of care and a mandate

to ensure that health care decisions are made on the best

available evidence. In the context of health research in

general, and translational research in particular, qualita-

tive approaches are making distinct and important contri-

butions through the illuminating and explanatory power

of these forms of evidence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Insti-

tutes of Health grant P30 NR03979 awarded to Dr. Tripp-

Reimer and by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans

Health Administration, Health Services Research and De-

velopment Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initia-

tive (QUERI), Investigator Initiated Research Grants CPI

99-126 and CPI 01-141, awarded to Dr. Doebbeling.

References

Adams K. & Corrigan J.M. (Eds.). (2003). Priority

areas for national action: Transforming health care

quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies

Press.

Allery L.A., Owen P.A. & Robling M.R. (1997). Why gen-

eral practitioners and consultants change their clinical

practice: A critical incident study. British Medical Jour-

nal, 314(7084), 870874.

Andersen S.E. (2002). Implementing a new drug record

system: A qualitative study of difficulties perceived by

physicians and nurses. Quality and Safety in Health Care,

11(1), 1924.

Barroso J., Gollop C.J., Sandelowski M., Meynell J., Pearce

P.F. & Collins L.J. (2003). The challenges of searching

for and retrieving qualitative studies. Western Journal of

Nursing Research, 25(2), 153178.

Becker H.S., Geer B., Hughes E.C. & Strauss A. (1961).

Boys in white. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Butler C., Rollnick S., Pill R., Maggs-Rapport F. & Stott N.

(1998). Understanding the culture of prescribing: Qual-

itative study of general practitioners and patients per-

ceptions of antibiotics for sore throats. British Medical

Journal, 317(7159), 637642.

Cesario S., Morin K. & Santa-Donato A. (2002). Evaluat-

ing the level of evidence of qualitative research. Journal

of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 31(6),

708714.

Cohen M.Z., Tripp-Reimer T., Smith C., Sorofman B. &

Lively S. (1994). Explanatory models of diabetes: Patient

practitioner variation. Social Science and Medicine, 38(1),

5966.

Corrigan J.M., Eden J. &Smith B.M. (Eds.). (2002). Lead-

ership by example: Coordinating government roles in im-

proving health care quality. Washington, DC: The Na-

tional Academies Press.

Cranney M., Warren E., Barton S., Gardner K. & Walley

T. (2001). Why do GPs not implement evidence-based

guidelines? A descriptive study. Family Practice, 18(4),

359363.

Currie C.E., Amos A. & Hung S.J. (1991). The dynam-

ics and processes of behavioral change in five classes of

health-related behaviorFindings from qualitative re-

search. Health Education Research, 6(4), 443453.

Curtis J.R., Wenrich M.D., Carline J.D., Shannon S.E.,

Ambrozy D.M. &Ramsey P.G. (2002). Patients perspec-

tives on physician skill in end-of-life care: Differences

between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest,

122(1), 356362.

Deshpande N., Publicover M., Gee H. &Khan K.S. (2003).

Incorporating the views of obstetric clinicians in imple-

menting evidence-supported labour and delivery suite

ward rounds: A case study. Health Information and Li-

braries Journal, 20(2), 8694.

Detaille S.I., Haafkens J.A. & van Dijk F.J. (2003). What

employees with rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus

and hearing loss need to cope at work. Scandinavian

Journal for Work Environment Health, 29(2), 134142.

Devers K.J., Sofaer S. &Rundall T.G. (Eds.). (1999). Quali-

tative methods in health services research, a special sup-

plement to HSR. Health Services Research, 34(5 Pt 2),

10831163.

Dixon-Woods M., Fitzpatrick R. & Roberts K. (2001). In-

cluding qualitative research in systematic reviews: Op-

portunities and problems. Journal of Evaluation in Clini-

cal Practice, 7(2), 125133.

Dochterman J. & Bulechek G. (Eds.). (2004). Nursing in-

terventions classication (NIC) (4th ed.). St. Louis, MO:

Mosby.

Doebbeling B.N., Vaughn T.E., Woolson R.F., Peloso P.,

Ward M.M., Letuchy E., BootsMiller B.J., Tripp-Reimer

T. & Branch L.G. (2002). Benchmarking Veterans Af-

fairs Medical Centers in the delivery of preventive health

services: Comparison of methods. Medical Care, 40(6),

540554.

Evans D. (2002). Database searches for qualitative research.

Journal of the Medical Library Association, 90(3), 290

293.

Evans-Pritchard E.E. (1937). Witchcraft, oracles, and magic

among the Azande. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Fairhurst K. &Huby G. (1998). Fromtrial data to practical

S70 Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004

r

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational Research

knowledge: Qualitative study of how general practition-

ers have accessed and used evidence about statin drugs

in their management of hypercholesterolaemia. British

Medical Journal, 317(7166), 11301134.

Finfgeld D.L. (2003). Metasynthesis: The state of the artso

far. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 893904.

Fossey E., Harvey C., McDermott F. &Davidson L. (2002).

Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aus-

tralian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6),

717732.

Gebbie K., Rosenstock L. & Hernandez L.M. (Eds.).

(2003). Who will keep the public healthy? Educating pub-

lic health professionals for the 21st century. Washington,

DC: The National Academies Press.

Giacomini M.K. & Cook D.J. (2000a). Users guides to the

medical literature XXIII. Qualitative research in health

care A. Are the results of the study valid? Journal of the

American Medical Association, 284(3), 357362.

Giacomini M.K. & Cook D.J. (2000b). Users guides to the

medical literature XXIII. Qualitative research in health

care B. What are the results and how do they help me

care for my patients? Journal of the American Medical

Association, 284(4), 478482.

Gjengedal E., Rustoen T., Wahl A.K. & Hanestad B.R.

(2003). Growing up and living with cystic fibrosis: Ev-

eryday life and encounters with the health care and so-

cial servicesa qualitative study. Advances in Nursing

Science, 26(2), 149159.

Goffman E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation

of mental patients and other inmates. Garden City, NY:

Doubleday Anchor Books.

Goffman E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of

spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Green J. & Britten N. (1998). Qualitative research

and evidence based medicine. British Medical Journal,

316(7139), 12301232.

Greenhalgh T. (2002). Integrating qualitative research into

evidence based practice. Endocrinology and Metabolism

Clinics of North America, 31(3), 583601.

Hawker S., Payne S., Kerr C., Hardey M. &Powell J. (2002).

Appraising the evidence: Reviewing disparate data sys-

tematically. Qualitative Health Research, 12(9), 1284

1299.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A

new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC:

The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2002). Speaking of health: Assessing

health communication strategies for diverse populations.

Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jones R. (1995). Why do qualitative research? British Med-

ical Journal, 311(6996), 2.

Kelly N.R. & Groff J.Y. (2000). Exploring barriers to uti-

lization of poison centers: Aqualitative study of mothers

attending an urban women, infants, and children (WIC)

clinic. Pediatrics, 106(1 Pt 2), 199204.

Kitson A., Harvey G. & McCormack B. (1998). Enabling

the implementation of evidence based practice: A con-

ceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7(3), 149

158.

Kuzel A.J., Woolf S.H., Engel J.D., Gilchrist V.J., Frankel

R.M., La Veist T.A. & Vincent C. (2003). Making the

case for a qualitative study of medical errors in pri-

mary care. Qualitative Health Research, 13(6), 743

780.

Lyons S.S., Tripp-Reimer T., Sorofman B., DeWitt J.,

BootsMiller B. & Doebbeling B.N. (2003). Clinical prac-

tice guidelines and computers: Variation in stakeholder is-

sues. 27th Annual Midwest Nursing Research Society

Conference, Grand Rapids, MI, April 47, 2003.

Maxwell K., Streetly A. & Bevan D. (1999). Experiences

of hospital care and treatment-seeking behavior for pain

fromsickle cell disease. Western Journal of Medicine, 171,

306313.

Montori V.M., Tabini C.C. &Ebbert J.O. (2002). A qualita-

tive assessment of 1st-year internal medicine residents

perceptions of evidence-based clinical decision making.

Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 14(2), 114118.

Moorhead S., Johnson M. & Maas M. (Eds.). (2004). Nurs-

ing outcomes classication (NOC) (3rd ed.). St. Louis,

MO: Mosby.

Murray S.A., Grant E., Grant A. & Kendall M. (2003).

Dying from cancer in developed and developing coun-

tries: Lessons from two qualitative interview studies

of patients and their carers. British Medical Journal,

326(7385), 368371.

Ngo-Metzger Q., Massagli M.P., Clarridge B.R., Manocchia

M., Davis R.B., Iezzoni L.I. & Phillips R.S. (2003). Lin-

guistic and cultural barriers to care: Perspectives of Chi-

nese and Vietnamese immigrants. Journal of General In-

ternal Medicine, 18(1), 4452.

Noblit G.W. & Hare R.D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Syn-

thesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Publications.

Peters M., Abu-Saad H.H., Vydelingum V. & Murphy M.

(2002). Research into headaches: The contribution of

qualitative methods. Headache, 42(10), 10511059.

Popay J., Rogers A. & Williams G. (1998). Rationale and

standards for the systematic review of qualitative liter-

ature in health services research. Qualitative Health Re-

search, 8(3), 341351.

Pope C., van Royen P. &Baker R. (2002). Qualitative meth-

ods in research on healthcare quality. Quality and Safety

in Health Care, 11(2), 148152.

Power R. (2002). The application of qualitative research

methods to the study of sexually transmitted infections.

Sexually Transmitted Infection, 78(2), 8789.

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

r

Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004 S71

Qualitative Perspectives in Translational Research

Radyowijati A. &Haak H. (2003). Improving antibiotic use

in low-income countries: An overview of evidence on

determinants. Social Science and Medicine, 57(4), 733

744.

Ragin C.C. (1987). The comparative method: Moving beyond

qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkeley, CA: Uni-

versity of California Press.

Rapp R. (1988). Chromosomes and communication: The

discourse of genetic counseling. Medical Anthropology

Quarterly, 2(2), 143157.

Rivers W.H.R. (1924). Medicine, magic, and religion. New

York: Harcourt Brace.

Rogers W.A. (2002). Whose autonomy? Which choice? A

study of GPs attitudes towards patient autonomy in the

management of low back pain. Family Practice, 19(2),

140145.

Sandelowski M. &Barroso J. (2003). Toward a metasynthe-

sis of qualitative findings onmotherhoodinHIV-positive

women. Research in Nursing & Health, 26(2), 153

170.

Sandelowski M., Docherty S. &EmdenC. (1997). Focus on

qualitative methods. Qualitative metasynthesis: Issues

and techniques. Research in Nursing & Health, 20(4),

365371.

Shortell S. (1999). The emergence of qualitative methods in

health services research. Health Services Research, 34(5

Pt 2), 10831090.

Smedley B.D. & Syme S.L. (Eds.). (2000). Promoting

health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral

research. Washington, DC: The National Academies

Press.

Smedley B.D., Stith A.Y. &Nelson A.R. (Eds.). (2003). Un-

equal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities

in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies

Press.

SorofmanB.N., Tripp-Reimer T., DeWitt J., BootsMiller B.J.,

VaughnT.E., Ward M.M. &Doebbeling B.N. (2002). Dif-

fering views of clinical practice guidelines: Variation by role

responsibility. Poster at the VA Health Services Research

and Development 20th Annual Meeting, Washington,

DC, February 1315, 2002.

Thorne S., Paterson B., Acorn S., Canam C., Joachim G. &

Jillings C. (2002). Chronic illness experience: Insights

from a metastudy. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4),

437452.

Tripp-Reimer T. & Doebbeling B.N. (2003). Qualitative ap-

proaches in translational research. Paper at the Advanc-

ing Quality Care Through Translational Research, U.S.

Invitational Conference, Iowa City, IA, October 1314,

2003.

Tripp-Reimer T. & Kelley L. (1998). Qualitative research.

In J. Fitzpatrick (Ed.), Encyclopedia of nursing research.

New York: Springer Publishing.

Trostle J.A. (1997). The history and meaning of patient

compliance as an ideology. In D.S. Gochman (Ed.),

Handbook of health behavior research II: Provider deter-

minants. New York: Plenum Press.

Vaughn T.E., McCoy K., BootsMiller B.J., Woolson R.F.,

Sorofman B., Tripp-Reimer T., Perlin J. & Doebbel-

ing B.N. (2002). Organizational predictors of adherence

to ambulatory care screening guidelines. Medical Care,

40(12), 11721185.

Walker S., McGeer A., Simor A.E., Armstrong-Evans M.

& Loeb M. (2000). Why are antibiotics prescribed for

asymptomatic bacteriuria in institutionalized elderly

people? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 163(3),

273277.

Yin R.K. & Heald K.A. (1975). Using the case survey

method to analyze policy studies. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 20, 371381.

S72 Third Quarter (Suppl.) 2004

r

Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing

You might also like

- Public Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandPublic Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Evidence Based Practive 2006Document15 pagesEvidence Based Practive 2006Bolo GanNo ratings yet

- Best Practices For Mixed Methods ResearchDocument39 pagesBest Practices For Mixed Methods Researchscribd104444No ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Nursing Practice For Health Promotion in Adults With Hypertension: A Literature ReviewDocument19 pagesEvidence-Based Nursing Practice For Health Promotion in Adults With Hypertension: A Literature ReviewYusvita WaliaNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Nursing Practice For Health Promotion in Adults With Hypertension: A Literature ReviewDocument38 pagesEvidence-Based Nursing Practice For Health Promotion in Adults With Hypertension: A Literature Reviewmarisa isahNo ratings yet

- Conjoint in HEALTH ResearchDocument17 pagesConjoint in HEALTH ResearchDiana Tan May KimNo ratings yet

- 8-2 Health Services Research Translating Research Into PolicyDocument39 pages8-2 Health Services Research Translating Research Into PolicyFady Jehad ZabenNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesPrimary Health Care Literature Reviewafdtbluwq100% (1)

- Session 7Document76 pagesSession 7priyanshiraichada15No ratings yet

- America's Healthcare Transformation: Strategies and InnovationsFrom EverandAmerica's Healthcare Transformation: Strategies and InnovationsNo ratings yet

- Peer-Reviewed Example PaperDocument4 pagesPeer-Reviewed Example PaperEunique NoelNo ratings yet

- Ramseier Et Al-2015-Journal of Clinical Periodontology PDFDocument12 pagesRamseier Et Al-2015-Journal of Clinical Periodontology PDFChristine HacheNo ratings yet

- Health Service Research An Evolving Definition of The FieldDocument3 pagesHealth Service Research An Evolving Definition of The FieldSamNo ratings yet

- A Framework To Measure The Impact of Investments in Health ResearchDocument16 pagesA Framework To Measure The Impact of Investments in Health ResearchGesler Pilvan SainNo ratings yet

- What Is Health Services ResearchDocument5 pagesWhat Is Health Services ResearchClara Bermúdez TamayoNo ratings yet

- Quality Improvement ModelsDocument64 pagesQuality Improvement ModelsShahin Patowary100% (2)

- The Integration of Primary Health Care Services A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesThe Integration of Primary Health Care Services A Systematic Literature ReviewrdssibwgfNo ratings yet

- Sdi 5294 KumarDocument20 pagesSdi 5294 KumarBharatKumarMaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Patient CenteredDocument12 pagesPatient CenteredNina NaguyevskayaNo ratings yet

- 2012 Bigbee Models PHNDocument11 pages2012 Bigbee Models PHNJulia Dewi Eka GunawatiNo ratings yet

- Public Health Dissertation TitlesDocument7 pagesPublic Health Dissertation TitlesWriteMyPaperPleaseSingapore100% (1)

- Closing The Quality Gap-A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement StrategiesDocument206 pagesClosing The Quality Gap-A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategiesturbina155No ratings yet

- Faber - Public Reporting in Health CareDocument8 pagesFaber - Public Reporting in Health CareDaniel Rico FuentesNo ratings yet

- HLRP 0220 CudjoeDocument24 pagesHLRP 0220 CudjoeaaanzaniiNo ratings yet

- Quality Indicators For Primary Health Care A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesQuality Indicators For Primary Health Care A Systematic Literature ReviewafdtygyhkNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading MavDocument2 pagesJournal Reading MavCuttie Anne GalangNo ratings yet

- Mr. Hariom Rajput Mr. Ramsingh Ji Gmail-ID International Association of Oncology (IAO) Government of IndiaDocument6 pagesMr. Hariom Rajput Mr. Ramsingh Ji Gmail-ID International Association of Oncology (IAO) Government of IndiaHariom RajputNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of The Professional Pharmacy Services in A Major Canadian Hospital: A Comparison of Stakeholder GroupsDocument12 pagesPerceptions of The Professional Pharmacy Services in A Major Canadian Hospital: A Comparison of Stakeholder GroupsGracia GiasiNo ratings yet

- Intergrative Review Final DraftDocument22 pagesIntergrative Review Final Draftapi-432119884No ratings yet

- Guide To Patient and Family Engagement: Environmental Scan ReportDocument100 pagesGuide To Patient and Family Engagement: Environmental Scan ReportjustdoyourNo ratings yet

- 0rder 343 NRS-493-ASSIGNMENT 3 Literature ReviewDocument6 pages0rder 343 NRS-493-ASSIGNMENT 3 Literature Reviewjoshua chegeNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Health Policy: A Preliminary Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesEvidence-Based Health Policy: A Preliminary Systematic ReviewAndre LanzerNo ratings yet

- Quality of Healthcare Services Rural IndiaDocument10 pagesQuality of Healthcare Services Rural IndiaPradeep BishtNo ratings yet

- Health Care Quality Assessment: Michael A. Counte, PH.DDocument30 pagesHealth Care Quality Assessment: Michael A. Counte, PH.DAnonymous TO9fMjNo ratings yet

- Measuring Oral Health and Quality of LifeDocument172 pagesMeasuring Oral Health and Quality of LifeCalin Dragoman100% (1)

- Models For Individual Oral Health Promotion and Their Effectiveness: A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesModels For Individual Oral Health Promotion and Their Effectiveness: A Systematic ReviewMonica Agustine HartonoNo ratings yet

- C Truong, M., Paradies, Y. & Priest, N. (2014Document17 pagesC Truong, M., Paradies, Y. & Priest, N. (2014Ign EcheverríaNo ratings yet

- Sabitha PROJECT SYNOPSISDocument4 pagesSabitha PROJECT SYNOPSISJohn MohanNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading ReportDocument2 pagesJournal Reading ReportCuttie Anne GalangNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal For Public Health: A New ChecklistDocument7 pagesCritical Appraisal For Public Health: A New Checklistkristina dewiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Developing Competencies For Health Promotion Deliverable 3bDocument10 pagesLiterature Review Developing Competencies For Health Promotion Deliverable 3bxfeivdsifNo ratings yet

- Systematic Literature Review of Oral HygieneDocument52 pagesSystematic Literature Review of Oral HygieneAnkit Kothiyal0% (1)

- Evidence Based Practice in Nursing BinuDocument51 pagesEvidence Based Practice in Nursing BinuBinu Joshva100% (3)

- 1 - 4 Quality of CareDocument10 pages1 - 4 Quality of CareRaul Gascueña100% (1)

- How Can Clinical Epidemiology Better Support Evidence-Based Guidelines and Policies in Low-Income CountriesDocument3 pagesHow Can Clinical Epidemiology Better Support Evidence-Based Guidelines and Policies in Low-Income CountriesEko Wahyu AgustinNo ratings yet

- SAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inDocument21 pagesSAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inascarolineeNo ratings yet

- Patient Engagement in Research: A Systematic Review: Researcharticle Open AccessDocument9 pagesPatient Engagement in Research: A Systematic Review: Researcharticle Open Accessv_ratNo ratings yet

- Effects of Worksite Health Promotion Interventions On Employee Diets: A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesEffects of Worksite Health Promotion Interventions On Employee Diets: A Systematic ReviewUtami LukitaNo ratings yet

- Integrative Health Care Shift Benefits and Challenges Among Health Care ProfessionalsDocument4 pagesIntegrative Health Care Shift Benefits and Challenges Among Health Care ProfessionalsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Health Seeking BehaviourDocument27 pagesHealth Seeking BehaviourRommel IrabagonNo ratings yet

- Taxonomia BCWDocument216 pagesTaxonomia BCWMae SilvaNo ratings yet

- Nursing ResearchDocument15 pagesNursing Researchsubhashreepal13No ratings yet

- HLTH 520 Reseach Appraisal - ResearchDocument16 pagesHLTH 520 Reseach Appraisal - Researchapi-479186899No ratings yet

- Summary ResearchDocument6 pagesSummary ResearchLance SilvaNo ratings yet

- Ahrq DissertationDocument4 pagesAhrq Dissertationsupnilante1980100% (1)

- Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology ProjectDocument41 pagesWriting The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Projectrcaba100% (1)

- Psychiatry Research: Alison B. Hamilton, Erin P. Finley TDocument8 pagesPsychiatry Research: Alison B. Hamilton, Erin P. Finley TEloisa Garcia AñinoNo ratings yet

- Plos Medicine /Article/Crossref/I /Article/Tw Itter/Info /Article/Metrics/Inf Info:Doi/10.1371/J Patient Adher 1185260400000Document25 pagesPlos Medicine /Article/Crossref/I /Article/Tw Itter/Info /Article/Metrics/Inf Info:Doi/10.1371/J Patient Adher 1185260400000khattak_i89No ratings yet

- Accelerating Medical Evidence Generation and Use: Summary of a Meeting SeriesFrom EverandAccelerating Medical Evidence Generation and Use: Summary of a Meeting SeriesNo ratings yet

- Cahn&Polich - 06 Meditation States and Traits ReviewDocument33 pagesCahn&Polich - 06 Meditation States and Traits ReviewfiseradaNo ratings yet

- Membertou Family Homes Law Fact SheetDocument2 pagesMembertou Family Homes Law Fact SheetfiseradaNo ratings yet

- Cultural Sensitivity and Adaptation in Family Based Prevention InterventionsDocument6 pagesCultural Sensitivity and Adaptation in Family Based Prevention Interventionsfiserada100% (1)

- Shojin Ryori Culinary Fundamentals in Zen PDFDocument1 pageShojin Ryori Culinary Fundamentals in Zen PDFfiseradaNo ratings yet

- Tsung-Mi and The Single Word "Awareness" (Chih) by Peter GregoryDocument20 pagesTsung-Mi and The Single Word "Awareness" (Chih) by Peter GregoryfiseradaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Systematic Reviews Road Map V3Document2 pagesDiagnostic Systematic Reviews Road Map V3fiseradaNo ratings yet

- Large SystemsDocument220 pagesLarge SystemsfiseradaNo ratings yet

- Making Outcome Mapping WorkDocument79 pagesMaking Outcome Mapping WorkfiseradaNo ratings yet

- How Far Can Q-Analysis Go Into Social Systems Understanding ?Document10 pagesHow Far Can Q-Analysis Go Into Social Systems Understanding ?fiseradaNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Instrument DesignDocument28 pagesInnovation in Instrument DesignfiseradaNo ratings yet

- Diavik Fact BookDocument20 pagesDiavik Fact BookfiseradaNo ratings yet

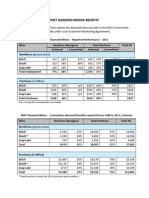

- NWT Diamond Mining Benefits: N/a - No Specific Commitments Were MadeDocument2 pagesNWT Diamond Mining Benefits: N/a - No Specific Commitments Were MadefiseradaNo ratings yet

- Economic Resilience To DisastersDocument59 pagesEconomic Resilience To DisastersfiseradaNo ratings yet

- Biblical Hebrew A Text and WorkbookDocument451 pagesBiblical Hebrew A Text and Workbookannegh100% (4)