Professional Documents

Culture Documents

On The Rainy River

On The Rainy River

Uploaded by

api-2527217560 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

205 views9 pagesOriginal Title

on the rainy river

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

205 views9 pagesOn The Rainy River

On The Rainy River

Uploaded by

api-252721756Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 9

T7 O N, I ODr J L TEXTS FOR WRI TERS

of bl ack Arneri cans ro sei ze l ocal enrrepreneuri al opport uni t i es i s co f ai l

to accept our rol e as l eacl ers of our own comrntrni ty. Not to dernand

thar each member of the bl ack cc-rmmuni ty accept i ndi vi dual respon-

si bi l i t y f or her or hi s behavi or

-

whet her t hat behavi or assul nes t he

f orm of bl ack-on' bl ack horni ci de, gang mernbers vi ol at i ns t he sanct i t y

of the chtrrch, Lrnprotected sexual acdvi ty, gangster rap l yri cs, what-

ever

-

i s f or us t o f unct i on rl erel y as et hni c cheerl eaders sel l i ng woof

ti ckers frorn cal npus or sr.rburbs, rather thar-r sayi ng the di l fi cul t thi ngs

rhar mey be unpopul ar wi t h our f el l ows. Bei ng a l eader does not neces-

sari l y rneen bei r-rg l oved; l ovi ng one' s communi ty l neans dari ng to ri sk

esrrangel rrer-rr and al i enati on fi ' om i r i n che shcl rc rttn i n order to break

t he cycl e of povcrt y and despai r i n whi ch we f i nd oursel ves, over t he

l ong run. For what i s at st ake i s not hi ng l ess t l -ran rhe survi val of our

coLr l l tr y, a nd rl -re Afi i can- Atne ri can p' teopl e thetn sel ves.

Thosc of us on carnpus can al so reach ol l t ro rhose of us l ef t behi nd

on rhe streers. l }e hi stori cal l y bl ack col l eges and uni versi ti es and Afro-

Arneri can Srudi cs .-l eparrments i r-r ti -ri s cour-rtry can i r-rsti tuti onal i ze

sophornore : rnd j uni or ye: rr i nrernshi ps f or communi t y devel oprnenr

rl rrough orga.ni zati ons such as the Chi l drens Defense Ftrnd. Together

we can combat t eenage pregnanci es, bl ack-on-bl ack cri me, and t he

spread of AI DS i rorn drug abuse and Ll l l prot ect ed sexr, ral rel at i ons, and

corrnt er t he spread of despai r and hopel essness i n our court nuui t i es.

Dr. Ki ng di d not di e so t hat hal f of us woul d rnake i t , hal f of us peri sh,

forever rarni shi r-rg two centuri es of agi tati on for our equal ri ghts. We,

t he membcrs of che Tal ent ed Tent h, rnLrst accepr our hi st ori cal respon-

si bi l i t y and l i ve Dr. Ki ngs crecJo t hat none oFus i s f ree unt i l al l of us are

f ree. And rhar al l of us are brot hers and si st ers, as Dr. Ki ng sai d so l ong

ago

-

whi re and bl :rck, Protestant and Cacl rol i c, Ger-rti l e and

Jew

and

Mt rsl i rn, ri ch and poor -

even i f we are not brot hers-i n-l aw.

Ti m O' Br i en

On the Rainy River

Ti m O' Br i en was bor n i n 1946 i n Aust i n, Mi nnesot a, t o an i nsur ance

sal esman and an el ement ar y school t eacher . Bot h of hi s par ent s

wer e vet er ?f l S: hi s f at her had been i n t he Navy i n l wo Ji ma and

Oki nawa dur i ng Wor l d War l l , and hi s mot her had ser ved wi t h t he

WAVES ( Women

Accept ed f or Vol unt eer Emer gency Ser vi ce) . As a

chi l d, O' Br i en spent t i me r eadi ng i n t he count y l r br ar y, l ear ni ng t o

per f or m magi c t r i cks, and pl ayi ng basebal l ( hi s f i r st pi ece of f i ct i on

was cal l ed " Ti mmy of t he Li t t l e League" ) .

O' Br i en at t ended Macal est er Col l ege i n Sai nt Paul , Mi nnesot a,

maj or i ng i n pol i t i cal sci ence. When he gr aduat ed i n 1968, he hoped

t o j oi n t he St at e Depar t ment as a di pl omat - but i nst ead, j ust

weeks

af t er gr aduat i on, he was dr af t ed i nt o t he Ar my. O' Br i en near l y f l ed t o

Canada: dur i ng hi s t r ai ni ng i n For t Lewi s, Washi ngt on, he pl anned

t o deser t , but he went onl y as f ar as Seat t l e bef or e t ur ni ng back.

I n 1969, at t he age of 22, he went t o Quang Ngai , Vi et nam, f i r st

as a r i f l eman and l at er as a r adi o t el ephone oper at or and cl er k. He

compl et ed a 13- mont h t our of dut y, ear ni ng a Pur pl e Hear t and a

Br onze St ar .

Af t er hi s r et ur n t o t he Uni t ed St at es i n 1970, O' Br i en enr ol l ed i n

Har var d' s doct or al pr ogr am i n gover nment and spent hi s summer s

wor ki ng as an i nt er n f or t he Washr ngt on Post . He became a f ul l -

t i me nat i onal af f ai r s r epor t er , cover i ng Senat e heanngs and pol i t i cal

event s. Sever al year s l at er , O' Br i en l ef t bot h hi s gr aduat e wor k and

hi s j ob at t he Posf t o pur sue a car eer as a wr i t er . l n a memoi r , seven

novel s, and many shor t st or i es, O' Br i en has expl or ed t he quest i on

of mor al r esponsi bi l i t y: Who i s r esponsi bl e f or t he 58, 000 Amer i can

sol di er s and mor e t han a mi l l i on Vi et namese peopl e ki l l ed i n bat t l e

bet ween 1965 and 1975?

" On t he Rai ny Ri ver " descr i bes a young man who has t o choose

bet ween goi ng t o Vi et nam and f l eei ng t o Canada t o evade t he dr af t .

He bl ames t he war on ever yone- t he pr esi dent , t he j oi nt chi ef s

of st af f , t he knee- j er k pat r i ot s i n hi s homet own- but ul t i mat el v

17I

1 7 2 Mo DEL TEXTS Fo R wRTTERS

t akes hi s pl ace among t hem, choosi ng t o go t o war . Hi s deci si on

preci pi tates the events of the book, The Thi ngs They Carri ed, j ust as

O' Br i en' s own conf l i ct ed deci si on t o go t o war set t he cour se of hi s

l i f e, f i r st as a sol di er and t hen as a wr i t er .

The Thi ngs They Carri ed (1990) was a fi nal i st for both the Pul i tzer

Pr i ze and t he Nat i onal Book Cr i t i cs Ci r cl e Awar d. O' Br i en' s ot her

si gni fi cant books i ncl ude l f I Di e i n a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and

Ship Me Home (1973), Going after Cacciato (I978), The Nuclear

Age ( I 985) , and l n t he Lake of t he Woods ( 1994) . Ti m O' Br i en l i ves

i n Texas wi t h hi s wi f e and son. He t eaches cr eat i ve wr i t i ng at Texas

St at e Uni ver si t v.

f

his is one story I' ve never rold before. Not to anyone. Not to my

I parents, not to my brother or sister, not even to my wife, To go

inro it, I' ve always thought, would only cause embarrassmenr for all of

us, a sudden need to be elsewhere, which is che natural response to a

confession. Even now I' ll adrnit, the story makes me squirm, For more

than twenty years I' ve had to live wirh ir, feeling rhe shame, rrying ro

puslr ft away, and so by this act of remembrance, by putting the facts

down on paper, I' m hoping to relieve at least some of the pressure on my

dreams. Sdll, it' s :r hard story to tell. All of us, I suppose, like to believe

that in a moral emergency we will behave like the heroes of our youth,

bravely and forthrightly, without thought of personal loss or discredit.

Cercai nl y chac was my convi cci on back i n the surnmer of 1968. Ti m

O' Brien: a secret hero. The Lone Ranger. If the stakes ever became high

enough

-

if the evil were evil enough, if the good were good enough

-

I

would simply Ap a secret reservoir of courage that had been accumulat-

ing inside me over the years. Courage, I seemed to think, comes to us in

6nite quantities, like an inheritance, and by being frugal and stashing it

away and letting it earn interest, we steadily increase our moral capital

in p' ' rsp2l"xtion for that day when the account must be drawn down. It

was a comforting tl-reory. It dispensed with all those bothersome little

accs of daily courage; it offered hope and grace ro the repetitive coward;

it justified the past while amortizing the future.

InJune of 7968,a month afrcr graduating from Macalescer College,I

was drafted to 6ght a war I hated' I was twenty-one years old. Young,yes,

and politically naive, but even so the American war in Vietnam seemed

O' Br i e n * On r h e Ra i n y Ri v e r I 7 3

ro me wrong. Certain blood was being shed for uncerrain reasons. I saw

no uni ry of purpose, no consensus on marrers of phi l osophy or hi story

or law. The very facts were shrouded in uncerrainty: Was ir a civil war?

A war of national liberarior-r or simple aggressioni Who started it, and

when, and whyi What realLy happened ro rhe llSS Maddox onthat dark

night in the Gulf of Tonkini Was Ho Chi Minh a Communisr stooge,

or a nati onal i st savi or, or both, or nei theri What abour the Geneva

Accordsi What about SEATO and rhe Cold Wari Whar about domi-

noesi Ameri ca was di vi ded on these and a thousand orher i ssues, and

the debate had spilled out across the floor of the United Srares Senate

and i nto the streers, and smarr men i n pi nsrri pes coul d not agree on

even the rnosr fundamental rnacters of public policy. The only cerraincy

that summer was moral confusion. It was my view then, and still is,

that you don' t rnake war without knowing why. Knowledge, of course,

is always imperfect, but it seemed ro me thar when a narion goes ro war

ir rnust have reasonable confidence in the jr-rstice and imperative of irs

cause. You can' t fix your misrakes. Once people are dead, you canr make

rhern undead.

In any case rhose were my convicrions, and back in college I had

taken a modesr srand against rhe war. Norhing radical, no horhead

scufl just ringing a few doorbells for Gene McCarrhy, composing a

few tedious, uninspired edirorials for che campus newspaper. Oddly,

though, it was almosr enrirely an inrellectual acrivity. I broughr some

energy ro it, of course, bur ir was rhe energy that accompanies almost

any abstract endeavor; I felt no personal danger, I felt no sense of an

irnpending crisis in my life. Srupidly, wirh a kind of smug removal that I

cant begin to farllom, I assumed rhar rhe problems of killing and dying

did not fall wirhin my special province.

The draft noti ce arri ved onJune 17,1968.Ir was a humi d afrernoon,

I remembea cl oudy and very qui ec, and Id j usr conl e i n from a round

of golf. My mother and farher were having lunch our in the kitchen.

I remember opening up the letter, scanning the firsr few lines, feeling

rhe blood go rhick behind my eyes. I remember a sound in my head. It

wasnt rhi nki ng, j usr a si l enr horvl . A mi l l i on rhi ngs al l ar once

-

I was

rco good for rl-ris war. Too sffrarc, too compassionate, too everything.

It couldn' t happen. I was above it. I had the world dicked

-

Phi Bera

Kappa and summa cum laude and president of rhe srudenr body and a

Full-ride scholarship for grad studies at Harvard. A mistake, maybe

-

a

1, 74 MoDEL TEXTs FoR wRr r ERS

foul-up in the paperwork. I was no soldier. I haced Boy Scouts. I hated

camping out. I hated dirt and tents and mosquiroes. The sight of blood

made me queasy, and I couldn' r tolerare authority, and I didn' t know

a rifle from a slingshot. I was a liber,tl, for Christ sake: If rhey needed

fresh bodies, wl-ry not draft some back-to-rhe-srone-age hawki Or some

dumb j i ngo i n hi s hard har and Bornb Hanoi burron, or one of LBJs

pretty daughrers, or Wesrmoreland' s whole handsome family

-

neph-

ews and nieces and baby grandson. There should be a law I thought. If

you support awar, if you think ir' s worth rhe price, rhat' s fine, bur you

have to

Put

your own precious fluids on rhe line. You have to head for

the front and hook up with an infantry unir ar-rd help spill the blood.

A' d you have ro bring along your wife, or

),our

kids, or your lover. A

l aw, I t houghr .

s I remember rhe rage i n my sromach. Later i r burned down to a

snroldering self-pity, rhen to numbness. Ar dinner rhat nighr my father

asked what my plans were.

"Norhing,"

I said.

"

Wait."

I spcnr rhe surnmer of i 968 u' orki ng i n an Armour rnear-packi ng pl ant

ir-r rny homero' uvn of Worrhington, Minnesora. The planr specialized

in pork products, and for eighr hours a day I srood on a quarrer-mile

assembly line

-

more properly, a disassembly line

-

removing blood

clots frorn the necks of dead pigs. Myjob rirle, I believe, was Declotter.

After slaughrer, rhe hogs were de.:apitated, splir down the length of the

belly, pried open, eviscerated, and srrlrng up by rhe hind hocks on a high

conveyer belr. Then gravity rook over. By che rime a carcass reached my

spot on the line, che fuids had rnostly drained ouc, everyrhing excepr

for thick clots of blood in rhe neck and upper chest cavity. Tor.,nou.

the stuf{, I used a kind of water gun. The machine was heavy, maybe

eighry pounds, and was suspended from the ceiling by a heavy rubber

cord. There was some bounce ro i t, an el asri c up-and-down gi ve, and

the rrick was ro maneuver rhe gun with your whole body, noc lifting

with the anns, jusr lerrir-rg rhe rubber cord. do the work for you. At

one cnd was a tigger; ar rhe muzzle end was a small nozzle and a steel

roller brush. As a carcass passed by, youd lean forward and swing the

gun up againsr rhe clors and squeeze the tigger, all in one morion, and

rhe brush would whirl and water would come shooring our and youd

hear a quick splarering sound as rhetlots dissolved into a fine red misr.

It was nor pleasanr work. Goggles were a necessicy, and a rubber apron,

but even so it was like srandi.g for eighr hours ^ i^yunder a l,rk"warm

blood-shower. At nighr Id go home sleiling of pig.It wouldn' r go away.

Even after a hot barh, scrubbins hard, rh" srink *i,

"l-"y,

,h..I

_

like

ol d bacon, or sausage, a dense greas/

pi g-sri nk thar soaked deep i nto

rny ski ' and hai r. Arno.g ocher rhi ngs, I rernernbec i r was tough g.rri rrg

dates rhar summer. I felr isolared; I spent a lor of cime alone. A"; rhere

was also char drafr norice tucked away in my wallet.

In rhe evenings Id somerimes borrow my farher' s car and d,rive

aimlessly around rown, feeling sorry fo, *y.eli rhinking about the war

and the pig factory and how rny life seemed ro be collapring toward

slaughter. I felr paralyzed. All around me the oprions seemed ro be

narrowing, as if I were hurrling down a huse black funnel, rhe whole

world_ squeezing in righr. Tlrere was no h"ppy way our. The govern-

ment had ended mosr graduare school defermenrs; the wairing iirt, fo,

rhe National Guard and Reserves were impossibly long; my health was

solid; I didn' t qualify for co srarus

-

no religious grounds, no hisrory

as a pacifrst. Moreover, I could nor claim ro be c-rpposed, ro war as a

matcer of general principle.

-fhere

were occasions, i believed

, when a

nation was jusrified in using nrilitary force to achieve irs end,s, ro srop a

Hitler or some comparable evil, and I told myself thar in such circum-

stances I would' ve willingly marched off to rhe battle. The problem,

though, was thar a draft board did not let you choose your war.

Beyond all this, or ar rhe very cenrer, was the raw fact of terror. I

di d nor wanr ro di e. Not evcr. But certai nl y nor rhen, not there, nor

in a wrong war. Driving r-rp Main srreer, pasr rhe courrhouse and che

Ben Franklin srore, I somecirnes felr rh" i"a. spreading inside me like

weeds. I irnagined myself dead. I imagined myself doing things I could

not do

-

charging an enemy position, caking aim at another human

being.

Ar some point in mid-July I beuan thinking seriously about Canada. 1o

f}e border lay a few hundred miles norrh, an eight-hour drive. Boch

my conscience and my insri' crs were telling ffre

-ro

make a break for

it, just rake off and run like hell and never srop. In the beginning rhe

idea seemed purely absrract, the word canada printing ir."f o,rr ii -y

head; bur after a rime I could see parricula. shap"s orrdl-"g"s, rhe ror.y

details of rny own future

-

a horel room in ivinnip eg, a-battered old

suitcase, rny fbrher' s eyes as I rried ro explain myself ou., ,h. relephone.

O' B r i c n o On r h e Ra i n y Ri v e r I 7 5

. , - l

f 76 MoDEL TEXTS FoR wRr r ERS

I could almost hear his voice, and my morhers. Run, Id think. Then Id

think, Impossible. Then a second later Id think, Run.

It was a kind of schizophrenia. A moral split. I couldn' t make up

my mind. Ifeared the war, yes, but I also feared exile. I was afraid of

walking away from my own Iife, my friends and my family, my whole

history, everything chat matcered to me. I feared losing the respecr of

my parents. I feared the law. I feared ridicule and censure. My home-

town was a conservative little spot on the prairie , aplace where tradition

counted, and it was easy to imagine people sitting around a rable down

at the old Gobbler Caft on Main Streer, coffee cups poised, the conver-

sation slowly zerorng in on the young O' Brien kid, how rhe damned

sissy had taken off for Canada. At night, when I couldn' t sleep, Id

sometime s carry on 6erce arguments with those people. I d be scream-

ing at them, telling them how much I detested their blind, thoughtless,

automatic acquiescence to it aIl, their simple minded patriotism, their

prideful ignorance, their love-it-or-Ieave-it pladrudes, how they were

sending me offto 6ght awar they didn' t undersrand and didn' t wanr ro

understand.I held them responsible. By God, yes, I did. AIlof rhem

-

I

held them personally and individually responsible

-

the polyestered

Kiwanis boys, the merchants and farmers, the pious churchgoers, the

chatty housewives, the PTA and the Lions club and the Veterans of

Foreign Wars and the 6ne upstanding gentry our ar rhe country club.

Th.y didnt know Bao Dai from the man in the moon. Th"y didn' t

know history. Th"y didn' t know the 6rst thing about Diem' s tyranny,

or the nature of Vietnamese nationalism, or the long colonialisrn of the

French

-

this was all too damned compli car.ed, it required some read-

irg

-

but no matter, it was a war to stop the Communisrs, plain and

simple, which was how rhey liked things, and you were a rreasonous

pussy if you had second thoughts abour killing or dying for plain and

simple reasons.

I was bitter, sure. But it was so much more than thar. The emotions

went from outrage to terror to bewilderment to guilt to sorrow and

then back again to outrage. I felt a sickness inside me. Real disease.

Most of rhis I' ve rold before, or ar least hint ed ar, bur what I have

never told is the full rrurh. How I cracked. How at work one morn-

ing, standing on the pig line, I felr somerhing break open in my chest.

I don' t know what it was. I' ll neVer know. Bur it was real, I know rhar

much, it was a physical ruprure

-

a cracking-leaking-popping feeling. I

C) ' l J r i e n * On t h e l l . a i n y Ri v e r 1 7 7

remember dropping my wacer gun.

Quickly,

ahnosr wirhout rhougl-rt, I

took offmy apron and walked our of rhe planr and drove home. Ir *",

midrnorr-ri' g I remember, and the house was empry. Down in my chest

there was sri l l rhat l eaki ng sensari on, somerh i ngvery warl n and preci ous

spilling out, and I was .ou.r"d wirh blood ;rnd hog-stink,

",ld

for a

long while I just concentrated on holding myself rogetl-rer. I rernernber

taking a hor shower. I remernber packing a suitcase and carrying ir our

to the kitchen, standing very srill for a few rninures, looking carefully

at the familiar objects all around rne. The old chrome roasrer, rhe tele-

phone, the pink and whire Forrnica on rhe kitchen counrers. The room

was full of brighr sunshine. Everything sparkled. My hor_rse, I thoughr.

My life. I' m nor sure how long I srood rhere, bur later I scribbled our a

short note to my parenrs.

whar ir said, exactIy,I don' r recall now. Somerhing vaglre. Taking oll

will call, love Tirn.

I drove north.

15

It' s a blur now as ir was then, and all I rer' ernber is a sense of high

velocity and rhe feel of rhe steering wheel in n-ry hands. I was ri.ling

on adrenaline. A giddy feeling, in a way, excepr rhere was rhc drcamy

edge of i mpossi bi l i ry ro i r-l i ke runni r-rg a dead-enc-l rnaze-no way

out

-

i r coul dn' r come to a happy concl usi on and yet I was doi ng i t

anyway because it was all I could rhink of ro do. Ir was pure llighr,

fast and mi ndl ess. I had no pl an.

Jusr

hi r rhe border at hi gh .p""d

and crash rhrough and keep on running. Near dusk I passed rhrough

Bemidji, then rurned northeast toward L-rternarional Falls. I .p..rr rt"

ni ght i n the car behi nd a cl osed-down ges stari on a hal f mi l e from rfi e

border. In rhe morni ng, afrer gassi ng' p, I headed srrai ghr west al ong

the Rainy River, which separares Minnesora frorn Canada, and which

for me separated or-re life from another. The l:rnd was mosrly wilderness.

Here and there I passed a morel or bai t shop, but otherwi se rhe counrry

unfolded in great sweeps of pine and birch and sumac.

' lhough

ir -a.,

still August, the air already had the smell of Ocrober, foorb"il season,

piles of yellow-red leaves, everyrhing crisp and clean. I rernernber a huge

blue sky. off ro rny righr was the Rainy River, wide as a lake in places,

and beyond rhe Rainy fuver was Canada.

For a while I just drove, noc airning ar anything, rhen in rhe lare

morning I begar-r looking for a place to lie low for a day or rwo. I was

-d

O' B r i e n m On r h e Ra i n y Ri v e r 7 7 9

I 7 B Mo DEL TEXTS Fo R wRI TERS

exhausted, and scared si ck, and around noon I pul l ed i nro an ol d fi sh-

ing resort called the Tip Top Lodge. Actually it was nor a lodge ar all,

just eight or nine tir-ry yellow cabins ch-rsrered on a peninsula thar-jutted

northward into the Rainy River. The place was in sorry shape. There

was a dangerous wooden dock, an old minnow rank, a flimsy tar paper

boarhouse along the shore. The main building, wl-rich srood in a clus-

ter of pir-res on high ground, seemed ro lean l' teavily ro one side, like a

cripple, rhe roof sagging roward Canada. Briefly, I rhoughr abour rurn-

i ng around, j usr gi vi ng up, buc rhen I gor our oi rhe car and wal ked up

to the fronr porch.

The man who opened the door rhar day is che hero of my life. How

do I say rhis withour sounding sappyi Blurr ir our

-

rhe man saved,

me. He ollered exactly what I needed, wirhour questions, withour any

words at all. He took me in. He was there ar rhe crirical cime

-

a silent,

watchful

Presence.

Six days larer, when ir ended, I was r-rnable ro find a

proper way ro rhank hirn, and I never have, and so, if norhing else, tfiis

story represents a small gesrure of gracicude twenty years overdue.

Even after two decades I can close my eyes and return ro that porch

at che Tip Top Lodge. I can see che old guy sraring ar me. Elroy Berdahl:

eighry-one years old, skinny and shrunken and rnosrly bald. He wore a

Il annel shi rt and brown work pants.In one hand,I remernber, he carri ed,

a green apple, a small paring knife in the other. His eyes had the bluish

gray col or of a razor bl ade, the sarne pol i shed shi ne, and as he peered up

at me I felt a strange sharpness, almost painful, a curting sensarion, as

i f hi s gaze were somehow sl i ci ng me open. In parr, no doubr, i r was my

own sense of gui l t, but even so I' m absol utel y certai n rhar rhe ol d man

took one look and went right to the hearr of rhings

-

a kid in rrouble.

When I asked for a room, Elroy made a little clicking sound wich his

rongue. He nodded, l ed me our ro one of the cabi ns, and dropped a

key in my hand. I rernember smiling ar him. I also remember wishing I

hadn' t. The old man shook his head as if to tell rne ir wasn' r worrh rhe

bother.

20

"Di nner

ar fi ve-thi rryi ' he sai d."you ear fi shi "

' Anything,"

I said.

Elroy grur-rred and said,

"Illbet!'

we spenr six days rogerher ar rlre Tip Top Lodge.

Jusr

rhe rwo of us.

Tourist season was over, and there were no boars on the river, and the

wilderness seemed to withdraw into a great permanent stillness. Over

those six days Elroy Berdahl and I took most of our meals togecher. In

the rnornings we sornetimes went out on long hikes into the woods, and

at night we played Scrabble or listened to records or sat reading in front

of his big scone fireplace. At times I felt the awkwardness of an incruder,

buc Elroy accepted me into his quiet routine without fuss or ceremony.

He took my presence for granted, the same way he might' ve sheltered

a stray ca(.

-

no wasted sighs or pity

-

and there was never any talk

about i t.Jusr the opposi te. Whar I remember morc than anythi ng i s the

man' s willful, almosr ferocious silence.In all that time together, all those

hours, he never asked the obvious questions: Why was I therei Why

al onei Why so preoccupi edi If El roy was curi ous about any of thi s, he

was careful never to put it into words.

My hunch, though, is that he already knew. At least the basics. After

al l , i t was 1968, and guys were burni ng draft cards, and Canada was j ust

a boar ride away. Elroy Berdahl was no hick. His bedroom, I remember,

was cluttered with books and newspapers. He killed me at the Scrabble

board, barely concentrating, and on those occasions when speech was

necessary he had a way of compressing Iarge thoughts into small , cryp-

tic packets of language. One evening, just at sunset, he pointed up at an

owl circling over rhe violer-lighted forest to the west.

"H"y,

O' Bri en," he sai d."There' sJesus." 25

The man was sharp

-

he didn' t miss much. Those razor eyes. Now

and then hecl catch me staring out at the river, at the far shore, and I

could almosr hear rhe tumblers clicking in his head. Maybe I' m wrong,

but I doubt it.

One thing for certain, he knew I was in desperate trouble. And he

knew I couldn' t talk about it. The wrong word even the right

word

-

and I would' ve disappeared. I was wired and jittery. My skin

felt too tight. After supper one evening I vomited and went back to my

cabin and lay down for a few moments and then vomited again; another

time, in the middle of the afternoon,I began sweating and couldn' r shut

it ofl. I went through whole days feeling dizzy with sorrow. I couldn' t

sleep; I couldn' r lie srill. At night I d ross around in bed, half awake,

half dreaming, imagining how Id sneak down ro the beach and quietly

push one of the old man' s boats our into the river and starr paddling my

way toward Canada. There were times when I thoughr Id gone offthe

psychic edge. I couldn' t tellup from down, I was just falling and late in

t 8 0 Mo DE L T E X T S F o R wRr r E RS

the night Id, lie there watching weird pictr-rres spin rhrough nry l-read.

Getti ng chased by the Border Patrol - hcl i copters and searchl i ghcs

and barki ng dogs

-

IA be crashi ng through rhe woods, I d be down on

rny hands and knees

-

peopl e shouti ns our my name

-

rhe l aw cl os-

i ng i n on al l si des

-

my hornetown draft board and the FBI and the

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. it all seemed t^zy and irnpossible.

Twenty-one years ol d, an ordi nary ki d wi th al l the ordi nary dreams and

ambitions, an.1 all I wanted was to live the life I was borr-r ro

-

a main-

stream l fe- I l oved basebal l and harnburgcrs and cherry Cokes

-

and

now I was offon the margi ns of exi l e,l eavi ng my counrry forever,and i t

seemed so impossible and terrible and sad.

Iin not sure how I rnade it rhrough those six days. Mosr of ir I can' c

remember, On two or three afternoons, to pass some ti me, I hel ped

Elroy get the place ready for winter, sweeping down the cabins and

hauling in rhe boats, lirrle chores rhar kepr my body moving. The days

were cool and bright. The nights were very dark, One morning rhe old

man showed rne how to splic and stack firewoocl, and for several hours

we j ust worked i n si l ence or,rr behi nd hi s house. Ar one poi nc, I remcrn-

ber, Elroy put down his maul and looked at rne for a long rime, his lips

drawn as if framing a difficult question, br-rt rhen he shook his head

and wenc back to work. Thc rnans sel{-control was antazing. He never

pri ed. He never put me i n a posi ti on that requi red l i es or deni al s. To

an extent, I suppose, hi s reri cence was rypi cal of thar part of Mi nne-

soca, where privacy sdll held value, and even if I cl bee n walking around

with some horrible defbrmity

-

four arms and three heac{s

-

l' 11 s111s

the ol d man woul d' ve tal ked about everythi ng except those exrra arms

and heads. Simple politeness was parr c-rf it. Bur even rrrore rhan that, I

thi nk, the man understood that words wefe i nsuffi ci ent. The probl em

had gone beyond discussion. Dtrring that long sun-uner I d been over

and over the vari ous argumenrs, al l rhe pros and cons, and i r was no

longer a question that could be decided by an act of pure reason. Intel-

l ect had come up agai nst emoti on. My consci ence tol d rne ro run, bur

some irrational and powerful force was resistine like a weighr pr-rshing

me toward the war. What it came down to, srupidly, was a sense of

sharne. Hot, scupicl sharne. I did nor wanr people ro rhink badly of me.

Not rny parents, not my brother and sister, not even rhe folks .lown ar

the Gobbler Cafe.I was ashamed to be rhere at ttre Tip Top Lodge. I

was asharned of my conscience, as[amed ro be doing the righr thing.

O' B r i e n o On t h e Ra i n y Ri v e r 1 8 1

Sorne of this Elroy must' ve understood. Not the details, of course,

but the plain fact of crisis.

Although the old man never confronted me abouc it, there was one

occasion when he came close to forcing the whole thing out into the

open. It was early evening, and wedjust finished supper, and over coffee

and dessert I asked hirn abouc rny bill, how much I owed so far. For a

long while the old man squinted down at the tablecloth.

"We11,

che basic rate' ,' he said,

"is

fifty bucks a night. Not counting

rneals. This rnakes four nighrs, righti"

I nodded. I had three hundred and twelve dollars in my wallet.

Elroy kept his eyes on the tablecloth."Now that' s an on-season price.

To be fair,I suppose we should knock it down apegor twol' He leaned

back in his chair."What' s a reasonable number, you figurei"

"I

dont knowj ' I sai d."Forty?"

"Forty' s

good. Forry a night. Tl-ren we tack on food

-

say another

hundredi Two hundred sixry cotali"

"I

guessl '

He raised his eyebrows."Too muchi"

"No,

thar' s fair. Its fine. Tomorrow, rhough . . . I rhink Id betrer take

offtomorrow."

Elroy shrugged and began clearing rhe table. For a time he fussed

with the dishes, whistiing to himself as if the subject had been settled.

After a second he slapped his hands together.

"You

know what we forgoti" he said.

"We

forgot wages. Those odd

jobs you done. What we have to do, we have to figure out what your

time' s worth. Your last job

-

how much did you pull in an houri"

"No[

enough," I said.

' A

bad one?"

"Yes.

Pretty badi'

Slowly then, without intending any long sermon, I told him about

my days at the pig plant. It began as a straight recitation of the facts,

but before I could stop myself I was talking about the blood clots and

the water gun and how the smell had soaked into my skin and how I

couldn' t wash it away.I went on for a long rime. I told hirn about wild

hogs squealing in my dreams, the sounds of butchery, slaughterhouse

sounds, and how Id sometimes wake up with that greasy pig-scink in

my throat.

When I was finished, Elroy nodded at me.

35

40

I 8 2 Mo DEL TEXTS Fo R wRI TERS

"we11,

ro be honesri' he said,

"when

you firsC showed up here, I

wondered about all chat. fhe aroma, I mean. Smelled like you was

awful {amned fond of pork chopsi' The old man almost smiled. He

mad"e a snuflling sound, then sar down wirh a pencil and a piece of

paper."So whard rhi s crud j ob pay? Ten bucks an hour? Fi freeni "

"Lessi '

Elroy sl-rook his head.

"Let' s

make it fifteen. You pur in twenty--{ive

hours 6ere, easy. Thar' s three hundred seventy-five bucks total wdges.

we subrracr rhe two hundred sixty for food and lodging,I still owe you

a hundred and 6fteen'

He took four fifties out of his

table.

"Cal l

i t eveni ' he sai d'

"Noi '

"Pick

it up. Get

Yours

eLf ahaircur' '

The mon-ey lay on the table for the rest of the evening. It was still

rhere when I went back to my cabin. In the morning, thorrgh, I found an

envelope tacked ro my door. Inside were the four fifties and a two-word

nore rhar said EIr,4ERGENCY FUND'

I

l ne l - l t an Knew.

Looking back afrer rwenry years,I

sornetimes wonder if the events of

th"t ,,rl-er didn' t happen in some other dimension, a place where

your life exists before you ve lived ir, ancl where it goes afterward. Nonc

of ir ever seerned real. During nly titne at the Tip Top l.odge I had the

feeling that I d slipped out of my own skin, hovering a few feer away

while sorne poor yo-yo with nry name and face tried to make his way

toward a furure he didnt understand

and didn' t want. Even now I can

see myself as I was then. It' s like watching an old home movie: I' m young

and tan and fir. I' ve got hair

-lots of it. I don' t smoke or drink. I' m

wearing faded blue jeans and a white polo shirt. I can see rnyself sitting

on Elroy Berdahls dock near dusk one evening, the sky a bright shim-

mering pink, and I' m finishing up a letrer lo. my

Parents

chat tells what

I' -

"bo,rt

to do and why I' m doing it and how sorry I am thar I d never

found the courage to talk to thern about it. I ask them not to be angry'

I rry to explain some of my feelings, but there aren' t enough words, and

so I just r"y th"r its a thing thar has to be done. At the end of the letter

I talk abour the vacations we used to take up in this north country, at a

O' B r i e n

. On t h e Ra i n y Ri v e r 1 8 3

place called Whitefish Lake, and how the scenery here reminds me of

ihor. good times. I tell them I' m fine. I tell them I' 11 write agairt frorn

Winnipeq or Montreal or wherever I end up.

On my lasr full day, rhe sixth d:ry, che old man took tne out fishing

on tlre Rainy River. The afiernoon was sunny and cold. A stiff^ \reeze

came ir-r from the north, and I remember how the little fourteen-foot

boat made sharp rocking motions as we pushed ofl from the dock. The

current was fast. All around us, I remember, there was a vastness to the

world, an unpeopled rawness, just the trees and the sky and the warer

reaching out toward nowhere. The air had the brirle scent of October'

For ten or fifteen minuces Elroy held a course uPstrealn, the river

cl-rop,py and silver-gray, tl-ren he turned straight north and put the engine

on fr-rll rhrotrle. I felt the borv lift benearh me. I remember the wind in

my ears, the sound of the old outboard Evinrude. For a time I didn' t pay

arrention to anything, just feeling the cold sPray against my face, but

then it occttrred to ffIe that at solne point we must ve passed into Cana-

dian waters, across that dotted line between two differenc worlds, and I

remember a sudden cightness in rny chest as I looked up and warched

the f' ar shore come at me. Tl-ris wasnt a daydrearn. It was tangible and

real. As we came in toward land, Elroy cut the engitre, letting the boat

fishtail lightly about twenty yards off shore. The old man didn' t iook at

me or speak. Bendi ng down, he opened up hi s tackl e box and busi ed

hirnself with a bobber and a piece of wire leader, hurnming to himselfl,

hi s eyes down.

It struck l ne then that he l nustve pl anned i t. I' l l never be certai n,

of course, but I think he tneant to bring me uP against the realities, to

guide rne across the river and to take me to the edge and to stand a kind

of vigil as I chose a life for myself.

I remember staring ar the old man, rhen at my hands, then at

Canada. The shoreline was dense with brush and tirnber. I could see

ti ny red berri es on the bushes. I coul d see a squi rrel up i n one of the

birch trees, a big crow looking at me frorn a boulder along the river'

Thar close

-

rwenry yards

-

and I could see the delicate latticework

of the leaves, the texture of rhe soil, the browned needles beneath the

pines, the configurations of geology and human history. Twenty yards'

I could' ve done it. I could' ve jurnped and started switnming for my life'

Inside me, in my chest, i felt a terrible squeezing

Pressure.

Even now, as

shi rt pocket and l ai d them on the

6 5

1 8 4 MODE L T E X T S F OR WRI T E RS

I write this, I can scill feel that tightness. And I want you to feel ic

-

the

wind coming off the river, the waves, the silence, the wooded frontier.

You' re at the bow of a boat on the Rainy fuver. You' re twenty-one years

old, you' re scared, and there' s a hard squeezing

Pressure

in your chest.

What woul d you do?

Would you jumpi Would you feel pity for yourselfi Would you

rhink about your farnily and your childhood and your dreams and all

you re leavir-rg behindi Would it hurt? Would it feel like dyingi Would

you cry, as I did?

I tri ed to swal l ow i t back. I tri ed to smi l e, excePt I was cryi ng.

Now perl-raps, you can understand why I' ve never told this story

before. It' s not just the embarrassffIent of tears. That' s part of it, no

doubt, but what embarrasses lne rnuch rrore, and always will, is the

paralysis that took rny l-reart. A moral freeze: I couldn' t decide, I couldn' t

act,I coul dn' t corxport rnysel f wi th even a

Pretense

of modest human

dignity.

A11 I could do was cry.

Quietly,

not bawling, just the chest-chokes.

At the rear of tl-re boar Elroy Berdahl pretended not to notice. He

hel d a fi shi ng rod i n hi s hands, hi s head bowed to hi de hi s eyes. He

kept l-rumming a soft, monotonous little tune. Everywhere, it seemed,

in the trees and water and sky, a great worldwide sadness came pressing

down on me, a crushing sorrow, sorrow like I had never known it before.

And what was so sad, I reahzed, was that Canada had become a pidful

fantasy. Silly and hopeless. It was no longer a possibiliry. Right then,

wi th the shore so cl ose, I understood that I woul d not do what I shoul d

do.I would not swim away frorn rny hometown and my country and my

life. I would not be brave. That old image of rnyself as a hero, as a man

of conscience and courage, all that was just a threadbare pipe dream'

Bobbing there on the Rainy River, looking back at the Minnesota shore,

I felt a sudden swell of helplessness come ovcr mc, a drowning sensation,

as if I had toppled overboard and was being swePt away by the silver

waves. Chunks of my own history {lashed by. I saw a seven-year-old boy

in a white cowboy hat and a Lone Ranger mask and a pair of holstered

six-shooters; I saw a twelve' year' old Little League shortstop pivoting

to turn a double play; I saw a six[een-year-old kid decked out for his

first prom, looking.pifry in a white tux and a black bow tie, his hair cut

shorr and flat, his shoes freshly polished. My whole life seemed to spill

out into the river, swirling away fr0in me, everything I had ever been

O' B r i e n

* On t h e l { a i n Y Ri v e r 1 8 5

or ever wanted to be. I couldn' t ger my breath; I couldnt stay afloat; I

coul dnt tel l whi ch way to swi m. A hal l uci nati on, I suppose, but i t was

as real as anyrhing i would ever feel. I saw my

Parents

calling to 1xe

from rhe faruhorii.,". I saw rny brother and sister, all the townsfolk'

the rnayor and the entire Chamber of Commerce ancl all n-ry old teach-

.r,

".,i

girlfriends and high school buddies. Like some weird sPorting

evenr: .ri.rybody ,.r"arrrir-rg frotn the sidelines, rooting me on

-

a loud

stadium roar. Hotdogs and

PoPcorn

-

stadium smells, stadiurn heat'

A squad of cheerle"d"r, did carrwheels along the banks of the Rainy

R.iver; they had megaphones and pompoms and smooth brown thighs.

The crowd swayedl"i,

"trd

righr. A marching band played fight songs.

All my aunrs and uncles were there, and Abraharn Lincoln, and Saint

George, and a ni ne,year-ol d gi rl named Li nda who had cl i ed of a brai n

,tl-o-l. back in fifth grade, and several members

pf the United States

Senate, and a blind plet scribbling nores, and LBJ, and Huck Finn, and

Abbie Hoffman, ar",J

"il

rhe dead soldiers back from the grave, and the

many rhousands who were later to die

-

villagers with terrible burns'

little kids withour arms or legs

-

Yes,

and tl-reJoint Chiefs of Staffwere

there, ancl a couple of popes, and a 6rst lieutenant nanled

Jimrny

Cross,

and rhe last survivi,' ,g u.t"r"n of the Ame rican Civil War, andJane Fonda

dressed up as Barbarella, and an old man sprawled beside a pigpen, and

rny grandfather, and Gary Cooper, and a kind-faced woman cxrying

".,

.r*br"lla and a copy of Plato' s Republic, and a rnillion ferocious citi-

zens waving flags of

"ll

shapes and colors

-

people in hard hats, people

in headbands

-

they were all wl-rooping and chanting end urging me

toward one shore or the otl-rer. I saw faces from rny c-listant past and

distanr future. My wife was rhere. My unborn daughter waved af me,

and my rwo sons hopped up and down, and a drill sergeant named

Blyton sneered and shot up a frnger and shook his l-read. There was a

choir in brighr purple robes. There was a cabbie from the Bronx. There

was a slim young man I would one day kill with a hand grenade along a

red clay trail outside the village of My Khe'

The litrle aluminum boat rocked softly beneath me. There was the

wind and the sky.

I tried to will mYself overboard.

I gripped rhe edge of rhe boat and leaned forward and thought,

Now.

I did try. It just wasn' t

Possible.

t* r*r '

186 MoDEL TEXTS FoR wRr r ERS

70 A11 those eyes on me

-

the rown, the whole universe

-

and I

coul dn' c ri sk che embarrassment. ft was as i f there were an audi ence ro

my Iife, that swirl of faces along rhe river, and in my head I could hear

peopl e screarri ng at me. Trai tor! they yel l ed. Turncoar! Pussy! I fel t

myself blush. I couldn' t rolerare it. I couldn' r endure the mockery, or

the disgrace, or the parrioric ridicule. Even in my imagination, the shore

just twenry yards away,I couldn' r make myself be brave. Ir had norhing

to do with n-rorality. Embarrassmenr, thar' s all ir was.

And ri ght chen I submi tred.

I would go ro the war

-

I would kill and maybe die

-

because I w:rs

embarrassed not ro.

That was the sad thi ng. And so I sar i n rhe bow of rhe boat and

cri ed.

It was loud now. Loud, hard crying.

Elroy Berdahl remai' ed quier. He kepr fishing. He worked his line

with rhe tips of his fingers , pariently, squinring our ar his red and whice

bobber on rhe Rainy River. His eyes were flat and irnpassive. He didn' t

speak. He was sirnply rhere, like rhe river and the late-sLrmlner sun.

And yet by his presence, his mure warchfulness, he made ir real. He

was the true audi ence. He was a wi rness,l i ke God, or l i ke the gods, who

look on in absolute silence as we live our lives, as we make our choices

or fail to rnake thern.

' Ain' c

bitingi' he said.

Then afrcr a time the old rnan pr-rlled in his line and turned rhe boat

back toward Minnesota.

I don' t remember saying goodbye. Thar lasr nighr we had .linner

together, and I went to bed early, and in rhe morning Elroy fixed break-

fasc for rne. When I rold him Id be leaving, rhe old rnan nodded as if he

already knew. He looked down at the table and smiled.

At some poi nt l ater i n the morni ng i r' s possi bl e thar we shook

hands- I j ust don' t r emember - bur I do know r hat by r he t i me I d

finished packing the oid man had disappeared. Around noon, whe' I

took my suircase our ro rhe car, I noticed rhar his old black pickup truck

was no longer parked in front of the house. I went inside and waired for

a while, bur I fek a bone cerr.ainry thar he wouldn' r be back. In a way, I

thought, it was appropriate. I washed up rhe breakfasr dishes, lefr his

O' Br i e n

* On r h e R: r i r . r y Ri v e r l B7

two hundred dollars on the kitchen counter, got into the car, and drove

south toward home.

The day was cloudy. I passed through towns with familiar names,

tlrrough the pine forests and down to the

Pralrre,

and rhen to Vietnam'

wlrere I was a soldier, and then home again,I survived, but it' s not a

hrppy ending. I was a coward. I went to the war'

80

7 5

You might also like

- The Ethical SlutDocument185 pagesThe Ethical SlutAna Maria Matei92% (13)

- What Smart Students Know - Adam RobinsonDocument286 pagesWhat Smart Students Know - Adam RobinsonTieu Dat100% (4)

- Hugh Seton Watson Nations and States Methuen Co. Ltd. 1977 PDFDocument566 pagesHugh Seton Watson Nations and States Methuen Co. Ltd. 1977 PDFAnonymous uhuYDKY100% (4)

- Leon Uris - Mila 18Document22 pagesLeon Uris - Mila 18Debapratim GhoshNo ratings yet

- The Wind's Twelve Quarters - Ursula K. Le GuinDocument105 pagesThe Wind's Twelve Quarters - Ursula K. Le GuinVíctor Villacorta80% (10)

- Audre Lorde, The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master's House PDFDocument4 pagesAudre Lorde, The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master's House PDFMila Apellido100% (1)

- Beijing Mingrui Lighting Technology Co., LTD.: CatalogDocument29 pagesBeijing Mingrui Lighting Technology Co., LTD.: CatalogvanthangNo ratings yet

- RAVENING WOLVES BY Monica Farrell PDFDocument65 pagesRAVENING WOLVES BY Monica Farrell PDFVesnaMilic100% (1)

- This Bridge Called My BackDocument104 pagesThis Bridge Called My BackIvona Ivkovic100% (33)

- Enver Hoxha. Laying The Foundations of The New AlbaniaDocument614 pagesEnver Hoxha. Laying The Foundations of The New AlbaniaAnatolijus Stalėns50% (2)

- Common Sense Renewed PDFDocument134 pagesCommon Sense Renewed PDFPatrick John Villanueva100% (1)

- Personal Narrative Writing AssignmentDocument4 pagesPersonal Narrative Writing Assignmentapi-252721756No ratings yet

- Personal Narrative Writing AssignmentDocument4 pagesPersonal Narrative Writing Assignmentapi-252721756No ratings yet

- OntherainyrivertextDocument9 pagesOntherainyrivertextapi-291608086No ratings yet

- Jolly 10Document5 pagesJolly 10satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Sands of TimeDocument211 pagesSands of TimebetutzNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of The 1988 Soviet Union Peace WalkDocument7 pagesSynopsis of The 1988 Soviet Union Peace WalkOur MoveNo ratings yet

- 2406 Dallas Morning News 1938-01-30 1-10Document1 page2406 Dallas Morning News 1938-01-30 1-10Richard TonsingNo ratings yet

- Being Muslim in AmericaDocument36 pagesBeing Muslim in AmericaSalman M. FaiziNo ratings yet

- A Stranger in The MirrorDocument173 pagesA Stranger in The MirrorbetutzNo ratings yet

- Al Qaeda Member's Home. The Manual Was Found in A Computer FileDocument28 pagesAl Qaeda Member's Home. The Manual Was Found in A Computer FileBATTILALNo ratings yet

- Cicero - Six Orations - Selection Attempt #2Document21 pagesCicero - Six Orations - Selection Attempt #2peteatkinson@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- Full Text of A Mission To Gelele, King of DahomeDocument362 pagesFull Text of A Mission To Gelele, King of DahomejnukpezahNo ratings yet

- May 2011 Black and Pink NewsletterDocument10 pagesMay 2011 Black and Pink NewsletterJason LydonNo ratings yet

- Lucifer v02 n10 June 1888Document160 pagesLucifer v02 n10 June 1888lisNo ratings yet

- Dream SpeechDocument6 pagesDream Speechjosephbarrios634No ratings yet

- Cicero'S Attitude To The TriumvirateDocument118 pagesCicero'S Attitude To The TriumvirateNina ŠćepanovićNo ratings yet

- Autobiography of Andrew CarnegieDocument0 pagesAutobiography of Andrew CarnegieBrandon BakerNo ratings yet

- 1 Jamuary Newsletter 2013 PDFDocument9 pages1 Jamuary Newsletter 2013 PDFapi-238984130No ratings yet

- Canada and The Korean War - Fifty Years OnDocument26 pagesCanada and The Korean War - Fifty Years OnAbbie LiNo ratings yet

- THE BRASS CHECK: A Study of American Journalism: The Biggest Exposé on Sensational Media Coverage and Unethical Journalism in USA (From the Renowned Author, Journalist and Pulitzer Prize Winner)From EverandTHE BRASS CHECK: A Study of American Journalism: The Biggest Exposé on Sensational Media Coverage and Unethical Journalism in USA (From the Renowned Author, Journalist and Pulitzer Prize Winner)No ratings yet

- Letter To My Son - CoatesDocument16 pagesLetter To My Son - CoatesEmil ONeillNo ratings yet

- ChairmanMao ImportantTalksWithGuestsFromAsia Africa LatinAmerica 1966Document16 pagesChairmanMao ImportantTalksWithGuestsFromAsia Africa LatinAmerica 1966Agustín BautistaNo ratings yet

- What I Saw in America by G K ChestertonDocument241 pagesWhat I Saw in America by G K Chestertonlek faizNo ratings yet

- May 6, 1856Document4 pagesMay 6, 1856TheNationMagazine100% (1)

- The Politics of Western Marxism ReflectiDocument7 pagesThe Politics of Western Marxism ReflectiCarlos AfonsoNo ratings yet

- Waco HorrorDocument8 pagesWaco Horrorjflarah100% (1)

- The Brass Check (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study of American JournalismFrom EverandThe Brass Check (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study of American JournalismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- The Brass Check: The Most Renowned Exposé on Sensational Media Coverage and Unethical Journalism in USAFrom EverandThe Brass Check: The Most Renowned Exposé on Sensational Media Coverage and Unethical Journalism in USANo ratings yet

- The New Guard Vol 35 No 2Document30 pagesThe New Guard Vol 35 No 2The New Guard magazineNo ratings yet

- Lucifer v03 n16 December 1888Document88 pagesLucifer v03 n16 December 1888lisNo ratings yet

- Slash PDFDocument245 pagesSlash PDFJorgeNo ratings yet

- Hitler and IDocument252 pagesHitler and INat SatNo ratings yet

- Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons (Illustrated Edition): Civil War Memories SeriesFrom EverandAndersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons (Illustrated Edition): Civil War Memories SeriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- Secret and Suppressed (Banned Ideas & Hidden History) PDFDocument15 pagesSecret and Suppressed (Banned Ideas & Hidden History) PDFvickie100% (5)

- Bias Diction Syntax ExamplesDocument4 pagesBias Diction Syntax Examplesapi-252721756No ratings yet

- CP English II Unit Handout - CultureDocument1 pageCP English II Unit Handout - Cultureapi-252721756No ratings yet

- Peer Editing Workshop SheetDocument1 pagePeer Editing Workshop Sheetapi-252721756No ratings yet

- Tkam Harper Lee BioDocument3 pagesTkam Harper Lee Bioapi-252721756No ratings yet

- CP English II Unit HandoutDocument1 pageCP English II Unit Handoutapi-252721756No ratings yet

- American Lit Unit 1 HandoutDocument1 pageAmerican Lit Unit 1 Handoutapi-252721756No ratings yet

- UrlsDocument63 pagesUrlsAnonymous 5AVnoR2i9ANo ratings yet

- Fill in The Blanks TaskDocument30 pagesFill in The Blanks TaskAmy RoslizaNo ratings yet

- 9 Inverters LowDocument29 pages9 Inverters LowteslanNo ratings yet

- Price List: No Nama Barang Ukuran Harga Jual GambarDocument3 pagesPrice List: No Nama Barang Ukuran Harga Jual GambarRully MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Chopard CatRedCarpet 2013 LightDocument58 pagesChopard CatRedCarpet 2013 LightSubham GhoshNo ratings yet

- DRAFT Daisy Snow AdventureDocument9 pagesDRAFT Daisy Snow AdventureX XNo ratings yet

- Bass and Snare Drum ExercisesDocument5 pagesBass and Snare Drum ExercisesHarrisonNo ratings yet

- Install 3ds MaxDocument80 pagesInstall 3ds MaxdmoizNo ratings yet

- SCR Driving GuideDocument17 pagesSCR Driving Guidehgille14100% (2)

- Panasonic Th-42pz700u Th-50pz700u Th-58pz700u Th-50pz750u Th-58pz750u 10th Generation HD Plasma TrainingDocument116 pagesPanasonic Th-42pz700u Th-50pz700u Th-58pz700u Th-50pz750u Th-58pz750u 10th Generation HD Plasma TrainingNsb El-kathiriNo ratings yet

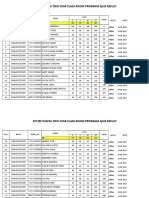

- Capstone Spring 2018 Qualifier ResultsDocument5 pagesCapstone Spring 2018 Qualifier ResultsJigmee SherpaNo ratings yet

- Invoice 1531715550Document2 pagesInvoice 1531715550Happy Stay Service Apartments ChennaiNo ratings yet

- DS 2CD2T21G0 I (S)Document5 pagesDS 2CD2T21G0 I (S)gohilnarendraNo ratings yet

- AntonymsDocument11 pagesAntonyms039 ศิริลักษณ์ อยู่สนิทNo ratings yet

- Batch Wise Quiz Test-1 ResultDocument41 pagesBatch Wise Quiz Test-1 ResultErehh JeagerNo ratings yet

- DistillationDocument10 pagesDistillationIrene De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Sets FITT Goals: Module 1-Lesson 3Document3 pagesSets FITT Goals: Module 1-Lesson 3Chum VergaraNo ratings yet

- Intel Core 14th Gen S Series Media PresentationDocument37 pagesIntel Core 14th Gen S Series Media PresentationakesplwebsiteNo ratings yet

- A Healthy Diet For Runners: Meal Plan Week 1Document4 pagesA Healthy Diet For Runners: Meal Plan Week 1ana beaverhousenNo ratings yet

- Seriale CoreeneDocument5 pagesSeriale CoreeneDaniela PîrlogNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Serv-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesMeaning of Serv-WPS Officepeter essienNo ratings yet

- Windows 7 Ultimate SP1 32 Bit LITEDocument7 pagesWindows 7 Ultimate SP1 32 Bit LITEAbu Salma WisnuNo ratings yet

- Humour VocabularyDocument1 pageHumour VocabularyDina BENHAMMOUNo ratings yet

- Milwaukee 2646 22ct E98a m18tm Cordless 2 Speed Grease Gun KitDocument3 pagesMilwaukee 2646 22ct E98a m18tm Cordless 2 Speed Grease Gun KitZeck100% (1)

- Types of Consumer ProductsDocument6 pagesTypes of Consumer ProductsMuneeb AhmedNo ratings yet

- Kumpulan Key AnswerDocument15 pagesKumpulan Key AnswerMelisa ParlinNo ratings yet

- Mountain Dog Training - How To Un-Suck Your Core WorkoutDocument14 pagesMountain Dog Training - How To Un-Suck Your Core WorkoutZacharyJonesNo ratings yet

- Unit - 2 Part II Khilji 2Document15 pagesUnit - 2 Part II Khilji 2Mutant NinjaNo ratings yet