Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Us Colonialism

Us Colonialism

Uploaded by

Bambie Joy InovejasCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Layered Cross PlansDocument14 pagesLayered Cross PlansRJ BevyNo ratings yet

- Periods of Philippine LiteratureDocument8 pagesPeriods of Philippine Literatureipan.rhechelannmNo ratings yet

- Pre-Colonial (Early Times - 1564)Document11 pagesPre-Colonial (Early Times - 1564)Myra Agpawa-EspantoNo ratings yet

- Pre-Colonial PeriodDocument19 pagesPre-Colonial Periodmary ann liwagNo ratings yet

- 21st Century LiteratureDocument8 pages21st Century LiteratureJanaNo ratings yet

- Transcript of Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesTranscript of Philippine LiteratureKimberly Abanto JacobNo ratings yet

- Periods of Philippine LiteratureDocument8 pagesPeriods of Philippine LiteratureJohn Terrence M. RomeroNo ratings yet

- Precolonial PeriodDocument2 pagesPrecolonial PeriodMartin Ceazar HermocillaNo ratings yet

- Pre Colonial 21stDocument35 pagesPre Colonial 21stbusinechelsea7No ratings yet

- Notes 1Document4 pagesNotes 1Adrian Steven QuevadaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature Module 1Document5 pagesPhilippine Literature Module 1Rovin Jae EsguerraNo ratings yet

- History of Philippine LiteratureDocument14 pagesHistory of Philippine Literaturedanica dimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature Course Module Content Gen EdDocument56 pagesPhilippine Literature Course Module Content Gen EdRadzmiya SulaymanNo ratings yet

- History of Philippine LiteratureDocument34 pagesHistory of Philippine LiteratureZack FairNo ratings yet

- Phil. Literature Santos, S.Document3 pagesPhil. Literature Santos, S.shara santosNo ratings yet

- Phil Lit QuizDocument1 pagePhil Lit QuizAj MagnoNo ratings yet

- DocxDocument2 pagesDocxAikawa AyumoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document5 pagesLesson 2alierose616No ratings yet

- SoftDocument40 pagesSoftjohn kenneth bayangosNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature Course Module Content - Gen EdDocument53 pagesPhilippine Literature Course Module Content - Gen EdKathy R. PepitoNo ratings yet

- Merged Curriculum Devp. LessonDocument5 pagesMerged Curriculum Devp. Lessonruru6No ratings yet

- Unit Ii: Historical Development of Philippine Literature at The End of This Unit Topic, You Will Be Able ToDocument4 pagesUnit Ii: Historical Development of Philippine Literature at The End of This Unit Topic, You Will Be Able ToMeynard CastroNo ratings yet

- N 1 Introduction To Literatures and Literary Types Eng 8Document7 pagesN 1 Introduction To Literatures and Literary Types Eng 8menezachristalNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature History Timeline: - Historical EventsDocument11 pagesPhilippine Literature History Timeline: - Historical EventsJessa Jumao AsNo ratings yet

- Reports - Historical Overview of Philippine LiteratureDocument13 pagesReports - Historical Overview of Philippine LiteratureMa. Cristina UyNo ratings yet

- Pre Colonial To Revolutionary EN7Document5 pagesPre Colonial To Revolutionary EN7mamu chabeNo ratings yet

- 21st Century LiteratureDocument4 pages21st Century LiteratureMichael JustinNo ratings yet

- FinalModule.21st Century LiteratureDocument24 pagesFinalModule.21st Century Literaturetampocashley15No ratings yet

- The Philippine LiteratureDocument21 pagesThe Philippine LiteratureDennis De JesusNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Document11 pagesPhilippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Estelito MedinaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsDocument11 pagesPhilippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsRedenRosuenaGabrielNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Document11 pagesPhilippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217God Warz Dungeon GuildNo ratings yet

- Historical and Literary Highlights: Darangen (Maranao) Hudhud (Ifugao) and Ulahingan (Manobo) - These Epics RevolveDocument5 pagesHistorical and Literary Highlights: Darangen (Maranao) Hudhud (Ifugao) and Ulahingan (Manobo) - These Epics RevolveJan Kenrick SagumNo ratings yet

- 3 Literary Forms PHDocument11 pages3 Literary Forms PHSean C.A.ENo ratings yet

- 7-Phil Literature - Written ReportDocument7 pages7-Phil Literature - Written ReportDana Dela ReaNo ratings yet

- Hlan Module 2 - Techniques in Reading Poetry and DramasDocument19 pagesHlan Module 2 - Techniques in Reading Poetry and DramasJohn Mark ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Senior High School Department: Quarter 3 Module - 2 SEM - SY: 2021-2022Document12 pagesSenior High School Department: Quarter 3 Module - 2 SEM - SY: 2021-2022Jedidiah Daniel Lopez HerbillaNo ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument15 pagesPhilippine LiteratureBilly ChubbsNo ratings yet

- Artsandliterature 150811010716 Lva1 App6891Document22 pagesArtsandliterature 150811010716 Lva1 App6891Clarisle NacanaNo ratings yet

- Oral Lore (Ho 3)Document2 pagesOral Lore (Ho 3)Donali Gem Manalang PableoNo ratings yet

- Cel 347100392Document31 pagesCel 347100392cel resuentoNo ratings yet

- Historical Timeline of Philippine LiteratureDocument8 pagesHistorical Timeline of Philippine Literaturerossana rondaNo ratings yet

- The Filipino Poem Week 1Document56 pagesThe Filipino Poem Week 1Monica MarticioNo ratings yet

- Untitled Document (3) SsDocument3 pagesUntitled Document (3) Sssogixas263No ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument5 pagesPhilippine LiteratureMelrene Isabel MoralesNo ratings yet

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureHamaNo ratings yet

- Pre Spanish Period Phil LitDocument2 pagesPre Spanish Period Phil Litfraphyjane17No ratings yet

- 21st Assignment 1Document12 pages21st Assignment 1Lovely PitiquenNo ratings yet

- 21st Century ReviewerDocument15 pages21st Century ReviewerKimberly DalagNo ratings yet

- Literary History of Phil Lit (Pre Colonial-Japanese)Document1 pageLiterary History of Phil Lit (Pre Colonial-Japanese)Manuel J. RadislaoNo ratings yet

- Forms of Philipine LiteratureDocument7 pagesForms of Philipine LiteratureJohn Lee Damondon GilpoNo ratings yet

- The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature: Christine F. Godinez-OrtegaDocument7 pagesThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literature: Christine F. Godinez-OrtegaCassy DollagueNo ratings yet

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literaturenica-chan0% (2)

- Literary Forms in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesLiterary Forms in The PhilippinesKmerylENo ratings yet

- Oral Lore From Pre-Colonial Times ( - 1564) : Mr. Harry Dave B. VillasorDocument22 pagesOral Lore From Pre-Colonial Times ( - 1564) : Mr. Harry Dave B. VillasorJohn Carl AparicioNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Lit Topic For MID-TERMDocument54 pages21st Century Lit Topic For MID-TERMAvegail Constantino0% (1)

- Philippine LiteratureDocument10 pagesPhilippine LiteratureEecya LacisabNo ratings yet

- Periods of Philippine Literature Periods of Philippine LiteratureDocument25 pagesPeriods of Philippine Literature Periods of Philippine Literaturedanica bianca dulayNo ratings yet

- Periods of PH Literature: (Pre-Colonial Period Until The Contemporary Period)Document33 pagesPeriods of PH Literature: (Pre-Colonial Period Until The Contemporary Period)Thalia SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Literature in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesLiterature in The PhilippineskaskaraitNo ratings yet

- Folk-Tales of Angola - Fifty Tales, with Ki-Mbundu Text Literal English Translation Introduction, and NotesFrom EverandFolk-Tales of Angola - Fifty Tales, with Ki-Mbundu Text Literal English Translation Introduction, and NotesNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Self Compassion Exercise PDFDocument3 pagesReflections On Self Compassion Exercise PDFNash PanimbangNo ratings yet

- PRESENT CONTINUOS - Ildefonso - Solis LuisDocument6 pagesPRESENT CONTINUOS - Ildefonso - Solis LuisRaul Osorio DiazNo ratings yet

- Blood PornDocument15 pagesBlood PornSean FinneyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Vlsi Circuits and Systems With CDDocument33 pagesIntroduction To Vlsi Circuits and Systems With CDVishu VishwajaNo ratings yet

- Flirting With Humanity PDFDocument11 pagesFlirting With Humanity PDFValerie WalkerNo ratings yet

- The Subjunctives Bahasa InggrisDocument7 pagesThe Subjunctives Bahasa InggrisMudhoffar SyarifNo ratings yet

- 3 Doors Down - It's Not My Time - Marcada 2Document2 pages3 Doors Down - It's Not My Time - Marcada 2giandeoliveiraNo ratings yet

- Classifications of ArtDocument2 pagesClassifications of ArtAnnaj GabardaNo ratings yet

- Question Paper - PhysicsDocument2 pagesQuestion Paper - Physicsjeru2003No ratings yet

- Indice de HimnosDocument112 pagesIndice de HimnosDulcesMelodíasNo ratings yet

- Absolute Beginner French For Every Day S1 #1 Top 25 French PhrasesDocument5 pagesAbsolute Beginner French For Every Day S1 #1 Top 25 French PhrasesMaurinanfNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Exam1Document2 pagesVocabulary Exam1modernstellarNo ratings yet

- (Quranic/ Classical Written Forms) (Variant With Vowels/ Without Vowels) (Various Spellings)Document19 pages(Quranic/ Classical Written Forms) (Variant With Vowels/ Without Vowels) (Various Spellings)maazaNo ratings yet

- Grammar Review: A B C D e FDocument2 pagesGrammar Review: A B C D e FMireya Menchaca CruzNo ratings yet

- Learn Greek (6 of 7) - The Nominal System, Part IDocument34 pagesLearn Greek (6 of 7) - The Nominal System, Part IBot Psalmerna100% (2)

- Making A Simple and Easy Charcoal Coal ForgeDocument9 pagesMaking A Simple and Easy Charcoal Coal Forgemarius_danila8736No ratings yet

- No-Bling DOTA Mod ReadmeDocument347 pagesNo-Bling DOTA Mod Readmedg dNo ratings yet

- Bruce Lee's Top 10 Rules For SuccessDocument2 pagesBruce Lee's Top 10 Rules For SuccessRamon ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Celebrity CruisesDocument2 pagesCelebrity CruisesDudu LauraNo ratings yet

- Williamson ScriptDocument4 pagesWilliamson ScriptDerek Johnson Jr.No ratings yet

- B-Line CTME-13Document284 pagesB-Line CTME-13Leizer LipaNo ratings yet

- Embelishment Italian TabulationsDocument36 pagesEmbelishment Italian TabulationsMarcelo Cazarotto BrombillaNo ratings yet

- The Nature of The Dream in The Great Gatsby.Document129 pagesThe Nature of The Dream in The Great Gatsby.Dinakaran PDNo ratings yet

- Ernest Renan The Song of Songs PDFDocument180 pagesErnest Renan The Song of Songs PDFanonimo anonimoNo ratings yet

- Internal Diagnostics 605Document10 pagesInternal Diagnostics 605Iliyan HristovNo ratings yet

- Gr6 Syllabus 2019Document11 pagesGr6 Syllabus 2019nirmala somanNo ratings yet

- Manuale Moon IndesitDocument36 pagesManuale Moon IndesitgsaviNo ratings yet

- Narrative ReportDocument1 pageNarrative ReportArvin EleuterioNo ratings yet

- Symmetric Patterns: The Nature of Mathematics and Mathematics in NatureDocument23 pagesSymmetric Patterns: The Nature of Mathematics and Mathematics in NaturejennaNo ratings yet

Us Colonialism

Us Colonialism

Uploaded by

Bambie Joy InovejasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Us Colonialism

Us Colonialism

Uploaded by

Bambie Joy InovejasCopyright:

Available Formats

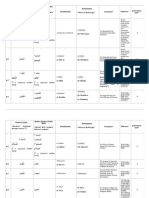

Literary Period

Pre-Colonial

Introduction

philippine literature

Early Times - to

1564

Filipinos often lose sight of the fact that the first period of the Philippine literary

history is the longest. Certain events from the nation's history had forced lowland

Filipinos to begin counting the years of history from 1521, the first time written records

by Westerners referred to the archipelago later to be called "Las islas Filipinas".

However, the discovery of the "Tabon Man" in a cave in Palawan in 1962, has allowed us

to stretch our prehistory as far as 50,000 years back. The stages of that prehistory show

how the early Filipinos grew in control over their environment. Through the researches

and writings about Philippine history, much can be reliably inferred about precolonial

Philippine literature from an analysis of collected oral lore of Filipinos whose ancestors

were able to preserve their indigenous culture by living beyond the reach of Spanish

colonial administrators.

The oral literature of the precolonial Filipinos bore the marks of the community. The

subject was invariably the common experience of the people constituting the villagefood-gathering, creature and objects of nature, work in the home, field, forest or sea,

caring for children, etc. This is evident in the most common forms of oral literature like

the riddle, the proverbs and the song, which always seem to assume that the audience

is familiar with the situations, activities and objects mentioned in the course of

expressing a thought or emotion. The language of oral literature, unless the piece was

part of the cultural heritage of the community like the epic, was the language of daily

life. At this phase of literary development, any member of the community was a potential

poet, singer or storyteller as long as he knew the language and had been attentive to the

conventions f the forms.

In settlements along or near the seacoast, a native syllabary was in use before the

Spaniards brought over the Roman alphabet. The syllabary had three vowels (a, i-e, u-o)

and 14 consonants (b, d, g, h, k, l, m, n, ng, p, r, s, t, w, and y) but, curiously enough, had

no way of indicating the consonantal ending words. This lends credence to the belief

that the syllabary could not have been used to produce original creative works which

would all but be undecipherable when read by one who had had no previous contact

with the text. When the syllabary fell into disuse among the Christianized Filipinos,

much valuable information about precolonial culture that could had been handed down

to us was lost. Fewer and fewer Filipinos kept records of their oral lore, and fewer and

fewer could decipher what had been recorded in earlier times. The perishable materials

on which the Filipinos wrote were disintegrate and the missionaries who believed that

indigenous pagan culture was the handicraft of the devil himself destroyed those that

remained.

There are two ways by which the uniqueness of indigenous culture survived

colonization. First, by resistance to colonial rule. This was how the Maranaws, the

Maguindanaws, and the Tausogs of Mindanao and Igorots, Ifugao, Bontocs and Kalingas

of the Mountain Province were able to preserve the integrity of their ethnic heritage. The

Tagbanwas, Tagabilis, Mangyans, Bagobos, Manuvus, Bilaan, Bukidnons, and Isneg

could cling on the traditional way of life because of the inaccessibility of settlements. It

is to these descendants of ancient Filipinos who did not come under the cultural sway

of Western colonizers that we turn when we look for examples of oral lore. Oral lore they

have been preserve like epics, tales, songs, riddles, and proverbs that are now windows

to a past with no written records which can be studied.

Ancient Filipinos possessed great wealth of lyric poetry. There were many songs of

great variety in lyrics and music as well as meter. Each mountain tribe and each group

of lowland Filipinos had its own. Most of the may be called folksongs in that there can

be traced in them various aspects of the life and customs of the people.

Precolonial poetry were composed of poems composed of different dialects of the

islands. The first Spanish settlers themselves found such poetry, reproduced them, and

recorded in their reports and letters to Spain. Although precolonial poems are distinct

from the lyrics of the folksongs the said poems were usually chanted when recited, as is

still the custom of all Asiatic peoples and Pacific Ocean tribes. It is true that many of the

precolonial poetry is crude in ideology and phraseology as we look at it with our present

advanced knowledge of what poetry should be. Considering the fact that early Filipinos

never studied literature and never had a chance to study poetry and poetic technique, it

Introduction to philippine literature

Literary Period

After EDSA

1986 - Present

The year 1986 marks a new beginning of a new scene for Filipino writers and artists. It saw

the downfall of late President Ferdinand Marcos when he placed the Philippines under martial

rule last September 21,1972. This action does not only oppress the writers' right to free

expression but also created conditions that made collaboration and cooperation convenient

choices for artists' struggling for recognition and survival. Furthermore, the growth of

underground writing was created both in urban and in the countryside.

The popular "Edsa Revolution" (EDSA, a highway in Metro Manila that runs north to south

from Caloocan to Baclaran) has paved the way for the flight of the dictator and his family to

Hawaii, USA on February 24,1986. The revolt established the presidency of Corazon Aquino,

which marked the "restoration" of a pre-Martial Law society. However, the Philippines did not

recover that easily. The years that followed "Edsa" was a wild "roller-coaster" ride for many

Filipinos. The unease times was caused by natural disasters that left the economic plans in

shambles.

Militancy and belligerence best describes writing under the Martial Law regime. With the

overthrow of the enemy in 1986, however, the literary activity showed certain disorientation

manifesting itself in a proliferation of concerns taken up by individual writers and groups.

Creative writing centers after Edsa maybe grouped into two. Academic institutions where

Creative Writing is part of the curricular offerings, and students majoring in Literature are able to

come in contact with elder creative writers/critics/professors belonged to the first group. Such

academic institutions includes the Silliman University; the University of the Philippines; the

Ateneo de Manila University; De la Salle University; and last but not the least, San Carlos

University in Cebu.

Introduction to philippine literature

The second group is composed of writers' organizations that periodically sponsor symposia

on writing and/or set up workshops for its members and other interested parties. UMPIL (Unyon

ng mga Manunulat ng Pilipino), PANULAT (Pambansang Unyon ng mga Manunulat), Panday-Lipi,

GAT (Galian sa Arte at Tula), KATHA, LIRA (Linangan sa Imahen, Retorika at Anyo), GUMIL

(Gunglo Dagiti Mannurat nga Ilokano), LUDABI (Lubas sa Dagang Binisaya) and P.E.N.

Writers get to hear about new developments in writing and derive enthusiasm for their craft

through these twin centers. The two "unyon" function as umbrellas under which writers

belonging to a diversity of organizations socialize with fellow writers.

Award giving bodies, annual competitions and publications provide the incentives for writers

to keep producing. These actions perform the important service of keeping the writers in the

public consciousness, making it possible for commentators and audiences to identify significant

established writers and give attention to emerging new talents.

The National Commission on Culture and the Arts (NCCA), a post-EDSA state sponsored

institution, was created by the law in 1992, superseding the Presidential Commission on Culture

and the Arts which was established in 1987. The said institution has a Committee on Literary Arts

which funds workshops, conferences, publications and a variety of projects geared towards the

production of a "national literature". The committee has the aim of developing writing that is

multi-lingual, multi-cultural, and truly national.

Non-governmental organizations have helped hand in hand with some institutions in giving

recognition to writers from specific sectors in the society. These NGO's includes the Amado V.

Hernandez Foundation; the GAPAS foundation, and the KAIBIGAN.

Campus publications are another group of outlet that is of importance as a source of nontraditional, experimental writing. These campus publications could either be a weekly student

newspapers, quarterly magazines, or annual literary journals. The University of the Philippines

has the Collegian; The Diliman Review; and The Literary Apprentice. Silliman University has

Sands and Coral; Ateneo de Manila University issues Heights and Philippine Studies; De la Salle

University has Malate, Likha, and Malay to offer; University of Santo Tomas publishes The

Varsitarian.

Overall, the character of the Philippine literary scene after "EDSA" maybe pinpointed be

referring to the theories that inform literary production, to the products issuing from the

publishers, to the dominant concerns demonstrated by the writers' output, and to the direction

towards which literary studies are tending.

1. There is in the academe an emerging critical orientation that draws its concerns and

insights from literary theorizing current in England and the United States.

2. Post-EDSA publishing has been marked by adventurousness, a willingness to gamble on

"non-traditional" projects.

3. The declining prestige of the New Criticism, whose rigorous aesthetic norms has

previously functioned as a Procrustean bed on which Filipino authors and their works were

measured, has opened a gap in the critical evaluation of literary works.

4. The fourth and final characteristic of post-EDSA writing is the development thrust towards

the retrieval and the recuperation of writing in Philippine languages other than Tagalog.

Introduction to philippine literature

You might also like

- Layered Cross PlansDocument14 pagesLayered Cross PlansRJ BevyNo ratings yet

- Periods of Philippine LiteratureDocument8 pagesPeriods of Philippine Literatureipan.rhechelannmNo ratings yet

- Pre-Colonial (Early Times - 1564)Document11 pagesPre-Colonial (Early Times - 1564)Myra Agpawa-EspantoNo ratings yet

- Pre-Colonial PeriodDocument19 pagesPre-Colonial Periodmary ann liwagNo ratings yet

- 21st Century LiteratureDocument8 pages21st Century LiteratureJanaNo ratings yet

- Transcript of Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesTranscript of Philippine LiteratureKimberly Abanto JacobNo ratings yet

- Periods of Philippine LiteratureDocument8 pagesPeriods of Philippine LiteratureJohn Terrence M. RomeroNo ratings yet

- Precolonial PeriodDocument2 pagesPrecolonial PeriodMartin Ceazar HermocillaNo ratings yet

- Pre Colonial 21stDocument35 pagesPre Colonial 21stbusinechelsea7No ratings yet

- Notes 1Document4 pagesNotes 1Adrian Steven QuevadaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature Module 1Document5 pagesPhilippine Literature Module 1Rovin Jae EsguerraNo ratings yet

- History of Philippine LiteratureDocument14 pagesHistory of Philippine Literaturedanica dimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature Course Module Content Gen EdDocument56 pagesPhilippine Literature Course Module Content Gen EdRadzmiya SulaymanNo ratings yet

- History of Philippine LiteratureDocument34 pagesHistory of Philippine LiteratureZack FairNo ratings yet

- Phil. Literature Santos, S.Document3 pagesPhil. Literature Santos, S.shara santosNo ratings yet

- Phil Lit QuizDocument1 pagePhil Lit QuizAj MagnoNo ratings yet

- DocxDocument2 pagesDocxAikawa AyumoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document5 pagesLesson 2alierose616No ratings yet

- SoftDocument40 pagesSoftjohn kenneth bayangosNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature Course Module Content - Gen EdDocument53 pagesPhilippine Literature Course Module Content - Gen EdKathy R. PepitoNo ratings yet

- Merged Curriculum Devp. LessonDocument5 pagesMerged Curriculum Devp. Lessonruru6No ratings yet

- Unit Ii: Historical Development of Philippine Literature at The End of This Unit Topic, You Will Be Able ToDocument4 pagesUnit Ii: Historical Development of Philippine Literature at The End of This Unit Topic, You Will Be Able ToMeynard CastroNo ratings yet

- N 1 Introduction To Literatures and Literary Types Eng 8Document7 pagesN 1 Introduction To Literatures and Literary Types Eng 8menezachristalNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature History Timeline: - Historical EventsDocument11 pagesPhilippine Literature History Timeline: - Historical EventsJessa Jumao AsNo ratings yet

- Reports - Historical Overview of Philippine LiteratureDocument13 pagesReports - Historical Overview of Philippine LiteratureMa. Cristina UyNo ratings yet

- Pre Colonial To Revolutionary EN7Document5 pagesPre Colonial To Revolutionary EN7mamu chabeNo ratings yet

- 21st Century LiteratureDocument4 pages21st Century LiteratureMichael JustinNo ratings yet

- FinalModule.21st Century LiteratureDocument24 pagesFinalModule.21st Century Literaturetampocashley15No ratings yet

- The Philippine LiteratureDocument21 pagesThe Philippine LiteratureDennis De JesusNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Document11 pagesPhilippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Estelito MedinaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsDocument11 pagesPhilippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsRedenRosuenaGabrielNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217Document11 pagesPhilippine Literature: Marawoy, Lipa City, Batangas 4217God Warz Dungeon GuildNo ratings yet

- Historical and Literary Highlights: Darangen (Maranao) Hudhud (Ifugao) and Ulahingan (Manobo) - These Epics RevolveDocument5 pagesHistorical and Literary Highlights: Darangen (Maranao) Hudhud (Ifugao) and Ulahingan (Manobo) - These Epics RevolveJan Kenrick SagumNo ratings yet

- 3 Literary Forms PHDocument11 pages3 Literary Forms PHSean C.A.ENo ratings yet

- 7-Phil Literature - Written ReportDocument7 pages7-Phil Literature - Written ReportDana Dela ReaNo ratings yet

- Hlan Module 2 - Techniques in Reading Poetry and DramasDocument19 pagesHlan Module 2 - Techniques in Reading Poetry and DramasJohn Mark ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Senior High School Department: Quarter 3 Module - 2 SEM - SY: 2021-2022Document12 pagesSenior High School Department: Quarter 3 Module - 2 SEM - SY: 2021-2022Jedidiah Daniel Lopez HerbillaNo ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument15 pagesPhilippine LiteratureBilly ChubbsNo ratings yet

- Artsandliterature 150811010716 Lva1 App6891Document22 pagesArtsandliterature 150811010716 Lva1 App6891Clarisle NacanaNo ratings yet

- Oral Lore (Ho 3)Document2 pagesOral Lore (Ho 3)Donali Gem Manalang PableoNo ratings yet

- Cel 347100392Document31 pagesCel 347100392cel resuentoNo ratings yet

- Historical Timeline of Philippine LiteratureDocument8 pagesHistorical Timeline of Philippine Literaturerossana rondaNo ratings yet

- The Filipino Poem Week 1Document56 pagesThe Filipino Poem Week 1Monica MarticioNo ratings yet

- Untitled Document (3) SsDocument3 pagesUntitled Document (3) Sssogixas263No ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument5 pagesPhilippine LiteratureMelrene Isabel MoralesNo ratings yet

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesThe Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureHamaNo ratings yet

- Pre Spanish Period Phil LitDocument2 pagesPre Spanish Period Phil Litfraphyjane17No ratings yet

- 21st Assignment 1Document12 pages21st Assignment 1Lovely PitiquenNo ratings yet

- 21st Century ReviewerDocument15 pages21st Century ReviewerKimberly DalagNo ratings yet

- Literary History of Phil Lit (Pre Colonial-Japanese)Document1 pageLiterary History of Phil Lit (Pre Colonial-Japanese)Manuel J. RadislaoNo ratings yet

- Forms of Philipine LiteratureDocument7 pagesForms of Philipine LiteratureJohn Lee Damondon GilpoNo ratings yet

- The Literary Forms in Philippine Literature: Christine F. Godinez-OrtegaDocument7 pagesThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literature: Christine F. Godinez-OrtegaCassy DollagueNo ratings yet

- The Literary Forms in Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesThe Literary Forms in Philippine Literaturenica-chan0% (2)

- Literary Forms in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesLiterary Forms in The PhilippinesKmerylENo ratings yet

- Oral Lore From Pre-Colonial Times ( - 1564) : Mr. Harry Dave B. VillasorDocument22 pagesOral Lore From Pre-Colonial Times ( - 1564) : Mr. Harry Dave B. VillasorJohn Carl AparicioNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Lit Topic For MID-TERMDocument54 pages21st Century Lit Topic For MID-TERMAvegail Constantino0% (1)

- Philippine LiteratureDocument10 pagesPhilippine LiteratureEecya LacisabNo ratings yet

- Periods of Philippine Literature Periods of Philippine LiteratureDocument25 pagesPeriods of Philippine Literature Periods of Philippine Literaturedanica bianca dulayNo ratings yet

- Periods of PH Literature: (Pre-Colonial Period Until The Contemporary Period)Document33 pagesPeriods of PH Literature: (Pre-Colonial Period Until The Contemporary Period)Thalia SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Literature in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesLiterature in The PhilippineskaskaraitNo ratings yet

- Folk-Tales of Angola - Fifty Tales, with Ki-Mbundu Text Literal English Translation Introduction, and NotesFrom EverandFolk-Tales of Angola - Fifty Tales, with Ki-Mbundu Text Literal English Translation Introduction, and NotesNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Self Compassion Exercise PDFDocument3 pagesReflections On Self Compassion Exercise PDFNash PanimbangNo ratings yet

- PRESENT CONTINUOS - Ildefonso - Solis LuisDocument6 pagesPRESENT CONTINUOS - Ildefonso - Solis LuisRaul Osorio DiazNo ratings yet

- Blood PornDocument15 pagesBlood PornSean FinneyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Vlsi Circuits and Systems With CDDocument33 pagesIntroduction To Vlsi Circuits and Systems With CDVishu VishwajaNo ratings yet

- Flirting With Humanity PDFDocument11 pagesFlirting With Humanity PDFValerie WalkerNo ratings yet

- The Subjunctives Bahasa InggrisDocument7 pagesThe Subjunctives Bahasa InggrisMudhoffar SyarifNo ratings yet

- 3 Doors Down - It's Not My Time - Marcada 2Document2 pages3 Doors Down - It's Not My Time - Marcada 2giandeoliveiraNo ratings yet

- Classifications of ArtDocument2 pagesClassifications of ArtAnnaj GabardaNo ratings yet

- Question Paper - PhysicsDocument2 pagesQuestion Paper - Physicsjeru2003No ratings yet

- Indice de HimnosDocument112 pagesIndice de HimnosDulcesMelodíasNo ratings yet

- Absolute Beginner French For Every Day S1 #1 Top 25 French PhrasesDocument5 pagesAbsolute Beginner French For Every Day S1 #1 Top 25 French PhrasesMaurinanfNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Exam1Document2 pagesVocabulary Exam1modernstellarNo ratings yet

- (Quranic/ Classical Written Forms) (Variant With Vowels/ Without Vowels) (Various Spellings)Document19 pages(Quranic/ Classical Written Forms) (Variant With Vowels/ Without Vowels) (Various Spellings)maazaNo ratings yet

- Grammar Review: A B C D e FDocument2 pagesGrammar Review: A B C D e FMireya Menchaca CruzNo ratings yet

- Learn Greek (6 of 7) - The Nominal System, Part IDocument34 pagesLearn Greek (6 of 7) - The Nominal System, Part IBot Psalmerna100% (2)

- Making A Simple and Easy Charcoal Coal ForgeDocument9 pagesMaking A Simple and Easy Charcoal Coal Forgemarius_danila8736No ratings yet

- No-Bling DOTA Mod ReadmeDocument347 pagesNo-Bling DOTA Mod Readmedg dNo ratings yet

- Bruce Lee's Top 10 Rules For SuccessDocument2 pagesBruce Lee's Top 10 Rules For SuccessRamon ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Celebrity CruisesDocument2 pagesCelebrity CruisesDudu LauraNo ratings yet

- Williamson ScriptDocument4 pagesWilliamson ScriptDerek Johnson Jr.No ratings yet

- B-Line CTME-13Document284 pagesB-Line CTME-13Leizer LipaNo ratings yet

- Embelishment Italian TabulationsDocument36 pagesEmbelishment Italian TabulationsMarcelo Cazarotto BrombillaNo ratings yet

- The Nature of The Dream in The Great Gatsby.Document129 pagesThe Nature of The Dream in The Great Gatsby.Dinakaran PDNo ratings yet

- Ernest Renan The Song of Songs PDFDocument180 pagesErnest Renan The Song of Songs PDFanonimo anonimoNo ratings yet

- Internal Diagnostics 605Document10 pagesInternal Diagnostics 605Iliyan HristovNo ratings yet

- Gr6 Syllabus 2019Document11 pagesGr6 Syllabus 2019nirmala somanNo ratings yet

- Manuale Moon IndesitDocument36 pagesManuale Moon IndesitgsaviNo ratings yet

- Narrative ReportDocument1 pageNarrative ReportArvin EleuterioNo ratings yet

- Symmetric Patterns: The Nature of Mathematics and Mathematics in NatureDocument23 pagesSymmetric Patterns: The Nature of Mathematics and Mathematics in NaturejennaNo ratings yet