Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

91 viewsTaking On Modern-Day Slingshots Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money by Proving The Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Taking On Modern-Day Slingshots Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money by Proving The Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Uploaded by

Steve Horn1999 profile in The Washington Post of Eric Dezenhall and Nichols-Dezenhall, the precursor of Dezenhall Resoures

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Toxic Sludge Is Good For YouDocument238 pagesToxic Sludge Is Good For Youvoip54301100% (9)

- Assignment 01Document11 pagesAssignment 01Haris AmirNo ratings yet

- NC Iii Bookkeeping ReviewerDocument18 pagesNC Iii Bookkeeping ReviewerJoseph Dhune Batoctoy100% (2)

- Institutional Sales PresentationDocument10 pagesInstitutional Sales Presentationanuj bhallaNo ratings yet

- What Is Defamation?Document6 pagesWhat Is Defamation?saule321No ratings yet

- Masters of Disaster: The Ten Commandments of Damage ControlFrom EverandMasters of Disaster: The Ten Commandments of Damage ControlRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Product Mix DecisionsDocument31 pagesProduct Mix DecisionsRajesh LambaNo ratings yet

- Industry Rockstar Become A Highly Paid High Profile Person in Your Industry 1 PDFDocument355 pagesIndustry Rockstar Become A Highly Paid High Profile Person in Your Industry 1 PDFPhillip SparksNo ratings yet

- Crisis Communication: Why Communication and Containment Are The KeyDocument2 pagesCrisis Communication: Why Communication and Containment Are The KeyYsabel Juachon0% (1)

- RP AdamDocument10 pagesRP Adamapi-315583213No ratings yet

- ProQuestDocuments 2019 03 30Document9 pagesProQuestDocuments 2019 03 30chanchunsumbrianNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetDocument91 pagesIELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetNguyễn Bình Nam50% (2)

- Mint ConditionDocument10 pagesMint ConditionKristidis WyllieNo ratings yet

- Pepsi Worst. Ad. EverDocument3 pagesPepsi Worst. Ad. EverHafsaNo ratings yet

- Subliminal AdvertisingDocument3 pagesSubliminal Advertisingmirzasuli100% (1)

- Plunder - The Crime of Our TimeDocument22 pagesPlunder - The Crime of Our TimeForeclosure FraudNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: N - RnmoDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: N - Rnmouser1No ratings yet

- Meyer Influence Mod EllDocument18 pagesMeyer Influence Mod EllBalazs SzatmariNo ratings yet

- Of Cuttlefish and MenDocument2 pagesOf Cuttlefish and MenelpadrinoleoNo ratings yet

- The Curious Person's Guide to Fighting Fake NewsFrom EverandThe Curious Person's Guide to Fighting Fake NewsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Hard and Soft NewsDocument5 pagesHard and Soft NewsFASIH YOUNASNo ratings yet

- Crystallizing Public Opinion by Edward BDocument14 pagesCrystallizing Public Opinion by Edward BTien Bui Vo ThuyNo ratings yet

- Peter Sandman - Responding To Community Outrage PDFDocument155 pagesPeter Sandman - Responding To Community Outrage PDFRon GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Jo Cox Book Review - Sept 2017Document2 pagesJo Cox Book Review - Sept 2017Sheila ChapmanNo ratings yet

- Defamation - St. FileDocument6 pagesDefamation - St. FileAmy WittavatNo ratings yet

- Reputation Matters: How to Protect Your Professional ReputationFrom EverandReputation Matters: How to Protect Your Professional ReputationNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Current DebatesDocument5 pagesFinal Paper Current DebatesContacto ProduccionesNo ratings yet

- Managed Healthcare - NOT! (Slimy Rhetoric?) : End of Life Experience WithDocument6 pagesManaged Healthcare - NOT! (Slimy Rhetoric?) : End of Life Experience WithnuckollsrNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetDocument92 pagesIELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetCold Reaper GamingNo ratings yet

- HBR - MarketingDocument2 pagesHBR - MarketingHugo LeonardoNo ratings yet

- ECONned: How Unenlightened Self Interest Undermined Democracy and Corrupted CapitalismFrom EverandECONned: How Unenlightened Self Interest Undermined Democracy and Corrupted CapitalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- Media and AdvertisingDocument4 pagesMedia and Advertisingpoiu0987No ratings yet

- Rumours PDFDocument269 pagesRumours PDFntv2000100% (1)

- A Thousand Times WorseDocument1 pageA Thousand Times WorseRichard M PattonNo ratings yet

- Your Call Is (Not That) Important to Us: Customer Service and What It Reveals About Our World and Our LivesFrom EverandYour Call Is (Not That) Important to Us: Customer Service and What It Reveals About Our World and Our LivesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Example of A Satirical EssayDocument4 pagesExample of A Satirical Essaymiwaj0pabuk2100% (2)

- RP SaraDocument6 pagesRP Saraapi-315583213No ratings yet

- 01-31-08 CD-Memo To The FBI - Expand The Probe of Economic CriDocument3 pages01-31-08 CD-Memo To The FBI - Expand The Probe of Economic CriMark WelkieNo ratings yet

- Fallacy PrezDocument12 pagesFallacy Prezapi-305354232No ratings yet

- An Ecological Critique of Global AdvertisingDocument5 pagesAn Ecological Critique of Global AdvertisingKervin PasicaranNo ratings yet

- 04moranejfall12 PDFDocument19 pages04moranejfall12 PDFmariel darkangelNo ratings yet

- This I Know: Marketing Lessons from Under the InfluenceFrom EverandThis I Know: Marketing Lessons from Under the InfluenceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Tylenol CaseStudyDocument1 pageTylenol CaseStudyMabel ChanNo ratings yet

- LSE MPP Policy Brief 20 - Fake News - FinalDocument20 pagesLSE MPP Policy Brief 20 - Fake News - FinalrameshnuvkekaNo ratings yet

- Roles of Communication in Human DevelopmentDocument6 pagesRoles of Communication in Human DevelopmentUrvashiVaidNo ratings yet

- Trial by Newswire: CommentaryDocument3 pagesTrial by Newswire: CommentarybiancabalcosNo ratings yet

- Law Chapter For Fashion JournalismDocument13 pagesLaw Chapter For Fashion JournalismRAJIV KUMARNo ratings yet

- Tone Deaf or Great MarketingDocument12 pagesTone Deaf or Great MarketingselineNo ratings yet

- Cause of Stress EssayDocument7 pagesCause of Stress Essayb725c62j100% (2)

- Alan Korwin On GunsDocument5 pagesAlan Korwin On GunsJonathan GaltNo ratings yet

- Broken Windows Thesis CriminologyDocument8 pagesBroken Windows Thesis Criminologygjhr3grk100% (1)

- Public RelationsDocument9 pagesPublic RelationsGlenda Guinto-HeweNo ratings yet

- Richard Dennis Profile On Business WeekDocument3 pagesRichard Dennis Profile On Business Weekthcm2011No ratings yet

- Ann McClintock - Propaganda 1Document4 pagesAnn McClintock - Propaganda 1JasonNo ratings yet

- What Is News?Document6 pagesWhat Is News?Alexander QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Active Marketing Strategy in Perspective: "It's So Simple, W H y Didn ? I Think of It Lvi YseirDocument4 pagesActive Marketing Strategy in Perspective: "It's So Simple, W H y Didn ? I Think of It Lvi Yseir:-*kiss youNo ratings yet

- Police Corruption EssaysDocument3 pagesPolice Corruption Essaysaaqvuknbf100% (2)

- Josh MeyerDocument8 pagesJosh MeyerJJoliatNo ratings yet

- David Einhorn Speech To Value InvestorsDocument10 pagesDavid Einhorn Speech To Value InvestorsJohn CarneyNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Political Fact CheckingDocument17 pagesThe Rise of Political Fact CheckingGlennKesslerWPNo ratings yet

- Energy in Depth - The Gas RootsDocument20 pagesEnergy in Depth - The Gas RootsJames "Chip" NorthrupNo ratings yet

- Maier Letter To Hammes Oct. 7, 1985Document1 pageMaier Letter To Hammes Oct. 7, 1985Steve HornNo ratings yet

- Dershowitz Answer To ComplaintDocument26 pagesDershowitz Answer To ComplaintSteve Horn100% (2)

- Carlos Espinosa: "Tee Up" The Putin LetterDocument23 pagesCarlos Espinosa: "Tee Up" The Putin LetterSteve HornNo ratings yet

- South Africa: U.S. Clergy Group Linked To Shell OilDocument3 pagesSouth Africa: U.S. Clergy Group Linked To Shell OilSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Michael Bishop Complaint For Declaratory Relief and Petition For Writ of MandamusDocument19 pagesMichael Bishop Complaint For Declaratory Relief and Petition For Writ of MandamusSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Carlos Espinosa TX RRC Personnel FileDocument20 pagesCarlos Espinosa TX RRC Personnel FileSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Carlos Espinosa Response To Request For Evidence On Putin ClaimsDocument30 pagesCarlos Espinosa Response To Request For Evidence On Putin ClaimsSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Petraeus Protest Arrests Press Release - 9/18/2013Document2 pagesPetraeus Protest Arrests Press Release - 9/18/2013Steve HornNo ratings yet

- PR Strategist John Mongoven DiesDocument1 pagePR Strategist John Mongoven DiesSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Ex Nestle Firm Goes BankruptDocument5 pagesEx Nestle Firm Goes BankruptSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Duchin Gets Gig at Pagan InternationalDocument3 pagesDuchin Gets Gig at Pagan InternationalSteve HornNo ratings yet

- State Response To Motion To Compel DiscoveryDocument24 pagesState Response To Motion To Compel DiscoverySteve HornNo ratings yet

- Pagan International Launch Press Release - May 1985Document2 pagesPagan International Launch Press Release - May 1985Steve HornNo ratings yet

- Rafael Pagan ObituaryDocument2 pagesRafael Pagan ObituarySteve HornNo ratings yet

- PLO Reply To State's Response To PLO Motion To Compel DiscoveryDocument21 pagesPLO Reply To State's Response To PLO Motion To Compel DiscoverySteve HornNo ratings yet

- Danny Emails About HousingDocument1 pageDanny Emails About HousingSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Trust in BanksDocument8 pagesTrust in BanksAnca IoanaNo ratings yet

- Beams Brochure Revision - FinalDocument32 pagesBeams Brochure Revision - FinalAnh VõNo ratings yet

- ME Assignment-1Document2 pagesME Assignment-1Manoj NagNo ratings yet

- MKG MKT EnvironmentDocument22 pagesMKG MKT EnvironmentTejaswiniNo ratings yet

- Pets.comDocument5 pagesPets.comphenomenon123100% (1)

- Rural Marketing Strategies - HLLDocument87 pagesRural Marketing Strategies - HLLVinay Singh100% (5)

- Financial Management Chapter 5Document40 pagesFinancial Management Chapter 5Mazni FareehaNo ratings yet

- Easy Learning of Multinational CompaniesDocument21 pagesEasy Learning of Multinational CompaniesSania AsifNo ratings yet

- AFD Guidelines V1.1Document18 pagesAFD Guidelines V1.1Peter BakkerNo ratings yet

- Business Research Methods Chapter # 1Document8 pagesBusiness Research Methods Chapter # 1Auns AzharNo ratings yet

- Goodyear Summer ProjectDocument32 pagesGoodyear Summer Projectlove tanna50% (2)

- Universal Print System LTD.: Vrushank Raut Rahul Satpute Milind Thakur Swapnil WaghDocument15 pagesUniversal Print System LTD.: Vrushank Raut Rahul Satpute Milind Thakur Swapnil WaghMilind ThakurNo ratings yet

- KuehneDocument5 pagesKuehneNoorul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Cola WarsDocument8 pagesCola WarsGr8 zaibi88% (8)

- SRM Valliammai Engineering College: Department of Management StudiesDocument11 pagesSRM Valliammai Engineering College: Department of Management StudiesArun ArunNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Axioms of Urban Economics: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument20 pagesIntroduction and Axioms of Urban Economics: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinBakhtiar RindNo ratings yet

- AMBOTDocument2 pagesAMBOTAngelyn SamandeNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature Reviewsheen100No ratings yet

- Subjective Communication: A Deep Analyst byDocument4 pagesSubjective Communication: A Deep Analyst bydoma inNo ratings yet

- VC Framework Evaluating Start Ups KaplanDocument60 pagesVC Framework Evaluating Start Ups Kaplanerigonatti9102100% (1)

- Somiya Mehta CorporateDocument2 pagesSomiya Mehta Corporateapi-345724380No ratings yet

- Assignment/ TugasanDocument10 pagesAssignment/ TugasanTATABA farmNo ratings yet

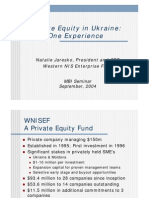

- WNISEF Experience in UkraineDocument21 pagesWNISEF Experience in UkraineVitaliy HamuhaNo ratings yet

- Reckitt BenckiserDocument9 pagesReckitt BenckiserSadaf TareenNo ratings yet

- SWOT and PEST Analysis of Southwest AirlinesDocument6 pagesSWOT and PEST Analysis of Southwest AirlinesAmmara LatifNo ratings yet

Taking On Modern-Day Slingshots Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money by Proving The Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Taking On Modern-Day Slingshots Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money by Proving The Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Uploaded by

Steve Horn0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

91 views5 pages1999 profile in The Washington Post of Eric Dezenhall and Nichols-Dezenhall, the precursor of Dezenhall Resoures

Original Title

Taking On Modern-Day Slingshots; Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money By Proving the Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1999 profile in The Washington Post of Eric Dezenhall and Nichols-Dezenhall, the precursor of Dezenhall Resoures

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

91 views5 pagesTaking On Modern-Day Slingshots Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money by Proving The Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Taking On Modern-Day Slingshots Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money by Proving The Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Uploaded by

Steve Horn1999 profile in The Washington Post of Eric Dezenhall and Nichols-Dezenhall, the precursor of Dezenhall Resoures

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 5

The Washington Post

October 25, 1999, Monday, Final Edition

Taking On Modern-Day Slingshots; Eric Dezenhall's PR Firm Makes Its Money By Proving the

Little Guy Isn't Always Right

Dwight Thompson, Washington Post Staff Writer

"Sometimes," says Eric Dezenhall, "you have to ght the altar boy.

For even altar boys can be wrong, and woe to the one who attacks any of Dezenhall's clients.

Dezenhall is a crusader against the crusaders and a defender of the defenseless. He's one of

the PR industry's premier practitioners of "crisis management," the art and craft of countering

public attacks on corporations and celebrities, and mitigating the damage from misbehavior,

malfeasance and various other blunders.

Dezenhall, co-founder of Nichols Dezenhall Communications Management Group Ltd., a highly

specialized and highly compensated public relations practice in Washington, concentrates on

acking for the bad guy, operating under the premise that the good guy is often wrong.

Dezenhall explains his innate suspicion of moralistic attacks by citing the example of the late

Chicago prelate Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, who was accused of molestation by a former

seminary student in 1993. The attack, widely covered in the media, demolished Bernadin's

reputation and did not stop until Bernadin's lawyers took aggressive action and disproved the

accusation.

"That's what modern crisis management is often about," Dezenhall said. "Fighting altar boys."

'The Culture of the Attack

A relatively new spur of the public relations profession, crisis management is located at the

extreme end of the PR continuum and grows larger every day. Dezenhall, 37, whose rm was

founded in 1987 with partner Nick Nichols, his former boss at Porter Novelli, describes his

business as a response to what he calls "the culture of the attack.

"Our rm really started to grow when attack journalism exploded, as the rules of decorum in our

culture declined as to what questions can be asked and the hackneyed, gentlemanly response

didn't get results," he said. "If it weren't for these things, I'd be sleeping on a grate somewhere."

Most public relations businesses are headquartered in New York, with mere satellite ofces

here. But Washington is the very nexus of the crisis communications business. With its

concentration of government, regulatory agencies and trade and industry associations, the city

has "become the center of the crisis-management universe," according to Ben Long, president

of Travaille Executive Search, a rm that specializes in recruiting PR professionals.

Dezenhall and others who practice crisis management say its methods are distinctly different

from those of what most people consider public relations. Whereas another PR rm might try to

persuade the public that a client isn't wrong, or at least isn't so bad, a crisis manager's sole

purpose is to stop the attack by whatever means necessary.

As Dezenhall puts it, "when there's a knife at your throat, you've got more than an image

problem."

Dezenhall tends to get hired when another PR rm has gotten red. "We are the last resort, the

Navy SEALs of the communications business," he said. "Our only objective is to make the

problem go away. We don't want to schmooze or be your friend.

Described by Doug Elmets, his former boss from the Reagan White House's Ofce of

Communications, as "a dog with a bone when it comes to attacks," Dezenhall's outward

appearance belies his reputation. He could be any thirtysomething tech executive or lawyer, an

avid runner who is as comfortable with casual Fridays as with coaching his son's Little League

team.

"When a 10-year-old kid says, 'Gee, Mr. Dezenhall, you could use some Rogaine,' it really

keeps you down to earth," he said.

But both his former boss and his former clients describe him as the man whom, in battle, they

would want the most in their foxhole. Jean Statler, who in 1988, as vice president of

communications at the American Plastics Council, hired Nichols Dezenhall instead of a

mainstream PR rm to help deect environmentalists' attacks, describes him as "the best in the

business.

He rarely shows up on the public's radar, only occasionally speaking for his clients. He prefers

to work in the background. He won't name his clients, though a search of press coverage of PR

conagrations produced some clues. In 1988, he worked for Avtex Fibers, the nation's largest

rayon manufacturer, when it was accused of contaminating drinking water in Front Royal by

dumping hazardous chemicals into unlined pits. He also represented the National Polystyrene

Recycling Co. when McDonald's stopped wrapping its burgers in the material in 1990. And,

more recently, in 1997 he represented Arco Chemical Co. in that rm's battle to keep MTBE, a

petroleum additive designed to reduce air pollution, on the market after environmentalists in

California attacked it as a ground polluter.

Dezenhall won't talk about specic cases involving named clients, but it's clear that the above

cases were relatively low-key compared with some of the work he has done.

The methods used by his rm are relatively straightforward and, to the chagrin of PR rms

everywhere, nakedly free of spin. Nichols Dezenhall employs, among other people, a small

arsenal of ex-law enforcement personnel and investigative reporters; their rst step is to

"effectively do our own investigative stories on our own clients to determine what the truth is,"

he said. "In a situation where it's litigory, regulatory or a 'Dateline NBC' type of thing, we nd out

everything we possibly can about the merits of the story. If we believe the accusation is wrong,

we will use media resources, legal, regulatory, governmental -- anything we can do to make it

harder to consummate that attack.

He did talk about one case that he worked on. A popular TV magazine show was about to run

with a story alleging that employees of a hotel chain were routinely "peeping" upon their guests

through a man-made hole in the wall. After having forensic experts disassemble the hotel room

in question, the Nichols Dezenhall team determined that the telltale hole didn't go all the way

through, rendering it impossible for anyone to peep on anything. The rm's legal experts also

determined that the supposed perpetrators had a track record of extortion and using the media

in their scams. The story never ran.

Dezenhall and those like him approach each case with one thought in mind, one that is often at

odds with PR's marketing roots: The public isn't always right.

Take the time when a supermarket tabloid paid an ex-ight attendant $ 75,000 to tape a sexual

liaison with sports announcer Frank Gifford, a classic case of Dezenhall's "culture of attack."

Dezenhall's book, "Nail 'Em!," published this year, describes in great detail what he sees as a

surging tide of such cases in which individuals prot by accusing or disgracing prominent

individuals and corporations.

Of course, consumer-rights and environmental groups don't often view crisis managers as the

guardians of truth. Jeremiah Baumann of the U.S. Public Interest Research Group characterizes

them as "just another means that industry uses to mask their irresponsibility. It mirrors actions

taken on Capitol Hill to undermine the public's right to know about toxic pollution and other

environmental problems.

Consumer advocate Ralph Nader makes a more blanket condemnation. "They'll use any tool

they can to minimize the damage and paper over the mistakes of industry and precipitous

legislation," he said.

Turning the Tables

Dezenhall's tack is to turn the tables, essentially attacking the attackers, with the goal of making

it too costly for them to continue to assail his client. Conversely, if the accusation is justied --

say a client did egregiously dump toxic waste or bed a teenage babysitter -- his advice is

simple: Repent, show as much remorse as possible, and try to rectify the problem as quickly as

you can. This is hard medicine for many clients to swallow, but Dezenhall refuses to counsel

otherwise.

He said that compared with a dozen years ago, fewer of his clients are as guilty as their

accusers say they are -- which makes it easier for him to be righteously indignant in their

defense. Dezenhall says he sleeps soundly at night, one reason being that he won't lie or

condone lying in any instance. He said he repeatedly turns down all tobacco, rearms and

abortion work on both sides of those issues.

Paying close attention to both the media and business cycles aids his efforts to stop attacks in

their tracks. Depending on the market, certain products are particularly vulnerable to assault --

gas-guzzling, heavy-polluting sport-utility vehicles in an oil crisis, for example. By timing both the

economic and media cycles, determining when the media will have saturated the airwaves and

newsstands with a story to the point where no one wants to hear about it anymore, Dezenhall is

able to counterattack most effectively.

Dezenhall cites the case of another of his former clients, the maker of a food ingredient that an

activist group and a doctor had claimed was hazardous. In the course of Dezenhall's

investigation, he was able to ascertain several key facts: "Number one, the doctor had been

short-selling the stock in the client's company and, number two, that the activist group was

actually manufactured by [a] competitor.

"Well, the fact was these people were corrupt. But the cultural prejudice against businesses is

so intense that the attacks on them are viewed as victimless. And their defenses are viewed by

the very fact that they have the temerity to defend themselves, as being an extension of some

kind of Nixon White House thing.

His formula for effective response boils down to switching around the traditional roles the media

assign to groups and individuals during a story. For example, while the story above might

initially portray the food ingredient manufacturer as the villain, the public as the victim and the

activist group as the vindicator, Dezenhall presents the manufacturer as the real victim, the

activist group as the villain and the public as the vindicator. And, he said, nothing sells better

than showing the public how it has been hoodwinked.

Stars in a Growing Field

Dezenhall said he gets most of his clients from word of mouth. While there is plenty of

competition for the work, jobs typically aren't put out to bid in the way of traditional PR or

advertising contracts. The types of companies that seek crisis management are varied, but the

majority are clustered in the chemical, petrochemical, pharmaceutical and automotive

industries.

Another crisis-management rm in Washington with brand-name recognition is Rowen & Blewitt

Inc., recently acquired by the communications giant Shandwick International as its exclusive

crisis-management department. Understanding the business from the inside out, partner Ford

Rowen is a former NBC correspondent who covered environmental topics such as the Three

Mile Island incident. Co-partner Rick Blewitt came from a more traditional PR background, doing

most of his work for chemical companies.

Indeed, the eld is increasingly crowded. Crisis management is rapidly taking off, and most of

the major public relations rms now advertise at least some expertise in the eld. Only a few

rms, however, are like Nichols Dezenhall, strictly specialists in crisis management. For the

broader public relations rms, crisis management tends to consist mainly of preparing for crises,

training the top tier of executives in a company how to react during a crisis and how to avoid

crises in the rst place.

For instance, Ogilvy Public Relations calls its service "brand shielding," while other rms such

as the Ammerman Experience specialize exclusively in crisis training -- training CEOs and other

executives in how to deal with attacks should they come.

As Ben Long of Travaille Executive Search points out, "crisis management hasn't even begun to

fully realize the potential of the market and is just now starting to wander outside of the

Beltway.

Which for Eric Dezenhall means one thing: more people to ght back against, even if they're

altar boys.

Attack, Counterattack

Some well-known "crisis management" cases:

* "Dateline NBC's" truck explosion expose, 1992

When the prime-time news program showed GM truck gas tanks exploding in a crash test, the

car company was able to prove the event was staged with explosive devices.

* Exxon Valdez, 1989

Company executives' two-week delay in visiting Prince William Sound, Alaska, after the accident

damaged the public's perception of Exxon, feeding the impressions of an unfeeling corporate

giant.

* ValuJet Florida crash, 1996

The company was so badly tarnished by its poor safety record that it changed its name,

remaining in business as AirTran.

You might also like

- Toxic Sludge Is Good For YouDocument238 pagesToxic Sludge Is Good For Youvoip54301100% (9)

- Assignment 01Document11 pagesAssignment 01Haris AmirNo ratings yet

- NC Iii Bookkeeping ReviewerDocument18 pagesNC Iii Bookkeeping ReviewerJoseph Dhune Batoctoy100% (2)

- Institutional Sales PresentationDocument10 pagesInstitutional Sales Presentationanuj bhallaNo ratings yet

- What Is Defamation?Document6 pagesWhat Is Defamation?saule321No ratings yet

- Masters of Disaster: The Ten Commandments of Damage ControlFrom EverandMasters of Disaster: The Ten Commandments of Damage ControlRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Product Mix DecisionsDocument31 pagesProduct Mix DecisionsRajesh LambaNo ratings yet

- Industry Rockstar Become A Highly Paid High Profile Person in Your Industry 1 PDFDocument355 pagesIndustry Rockstar Become A Highly Paid High Profile Person in Your Industry 1 PDFPhillip SparksNo ratings yet

- Crisis Communication: Why Communication and Containment Are The KeyDocument2 pagesCrisis Communication: Why Communication and Containment Are The KeyYsabel Juachon0% (1)

- RP AdamDocument10 pagesRP Adamapi-315583213No ratings yet

- ProQuestDocuments 2019 03 30Document9 pagesProQuestDocuments 2019 03 30chanchunsumbrianNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetDocument91 pagesIELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetNguyễn Bình Nam50% (2)

- Mint ConditionDocument10 pagesMint ConditionKristidis WyllieNo ratings yet

- Pepsi Worst. Ad. EverDocument3 pagesPepsi Worst. Ad. EverHafsaNo ratings yet

- Subliminal AdvertisingDocument3 pagesSubliminal Advertisingmirzasuli100% (1)

- Plunder - The Crime of Our TimeDocument22 pagesPlunder - The Crime of Our TimeForeclosure FraudNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: N - RnmoDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: N - Rnmouser1No ratings yet

- Meyer Influence Mod EllDocument18 pagesMeyer Influence Mod EllBalazs SzatmariNo ratings yet

- Of Cuttlefish and MenDocument2 pagesOf Cuttlefish and MenelpadrinoleoNo ratings yet

- The Curious Person's Guide to Fighting Fake NewsFrom EverandThe Curious Person's Guide to Fighting Fake NewsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Hard and Soft NewsDocument5 pagesHard and Soft NewsFASIH YOUNASNo ratings yet

- Crystallizing Public Opinion by Edward BDocument14 pagesCrystallizing Public Opinion by Edward BTien Bui Vo ThuyNo ratings yet

- Peter Sandman - Responding To Community Outrage PDFDocument155 pagesPeter Sandman - Responding To Community Outrage PDFRon GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Jo Cox Book Review - Sept 2017Document2 pagesJo Cox Book Review - Sept 2017Sheila ChapmanNo ratings yet

- Defamation - St. FileDocument6 pagesDefamation - St. FileAmy WittavatNo ratings yet

- Reputation Matters: How to Protect Your Professional ReputationFrom EverandReputation Matters: How to Protect Your Professional ReputationNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Current DebatesDocument5 pagesFinal Paper Current DebatesContacto ProduccionesNo ratings yet

- Managed Healthcare - NOT! (Slimy Rhetoric?) : End of Life Experience WithDocument6 pagesManaged Healthcare - NOT! (Slimy Rhetoric?) : End of Life Experience WithnuckollsrNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetDocument92 pagesIELTS Reading Practice 1 (Academic) Time Allowed: 1 Hour Number of Questions: 40 Instructions All Answers Must Be Written On The Answer SheetCold Reaper GamingNo ratings yet

- HBR - MarketingDocument2 pagesHBR - MarketingHugo LeonardoNo ratings yet

- ECONned: How Unenlightened Self Interest Undermined Democracy and Corrupted CapitalismFrom EverandECONned: How Unenlightened Self Interest Undermined Democracy and Corrupted CapitalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- Media and AdvertisingDocument4 pagesMedia and Advertisingpoiu0987No ratings yet

- Rumours PDFDocument269 pagesRumours PDFntv2000100% (1)

- A Thousand Times WorseDocument1 pageA Thousand Times WorseRichard M PattonNo ratings yet

- Your Call Is (Not That) Important to Us: Customer Service and What It Reveals About Our World and Our LivesFrom EverandYour Call Is (Not That) Important to Us: Customer Service and What It Reveals About Our World and Our LivesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Example of A Satirical EssayDocument4 pagesExample of A Satirical Essaymiwaj0pabuk2100% (2)

- RP SaraDocument6 pagesRP Saraapi-315583213No ratings yet

- 01-31-08 CD-Memo To The FBI - Expand The Probe of Economic CriDocument3 pages01-31-08 CD-Memo To The FBI - Expand The Probe of Economic CriMark WelkieNo ratings yet

- Fallacy PrezDocument12 pagesFallacy Prezapi-305354232No ratings yet

- An Ecological Critique of Global AdvertisingDocument5 pagesAn Ecological Critique of Global AdvertisingKervin PasicaranNo ratings yet

- 04moranejfall12 PDFDocument19 pages04moranejfall12 PDFmariel darkangelNo ratings yet

- This I Know: Marketing Lessons from Under the InfluenceFrom EverandThis I Know: Marketing Lessons from Under the InfluenceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Tylenol CaseStudyDocument1 pageTylenol CaseStudyMabel ChanNo ratings yet

- LSE MPP Policy Brief 20 - Fake News - FinalDocument20 pagesLSE MPP Policy Brief 20 - Fake News - FinalrameshnuvkekaNo ratings yet

- Roles of Communication in Human DevelopmentDocument6 pagesRoles of Communication in Human DevelopmentUrvashiVaidNo ratings yet

- Trial by Newswire: CommentaryDocument3 pagesTrial by Newswire: CommentarybiancabalcosNo ratings yet

- Law Chapter For Fashion JournalismDocument13 pagesLaw Chapter For Fashion JournalismRAJIV KUMARNo ratings yet

- Tone Deaf or Great MarketingDocument12 pagesTone Deaf or Great MarketingselineNo ratings yet

- Cause of Stress EssayDocument7 pagesCause of Stress Essayb725c62j100% (2)

- Alan Korwin On GunsDocument5 pagesAlan Korwin On GunsJonathan GaltNo ratings yet

- Broken Windows Thesis CriminologyDocument8 pagesBroken Windows Thesis Criminologygjhr3grk100% (1)

- Public RelationsDocument9 pagesPublic RelationsGlenda Guinto-HeweNo ratings yet

- Richard Dennis Profile On Business WeekDocument3 pagesRichard Dennis Profile On Business Weekthcm2011No ratings yet

- Ann McClintock - Propaganda 1Document4 pagesAnn McClintock - Propaganda 1JasonNo ratings yet

- What Is News?Document6 pagesWhat Is News?Alexander QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Active Marketing Strategy in Perspective: "It's So Simple, W H y Didn ? I Think of It Lvi YseirDocument4 pagesActive Marketing Strategy in Perspective: "It's So Simple, W H y Didn ? I Think of It Lvi Yseir:-*kiss youNo ratings yet

- Police Corruption EssaysDocument3 pagesPolice Corruption Essaysaaqvuknbf100% (2)

- Josh MeyerDocument8 pagesJosh MeyerJJoliatNo ratings yet

- David Einhorn Speech To Value InvestorsDocument10 pagesDavid Einhorn Speech To Value InvestorsJohn CarneyNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Political Fact CheckingDocument17 pagesThe Rise of Political Fact CheckingGlennKesslerWPNo ratings yet

- Energy in Depth - The Gas RootsDocument20 pagesEnergy in Depth - The Gas RootsJames "Chip" NorthrupNo ratings yet

- Maier Letter To Hammes Oct. 7, 1985Document1 pageMaier Letter To Hammes Oct. 7, 1985Steve HornNo ratings yet

- Dershowitz Answer To ComplaintDocument26 pagesDershowitz Answer To ComplaintSteve Horn100% (2)

- Carlos Espinosa: "Tee Up" The Putin LetterDocument23 pagesCarlos Espinosa: "Tee Up" The Putin LetterSteve HornNo ratings yet

- South Africa: U.S. Clergy Group Linked To Shell OilDocument3 pagesSouth Africa: U.S. Clergy Group Linked To Shell OilSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Michael Bishop Complaint For Declaratory Relief and Petition For Writ of MandamusDocument19 pagesMichael Bishop Complaint For Declaratory Relief and Petition For Writ of MandamusSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Carlos Espinosa TX RRC Personnel FileDocument20 pagesCarlos Espinosa TX RRC Personnel FileSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Carlos Espinosa Response To Request For Evidence On Putin ClaimsDocument30 pagesCarlos Espinosa Response To Request For Evidence On Putin ClaimsSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Petraeus Protest Arrests Press Release - 9/18/2013Document2 pagesPetraeus Protest Arrests Press Release - 9/18/2013Steve HornNo ratings yet

- PR Strategist John Mongoven DiesDocument1 pagePR Strategist John Mongoven DiesSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Ex Nestle Firm Goes BankruptDocument5 pagesEx Nestle Firm Goes BankruptSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Duchin Gets Gig at Pagan InternationalDocument3 pagesDuchin Gets Gig at Pagan InternationalSteve HornNo ratings yet

- State Response To Motion To Compel DiscoveryDocument24 pagesState Response To Motion To Compel DiscoverySteve HornNo ratings yet

- Pagan International Launch Press Release - May 1985Document2 pagesPagan International Launch Press Release - May 1985Steve HornNo ratings yet

- Rafael Pagan ObituaryDocument2 pagesRafael Pagan ObituarySteve HornNo ratings yet

- PLO Reply To State's Response To PLO Motion To Compel DiscoveryDocument21 pagesPLO Reply To State's Response To PLO Motion To Compel DiscoverySteve HornNo ratings yet

- Danny Emails About HousingDocument1 pageDanny Emails About HousingSteve HornNo ratings yet

- Trust in BanksDocument8 pagesTrust in BanksAnca IoanaNo ratings yet

- Beams Brochure Revision - FinalDocument32 pagesBeams Brochure Revision - FinalAnh VõNo ratings yet

- ME Assignment-1Document2 pagesME Assignment-1Manoj NagNo ratings yet

- MKG MKT EnvironmentDocument22 pagesMKG MKT EnvironmentTejaswiniNo ratings yet

- Pets.comDocument5 pagesPets.comphenomenon123100% (1)

- Rural Marketing Strategies - HLLDocument87 pagesRural Marketing Strategies - HLLVinay Singh100% (5)

- Financial Management Chapter 5Document40 pagesFinancial Management Chapter 5Mazni FareehaNo ratings yet

- Easy Learning of Multinational CompaniesDocument21 pagesEasy Learning of Multinational CompaniesSania AsifNo ratings yet

- AFD Guidelines V1.1Document18 pagesAFD Guidelines V1.1Peter BakkerNo ratings yet

- Business Research Methods Chapter # 1Document8 pagesBusiness Research Methods Chapter # 1Auns AzharNo ratings yet

- Goodyear Summer ProjectDocument32 pagesGoodyear Summer Projectlove tanna50% (2)

- Universal Print System LTD.: Vrushank Raut Rahul Satpute Milind Thakur Swapnil WaghDocument15 pagesUniversal Print System LTD.: Vrushank Raut Rahul Satpute Milind Thakur Swapnil WaghMilind ThakurNo ratings yet

- KuehneDocument5 pagesKuehneNoorul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Cola WarsDocument8 pagesCola WarsGr8 zaibi88% (8)

- SRM Valliammai Engineering College: Department of Management StudiesDocument11 pagesSRM Valliammai Engineering College: Department of Management StudiesArun ArunNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Axioms of Urban Economics: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument20 pagesIntroduction and Axioms of Urban Economics: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinBakhtiar RindNo ratings yet

- AMBOTDocument2 pagesAMBOTAngelyn SamandeNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature Reviewsheen100No ratings yet

- Subjective Communication: A Deep Analyst byDocument4 pagesSubjective Communication: A Deep Analyst bydoma inNo ratings yet

- VC Framework Evaluating Start Ups KaplanDocument60 pagesVC Framework Evaluating Start Ups Kaplanerigonatti9102100% (1)

- Somiya Mehta CorporateDocument2 pagesSomiya Mehta Corporateapi-345724380No ratings yet

- Assignment/ TugasanDocument10 pagesAssignment/ TugasanTATABA farmNo ratings yet

- WNISEF Experience in UkraineDocument21 pagesWNISEF Experience in UkraineVitaliy HamuhaNo ratings yet

- Reckitt BenckiserDocument9 pagesReckitt BenckiserSadaf TareenNo ratings yet

- SWOT and PEST Analysis of Southwest AirlinesDocument6 pagesSWOT and PEST Analysis of Southwest AirlinesAmmara LatifNo ratings yet