Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Milan v. EPD Appeals Court Decision

Milan v. EPD Appeals Court Decision

Uploaded by

Courier PressCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Milan v. EPD Appeals Court Decision

Milan v. EPD Appeals Court Decision

Uploaded by

Courier PressCopyright:

Available Formats

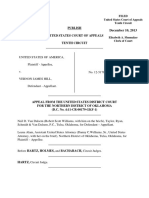

In the

United States Court of Appeals

For the Seventh Circuit

____________________

No. 15-1207

LOUISE MILAN,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

BILLY BOLIN, in his individual capacity as Evansville Police

Department Chief, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

____________________

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Indiana, Evansville Division.

No. 3:13-cv-00001-WTL-WGH William T. Lawrence, Judge.

____________________

ARGUED JUNE 1, 2015 DECIDED JULY 31, 2015

____________________

Before WOOD, Chief Judge, and POSNER and WILLIAMS,

Circuit Judges.

POSNER, Circuit Judge. The plaintiff brought suit against

the City of Evansville, Indiana, and several of the Citys police officers, contending that the police had used excessive

force in the search of her home. The district judge granted

summary judgment in favor of the defendants on related

claims by the plaintiff, but all that is before us is the defend-

No. 15-1207

ants appeal from the district judges denial of their motion

for summary judgment on the excessive-force claim. They

argue that qualified immunity insulates them from liabilitythat is, that there was no established legal principle that

would have informed them that they were using excessive

force.

On June 20, 2012, the Evansville police department became aware of Internet postings that made threats against

the police; a typical posting said New Indiana law. You

have the right to shoot cops. The posts came from an Internet Protocol (IP) address at the home of 68-year-old Louise

Milan and her 18-year-old daughter Stephanie (plus another

daughter who wasnt however at home during the search).

An IP address is like a phone number, but it is a number

that identifies a computer or computer network and so enables a person operating another computer to communicate

with it. The network in Mrs. Milans home was an unsecured

WiFi network, meaning that a person in the vicinity of the

homestanding in the street in front of the house, for examplecould access the network and send messages from it

without needing to know a password. The threats against

the police could have been posted by someone in her house

on her computer, but equally they could have been posted

through the unsecured network by someone near the house.

That the threats might have come from a person (or persons) inside the Milan home who might moreover be armed

and dangerous was enough to make the police decide to

have the house searched by the departments SWAT team

forthwith, though, to repeat, the threatening messages could

instead have emanated from outside the house because of

the open network.

No. 15-1207

The defendants say they didnt know that Mrs. Milans

network was unsecured and therefore accessible by someone

outside the house who could use the unsecured network to

send the threatening messages. Although the police had discovered that there was an unsecured network near the

house, they hadnt bothered to find out whose network it

was, as they could easily have done, precisely because it was

unsecured and therefore accessible. Had they done that they

would have known that it was Mrs. Milans network and,

since it was unsecured, that it might have been used (without her knowledge) by someone outside her home to send

the threatening messages. The failure to discover that the

network was Mrs. Milans was a failure of responsible police

practice.

The search was conducted on June 21, just one day after

the discovery of the posted threats. Shortly before the search,

police had spotted on the porch of a house just two doors

from the Milan house a man named Derrick Murray, whom

they knew to have made threats against the police in the

pastindeed he had been convicted of intimidating a police

officer. At least two of the officers thought him the likeliest

source of the threats. Prudence counseled delaying the

search for a day or so to try to get a better understanding

both of the Milan household and of Murrays potential responsibility for the threats. Prudence went by the board.

Some officers thought, mistakenly as it turned out, that

one or more of three men whose last name was the same as

Mrs. Milans were likely threateners. One of them, Marc Milan, was believed to be a member of a gang and the nephew

of Mrs. Milans deceased husband, though in her deposition

in this case she described him as a near stranger whom she

No. 15-1207

had met for the first time after the search. The second male

Milan, Anthony Milan Sr., was a sex offender who had

committed other types of crime as well. He was Mrs. Milans

stepson and had lived in her house years prior to the search.

The third male Milan, Anthony Milan Jr., was the son of the

second Milan. His Facebook pictures show him holding

guns. He was only an occasional visitor to his stepgrandmothers house.

At the time of the search only Mrs. Milan and her

daughters were living in the house. No man was living, staying, or visiting there, and police surveillance revealed no

man entering or leaving between the threats and the search.

Police did see daughter Stephanie come and go from the

house. She happens to be small for an 18-year-oldone of

the officers who saw her thought she was 13 and the other

that she was 15. Well see that her size and apparent age are

relevant to the appeal.

So: a house occupied by an elderly woman and her two

daughters; no evidence that any criminals would be present

during the search although the possibility could not be excluded entirely; no effort to neutralize suspect Murray during the search, as by posting police to watch his house and

make sure he didnt rush over to Mrs. Milans house when

the search began. But despite their insouciance about Murray and the perfunctory character of their investigation before the search, the police decided to search the Milan

houseand in a violent manner.

A search warrant was applied for and obtained, and the

search was conducted by an eleven-man SWAT team accompanied by a news team. The members of the SWAT team

rushed to the front door of the house, knocked, and without

No. 15-1207

allowing a reasonable timemore than a few secondsfor a

response (though they hadnt gotten a no knock warrant;

see Hudson v. Michigan, 547 U.S. 586, 589 (2006)) broke open

the front door and a nearby window, and through these

openings hurled two flash bang grenades. These are explosive devices, similar to but a good deal less lethal than

military hand grenades, that are intended to stun and disorient persons, thus rendering them harmless, by emitting

blinding flashes of light and deafening sounds. They can kill

if they land on a person, especially a child. The police call

them distraction devices, an absurd euphemism; we called

them bombs in Estate of Escobedo v. Bender, 600 F.3d 770,

78485 (7th Cir. 2010), and United States v. Jones, 214 F.3d 836,

83738 (7th Cir. 2000).

As the flash bangs exploded, the police rushed into the

house, searched it from top to bottom (finding no males, and

also no evidence of any criminal activity), handcuffed mother and daughter, led them out of the house, and questioned

them briefly. (The newsmen did not enter the house; had

they done so, this would have been an independent violation of the Fourth Amendment, Wilson v. Layne, 526 U.S. 603,

611 (1999), because the warrant did not authorize them to

participate in the search.) The mothers and daughters answers to the questions put to them by the police convinced

the police that the women had had nothing to do with the

threats, and so they were released to return to their damaged

and smoking abode. The City of Evansville replaced the broken door and window, and the burned rug, at the Citys expense. There was doubtless other damage; we dont know

whether the City paid for any of it. (Nor do we know the nature and amount of the damages sought by Mrs. Milan in

this suit, though we are guessing that the principal harm for

No. 15-1207

which compensation is sought is emotional. Nor do we

know why Stephanie is not also a plaintiff.)

That no men were found in the house during the raid

confirmed the police in their belief that Murray was responsible for the threats. It took them only a day to discover that

it was indeed he who was responsiblehe had used Mrs.

Milans open network to threaten the police. But rather than

give him the SWAT-team treatment, the police politely requested that he come to police headquarters, which he did,

where he was arrested without incident. (He was prosecuted

for the threats, pleaded guilty, and was given a sixteenmonth prison sentence.) The police departments kid-gloves

treatment of Murray is in startling contrast to their flashbang assault on Mrs. Milans home.

The search of her home was videotaped both by the accompanying news team and by a camera mounted on the

helmet of a member of the SWAT team. The members of the

team are seen on the tapes impressively clad in body armor

and big helmets and carrying formidable rifles pointed forward. It would take a brave criminal to try to fight it out

with them, and of course there was no criminal in the house

and little reason to expect one to be there. The handcuffing

of the daughter, looking indeed much younger than her 18

years, is shown on the helmet video along with the rest of

the search, and she is so small, frail, utterly harmless looking, and completely unresisting that the sight of her being

led away in handcuffs is disturbing. All that the SWAT officer had to do was take her by the hand and lead her out of

the house, which was rapidly filling with smoke from the

flash bangs; there was no conceivable reason to handcuff

her. From what we can observe on the videos, all the mem-

No. 15-1207

bers of the SWAT team were white, Mrs. Milan and her

daughter black; the broadcasting of the videotape cannot

have helped race relations in Evansville.

Police are not to be criticized for taking threats against

them and their families seriously. But flash bangs are destructive and dangerous and not to be used in a search of a

private home occupied so far as the police knew only by an

elderly woman and her two daughters. We cannot understand the failure of the police, before flash banging the

house, to conduct a more extensive investigation of the actual suspects: Murray, living two doors away from the Milan

home and thus with ready access to Mrs. Milans open network, and the male Milans. The police neglect of Murray is

almost incomprehensible. His past made him a prime suspect. A day of investigating him would have nailed him, as

we know because a day of investigatingthe day after the

violent search of the homedid nail him. The district

judges denial of the defendants motion for summary judgment appears eminently reasonable when one puts together

the flash bangs, the skimpy basis for the search and its

prematuritythe failure to check whether the network was

open and the failure to conduct a more extensive investigation before deciding that flash bangs were appropriate

means of initiating the search, the resulting neglect of Murray, and the handcuffing of the daughter.

True, we mustnt base our decision on the wisdom of

hindsight. If the police had had reasonable grounds for conducting the search as they did (that is, with flash bangs, yet

without any but the most perfunctory, indeed radically incomplete, preliminary investigation), then the doctrine of

qualified immunity would shield them from liability even

No. 15-1207

though the flash bangs and ensuing search yielded no benefits for law enforcement. But, to repeat for emphasis, the police acted unreasonably and precipitately in flash banging

the house without a minimally responsible investigation of

the threats. The open network expanded the number of possible threateners and just one extra day of surveillance, coupled with a brief investigation of Murray and the three male

Milans, should have been sufficient to reassure the police

that there were no dangerous men lurking in the house.

Precipitate use of flash bangs to launch a search has troubled us before, leading us to declare that the use of a flash

bang grenade is reasonable only when there is a dangerous

suspect and a dangerous entry point for the police, when the

police have checked to see if innocent individuals are

around before deploying the device, when the police have

visually inspected the area where the device will be used

and when the police carry a fire extinguisher. Estate of Escobedo v. Bender, supra, 600 F.3d at 78485. The police in this

case flunked the test just quoted. True, theyd brought a fire

extinguisher with thembut, as if in tribute to Mack Sennetts Keystone Kops, they left it in their armored SWAT vehicle.

So while the defendants are correct to point out that a

reasonable mistake committed by police in the execution of a

search is shielded from liability by the doctrine of qualified

immunity, Anderson v. Creighton, 483 U.S. 635, 641 (1987), in

this case the Evansville police committed too many mistakes

to pass the test of reasonableness.

AFFIRMED

You might also like

- Digested Cases - Rights of The AccusedDocument9 pagesDigested Cases - Rights of The AccusedNullus cumunisNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing ReviewerDocument57 pagesLegal Writing ReviewerMikee Macalalad75% (4)

- 1 Bar Exam Questions Civil Law Review 1 Persons and Family RelationsDocument29 pages1 Bar Exam Questions Civil Law Review 1 Persons and Family RelationsCalderón Gutiérrez Marlón PówanNo ratings yet

- The Most Surprising Crime Zone: Your Own HomeFrom EverandThe Most Surprising Crime Zone: Your Own HomeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- People vs. MangalinoDocument13 pagesPeople vs. MangalinoRudejane TanNo ratings yet

- Crim Law 1 - Santos Bunachita - For DreiDocument8 pagesCrim Law 1 - Santos Bunachita - For DreiJosiah BalgosNo ratings yet

- People v. DagpinDocument10 pagesPeople v. DagpinSei KawamotoNo ratings yet

- Crim 5digestsDocument3 pagesCrim 5digestsRuby CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- 10 12 1Document3 pages10 12 1CianneNo ratings yet

- People vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr. (Case Digest) : The FactsDocument9 pagesPeople vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr. (Case Digest) : The FactsPhilip JamNo ratings yet

- United States v. Hill, 10th Cir. (2014)Document35 pagesUnited States v. Hill, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lou and Jonbenet: A Legendary Lawman's Quest to Solve a Child Beauty Queen's MurderFrom EverandLou and Jonbenet: A Legendary Lawman's Quest to Solve a Child Beauty Queen's MurderRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- PP Vs SallinasDocument4 pagesPP Vs Sallinascashielle arellanoNo ratings yet

- People vs. SalinasDocument3 pagesPeople vs. SalinasArvy AgustinNo ratings yet

- HeinonlineDocument92 pagesHeinonlineBhanu UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee vs. vs. Accused-Appellant: First DivisionDocument5 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee vs. vs. Accused-Appellant: First DivisionJian CerreroNo ratings yet

- People v. Escordial (2002)Document2 pagesPeople v. Escordial (2002)Alexis Dominic San ValentinNo ratings yet

- Cases 4th PartialDocument167 pagesCases 4th PartialDenzhu MarcuNo ratings yet

- Parrish Complaint ExhibitsDocument64 pagesParrish Complaint ExhibitsAnonymous GF8PPILW5No ratings yet

- Case LifeDocument4 pagesCase LifeDivina Valencia De ButonNo ratings yet

- People vs. Martinez G.R. No. 116918 June 19, 1997Document2 pagesPeople vs. Martinez G.R. No. 116918 June 19, 1997James Andrew Buenaventura100% (1)

- Keith Dana Arrest StatementDocument2 pagesKeith Dana Arrest StatementWSETNo ratings yet

- People vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr. (Case Digest) : - Related Posts at The Bottom of ArticleDocument9 pagesPeople vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr. (Case Digest) : - Related Posts at The Bottom of ArticleJayson AbabaNo ratings yet

- Facts:: People Vs GalitDocument5 pagesFacts:: People Vs GalitNes MejiNo ratings yet

- 9 Title 9 CompleteDocument59 pages9 Title 9 Completesgonzales100% (1)

- 2.people V Salvatierra DigestDocument2 pages2.people V Salvatierra DigestGlen BasiliscoNo ratings yet

- Stewart V R 2011Document7 pagesStewart V R 2011Claudine BaileyNo ratings yet

- People vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr. (Case Digest) - LawCenterDocument6 pagesPeople vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr. (Case Digest) - LawCenterAbs PangaderNo ratings yet

- Dad's Term Paper For Human RightsDocument12 pagesDad's Term Paper For Human RightsRay Faltado100% (1)

- Kunkle v. Cablenews AmericanDocument2 pagesKunkle v. Cablenews AmericanJASON BRIAN AVELINONo ratings yet

- Howard County Police Statement On Swatting TDocument2 pagesHoward County Police Statement On Swatting TWJLA-TVNo ratings yet

- Article 12 RPC DigestDocument6 pagesArticle 12 RPC DigestNeil MayorNo ratings yet

- City of Manila Vs Del Rosario & People vs. CabuangDocument2 pagesCity of Manila Vs Del Rosario & People vs. CabuangReyes OdessaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Reanzares 334 Scra 624 FactsDocument7 pagesPeople vs. Reanzares 334 Scra 624 FactsEdward Kenneth KungNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law DigestsDocument146 pagesCriminal Law DigestsJan Cyril Bulawan DelfinNo ratings yet

- People vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr.Document9 pagesPeople vs. Claudio Teehankee, Jr.Dane Pauline AdoraNo ratings yet

- Crim 1 Digest 2.1.19Document30 pagesCrim 1 Digest 2.1.19Ever AlcazarNo ratings yet

- Fuller AffidavitDocument3 pagesFuller AffidavitAnonymous XetrNzNo ratings yet

- Evidence Rule 30 CDocument8 pagesEvidence Rule 30 CBayani KamporedondoNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit: FiledDocument19 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit: FiledScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People V Tundag DigestDocument2 pagesPeople V Tundag DigestLiana AcubaNo ratings yet

- Sombilon, JR., vs. People (Digest)Document2 pagesSombilon, JR., vs. People (Digest)Tini GuanioNo ratings yet

- JURIS Qualified RapeDocument10 pagesJURIS Qualified RapeAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: TH THDocument43 pagesExecutive Summary: TH THPriscila LópezNo ratings yet

- United States v. Hill, 10th Cir. (2013)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Hill, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Michael Palanay y MinisterDocument16 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Michael Palanay y MinisterKatherine DizonNo ratings yet

- CHIMBALA V THE PEOPLE 1986-zmsc-4Document5 pagesCHIMBALA V THE PEOPLE 1986-zmsc-4Bupe NkanduNo ratings yet

- People V Andan 1997Document22 pagesPeople V Andan 1997Queenie SabladaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 105316 September 21, 1995 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, RENE LAMSING Y JABON, Accused-AppellantDocument5 pagesG.R. No. 105316 September 21, 1995 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, RENE LAMSING Y JABON, Accused-AppellantJoseph John Santos RonquilloNo ratings yet

- People Vs LamsingDocument5 pagesPeople Vs LamsingJoseph John Santos Ronquillo100% (1)

- Trial Room DecisionDocument45 pagesTrial Room DecisionNew York Daily NewsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 116437 March 3, 1997, 269 SCRA 95 Exclusionary RuleDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 116437 March 3, 1997, 269 SCRA 95 Exclusionary RuleRenz Aimeriza AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Dana Williamson v. Florida DOC, 11th Cir. (2015)Document20 pagesDana Williamson v. Florida DOC, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Warren V District of Columbia (D.C. 1981)Document13 pagesWarren V District of Columbia (D.C. 1981)Michael JamesNo ratings yet

- Sergeant Charged With Various Felonies: Man Surrenders To Police SquadDocument28 pagesSergeant Charged With Various Felonies: Man Surrenders To Police SquadcommcreateNo ratings yet

- United States v. Minners, 10th Cir. (2010)Document16 pagesUnited States v. Minners, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Extra Judicial Confession JurisprudenceDocument4 pagesExtra Judicial Confession JurisprudenceRhodail Andrew CastroNo ratings yet

- 40 Case DigestDocument23 pages40 Case DigestEzer Jan Naraja De LeonNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Art National Manufacturers Distributing Co., Louis Watch Co., Louis Friedman, Martin Friedman and Albert Friedman v. Federal Trade Commission, 298 F.2d 476, 2d Cir. (1962)Document3 pagesIn The Matter of Art National Manufacturers Distributing Co., Louis Watch Co., Louis Friedman, Martin Friedman and Albert Friedman v. Federal Trade Commission, 298 F.2d 476, 2d Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Fisher, Dewitt, Perkins and Brady For Appellant. Attorney-General Villa-Real For AppelleeDocument15 pagesFisher, Dewitt, Perkins and Brady For Appellant. Attorney-General Villa-Real For AppelleeKarisse ViajeNo ratings yet

- Cathleen R. Gary v. United States Government, 11th Cir. (2013)Document5 pagesCathleen R. Gary v. United States Government, 11th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Reply Re ReconsiderationDocument14 pagesReply Re ReconsiderationrecallcyNo ratings yet

- Judge Kurtis Loy Complaint 10-23-2014Document21 pagesJudge Kurtis Loy Complaint 10-23-2014Conflict GateNo ratings yet

- Rose Chlebda, Administratrix of The Estate of Joseph Chlebda v. H. E. Fortna and Brother, Inc., 609 F.2d 1022, 1st Cir. (1979)Document4 pagesRose Chlebda, Administratrix of The Estate of Joseph Chlebda v. H. E. Fortna and Brother, Inc., 609 F.2d 1022, 1st Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Full Case-Rights of SuspectsDocument132 pagesFull Case-Rights of SuspectsDenise Michaela YapNo ratings yet

- Anderson v. Kimberly-Clark - Order Granting JOPDocument6 pagesAnderson v. Kimberly-Clark - Order Granting JOPSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- GeffonDocument6 pagesGeffonDaniel HopsickerNo ratings yet

- Vicente Del Rosario y Nicolas, Petitioner, vs. People of The PhilippinesDocument13 pagesVicente Del Rosario y Nicolas, Petitioner, vs. People of The PhilippinesJames Jake ParkerNo ratings yet

- Dispute Redressal Mechanism and Institutions in India PDFDocument26 pagesDispute Redressal Mechanism and Institutions in India PDFDeepak AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Eriese Tisdale Death Sentence VacatedDocument15 pagesEriese Tisdale Death Sentence VacatedGary DetmanNo ratings yet

- Rosenbaum Court DocumentsDocument2 pagesRosenbaum Court DocumentsKeegan TrunickNo ratings yet

- Times Leader 03-06-2012Document36 pagesTimes Leader 03-06-2012The Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- 04-15.austria v. MasaquelDocument10 pages04-15.austria v. MasaquelOdette JumaoasNo ratings yet

- United States v. George S. Sitka, 845 F.2d 43, 2d Cir. (1988)Document7 pagesUnited States v. George S. Sitka, 845 F.2d 43, 2d Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People Vs CaoiliDocument68 pagesPeople Vs CaoiliKaye M-BNo ratings yet

- PCGG Vs Judge PenaDocument23 pagesPCGG Vs Judge PenaGladys BantilanNo ratings yet

- Baby Brianna Lopez Briana Robert Walters JRDocument9 pagesBaby Brianna Lopez Briana Robert Walters JRBaby BriannaNo ratings yet

- Southern Cross Cement Vs Phil Cement ManufacturersDocument22 pagesSouthern Cross Cement Vs Phil Cement ManufacturersnazhNo ratings yet

- 6 Organs of The United NationsDocument2 pages6 Organs of The United NationsSakamachi KinjirouNo ratings yet

- Illinois Baptist State Association Case HistoryDocument7 pagesIllinois Baptist State Association Case HistoryGrant GebetsbergerNo ratings yet

- DBP Vs CADocument6 pagesDBP Vs CAIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- LTD CasesDocument45 pagesLTD CasesMuhammad FadelNo ratings yet

- Cebu Shipyard V William LinesDocument6 pagesCebu Shipyard V William LinesHuzzain PangcogaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Medaition CenterDocument10 pagesPhilippine Medaition CenterLRMNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Co Vs House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal (GR Nos. 92191-92192)Document55 pagesCo Vs House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal (GR Nos. 92191-92192)Jamey SimpsonNo ratings yet