Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Craik-Supermodels and Super Bodies

Craik-Supermodels and Super Bodies

Uploaded by

Anonymous ec9pxm0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

189 views6 pagesGender Inequality

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentGender Inequality

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

189 views6 pagesCraik-Supermodels and Super Bodies

Craik-Supermodels and Super Bodies

Uploaded by

Anonymous ec9pxmGender Inequality

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 6

36

JENNIFER CRAIK

Supermodels and Super Bodies

From J. Craik (1994), The Face of Fashion

(London and New York: Routledge), 85-91.

Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Books UK.

‘Whereas models had been an adjunct to the

fashion industry, by the 1960s they were syn-

conymous with it.! The status of modeling reached

a zenith, Individual models became household

names and international personalities. Twiggy,

for example, was named “Woman of the Year”

in 1966, an unthinkable occurrence previously.

By the 1970s, models had become superstars, a

trend that continued into the 1980s and 1990s,

Supermodels were well-paid, high-profile, inter

national jet-setvers.

‘Their changing status was reflected in their

earning power. American models earned about

$25 a day in the 1940s. This had increased to

$5,000 a day for a top model in the 1970s, and

to between $15,000 and $25,000 a day by 1990

Highly successful models carned $250,000 a

year, while about thirty earned $500,000, and a

handful $2.5 million annually (Rudolph 1991:

72). Despite the porential earning power, most

models have difficulty sustaining a regular in-

come. Not only must potential models conform

to ctiteria about their bodies, they must develop

a distinctive trademark in their worl. Crucial

to the model is an updated portfolio of studio

shots, “tear sheets” (ftom jobs they have done)

plus a “head sheet” that includes vital statistics

and rates, Modeling jobs are usually contracted

through agencies that send out details of suitable

models. Alchough models emphasize their indi-

vidual attractions, they are usually chosen for jobs

depending on whether they are “the right type”

for the client and the clothes. Even top models

endure “go-sees” and rejections (Hartman 1980:

64). The body becomes an all-consuming obses-

sion for models and their coworkers. Models are

judged on the “perfection” of their body, yet are

considered unintelligent because of it. Lauren

Hutton commented:

ve met people who apparently fele that by vireue

of being attractive, Iwas dumb. les still a prevalent

cliché. Unfortunately by being ateractive, women

can get what they want; they don't develop their

personalities or sense of humor. But it’s a stifling

way co live. Who wants to just sit around and be

vacuous? (quoted by Hartman 1980: 64)

Naomi Campbell has also described the frustra-

tion of being taken at “face value”—as being no

more than her image as a model:

Part of the problem is that people only take mod-

els at face value, In a way, what we do is like act-

ing, except that we don't speak. Because we don't

speak, we don't have anything to say. What we ry

to do is project all our emotion and personalicy

through our faces, but that can be misconstrued.

“These pictures are poses, that is not what we are

like in real life ar all. We are women too; we have

feelings. When you have a very visual job, your ap-

pearance is taken to be che most important thing

about you. There is no defence. (quoted by L-A

Jones 1992: 10)

Moreover, the ideal body changes and models

can be displaced overnight should their “look”

go out of fashion. [Jean] Shrimpton discovered

on a shoot in Portugal thet she was becoming a

has-been when the other model, the Dutch-born

Willie, was given the best clothes and more shots

because she was younger and fresher. Shrimpton’s

reaction was one of powerlessness: “Even today

Tam not orally free of the sense of being a has-

been” (Shrimpton 1990: 161). Modeling is a

risky and transient business

Each decade becomes associated with @ par-

ticular image of femininity and of particular

models who capture that look. Sometimes the

look is associated with national images. Katie

Ford of the Ford Agency identified German mod-

els with the 1960s, Italians with the 1970s, and

English and Australians with the 1980s (Sheehan

1986: 64). These caricatures do not reflect the

employment patterns in the industry as much as

the encapsulation of successive idealized “looks.”

Even so, most of the successfull models have con-

formed to Western stereotypes of beauty because

“in every country, blond hair and blue eyes sell”

(Radolph 1991: 72). Although the majority of

models are still white, the supermodels include

some diverse looks and ethnicities. Even so, non-

white models still experience ambivalence toward

them within the industry. English-born black

model Naomi Campbell suspected that many re-

sented the fact that she has succeeded as a “black

tulip” rather than a “typical English rose":

I should think that the people who really care

about those things despise having me, a black

tulip! Things are changing, of course, but will a:

ways be slow, Not a lot of ethnic girl-—Hispan-

ies, blacks, Japanese—do the endorsements, get

awarded the big cosmetic contracts, We'e good

enough to model clothes, do the pictures, bur

that’s it. (quoted by L.-A. Jones 1992: 10)

As the status of models has changed, so too has

the profession. The dissolution of the distinction

between runway and photographic models re-

quires models who are flexible, have diverse skills

and are more competitive. Successful models

SUPERMODELS AND SUPER BODIES | 283

maintain a disciplined regime of body rituals to

maximize their attributes, including constant

dieting, exercise, massages, saunas, manicures

and pedicures. At the Miss Venezuela Academy,

which has produced four Miss Worlds, three Mi

Universes and countless runners-up in the past

decade, selected applicants are offered free acro-

bics training, diet advice, dental work, makeup

applications, hairstyling, and “the latest range of

cosmetic surgery’—a popular option (Perrottet,

1993). “Getting the look” is one thing; keeping

it is another, Elle MacPherson attributes her suc-

cess to discipline—diet, exercise and punctual-

ity—starting each day with 500 sit-ups and three

liters of water (Lyons 1992: 12)

Despite, or perhaps because of, the enormous

investment in their bodies, few models admit to

being beautiful. Rathes, they seem to be chroni-

cally dissatisfied with their looks. Even super-

model Cindy Crawford said: “Ie’s hard doing a

runway show. You're surrounded by forty of the

most beautiful women in the world, You see

all your own imperfections and none of theirs”

(quoted by Rudolph 1991:74). Models separate

their “professional” bodies from their “lived-in”

ones, regarding them as alien, One fourceen-

year-old model commented on her first photo-

graphs for Elle:

“There was a lot of mucking around. You never re-

ally know how ies going to turn out. I was pleased

with the pictures. But irs hard to relate them to

being me. Theres me at school and there's me in

the magazine—they'te completely different. (Safe

1990: 24)

Even top models are not immune from this

sense of alienation and dissatisfaction. Although

dubbed by Time magazine as “The Body of Our

Time,” Elle MacPherson has said:

I dont particularly like the way I look, co tell you

the truth ... often think I'm smarter than 1 look

When you're trying to sell how beautiful you

are and you don't think you're that beautiful, i?

a bit scary. I have an image that’s approachable to

the public and ic sells. Thac’s great but it’s differ-

cent from being the most beautiful woman in the

284 | JENNIFER CRAIK

world. I know damn well what I see. (quoted by

Wyndham 1990: 23-4)

“The obsession with their looks breeds extreme

insecurity. Shrimpton recalled:

J was bored, and we must have been exceedingly

boring co others. I found life trivial then, and look

ing back I do not understand why I stuck with ic

We were so vain that we continued co dress our

selves up and go out o be looked at... Iwas so i

secure that I was always fiddling in the bathroom

or running to the ladies to check my appearance.

Ik was pathetic! Here I was, at the height of my

fame, behaving like this, I was just an accessory.

(Shrimpton 1990: 102)

Yer modeling continues to attract many young,

girls as a potentially glamorous and lucrative

career. Many models are starting in their early

ceens. Photographers like them because they are

still chin with perfect skin and clear eyes (Safe

1990: 26). Moreover, they are “fresh” and un-

trained in the conventional poses and gestures

of experienced models. Their attraction is their

youth and naivery. As Vivien Smith, of Vivien’s

Model Management, observed:

They want a brand-new face so people will ask,

“Who is this wonderful girl?” Another reason is

that young girls don't have lines on their faces

‘They'te like @ fresh canvas and che makeup artists

and photographers can create on them. (quoted by

Safe 1990: 26)

‘The youth of up-and-coming models contrasts

with the desire of the older top models to stay in

the business. Ten years used to be considered the

career span of a model. After that, they would

get married or try to enter a related field, such

as establishing their own agency, doing fashion

design, photography or consultation, joining

public relations firm, or acting (Hartman 1980:

63). Increasingly, models are extending their

modeling careers in other ways, through product

endorsements, personalized calendars, and mod-

cling for niche markets. The demand for older

models (in their thirties and forties) has also

grown, At the age of forty, Lisa Taylor was teem.

ployed by Calvin Klein, after she chided him for

employing young models to promote clothes

aimed at older women. The ploy was highly

successful, reestablishing Taylor's career, selling

Klein’s clothes, and prompting public pressure

to see more “role models of women when they're

women, not children” (Sherrill 1992: 88). In

other words, models are becoming career profes-

sionals.

Whereas models were at the beck and call of

agents who discovered them, clients and design-

ers who gave them work, stylists who decided on

their look, and photographers who constructed

their image, successful models have become

cough negotiators. This shift in the power rela-

tions in the industry has created tensions between

the old guard and the new “Cool Club” of super-

models. ‘They have become hard-nosed business-

women, demanding higher fees, and negotiating

the conditions of their contracts. As advertising

has become more competitive and international,

the supermodels have become “one of the few

reliable sales tools. Their beauty is a global ideal, as

desirable in Tokyo as in Prague, Manila or Buenos

Aires” (Rudolph 1991: 71). Equally, models are

often better known than the designers of the

clothes they wear, and attracting top models to

show the seasonal collections has become an in-

duscry priority. According to Eileen Ford of the

top New York agency, models are actively resist-

ing being treated as “this cute plaything or this

aithead” (Mode, September 1991: 72)

One of the most lucrative deals for models is

an exclusive contract with a cosmetics or fash-

ion designer or manufacturer, since it guarantees

an income and exclusive work. It brought fame

for Cindy Crawford (through Revlon), Paulina

Porizkova (through Estée Lauder), Isabella Ros-

sellini (Lancéme), and Claudia Schiffer (through

Guess?). The contracts for these deals are com-

prehensive, detailing the responsibilities of the

model to the employer. A contract between

American designer Calvin Klein and model Jose

Borain, to promote the perfume Obsession for

a million dollars over three years, specified the

following servi

all broadcast advertising, promotion and exploita-

tion (e.g., network, local, cable and closed circuit

television, AM and FM radio and cinema), print

advertising, promotion and exploitation (eg.,

princed hang-rags, labels, containers, packaging,

display materials sales brochures, covers, pictorial,

editorial, corporate reports and all other types of

promotional print material contained in the media

including magazines, newspapers, periodicals and

other publications ofall kinds), including but not

by way of limitation, fashion shows, runway mod-

cling, retail store crunk shows, individual mod-

cling and other areas of product promotion and

exploitation which are or may be considered to be

embraced within the concept of fashion modeling

(quoted by Faurschow 1987: 90)

For her part, Borain was required to maintain her

“weight, hairstyle and color and all other features

of ... physiognomy and physical appearance as

they are now or in such other form as CK may,

from time to time, reasonably request” (quoted

by Faurschou 1987: 90). The contract also speci-

fied that her personal lifestyle should:

be appropriate and most suitable to project an im-

age and persona that reflect the high standards and

dignity of the trademark “Calvin Klein” and chat

do not diminish, impair or in any manner detract

from the prestige and reputation of such trade-

mark, (quoted by Faurschou 1987: 91)

‘The contract could not be rerminated by Borain,

but Calvin Klein could do so should Borain be

disfigured, disabled, suffer illness or mental im-

pairment; should she “come into disrepute or

her public reputation [be] degraded or discred-

ited.” Ie could also be terminated on the death of

Borain or bankruptcy of Klein (Faurschou 1987:

91). Thus, the contract specified precise bodily

Features as well as the personal attributes of the

model deemed to reflect the qualities associated

with the product, Product endorsement has also

become an important sideline for Elle MacPher-

son. Launching her “Down-Underwear” line of

lingerie for Bendon, she described herself as “a

saleswoman’: “As a model I sell products. I'm a

very good saleswoman. Ir’s very nice to have been

SUPERMODELS AND SUPER BODIES | 285

a consumer, to be a salesperson and now to be a

creator and a ... realizateur” (Elle MacPherson,

quoted by Wyndham 1990: 23).

Changes within the modeling profession have

mitroted changes in the fashion industry as well

as reflecting new ideas of femininity and ideals of,

the female body. Above all, modeling has placed

a premium on particular constructions of beauty.

and female body shapes. Models currently

epitomize the ideal female persona in Western

culture, making top models highly desirable

companions:

If you're an egomaniacal celebrity who doesnt

consider che person on your arm to be a person

rather than an accessory, what do you go for? You

go for the accessory that is most sought after in

that world. If what you are looking for is a good=

looking woman, you naturally go looking in the

‘modeling catalog. (Mode Sepcember 1991: 74)

Modeling epitomizes techniques of wearing

the body by constructing the ideal technical

body, Through those techniques, the body is

produced according to criteria of beauty, gender,

fashion and movements. These change as codes

of prestigious imitation alter. The emphasis in

modeling is on self-formation through the body

to the exclusion of other attributes. As the model

Moncur said: “Ie an addiction, because you exist

through others’ eyes. When they stop looking at

you, there's nothing left” (quoted by Rudolph

1991; 75). Models are trapped in their images.

‘The increase in the use of male models suggests

that the equation of femininity with appearance

and bodily attributes has been a historical

moment; constructions of masculinity are now

undergoing a similar process of redefinition.

Techniques of masculinity are highlighting the

body as the site of discipline, labor and reconsti-

tution in the production of a social body that ar-

ticulates the self and fits its culeural milieu, and

where “the look” says ital.

286 | JENNIFER CRAIK

EDITORS’ NOTE

1. Earlier in the chapter from which this reading is

extracted, Craik gives a shore history of modeling,

“The use of models to display fashion designs com-

enced in the 1860s with haute couture. Initially

modeling was not considered co be a reputable

job. Gradually it was recognized as a profession

in England and America with the advent of mod-

ling agencies, although the pay was poor and

conditions were unstable. Most girls modeled for

a short time before “setsling down.” Finally in the

1950s, modelingbecameamajorindustry, develop-

ing into ewo branches: runway and photographic.

THE FASHION READER

Edited by

Linda Welters

and

Abby Lillethun

@BERG

Oxford * New York

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Too Pretty To Pay Bills - She Ra SevenDocument19 pagesToo Pretty To Pay Bills - She Ra SevenTamara Tanaskovic ZivkovicNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Wired For IntimacyDocument200 pagesWired For Intimacyaletmattheus100% (11)

- The Governor - S WifeDocument228 pagesThe Governor - S WifeBjc100% (3)

- D'Acci-Television, Representation and GenderDocument17 pagesD'Acci-Television, Representation and GenderAnonymous ec9pxmNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Kael Romano EbookDocument304 pagesKael Romano EbookAnastasha Grey100% (17)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- NOAA Solar Calculations DayDocument30 pagesNOAA Solar Calculations DayAnonymous ec9pxmNo ratings yet

- SAS 2014 ProceedingsDocument252 pagesSAS 2014 ProceedingsAnonymous ec9pxmNo ratings yet

- Entwistle - From Catwalk To CatalogDocument22 pagesEntwistle - From Catwalk To CatalogAnonymous ec9pxm100% (1)

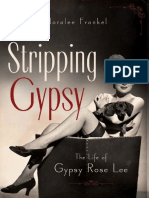

- Noralee Frankel Stripping Gypsy The Life of Gypsy Rose LeeDocument329 pagesNoralee Frankel Stripping Gypsy The Life of Gypsy Rose LeeKimon Fioretos50% (2)

- UK Home Office: PC42 2005Document36 pagesUK Home Office: PC42 2005UK_HomeOfficeNo ratings yet

- Unwanted But Consensual Sexting Among Young Adults Relations With Attachment and Sexual Motivations - 2014 - Computers in Human Behavior PDFDocument7 pagesUnwanted But Consensual Sexting Among Young Adults Relations With Attachment and Sexual Motivations - 2014 - Computers in Human Behavior PDFArielNo ratings yet

- General ZoologyDocument14 pagesGeneral ZoologyMatthew Gabales100% (1)

- Love MarriageDocument2 pagesLove MarriagejohnkingxNo ratings yet

- Void and Voidable MarriagesDocument9 pagesVoid and Voidable Marriagesella perezNo ratings yet

- PleasureDocument58 pagesPleasurefaradaiNo ratings yet

- A PRISMA Systematic Review of Adolescent Gender Dysphoria Literature: 1) EpidemiologyDocument38 pagesA PRISMA Systematic Review of Adolescent Gender Dysphoria Literature: 1) EpidemiologyAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- VOCABULARYDocument4 pagesVOCABULARYMunchKing1986No ratings yet

- On Lesbian and Gay - Queer Medieval Studies PDFDocument4 pagesOn Lesbian and Gay - Queer Medieval Studies PDFPilar Espitia DuránNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument10 pagesArticlePrachiNo ratings yet

- Unit-1 GENDER SENSITISATIONDocument7 pagesUnit-1 GENDER SENSITISATIONPiyushNo ratings yet

- Breeding: Dairy Hub Training Booklets TitlesDocument8 pagesBreeding: Dairy Hub Training Booklets TitlesZohaib PervaizNo ratings yet

- SC QPDocument13 pagesSC QPsharvan_creativeNo ratings yet

- Allina StoryDocument2 pagesAllina StoryJill BurcumNo ratings yet

- Modo de HerenciaDocument6 pagesModo de Herenciakamon328No ratings yet

- People vs. HangdaanDocument1 pagePeople vs. Hangdaangherold benitezNo ratings yet

- Forensic Interviewing of Children Who Have Been Sexually AbusedDocument5 pagesForensic Interviewing of Children Who Have Been Sexually AbusedJane GilgunNo ratings yet

- The Pornography of Meat (Book Review)Document3 pagesThe Pornography of Meat (Book Review)ValentínNo ratings yet

- Sexuality in The MediaDocument70 pagesSexuality in The MediaTee HopeNo ratings yet

- TexasDocument8 pagesTexasapi-280868990No ratings yet

- 04.polish and English MorphologyDocument4 pages04.polish and English MorphologyPiotrek MatczakNo ratings yet

- Women & Law SynopsisDocument4 pagesWomen & Law SynopsisRishi SehgalNo ratings yet

- Dreams Part 1Document10 pagesDreams Part 1nataliekuchikiNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument6 pagesCase StudyAvinash SinghNo ratings yet

- Gertrude - The Cry,' A Hamlet' Rewrite, at Atlantic Stage 2 - NYTimesDocument2 pagesGertrude - The Cry,' A Hamlet' Rewrite, at Atlantic Stage 2 - NYTimesfiliplatinovicNo ratings yet