Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Success Formulas For Shopping Centres in Romania

Success Formulas For Shopping Centres in Romania

Uploaded by

Raul VasvariCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Linear ProgrammingDocument6 pagesLinear ProgrammingabeerNo ratings yet

- Armstrong's Handbook of Management and Leadership For HR - 4thDocument472 pagesArmstrong's Handbook of Management and Leadership For HR - 4thMichael Phan100% (2)

- Major Project ReportDocument48 pagesMajor Project Reportinderpreet kaurNo ratings yet

- Marketing 302 CocacolaDocument3 pagesMarketing 302 Cocacolamasfiq HossainNo ratings yet

- Mẫu kế hoạch truyền thôngDocument5 pagesMẫu kế hoạch truyền thôngHoanganh SetupNo ratings yet

- (68433)Document2 pages(68433)esseesse76No ratings yet

- Categorization of Evaluation Techniques-1Document16 pagesCategorization of Evaluation Techniques-1Krushna KhedkarNo ratings yet

- Credit Policy and Procedure ManualDocument4 pagesCredit Policy and Procedure ManualRafiq AhmedNo ratings yet

- Applying The Restatement Approach Under IAS 29 Financial Reporting in Hyperinflationary EconomiesDocument6 pagesApplying The Restatement Approach Under IAS 29 Financial Reporting in Hyperinflationary EconomiesJames BarzoNo ratings yet

- LG Mission, Vision & Values LG Mission StatementDocument9 pagesLG Mission, Vision & Values LG Mission StatementQasim MughalNo ratings yet

- Suppliers Assessment ChecklistDocument3 pagesSuppliers Assessment ChecklistRonnel LeanoNo ratings yet

- ISO 13485 2016 Documentation Manual Clause Wise RequirementsDocument15 pagesISO 13485 2016 Documentation Manual Clause Wise Requirementsqmicertification100% (1)

- Breadtalk CEO BT ArticleDocument4 pagesBreadtalk CEO BT ArticleScott LeeNo ratings yet

- Finone: Cost or Current Repurchase Price) Undiscounted Amount ofDocument7 pagesFinone: Cost or Current Repurchase Price) Undiscounted Amount ofStephanie Queen OcampoNo ratings yet

- Transcript of Interview With Walter Casey: Walter Casey, Binghampton Favorite Son, Is Celebrated For His WorkDocument6 pagesTranscript of Interview With Walter Casey: Walter Casey, Binghampton Favorite Son, Is Celebrated For His Workapi-339753830No ratings yet

- Gaap Graded2016Document385 pagesGaap Graded2016Venniah Musunda100% (1)

- Avoiding The Bertrand Trap II: CooperationDocument29 pagesAvoiding The Bertrand Trap II: CooperationPua Suan Jin RobinNo ratings yet

- Mission, Vision, Goal, and Objective PDFDocument68 pagesMission, Vision, Goal, and Objective PDFtjpkNo ratings yet

- KRA KPI Mohammed SalesDocument6 pagesKRA KPI Mohammed Salesdominic.penielNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Supply Chain of Bechu APP: Byteampraya SDocument9 pagesAnalyzing The Supply Chain of Bechu APP: Byteampraya SHarsh Singhal 4-Year B.Tech. Chemical EngineeringNo ratings yet

- B.B.M. - IB - SyllabusDocument23 pagesB.B.M. - IB - SyllabusNeeraj BagadeNo ratings yet

- "Demat Account": Project Report Submitted Towards Partial Fulfilment of PGDMDocument58 pages"Demat Account": Project Report Submitted Towards Partial Fulfilment of PGDMAnuraaag67% (3)

- SAPmodules BriefingDocument8 pagesSAPmodules BriefingAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Chander MohanDocument8 pagesChander Mohanron thakurNo ratings yet

- AR Fascinate Shelters Pvt. LTDDocument8 pagesAR Fascinate Shelters Pvt. LTDRAmNo ratings yet

- Synopsis RecruitmentDocument5 pagesSynopsis Recruitmentmanepally.kiranNo ratings yet

- Far 2 - AssignmentDocument3 pagesFar 2 - AssignmentAikal HakimNo ratings yet

- Vibhava ChemicalsDocument17 pagesVibhava ChemicalsPriyansh MehrotraNo ratings yet

- UAE New ListDocument18 pagesUAE New ListForline Fernando100% (1)

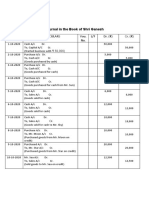

- Journal in The Book of Shri Ganesh: Date Particulars Vou. No. L/F Dr. Cr.Document4 pagesJournal in The Book of Shri Ganesh: Date Particulars Vou. No. L/F Dr. Cr.Anuj GohainNo ratings yet

Success Formulas For Shopping Centres in Romania

Success Formulas For Shopping Centres in Romania

Uploaded by

Raul VasvariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Success Formulas For Shopping Centres in Romania

Success Formulas For Shopping Centres in Romania

Uploaded by

Raul VasvariCopyright:

Available Formats

Success Formulas for

Shopping Centres

in Romania

Performance infuencing variables

www.pwc.com/ro

04

Executive Summary

10

Romanias Shopping Centre Market

06

Economic Context

22

Evaluation of Shopping Centres

and Defnition of Formulas for Success

Contents

PwC and Sonae Sierra |4

Rapid pre-crisis growth propelled

Romania into one of the fastest

growing economies in Europe,

which spurred high local and

foreign investment in a number

of industries, including retail.

However, the economic crisis coupled

with austerity measures taken by

the government in recent years have

had a signifcant negative impact on

Romanias business environment with

noticeable drops in the countrys GDP,

employment and income. 2011 marked

a return of moderate growth despite

lingering economic uncertainty.

Modern retail growth in Romania was

driven by higher demand due to change

in lifestyle, rising discretionary income

and higher indebtedness of customers.

Consequently, retailers expansion plans

resulted in a rapid increase of the

countrys GLA (Gross Lettable Area)

hinging on a high demand for

commercial space. In 2012-2013,

Romania is expected to extend its now

existing GLA , but the shopping centre

penetration will still lag far behind the

European average. Romanias modern

retail space is likely to further expand

hand in hand with the recovery from the

global economic and fnancial situation.

The GDP and GLA indicators are strongly

correlated in Europe. Countries with

higher GDP per capita show a higher

shopping centre penetration. The same

correlation is visible in Romania, too.

Most of the modern retail space is

located in Bucharest and other major

cities with high retail penetration and

above country average salaries, while

some counties/cities with lower income

level are noticeably underdeveloped in

terms of retail space.

Overall, small sized shopping centres are

the most numerous, large and very large

centres are mainly concentrated in

Bucharest. Shopping centres with a low

complexity, i.e. neighbourhood and

community centres, represent around

50% of the total number. Regional or

super-regional centres are located in

larger cities, mainly Bucharest. Recently

there has been a notable rise of power

centres, i.e. shopping centres that use

several high profle anchor tenants as

their main attraction.

Shopping centre development was

driven by a shortage of (modern) retail

space. The result was a fragmented

market. Out of 40 top-ranking

shopping centres analysed, 5 account

for approximately 38% of the total

turnover, but only for 21% of the GLA.

Moreover, competition has been

historically low, ensuring fnancial

success in most cases, despite a

relatively low focus on relevant success

criteria such as location, accessibility

for all means of transport, tenant mix,

management experience, catering and

leisure components or marketing.

However, our study shows that the best

performing shopping centres visibly

outperform the average score on all

analysed criteria. Smaller centres tend

to perform better for criteria such as

location and access for various means

of transport, but lack a wide selection

of catering and leisure options. Larger

ones perform better at the latter set of

criteria and they tend to have a more

diverse assortment mix, but show less

accessibility for various means

of transport.

The main success criteria resulting

from our analysis is professionalism

of the shopping centre management.

Historically, the management of most

centres focused on administrative

activities and revealed a convenient

and inexpensive approach, but as

competition intensifes and customers

are expected to become more demanding,

a professional approach to management

will become increasingly important. Since

professional management is deemed the

main success criterion, it is important to

understand how to defne it.

Executive Summary

5| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

A professional management team

does not only care about collection,

accounting and proper operation, i.e.

security, cleaning, proper functioning

and maintenance of the technical

equipment, managing the marketing,

internet presence, PR, etc. On top of

these everyday tasks, professional

management is about supervising and

proactively managing the performance

of the business clients, i.e. tenants as

well as customers. In order to do so,

customers background, purchase power

and purchase behaviour need regular

examination, each tenants assortment

of goods and performance in comparison

to another need permanent and steady

monitoring, meaning that the targets

for marketing and/or tenant mix must

be pro-actively managed. A signifcant

trend will be the shift towards

experienced, professional managers

who can add value in terms of tailored

leasing contracts, tenant mix and the

creation of a strong shopping-centre

identity, shaping a destination and

atmosphere customers will long for

and enjoy.

Similarly, aspects such as character

and identity are expected to become

crucial in future retail developments,

with shopping centres becoming

increasingly complex. Shopping centre

management is expected to be

responsible for this change.

Moreover, evolving customer demand

and behaviour will increase the

importance of previously neglected

criteria such as appealing design

(exterior as well as interior), adequate

and user friendly parking space, quality

of public spaces, shopping centre layout

and ease of navigation in the shopping

centre. While new shopping centres can

beneft from this trend, it will be a

much stronger challenge to revitalize

existing shopping centres in order to

ensure their success in the medium

and long term.

PwC and Sonae Sierra |6

The rapid pace of the pre-crisis

growth turned Romania into one

of the fastest growing economies in

Europe and attracted increasing

levels of foreign investment in

many branches of the economy.

Retail was one of the sectors that

benefted most from both foreign and

local investment. This was driven by

rising demand, in its turn sustained by

the diversifcation of customer needs

and behaviours, a rise in discretionary

income due to higher wages and the

high amount of private loans

contracted by consumers.

The economic crisis had signifcant

negative effects on the Romanian

business environment. One of the

underlying growth drivers before

the crisis was excessive consumption

sustained by consumer loans; with

the credit crunch, consumption fell

abruptly. Such an effect, compounded

by the economic impact of the austerity

measures taken by the government

in 2010 and 2011, cascaded into a

noticeable economic decline in

recent years.

Chart 1. Romanian GDP per capita in 2010 and GDP evolution (bn. EUR, %, EUR/capita)

959

799

769

502

439

328

204

101

Moldova

Ukraine

Bulgaria

Romania

Russia

Poland

Hungary

Czech Rep.

416

509

436 439

468

500

535

573

613

+5%

2015f 2014f 2013f 2012f 2011e 2010 2009 2008 2007

Gross average monthly salary in Romania (EUR) Gross average monthly salary benchmark (EUR)

2013f

121.8

3.4 %

2012f

120.7

2.1 %

2011e

119.0

1.7 %

2010

116.2

-1.6 %

2009

130.6

-6.6 %

2008

133.9

2010 2009 2008

7.3 %

EU - 27 average 24.40

Ukraine 2.18

Bulgaria 4.80

Romania 5.80

Poland 9.27

Hungary 9.70

Czech Rep. 14.20

Slovenia 17.30

Italy 25.70

UK 27.40

Germany 30.30

GDP/Capita benchmark (thousand EUR) Romanias GDP at market prices and year-to-year

real GDP evolution (bn. EUR, %)

101

204

328

439

502

769

799

959

Hungary

Czech Rep.

Moldova

Ukraine

Bulgaria

Romania

Russia

Poland

Net average monthly salary in Romania and real growth rate (EUR) Gross average monthly salary benchmark (EUR)

419.4

399.3

380.6

361.5

348.6

330.4

321.2

355.4

2015f 2013f

1.6% 1.8%

2014f

1.4%

2012f

1.2%

2011e

0.5%

2010

-3.7%

2009

-1.5%

2008

16.5%

133.9 130.6

116.2

127.1

136.0

146.1

157.2

169.3

4.2%

2012f

7.3%

2011

-6.6%

2010

-1.6%

2009

2.5%

2008

1.7%

2014f

3.5%

2015f

4.4%

2013f

EU-27 avg. 24,8

Bulgaria 4,9

Romania 6,3

Poland 9,7

Hungary 9,9

Czech Rep. 14,4

Slovenia 17,2

Italy 25,7

UK 26,3

Germany 31,2

GDP/Capita benchmark in 2011 (thousand EUR)

Romanias GDP at market prices and year-to-year

real GDP growth (bn. EUR, %)

Economic Context

Source: Eurostat, CNP, PwC analysis

7| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

Chart 2. Gross monthly salary in Romania and in selected SEE countries (EUR)

959

799

769

502

439

328

204

101

Moldova

Ukraine

Bulgaria

Romania

Russia

Poland

Hungary

Czech Rep.

416

509

436 439

468

500

535

573

613

+5%

2015f 2014f 2013f 2012f 2011e 2010 2009 2008 2007

Gross average monthly salary in Romania (EUR) Gross average monthly salary benchmark (EUR)

2013f

121.8

3.4 %

2012f

120.7

2.1 %

2011e

119.0

1.7 %

2010

116.2

-1.6 %

2009

130.6

-6.6 %

2008

133.9

7.3 %

EU - 27 average 24.40

Ukraine 2.18

Bulgaria 4.80

Romania 5.80

Poland 9.27

Hungary 9.70

Czech Rep. 14.20

Slovenia 17.30

Italy 25.70

UK 27.40

Germany 30.30

GDP/Capita benchmark (thousand EUR) Romanias GDP at market prices and year-to-year

real GDP evolution (bn. EUR, %)

169.3

157 .2

146.1

144.5

135.8

123.3

119.0 121.5

4.2%

2012f

7.3%

2011e

-6.6%

2010

-1.6%

2009

2.5%

2008

1.7%

2014f

3.5%

2015f

4.4%

2013f

EU- 27 avg. 24,8

Bulgaria 4,9

Romania 6,3

Poland 9,7

Hungary 9,9

Czech Rep. 14,4

Slovenia 17,2

Italy 25,7

UK 26,3

Germany 31,2

GDP/Capita benchmark in 2011 (thousand EUR) Romanias GDP at market prices and year-to-year

real GDP growth (bn. EUR, %)

101

204

328

439

502

769

799

959

Hungary

Czech Rep.

Moldova

Ukraine

Bulgaria

Romania

Russia

Poland

Net average monthly salary in Romania and real growth rate (EUR) Gross average monthly salary benchmark (EUR)

419.4

399.3

380.6

361.5

348.6

330.4

321.2

355.4

2015f 2013f

1.6% 1.8%

2014f

1.4%

2012f

1.2%

2011e

0.5%

2010

-3.7%

2009

-1.5%

2008

16.5%

Romanias GDP dropped by 6.6% in 2009

and by 1.6% in 2010. However, 2011

marked a return to growth, despite

persisting economic uncertainty due

to the emerging sovereign debt crisis

in the Euro area.

Although Romanias GDP/capita is slightly

higher than in some of the neighbouring

countries, like Ukraine and Bulgaria,

it still lags signifcantly behind the EU

average and more importantly, behind

many other countries in the CEE area,

such as Poland, Hungary and the

Czech Republic.

Employment conditions also underwent

a diffcult period, with unemployment

rising to double digit levels in some

areas. The harsher market conditions

in the private sector correlated with cuts

in the public sector wages caused average

Romanian wages to drop under the

2009 levels, and are not expected to

surpass pre-crisis levels until this year.

The same as GDP/capita, average salaries

in Romania are low, compared to most

CEE countries, but surpass Bulgaria and

Romanias non-EU member neighbours.

Source: National Bank of Romania, National Statistics Institute, CNP, PwC analysis and estimates

PwC and Sonae Sierra |8

The Romanian consumer spending

per capita is signifcantly lower than

the EU-27 average and than most CEE

countries, indicating a strong potential

for further growth in the following

years, as we emerge out of the crisis.

Household consumption in Romania has

a skewed structure with food and

non-alcoholic beverages accounting for

43% of total consumption, compared to

only 13% the EU average.

The structure is explained mostly

by low income levels and is likely to

change as wages grow, with a higher

share allocated to entertainment,

catering, hotels, clothing and footwear

expenditure.

Chart 3. Consumer spending dynamics in selected CEE countries (thousand EUR, %)

Chart 4. Household expenditure type and consumption structure (%)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

C

o

n

s

u

m

e

r

s

p

e

n

d

/

c

a

p

i

t

a

(

2

0

1

0

,

i

n

t

h

o

u

s

a

n

d

E

U

R

)

24

22

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

CAGR consumer spend (2004-2012)

Croatia

Serbia

Russia

Kazahstan

Ukraine

Belarus

Romania

Turkey

Macedonia

Slovakia

Slovenia

Poland

Hungary

Lithuania

Latvia

Estonia

Czech

Republic

Bulgaria

European Union (27 countries)

Consumer spend per capita (thousand EUR)

15%

24%

13%

6%

5%

5%

11%

9%

9%

Education

Healthcare

Other

Restaurants and hotels

Recreation and culture

EU-27

Alcoholic beverages & tobacco

Clothing and footwear

6%

5%

4%

1%

Romania

43%

8%

5%

4%

4%

3%

1%

1%

Food and non-alcoholic beverages

Housing, water, electricity & fuels

Communications

Transportation

Furnishings, household equipment

13%

3%

4%

3%

16%

10%

Taxes and contributions

Other

Investment

Household

production

1%

Consumption

70%

Note: CAGR consumer spend, or the Compound Annual Growth Rate for consumer spending is

the year-to-year growth rate of the consumer spending over the specied time period.

Source: World Bank, Eurostat, PwC analysis and estimates

Source: National Institute of Statistics, Eurostat, PwC analysis and estimates

9| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

Chart 6. Consumer and retail condence index in EU and Romania

Mirroring consumption trends, the

Romanian retail turnover recorded an

important contraction after 2008 but

stabilized in 2011. However, both food

retail and non-food retail continued to

show higher growth rates than the EU

average after 2007. Non-food retail

industry grew at a faster pace,

indicating changing consumer habits

and proving the potential for further

growth of this retail segment.

Food retailers were the frst to come to

Romania, while other segments started

their expansion later. The crisis changed

retail in two respects. First, many poorly

adapted and unstructured local retailers

and franchisees with only a few shops

disappeared from the market, due to

lack of effcient operational and

strategic business, which placed

surviving retailers in a favourable

competitive position.

Even with a reduced market potential

due to the decreased purchase power,

retailers streamlined over-proportional

business models, which left a higher

share to those of them who survived.

Secondly, international retail chains

started entering Romania directly

and no longer by franchising business

models. However, retail shows a positive

dynamic and, as mentioned above, it

represents a business area with strong

potential for growth.

Although Romanian consumers are

currently pessimistic, even more so than

in other countries, most retail segments

show a potential for growth in the

medium term. That is why retailers still

invest in expansion, taking advantage of

the relative low investment costs and,

probably more important, of the overall

reduced rent for retail spaces. While

results may be under pressure in the

short term, they are expected to improve

with the recovery of the economy in the

medium and long term.

Chart 5. Evolution of retails basic breakdown in Romania as compared to the EU average

(2005=100, seasonally adjusted series)

0

RO - retail of non-food

RO - retail of food

RO - total retail

EU 27 - total retail

110

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

200

190

180

170

160

150

140

130

120

1.7.11 1.1.11 1.7.10 1.1.10 1.7.09 1.1.09 1.7.08 1.1.08 1.7.07 1.1.07 1.7.06 1.1.06 1.7.05 1.1.05

RO - Consumer

1.1.12

RO - Retail

EU - Retail

EU - Consumer

Source: National Institute of Statistics, Eurostat, PwC analysis and estimates

Source: National Institute of Statistics, Eurostat, PwC analysis and estimates

PwC and Sonae Sierra |10

By size, shopping centres were

segmented into:

Small size commercial spaces are

centres with a GLA of less than

20,000 sqm;

Medium size commercial centres

have a total GLA between 20,000

and 40,000 sqm;

Large size centres have between

40,000 and 80,000 sqm;

Very large size shopping centres

have a GLA of more than 80,000 sqm.

Romanias Shopping Centre Market

In segmenting Romanian

and regional shopping

centre markets, the analysed

centres were grouped together

by two main factors: size,

expressed in total GLA

and type, under the ICSC

(International Council

of Shopping Centres)

classifcation.

Analysis Methodology

In order to assess the shopping

centres market in Romania we

developed a methodology based

on five main criteria:

Market environment, including key

demographics and concentration

or polarisation of competition in

the catchment area of the analysed

shopping centres;

Location in the host city and ease

of access for customers;

Operational effectiveness, driven by

the GLA utilisation, number and

diversity of tenants, quality of service,

entertainment and food courts;

Financial Performance, measured

through key indicators such as turnover

and revenue per square metre;

Management and marketing,

according to the defnition set in

the executive summary at page 4.

11| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

Romanias Shopping Centre Market

For each commercial centre analysed, we assessed and ranked centres based

on a range of criteria for success. The six key criteria for success are:

1. Location in the host city;

2. Access and easy reach for customers, measured by transport time,

transportation options and costs, etc.;

3. Assortment and tenant mix based on the diversity and quality of

anchors and merchants;

4. Catering and leisure based on the availably, quality and diversity

of entertainment and leisure options in the shopping centre;

5. Professionalism of centres management driven by the success of the

management team to improve operational effciency and maintenance,

marketing, commercialization and legal management of centres needs;

6. Marketing and online presence measured by the level of marketing

activities, both direct and indirect and by the centres presence on various

media channels, particularly online.

Each individual shopping centre in our sample was scored on a scale from 1 to 5

for each key criterion for success, where 1 represents poor performance and 5

represents very good performance on the relevant criterion (e.g. 1 - very poor

location, 5 - very good location).

The resulting scores were subsequently used to identify correlations between

each key criterion for success and the overall success of a shopping centre

(measured in terms of revenue).

By type, shopping centres were split into:

Neighbourhood centres are designed

to provide convenience shopping

for the daily needs of consumers

living in their immediate vicinity

or neighbouring areas. Most of them

are anchored by a supermarket or

a pharmacy.

Community centres refer to those

centres offering a wider range of

commodities (including clothing

and other goods) than neighbourhood

centres, which might also include

off-price retailers and a wider variety

or anchors.

Regional centres provide general

merchandise and services in full

depth and variety. Moreover, their

main point of attraction is given by

their anchors: traditional, mass

merchant, discount department stores

or fashion speciality stores.

Super-regional centres are relatively

similar to regional, but due to their

larger size, they have more anchors,

higher merchandise diversity and

they address a larger customer base.

Power centres refer to centres

dominated by a number of large

anchors, including discount and

off-price stores, warehouse clubs

and others. Such a centre typically

consists of several unconnected

anchors and only a minimum

amount of small speciality tenants.

PwC and Sonae Sierra |12

The signifcant increase in total

shopping space development in

Europe after 2005 was almost

entirely driven by strong increases

in fast growing economies in CEE

and Turkey.

After reaching a peak in 2008, new

shopping space delivered in Europe fell

sharply in 2009 and 2010 on account

of the decline of retail space demand,

caused by a mix of reduced consumer

demand and a shortage of available

bank fnancing (mostly due to tighter

banking regulations in all countries.

Still, statistics show a more favourable

development for the coming years, with

new investments expected in CEE and

especially in Turkey.

Romania ranks 12th in Europe in terms

of expected growth of retail space, but

only 27

th

in terms of available shopping

centre space per 1,000 inhabitants, which

refects a still very low degree of modern

shopping centre space penetration.

Shopping Centre Development in

Romania and the European Context

Chart 7. New shopping centre space in Europe between 1990 and 2012 (million sqm)

+8%

2

0

0

7

8.1

2

0

0

6

8.0

2

0

0

5

6.1

2

0

0

4

4.2

2

0

0

3

5.1

2

0

0

2

4.0

Western Europe

CEE

and Turkey

2

0

1

2

e

5.7

2

0

1

1

e

6.8

2

0

1

0

5.4

2

0

0

9

7.5

2

0

0

8

9.5

2

0

0

1

3.8

2

0

0

0

4.3

1

9

9

9

3.9

1

9

9

8

3.5

1

9

9

7

2.7

1

9

9

6

2.6

1

9

9

5

3.4

1

9

9

4

2.7

1

9

9

3

3.1

1

9

9

2

2.3

1

9

9

1

2.3

1

9

9

0

2.5

-12%

Source: Crushman & Wakeeld, PwC analysis

13| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

Chart 8. Estimated European shopping centre pipeline 2011/2012 (million sqm)

Romania ranks 7th in Europe in terms of new shopping

centre space delivered in 2011/2012. Russia leads the

European countries with regard to the estimated shopping

centre development pipeline, showing slightly less than

double of the surface of the runner-up, Turkey which, in its

turn accounts for almost double of the second runner-up,

Italy. Russia and Turkey together represent almost 40%

of the pipeline, whereas Central and Eastern Europe is

estimated to sum up approx. 63% of new shopping centre

space in the 2011 - 2012 timeframe.

0.0

Switzerland

Estonia

Latvia

Finland

0.0

Bosnia Herz

Danemark 0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

Belgium 0.0

Lithuania 0.1

Serbia 0.1

Grecee

Luxembourg

Spain 0.7

France 0.9

Italy 1.0

0.6 Poland

0.3 UK

0.3 Germany

0.3 Croatia

0.3

0.3

Russia

Portugal

3.1

Romania

0.2

0.3

Czech Rep.

Ukraine

0.3

0.3 Netherlands

Turkey 1.8

0.1

Norway 0.1

Ireland 0.1

Bulgaria 0.2

Sweden 0.2

Hungary 0.2

Austria 0.2

Slovenia 0.2

Slovakia

Source: Romanian Business Digest, Crushman & Wakeeld, PwC analysis and estimates

PwC and Sonae Sierra |14

Chart 9. GLA allocation in selected CEE countries (% of national GLA)

Shopping centre GLA in CEE increased

by approximately 50% in the last three

years, reaching a total surface of

approximately 12 million sqm at the end

of 2010. Although impressive, growth

levels could have been even higher if the

global fnancial crisis had not limited

the developers expansion plans and

signifcantly pressured customer

purchasing power and confdence.

Poland has the highest GLA in CEE,

but the pipeline in other countries is

expected to change the allocation of the

GLA in this region. The GLA increased

rapidly in Romania, up to the second

largest GLA in the region, very close

to the Czech Republic. Although it is

diffcult to make a forecast, the GLA

in Romania is likely to grow faster than

in most of the other CEE countries.

Hungary

Czech Rep.

Poland

Romania

Slovakia

Bulgaria

2013f

100%

45%

13%

10%

18%

7%

7%

2010

100%

44%

16%

12%

16%

7%

5%

2007

100%

50%

18%

15%

9%

6%

2%

Source: PMR publications, Shopping Centres in Central Europe 2011

15| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

In most European countries, there is an

apparent correlation between economic

development and shopping centre space.

The population in countries with high

GDP per capita have a higher level of

discretionary income and a more diverse

spending structure, which results in a

more developed retail market than in

countries with lower GDP per capita.

The study shows that even at the current

GDP level, the GLA per capita is somewhat

lower in Romania than it should be; the

overall medium and long-term potential

is even bigger, because of the expected

gradual alignment of its GDP with peer

countries.

An important aspect for the development

of shopping centres is the level of rental

income, which varies between different

retail types, predominantly high street

locations and shopping centres.

The difference between the two types

can vary signifcantly from one country

to another, or even between cities.

While generally in Central and Eastern

Europe rental cost is higher in high-street

locations, shopping centre prime rent

levels in Bucharest are close to rent for

high prime street spaces. Two reasons

might have infuenced this development:

frst, the high demand for shopping

centres space in recent years and second,

the signifcantly lower quality of

available high-street space combined

with a very unattractive and customer

unfriendly high-street itself.

Chart 10. Correlation between GDP/capita and shopping centre GLA (sqm/1000 inhabitants, EUR/capita)

Chart 11. Main rental levels in selected CEE countries in Q3 2011 (EUR/sqm/month)

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

550

600

650

700

80.000 70.000 60.000 50.000 40.000 30.000 20.000 10.000 0

Ukraine

Bulgaria

Turkey

Russia

Romania

Belgium

GDP/capita (EUR)

Consolidating

markets

Mature markets

New & expanding markets

G

L

A

(

s

q

m

)

/

1

0

0

0

i

n

h

a

b

i

t

a

n

t

s

Spain

France

UK

Portugal

Finland

Denmark

Austria

Netherlands

Estonia Luxembourg Ireland

Sweden

Norway

EU-27 Average

Germany

Italy

Slovenia

Czech Rep.

Lithuania

Latvia

Malta

Hungary

Croatia

Greece

Poland

Slovakia

65

55

Romania

50

24

Bulgaria

65

170

Czech

Republic

35

92

Serbia

High Street Prime Rents

Shopping Centers Rents

85

Poland

78

100

Hungary

90

75

Croatia

32

Source: Eurostat, PwC analysis

Source: Cushman & Wakeeld, European Retail Report, November 2011

PwC and Sonae Sierra |16

Evolution of Romanian Retail Stock

Chart 12. Evolution of the Romanian shopping centre GLA (thousand sqm)

2009

Added space (1000 sqm)

Total existing space (1000 sqm)

292

37 55

24

55 64

114

87

233

741

217

324

767

330

384

408

462

526

640

727

<1990 2011

1.701

2008 2007

1.918

2.243

2004 2000 1999

3.010

2010 2006

960

2003 2002 2005

Source: PwC analysis, Press releases

Since its transition from a

state-controlled economy

to a free market economy,

Romania developed into one

of the most active emerging

markets, attracting foreign

investors especially through

its dynamic retail segment.

The frst modern retail space was

opened in Bucharest in 1999 and

since then the pace of development

has been fast, reaching more than

1.7 million sqm in 2008.

Despite the slowdown of retail

caused by the economic crisis,

shopping centre GLA continued to

grow at an increasing annual rate,

reaching an estimated 3 million

sqm in 2011. Most of these new

openings started development and

secured fnancing before the crisis,

but the pipeline for 2012-2013

remains strong.

17| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

The largest share of modern retail space

in Romania is located in Bucharest. Such

an unbalanced geographical spread is

mainly caused by the gap in economic

development between Romanian regions.

Due to higher income levels and more

sophisticated customer behaviour, as

well as an important population,

Bucharest is currently the largest

market for modern retail.

Chart 13. Distribution of Romanian modern retail stock (% of GLA)

9%

8%

8%

6%

4%

South West

Center

South East

West

North West

North East

14%

South 53%

8%

Bucharest

92%

Rest of

Southern Region

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates, Press release

PwC and Sonae Sierra |18

Romanian shopping centres are

predominantly small sized. Large

and very large sized ones are located

in Bucharest and in a few other large

cities. Small size shopping centres

prevail in the rest of the country.

The relatively few very large sized

shopping centres sum up 27% of total

GLA, almost as much as the more

numerous small sized ones.

Neighbourhood and community

centres account for approximately

50% of the total GLA, having a

wider geographical spread than

regional and superregional centres.

However, the number of power

centres (16% of the national GLA

spread over all regions of the

country) rose in recent years.

Chart 15. Distribution of GLA per type of commercial centre (%)

23%

17%

16%

16%

Super-regional Centre

Regional Centre

Community Centre

Neighbourhood Centre

27%

Power Centre

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates, Press releases

Chart 14. Distribution of GLA per type of commercial centre (sqm)

Small size

Medium size

Large size

Very large size

GLA per segment of commercial centre

100%

32%

21%

20%

27%

No. of commercial centres

by size segmentation (%)

100%

65%

18%

13%

4%

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates, Press release

Neighbourhood and

community centres

represent approximately

50% of the total Gross

Lettable Area.

19| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

Chart 16. Regional breakdown of GLA to GDP ratio (sqm/1000 inhabitants, EUR/capita)

G

L

A

(

s

q

m

)

/

1

0

0

0

i

n

h

a

b

i

t

a

n

t

s

600

550

500

450

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

GDP/capita (EUR)

16.000 14.000 12.000 10.000 8.000 6.000 4.000 2.000 0

VN

VS

VL

TL

TM

TR

SV

SB

SM

PH

OT

NT

MS

MH

MM

IF + B

IS

IL

HD

GL

DJ

CT

CJ

BZ

BV

BR

BT

BN

BH

BC

AG

AR

AB

Above average

Below average

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates

On a regional level, counties with a higher

GDP per capita show higher retail space per

capita. Bucharest stands out with the highest

GDP (>15,000 EUR per capita) and the highest

GLA (560 sqm per capita). Quite remarkable,

since Timisoara, the second richest town in

Romania, has 60% of Bucharests GDP per

capita, but only 22% of Bucharests GLA per

capita. Arad is the runner-up in terms of GLA

per capita. Compared to Bucharest, Arads

characteristics are rather balanced and evince

approximately 45% of Bucharests GLA and

GDP level. There are some counties with very

few or no shopping centres, such as Calarasi,

Dambovita, Harghita and Salaj.

PwC and Sonae Sierra |20

From a size perspective, very large size

commercial spaces are found almost

exclusively in Bucharest, while in all

other areas small size commercial

spaces are predominant. For example,

in the Central region of the country

small size spaces account for around

94% of the total GLA and in the South

West approximately 88%. Medium size

commercial spaces are more dispersed

geographically, but have the highest

proportion in Bucharest and the South

Eastern regions. Large size centres are

more common in Bucharest and the

Western area. The existing disparities

in the geographical distribution of

shopping centre space indicate that

some areas are underdeveloped, while

others show a high level of shopping

centre penetration.

An important condition for success for

future shopping centre projects will be

to identify and target those areas with

high or medium potential in terms of

revenues (i.e. high density and/or high

purchase power) but with low shopping

centre space. The detailed analysis

of the catchment areas will also call

for adaptations in terms of shopping

centre size, since small and medium

sizes are most likely to proliferate over

the next period. Large and very large

size shopping centres will remain

confned to Romanias largest cities.

Chart 17. Distribution of commercial space per region, by size (%)

0%

12%

17%

20%

35%

33%

20%

6%

12%

17%

10%

20%

8%

13%

20%

0%

20%

0%

Small size

Medium size

Large size

Very large size

West

60%

0%

South West

88%

0%

0%

South East

58%

Bucharest

25%

South

70%

0%

North West

67%

0%

North East

77%

0%

Center

94%

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates

21| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

The distribution of the main shopping

centre types is more balanced.

Neighbourhood and community centres

are predominant in most regions, with

the exception of the Southern area,

where Bucharest with its superregional

and regional centres distorts the picture.

That is in no way surprising because

Bucharest has 4 times as many

inhabitants as the 2

nd

largest city

and thus, cries for superregional

attractiveness.

In recent years, power centres have

spread across all regions. Due to a

number of key developments in

Bucharest and in other cities, such as

Constanta, Pitesti and Braila, power

centres are currently slightly better

represented in the South East and South.

Up to 2008, the development of new

shopping centres in Romania was

increasingly seen as a favourable

business opportunity by both local and

foreign investors. Investment funds,

for example, showed massive interest

in pursuing new projects not just in

Bucharest, but also in other areas

of the country, with less coverage

in terms of shopping centre space.

From 2009 until 2011, there were

completed mainly those developments

that secured fnancing before the crisis

started. After the effects of the crisis

began to be felt in Romania, construction

works started for only a few new

shopping centre developments

(predominantly those developments

done by hypermarkets or based on a

forward purchase with a hypermarket).

It is the belief of the authors that the

crisis has had and will continue to have

a long-lasting infuence on the real

estate business. Due to the changes in

banking regulations, long term

investment loans will be limited to 50

to 60 % of the investment value, i.e.

the developer and investors will need to

contribute 40 to 50% of the investment

value by equity. Commercial real estate

faces a 400 to 700 bn fnancing gap,

mainly from bank deleveraging

1

.

This will have long term and signifcant

impact on the developers and tenants

strategies. Real estate investors will be

much more selective and will prefer high

quality projects in dominant locations,

which ensures the sustainability of

future income and value.

Chart 18. Distribution of commercial space per region, by type (%)

6%

15%

25%

29%

8%

20%

19%

12%

18%

33%

14%

20%

25%

31%

17%

14%

25%

29%

30%

25%

31%

50%

18%

25%

29%

20%

North West

8%

North East

12%

Center

25%

Community Center

Neighborhood Centre

West

10%

South West

29%

South East

8%

South

21%

Superregional Center

Regional Center

Power Center

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates

1

Banks Deleveraging and Real Estate, Morgan Stanley Blue

Paper, 15th March 2012

PwC and Sonae Sierra |22

The study of the 40 top-ranking

shopping centres shows that the

top 5 shopping centres account

for around 38% of total revenues

altogether, but only for 21% of

total GLA.

It is interesting to note that some shopping

centres show relatively low turnover while

having high revenues per sqm. That could

be explained by a variety of reasons, such

as the tenant mix or higher revenues from

secondary sources. On the other hand,

some high- ranking shopping centres have

relatively low revenues per sqm despite

high overall turnover.

Chart 19. Shopping Centres snapshot: turnover vs. GLA (mil. EUR, %)

Evaluation of Shopping

Centres and Definition

of Formulas for Success

GLA (000 sqm)

T

u

r

n

o

v

e

r

(

E

U

R

m

i

l

.

)

Top 5 centres

account for:

38% of revenue

21% of GLA

Next 15 centres

account for:

35% of revenue

35% of GLA

Bottom 25 centres

account for:

27% of revenue

44% of GLA

Revenues per GLA (EUR/sqm)

90

10

0

5

35

25

15

30

15 0 30

20

45 75 60

30

35

25

Top 5 centres by revenues per GLA

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates

23| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

The top 40 shopping centres in terms

of turnover are mostly represented by

small or medium sized centres, with

a limited number of top performers

recording very high revenues.

Chart 20. Shopping Centres snapshot: size vs. revenue per sqm (EUR/sqm, GLA in sqm)

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

550

600

Small

size

Medium

size

Large

size

Very large

size

Best in

class

Above

average

Below

average

EUR/sqm

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates

PwC and Sonae Sierra |24

The shopping centre market in Romania

is still in an opening phase, far from

the mature markets, like the US or

Western Europe. Shopping centre

development has been driven by the lack

of or low penetration of modern retail

space and resulted in a fragmented

market. Competition levels have been

historically low, facilitating fnancial

success in most cases. Developers paid

little attention to quality criteria such as

assortment mix, parking space, design,

layout or overall customer friendly

environment. The perspective for high

and quick developer margins motivated

inexperienced investors with the

consequence that some centres perform

quite badly.

However, with the increase in competition,

the effects of the economic crisis and the

advent of more selective and demanding

customers, shopping centre operators

will fnd it increasingly hard to attract

revenues without focusing on the key

success drivers.

As described in our chapter Analysis

Methodology, for each shopping

centre in our sample we measured the

extent to which the identifed success

factors are addressed, by attributing

each of them a score from 1 to 5.

As shown in chart 21, there is a high

level of correlation between the overall

score obtained by a shopping centre

on the factors of our analysis and the

shopping centre success, measured

in revenues per square metre.

Chart 21. Impact of qualitative factors on shopping centre performance

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

550

600

650

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5 5.0

R

e

v

e

n

u

e

/

s

q

m

Average qualitative factors (average of all scores)

Signicant degree of correlation

Source: PwC analysis, Sonae Sierra estimates

25| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

Chart 23. Comparative results for best in class shopping malls vs. aggregate average (score)

Location

Acces

Completeness

assortment and tenant

mix

Catering & Leisure

Professionalism of the

centre management

1

2

3

4

5

6

Scale: 0 (low) 5 (high)

Best in class score

Average total score

Marketing and

online presence

Source: PwC analysis

Chart 22. Impact of key-success factors on shopping centre performance

Rank Factor Impact Remarks

1

Professionalism of management

Strongest correlation with overall performance

2 Assortment and tenant mix Critical impact on nal results

3 Access Relevant aspect for a shopping centres success

4 Location in the city Important differentiating factor

5 Catering & leisure Slight impact on shopping centres overall results

6 Internet presence Relatively low inuence on nal performance

Source: PwC analysis

In-depth analysis reveals the

hierarchy of key success factors

in terms of their infuence on

shopping centre performance.

Chart 23 presents a comparison between

the average of the 5 best-in-class shopping

centres (in terms of revenue) and the

average of the entire shopping centre

sample, from the perspective of each

individual success factor.

The analysis shows that the decisive

criteria in differentiating best in class

from the average pool of shopping

centres are the existence of professional

management, the completeness and

diversity of the tenant mix as well as

marketing and online presence.

Shopping centre

development has

mostly been driven

by the low penetration

of modern retail space

and resulted in a

fragmented market.

PwC and Sonae Sierra |26

The average performance of the

reviewed shopping centres on each

key factor varies signifcantly in the

size segment. Small size centres

perform better at factors such as

access and location, while large and

very large ones offer better leisure

options as well as a more diverse

tenant mix.

These results should be viewed in the

light of location and access constraints.

Downtown shopping centres are

usually small, since space for large

buildings is usually not available in

downtown locations of Romanian

cities. Surface limits the diversity

of the tenant mix and in most cases,

such centres do not have a food court

or a cinema. However, they beneft

from a very convenient location and

easy reach by public transportation or

on foot, which ensures in turn higher

visitor rates. Locations further from

downtown show a high penetration

of work places, which justifes usually

high customer frequencies and

remarkable chance purchases.

Chart 24. Comparative results for shopping centres by size segments (score)

Small size

1

2

3

4

5

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

Medium size

1

2

3

4

5

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

Large size

1

2

3

4

5

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

Very large size

1

3

4

5

1

2

3

4

5

6

Scale: 0 (low) 5 (high)

1 Location

Access 2

Completeness assortment

and tenant mix

3

Catering & Leisure 4

Professionalism of the

shopping centre management

5

6 Marketing and online presence

Source: PwC analysis

27| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

At the other end of the spectrum,

large and very large shopping centres

are usually positioned on the outskirts

of the cities, i.e. those centres are

usually accessed by car and less by

public transportation.

The tenant mix in these shopping

centres is nevertheless much broader

than in their smaller counterparts and

in most of the cases they have strong

anchors - hypermarkets, specialized

DIY stores or furniture retailers -

which turn them into regional and

super-regional centres, or even power

centres, attracting shoppers from the

adjacent regions as well.

Community centres have a similar

score profle to super-regional shopping

centres, while neighbourhood centres

resemble regional centres.

Super-regional centres usually suffer

from a poor online presence. Power

centres also have a relatively uniform

score profle, although with lower

average scores than other categories,

and substantially lower scores on

location and access, which is plausible,

as their size usually requires locations

far away from the city centre.

In the past, most shopping centres

were designed as regional centres,

serving a wide area, as they had little

or no competition. However, the fast

development of shopping centres

resulted in a much more competitive

environment. Both existing and

planned shopping centres need

permanently to adapt to specifc local

aspects, mainly the customers

purchase profle and behaviour.

The customers profle defnes a

sustainable tenant mix and the level of

entertainment. For existing shopping

centres refurbishment, GLA downsizing

or upgrading options should be

investigated seriously once the centre

performance goes down.

Chart 25. Comparative results for shopping centres by types (score)

Scale: 0 (low) 5 (high)

1 Location

Access 2

Completeness assortment

and tenant mix

3

Professionalism of the

shopping centre management

5

Catering & Leisure 4

6 Marketing and online presence

Power centre

1

2

3 5

6

4

Super-regional centre

4

1

2

3

4

5

6

Regional centre

1

2

3 5

6

4

Neighbourhood centre

1

2

3 5

6

4

Community centre

1

2

3 5

6

4

Source: PwC analysis

Source: PwC analysis

PwC and Sonae Sierra |28

Professionalism of the shopping

centre management appears to

be closely connected to the success

of the centre, both directly and by

infuencing other relevant factors.

In many cases, shopping centre

management teams are focused on

ensuring that maximum space is rented

out, occupancy rates remain high and

operational tasks are fulflled. That is a

convenient and inexpensive approach

and the low degree of competition in

the Romanian shopping centre market

has placed until now little importance

on other, more complex functions of

the shopping centre management.

However, as the number of shopping

centres increases and customers

become more educated and demanding,

shopping centre management will need

to become more proactive in order to

ensure continued success. On top of

the everyday tasks, a professional

management team supervises and

proactively manages the performance

of its clients, i.e. tenants as well

as customers.

In order to do so, customer background,

purchase power and purchase behaviour

need regular examinations (visitor rates

as function of time, amongst others),

a tenants assortment of goods and

performance (the turnover, amongst

others) in comparison to the others need

permanent and steady monitoring,

which consequently implies that the

targets for marketing and/or tenant mix,

shopping centre size and attractiveness

must be pro-actively managed, and

aspects that need improvement have to

be identifed. Additionally, a professional

management team with an international

background can have a better negotiating

position with retailers and be able to

achieve synergies in marketing and staff

employment.

Furthermore, a professional management

team fnds and implements effective

additional sources of income that

complement the centres typology

and offer. Throughout this process,

the management team fne-tunes the

effciency level of its operation combined

with Mall Income solutions that can add

economic beneft to the asset.

In this light, a signifcant trend in the

Romanian shopping centre landscape

could be the shift from shopping centre

administration towards a category of

professional managers who can bring

valuable contributions in terms of

rental contract design, tenant mix

and the creation of a strong

shopping-centre identity.

Professionalism of Management

29| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

The assortment and tenant mix

of a shopping centre are essential

to ensuring long-term success

and are compulsory to defne

the personality of the shopping

centre that should be well linked

to its targeted catchment area.

Specialist literature defnes the tenant mix

as a variety of stores that work together

to enhance the centres performance and

operate successfully as individual

businesses.

2

As shown by our study, this

factor has the second strongest infuence

on the overall performance. Shopping

centres recording high revenues per sqm

also tend to have a large and more diverse

mix of tenants. That refects evolving

customer tastes and preferences, mirrors

the existing household consumption

structure (see Chart 4) and pinpoints an

area of high relevance for the future of

shopping centres in Romania.

Well performing shopping centres need

to pay increased attention to their tenant

mix as a main lever for improving

proftability by providing the optimum

services to the community in which they

are located. Tenant mix design thus

ideally mirrors the range of products,

services, catering and entertainment

that appeals to the population in the

catchment area of the shopping centre

and gives the answer to all aspects of the

customer demographics, preferences,

lifestyles and income. Ultimately, the

tenant mix defnes which customers will

visit the shopping centre, but besides

providing appeal, the selected tenant

mix has to offer products affordable for

its target customer base.

Each Shopping Centre has its own

catchment area with a specifc purchase

power. In case the GLA in one category

is oversized, retailers belonging to that

specifc category tend to cannibalize

each other. On the other hand, in case

the GLA for a category is undersized,

visitors tend to shift to other retail areas

outside the shopping centres. Thus, the

effective allocation of the tenant mix is

indirectly linked to the tasks of the

management team.

As competition tightens, the tenant mix

will become a tool in the hands of the

Romanian shopping centre managers

enabling them to create a specifc image

and to differentiate from other shopping

centres nearby.

The experience of more developed

markets shows that anchors play the

most important role in the positioning

of a shopping centre, and these are

usually large retailers operating at

national or even international level.

However, smaller, local independent

traders that target local niches and have

an offer adapted to specifc tastes can

also shape differentiation.

However, in adopting such a strategy,

shopping centre managers must take

into account the ability of such smaller

retailers to pay the usually higher rents

associated to prime shopping centre

space. That may in turn involve

tailoring rent agreements to specifc

tenants, in order to ensure a diverse mix

of merchandise. Ideally, a customer

fnds everything he needs in a right

tenant mix.

Similarly, targeting previously

undeveloped areas in Romania will be

conditioned not only by adaptation with

regard of shopping centre size but also

by striking the optimum tenant mix,

adapted to the local customer habits and

purchasing power. Another trend will

be related to the development of niche/

specialized shopping centres, which

have a strong focus on selected

customer profles.

Assortment and Tenant-mix

2

Greenspan J, Solving the tenant mix puzzle in your

shopping centre, Journal of Property Management, 1987

Small size shopping

centres fare better in

terms of ease of access of

customers and location.

PwC and Sonae Sierra |30

The location in the city and the

access to the shopping centre can

differentiate between a successful

and a less successful shopping

centre.

As expected, a critical factor for the

shopping centre performance is the ease

of access to the shopping centres, by

either car, public transportation or on

foot, which in turn is closely connected

to the shopping centres location.

The two are not synonymous and yet a

less attractive location (further from the

city centre) can still be easily accessible

(proximity to a subway station, near a

large residential area). A shopping

centre scoring well on these two factors

performs better and an easy access

attracts customers with the logical

consequence of increased revenues.

As already mentioned, our study shows

that small size shopping centres fare

better in this respect than large or very

large schemes, which are in most cases

located on the boundary or outside the

city. Presumably, a disadvantage in

location overlaps substantially with

the infuence of existing or non-existing

competition. Lack of competition allows

suboptimal located shopping centres

to perform satisfactory. The same

infuence can be attributed to the

exclusive presence of some very few

but extremely appealing retailers.

The access and location of a shopping

centre is infuenced signifcantly by

whether suffcient parking space in a

user-friendly quality exists. In crowded

areas, such as Bucharest, the absence

or insuffcient provision of parking space

is a very signifcant factor that can deter

customers from visiting the shopping

centre. This infuence will become more

dominant with increasing competition.

Since it is usually very diffcult to improve

or enlarge existing parking facilities, the

number of lots and quality of parking are

essential design challenges.

Generally, large centres tend to sell

for the weekly demand, meaning that

customers buy large quantities in order

to satisfy a weekly demand. In such a

case, accessibility by car becomes more

important than public transport or

pedestrian access.

Finally, as the market matures,

positioning differentiation among

Romanian shopping centres will surge

and their targeted individual offer will

be shaped for a stronger dominance in

their catchment areas. In-town location

will position for upscale customer and

edge-of-town / out-of-town locations for

mainstream and quantity sales driven

shopping centres.

Access and Location in the City

The centre marketing approach

and its online presence can

contribute to better positioning

and proftability.

As shown in chart 26, there is a

signifcant correlation between the

marketing of a shopping centre and its

fnancial performance. It is a relationship

expected to play a growing role in an

increasingly competitive landscape. Even

if marketing activities are not proftable

in themselves, they increase the publicity

of a centre and inform the customer about

offers, new tenants, unique activities,

etc., thus they generate additional traffc

and increase the sales of shopping centre

tenants. It is the belief of the authors that

a good marketing strategy supports the

performance of a shopping centre.

Currently there is a signifcant gap in

terms of online presence between

best-in-class shopping centres and the

average shopping centres subject to our

study. For many Romanian shopping

centres, a complex website is not deemed

necessary at this moment, as competition

remains low and customers are likely to

visit the shopping centre regardless of its

online presence. However, well

performing shopping centres have

websites providing information on their

location, opening hours, parking spaces

as well as a list of retailers.

The World Wide Web has signifcantly

changed our day-to-day life in the last 10

years and it will change retail in the next

years. Internet retail gained a remarkable

market share in the past and will

undoubtedly continue to thrive. It is quite

diffcult to predict how this development

will change the face of shopping centres,

but some tendencies have become

apparent. For example, some shops might

witness a shift in their main purpose,

from a direct sales function to showrooms

and consultation and exhibition hubs.

Nevertheless, the existence of shopping

centres is not endangered by the internet;

there will always be a demand for going

shopping. The bigger shopping centre

owners are currently developing web

applications that promote and support the

attractiveness of the shopping centre in

cooperation with the larger tenants.

It can be argued that marketing is an

important tool in shopping centre

differentiation, especially in more

competitive areas, such as Bucharest and

other larger cities. Its importance has

grown over the recent period and will

most likely evolve further, with the

increase of competition. Furthermore,

the existence of a well-designed website

enhances visibility of a shopping centre

and can contribute directly to the number

of visitors, by offering detailed

information about the opening hours,

offer and facilities, promotions or themed

events organized by the management.

Marketing and online presence

31| Success Formulas for Shopping Centres in Romania

As expected, large and very large

schemes perform better than small

scheme shopping centres in respect

of catering and leisure. However, we

believe that this criterion should be

at the forefront of shopping centre

management concerns related to their

tenant mix.

Indeed, it can be argued that ever since

the development of the frst mall in the

1950s, entertainment has always been a

consistent part of it and today all

shopping centres strive to include

leisure and/or food amenities in their

mix. This is mostly due to the evolving

social function of the shopping mall,

from a functional destination to a

lifestyle centre, a space of

socialisation and entertainment.

Empirical studies have shown that the

presence of entertainment is closely

linked to the proftability of a shopping

centre and can improve other tenants

activities as well.

Such infuences can be proven; the

absence or existence of a cinema causes

a turnover variation in the food court,

of up to 20%, particularly in the

evening. Regardless of the motivation,

entertainment brings people to the mall

and thus increases proftability. Even

more, some people regard shopping

centres as a diversion from normal

day-to-day activities and are likely to

be attracted not only by entertainment

facilities, such as cinemas, bowling,

restaurants, ftness and spa centres,

event and show areas etc. but also by

the architecture, the interior design,

events, exhibitions and the atmosphere

in general.

Given the fact that entertainment

opportunities are currently quite limited

in most cities in Romania and are usually

represented by cinemas, the positioning

of the shopping centre as the local

entertainment hub is increasing in

importance and can represent a very

effcient strategy to attract customers.

Some of the most successful Romanian

shopping centres seek to provide

additional leisure opportunities

besides the traditional cinema, such

as ice-skating, gaming or bowling areas,

children playgrounds, etc. Having a

well-developed food court adds to the

overall shopping experience and

increases the time spent by customers

in the mall, the amount they spend

and their willingness to return.

The relevance of entertainment and

catering amenities will grow in the

future. The Romanian shopping centre

market is still in an early stage, and the

development of complex value creating

catering and leisure components has

been hindered so far by low income and

relatively less sophisticated customer

expectations. However, in the light of

future economic growth, customers

will begin to seek in a shopping centre

some value beyond the availability of

products and goods and will choose

shopping centres in relation to such

aspects. Therefore, one of the main

areas of relevance for shopping centre

managers is to shift their focus from

providing retail space to offering a

complete experience targeting all areas