Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 viewsAphasia PDF

Aphasia PDF

Uploaded by

Florina AnichitoaeCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Aphasia CheatsheetDocument3 pagesAphasia CheatsheetMolly Fredericks67% (6)

- Dysarthria Assessment and TreatmentDocument6 pagesDysarthria Assessment and Treatmentapi-3705274100% (4)

- Department of Education: Weekly Learning PlanDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Weekly Learning PlanDian LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Aphasia, (Difficulty Understanding) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandAphasia, (Difficulty Understanding) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Speech Pathology TableDocument9 pagesSpeech Pathology TableMartinez_DO100% (7)

- Aphasia and CommunicationDocument118 pagesAphasia and CommunicationkicsirekaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Wernicke'S Aphasia With Jargon: A Case StudyDocument11 pagesTreatment of Wernicke'S Aphasia With Jargon: A Case StudyIvanaNo ratings yet

- Aphasia Reading ListDocument54 pagesAphasia Reading Listwernibroca0% (1)

- To Taste or Not To TasteDocument3 pagesTo Taste or Not To TasteSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ecosystem WorksheetDocument1 pageEcosystem Worksheetrona2250% (2)

- Leena - Lesson Plan On Converting Numbers To BinaryDocument5 pagesLeena - Lesson Plan On Converting Numbers To Binaryapi-28357083640% (5)

- 2017-06ABecerraContreras MREFLDocument8 pages2017-06ABecerraContreras MREFLAlexánder Becerra0% (2)

- Aphasia: Daniel GhosseinDocument15 pagesAphasia: Daniel GhosseinDaniel Ghossein100% (2)

- What Is AphasiaDocument4 pagesWhat Is AphasiaValentina DubNo ratings yet

- Dysarthria, (Motor Speech Disorder) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandDysarthria, (Motor Speech Disorder) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- ORLADocument10 pagesORLACarol CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Aphasia AssessmentDocument96 pagesAphasia AssessmentRahul RoyNo ratings yet

- DysarthriaDocument2 pagesDysarthriaBanjo VergaraNo ratings yet

- Dysarthria and Dysphonia Neuro1Document7 pagesDysarthria and Dysphonia Neuro1Ersya MuslihNo ratings yet

- Aphasia: Hana Nabila Ulfia 1102014118Document14 pagesAphasia: Hana Nabila Ulfia 1102014118hana nabilaNo ratings yet

- Functional DysphoniaDocument5 pagesFunctional DysphoniaCati GallardoNo ratings yet

- AphasiaDocument4 pagesAphasiaannliss!No ratings yet

- A at Motor SpeechDocument5 pagesA at Motor SpeechNini JohannaNo ratings yet

- Speech Disorders & Rehab - ARADocument26 pagesSpeech Disorders & Rehab - ARAASTRID ASTARI AULIANo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Deep Pharyngeal Neuromuscular Stimulation Versus Thermal Gustatory Stimulation in Decreasing Length of Swallow Initiation and Improving Lingual Movements - Maria H WillisDocument54 pagesEffectiveness of Deep Pharyngeal Neuromuscular Stimulation Versus Thermal Gustatory Stimulation in Decreasing Length of Swallow Initiation and Improving Lingual Movements - Maria H WillisconstantineeliaNo ratings yet

- Acquired Apraxia of Speech Treatment Overview PDFDocument12 pagesAcquired Apraxia of Speech Treatment Overview PDFHaroun Krilov-Egbert100% (1)

- Diseases of Esophagus.Document3 pagesDiseases of Esophagus.Isabel Castillo100% (2)

- Post Stroke WritingDocument9 pagesPost Stroke WritingAdi ParamarthaNo ratings yet

- The ICF Body Functions and Structures Related To Speech-Language PathologyDocument10 pagesThe ICF Body Functions and Structures Related To Speech-Language Pathologylinm@kilvington.vic.edu.auNo ratings yet

- Speech Characteristics of Different Types of Dysarthria: by Dr. Somesh Maheshwari, IndoreDocument21 pagesSpeech Characteristics of Different Types of Dysarthria: by Dr. Somesh Maheshwari, IndoreDr. Somesh MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Jim DX Report RedactedDocument3 pagesJim DX Report Redactedapi-543869960No ratings yet

- DysphagiaDocument2 pagesDysphagiaKimberlyLaw95No ratings yet

- Dysarthria AssessmentDocument11 pagesDysarthria AssessmentvviraaNo ratings yet

- 1533 The Dysphagia Toolbox Validated Assessment Tools For Dysphagia in AdultsDocument33 pages1533 The Dysphagia Toolbox Validated Assessment Tools For Dysphagia in AdultsAlvaro Martinez TorresNo ratings yet

- Non-Cleft Causes of Velopharyngeal Dysfunction: Implications For TreatmentDocument10 pagesNon-Cleft Causes of Velopharyngeal Dysfunction: Implications For TreatmentJanice Cheuk Yin LoNo ratings yet

- Dysarthria ChartDocument12 pagesDysarthria ChartTalia Garcia100% (1)

- Assessment and Treatment of Linguistic Deficits PDFDocument96 pagesAssessment and Treatment of Linguistic Deficits PDFJumraini TammasseNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Patient With Aphasia - UpToDate PDFDocument13 pagesApproach To The Patient With Aphasia - UpToDate PDFMiguel Garcia100% (1)

- Aphasia and Apraxia at A GlanceDocument2 pagesAphasia and Apraxia at A GlanceЈован Д. РадовановићNo ratings yet

- Effective SLPDocument10 pagesEffective SLPRené Ignacio Guzmán SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia: A Case For Speech and Language TherapyDocument3 pagesAdductor Spasmodic Dysphonia: A Case For Speech and Language TherapySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ccu PSG en DysphagiaDocument52 pagesCcu PSG en DysphagiaTni JolieNo ratings yet

- Aphasia Therapy Guide: Impairment-Based TherapiesDocument33 pagesAphasia Therapy Guide: Impairment-Based TherapiesCarolina GudiñoNo ratings yet

- How - . - I Train Others in Dysphagia.Document5 pagesHow - . - I Train Others in Dysphagia.Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Motor Speech Skills in Down SyndromeDocument11 pagesMotor Speech Skills in Down SyndromePaulaNo ratings yet

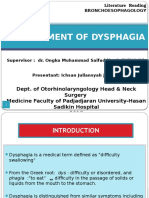

- Management of Dysphagia IjDocument49 pagesManagement of Dysphagia IjIchsanNo ratings yet

- Aphasia TherapyDocument3 pagesAphasia TherapyJustin Jables100% (2)

- Efficacy of Stuttering Therapies - PDF /KUNNAMPALLIL GEJODocument24 pagesEfficacy of Stuttering Therapies - PDF /KUNNAMPALLIL GEJOKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHNNo ratings yet

- 02 Speech Treatment Trail05pubDocument17 pages02 Speech Treatment Trail05pubsbarber7No ratings yet

- Language - NeuroDocument15 pagesLanguage - NeuroAifa Afeeqa Jamilan100% (1)

- AphasiaDocument208 pagesAphasiaErika Velásquez100% (4)

- Dysphagia GeneralDocument36 pagesDysphagia Generaljavi_marchiNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Stuttering TherapiesDocument21 pagesEfficacy of Stuttering Therapiespappu713No ratings yet

- AphasiaDocument194 pagesAphasiagacch24No ratings yet

- APPROACHES TO MANAGEMENT OF FLUENCY DISORDERS - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJODocument150 pagesAPPROACHES TO MANAGEMENT OF FLUENCY DISORDERS - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJOKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHN100% (2)

- SPEECH LANGUAGE PATHOLOGIST DUTES IN IEP - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJODocument136 pagesSPEECH LANGUAGE PATHOLOGIST DUTES IN IEP - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJOKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHN100% (4)

- Clinical Review: Dysarthria, HypokineticDocument19 pagesClinical Review: Dysarthria, HypokineticRashid HussainNo ratings yet

- Vose-Humbert2019 Article HiddenInPlainSightADescriptiveDocument9 pagesVose-Humbert2019 Article HiddenInPlainSightADescriptiveAnna AgenteNo ratings yet

- Global AphasiaDocument5 pagesGlobal AphasiaMuhammad Agus NurNo ratings yet

- Communication and Swallowing Disorders (Speech)Document27 pagesCommunication and Swallowing Disorders (Speech)Asma JamaliNo ratings yet

- Articulation and Phonological Processess SummarisedDocument2 pagesArticulation and Phonological Processess SummarisedSuné GreeffNo ratings yet

- Phonological Process Treatments: Within The Pediatric PopulationDocument85 pagesPhonological Process Treatments: Within The Pediatric PopulationTOBY2No ratings yet

- HBSE 3303 Dysarthria & ApraxiaDocument4 pagesHBSE 3303 Dysarthria & ApraxiasohaimimohdyusoffNo ratings yet

- Harmer - CH 5 - Being Learners2Document32 pagesHarmer - CH 5 - Being Learners2scorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Workshop: Pre Teenagers 12Document3 pagesWorkshop: Pre Teenagers 12scorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Worksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyDocument1 pageWorksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Grand-Bro - Daugh - Un - Ne - Cou - Stra - Mous - Cur - Beau - Good - EyeDocument2 pagesGrand-Bro - Daugh - Un - Ne - Cou - Stra - Mous - Cur - Beau - Good - EyescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Present Perfect ContinuousDocument6 pagesPresent Perfect ContinuousscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Ibagué, Tolima December 28, 2012: Dr. Melba Libia CárdenasDocument2 pagesIbagué, Tolima December 28, 2012: Dr. Melba Libia CárdenasscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Base Form Past Tense Form Past ParticipleDocument2 pagesBase Form Past Tense Form Past ParticiplescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- ScheduleDocument4 pagesSchedulescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Most Children Like Ice Cream.: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezDocument3 pagesMost Children Like Ice Cream.: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- 10 Grade Final Term Test Grammar 1 Complete The Sentences With The Correct Past Form of BeDocument3 pages10 Grade Final Term Test Grammar 1 Complete The Sentences With The Correct Past Form of BescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Grade Topics Addressed:: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezDocument2 pagesGrade Topics Addressed:: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Power Teaching Teaching - TeenagersDocument225 pagesPower Teaching Teaching - Teenagersscorpionmairon100% (3)

- 8th GradersDocument1 page8th GradersscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Worksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyDocument1 pageWorksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- LEVEL ONE: Strawberry Bay: Kindergarten TopicsDocument4 pagesLEVEL ONE: Strawberry Bay: Kindergarten TopicsscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Dialnet MultipleIntelligenceTheoryAndForeignLanguageLearni 919582 PDFDocument18 pagesDialnet MultipleIntelligenceTheoryAndForeignLanguageLearni 919582 PDFFrancisco Perez GomezNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness and HakomiDocument5 pagesMindfulness and HakomiFernando Hilario VillapecellínNo ratings yet

- Understanding Psychology. He Is Also The Author of P.O.W.E.R. Learning and Your Life, FromDocument33 pagesUnderstanding Psychology. He Is Also The Author of P.O.W.E.R. Learning and Your Life, FromRoan Eam TanNo ratings yet

- 4 TSLB3083 - RubricsDocument15 pages4 TSLB3083 - Rubrics卞智瀚No ratings yet

- Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligence ReflectionDocument4 pagesLearning Styles and Multiple Intelligence Reflectionapi-542021228No ratings yet

- Purest Persuasion - Assignment 2Document3 pagesPurest Persuasion - Assignment 2angel 1958No ratings yet

- Literature Review of Specially Designed AcademicDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of Specially Designed Academicapi-325521806No ratings yet

- The Spreen-Benton Aphasia Tests, Normative Data As A Measure of Normal Language Development1Document24 pagesThe Spreen-Benton Aphasia Tests, Normative Data As A Measure of Normal Language Development1Sebastian RiveroNo ratings yet

- Testing Speaking SkillsDocument10 pagesTesting Speaking SkillsFluent English100% (3)

- Mircea Eliade and The Perception of The SacredDocument26 pagesMircea Eliade and The Perception of The SacredRob ThuhuNo ratings yet

- Demonstration: A Teacher Centered StrategyDocument9 pagesDemonstration: A Teacher Centered StrategySujoy GhoshNo ratings yet

- Scie-Chapter 2 Theories, Approaches, Guiding Principles and Methods Act.Document3 pagesScie-Chapter 2 Theories, Approaches, Guiding Principles and Methods Act.Tigerswarch WarriorNo ratings yet

- Perception and Perspective: Prepared by Jerry AndresDocument51 pagesPerception and Perspective: Prepared by Jerry Andresjaypee delacruzNo ratings yet

- ResourcesDocument2 pagesResourcessean_stalleyNo ratings yet

- McCloskey - Advanced Interpretation of The WISC-V and Executive FunctionsDocument242 pagesMcCloskey - Advanced Interpretation of The WISC-V and Executive FunctionsDana Valerdi LozanoNo ratings yet

- Vol 3 No 1 (2021) : EDULINK (Education and Linguistics Knowledge) JournalDocument15 pagesVol 3 No 1 (2021) : EDULINK (Education and Linguistics Knowledge) JournalRestu Suci UtamiNo ratings yet

- 2018 OBE Implementation Guidebook v2Document56 pages2018 OBE Implementation Guidebook v2Vic Key100% (4)

- Memory: Psychology: A Journey, Second Edition, Dennis CoonDocument27 pagesMemory: Psychology: A Journey, Second Edition, Dennis CoonNabeel Riasat Riasat AliNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of The Constructivists ClassroomDocument12 pagesCharacteristics of The Constructivists ClassroomSaneka Setram0% (1)

- Grp4 Kahoot QuestionsDocument6 pagesGrp4 Kahoot QuestionsAnthonette DumbriqueNo ratings yet

- Gonzales, Fatima BSED 2B (Aptitude, Ability, Achievement Test)Document1 pageGonzales, Fatima BSED 2B (Aptitude, Ability, Achievement Test)GONZALES FATIMANo ratings yet

- Music in The Classroom PaperDocument12 pagesMusic in The Classroom Paperrosie_chantal100% (4)

- Chapter 1: Introduction To Discourse Analysis: 1. Form and FunctionDocument5 pagesChapter 1: Introduction To Discourse Analysis: 1. Form and FunctionEmail Tạo Cho VuiNo ratings yet

- Case Study #6: TashaDocument34 pagesCase Study #6: Tashaapi-290117367No ratings yet

- Self Esteem Activities: What Are The Thoughts and Feelings That Support Positive Self Esteem and Confidence?Document6 pagesSelf Esteem Activities: What Are The Thoughts and Feelings That Support Positive Self Esteem and Confidence?Christ Archer SanchezNo ratings yet

- A Review of Research On The Use of Higher Order Thinking Skills To Teach WritingDocument8 pagesA Review of Research On The Use of Higher Order Thinking Skills To Teach WritingAlan Sariadi SuhadiNo ratings yet

- Good General Interview QuestionDocument1 pageGood General Interview QuestionpankajsawardekarNo ratings yet

Aphasia PDF

Aphasia PDF

Uploaded by

Florina Anichitoae0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views4 pagesOriginal Title

52157480-aphasia.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views4 pagesAphasia PDF

Aphasia PDF

Uploaded by

Florina AnichitoaeCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 4

Aphasia

language

voice, speech, language

NIDCD Fact Sheet

u.s. department of health & human services national institutes of health National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

What is aphasia?

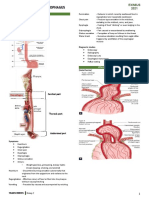

Areas of the brain affected by Brocas and

Wernickes aphasia

Aphasia is a disorder that results from damage to

portions of the brain that are responsible for language.

For most people, these are areas on the left side

(hemisphere) of the brain. Aphasia usually occurs

suddenly, often as the result of a stroke or head injury,

but it may also develop slowly, as in the case of a

brain tumor, an infection, or dementia. The disorder

impairs the expression and understanding of language

as well as reading and writing. Aphasia may co-occur

with speech disorders such as dysarthria or apraxia of

speech, which also result from brain damage.

Who has aphasia?

Anyone can acquire aphasia, including children, but

most people who have aphasia are middle-aged or

older. Men and women are equally affected. According

to the National Aphasia Association, approximately

80,000 individuals acquire aphasia each year from

strokes. About one million people in the United States

currently have aphasia.

What causes aphasia?

Aphasia is caused by damage to one or more of the

language areas of the brain. Many times, the cause of

the brain injury is a stroke. A stroke occurs when blood

is unable to reach a part of the brain. Brain cells die

when they do not receive their normal supply of blood,

which carries oxygen and important nutrients. Other

causes of brain injury are severe blows to the head,

brain tumors, brain infections, and other conditions

that affect the brain.

What types of aphasia are there?

There are two broad categories of aphasia: fluent and

non-fluent.

Damage to the temporal lobe (the side portion) of the

brain may result in a fluent aphasia called Wernickes

aphasia (see figure). In most people, the damage

occurs in the left temporal lobe, although it can result

from damage to the right lobe as well. People with

Wernickes aphasia may speak in long sentences that

have no meaning, add unnecessary words, and even

create made-up words. For example, someone with

Wernickes aphasia may say, You know that smoodle

pinkered and that I want to get him round and take

care of him like you want before. As a result, it is

often difficult to follow what the person is trying to

say. People with Wernickes aphasia usually have great

difficulty understanding speech, and they are often

unaware of their mistakes. These individuals usually

NIDCD Fact Sheet

language

voice, speech

Aphasia

have no body weakness because their brain injury is

not near the parts of the brain that control movement.

A type of non-fluent aphasia is Brocas aphasia. People

with Brocas aphasia have damage to the frontal lobe

of the brain. They frequently speak in short phrases

that make sense but are produced with great effort.

They often omit small words such as is, and, and

the. For example, a person with Brocas aphasia

may say, Walk dog, meaning, I will take the dog

for a walk, or book book two table, for There

are two books on the table. People with Brocas

aphasia typically understand the speech of others fairly

well. Because of this, they are often aware of their

difficulties and can become easily frustrated. People

with Brocas aphasia often have right-sided weakness

or paralysis of the arm and leg because the frontal lobe

is also important for motor movements.

Another type of non-fluent aphasia, global aphasia,

results from damage to extensive portions of the

language areas of the brain. Individuals with global

aphasia have severe communication difficulties and

may be extremely limited in their ability to speak or

comprehend language.

There are other types of aphasia, each of which results

from damage to different language areas in the brain.

Some people may have difficulty repeating words

and sentences even though they can speak and they

understand the meaning of the word or sentence.

Others may have difficulty naming objects even though

they know what the object is and what it may be

used for.

How is aphasia diagnosed?

Aphasia is usually first recognized by the physician

who treats the person for his or her brain injury.

Frequently this is a neurologist. The physician typically

performs tests that require the person to follow

commands, answer questions, name objects, and

carry on a conversation. If the physician suspects

aphasia, the patient is often referred to a speechlanguage pathologist, who performs a comprehensive

examination of the persons communication abilities.

The examination includes the persons ability to speak,

express ideas, converse socially, understand language,

read, and write, as well as the ability to swallow and to

use alternative and augmentative communication.

How is aphasia treated?

In some cases, a person will completely recover from

aphasia without treatment. This type of spontaneous

recovery usually occurs following a type of stroke

in which blood flow to the brain is temporarily

interrupted but quickly restored, called a transient

ischemic attack. In these circumstances, language

abilities may return in a few hours or a few days.

For most cases, however, language recovery is not as

quick or as complete. While many people with aphasia

experience partial spontaneous recovery, in which

some language abilities return a few days to a month

after the brain injury, some amount of aphasia typically

remains. In these instances, speech-language therapy

is often helpful. Recovery usually continues over a twoyear period. Many health professionals believe that the

most effective treatment begins early in the recovery

process. Some of the factors that influence the

amount of improvement include the cause of the brain

damage, the area of the brain that was damaged, the

extent of the brain injury, and the age and health of

the individual. Additional factors include motivation,

handedness, and educational level.

Avoid correcting the persons speech.

Aphasia therapy aims to improve a persons ability to

communicate by helping him or her to use remaining

language abilities, restore language abilities as much

as possible, compensate for language problems, and

learn other methods of communicating. Individual

therapy focuses on the specific needs of the person,

while group therapy offers the opportunity to use new

communication skills in a small-group setting. Stroke

clubs, regional support groups formed by people who

have had a stroke, are available in most major cities.

These clubs also offer the opportunity for people with

aphasia to try new communication skills. In addition,

stroke clubs can help a person and his or her family

adjust to the life changes that accompany stroke

and aphasia.

Allow the person plenty of time to talk.

Help the person become involved outside

the home. Seek out support groups such as

stroke clubs.

Other treatment approaches involve the use of

computers to improve the language abilities of people

with aphasia. Studies have shown that computerassisted therapy can help people with aphasia retrieve

certain parts of speech, such as the use of verbs.

Computers can also provide an alternative system of

communication for people with difficulty expressing

language. Lastly, computers can help people who

have problems perceiving the difference between

phonemes (the sounds from which words are formed)

by providing auditory discrimination exercises.

Family involvement is often a crucial component of

aphasia treatment so that family members can learn

the best way to communicate with their loved one.

What research is being done for aphasia?

Family members are encouraged to:

Simplify language by using short, uncomplicated

sentences.

Repeat the content words or write down key

words to clarify meaning as needed.

Maintain a natural conversational manner

appropriate for an adult.

Minimize distractions, such as a loud radio or TV,

whenever possible.

Include the person with aphasia in conversations.

Ask for and value the opinion of the person with

aphasia, especially regarding family matters.

Encourage any type of communication, whether it

is speech, gesture, pointing, or drawing.

Scientists are attempting to reveal the underlying

problems that cause certain symptoms of aphasia. The

goal is to understand how injury to a particular part

of the brain impairs a persons ability to convey and

understand language. The results could be useful in

treating various types of aphasia, since the treatment

may change depending upon the cause of the

language problem.

Other research is attempting to understand the parts

of the language process that contribute to sentence

comprehension and production and how these parts

may break down in aphasia. In this way, it may be

possible to pinpoint where the breakdown occurs and

help in the development of more focused treatment

programs.

more

smell, taste

voice, speech, language

hearing, balance

Although different languages have many things in

common when specific portions of the brain are

injured, there are also differences. Scientists are trying

to understand the common (or universal) symptoms

of aphasia and the language-specific symptoms of the

disorder. Other researchers are examining whether

people with aphasia may still know their language

but have difficulty accessing that knowledge. These

studies may help with the development of tests

and rehabilitation strategies that focus on specific

characteristics of one language or multiple languages.

Researchers are exploring drug therapy as an

experimental approach to treating aphasia. Some

studies are testing how drugs can be used in

combination with speech therapy to improve recovery

of various language functions.

Researchers are also looking at how treatment of other

cognitive deficits involving attention and memory can

improve communication abilities.

To understand recovery processes in the brain, some

researchers are using functional magnetic resonance

imaging (fMRI) to better understand the human

brain regions involved in speaking and understanding

language. This type of research may improve

understanding of how these areas reorganize after

brain injury. The results could have implications for

both the basic understanding of brain function and the

diagnosis and treatment of neurological diseases.

NIDCD supports and conducts research and research training on the

normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, smell, taste,

voice, speech, and language and provides health information, based

upon scientific discovery, to the public.

Where can I get additional information?

NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that can

answer questions and provide printed or electronic

information on aphasia. Please see the list of

organizations at http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/directory.

Use the following subject areas to help you search for

organizations that are relevant to aphasia:

Aphasia

Speech-language pathologists

Augmentative and alternative communication

For more information, additional addresses and phone

numbers, or a printed list of organizations, contact:

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free Voice: (800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055

E-mail: nidcdinfo@nidcd.nih.gov

NIDCD Fact Sheet: Aphasia

Publication No. 08-4232

Updated October 2008

For more information, contact:

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free Voice:

(800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY:

(800) 241-1055

Fax:

E-mail:

Internet:

(301) 770-8977

nidcdinfo@nidcd.nih.gov

http://www.nidcd.nih.gov

The NIDCD Information Clearinghouse is a service of the

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication

Disorders, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services.

You might also like

- Aphasia CheatsheetDocument3 pagesAphasia CheatsheetMolly Fredericks67% (6)

- Dysarthria Assessment and TreatmentDocument6 pagesDysarthria Assessment and Treatmentapi-3705274100% (4)

- Department of Education: Weekly Learning PlanDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Weekly Learning PlanDian LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Aphasia, (Difficulty Understanding) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandAphasia, (Difficulty Understanding) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Speech Pathology TableDocument9 pagesSpeech Pathology TableMartinez_DO100% (7)

- Aphasia and CommunicationDocument118 pagesAphasia and CommunicationkicsirekaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Wernicke'S Aphasia With Jargon: A Case StudyDocument11 pagesTreatment of Wernicke'S Aphasia With Jargon: A Case StudyIvanaNo ratings yet

- Aphasia Reading ListDocument54 pagesAphasia Reading Listwernibroca0% (1)

- To Taste or Not To TasteDocument3 pagesTo Taste or Not To TasteSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ecosystem WorksheetDocument1 pageEcosystem Worksheetrona2250% (2)

- Leena - Lesson Plan On Converting Numbers To BinaryDocument5 pagesLeena - Lesson Plan On Converting Numbers To Binaryapi-28357083640% (5)

- 2017-06ABecerraContreras MREFLDocument8 pages2017-06ABecerraContreras MREFLAlexánder Becerra0% (2)

- Aphasia: Daniel GhosseinDocument15 pagesAphasia: Daniel GhosseinDaniel Ghossein100% (2)

- What Is AphasiaDocument4 pagesWhat Is AphasiaValentina DubNo ratings yet

- Dysarthria, (Motor Speech Disorder) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandDysarthria, (Motor Speech Disorder) A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- ORLADocument10 pagesORLACarol CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Aphasia AssessmentDocument96 pagesAphasia AssessmentRahul RoyNo ratings yet

- DysarthriaDocument2 pagesDysarthriaBanjo VergaraNo ratings yet

- Dysarthria and Dysphonia Neuro1Document7 pagesDysarthria and Dysphonia Neuro1Ersya MuslihNo ratings yet

- Aphasia: Hana Nabila Ulfia 1102014118Document14 pagesAphasia: Hana Nabila Ulfia 1102014118hana nabilaNo ratings yet

- Functional DysphoniaDocument5 pagesFunctional DysphoniaCati GallardoNo ratings yet

- AphasiaDocument4 pagesAphasiaannliss!No ratings yet

- A at Motor SpeechDocument5 pagesA at Motor SpeechNini JohannaNo ratings yet

- Speech Disorders & Rehab - ARADocument26 pagesSpeech Disorders & Rehab - ARAASTRID ASTARI AULIANo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Deep Pharyngeal Neuromuscular Stimulation Versus Thermal Gustatory Stimulation in Decreasing Length of Swallow Initiation and Improving Lingual Movements - Maria H WillisDocument54 pagesEffectiveness of Deep Pharyngeal Neuromuscular Stimulation Versus Thermal Gustatory Stimulation in Decreasing Length of Swallow Initiation and Improving Lingual Movements - Maria H WillisconstantineeliaNo ratings yet

- Acquired Apraxia of Speech Treatment Overview PDFDocument12 pagesAcquired Apraxia of Speech Treatment Overview PDFHaroun Krilov-Egbert100% (1)

- Diseases of Esophagus.Document3 pagesDiseases of Esophagus.Isabel Castillo100% (2)

- Post Stroke WritingDocument9 pagesPost Stroke WritingAdi ParamarthaNo ratings yet

- The ICF Body Functions and Structures Related To Speech-Language PathologyDocument10 pagesThe ICF Body Functions and Structures Related To Speech-Language Pathologylinm@kilvington.vic.edu.auNo ratings yet

- Speech Characteristics of Different Types of Dysarthria: by Dr. Somesh Maheshwari, IndoreDocument21 pagesSpeech Characteristics of Different Types of Dysarthria: by Dr. Somesh Maheshwari, IndoreDr. Somesh MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Jim DX Report RedactedDocument3 pagesJim DX Report Redactedapi-543869960No ratings yet

- DysphagiaDocument2 pagesDysphagiaKimberlyLaw95No ratings yet

- Dysarthria AssessmentDocument11 pagesDysarthria AssessmentvviraaNo ratings yet

- 1533 The Dysphagia Toolbox Validated Assessment Tools For Dysphagia in AdultsDocument33 pages1533 The Dysphagia Toolbox Validated Assessment Tools For Dysphagia in AdultsAlvaro Martinez TorresNo ratings yet

- Non-Cleft Causes of Velopharyngeal Dysfunction: Implications For TreatmentDocument10 pagesNon-Cleft Causes of Velopharyngeal Dysfunction: Implications For TreatmentJanice Cheuk Yin LoNo ratings yet

- Dysarthria ChartDocument12 pagesDysarthria ChartTalia Garcia100% (1)

- Assessment and Treatment of Linguistic Deficits PDFDocument96 pagesAssessment and Treatment of Linguistic Deficits PDFJumraini TammasseNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Patient With Aphasia - UpToDate PDFDocument13 pagesApproach To The Patient With Aphasia - UpToDate PDFMiguel Garcia100% (1)

- Aphasia and Apraxia at A GlanceDocument2 pagesAphasia and Apraxia at A GlanceЈован Д. РадовановићNo ratings yet

- Effective SLPDocument10 pagesEffective SLPRené Ignacio Guzmán SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia: A Case For Speech and Language TherapyDocument3 pagesAdductor Spasmodic Dysphonia: A Case For Speech and Language TherapySpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ccu PSG en DysphagiaDocument52 pagesCcu PSG en DysphagiaTni JolieNo ratings yet

- Aphasia Therapy Guide: Impairment-Based TherapiesDocument33 pagesAphasia Therapy Guide: Impairment-Based TherapiesCarolina GudiñoNo ratings yet

- How - . - I Train Others in Dysphagia.Document5 pagesHow - . - I Train Others in Dysphagia.Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Motor Speech Skills in Down SyndromeDocument11 pagesMotor Speech Skills in Down SyndromePaulaNo ratings yet

- Management of Dysphagia IjDocument49 pagesManagement of Dysphagia IjIchsanNo ratings yet

- Aphasia TherapyDocument3 pagesAphasia TherapyJustin Jables100% (2)

- Efficacy of Stuttering Therapies - PDF /KUNNAMPALLIL GEJODocument24 pagesEfficacy of Stuttering Therapies - PDF /KUNNAMPALLIL GEJOKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHNNo ratings yet

- 02 Speech Treatment Trail05pubDocument17 pages02 Speech Treatment Trail05pubsbarber7No ratings yet

- Language - NeuroDocument15 pagesLanguage - NeuroAifa Afeeqa Jamilan100% (1)

- AphasiaDocument208 pagesAphasiaErika Velásquez100% (4)

- Dysphagia GeneralDocument36 pagesDysphagia Generaljavi_marchiNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Stuttering TherapiesDocument21 pagesEfficacy of Stuttering Therapiespappu713No ratings yet

- AphasiaDocument194 pagesAphasiagacch24No ratings yet

- APPROACHES TO MANAGEMENT OF FLUENCY DISORDERS - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJODocument150 pagesAPPROACHES TO MANAGEMENT OF FLUENCY DISORDERS - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJOKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHN100% (2)

- SPEECH LANGUAGE PATHOLOGIST DUTES IN IEP - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJODocument136 pagesSPEECH LANGUAGE PATHOLOGIST DUTES IN IEP - PDF / KUNNAMPALLIL GEJOKUNNAMPALLIL GEJO JOHN100% (4)

- Clinical Review: Dysarthria, HypokineticDocument19 pagesClinical Review: Dysarthria, HypokineticRashid HussainNo ratings yet

- Vose-Humbert2019 Article HiddenInPlainSightADescriptiveDocument9 pagesVose-Humbert2019 Article HiddenInPlainSightADescriptiveAnna AgenteNo ratings yet

- Global AphasiaDocument5 pagesGlobal AphasiaMuhammad Agus NurNo ratings yet

- Communication and Swallowing Disorders (Speech)Document27 pagesCommunication and Swallowing Disorders (Speech)Asma JamaliNo ratings yet

- Articulation and Phonological Processess SummarisedDocument2 pagesArticulation and Phonological Processess SummarisedSuné GreeffNo ratings yet

- Phonological Process Treatments: Within The Pediatric PopulationDocument85 pagesPhonological Process Treatments: Within The Pediatric PopulationTOBY2No ratings yet

- HBSE 3303 Dysarthria & ApraxiaDocument4 pagesHBSE 3303 Dysarthria & ApraxiasohaimimohdyusoffNo ratings yet

- Harmer - CH 5 - Being Learners2Document32 pagesHarmer - CH 5 - Being Learners2scorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Workshop: Pre Teenagers 12Document3 pagesWorkshop: Pre Teenagers 12scorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Worksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyDocument1 pageWorksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Grand-Bro - Daugh - Un - Ne - Cou - Stra - Mous - Cur - Beau - Good - EyeDocument2 pagesGrand-Bro - Daugh - Un - Ne - Cou - Stra - Mous - Cur - Beau - Good - EyescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Present Perfect ContinuousDocument6 pagesPresent Perfect ContinuousscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Ibagué, Tolima December 28, 2012: Dr. Melba Libia CárdenasDocument2 pagesIbagué, Tolima December 28, 2012: Dr. Melba Libia CárdenasscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Base Form Past Tense Form Past ParticipleDocument2 pagesBase Form Past Tense Form Past ParticiplescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- ScheduleDocument4 pagesSchedulescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Most Children Like Ice Cream.: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezDocument3 pagesMost Children Like Ice Cream.: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- 10 Grade Final Term Test Grammar 1 Complete The Sentences With The Correct Past Form of BeDocument3 pages10 Grade Final Term Test Grammar 1 Complete The Sentences With The Correct Past Form of BescorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Grade Topics Addressed:: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezDocument2 pagesGrade Topics Addressed:: Colegio Nacional Universitario de VelezscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Power Teaching Teaching - TeenagersDocument225 pagesPower Teaching Teaching - Teenagersscorpionmairon100% (3)

- 8th GradersDocument1 page8th GradersscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Worksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyDocument1 pageWorksheet: Unit 4 Attachment 1 SurveyscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- LEVEL ONE: Strawberry Bay: Kindergarten TopicsDocument4 pagesLEVEL ONE: Strawberry Bay: Kindergarten TopicsscorpionmaironNo ratings yet

- Dialnet MultipleIntelligenceTheoryAndForeignLanguageLearni 919582 PDFDocument18 pagesDialnet MultipleIntelligenceTheoryAndForeignLanguageLearni 919582 PDFFrancisco Perez GomezNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness and HakomiDocument5 pagesMindfulness and HakomiFernando Hilario VillapecellínNo ratings yet

- Understanding Psychology. He Is Also The Author of P.O.W.E.R. Learning and Your Life, FromDocument33 pagesUnderstanding Psychology. He Is Also The Author of P.O.W.E.R. Learning and Your Life, FromRoan Eam TanNo ratings yet

- 4 TSLB3083 - RubricsDocument15 pages4 TSLB3083 - Rubrics卞智瀚No ratings yet

- Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligence ReflectionDocument4 pagesLearning Styles and Multiple Intelligence Reflectionapi-542021228No ratings yet

- Purest Persuasion - Assignment 2Document3 pagesPurest Persuasion - Assignment 2angel 1958No ratings yet

- Literature Review of Specially Designed AcademicDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of Specially Designed Academicapi-325521806No ratings yet

- The Spreen-Benton Aphasia Tests, Normative Data As A Measure of Normal Language Development1Document24 pagesThe Spreen-Benton Aphasia Tests, Normative Data As A Measure of Normal Language Development1Sebastian RiveroNo ratings yet

- Testing Speaking SkillsDocument10 pagesTesting Speaking SkillsFluent English100% (3)

- Mircea Eliade and The Perception of The SacredDocument26 pagesMircea Eliade and The Perception of The SacredRob ThuhuNo ratings yet

- Demonstration: A Teacher Centered StrategyDocument9 pagesDemonstration: A Teacher Centered StrategySujoy GhoshNo ratings yet

- Scie-Chapter 2 Theories, Approaches, Guiding Principles and Methods Act.Document3 pagesScie-Chapter 2 Theories, Approaches, Guiding Principles and Methods Act.Tigerswarch WarriorNo ratings yet

- Perception and Perspective: Prepared by Jerry AndresDocument51 pagesPerception and Perspective: Prepared by Jerry Andresjaypee delacruzNo ratings yet

- ResourcesDocument2 pagesResourcessean_stalleyNo ratings yet

- McCloskey - Advanced Interpretation of The WISC-V and Executive FunctionsDocument242 pagesMcCloskey - Advanced Interpretation of The WISC-V and Executive FunctionsDana Valerdi LozanoNo ratings yet

- Vol 3 No 1 (2021) : EDULINK (Education and Linguistics Knowledge) JournalDocument15 pagesVol 3 No 1 (2021) : EDULINK (Education and Linguistics Knowledge) JournalRestu Suci UtamiNo ratings yet

- 2018 OBE Implementation Guidebook v2Document56 pages2018 OBE Implementation Guidebook v2Vic Key100% (4)

- Memory: Psychology: A Journey, Second Edition, Dennis CoonDocument27 pagesMemory: Psychology: A Journey, Second Edition, Dennis CoonNabeel Riasat Riasat AliNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of The Constructivists ClassroomDocument12 pagesCharacteristics of The Constructivists ClassroomSaneka Setram0% (1)

- Grp4 Kahoot QuestionsDocument6 pagesGrp4 Kahoot QuestionsAnthonette DumbriqueNo ratings yet

- Gonzales, Fatima BSED 2B (Aptitude, Ability, Achievement Test)Document1 pageGonzales, Fatima BSED 2B (Aptitude, Ability, Achievement Test)GONZALES FATIMANo ratings yet

- Music in The Classroom PaperDocument12 pagesMusic in The Classroom Paperrosie_chantal100% (4)

- Chapter 1: Introduction To Discourse Analysis: 1. Form and FunctionDocument5 pagesChapter 1: Introduction To Discourse Analysis: 1. Form and FunctionEmail Tạo Cho VuiNo ratings yet

- Case Study #6: TashaDocument34 pagesCase Study #6: Tashaapi-290117367No ratings yet

- Self Esteem Activities: What Are The Thoughts and Feelings That Support Positive Self Esteem and Confidence?Document6 pagesSelf Esteem Activities: What Are The Thoughts and Feelings That Support Positive Self Esteem and Confidence?Christ Archer SanchezNo ratings yet

- A Review of Research On The Use of Higher Order Thinking Skills To Teach WritingDocument8 pagesA Review of Research On The Use of Higher Order Thinking Skills To Teach WritingAlan Sariadi SuhadiNo ratings yet

- Good General Interview QuestionDocument1 pageGood General Interview QuestionpankajsawardekarNo ratings yet