Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rethinking Surgery in Conflict

Rethinking Surgery in Conflict

Uploaded by

Muhammad Reza0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views2 pagesRethinking Surgery in Conflict from MSF

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRethinking Surgery in Conflict from MSF

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views2 pagesRethinking Surgery in Conflict

Rethinking Surgery in Conflict

Uploaded by

Muhammad RezaRethinking Surgery in Conflict from MSF

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 2

Comment

MSF

Rethinking surgical care in conict

See Editorial page 253

262

The provision of surgical assistance in conict is often

associated with care for victims of violence. Images

of the war wounded from bullets, bomb-blasts, and

other violent assaults often feature prominently in the

mass media. The discipline has been guided by military

surgeons from the developed world who aim to develop

approaches that use the latest surgical technologies in

war zones.1,2 However, in many conicts, the bulk of

surgical care is provided by non-military actors, including

humanitarian organisations, who work with more

limited resources.3

Injury during conict contributes to substantial

mortality, but major causes of excess mortality are often

secondary: cholera, measles, and malnutrition are all

exacerbated by mass population-displacements and

overcrowded conditions for refugees.4,5 Similarly, surgical

needs in conict extend well beyond trauma: mortality

from infection, poor nutrition, obstetric emergencies,

and accidental injuries are all amenable to surgical

intervention. A recent study from the Democratic

Republic of Congo found that mortality from obstetric

emergencies and accidental injury in conict was four

times higher than that from violence.5 In general,

maternal and child mortality is higher in conict-aected

and post-conict countries than in least-developed

countries not directly aected by conict.6

Surgical projects in conicts rarely collect reliable

statistics, but operational data suggests that civilian

surgical needs are predominantly not related to combat.

A retrospective review of surgical services of Mdecins

Sans Frontires in six conict settings found that only

22% (1050) of 4630 surgical interventions were due

to violent injury. Violence represented less than half of

all surgical interventions in conict-aected areas in

Pakistan (5%), South Sudan (21%), Chad (36%), and

Somalia (41%). At almost all sites, obstetric emergencies

vastly outnumbered the war-wounded, accounting for

almost a third (30%) of all interventions, while accidental

injury and tropical infections accounted for another third.

The fact that war-wounded often represent a minority

of surgical needs is not suciently appreciated. A sevencountry review of health services for displaced populations

found that not a single camp had an operating theatre

that could provide life-saving surgery, such as caesarean

section or bowel-rupture repair.7 Other likely needs include

an increase in complications of untreated infectious

diseases, such as bowel perforation from typhoid fever

and soft-tissue abscesses. Limiting surgical humanitarian

assistance to the war-wounded will lead to partial needsassessments, and inadequate programme-planning and

provision of supplies and human resources.

Part of the problem is a lack of reliable data on the

surgical burden of disease in conict settings. No large

population-based surveys have been published, and the

few programme data that exist tend to reect availability

of services rather than population needs. Without reliable

survey data, we cannot know whether an increased

caseload reects an increased disease burden related to

the conict (more road-trac accidents as people ee

conict) or an underlying need that can no longer be met

due to destruction of and limited access to health services.

The bias towards violence-related surgery is reected

in the research eld, which has largely focused on the

specialised surgical care of trauma.8 In view of the dire

shortage of surgeons in resource-limited settings, more

emphasis should be placed on operational research to

support the provision of essential surgical care by general

doctors or non-physician clinicians, particularly because

most essential surgical procedures required in conictaected zones are relatively simple interventions.9

Whereas the emergency public health response to

infectious diseases and malnutrition during conict is

well developed,7 humanitarian practice-guidelines take

a narrow view of surgical needs. The Sphere Project, an

interagency eort dedicated to establishing minimum

standards of humanitarian assistance for disaster

response, limits its guidance for surgical programming

to trauma and obstetric care.10 These guidelines are

under review, which presents an opportunity to more

comprehensively address surgical needs in conict and

postconict settings.

Services to support general surgery in conict settings

are lacking mainly because most conicts occur in leastdeveloped countries where surgical capacity is severely

limited: the poorest third of countries benet from only

35% of global surgical interventions.11 With a growing

appreciation of the substantial burden of surgical

diseases across the developing world,12 the relevance of

the traditional models of surgical assistance for civilians

in conict merits reconsideration.

www.thelancet.com Vol 375 January 23, 2010

Comment

Kathryn Chu, Miguel Trelles, *Nathan Ford

Mdecins Sans Frontires, Braamfontein 2017, Johannesburg,

Gauteng, South Africa (KC, NF); and Mdecins Sans Frontires,

Brussels, Belgium (MT)

nathan.ford@joburg.msf.org

We declare that we have no conicts of interest.

1

2

3

Blackbourne LH. The next generation of combat casualty care. J Trauma

2009; 66 (suppl 4): S2728.

Mellor SG. Military surgery in the 21st century. J R Naval Med Serv 2006;

92: 10913.

Vassallo DJ. The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and

lessons from its experience of war surgery. J R Army Med Corps 1994;

140: 14654.

Depoortere E, Checchi F, Broillet F, et al. Violence and mortality in West

Darfur, Sudan (200304): epidemiological evidence from four surveys.

Lancet 2004; 364: 131520.

Coghlan B, Ngoy P, Mulumba F, et al. Update on mortality in the Democratic

Republic of Congo: results from a third nationwide survey.

Disaster Med Public Health Prepare 2009; 3: 8896.

9

10

11

12

Spiegel PB, Cornier N, Schilperoord M. Funding for reproductive health in

conict and post-conict countries: a familiar story of inequity and

insucient data. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000093.

Spiegel P, Sheik M, Gotway-Crawford C, Salama P. Health programmes

and policies associated with decreased mortality in displaced people in

postemergency phase camps: a retrospective study. Lancet 2002;

360: 192734.

Weber MA, Fox CJ, Adams E, et al. Upper extremity arterial combat injury

management. Persp Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther 2006; 18: 14145.

Chu K, Rosseel P, Gielis P, Ford N. Surgical task shifting in Sub-Saharan

Africa. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000078.

Sphere Project: Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in disaster

response. 2004. http://www.sphereproject.org/content/view/27/84/

lang,english (accessed Nov 18, 2009).

Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the

global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data.

Lancet 2008; 372: 13944.

Debas H, Gosselin RA, McCord C, Thind A. Surgery. In: Jamison D, ed.

Disease control priorities in developing countries, 2nd edn. New York:

Oxford University Press, 2006: 124559.

Ticagrelor in ACS: redening a new standard of care?

Tremendous progress has been achieved over the past

decade in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes

(ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI],

non-STEMI [NSTEMI], and unstable angina). In STEMI,

primary percutaneous coronary intervention compared

with brinolytic therapy reduces mortality, reinfarction,

stroke, infarct size, and recurrent ischaemia.1 In

moderate-risk and high-risk patients with NSTEMI, early

angiography followed by revascularisation with either

percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery

bypass graft surgery compared with a more conservative

approach reduces the rates of death or myocardial

infarction, recurrent ischaemia, and rehospitalisation.2,3

Drug-eluting stents have been shown to be safe in acute

coronary syndromes, and, compared with bare-metal

stents, reduce clinical and angiographic restenosis,4

further improving quality of life. With expeditious

revascularisation recognised as the cornerstone of the

treatment of acute coronary syndromes, selecting the

optimum pharmacotherapeutic regimen to support the

invasive approach becomes imperative. Because platelet

activation is intense in acute coronary syndromes,

percutaneous coronary intervention, and coronary

artery bypass graft surgery, it is not surprising that the

thienopyridine clopidogrel, which inhibits ADP-induced

platelet activation, when added to aspirin further

suppresses ischaemic complications in acute coronary

syndromes.5,6 Prasugrel, which is more potent and rapidacting than clopidogrel, is even better at preventing

www.thelancet.com Vol 375 January 23, 2010

myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis in

patients with an acute coronary syndrome undergoing

percutaneous coronary intervention.7 However, proportional to their potency, these oral agents increase

haemorrhagic complications, the occurrence of which

has been strongly linked to subsequent mortality.8,9

As a result, neither thienopyridine has been shown to

improve survival in acute coronary syndromes.

Enter ticagrelor, an oral non-thienopyridine cyclo-pentyltriazolo-pyrimidine ADP-receptor (P2Y12 antagonist,

which like prasugrel is more potent and rapid-acting than

clopidogrel. In the PLATO trial, this agent was compared

with clopidogrel in more than 18 500 patients with

acute coronary syndromes.10 In The Lancet, today, the

PLATO investigators11 now report the detailed outcomes

in around 13 000 patients (720% of all those enrolled)

managed with an urgent early invasive approach.

Like prasugrel, ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel

signicantly reduced rates of myocardial infarction and

stent thrombosis, accompanied by an increase in major

bleeding that was unrelated to coronary artery bypass

graft surgery. However, that is where the comparison

ends. In TRITON, prasugrel increased bleeding that was

related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery, all-cause

bleeding, and transfusions, as well as life-threatening and

fatal bleeding which largely oset its expected benets

from prevention of myocardial infarction and stent

thrombosis. As a result, total mortality at 15 months was

not signicantly dierent with prasugrel and clopidogrel

Published Online

January 14, 2010

DOI:10.1016/S01406736(10)60070-0

See Articles page 283

263

You might also like

- ATLS Practice Test 2 Answers & ExplanationsDocument8 pagesATLS Practice Test 2 Answers & ExplanationsCarl Sars75% (4)

- School Health Policy in NigeriaDocument40 pagesSchool Health Policy in NigeriaMahalim Fivebuckets100% (5)

- Losing My ReligionDocument4 pagesLosing My ReligionMuhammad Reza100% (1)

- Acticide CL1: ® Technical InformationDocument2 pagesActicide CL1: ® Technical InformationОлександр МацукаNo ratings yet

- Emergency Surgery 2: Perforated Peptic UlcerDocument11 pagesEmergency Surgery 2: Perforated Peptic Ulcerjidottt kejedotNo ratings yet

- 6 Osteoporotic Fractures in Older Adults: Cathleen S. Colo N-EmericDocument12 pages6 Osteoporotic Fractures in Older Adults: Cathleen S. Colo N-EmericRafael CastellarNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion 2Document7 pagesBlood Transfusion 2omarragabselimNo ratings yet

- (HTTP://WWW - Who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/3/11-093732/en/) : Epidemiology of SurgeriesDocument3 pages(HTTP://WWW - Who.int/bulletin/volumes/90/3/11-093732/en/) : Epidemiology of SurgeriesJoy ChalisseryNo ratings yet

- Global Action On Patient SafetyDocument8 pagesGlobal Action On Patient SafetycynthiaNo ratings yet

- 2023 Article 13352Document9 pages2023 Article 13352Rubén LimaNo ratings yet

- Chugh 2013Document61 pagesChugh 2013dharsandipan86No ratings yet

- Late Immune Consequences of Combat Trauma: A Review of Trauma-Related Immune Dysfunction and Potential TherapiesDocument13 pagesLate Immune Consequences of Combat Trauma: A Review of Trauma-Related Immune Dysfunction and Potential TherapiesQariahMaulidiahAminNo ratings yet

- 14 - Towards Best Practice in Acute Stroke Care in Ghana A Survey of Hospital ServicesDocument11 pages14 - Towards Best Practice in Acute Stroke Care in Ghana A Survey of Hospital ServicesChristel CibalonzaNo ratings yet

- Research ProporsalDocument12 pagesResearch ProporsalStanley JuniorNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 66Document8 pages2017 Article 66Zuhratul LathifaNo ratings yet

- Propofol-TIVA Versus Inhalational Anesthesia For Cancer SurgeryDocument9 pagesPropofol-TIVA Versus Inhalational Anesthesia For Cancer SurgerygonjdelzNo ratings yet

- JCO 2014 Ñamendys Silva 1169 70Document2 pagesJCO 2014 Ñamendys Silva 1169 70Eward Rod SalNo ratings yet

- Chest Masive TransfDocument16 pagesChest Masive TransfMacario Ismael Chavez CutzNo ratings yet

- Primary Care For Cancers - Epidemiology, Causes, Prevention and Classification - A Narrative ReviewDocument7 pagesPrimary Care For Cancers - Epidemiology, Causes, Prevention and Classification - A Narrative ReviewChew Boon HowNo ratings yet

- WFSA UpdateDocument60 pagesWFSA UpdateSyaiful FatahNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Clotting Factor Activities Early After Severe Multiple Trauma and Their Correlation With Coagulation Tests and Clinical Data (2015)Document9 pagesEvaluation of Clotting Factor Activities Early After Severe Multiple Trauma and Their Correlation With Coagulation Tests and Clinical Data (2015)Dsm DsmNo ratings yet

- Early Surgery Confers One-Year Mortality Benefit in Hip-Fracture PatientsDocument12 pagesEarly Surgery Confers One-Year Mortality Benefit in Hip-Fracture PatientsMartin MontesNo ratings yet

- (Ghiduri) (Cancer) ACCP Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer - Evidence-Based GuidelinesDocument395 pages(Ghiduri) (Cancer) ACCP Diagnosis and Management of Lung Cancer - Evidence-Based GuidelinesMario AndersonNo ratings yet

- Arthroplasty TodayDocument4 pagesArthroplasty TodayCristina SavaNo ratings yet

- Survival Analysis and Mortality Predictors of Hospitalized Severe Burn Victims in A Malaysian Burns Intensive Care UnitDocument8 pagesSurvival Analysis and Mortality Predictors of Hospitalized Severe Burn Victims in A Malaysian Burns Intensive Care UnitKenjiNo ratings yet

- 10 Facts On Patient SafetyDocument3 pages10 Facts On Patient SafetySafiqulatif AbdillahNo ratings yet

- Splenectomy For Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura: Surgery For The 21st CenturyDocument4 pagesSplenectomy For Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura: Surgery For The 21st Centurykevin stefanoNo ratings yet

- En A10v16n3Document4 pagesEn A10v16n3Just MahasiswaNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Meeting Surgical Needs in The Developing WorldDocument4 pagesChallenges of Meeting Surgical Needs in The Developing WorldTheGongziNo ratings yet

- Picot Synthesis SummativeDocument14 pagesPicot Synthesis Summativeapi-259394980No ratings yet

- The Satisfactionof Patients On Maintenance Hemodialysis Concerning The Provided Nursing Care in Hemodialysis UnitsDocument11 pagesThe Satisfactionof Patients On Maintenance Hemodialysis Concerning The Provided Nursing Care in Hemodialysis Unitsbe a doctor for you Medical studentNo ratings yet

- End of The Road For Heparin Thromboprophylaxis 2016Document3 pagesEnd of The Road For Heparin Thromboprophylaxis 2016Michael FreudigerNo ratings yet

- Jurnal LainDocument22 pagesJurnal LainBudi ArsanaNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion in Critical Care: Giora Netzer, Richard P Dutton and John R HessDocument3 pagesBlood Transfusion in Critical Care: Giora Netzer, Richard P Dutton and John R Hessnevermore11No ratings yet

- Radiation Safety Paper Week 2Document4 pagesRadiation Safety Paper Week 2api-313040758No ratings yet

- Blunt Abdominal TraumaDocument8 pagesBlunt Abdominal TraumaYudis Wira PratamaNo ratings yet

- Pre Hos TraumaDocument11 pagesPre Hos TraumaGel OmugtongNo ratings yet

- Surgery Public Health and PakistanDocument10 pagesSurgery Public Health and PakistanFatima ColonelNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Risk Factors of Lymph Edema in Breast Cancer PatientsDocument8 pagesResearch Article: Risk Factors of Lymph Edema in Breast Cancer PatientsidaNo ratings yet

- Acute ProctitisDocument3 pagesAcute ProctitisAdreiTheTripleANo ratings yet

- Simou Non-Blood Medical Care in Gynecologic... (22051161) World J Surg Oncol 2011 9 142Document6 pagesSimou Non-Blood Medical Care in Gynecologic... (22051161) World J Surg Oncol 2011 9 142Walter Ramos TelesNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 329Document6 pages2016 Article 329anon_242145531No ratings yet

- 31 - Can Older Adults Benefitfrom Smart Devices, Wearables, and Other DigitalHealth Options To EnhanceCardiac RehabilitationDocument9 pages31 - Can Older Adults Benefitfrom Smart Devices, Wearables, and Other DigitalHealth Options To EnhanceCardiac RehabilitationMariaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673616314878 MainDocument1 page1 s2.0 S0140673616314878 MainAntzela MoumtziNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Gastric CancerDocument2 pagesPrevention of Gastric CancerAndhika Bintang MahardhikaNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Needs Large International Clinical Trials: Mcmaster University, Ontario, CanadaDocument4 pagesAnesthesia Needs Large International Clinical Trials: Mcmaster University, Ontario, Canadaserena7205No ratings yet

- Damage Control Management y Polytrauma PatientDocument324 pagesDamage Control Management y Polytrauma PatientMauri ParadedaNo ratings yet

- Wound Management For The 21st Century: Combining Effectiveness and EfficiencyDocument11 pagesWound Management For The 21st Century: Combining Effectiveness and EfficiencyHeba VerebceanNo ratings yet

- IPHMILitRev V5.2Document5 pagesIPHMILitRev V5.2miguel angel camachoNo ratings yet

- Who 2016 PDFDocument2 pagesWho 2016 PDFRefialy WahyyNo ratings yet

- Malignidad Post TrasplanteDocument7 pagesMalignidad Post TrasplantePao MoralesNo ratings yet

- Sepsis 2016 PDFDocument10 pagesSepsis 2016 PDFRicardo Ortiz NovilloNo ratings yet

- Blood in TraumaDocument17 pagesBlood in TraumaEmtha SeeniNo ratings yet

- Noncompliance in Organ Transplant Recipients A Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesNoncompliance in Organ Transplant Recipients A Literature ReviewtkpmzasifNo ratings yet

- Critical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesFrom EverandCritical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesDmitri BezinoverNo ratings yet

- Patient Selection in Ambulatory Surgery: Jeremy Lermitte and Frances ChungDocument5 pagesPatient Selection in Ambulatory Surgery: Jeremy Lermitte and Frances ChungMartin Víctor Flores JimenezNo ratings yet

- Martin 2005Document23 pagesMartin 2005Petrucio Augusto SDNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Efusi Pleura MalignaDocument12 pagesJurnal Efusi Pleura MalignaAsyraf HabibieNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guide SEOM On Venous Thromboembolism in Cancer PatientsDocument12 pagesClinical Guide SEOM On Venous Thromboembolism in Cancer PatientsGaby ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- 775 FullDocument9 pages775 FullidaNo ratings yet

- First Draft DVT ProphylaxisDocument6 pagesFirst Draft DVT ProphylaxisRundNo ratings yet

- Mortality and Infectious Complications of Therapeutic Endovascular Interventional Radiology: A Systematic and Meta-Analysis ProtocolDocument8 pagesMortality and Infectious Complications of Therapeutic Endovascular Interventional Radiology: A Systematic and Meta-Analysis ProtocolgtNo ratings yet

- Cancer Screening in the Developing World: Case Studies and Strategies from the FieldFrom EverandCancer Screening in the Developing World: Case Studies and Strategies from the FieldMadelon L. FinkelNo ratings yet

- Resident On Call PDFDocument143 pagesResident On Call PDFMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22: Lacerations and Scar Revision Terence M. Davidson Lacerations Wound ClassificationsDocument16 pagesChapter 22: Lacerations and Scar Revision Terence M. Davidson Lacerations Wound ClassificationsMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- The Four Imams by Muhammad Abu ZahraDocument3 pagesThe Four Imams by Muhammad Abu ZahraMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Radical ReformDocument1 pageRadical ReformMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Is The Bible The Word of God-718314Document37 pagesIs The Bible The Word of God-718314Muhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- The Four MadhabDocument1 pageThe Four MadhabMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Tokyo Guideline 2018 - Cholecystitis (Small Size)Document69 pagesTokyo Guideline 2018 - Cholecystitis (Small Size)Muhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal On Hand SurgeryDocument187 pagesJurnal On Hand SurgeryMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Closed Reduction of Posterior Hip DislocationDocument4 pagesClosed Reduction of Posterior Hip DislocationMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Amputation Guideline EN PDFDocument3 pagesAmputation Guideline EN PDFMuhammad RezaNo ratings yet

- Discipline Code and Student Behavioral Contract: Parent SectionDocument2 pagesDiscipline Code and Student Behavioral Contract: Parent Sectionsir jjNo ratings yet

- Lasso GBRDocument1 pageLasso GBRMohamedAtefNo ratings yet

- Rhinomicosis IndiaDocument4 pagesRhinomicosis IndiaLiz TorresNo ratings yet

- (Report) Medication ErrorDocument4 pages(Report) Medication ErrorJoyce TanNo ratings yet

- Illustrated Objective Toxicology For Veterinary Exams - (WWW - FreeBookBank.net) PDFDocument99 pagesIllustrated Objective Toxicology For Veterinary Exams - (WWW - FreeBookBank.net) PDFAshok BalwadaNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Panchakarma KSR 2-2-13Document49 pagesAesthetic Panchakarma KSR 2-2-13Technoayurveda DrksrprasadNo ratings yet

- Course CatalogDocument456 pagesCourse CatalogIan Xavier GalloNo ratings yet

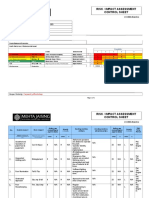

- Risk / Impact Assessment Control Sheet: CC/EHS/RA/014 ContractDocument4 pagesRisk / Impact Assessment Control Sheet: CC/EHS/RA/014 Contractsaurabh juwatkarNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practicum Worksheet: Nursing Care PlanDocument4 pagesClinical Practicum Worksheet: Nursing Care PlanOrlea Francisco-SisioNo ratings yet

- Specification - ISOMALT LM - V007Document4 pagesSpecification - ISOMALT LM - V007Hakan ÇİÇEKNo ratings yet

- 7 Day Intermittent Fasting Meal PlanDocument11 pages7 Day Intermittent Fasting Meal Plandietbykt.planshareNo ratings yet

- Soket ProstesisDocument7 pagesSoket ProstesisAnantaNo ratings yet

- Cloning Technology-Bane or Boon To MankindDocument52 pagesCloning Technology-Bane or Boon To MankindDevain AroraNo ratings yet

- Biofeedback Training For Enhanced Trading PerformanceDocument5 pagesBiofeedback Training For Enhanced Trading PerformancejNo ratings yet

- Reportpdf1 PDFDocument3 pagesReportpdf1 PDFLifetime AbbeyNo ratings yet

- Msds Citrapure - DryDocument2 pagesMsds Citrapure - DryKyle MccoyNo ratings yet

- Elektrokardiografi: DR - Dr. Zaenal Muttaqien Sofro,, AIFM, Sport & Circ - Med School of Medicine Gadjah Mada UniversityDocument71 pagesElektrokardiografi: DR - Dr. Zaenal Muttaqien Sofro,, AIFM, Sport & Circ - Med School of Medicine Gadjah Mada UniversityNadyaNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument14 pagesAnnotated BibliographyDrew TilleyNo ratings yet

- p450 Table Oct 11 2009Document2 pagesp450 Table Oct 11 2009Naresh BabuNo ratings yet

- EHS 085 General Security Procedure For Manufacturing Area SampleDocument3 pagesEHS 085 General Security Procedure For Manufacturing Area Samplerozario100% (1)

- Meniscus TearsDocument29 pagesMeniscus Tearsmaulana ilhamNo ratings yet

- Rituximab Protocol PDFDocument13 pagesRituximab Protocol PDFSenarathKuleeshaKodisinghe100% (1)

- Provincial Veterinary Office: Republic of The Philippines Province of CebuDocument2 pagesProvincial Veterinary Office: Republic of The Philippines Province of CebuKyle Dhon Estrera VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Polysomnograpy: Charmain Beatriz A. AtosDocument62 pagesPolysomnograpy: Charmain Beatriz A. AtosCharmain Beatriz Ayson Atos100% (2)

- Contoh Soal PG Bahasa Inggris Kelas XI Semester 1 K13 Beserta JawabanDocument12 pagesContoh Soal PG Bahasa Inggris Kelas XI Semester 1 K13 Beserta JawabanIntan Wahyu DhamayantiNo ratings yet

- Oldenburg Burnout Inventory ScoringDocument3 pagesOldenburg Burnout Inventory ScoringAnonymous 0uCHZz72vwNo ratings yet

- Hypernatremia: Kidney Case Conference: How I TreatDocument3 pagesHypernatremia: Kidney Case Conference: How I TreatJulian ViggianoNo ratings yet