Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Final Paper

Final Paper

Uploaded by

api-249528937Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 17 The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children's Executive FunctionDocument8 pages17 The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children's Executive FunctionClaudia Ulloa MoralesNo ratings yet

- Running Head: RESEARCH PROPOSAL 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: RESEARCH PROPOSAL 1hjogoss0% (1)

- Executive Function The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children'sDocument8 pagesExecutive Function The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children'sNoel NecroNo ratings yet

- Does Viewing Television Affect The Academic Performance of ChildrenDocument5 pagesDoes Viewing Television Affect The Academic Performance of ChildrenCastolo Bayucot JvjcNo ratings yet

- Proposal RM Watching TelevisionDocument10 pagesProposal RM Watching TelevisionAlawiah IsmailNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 0193397380900611 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 0193397380900611 MainIrada AliyevaNo ratings yet

- KaufmanDocument5 pagesKaufmanGabriella HarasztiNo ratings yet

- Troles BA PsychologyDocument43 pagesTroles BA Psychologymko.iwoNo ratings yet

- Reel TimeDocument26 pagesReel TimeAmen MartzNo ratings yet

- Comparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaresDocument6 pagesComparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaressdanobeitiaNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Effects of TV Viewing On The Adjustment of Adolescents in Relation To Their Academic PerformanceDocument14 pagesCumulative Effects of TV Viewing On The Adjustment of Adolescents in Relation To Their Academic PerformancePuspita Eka Kurnia SariNo ratings yet

- Two-Year Findings From A National Effectiveness Trial - Effectiveness of Behavioral and Non-Behavioral Parenting ProgramsDocument16 pagesTwo-Year Findings From A National Effectiveness Trial - Effectiveness of Behavioral and Non-Behavioral Parenting ProgramsJuliana ZardiniNo ratings yet

- Measuring Attention in Very Old Adults Using The Test of Everyday AttentionDocument5 pagesMeasuring Attention in Very Old Adults Using The Test of Everyday AttentionpoohyeeNo ratings yet

- Television EffectsDocument8 pagesTelevision EffectsAnca RoxanaNo ratings yet

- BMC Public HealthDocument15 pagesBMC Public HealthLateecka R KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Peer Review Journal ArticleDocument7 pagesPeer Review Journal Articleapi-507432876No ratings yet

- Cadangan Kajian 2Document4 pagesCadangan Kajian 2Zakiah MdyusofNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Think-Aloud Questionnaires and IntDocument12 pagesA Comparison of Think-Aloud Questionnaires and IntnaafNo ratings yet

- Huber2018 PDFDocument14 pagesHuber2018 PDFFarin MauliaNo ratings yet

- Early Television Exposure and Subsequent Attentional Problems in ChildrenDocument6 pagesEarly Television Exposure and Subsequent Attentional Problems in Childrenxiejie22590No ratings yet

- Influence of Heavy and Low Television Watching On Study Habits of Secondary School StudentsDocument3 pagesInfluence of Heavy and Low Television Watching On Study Habits of Secondary School StudentsTimothy ArthurNo ratings yet

- DFE RR142a PDFDocument80 pagesDFE RR142a PDFAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Trajectories of Sustained Attention DevelopmentDocument14 pagesLongitudinal Trajectories of Sustained Attention DevelopmentedgarNo ratings yet

- Running Header: Educational Videos in The Classroom 1Document13 pagesRunning Header: Educational Videos in The Classroom 1api-239909726No ratings yet

- Bedtime Routines For Young ChildrenDocument6 pagesBedtime Routines For Young ChildrenmithaNo ratings yet

- 03 - Tomar JournalDocument9 pages03 - Tomar Journalvinoelnino10No ratings yet

- Suess2013 PDFDocument26 pagesSuess2013 PDFNBNo ratings yet

- Experimental ReportDocument3 pagesExperimental Reportesthermuthoni3001No ratings yet

- The Effect of Watching Television Programs With Strong Parental Guidance RatingDocument27 pagesThe Effect of Watching Television Programs With Strong Parental Guidance RatingJohn Andrei DepliyanNo ratings yet

- TV Mancare Cross CulturalDocument7 pagesTV Mancare Cross CulturalMihai RoxanaNo ratings yet

- Screen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep DurationDocument10 pagesScreen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep Durationdwi putri ratehNo ratings yet

- Interaction of Media, Sexual Activity & Academic Achievement in AdolescentsDocument6 pagesInteraction of Media, Sexual Activity & Academic Achievement in AdolescentsFlorina AndreiNo ratings yet

- Law and Human Behavior: Children's Performance On Ground Rules Questions: Implications For Forensic InterviewingDocument40 pagesLaw and Human Behavior: Children's Performance On Ground Rules Questions: Implications For Forensic Interviewingjr7101159No ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument9 pagesReview of Related Literature and StudiesMary John Bautista TolegaNo ratings yet

- Group 4 Lived Experiences On Parental Guiding Original.Document10 pagesGroup 4 Lived Experiences On Parental Guiding Original.Richmar Tabuelog CabañeroNo ratings yet

- Relations of Television Viewing and Reading: Findings From A 4-Year Longitudinal StudyDocument21 pagesRelations of Television Viewing and Reading: Findings From A 4-Year Longitudinal StudyJonathan García VilledaNo ratings yet

- Anderson2007 PecsDocument10 pagesAnderson2007 PecsLarisa NaeNo ratings yet

- Sleep and Study Time Final PaperDocument6 pagesSleep and Study Time Final Paperapi-251993533No ratings yet

- Myopic Shift and Outdoor Activity Among PrimaryDocument8 pagesMyopic Shift and Outdoor Activity Among PrimaryJkey HooNo ratings yet

- Title Proposal JustificationsDocument2 pagesTitle Proposal Justificationsaprilstamaria0427No ratings yet

- Demand Characteristics in UI ResearchDocument5 pagesDemand Characteristics in UI ResearchanuragsaksenacNo ratings yet

- Effects of Television Viewing On Adolescents of 17 To 19 YearsDocument5 pagesEffects of Television Viewing On Adolescents of 17 To 19 YearsJorge SotoNo ratings yet

- Final Research Paper 1Document5 pagesFinal Research Paper 1api-293221238No ratings yet

- Screen Time Differences Among Turkish University Students As An Indicator of Sedentary Lifestyle and InactivityDocument26 pagesScreen Time Differences Among Turkish University Students As An Indicator of Sedentary Lifestyle and Inactivityaimifarzana98No ratings yet

- DM Assignment 2b Article ReviewDocument3 pagesDM Assignment 2b Article ReviewDikesh MaharjanNo ratings yet

- The Correlation Between Watching English Movies Habit and The Listening Achievement of The Freshmen StudentDocument7 pagesThe Correlation Between Watching English Movies Habit and The Listening Achievement of The Freshmen StudentDestaRizkhyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document38 pagesChapter 1aprilstamaria0427No ratings yet

- Screen Time ChildDocument11 pagesScreen Time ChildTere NavaNo ratings yet

- The Associations Between Near Visual Activity and Incident Myopia in Children: A Nationwide 4-Year Follow-Up StudyDocument8 pagesThe Associations Between Near Visual Activity and Incident Myopia in Children: A Nationwide 4-Year Follow-Up StudyHeiddy Ch SumampouwNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Repetition On Imitation From Television During InfancyDocument12 pagesThe Effect of Repetition On Imitation From Television During Infancyalex_brito84No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Critical ReviewDocument7 pagesAssignment 1 Critical Reviewcjwilliams6No ratings yet

- 4 Bavelier 2010 Children Wired For Better or Worse PDFDocument10 pages4 Bavelier 2010 Children Wired For Better or Worse PDFMalou Mico CastilloNo ratings yet

- OSF FinalDocument38 pagesOSF Finalinas zahraNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Screen Time and Sleep Among Finnish Preschool ChildrenDocument28 pagesRelationship Between Screen Time and Sleep Among Finnish Preschool ChildrenJúlio EmanoelNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Assessment Labels On The Testing EffectDocument9 pagesThe Influence of Assessment Labels On The Testing EffectFrancesca BowserNo ratings yet

- Visual Search Task ReportDocument16 pagesVisual Search Task ReportUmmu MukhlisNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Training On A Young Child With Cortical Visual Impairment An Exploratory StudyDocument16 pagesThe Effects of Training On A Young Child With Cortical Visual Impairment An Exploratory StudyShobithaNo ratings yet

- El Tipo de Tiempo de Pantalla, Modera Los Efectos Sobre Los Resultados en 4013 Niños, Videncia Del Estudio Longitudinal de Niños AustralianosDocument10 pagesEl Tipo de Tiempo de Pantalla, Modera Los Efectos Sobre Los Resultados en 4013 Niños, Videncia Del Estudio Longitudinal de Niños AustralianosIVAN DARIO RODRIGUEZ SALAMANCANo ratings yet

- Fa Com BSTDocument18 pagesFa Com BSTana lara SantosNo ratings yet

- Quality Criteria in children TV: Narrative and Script Writing for Children’s TV 0-6From EverandQuality Criteria in children TV: Narrative and Script Writing for Children’s TV 0-6No ratings yet

- SS Disco Check Valve (Size 15-100)Document2 pagesSS Disco Check Valve (Size 15-100)rudirstNo ratings yet

- Ede Micro Project For Tyco StudentsDocument10 pagesEde Micro Project For Tyco StudentsAditya YadavNo ratings yet

- Diffraction GratingsDocument5 pagesDiffraction GratingsJohn JohnsonNo ratings yet

- CDAP006 Subfloor Protection PDFDocument2 pagesCDAP006 Subfloor Protection PDFGustavo Márquez TorresNo ratings yet

- En SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13Document1 pageEn SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13emadsafy20002239No ratings yet

- TM-Editor 25.04.2016 Seite 1 050-Meteorology - LTMDocument308 pagesTM-Editor 25.04.2016 Seite 1 050-Meteorology - LTMIbrahim Med100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0920586123000196 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0920586123000196 Mainsofch2011No ratings yet

- Types of Variables (In Statistical Studies) - Definitions and Easy ExamplesDocument9 pagesTypes of Variables (In Statistical Studies) - Definitions and Easy ExamplesAntonioNo ratings yet

- Dipesh Document INTERNSHIPDocument28 pagesDipesh Document INTERNSHIPthakurgokhul862No ratings yet

- Konstantinos Georgiadis, Th.D. Religion and Law Teacher/ Greek Secondary EducationDocument2 pagesKonstantinos Georgiadis, Th.D. Religion and Law Teacher/ Greek Secondary EducationPablo CanovasNo ratings yet

- Vietnam SPC - Vinyl Price ListDocument9 pagesVietnam SPC - Vinyl Price ListThe Cultural CommitteeNo ratings yet

- Nynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetDocument1 pageNynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetAnonymous S29FwnFNo ratings yet

- Carbon Dioxide CO2 SensorDocument4 pagesCarbon Dioxide CO2 SensorgouttNo ratings yet

- DLP in IctDocument3 pagesDLP in Ictreyna.sazon001No ratings yet

- 19Document227 pages19Miguel José DuarteNo ratings yet

- MC Practicals 2Document12 pagesMC Practicals 2Adi AdnanNo ratings yet

- How To Implement SAP NoteDocument13 pagesHow To Implement SAP NoteSurya NandaNo ratings yet

- Swati Bajaj ProjDocument88 pagesSwati Bajaj ProjSwati SoodNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Scientific Understanding of Behavior: Learning ObjectivesDocument13 pagesChapter 1: Scientific Understanding of Behavior: Learning Objectiveshallo BroNo ratings yet

- SYNTHESIS Filipino 1Document6 pagesSYNTHESIS Filipino 1DhanNo ratings yet

- Chavan Avinash-Resume 2Document1 pageChavan Avinash-Resume 2Adinath Baliram ShelkeNo ratings yet

- SEFI General Discussion35Document4 pagesSEFI General Discussion35blisscutest beagleNo ratings yet

- Revision On Unit 1,2 First Secondry (Hello)Document11 pagesRevision On Unit 1,2 First Secondry (Hello)Vivian GendyNo ratings yet

- Questão 20: Língua Inglesa 11 A 20Document3 pagesQuestão 20: Língua Inglesa 11 A 20Gabriel TeodoroNo ratings yet

- The Ethnography of Communication: Mădălina MATEIDocument8 pagesThe Ethnography of Communication: Mădălina MATEIamir_marzbanNo ratings yet

- Development of Automated Aerial Pesticide SprayerDocument6 pagesDevelopment of Automated Aerial Pesticide SprayeresatjournalsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document24 pagesChapter 6گل میوہNo ratings yet

- Business ResearchsampleDocument38 pagesBusiness Researchsamplebasma ezzatNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT 1 FinalsDocument2 pagesASSIGNMENT 1 FinalsAnne Dela CruzNo ratings yet

Final Paper

Final Paper

Uploaded by

api-249528937Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Final Paper

Final Paper

Uploaded by

api-249528937Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

Effects of Two Television Shows on Children and Adolescents Reading Performance Aliza Markert B00580441 Dalhousie University PSYO 3091 February 29th, 2012

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Abstract

The goal of the present study was to examine whether the rate of scene changes in a television show immediately influenced reading performance. Little research has been done on the immediate effects of television, and studies that have been done have had mixed results. A total of 37 individuals, aged four to 22 years, participated in the study. Each participant completed a speeded reading task, watched a 10 minute video clip of either a fast-paced or slow-paced television show, and then completed another, qualitatively equivalent, speeded reading task. It was hypothesized that participants in the fast-paced group would perform worse on the posttest than individuals in the slow-paced group, but no significant differences in scores based on video condition were found. The researchers conclude that the effect of the pace of scene changes on attention is still unclear, and that more research is required to expand our understanding of the topic. Keywords: Reading performance, television, rate of scene change, speeded reading task

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

Effects of Two Television Shows on Children and Adolescents Reading Performance Most children in todays society watch a great deal of television, and many of the shows are fast-paced cartoons with rapid flashing of movement. Do these fast-paced cartoons have a negative effect on childrens functioning? Lillard and Peterson (2011) conducted an experiment in an attempt to answer this question by examining if children who watch a fast-paced television show perform worse on tasks testing executive function immediately after watching the show than children who were drawing or watching an educational show. The present study used a modified version of the Lillard and Peterson study to further explore this question. A great deal of research has been conducted to address the various long-term effects television may have on children. Koolstra and van der Voort (2006) conducted a three-year longitudinal study examining the effects of television viewing on frequency of reading and found that television was associated with a decline in book reading. The data also suggested that a causal mechanism that can explain the reduced level of reading is that television may induce deterioration in childrens ability to concentrate on reading. This is important because it suggests that television watching has a negative effect on concentration and attention. Interestingly, these results are inconsistent with an earlier study, which found that television watching was not consistently related to amount of time spent reading or reading skill (Ritchie, Price, & Roberts, 1987). Ennemoser and Schneider (2007) conducted a four-year longitudinal study to examine the effects of television viewing on childrens reading competency. After recording televisionwatching habits and conducting annual reading tests, it was found that there is an interaction between television and reading competency, but it depends on the type of television being

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

watched. Educational television programs were associated with high reading competency, while entertainment programs were associated with lower reading competency. Okuma and Tanimura (2009) looked at the specific characteristics of television shows, and found that high amounts of movement and transformation are associated with language delays in young children. Determining that the type and characteristics of the television being watched influences the effects on reading and literacy was an important discovery, and went one step beyond the Ritchie et al. (1987) and Koolstra and van der Voort (2006) studies. Despite an abundance of studies focused on the long-term effects of television, there is little research on the immediate effects of television viewing. In a recent meta-analysis on the impact of television viewing on literacy development, for example, the pacing of television shows was not addressed, nor was the immediate effect of watching television (Moses, 2008). One of the few experiments focused on the immediate effects of television was a study examining the effects of highly arousing and fast-paced television on processing and encoding of the content (Lang, Bolls, Potter, & Kawahara, 1999). It was found that fast-paced television overloaded the processing system, leading to less recognition and cued recall. This provides evidence that fast-paced television had negative effects. Cooper, Uller, Pettifer, and Stolc (2009) also examined the immediate effects of television, focusing on whether the speed of editing of a program affects attention. Speed of editing is the rate of fast edits and scene changes. In this between-subjects manipulation, children aged 4-7 watched either a fast-edited show or a slow-edited show. Immediately after finishing the video, children completed a task testing three components of attention. One of the components assessed was orienting, which was defined as the process of choosing a specific stimulus from a number of options. Overall reaction times and error rates were also measured.

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

It was found that orienting scores were better for four year old children in the slow-edited group than the fast edited group, but that children over the age of six had better orienting scores in the fast-edited group than in the slow-edited group. Furthermore, the children in the fast-edited video group made fewer errors on the attention task than the children in the slow-edited group. Lillard and Peterson (2011) conducted a study testing whether fast-paced television shows impair the executive functioning of four-year-old children. The pace of the television shows was measured by the frequency of complete scene changes. This method did not measure switches in camera shots and angles, but measured the lengths of full scenes in the television show. Executive functioning involves skills associated with the prefrontal cortex. These skills underlie goal-directed behaviour, and include things such as attention, self-regulation, problem solving, delayed gratification, inhibitory control, and working memory. A between subjects design with three conditions was used to test the effects of different activities on executive functioning (Lillard & Peterson, 2011). In the first condition, children watched a nine minute clip of the fast-paced television show SpongeBob SquarePants. In the second condition children watched an educational television show for nine minutes, and in the third condition children were asked to draw for nine minutes. After watching television or drawing, all participants completed four tasks to test their executive functioning. One of the tasks was a delayed gratification test where children were told they would get a little bit of a certain snack if they chose to eat it when they wanted to and that they would get a larger amount of the snack if they were able to wait for a signal from the experimenter. Another of the tasks was a backward digit span, where a set of digits was read out loud, and the child had to repeat them to the researcher in the reverse order of which they were presented. While the children

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE were completing these tasks, their parents filled out questionnaires about their patterns of attention and the amount of time they spend watching television each week. The self-report questionnaires filled out by parents indicated that there were no

significant differences in the average amount of television watched per week or in the general patterns of attention in the children (Lillard & Peterson, 2011). Even though there were no previous differences in attention or television-watching patterns, the children who watched the fast-paced television show did significantly worse on the executive functioning tasks than the children in the other conditions. Specifically, the children in the fast-paced group performed significantly worse than both the educational program group and the drawing group on the delayed gratification task, while on the other three tasks they performed significantly worse than the drawing group, and the differences from the educational group approached significance. Results indicated that the drawing condition and the educational program condition did not differ from one another on their performance on the tests of executive functioning. Because the body of research on immediate effects of television on children is limited and has demonstrated inconsistent results, more studies are needed to discover more about this concept. There are a number of variables of interest in the present experiment. For the purposes of this study, reading performance can be defined as the speed and accuracy at which participants are able to read a group of words. The rate of scene change is also important. A scene change can be defined as each time the set, or scenery changes. This may be a change in camera angle from displaying one character or object to another character or object, a change from a close-up shot to a wide-angle shot, or a full change in the surrounding scenery, such as a change from being in a restaurant to being in a car. A continuous perspective change (such as zooming in or out, or a pan shot) does not count as a scene change. For example, if the camera is focused on a

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

certain character and then physically moves, while still filming, to view another character, it does not count as a scene change. If the camera switches from one character to another using different camera shots, it does count as a scene change. There are a number of grey areas in distinguishing what counts as a scene change. When switching from one scenario to another, there may be some sort of transition picture that crosses the screen. In SpongeBob SquarePants, for example, bubbles are often used to fill the screen when changing to a new segment of the show. The transition picture in itself does not count as a scene. In other words, if the video was showing characters in a restaurant, bubbles crossed the screen, and then they were shown in a car, it would count as only one scene change. A fast-paced television show can be defined as an animated television show aimed at youth that has frequent scene changes. Conversely, a slowpaced television show can be defined as an animated television show aimed at youth that has a slower rate of scene changes. The present study, a modified version of the Lillard and Peterson (2011) experiment, used a between-subjects manipulation in which participants viewed one of two video clips, a fast-paced television show or a slow-paced show. All participants completed speeded reading tests prior to and following watching the clip. The use of a pre-test and post-test design instead of the self-report measures used by Lillard and Peterson allows the researchers to address changes in performance without relying on parental self-report information. It was predicted that participants watching the fast-paced television show would perform worse on the reading posttest than the pretest and that participants watching the slow-paced television show would not show these differences, and would have similar scores on both tests. In other words, it was expected that the posttest scores of the children watching the fast-paced show would be lower than the scores of the children watching the slow-paced show.

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Method Participants

A total of 37 individuals (Mage = 12.49 years, age range: four-22 years) participated in the present study. Three participants were between the ages of four and five, seven were between the ages of six and eight, six were between the ages of nine and 11, seven were between the ages of 12 and 14, 12 were between the ages of 15 and 17, and three were between the ages of 18 and 22. A convenience sample was used, where participants were chosen based on social connections of the experimenters. Though the youngest participant was four years old, the minimum acceptable age of participants was three years and this limitation was chosen based on the difficulty level of the reading task that all were required to complete as a part of the study. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision. This criteria increased internal validity by ensuring that all children participating in the study were able to see the video clip and read the letters and words in the reading task the same way that the other children would. Additionally, all participants were required to have English as a first language and be enrolled in English school. Individuals with English as a second language, simultaneous bilingual children, and those who first learned to read in a language other than English may have an underlying difference in their interpretation and understanding of the English language. Because this difference has the potential to skew the results of the study, only children who had English as a first language (for both reading and writing) were able to participate. Children with seizure disorders or learning disabilities were not able to participate in the study because of the task requirements of the experiment.

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Materials

Video clips. Each participant viewed one of two 10 minute video clips on a 13 inch laptop computer. One of the video clips features the fast-paced television show SpongeBob SquarePants, commonly referred to as just SpongeBob, which is broadcasted on YTV. A wide range of children, from preschoolers to adolescents, watch this television show. The series centers on the adventures of the title character, SpongeBob SquarePants, and his friends, who live in the ocean in the underwater city of Bikini Bottom. During the episode featured in the video clip, entitled Welcome to the Chum Bucket, SpongeBob is forced to leave the restaurant he works at in order to work for another restaurant, whose owner wants to know the secret recipes from SpongeBobs regular restaurant. The other video clip features the animated slowpaced educational television show Sid the Science Kid, which is aired on PBS. This television show primarily targets young children. The series provides information about basic scientific principles and how things work through the use of Sid, the inquisitive main character. During the episode featured in the video clip, entitled I want to be a Scientist, Sid and his classmates go to the local science center and learn about various careers involving science. In each video clip, the first 10 minutes of the episode after the main title were shown to participants. Both episodes are commercial-free. SpongeBob is a fast-paced television show, with each scene shot lasting an average of 3.5 seconds, which results in about 17 scene changes per minute. In contrast, Sid the Science Kid has somewhat longer scenes, lasting an average of 4.5 seconds. In this television show, there are about 13 scene changes per minute. These numbers were calculated by measuring the time intervals between scene changes while watching the video and averaging the numbers. A scene change was defined as each time the set, or scenery changes. This may be a change in camera angle from displaying one character or object to another

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

10

character or object, a change from a close-up shot to a wide-angle shot, or a full change in the surrounding scenery. A continuous perspective change (such as zooming in or out, or a pan shot) does not count as a scene change. When switching from one scenario to another, there may be some sort of transition picture that crosses the screen. In SpongeBob SquarePants, for example, bubbles are often used to fill the screen when changing to a new segment of the show. The transition picture in itself does not count as a scene. Speeded reading task. Two versions of a speeded reading test were created by modifying the TOWRE, a standardized reading assessment (Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte 1999). The TOWRE consists of lists of increasingly difficult words, beginning with single syllable words and ending with complex multisyllabic words. The present study accommodated pre-school aged children by adding an initial section with individual letters. To modify the task, all experimenters split into small groups and re-wrote one of two TOWRE word lists, adding individual letters at the beginning of the list. To re-write the lists, each word on the TOWRE was examined, and an equivalent word was generated based on the print frequency of the word, the syllable length and complexity, and the number of syllables. For example, the word no would be a good replacement for so, but the word then would not be a good replacement for so. Once all the researchers had created modified word lists, they were put together and compacted into two 110 item lists. List one features items such as C, What, and Restitution (see Appendix A), while list two features items such as S, Learn, and Transient (see Appendix B). The lists are assumed to be qualitatively equal. An 11 item practice list was also developed for participants (see Appendix C). Experimenter sheets were developed for word list one (see Appendix D) and word list two (see Appendix E) to enable the researcher to follow along and follow the progress of the participant using a pencil and paper

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

11

recording method. A cell phone timer was used as a stopwatch to record times for the speeded reading tasks. Each participant completed both versions of the task, but the order in which they were completed depended on the result of a counterbalancing procedure. Procedure Multiple experimenters were involved in the data collection process, with each individual testing one child. Each experimenter met with the child and a legal guardian on a local university campus or in their home to carry out the experiment. Data was collected over a three week period. Prior to beginning the procedure, consent of the parent or guardian and assent of the child were given. During the procedure, each child completed one of the word lists for the speeded reading task, then watched one of the 10-minute video clips, and finished by completing the other word list for the speeded reading task. In total, the procedure took a maximum of 30 minutes. Counterbalancing was used to determine which video each child would watch and the order in which they took the speeded reading tests. Children who watched the SpongeBob video were group A, and those who watched Sid the Science Kid were group B. The order in which the child completed the speeded reading tests was determined by the experimenters last name, divided so that half of the participants would have list one as the pretest and half would have list two as the pretest. Following the initial greetings and consent procedure, the experimenter and the participant found a comfortable, quiet space with few distractions. Once the child was settled, the experimenter gave verbal instructions for the speeded reading test. The child was instructed to read each word as quickly and accurately as possible, reading the words in order down the vertical columns. They were also asked to follow along with their finger to indicate which word

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

12

they were reading at the time. Additionally, they were instructed to sound out any words that they did not know. Once it was confirmed that the child understood the instructions, the practice sheet was given to the child and they were asked to go through the words as directed in the instructions. During the practice session, the experimenter answered any questions the child had and corrected any mistakes they may have made. Once they had completed the practice, the practice sheet was returned to the researcher. The child was told that the next list of words would be longer and that they should read the words consecutively in the same way as in the practice until they were told to stop. The child was then given either word list one or word list two, depending on their placement from the counterbalancing procedure. If the child appeared confused in any way, they were asked simple questions to test their understanding of the task. Once the experimenter was confident that the child was ready to complete the pretest, they handed the child the word list. Meanwhile, the researcher had the experimenter sheet for the corresponding word list in front of them. The experimenter told the participant to begin as they started a 45 second timer. As the child went through the words, the experimenter followed along on their sheet to ensure the words were read correctly and in order. Any incorrect or skipped responses were marked with a slash on the experimenter sheet. If the child began with an incorrect response but corrected themselves, the word still counted as a part of their score but the correction was noted on the experimenter sheet. Conversely, if they start by pronouncing it correctly but repeat it incorrectly, it was counted as being incorrect. Once the 45 second timer went off, the child was asked to stop and return the word list. The word number on the experiment sheet was recorded. A total score was calculated by subtracting the number of skipped or incorrect responses from the word number of the last word read. The total time taken

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

13

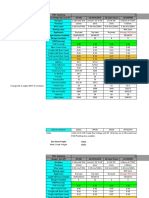

to read all words was recorded for any individuals who completed the entire word list within the 45-second time limit. Immediately after completing the speeded reading task, the child was shown one of the 10-minute video clips, depending on whether they were in group A or B. The videos were already set to begin after the opening titles and were stopped promptly after 10 minutes. The child was not permitted to continue watching the remainder of the episode before completing the posttest. Once the child had finished the video, they were reminded what they would need to do in the reading task. The posttest was executed the same way as the pretest, but used the word list that was not used in the pretest. Results The data were analyzed using a mixed ANOVA comparing the pretest and posttest scores as a function of three between-subjects variables. The first variable was age, which was split into young (age range: 4-14) and old (age range: 15-22). The second variable was condition, which represented whether the child watched the Spongebob video or the Sid the Science Kid video. Finally, the third variable was list order, which was whether the participant did list one first and list two second or if they did list two first and list one second. The results of the analysis revealed a number of non-significant effects, including the Pretest-Posttest X Age, PretestPosttest X Condition, Pretest-Posttest X List Order, Pretest-Posttest X Age X Condition, PretestPosttest X Condition X List Order, and Pretest-Posttest X Age X Condition X List Order interactions (ps > .05). The analysis also indicated a significant three-way way Pretest-Posttest X Age X List Order interaction, F(1, 29) = 4.20, p = .05. A list order effect can be seen in the old age group, where in the 1-2 list order the score decreases on the posttest (Mpretest = 96.4, Mposttest = 92.8), but in the 2-1 list order the score increases on the posttest (Mpretest = 95.1, Mposttest

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

14

= 98.1; see Figure 1). A main effect of age was also found, where the older group (M = 95.6 (SE = 6.31)) scored higher than the younger group (M = 52.60 (SE = 5.69)), F(1, 29) = 25.64, p < .001.

List Order 1-2

110 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 Pretest Posttest Old Young

List Order 2-1

110 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 Pretest Posttest Old Young

Figure 1. Change in test score from pretest to posttest in the young and old age groups for each list order.

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Discussion

15

Results indicate that the hypothesis was not supported because participants who watched the fast-paced television show did not perform significantly worse on the reading posttest than the participants who watched the slow-paced television show. In fact, neither video had any effect on list reading performance. Though the initial hypothesis was not supported, two significant results did emerge. One of these results was a main effect of age. The older age group performed significantly better on the reading tests than the younger group. This result is expected because older individuals would be expected to have more advanced reading skills than the younger group. The other significant result was a three-way interaction between age, list order, and pretest-posttest scores. The older group of individuals improved their performance on the posttest when they did list two first, but their performance decreased when they did list one first. This may indicate that there is a qualitative difference in the longer words on the list, those that the younger children did not reach, that made list two more difficult than list one. The finding that participants did not differ significantly on the posttest depending on video condition is inconsistent with the findings of Lillard and Peterson (2011), who found that children watching a fast-paced television show performed significantly worse on executive functioning than children watching an educational show or drawing. It is possible that these differences emerged because the type of tasks testing attention differed between the two experiments. Though Lillard and Peterson used a variety of tasks to test executive functioning, none of them involved reading performance. The different tasks may be testing different aspects of attention, which may be responsible for the difference in the results. The differing methodology in measuring scene changes may also account for these differences. The results of the present study do not match up with those of Lang et al. (1999) either, who found that fast-

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

16

paced television overloaded the processing system, leading to less recognition and cued recall. F Cooper et al. (2009), in contrast, found that participants watching fast-edited television actually made fewer errors on subsequent attention tasks than those in other conditions. Since the present study did not find any significant results in this area, it is inconsistent with all other studies to date that have examined the immediate effects of fast-paced television on attention. Regardless of the reasoning for the differences in results, it is clear that more research needs to be done to gain a better understanding of this issue. There are a number of limitations in the present study. One limiting factor was that a different researcher tested each participant. Though there was a general script to follow, small individual differences between researchers may have influenced results. For example, some researchers may have used a count-down timer with an alarm at the end while others may have used a count-up timer where they had to continually watch the clock whilst recording the childs performance on the word list. Those who used the count-up timer would likely have had a slight delay between seeing the time reach 45 seconds, registering it, and telling the child to stop reading. Because they were multitasking, also evaluating the childs performance, this may be delayed even more. In contrast, the alarm on the count-down timer would notify the child and researcher immediately when to stop. This small difference could change the results because the children subjected to the count-up timer may have had enough extra time to read more words than they would have with a count-down timer. Researchers using the count-up timer would also more easily lose track of the time, and there may even have been differences in the time allowed between the pretest and the posttest. This would be even more problematic because it would specifically affect the results indicating whether the participant did better or worse on the posttest.

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

17

Another limiting factor is that the present study cannot answer any questions about the influence of gender. During the study procedure, the gender of participants was not recorded. Because of this, the researchers cannot look at how males and females may differ in their reaction to fast-paced television. The gender of participants should have been recorded so that it could be added as a variable in the analyses. There are also limiting factors relating to the content of the video clips themselves. The video clips were both cut off in the middle of the television episode. If the participant was interested in the show, they may wonder what was going to happen next and be more distracted on the reading test than they would have been otherwise. Ideally, the video clips would be full episodes. If a regular 30 minute episode was longer than desired, a custom made video or different television show with shorter episodes could be used. Another potential issue with the video clips is that if the show was aimed towards a much younger age group than the individual watching, the participant may have become bored. This may have affected their attention and reading performance after the video clip. The television shows used were aimed at children and young adolescents, but 15 of the 37 participants were aged 15 or older. This indicates that a large group of the participants were in all likelihood not very interested in the video clip they were watching. Overall, the results of the present study indicate that neither fast-paced nor slow-paced television, when watched in short intervals, have an immediate effect on reading performance. This implies that parents do not need to be concerned if children are watching television for a short time before school or another activity requiring reading. They would also not need to be concerned with the speed of scene changes in the show. This conclusion, however, needs to be taken with caution due to the great deal of inconsistency in the results of similar studies (Cooper

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

18

et al., 2009; Lang et al., 1999; Lillard & Peterson, 2011). Though the present study has these implications, taken as a whole the literature in this area implies that the only conclusion that can be made is that more research and information is required before making any generalizations about the immediate affects of television on attention. Further research in this area should begin with more studies on short-term effects of fastpaced television on attention. In these studies the limitations of the present study should be met. Additionally, more unified definitions need to be used so that the study results can be effectively compared to one another. A unified definition of attention is required to ensure that the tasks testing attention are actually measuring the same processes. Additionally, a more specific definition of fast-paced television needs to be established. It must clearly outline what counts as a scene and give guidelines on how fast scene changes must be to qualify the television show as fast-paced. This is imperative because the present study could not be effectively compared to the Lillard and Peterson (2011) study it was based off of due to a major difference in method of measuring scene changes. Subsequent studies should examine the immediate effects of attention across multiple trials with each child. A greater variety of television shows should also be used in each new study, as this may reveal another factor other than the pace of scene change that affects attention. If, after getting more consistent results from studies on the short-term effects of fast-paced television on attention, it appears that this does have a negative effect, studies looking at long-term effects should also be done. Longitudinal studies would be useful to see if there is a dosage effect over time. If further research does indicate a significant negative effect of fast-paced television on attention, the general public would need to be aware of this. Parents should be informed to help them tailor what types of television their children are allowed to watch. If only immediate

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

19

effects on attention are found, this tailoring would only be necessary immediately before school or other activities requiring reading and attention. It should be noted, however, that it is ideal to always be fully attentive, so perhaps the fast-paced shows should be revised. If further research also indicates long-term negative effects of fast-paced television, these shows should definitely be eliminated. If that doesnt happen, parents must be aware of this so that they can consistently tailor the type of television being watched by their children rather than only before tasks requiring attentiveness.

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE References

20

Cooper, N. R., Uller, C. C., Pettifer, J. J., & Stolc, F. C. (2009). Conditioning attentional skills: Examining the effects of the pace of television editing on childrens attention. Acta Paediatrica, 98, 1651-1655. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01377.x Ennemoser, M., & Schneider, W. (2007). Relations of television viewing and reading: Findings from a 4-year longitudinal study. Journal Of Educational Psychology, 99, 349-368. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.349 Koolstra, C. M., & van der Voort, T. A. (1996). Longitudinal effects of television on children's leisure-time reading: A test of three explanatory models. Human Communication Research, 23, 4-35. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1996.tb00385.x Lang, A., Bolls, P., Potter, R. F., & Kawahara, K. (1999). The effects of production pacing and arousing content on the information processing of television messages. Journal Of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 43, 451-475. Lillard, A. S., & Peterson, J. (2011). The immediate impact of different types of television on young children's executive function. Pediatrics, 128, 644-649. doi: 10.1542/peds.20101919 Moses, A. M. (2008). Impacts of television viewing on young children's literacy development in the USA: A review of the literature. Journal Of Early Childhood Literacy, 8, 67-102. doi:10.1177/1468798407087162 Okuma, K., & Tanimura, M. (2009). A preliminary study on the relationship between characteristics of TV content and delayed speech development in young children. Infant Behavior & Development, 32, 312-321. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.04.002

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE

21

Ritchie, D., Price, V., & Roberts, D. F. (1987). Television, reading, and reading achievement: A reappraisal. Communication Research, 14, 292-315. doi:10.1177/009365087014003002 Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (1999). Comprehensive test of phonological processing. San Antonio, TX: Pearson.

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Appendix A

22

List 1 C P A U L F He Bag It Day As So Be Me Up Can Dig Get Box Big Note Bow Far Cook What Help Won Rug Work Able This Fort Shop Bead Pump Open Deal Lid Earth Some Five Apple Cake Train Both Have Good Spell Time Came Fact Rival Fairy Grape Trust Money Farmer Crowd Famous Black Party Stars Almost Child Visit Cover Music Human Great Something Contain History Justice Right Business Present Inquire Major Purchase Exercise Fireplace Animal Assume Mousse Believe Morning Finally Gasoline Question Balance Daughter Vacancy Elements Pioneer Excellent Gradually Indicate Boisterous Departure Salvation Acceptable Spurious Baroque Limousine Blacksmith Ornament Catalyst Grandiose Amateur Restitution

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Appendix B

23

List 2 S T N K M B Go Fit In Red Am To At We On Fox Car Yes Rat Boy Blue Look Him The Not Book How Door Fair Gone Now Let Next Baby Save Stop Jump Best Fast Oven Milk Did Start Lost Want Paper Even Learn Shoe Luck Wrong Other Care Heavy Short Truck People Winter Waves Forest Strong Thing Office Cross Better Never Given Vacant Huge Without Contact Abusive Invent Fruit Complete Resolve Instead River Garment Qualify Everyone Together Strange Horizon Dangerous Mountain Absentee Clarify Pleasant Mediate Distress Modulate Recession Emphasize Desperate Intuition Wonderful Plausible Courageous Necessary Factories Particular Extinguish Selection Verbatim Awkward Detective Dossier Instruction Transient

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Appendix C Practice List E X R On My Be Old Warm Bone Most Spell

24

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Appendix D

25

TELEVISION AND READING PERFORMANCE Appendix E

26

You might also like

- 17 The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children's Executive FunctionDocument8 pages17 The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children's Executive FunctionClaudia Ulloa MoralesNo ratings yet

- Running Head: RESEARCH PROPOSAL 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: RESEARCH PROPOSAL 1hjogoss0% (1)

- Executive Function The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children'sDocument8 pagesExecutive Function The Immediate Impact of Different Types of Television On Young Children'sNoel NecroNo ratings yet

- Does Viewing Television Affect The Academic Performance of ChildrenDocument5 pagesDoes Viewing Television Affect The Academic Performance of ChildrenCastolo Bayucot JvjcNo ratings yet

- Proposal RM Watching TelevisionDocument10 pagesProposal RM Watching TelevisionAlawiah IsmailNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 0193397380900611 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 0193397380900611 MainIrada AliyevaNo ratings yet

- KaufmanDocument5 pagesKaufmanGabriella HarasztiNo ratings yet

- Troles BA PsychologyDocument43 pagesTroles BA Psychologymko.iwoNo ratings yet

- Reel TimeDocument26 pagesReel TimeAmen MartzNo ratings yet

- Comparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaresDocument6 pagesComparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaressdanobeitiaNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Effects of TV Viewing On The Adjustment of Adolescents in Relation To Their Academic PerformanceDocument14 pagesCumulative Effects of TV Viewing On The Adjustment of Adolescents in Relation To Their Academic PerformancePuspita Eka Kurnia SariNo ratings yet

- Two-Year Findings From A National Effectiveness Trial - Effectiveness of Behavioral and Non-Behavioral Parenting ProgramsDocument16 pagesTwo-Year Findings From A National Effectiveness Trial - Effectiveness of Behavioral and Non-Behavioral Parenting ProgramsJuliana ZardiniNo ratings yet

- Measuring Attention in Very Old Adults Using The Test of Everyday AttentionDocument5 pagesMeasuring Attention in Very Old Adults Using The Test of Everyday AttentionpoohyeeNo ratings yet

- Television EffectsDocument8 pagesTelevision EffectsAnca RoxanaNo ratings yet

- BMC Public HealthDocument15 pagesBMC Public HealthLateecka R KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Peer Review Journal ArticleDocument7 pagesPeer Review Journal Articleapi-507432876No ratings yet

- Cadangan Kajian 2Document4 pagesCadangan Kajian 2Zakiah MdyusofNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Think-Aloud Questionnaires and IntDocument12 pagesA Comparison of Think-Aloud Questionnaires and IntnaafNo ratings yet

- Huber2018 PDFDocument14 pagesHuber2018 PDFFarin MauliaNo ratings yet

- Early Television Exposure and Subsequent Attentional Problems in ChildrenDocument6 pagesEarly Television Exposure and Subsequent Attentional Problems in Childrenxiejie22590No ratings yet

- Influence of Heavy and Low Television Watching On Study Habits of Secondary School StudentsDocument3 pagesInfluence of Heavy and Low Television Watching On Study Habits of Secondary School StudentsTimothy ArthurNo ratings yet

- DFE RR142a PDFDocument80 pagesDFE RR142a PDFAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Trajectories of Sustained Attention DevelopmentDocument14 pagesLongitudinal Trajectories of Sustained Attention DevelopmentedgarNo ratings yet

- Running Header: Educational Videos in The Classroom 1Document13 pagesRunning Header: Educational Videos in The Classroom 1api-239909726No ratings yet

- Bedtime Routines For Young ChildrenDocument6 pagesBedtime Routines For Young ChildrenmithaNo ratings yet

- 03 - Tomar JournalDocument9 pages03 - Tomar Journalvinoelnino10No ratings yet

- Suess2013 PDFDocument26 pagesSuess2013 PDFNBNo ratings yet

- Experimental ReportDocument3 pagesExperimental Reportesthermuthoni3001No ratings yet

- The Effect of Watching Television Programs With Strong Parental Guidance RatingDocument27 pagesThe Effect of Watching Television Programs With Strong Parental Guidance RatingJohn Andrei DepliyanNo ratings yet

- TV Mancare Cross CulturalDocument7 pagesTV Mancare Cross CulturalMihai RoxanaNo ratings yet

- Screen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep DurationDocument10 pagesScreen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep Durationdwi putri ratehNo ratings yet

- Interaction of Media, Sexual Activity & Academic Achievement in AdolescentsDocument6 pagesInteraction of Media, Sexual Activity & Academic Achievement in AdolescentsFlorina AndreiNo ratings yet

- Law and Human Behavior: Children's Performance On Ground Rules Questions: Implications For Forensic InterviewingDocument40 pagesLaw and Human Behavior: Children's Performance On Ground Rules Questions: Implications For Forensic Interviewingjr7101159No ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument9 pagesReview of Related Literature and StudiesMary John Bautista TolegaNo ratings yet

- Group 4 Lived Experiences On Parental Guiding Original.Document10 pagesGroup 4 Lived Experiences On Parental Guiding Original.Richmar Tabuelog CabañeroNo ratings yet

- Relations of Television Viewing and Reading: Findings From A 4-Year Longitudinal StudyDocument21 pagesRelations of Television Viewing and Reading: Findings From A 4-Year Longitudinal StudyJonathan García VilledaNo ratings yet

- Anderson2007 PecsDocument10 pagesAnderson2007 PecsLarisa NaeNo ratings yet

- Sleep and Study Time Final PaperDocument6 pagesSleep and Study Time Final Paperapi-251993533No ratings yet

- Myopic Shift and Outdoor Activity Among PrimaryDocument8 pagesMyopic Shift and Outdoor Activity Among PrimaryJkey HooNo ratings yet

- Title Proposal JustificationsDocument2 pagesTitle Proposal Justificationsaprilstamaria0427No ratings yet

- Demand Characteristics in UI ResearchDocument5 pagesDemand Characteristics in UI ResearchanuragsaksenacNo ratings yet

- Effects of Television Viewing On Adolescents of 17 To 19 YearsDocument5 pagesEffects of Television Viewing On Adolescents of 17 To 19 YearsJorge SotoNo ratings yet

- Final Research Paper 1Document5 pagesFinal Research Paper 1api-293221238No ratings yet

- Screen Time Differences Among Turkish University Students As An Indicator of Sedentary Lifestyle and InactivityDocument26 pagesScreen Time Differences Among Turkish University Students As An Indicator of Sedentary Lifestyle and Inactivityaimifarzana98No ratings yet

- DM Assignment 2b Article ReviewDocument3 pagesDM Assignment 2b Article ReviewDikesh MaharjanNo ratings yet

- The Correlation Between Watching English Movies Habit and The Listening Achievement of The Freshmen StudentDocument7 pagesThe Correlation Between Watching English Movies Habit and The Listening Achievement of The Freshmen StudentDestaRizkhyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document38 pagesChapter 1aprilstamaria0427No ratings yet

- Screen Time ChildDocument11 pagesScreen Time ChildTere NavaNo ratings yet

- The Associations Between Near Visual Activity and Incident Myopia in Children: A Nationwide 4-Year Follow-Up StudyDocument8 pagesThe Associations Between Near Visual Activity and Incident Myopia in Children: A Nationwide 4-Year Follow-Up StudyHeiddy Ch SumampouwNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Repetition On Imitation From Television During InfancyDocument12 pagesThe Effect of Repetition On Imitation From Television During Infancyalex_brito84No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Critical ReviewDocument7 pagesAssignment 1 Critical Reviewcjwilliams6No ratings yet

- 4 Bavelier 2010 Children Wired For Better or Worse PDFDocument10 pages4 Bavelier 2010 Children Wired For Better or Worse PDFMalou Mico CastilloNo ratings yet

- OSF FinalDocument38 pagesOSF Finalinas zahraNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Screen Time and Sleep Among Finnish Preschool ChildrenDocument28 pagesRelationship Between Screen Time and Sleep Among Finnish Preschool ChildrenJúlio EmanoelNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Assessment Labels On The Testing EffectDocument9 pagesThe Influence of Assessment Labels On The Testing EffectFrancesca BowserNo ratings yet

- Visual Search Task ReportDocument16 pagesVisual Search Task ReportUmmu MukhlisNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Training On A Young Child With Cortical Visual Impairment An Exploratory StudyDocument16 pagesThe Effects of Training On A Young Child With Cortical Visual Impairment An Exploratory StudyShobithaNo ratings yet

- El Tipo de Tiempo de Pantalla, Modera Los Efectos Sobre Los Resultados en 4013 Niños, Videncia Del Estudio Longitudinal de Niños AustralianosDocument10 pagesEl Tipo de Tiempo de Pantalla, Modera Los Efectos Sobre Los Resultados en 4013 Niños, Videncia Del Estudio Longitudinal de Niños AustralianosIVAN DARIO RODRIGUEZ SALAMANCANo ratings yet

- Fa Com BSTDocument18 pagesFa Com BSTana lara SantosNo ratings yet

- Quality Criteria in children TV: Narrative and Script Writing for Children’s TV 0-6From EverandQuality Criteria in children TV: Narrative and Script Writing for Children’s TV 0-6No ratings yet

- SS Disco Check Valve (Size 15-100)Document2 pagesSS Disco Check Valve (Size 15-100)rudirstNo ratings yet

- Ede Micro Project For Tyco StudentsDocument10 pagesEde Micro Project For Tyco StudentsAditya YadavNo ratings yet

- Diffraction GratingsDocument5 pagesDiffraction GratingsJohn JohnsonNo ratings yet

- CDAP006 Subfloor Protection PDFDocument2 pagesCDAP006 Subfloor Protection PDFGustavo Márquez TorresNo ratings yet

- En SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13Document1 pageEn SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13emadsafy20002239No ratings yet

- TM-Editor 25.04.2016 Seite 1 050-Meteorology - LTMDocument308 pagesTM-Editor 25.04.2016 Seite 1 050-Meteorology - LTMIbrahim Med100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0920586123000196 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0920586123000196 Mainsofch2011No ratings yet

- Types of Variables (In Statistical Studies) - Definitions and Easy ExamplesDocument9 pagesTypes of Variables (In Statistical Studies) - Definitions and Easy ExamplesAntonioNo ratings yet

- Dipesh Document INTERNSHIPDocument28 pagesDipesh Document INTERNSHIPthakurgokhul862No ratings yet

- Konstantinos Georgiadis, Th.D. Religion and Law Teacher/ Greek Secondary EducationDocument2 pagesKonstantinos Georgiadis, Th.D. Religion and Law Teacher/ Greek Secondary EducationPablo CanovasNo ratings yet

- Vietnam SPC - Vinyl Price ListDocument9 pagesVietnam SPC - Vinyl Price ListThe Cultural CommitteeNo ratings yet

- Nynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetDocument1 pageNynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetAnonymous S29FwnFNo ratings yet

- Carbon Dioxide CO2 SensorDocument4 pagesCarbon Dioxide CO2 SensorgouttNo ratings yet

- DLP in IctDocument3 pagesDLP in Ictreyna.sazon001No ratings yet

- 19Document227 pages19Miguel José DuarteNo ratings yet

- MC Practicals 2Document12 pagesMC Practicals 2Adi AdnanNo ratings yet

- How To Implement SAP NoteDocument13 pagesHow To Implement SAP NoteSurya NandaNo ratings yet

- Swati Bajaj ProjDocument88 pagesSwati Bajaj ProjSwati SoodNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Scientific Understanding of Behavior: Learning ObjectivesDocument13 pagesChapter 1: Scientific Understanding of Behavior: Learning Objectiveshallo BroNo ratings yet

- SYNTHESIS Filipino 1Document6 pagesSYNTHESIS Filipino 1DhanNo ratings yet

- Chavan Avinash-Resume 2Document1 pageChavan Avinash-Resume 2Adinath Baliram ShelkeNo ratings yet

- SEFI General Discussion35Document4 pagesSEFI General Discussion35blisscutest beagleNo ratings yet

- Revision On Unit 1,2 First Secondry (Hello)Document11 pagesRevision On Unit 1,2 First Secondry (Hello)Vivian GendyNo ratings yet

- Questão 20: Língua Inglesa 11 A 20Document3 pagesQuestão 20: Língua Inglesa 11 A 20Gabriel TeodoroNo ratings yet

- The Ethnography of Communication: Mădălina MATEIDocument8 pagesThe Ethnography of Communication: Mădălina MATEIamir_marzbanNo ratings yet

- Development of Automated Aerial Pesticide SprayerDocument6 pagesDevelopment of Automated Aerial Pesticide SprayeresatjournalsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document24 pagesChapter 6گل میوہNo ratings yet

- Business ResearchsampleDocument38 pagesBusiness Researchsamplebasma ezzatNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT 1 FinalsDocument2 pagesASSIGNMENT 1 FinalsAnne Dela CruzNo ratings yet