Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transpo Day 2 Cases

Transpo Day 2 Cases

Uploaded by

Jasmin AlapagCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transpo Day 2 Cases

Transpo Day 2 Cases

Uploaded by

Jasmin AlapagCopyright:

Available Formats

Ganzon vs.

CA

Petitioner Ganzon failed to show that the loss of the scrap iron due to any cause enumerated in Art. 1734.

The order of the acting Mayor did not constitute valid authority for petitioner to carry out. In any case, the intervention

of the municipal officials was not of a character that would render impossible the fulfillment by the carrier of its

obligation. The petitioner was not duly bound to obey the illegal order to dump into the sea the scrap of iron.

Moreover, there is absence of sufficient proof that the issuance of the same order was attended with such force or

intimidation as to completely overpower the will of the petitioners employees.

By the delivery made during Dec. 1, 1956, the scraps were unconditionally placed in the possession and

control of the common carrier, and upon their receipt by the carrier of transportation, the contract of carriage was

deemed perfected. Consequently, Ganzons extraordinary responsibility for the loss, destruction or deterioration of

the goods commenced. According to Art 1738, such extraordinary responsibility would cease only upon the delivery

by the carrier to the consignee or persons with right to receive them. The fact that part of the shipment had not been

loaded on board did not impair the contract of transportation as the goods remained in the custody & control of the

carrier.

Maranan vs. Perez

The basis of the common carrier's liability under NCC for assaults on passengers committed by its drivers

rests either on (1) the doctrine of respondeat superior or (2) the principle that it is the carrier's implied duty to

transport the passenger safely.

Under the first, which is the minority view, the carrier is liable only when the act of the employee is within the

scope of his authority and duty. It is not sufficient that the act be within the course of employment only. Under the

second view, upheld by the majority and also by the later cases, it is enough that the assault happens within the

course of the employee's duty. It is no defense for the carrier that the act was done in excess of authority or in

disobedience of the carrier's orders. The carrier's liability here is absolute in the sense that it practically secures the

passengers from assaults committed by its own employees. Art. 1759, evidently follows the rule based on the second

view.

Accordingly, it is the carrier's strict obligation to select its drivers and similar employees with due regard not

only to their technical competence and physical ability, but also, no less important, to their total personality, including

their patterns of behavior, moral fibers, and social attitude.

Bachelor Express Inc vs. CA

The running amuck of the passenger was the proximate cause of the incident as it triggered off a commotion

and panic among the passengers such that the passengers started running to the sole exit shoving each other

resulting in the falling off the bus by passengers Beter and Rautraut causing them fatal injuries. The sudden act of

the passenger who stabbed another passenger in the bus is within the context of force majeure. However, in order

that a common carrier may be absolved from liability in case of force majeure, it is not enough that the accident was

caused by force majeure. The common carrier must still prove that it was not negligent in causing the injuries

resulting from such accident. In this case, Bachelor was negligent.

Considering the factual findings of the Court of Appeals-the bus driver did not immediately stop the bus at

the height of the commotion; the bus was speeding from a full stop; the victims fell from the bus door when it was

opened or gave way while the bus was still running; the conductor panicked and blew his whistle after people had

already fallen off the bus; and the bus was not properly equipped with doors in accordance with law.

Sarkies Tours Phils vs. Court of Appeals

Under the Civil Code, common carriers, from the nature of their business and for reasons of public policy,

are bound to observe extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods transported by them, and this liability

lasts from the time the goods are unconditionally placed in the possession of, and received by the carrier for

transportation until the same are delivered, actually or constructively, by the carrier to the person who has a right to

receive them, unless the loss is due to any of the excepted causes under Article 1734 thereof.

Where the common carrier accepted its passenger's baggage for transportation and even had it placed in

the vehicle by its own employee, its failure to collect the freight charge is the common carrier's own lookout. It is

responsible for the consequent loss of the baggage. In the instant case, defendant appellant's employee even helped

Fatima Minerva Fortades and her brother load the luggages/baggages in the bus' baggage compartment, without

asking that they be weighed, declared, receipted or paid for. Neither was this required of the other passengers.

Phil. Rabbit Bus Lines vs. IAC

The principle about "the last clear" chance, would call for application in a suit between the owners and

drivers of the two colliding vehicles. It does not arise where a passenger demands responsibility from the carrier to

enforce its contractual obligations. For it would be inequitable to exempt the negligent driver of the jeepney and its

owners on the ground that the other driver was likewise guilty of negligence."

It is the rule under the substantial factor test that if the actor's conduct is a substantial factor in bringing

about harm to another, the fact that the actor neither foresaw nor should have foreseen the extent of the harm or the

manner in which it occurred does not prevent him from being liable. The bus driver's conduct is not a substantial

factor in bringing about harm to the passengers of the jeepney. It cannot be said that the bus was travelling at a fast

speed when the accident occurred because the speed of 80 to 90 kilometers per hour, assuming such calculation to

be correct, is yet within the speed limit allowed in highways.

Japan Airlines vs. CA

Accordingly, there is no question that when a party is unable to fulfill his obligation because of "force

majeure," the general rule is that he cannot be held liable for damages for non-performance. Corollarily, when JAL

was prevented from resuming its flight to Manila due to the effects of Mt. Pinatubo eruption, whatever losses or

damages in the form of hotel and meal expenses the stranded passengers incurred, cannot be charged to JAL. Yet it

is undeniable that JAL assumed the hotel expenses of respondents for their unexpected overnight stay on June 15,

1991.

It has been held that airline passengers must take such risks incident to the mode of travel. In this regard,

adverse weather conditions or extreme climatic changes are some of the perils involved in air travel, the

consequences of which the passenger must assume or expect.

While JAL was no longer required to defray private respondents' living expenses during their stay in Narita

on account of the fortuitous event, JAL had the duty to make the necessary arrangements to transport private

respondents on the first available connecting flight to Manila. Petitioner JAL reneged on its obligation to look after the

comfort and convenience of its passengers when it declassified private respondents from "transit passengers" to

"new passengers" as a result of which private respondents were obliged to make the necessary arrangements

themselves for the next flight to Manila.

GANZON vs. CA

Facts: In 1965, private respondent Tumambing contracted the services of petitioner Ganzon to haul 305 tons of

scrap iron from Mariveles, Bataan on board the latters lighter. Pursuant to their agreement, private respondent

delivered the scrap iron to the captain for loading.

When half of the scrap iron was loaded, Mayor Advincula demanded P5,000.00 from private respondents,

which the latter refused to give, prompting the Mayor to draw his gun and shoot at him. The gunshot was not fatal but

he had to be taken to a hospital.

Thereafter, the loading of the scrap iron was resumed. The Acting Mayor, accompanied by three policemen,

ordered the captain and his crew to dump the scrap iron, with the rest brought to Nassco Compound. A receipt was

issued stating that the Municipality of Mariveles had taken custody of the scrap iron.

Issue: Whether or not petitioner is guilty of breach of contract of transportation and in imposing a liability against him

commencing from the time the scrap iron was placed in his custody and control have no basis in fact and in law.

Held: Yes, petitioner is guilty of breach of the contract of transportation. By the said act of delivery, the scraps were

unconditionally placed in the possession and control of the common carrier, and upon their receipt by the carrier for

transportation, the contract of carriage was deemed perfected. Consequently, the petitioner- carriers extraordinary

responsibility for the loss, destruction or deterioration of the goods commenced. Pursuant to Article 1736, such

extraordinary responsibility would cease only upon the delivery, actual or constructive, by the carrier to the

consignee, or to the person who has a right to receive them. The fact that part of the shipment had not been headed

the lighter did not impair the said contract of transportation as the goods remained in the custody and control of the

carrier, albeit still unloaded.

The Court ruled that the petition is DENIED.

MARANAN vs. PEREZ

Facts: Rogelio Corachea, on October 18, 1960, was a passenger in a taxicab owned and operated by Pascual Perez

when he was stabbed and killed by the driver, Simeon Valenzuela. Valenzuela was prosecuted for homicide in the

Court of First Instance of Batangas and was found guilty. While appeal was pending in the Court of Appeals, Antonia

Maranan, Rogelio's mother, filed an action to recover damages. The court decided in plaintiffs favor. Hence the

instant petition.

Issue: Whether or not defendant- operators could be held liable for damages

Held: Yes. Defendant-appellant relies solely on the ruling enunciated in Gillaco v. Manila Railroad Co., 97 Phil. 884,

that the carrier is under no absolute liability for assaults of its employees upon the passengers. The attendant facts

and controlling law of that case and the one at bar are very different however. In the Gillaco case, the passenger was

killed outside the scope and the course of duty of the guilty employee. Now here, the killing was perpetrated by the

driver of the very cab transporting the passenger, in whose hands the carrier had entrusted the duty of executing the

contract of carriage. In other words, unlike the Gillaco case, the killing of the passenger here took place in the course

of duty of the guilty employee and when the employee was acting within the scope of his duties.

Moreover, the Gillaco case was decided under the provisions of the Civil Code of 1889 which, unlike the

present Civil Code, did not impose upon common carriers absolute liability for the safety of passengers against wilful

assaults or negligent acts committed by their employees. The death of the passenger in the Gillaco case was truly a

fortuitous event which exempted the carrier from liability.

The Civil Code provisions on the subject of Common Carriers are new and were taken from Anglo-American

Law. There, the basis of the carrier's liability for assaults on passengers committed by its drivers rests either on (1)

the doctrine of respondeat superior or (2) the principle that it is the carrier's implied duty to transport the passenger

safely.

Under the first, which is the minority view, the carrier is liable only when the act of the employee is within the

scope of his authority and duty. It is not sufficient that the act be within the course of employment only. Under the

second view, upheld by the majority and also by the later cases, it is enough that the assault happens within the

course of the employee's duty. It is no defense for the carrier that the act was done in excess of authority or in

disobedience of the carrier's orders. The carrier's liability here is absolute in the sense that it practically secures the

passengers from assaults committed by its own employees. As can be gleaned from Art. 1759, the Civil Code of the

Philippines evidently follows the rule based on the second view. At least three very cogent reasons underlie this rule.

(1) the special undertaking of the carrier requires that it furnish its passenger that full measure of protection afforded

by the exercise of the high degree of care prescribed by the law, inter alia from violence and insults at the hands of

strangers and other passengers, but above all, from the acts of the carrier's own servants charged with the

passenger's safety; (2) said liability of the carrier for the servant's violation of duty to passengers, is the result of the

formers confiding in the servant's hands the performance of his contract to safely transport the passenger, delegating

therewith the duty of protecting the passenger with the utmost care prescribed by law; and (3) as between the carrier

and the passenger, the former must bear the risk of wrongful acts or negligence of the carrier's employees against

passengers, since it, and not the passengers, has power to select and remove them.

Accordingly, it is the carrier's strict obligation to select its drivers and similar employees with due regard not

only to their technical competence and physical ability, but also, no less important, to their total personality, including

their patterns of behavior, moral fibers, and social attitude.

Applying this stringent norm to the facts in this case, therefore, the lower court rightly adjudged the

defendant carrier liable pursuant to Art. 1759 of the Civil Code. The dismissal of the claim against the defendant

driver was also correct. Plaintiff's action was predicated on breach of contract of carriage7 and the cab driver was not

a party thereto. His civil liability is covered in the criminal case wherein he was convicted by final judgment.

BACHELOR EXPRESS, vs.CA

Facts: The bus owned by Petitioners came from Davao City on its way to Cagayan de Oro City passing Butuan City.

While at Tabon-Tabon, Butuan City, the bus picked up a passenger, that about fifteen minutes later, a passenger at

the rear portion suddenly stabbed a PC soldier which caused commotion and panic among the passengers. When

the bus stopped, passengers Ornominio Beter and Narcisa Rautraut were found lying down the road, the former

already dead as a result of head injuries and the latter also suffering from severe injuries which caused her death

later. The passenger assailant alighted from the bus and ran toward the bushes but was killed by the police.

Thereafter, the heirs of Ornominio Beter and Narcisa Rautraut, private respondents herein filed a complaint for "sum

of money" against Bachelor Express, Inc., its alleged owner and the driver Rivera. The lower court dismissed the

complaint. CA reversed the decision, hence the instant petition.

Issue: Whether or not petitioner is negligent.

Held: Yes. The liability, if any, of the petitioners is anchored on culpa contractual or breach of contract of carriage.

Art. 1732, 1733, 1755 and 1756 are applicable. There is no question that Bachelor is a common carrier. Hence,

Bachelor is bound to carry its passengers safely as far as human care and foresight can provide using the utmost

diligence of very cautious persons, with a due regard for all the circumstances. In the case at bar, Ornominio Beter

and Narcisa Rautraut were passengers of a bus belonging to Bachelor and, while passengers of the bus, suffered

injuries which caused their death. Consequently, pursuant to Article 1756 of the Civil Code, Bachelor is presumed to

have acted negligently unless it can prove that it had observed extraordinary diligence in accordance with Articles

1733 and 1755 of the New Civil Code.

Bachelor denies liability for the death of Beter and Rautraut in that their death was caused by a third person

who was beyond its control and supervision. In effect, the petitioner, in order to overcome the presumption of fault or

negligence under the law, states that the vehicular incident resulting in the death of passengers Beter and Rautraut

was caused by force majeure or caso fortuito over which the common carrier did not have any control. The running

amuck of the passenger was the proximate cause of the incident as it triggered off a commotion and panic among the

passengers such that the passengers started running to the sole exit shoving each other resulting in the falling off the

bus by passengers Beter and Rautraut causing them fatal injuries. The sudden act of the passenger who stabbed

another passenger in the bus is within the context of force majeure. However, in order that a common carrier may be

absolved from liability in case of force majeure, it is not enough that the accident was caused by force majeure. The

common carrier must still prove that it was not negligent in causing the injuries resulting from such accident. In this

case, Bachelor was negligent.

Considering the factual findings of the Court of Appeals-the bus driver did not immediately stop the bus at

the height of the commotion; the bus was speeding from a full stop; the victims fell from the bus door when it was

opened or gave way while the bus was still running; the conductor panicked and blew his whistle after people had

already fallen off the bus; and the bus was not properly equipped with doors in accordance with law-it is clear that the

petitioners have failed to overcome the presumption of fault and negligence found in the law governing common

carriers. The petitioners' argument that the petitioners "are not insurers of their passengers" deserves no merit in

view of the failure of the petitioners to prove that the deaths of the two passengers were exclusively due to force

majeure and not to the failure of the petitioners to observe extraordinary diligence in transporting safely the

passengers to their destinations as warranted by law.

SARKIES TOURS PHILIPPINES vs. COURT OF APPEALS

Facts: On August 31, 1984, Fatima boarded petitioners De luxe bus in Manila on her way to Legaspi City. Her

brother helped her load three pieces of luggage containing all of her optometry review books, materials and

equipment, trial contact lenses, passport and visa. Her belongings were kept in the baggage compartment and during

the stopover at Daet, it was discovered that only one bag had remained in the baggage compartment. Some of the

passengers suggested retracing the route to try to recover the items, but the driver ignored them and proceeded to

Legaspi City.

Fatima reported the loss to her mother, who went to petitioners office. Petitioner merely offered her one

thousand pesos for each piece of luggage lost, which she turned down. Fatima asked the help of radio stations and

even from Philtranco bus drivers who plied the same route. Thus, one of Fatimas bags was recovered.

Respondents, through counsel, demanded satisfaction of their complaint from petitioner. Petitioner

apologized through a letter. After more than nine months of fruitless waiting, respondents decided to file the case.

The trial court ruled in favor of respondents. On appeal, the appellate court affirmed the trial courts

judgment.

Issue: Whether or not petitioner is liable for the lost baggages of Fatima.

Held: The petitioner is liable for the lost baggages. Under the Civil Code, common carriers from the nature of

their business and for reasons of public policy are bound to observe extraordinary diligence and vigilance over goods

transported by the, and this liability last from the time the goods are unconditionally placed in the possession of, and

received by the carrier for transportation until the same are delivered, actually or constructively, by the carrier to the

person who has a right to receive them, unless the loss is due to any of the excepted causes under Article 1734

thereof.

In the case at bar, the cause of the loss was petitioners negligence in not ensuring that the doors of the

baggage compartment of its bus were securely fastened. As a result of this lack of care, almost all the baggage was

lost to the prejudice of the paying passengers. Thus, petitioner is held liable.

The Court affirmed the decision of the Court of Appeals with modification.

PHILIPPINE RABBIT BUS LINES vs. IAC

Facts: Catalina Pascua with several others boarded the jeep owned by spouses Isidro Mangune and Guillerma

Carreon and driven by Tranquilino Manalo bound for Carmen, Rosales, Pangasinan.

Upon reaching Tarlac the right rear wheel of the jeepney was detached, so it was running in an unbalanced

position. Manalo stepped on the brake, as a result of which, the jeepney which was then running on the eastern lane

(its right of way) made a U-turn, invading and eventually stopping on the western lane and was hit by the petitioner

companys bus causing the death of Catalina Pascua and two other passengers.

Issue: Wether or not the Doctrine of Last Clear Chance applies in the case at bar?

Held: No, The principle about "the last clear" chance, would call for application in a suit between the owners and

drivers of the two colliding vehicles. It does not arise where a passenger demands responsibility from the carrier to

enforce its contractual obligations. For it would be inequitable to exempt the negligent driver of the jeepney and its

owners on the ground that the other driver was likewise guilty of negligence."

It is the rule under the substantial factor test that if the actor's conduct is a substantial factor in bringing about harm to

another, the fact that the actor neither foresaw nor should have foreseen the extent of the harm or the manner in

which it occurred does not prevent him from being liable. The bus driver's conduct is not a substantial factor in

bringing about harm to the passengers of the jeepney. It cannot be said that the bus was travelling at a fast speed

when the accident occurred because the speed of 80 to 90 kilometers per hour, assuming such calculation to be

correct, is yet within the speed limit allowed in highways.

The driver cannot be held jointly and severally liable with the carrier in case of breach of the contract of carriage. The

rationale behind this is readily discernible. Firstly, the contract of carriage is between the carrier and the passenger,

and in the event of contractual liability, the carrier is exclusively responsible therefore to the passenger, even if such

breach be due to the negligence of his driver. In other words, the carrier can neither shift his liability on the contract to

his driver nor share it with him, for his driver's negligence is his. Secondly, if We make the driver jointly and severally

liable with the carrier, that would make the carrier's liability personal instead of merely vicarious and consequently,

entitled to recover only the share which corresponds to the driver, contradictory to the explicit provision of Article

2181 of the New Civil Code.

JAPAN AIRLINES vs. CA

Facts: Private respondents boarded the JAL flights to Manila with a stop over at Narita Japan at the airlines'

expense. Upon arrival at Narita private respondents were billeted at Hotel Nikko Narita for the night. The next day,

private respondents went to the airport to take their flight to Manila. However, due to the Mt. Pinatubo eruption

rendered NAIA inaccessible to airline traffic. Hence, private respondents' trip to Manila was cancelled indefinitely.

JAL then booked another flight fort the passengers and again answered for the hotel accommodations but still the

succeeding flights were cancelled.

Issue: Whether or not JAL was obligated to answer for the accommodation expenses due to the force majeure.

Held: No, there is no question that when a party is unable to fulfill his obligation because of "force majeure," the

general rule is that he cannot be held liable for damages for non-performance. Corollarily, when JAL was prevented

from resuming its flight to Manila due to the effects of Mt. Pinatubo eruption, whatever losses or damages in the form

of hotel and meal expenses the stranded passengers incurred, cannot be charged to JAL. Yet it is undeniable that

JAL assumed the hotel expenses of respondents for their unexpected overnight stay on June 15, 1991.

It has been held that airline passengers must take such risks incident to the mode of travel. In this regard, adverse

weather conditions or extreme climatic changes are some of the perils involved in air travel, the consequences of

which the passenger must assume or expect.

While JAL was no longer required to defray private respondents' living expenses during their stay in Narita

on account of the fortuitous event, JAL had the duty to make the necessary arrangements to transport private

respondents on the first available connecting flight to Manila. Petitioner JAL reneged on its obligation to look after the

comfort and convenience of its passengers when it declassified private respondents from "transit passengers" to

"new passengers" as a result of which private respondents were obliged to make the necessary arrangements

themselves for the next flight to Manila.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Case Digest LaborDocument12 pagesCase Digest LaborJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsDocument3 pagesChapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsDocument3 pagesChapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsJasmin Alapag100% (2)

- Chapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsDocument3 pagesChapter VIII Ordinary Asset and Capital AssetsJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IV Gross Income NotesDocument5 pagesChapter IV Gross Income NotesJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

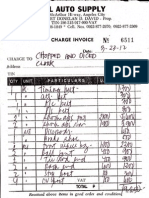

- Chopped and Diced Hot Rod Shop, Inc. Clark Freeport ZoneDocument6 pagesChopped and Diced Hot Rod Shop, Inc. Clark Freeport ZoneJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- A. What Is A "Common Carrier"?Document26 pagesA. What Is A "Common Carrier"?Jasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Tax Rates Effective January 1, 1998 Up To PresentDocument8 pagesTax Rates Effective January 1, 1998 Up To PresentJasmin AlapagNo ratings yet

- Getz 1Document1 pageGetz 1Jasmin AlapagNo ratings yet