Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press

Uploaded by

Wesley Muhammad0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views7 pagesapophis

Original Title

Apophis

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentapophis

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views7 pagesThe University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press

Uploaded by

Wesley Muhammadapophis

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 7

Apophis: On the Origin, Name, and Nature of an Ancient Egyptian AntiGod

Author(s): Ludwig D. Morenz

Source: Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 63, No. 3 (July 2004), pp. 201-205

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/424771 .

Accessed: 06/07/2014 12:13

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal

of Near Eastern Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Sun, 6 Jul 2014 12:13:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

[JNES 63 no. 3 (2004)]

2004 by The University of Chicago.

All rights reserved.

002229682004/63030003$10.00.

201

APOPHIS: ON THE ORIGIN, NAME, AND NATURE OF AN ANCIENT

EGYPTIAN ANTI-GOD*

LUDWIG D. MORENZ, University of Leipzig

Apophis is an impressive supernatural gure. This anti-god and enemy of order

surely deserves to be studied in a monograph.

1

Here, however, I offer a brief study of only

some of his attributes.

Apophis is not attested in written or pictorial sources of the Old Kingdom. Does this re-

ect the absence of the concept of Apophis, or is this an accident of transmission or in-

tended restriction caused by decorum? His rst appearance dates to the Period of Regions

(PoR),

2

where he is mentioned in the presentation of self

3

of the nomarch Ankhti of Moalla.

The dating of Ankhti has been widely discussed but can now be xed with some degree

of condence in Dynasty IX.

4

In his tomb there is a long inscription describing a great

famine,

5

a topic characteristic of the PoR.

6

In the center of this microtext embedded in the

presentation of self one reads:

tz pn n pp

this sandbank of Apophis.

* I would like to thank John Baines and Mark

Collier for their valuable suggestions and comments

on earlier drafts of this article.

1

A monograph is still lacking, but cf. E. Hornung

and A. Brodbeck, Apophis, in L, vol. 1, cols. 350

52, esp. 350; cf. also H. Brunner, Seth und Apophis,

in H. Brunner, Das hrende Herz, OBO 80 (Freiburg,

Switzerland and Gttingen, 1988), pp. 12129. One of

the most recent books dealing with Apophis is R. K.

Ritner, The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical

Practice, SAOC 54 (Chicago, 1993), index, p. 307,

sub Apophis. P. Kousoulis (University of Rhodes) is

preparing a monograph on Apophis.

2

This period was not a dark age. We should thus

replace the common term First Intermediate Period; see

the discussion in my Geschichte(n) der Zeit der Re-

gionen (Erste Zwischenzeit) im Spiegel der Gebelein-

Region, Eine fragmentarische dichte Beschreibung

(Habilitationsschrift, Tbingen, 2001), in preparation

for publication.

3

The term autobiography is rather misleading be-

cause these texts are often not auto- (in the sense of

authorship) nor are they biographies at all; see the

discussion in my Tomb Inscriptions: The Case of the

I versus Autobiography in Ancient Egypt, in Hu-

man Affairs: A Postdisciplinary Journal for Humani-

ties and Social Sciences 13 (2003): 17996.

4

E. Brovarski, The Inscribed Material of the

First Intermediate Period from Naga ed Deir (Ph.D.

diss., University of Chicago, 1989), Appendix C, The

Date of Ankhti of Moalla, pp. 101327. See also

D. Spanel, The Date of Ankhti of Moalla, in GM

78 (1984): 8794.

5

J. Vandier, Moalla, BdE 18 (Cairo, 1950), inscrip-

tion IV.10.

6

J. C. Moreno Garca, tudes sur ladministration,

le pouvoir et lidologie en gypte, de lAncien au

Moyen Empire, gyptiaca Leodiensia 4 (Lige, 1997),

pp. 192; see my Hungersnte in der Ersten Zwi-

schenzeit zwischen Topos und Realitt, in Discussions

in Egyptology 42 (1998): 8497, and my article Ver-

sorgung mit Getreide: Historische Entwicklungen und

intertextuelle Bezge zwischen ausgehendem Alten

Reich und Erster Zwischenzeit aus Achmim, in SAK

26 (1998): 81117.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Sun, 6 Jul 2014 12:13:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Near Eastern Studies 202

The name Apophis is written as: . In this inscription the snake sign serving as a

determinative has a regular form,

7

while in later writings (from the Cofn Texts onwards)

it was commonly mutilated for euphemistic reasons.

The phrase stands in a damaged part of the inscription, but it seems possible to com-

plete the sentence as proposed by J. Vandier

8

and W. Schenkel:

9

p.t jgp(.tj)

10

t m tw

[z nb hr mwt] n hkr

hr tz pn n pp

The sky is cloudy, (but) the earth is dried,

[Everyone dies] through famine

on this sandbank of Apophis (Moalla IV, 810).

Verse 1 may be a topos of the inverted world as found commonly in works of literature

such as the Admonitions or the Foretelling of Neferti that evoke the PoR, but dateat

least in written formto the Middle Kingdom.

11

Topoi of the inverted world include the

theme of natural disorder or even disaster. The alliterations p.t : jgp(.tj) and t : tw in l.c.

verse 1 can be seen as an intentional poetic feature.

12

Tz with the meaning sandbank is

also attested in other texts from the PoR that describe the shortage of water.

13

The pho-

netic writing pp is determined with the sign of a snake ( , Gardiner, Sign-list, I 14)

14

indicating Apophiss snakelike nature.

15

Unlike Seth, Apophis was never designated ntr

god. Furthermore, he was never represented in statues because he never received a cult

of his own.

Apophis is used here metaphorically. Such a usage is meaningful only if both the name

and the gure are more or less familiar. The absence of Apophis in sources dating to the

Old Kingdom, however, might be more than accidental. The gure of Apophis seems to

be originally a concept of popular religion

16

outside the decorum of the restricted sources

of the elite-culture that survived from the Old Kingdom, while statements about the nether-

world are largely lacking in the Pyramid Texts because the concept of the hereafter that

7

In the tomb of Ankhti there are no examples of

mutilated signs with the exception of the crocodile with

an arrow in its neck; see my Die SobeksSpuren von

Volksreligion im Mittleren Reich, in M. Fitzenreiter,

ed., Tierkulte im pharaonischen gypten, Internet-

Beitrge zur gyptologie und Sudanarchologie 4

(Berlin, 2003), pp. 9293.

8

J. Vandier, Moalla, pp. 223 ff., n. j.

9

W. Schenkel, Memphis, Herakleopolis, Theben,

A 12 (Wiesbaden, 1965), p. 54, n. c.

10

The determinative (sign-list N 1, typical

form of the PoR) could even be understood as an indi-

cator of the stativejgp.tj when read phonetically

as p.t.

11

E. Blumenthal, Die literarische Verarbeitung der

bergangszeit zwischen Altem und Mittlerem Reich,

in A. Loprieno, ed., Ancient Egyptian Literature: His-

tory and Forms, Probleme der gyptologie, vol. 10

(Leiden, 1996), pp. 10535, and my article Literature

as a Construction of the Past in Middle Kingdom

Egypt, in J. Tait, ed., Never Had the Like Occurred:

Egypts View of Its Past (London, 2003), pp. 10117.

12

W. Guglielmi, Der Gebrauch rhetorischer Stil-

mittel in der gyptischen Literatur, in Loprieno, ed.,

Ancient Egyptian Literature, pp. 46597, esp. 46769.

13

W. Schenkel, Die Bewsserungsrevolution im

alten gypten (Mainz, 1978), pp. 5051.

14

Note that a different snake sign was used to de-

termine ntr, god (Moalla I, 12 and I, 13).

15

There are two typical images of Apophis, as a

snake and as a turtle. The hieroglyphic sign of the

turtle (sign-list I 2) was much less common than the

various snake signs. This could be the reason why in

writing Apophis had the snake sign determinative (sign-

list I 14). The snake is, however, in accordance with

pictorial representations of Apophis, for example, in

the Amduat.

16

J. Baines, Practical Religion and Piety, in JEA

73 (1987): 7998.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Sun, 6 Jul 2014 12:13:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Apophis 203

they depict is mainly celestial. The great shifts in the PoR that included changes in reli-

gious belief and in the system of decorum might have led to Apophis being accepted by

the culture of the elite.

17

As in the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods, features appear

in the PoR that were not canonized in the Old and the Middle Kingdom. An interesting

parallel between the Predynastic Period and the PoR is provided by such fabulous animals

as the grifn, which are depicted on, for example, a Late Predynastic slate palette and in

tombs at Beni Hassan.

18

Ideas from folklore were occasionally taken over into the re-

stricted culture of the elite, and one of the periods in which such things happened more

easily is the PoR.

Apophis is mentioned more frequently in the Middle Kingdom Cofn Texts, mostly as an

enemy of either the sungod or the dead. Spell 414 describes him as a snake who attacks the

bark of Ra; his snakelike being is also indicated by the determinative (see, for example,

CT V, 244a , , ). He is evidently a snake living in the water.

19

His

mythological role is strongly marked in the underworld books of the New Kingdom. Mag-

ical spells against Apophis were numerous, and some were collected in the form of books.

20

It seems possible to interpret the name pp as a composite word, an exocentric com-

posite,

21

consisting of the two elements great and pp roar, blabber, babble. The

etymological meaning of pp would then be great babbler. Pp seems to be an onomato-

poeic word imitating the inarticulate or even nonverbal sound of this mythological water-

snake. Personal names such as Ppy are comparable in their use of the sound p. Together

with names such as Mmj, Ttj, among others, they constitute a group of Lallnamen.

22

The

doubling of the letter p intensies this quality.

23

The snake merely repeats the plosive

sound p as a kind of gibbering. Characterizing speech by onomatopoeia is very common

in Egyptian, as seen in the roots hm and zm.

24

This interpretation of Apophis as

(great) with the onomatopoeic pp is supported by Bohairic afwf or afwp giant, which

is a clear derivative of pp.

25

It might be possible to understand pp as an onomatopoeic

word for a snake, although no pp root meaning snake has been identied.

26

The syllabic

structure of the word Apophis is u pa1pu(w).

27

17

See also E. Hornung, The Triumph of Magic:

The Sun Gods Victory over Apophis, The Valley of

the Kings, trans. D. Warburton (New York, 1990),

chap. 7, esp. pp. 103 ff. (original title: Das Tal der K-

nige [Zrich and Munich, 1982]).

18

See J. Baines, Symbolic Roles of Canine Fig-

ures on Early Monuments, Archo-Nil 3 (1993): 57

74, p. 62. Fabulous animals have been quite a popular

motif in wall painting in the tombs of Middle Egypt

dating to the late PoR and the early Middle Kingdom.

19

That is why Apophis is colored in blue in some

pictures; see A. Piankoff, Les deux papyrus mythol-

ogiques de Her-Ouben au Muse du Caire, in ASAE

49 (1949): 12944, esp. p. 136 and pl. 8.

20

J. C. Goyon, Apophisbuch, in L, vol. 1, cols.

354 ff.

21

The construction is equivalent to nfr hr; cf. K.

Jansen-Winkel, Exozentrische Komposita als Rela-

tivphrasen im lteren gyptisch, in ZS 121 (1994):

5175.

22

H. G. Fischer, The Transcription of the Royal

Name Pepy, in JEA 75 (1989): esp. p. 215, n. 7.

23

Duplication creates either diminutiva or inten-

siva; see J. Osing, Die Nominalbildung des gyptischen

(Mainz, 1976), pp. 295309, sub V.B.II. Reduplikations-

bildungen (Diminutiva und Intensiva).

24

Cf. P. Derchain, propos de deux racines s-

mitiques *hm et *zm, in CdE 42 (1967): 30610. Hm

as well as zm were also duplicated: hmhm and zmz,

zmzm.

25

Contrary to the ideas of W. Vycichl, the name

should not be derived from pj; see Osing, Nominalbil-

dung, p. 345.

26

Many names of snakes are listed in the treatise

on serpents, but these do not include pp; see S. Sau-

neron, Un trait gyptien dophiologie: Papyrus du

Brooklyn Museum N

os

47.218.48 et 85, Publications

de lInstitut franais darchologie oriental, vol. 11

(Cairo, 1989).

27

E. Edel, Altgyptische Grammatik, vol. 1, AnOr

34 (Rome, 1955), s 229; Osing, Nominalbildung,

p. 297.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Sun, 6 Jul 2014 12:13:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Near Eastern Studies 204

An alternative to the above explanation would be to derive the name of the mythologi-

cal snake pp from the word p, which is attested once in the Old Kingdom, in the tomb

inscription of Ti (Urk. I, 174, 5 f.). Here p ( ) is used complementary to msqq:

[my rdy(=j) hpr] msqq.t=f nb q.t

ny rdy(=j) hpr p=f nb h ntr

[Never will I permit] that anything he hates (msqq) [should happen]eternally;

never will I permit that his p should happen before the great god.

Here too p could be an onomatopoeic word composed of the root and the plosive

sound p with the meaning stammer. On the other hand, p( p) may be just onomato-

poeic. In combination, the glottal stop and the ayin were used to characterize foreign,

barbaric languages by onomatopoeia in the root ( j).

28

The deceased should not stam-

mer but should speak clearly and articulately before the great god in the hereafter. Accord-

ing to this interpretation pp seems to be a construct on the intensive pattern ABC/C

29

with the meaning the one who stammers most. Here one may compare the sea monster

tannin in the Hebrew Bible. This term is also found in the sense of serpent. The etymol-

ogy of tannin is uncertain, but it has been suggested that it is related to the root TNH (re-

count, rehearse) as lament, howl.

30

The noblest function of language is communication.

31

Meaning and relationships are

founded by it, and the entire web of culture depends on communication. Apophis, how-

ever, is strictly anticommunicative. In the underworld books, Apophis appears as the g-

ure of darkness and embodiment of anticommunication. Language endows meaning and

relation, and Apophis is the negation of precisely these ideas. In the seventh hour of the

Amduat about Apophis it is said:

jn hrw=f ssm ntr.w r=f

It is his (Apophiss) voice that leads the gods to him

32

and in the sixth hour of the Book of the Gates:

33

jw.tj jr.tj {n}[=fj]hf.w pn

jw.tj fnq=f jw.tj msqr.wj=fj

zrk=f m hmhm.t=f

nh=f m qwj=f qs=f

One without its eyes is this snake,

without its nose and without its ears:

it breathes its screaming (hmhm.t),

it lives on its own shouting.

28

Cf. L. D. Bell, Interpreters and Egyptianized

Nubians in Ancient Egyptian Foreign Policy: Aspects

of the History of Egypt and Nubia (Ph.D. diss., Uni-

versity of Pennsylvania, 1976).

29

Edel, Altgyptische Grammatik, s 229, p. 100,

and Osing, Nominalbildung, p. 297.

30

K. van der Toorn, B. Becking, and P. van der

Horst, eds., Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the

Hebrew Bible, 2d ed. (Leiden, 1999), p. 1579, sub

Tannin.

31

For the importance of communication in Egyp-

tian civilization, see J. Assmann, Maat: Gerechtig-

keit und Unsterblichkeit im Alten gypten (Munich,

1990).

32

E. Hornung, ed., Texte zum Amduat, Teil II: Lang-

fassung, 4. bis 8. Stunde, gyptiaca Helvetica 14 (Ge-

neva, 1992), p. 551.

33

Idem, Das Buch von den Pforten des Jenseits,

gyptiaca Helvetica 7 (Geneva, 1979) (Text), scene

35, pp. 21314.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Sun, 6 Jul 2014 12:13:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Apophis 205

This short stanza describes Apophis as an antisocial creature without any proper sensory

organs. Apophis is just noisy. In the litany of negative epithets (the names of Apophis which

shall not be, n rn n pp ntj nn wn=sn, in P. Bremner-Rhind 32,1332,42), Apophis is

called:

pp h hmhm.tj

Apophis, the fallen one, the Roarer (32,17).

A supercially similar but in reality very different phenomenon from Apophis is the lan-

guage of Yahweh as described especially in Deut. 4:12 and 5:22. The people of Israel did

not hear distinct words but only the voice (5:22) or the voice of words (4:12). That

is why Moses acted as translator of the language of God, which was incomprehensible to

ordinary people.

34

The language of the gods was transhuman in Egypt as well. It was the

mysterious language of the baboons.

35

A physician of the late Old Kingdom held the

title j hmw.t st.t speaker of the secret art, which refers to a perhaps magical language

( j) in medicine (hmw.t st.t).

36

In this context j means metaphorically either an abra-

cadabra or possibly a genuine foreign language. In order to be efcacious, this language

had to transcend daily life, and so had to be in some sense non-Egyptian.

In summary, Apophis is conceived as a great babbler, a snakelike being living in the

water. One should recall the general context of Egypt in the ancient Near East (cf. Levia-

than, Tannin, etc.), where the image of a snake-dragon that symbolizes water as well as re

was very common.

37

Most probably the conception of Apophis was transferred from

popular religion into the culture of the elite during the PoR and remained signicant until

the very end of ancient Egyptian culture or even later. Perhaps Apophis lived on, only

slightly changed, as the dragon of the Middle Ages.

38

Holding back water is one of the

most characteristic activities of dragons, and this notion is present in the very oldest

known occurrence of Apophis, namely, in the metaphorical expression sandbank of Apo-

phis attested in the tomb of Ankhti at Moalla.

34

To translate the language of Yahweh was seen as

one of the most important prophetic tasks of Moses;

cf. Philo Vita Mosis 2. 18991.

35

H. te Velde, Some Remarks on the Mysterious

Language of the Baboons, in J. H. Kamstra, H. Milde,

and K. Wagtendonk, eds., Funerary Symbols and Re-

ligion (Festschrift M. S. H. G. Heerma van Voss)

(Kampen, 1988), pp. 12937.

36

See my article (Magische) Sprache der gehei-

men Kunst, in SAK 24 (1997): 191201.

37

O. Keel, Die Welt der altorientalischen Bilder-

symbolik und das Alte Testament (Zrich, 1972), pp.

3947.

38

E. Brunner-Traut, AltgyptenUrsprungsland des

mittelalterlich-europischen Drachen? in E. Brunner-

Traut, Gelebte Mythen: Beitrge zum altgyptischen

Mythos (Darmstadt, 1988), pp. 10916.

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Sun, 6 Jul 2014 12:13:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

This content downloaded from 67.115.155.19 on Sun, 6 Jul 2014 12:13:08 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Hyperserotonemia in Autism: The Potential Role of 5HT-related Gene VariantsDocument6 pagesHyperserotonemia in Autism: The Potential Role of 5HT-related Gene VariantsWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Adams 1Document5 pagesAdams 1Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Bpa 1Document9 pagesBpa 1Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- William HerrmannDocument68 pagesWilliam HerrmannWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Drugs 7Document6 pagesDrugs 7Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Amygdala: Eyes Wide Open: Current Biology Vol 24 No 20 R1000Document3 pagesAmygdala: Eyes Wide Open: Current Biology Vol 24 No 20 R1000Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Blond, Tall, With Honey-Colored Eyes Jewish Ownership of Slaves in The Ottoman EmpireDocument19 pagesBlond, Tall, With Honey-Colored Eyes Jewish Ownership of Slaves in The Ottoman EmpireBlack SunNo ratings yet

- Buddha GodDocument3 pagesBuddha GodWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Dying God 2Document12 pagesDying God 2Wesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- South African Archaeological SocietyDocument15 pagesSouth African Archaeological SocietyWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Native Americans AfricoidDocument24 pagesNative Americans AfricoidWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Africanity of SpainDocument9 pagesAfricanity of SpainWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Theology of ATRDocument108 pagesTheology of ATRWesley Muhammad100% (1)

- Adam and Eve Were IraniansDocument3 pagesAdam and Eve Were IraniansWesley MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Theology of MemphisDocument6 pagesTheology of MemphisWesley Muhammad100% (2)

- False Goddess 2Document12 pagesFalse Goddess 2Wesley Muhammad100% (1)

- Chapter 2: Safe Lab Procedures and Tool Use: IT Essentials: PC Hardware and Software v4.1Document11 pagesChapter 2: Safe Lab Procedures and Tool Use: IT Essentials: PC Hardware and Software v4.1Uditha MuthumalaNo ratings yet

- Commonly Asked Short QuestionsDocument4 pagesCommonly Asked Short QuestionsShubham JainNo ratings yet

- Iphone DissertationDocument7 pagesIphone DissertationPapersWritingServiceCanada100% (1)

- 322 Dynamic Demographic Characteristic Slum Population in Nashik City With Special Reference From 2011Document6 pages322 Dynamic Demographic Characteristic Slum Population in Nashik City With Special Reference From 2011B-15 Keyur BhanushaliNo ratings yet

- A Note On Ethics and StrategyDocument3 pagesA Note On Ethics and StrategyLaura RamonaNo ratings yet

- LSP 401 Ip S1 12-13Document4 pagesLSP 401 Ip S1 12-13Mary TeohNo ratings yet

- Take Home Quizes Al-JaberDocument21 pagesTake Home Quizes Al-JaberalfredomedardoNo ratings yet

- AUD689 Tutorial Question Legal LiabilityDocument5 pagesAUD689 Tutorial Question Legal LiabilityJebatNo ratings yet

- Christopher MontoyaDocument1 pageChristopher MontoyaUF Student GovernmentNo ratings yet

- 03 - Rise of The Allies 1Document41 pages03 - Rise of The Allies 1evanpate0No ratings yet

- Drug Chart 7 - Hee InternetDocument19 pagesDrug Chart 7 - Hee InternetAhmzzdNo ratings yet

- Powermax45 Despiece AntorchaDocument5 pagesPowermax45 Despiece AntorchaWall OmarNo ratings yet

- CS701 - Theory of Computation Assignment No.1: InstructionsDocument2 pagesCS701 - Theory of Computation Assignment No.1: InstructionsIhsanullah KhanNo ratings yet

- Expt. 8 Salivary DigestionDocument25 pagesExpt. 8 Salivary DigestionLESLIE JANE BALUYOS JALANo ratings yet

- May Chronology JuneDocument80 pagesMay Chronology Junesahil popliNo ratings yet

- The Brain and Nervous System (Psychology) Unit 14: An Academic ReportDocument7 pagesThe Brain and Nervous System (Psychology) Unit 14: An Academic ReportOlatokunbo SinaayomiNo ratings yet

- Talent Acquisition 2008 - Survey and Analysis of The Changing Recruiting Landscape PDFDocument20 pagesTalent Acquisition 2008 - Survey and Analysis of The Changing Recruiting Landscape PDFVaishnavi SivaNo ratings yet

- Circular Motion: American Journal of Physics July 2000Document8 pagesCircular Motion: American Journal of Physics July 2000GurjotNo ratings yet

- Nigeria's Agenda 21 Draft Objectives and Strategies ForDocument77 pagesNigeria's Agenda 21 Draft Objectives and Strategies ForbenNo ratings yet

- Dwadasa Nama of KartaveeryaDocument4 pagesDwadasa Nama of KartaveeryaVijaya BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Arduino UNO Rev3e SCH PDFDocument1 pageArduino UNO Rev3e SCH PDFHery Febrian DinogrohoNo ratings yet

- Opsrey - Acre 1291Document97 pagesOpsrey - Acre 1291Hieronymus Sousa PintoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Econometrics Ii (Econ-3062) : Mohammed Adem (PHD)Document83 pagesIntroduction To Econometrics Ii (Econ-3062) : Mohammed Adem (PHD)ፍቅር እስከ መቃብር100% (2)

- Srilanka UpdatedDocument6 pagesSrilanka UpdatedBaba HeadquaterNo ratings yet

- Yashoda Singh Indian Coins Lots 1001-1242Document29 pagesYashoda Singh Indian Coins Lots 1001-1242Ashwin SevariaNo ratings yet

- Asterisk For Dumb MeDocument164 pagesAsterisk For Dumb MeAndy CockroftNo ratings yet

- Topic On CC11Document3 pagesTopic On CC11Free HitNo ratings yet

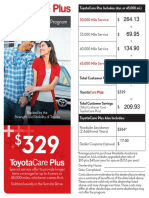

- ToyotaCare Plus CalculationDocument2 pagesToyotaCare Plus CalculationShao MaNo ratings yet

- Category:UR Madam / Sir,: Please Affix Your Recent Passport Size Colour Photograph & Sign AcrossDocument2 pagesCategory:UR Madam / Sir,: Please Affix Your Recent Passport Size Colour Photograph & Sign AcrossVasu Ram JayanthNo ratings yet

- SAP BODS Course Content at NBITSDocument3 pagesSAP BODS Course Content at NBITSPranay BalagaNo ratings yet