Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Point of View

A Point of View

Uploaded by

api-3132644530 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

47 views6 pages1) The article discusses the themes of illusion and make-believe in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Great Gatsby. It argues Gatsby embodied the fantastical world of the 1920s that couldn't last.

2) Gatsby was a "perfect fake" who through sheer willpower made the wealthy believe in his imagined past and potential future. However, the prosperity of the 1920s was ultimately unsustainable, based more on debt and fraud than real wealth.

3) Like Gatsby and the characters in the novel, modern society still pursues an illusion of unrestrained future prosperity, wanting to believe in dreams despite knowing economic booms are temporary. We want to return to a

Original Description:

Original Title

a point of view

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1) The article discusses the themes of illusion and make-believe in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Great Gatsby. It argues Gatsby embodied the fantastical world of the 1920s that couldn't last.

2) Gatsby was a "perfect fake" who through sheer willpower made the wealthy believe in his imagined past and potential future. However, the prosperity of the 1920s was ultimately unsustainable, based more on debt and fraud than real wealth.

3) Like Gatsby and the characters in the novel, modern society still pursues an illusion of unrestrained future prosperity, wanting to believe in dreams despite knowing economic booms are temporary. We want to return to a

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

47 views6 pagesA Point of View

A Point of View

Uploaded by

api-3132644531) The article discusses the themes of illusion and make-believe in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Great Gatsby. It argues Gatsby embodied the fantastical world of the 1920s that couldn't last.

2) Gatsby was a "perfect fake" who through sheer willpower made the wealthy believe in his imagined past and potential future. However, the prosperity of the 1920s was ultimately unsustainable, based more on debt and fraud than real wealth.

3) Like Gatsby and the characters in the novel, modern society still pursues an illusion of unrestrained future prosperity, wanting to believe in dreams despite knowing economic booms are temporary. We want to return to a

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 6

A Point Of View: Gatsby and the

way we live now

Written By: BBC News

Not long before he died, a celebrated conjuror, whose

beautifully simple yet seemingly impossible tricks had earned

him the baffled admiration of his fellow magicians, was asked if

there was anything he still wanted. He replied, "I wish

somebody could fool me one more time."

The magician's confession came back into my mind when, a

few months ago, I re-read The Great Gatsby. Scott Fitzgerald's

novel - now in cinemas again - about a magnetically attractive

millionaire, can be read as a story of the Jazz Age and a

comment on the corruption of the American dream.

It's also a tangled, and finally tragic, love story. Using the

traumas of the "Lost Generation" that emerged disillusioned

from World War I, Fitzgerald distils a picture of how American

hopes of making a new start in history were derailed by a

culture whose energy was spun off from crime and fraud.

Yet I believe the unique quality of the book lies in its exploration

of a more universal theme. A form of make-believe is the basis

of society, and periods of extreme unreality like the Roaring

Twenties have recurred throughout history.

When reality breaks in, it's an interlude between different

versions of make-believe. If Gatsby's story resonates so

strongly with us as the new film of the book suggests, it's

because we find ourselves in just such an interlude at the

present time.

The most obvious fact about Gatsby is that everyone knew he

was a fake. While his friend Nick Carraway, who tells the story,

wanted always to give Gatsby the benefit of the doubt, an aura

of dissimulation surrounded the young tycoon from the start.

According to Carraway, Jay Gatsby - the more glamorous

name adopted by James Gatz at the age of 17 - "sprang from

his Platonic conception of himself". Gatz's parents were poor

farming people and he'd never really accepted them as his

family.

Like many before him and since, Gatsby was a self-invented

personality. Where he differed from other self-invented figures

was that the identity he invented for himself was a perfect

embodiment of the fantastic world around him.

"A universe of ineffable gaudiness spun itself out in his brain,"

Carraway notes - a universe that encompassed not just the

lavish parties that Gatsby laid on, but a multitude of glittering

possibilities far removed from the bootlegging and gangsterism

that were the true source of his wealth.

Gatsby yearned to make these squalid realities unreal, and so

establish as an accepted fact the image he had created of

himself. His wealthy friends knew he was a fraud and were

drawn to him for that very reason. Entranced by what Carraway

described as Gatsby's "extraordinary gift for hope", they too

wanted to make reality unreal.

If everyone knew he was a fake and still believed in him,

Gatsby must have been a rather special kind of fake.

When you study the history of forgery in the arts, you'll find that

what distinguishes the forged work from the genuine article

isn't the skill with which the original has been copied. Some

fake paintings are so good that they contain the artist's

distinctive defects.

Displaying these imperfections, these are the perfect fakes.

There's nothing in a fake of this kind that distinguishes it from a

painting by the artist himself. Yet the fake is still a fake, since

the story of how it was made is false. What makes fake art is

not any features of the art itself but the history of its production.

The wealthy people that flocked around Gatsby colluded with

him in his fakery because, like him, they wanted to forget how

their wealth had been made.

Fitzgerald's Jazz Age was a time when the borderlines

between the fortunes of the elite and the spoils of organized

crime were blurred and shifting. Prohibition helped create some

of the great figures of the time and later.

It's been claimed that the businessman and American

ambassador to Britain Joseph P Kennedy used wealth he

amassed from bootlegging to fund the political careers of his

sons John and Robert Kennedy. The legitimate part of his

fortune came from investing in Hollywood films - one of the

mass media that together with radio shaped America in the

1920s.

Easy money flowed from artificially low interest rates

engineered by the Federal Reserve Bank in order to lift the US

out of recession at the start of the decade. Powered by

reckless borrowing and shady practices, the soaring stock

market seemed to defy gravity until it crashed to earth in 1929.

Published in 1925, Fitzgerald's novel is astonishingly prescient

in its insight into the shaky prosperity that ended with the

crash. Some of the wealth that was created during the period

was real enough.

The 20s were the time when cars spread to the wider

population, new roads allowed cities to expand into suburbs

and electrification transformed everyday life. But much of the

prosperity of the period was insubstantial, and when the crash

came everybody was affected.

This wasn't only because the boom rested on debt that couldn't

be repaid. Much of the wealth of the time couldn't survive any

clear vision of how it was produced. In these circumstances,

Gatsby was the perfect fake.

There was no way the boom could go on indefinitely. Perhaps,

at some level, the wealthy elites that Fitzgerald describes knew

the boom had to end. If so, it was a fact they couldn't face.

Hence the magnetic appeal of a figure like Gatsby, whose

power of self-invention seemed able to prevail over any

underlying reality.

Fitzgerald didn't write to teach any moral lesson, and there's

none to be gleaned from The Great Gatsby.

Instead the story points to an unalterable fact. Human beings

live by suggestion, not calculation. Societies and economies

don't change like machines that function according to known

laws. They're more like dreams, which come and go for

reasons the dreamer can't perceive. Over the course of time,

as in the era that Fitzgerald portrays, the world that has been

created by the dream turns out to be an illusion.

So, too, are the figures that inhabit that world. Gatsby himself

has become a phantom by willfully pursuing an impossible

vision - trying to renew his relationship with the woman he

loved, and the short-lived intensity that existed in an

unrepeatable past.

Thinking of Gatsby near the end of the book, Carraway

expresses his view of the man and his world: "A new world,

material without being real, where poor ghosts, breathing

dreams like air, drifted fortuitously about"

Carraway admired Gatsby, even loved him, for his unyielding

loyalty to a vision of the unlimited possibilities of the future. At

the same time, Carraway realized that Gatsby was a flawed

and fated character who was bound unbreakably to the past.

It may be Gatsby's invincible attachment to illusion that

explains our current fascination with him and his world. Just as

in the Roaring Twenties, we've lived through a boom that was

mostly based on make-believe - easy money, inflated assets

and financial skulduggery.

The boom has ended, and no-one knows what will follow the

current hiatus. Yet it's clear we've not given up make-believe.

We want nothing more than to revive the fake prosperity that

preceded the crash. Just like Gatsby, we want to return to a

world that was conjured into being from dreams.

As Fitzgerald's narrator puts in the famous last lines of the

book:

"Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future

that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then,

but that's no matter - tomorrow we will run faster,

stretch out our arms further And one fine morning "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back

ceaselessly into the past."

We're possessed by Gatsby's vision of an unbounded future,

even though we know it to be a fantasy. Sooner or later, one

way or another, we'll find again the world of illusion we're

looking for. Like the old magician, we can't help wanting to be

fooled one more time.

You might also like

- The Great Gatsby Research PaperDocument5 pagesThe Great Gatsby Research PaperHayden Casey0% (1)

- The Great Gatsby Themes and Historical ContextDocument5 pagesThe Great Gatsby Themes and Historical ContextEdward Low100% (5)

- Floridi. Por Una Filosofía de La Información.Document12 pagesFloridi. Por Una Filosofía de La Información.Nadia_Karina_C_9395No ratings yet

- Kez PaperDocument3 pagesKez Paperapi-314555596No ratings yet

- The Great Gatsby and The American DreamDocument2 pagesThe Great Gatsby and The American DreamNicoleta Cristina SuciuNo ratings yet

- Gatsby: Sunday, June 02, 2013 11:50 PMDocument2 pagesGatsby: Sunday, June 02, 2013 11:50 PMTheng RogerNo ratings yet

- Gatsby Portrays This Shift As A Symbol of The American Dream's Corruption. It's No Longer A VisionDocument3 pagesGatsby Portrays This Shift As A Symbol of The American Dream's Corruption. It's No Longer A VisionnatalieNo ratings yet

- Selma Slezovic SIR2 Great GatsbyDocument13 pagesSelma Slezovic SIR2 Great GatsbySelma Slezovic MehovicNo ratings yet

- The Observer - Gatsby Is BackDocument2 pagesThe Observer - Gatsby Is BackAdjeanNo ratings yet

- The Great Gatsby The American Dream ThesisDocument8 pagesThe Great Gatsby The American Dream ThesisNathan Mathis100% (2)

- The Great Gatsby Francis Scott Fitzgerald Is Considered One of The Greatest American Writers. He IsDocument2 pagesThe Great Gatsby Francis Scott Fitzgerald Is Considered One of The Greatest American Writers. He IsMarioara CiobanuNo ratings yet

- The Great Gatsby EssayDocument5 pagesThe Great Gatsby EssayJoshua BishunNo ratings yet

- The Great GatsbyDocument7 pagesThe Great GatsbyScarlat TeodoraNo ratings yet

- American Dream As The Major Theme of The Great GatsbyDocument9 pagesAmerican Dream As The Major Theme of The Great GatsbyCrazy KhanNo ratings yet

- The Great Gatsby, A Doll's House and The Reluctant Fundamentalist AnalysisDocument3 pagesThe Great Gatsby, A Doll's House and The Reluctant Fundamentalist Analysissofia0% (1)

- Great Gatsby Thesis Statement American DreamDocument4 pagesGreat Gatsby Thesis Statement American Dreamdwtnpjyv100% (2)

- Gatsby American Dream ThesisDocument5 pagesGatsby American Dream Thesisaimeebrowngilbert100% (2)

- HL - Essay - Great - Gatsby - Final FinalDocument9 pagesHL - Essay - Great - Gatsby - Final Finalmaria.ficek07No ratings yet

- Literature IADocument4 pagesLiterature IANaomi Huggins100% (10)

- The Great Gatsby Thesis Statement American DreamDocument8 pagesThe Great Gatsby Thesis Statement American DreamBuyCollegePapersClearwater100% (2)

- TheamericancontradictionDocument4 pagesTheamericancontradictionapi-285296302No ratings yet

- Gatsby Thesis American DreamDocument6 pagesGatsby Thesis American Dreambk2dn708100% (1)

- ReportDocument6 pagesReportapi-673170560No ratings yet

- The Great Gatsby Is One of The Finest Examples of Literature in America andDocument3 pagesThe Great Gatsby Is One of The Finest Examples of Literature in America andapi-267298210No ratings yet

- Scarlet & GatsbyDocument32 pagesScarlet & GatsbyNadelyn BatoNo ratings yet

- Maxwell E. Perkins On The Vagueness of The Character of GatsbyDocument4 pagesMaxwell E. Perkins On The Vagueness of The Character of GatsbyandreidmannnNo ratings yet

- Essay - The Great GatsbyDocument7 pagesEssay - The Great Gatsbyapi-672762891No ratings yet

- How Does Fitzgerald Portray The Corruption of The American Dream in The Great GatsbyDocument2 pagesHow Does Fitzgerald Portray The Corruption of The American Dream in The Great GatsbyTony KimNo ratings yet

- Theme AnalysisDocument2 pagesTheme AnalysisÖzlem Demiröz AkgünNo ratings yet

- North American Literature 1 - Short PaperDocument5 pagesNorth American Literature 1 - Short PaperAreikoNo ratings yet

- Writing A Research Paper On The Great GatsbyDocument5 pagesWriting A Research Paper On The Great Gatsbyyelbsyvkg100% (3)

- The Great GatsbyDocument2 pagesThe Great Gatsbyjiminp0127No ratings yet

- Tarea Reseña de Un Libro en InglesDocument1 pageTarea Reseña de Un Libro en InglesOmar Ambrosio JuarezNo ratings yet

- Madeline Hopwood - Final DocumentDocument10 pagesMadeline Hopwood - Final Documentapi-692338690No ratings yet

- Jelica Jane Novel ReviewDocument10 pagesJelica Jane Novel ReviewBelinda MorataNo ratings yet

- The Great Gatsby - Key FactsDocument8 pagesThe Great Gatsby - Key Factssilvina bottoNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewDocument1 pageBook Reviewgenazn88No ratings yet

- Francis Scott FitzgeraldDocument3 pagesFrancis Scott FitzgeraldRoxana ȘtefanNo ratings yet

- Themes and ConstructionDocument4 pagesThemes and Constructiongiledidana123No ratings yet

- Aqa 7716 7717 Tragedy Great GatsbyDocument5 pagesAqa 7716 7717 Tragedy Great GatsbyAnh TrầnNo ratings yet

- 11E4 - REVIEW BOOK - Thành Nhân 93Document2 pages11E4 - REVIEW BOOK - Thành Nhân 93Yu ZhouNo ratings yet

- Essay YayDocument6 pagesEssay YayAdrian GalerNo ratings yet

- The Great Gatsby Students' EditionDocument22 pagesThe Great Gatsby Students' EditionSouad El-souqiNo ratings yet

- The Decline of The American Dream in The 1920sDocument3 pagesThe Decline of The American Dream in The 1920smostarjelicaNo ratings yet

- GatsbyDocument2 pagesGatsbyChandoNo ratings yet

- Great Gatsby AnalysisDocument10 pagesGreat Gatsby AnalysisHamna sirajNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On The Great Gatsby TopicsDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On The Great Gatsby Topicsuzypvhhkf100% (3)

- Research Paper On The Great Gatsby American DreamDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On The Great Gatsby American DreamyscgudvndNo ratings yet

- Gastby Essay Harley JeanDocument4 pagesGastby Essay Harley JeanHarley JeanNo ratings yet

- The Great GatsbyDocument3 pagesThe Great Gatsbyashutoshkumar110920No ratings yet

- Research Paper On Great Gatsby SymbolismDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Great Gatsby Symbolismafeawldza100% (1)

- The Falling Off The Great Gatsby's American DreamDocument5 pagesThe Falling Off The Great Gatsby's American DreamjcthoreauNo ratings yet

- TGG EssayDocument2 pagesTGG Essayaryananvekar646No ratings yet

- American Dream Thesis Great GatsbyDocument5 pagesAmerican Dream Thesis Great GatsbyPayToWriteAPaperLubbock100% (2)

- Summary and Review of the Great GatsbyDocument1 pageSummary and Review of the Great GatsbykidusNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statements For The Great Gatsby American DreamDocument4 pagesThesis Statements For The Great Gatsby American DreamMaria Perkins67% (3)

- Great Gatsby American Dream Thesis StatementsDocument7 pagesGreat Gatsby American Dream Thesis Statementsjqcoplhld100% (1)

- Copia de LIMPIO (Recuperado Automáticamente)Document13 pagesCopia de LIMPIO (Recuperado Automáticamente)Miry García GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Idealism in The Great GatsbyDocument16 pagesIdealism in The Great Gatsbychia simNo ratings yet

- Eva WU The Great Gatsbt TranscriptDocument2 pagesEva WU The Great Gatsbt TranscriptEvaNo ratings yet

- ECG-Based Biometric Schemes For Healthcare: A Systematic ReviewDocument23 pagesECG-Based Biometric Schemes For Healthcare: A Systematic ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Bharat Heavy Electricals LimitedDocument4 pagesBharat Heavy Electricals LimitedkmbkrisNo ratings yet

- Fluency ReflectionDocument7 pagesFluency Reflectionapi-316375440No ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Towards The Retail Footwear Industry: A Project Report OnDocument27 pagesConsumer Behaviour Towards The Retail Footwear Industry: A Project Report Onangelamonteiro1234No ratings yet

- Clinical Laboratory of San Bernardino, IncDocument40 pagesClinical Laboratory of San Bernardino, Inckharberson1613No ratings yet

- Recognition and Extinction of StatesDocument4 pagesRecognition and Extinction of StatesCristy C. BangayanNo ratings yet

- Ernst Gombrich - Power and Glory I (Ch. 21)Document11 pagesErnst Gombrich - Power and Glory I (Ch. 21)Kraftfeld100% (1)

- Charge PointDocument8 pagesCharge PointluishernandezlaraNo ratings yet

- 2046 - Decorative Synthetic Bonded Laminated SheetsDocument53 pages2046 - Decorative Synthetic Bonded Laminated SheetsKaushik SenguptaNo ratings yet

- ESS Questionnaire StaffDocument2 pagesESS Questionnaire StaffSarita LandaNo ratings yet

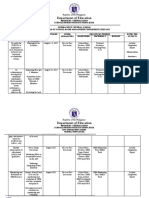

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesRussel RapisoraNo ratings yet

- NCM - 103Document5 pagesNCM - 103Delma SimbahanNo ratings yet

- MATH7 - PPT - Q2 - W1 - Day1 - Measuring QuantitiesDocument28 pagesMATH7 - PPT - Q2 - W1 - Day1 - Measuring QuantitiesEveNo ratings yet

- Integration of New Literacies in The CurriculumDocument10 pagesIntegration of New Literacies in The CurriculumMariel Mae PolancosNo ratings yet

- Integrated Door Motor Controller User Manual: Shenyang Bluelight Automatic Technology Co., LTDDocument56 pagesIntegrated Door Motor Controller User Manual: Shenyang Bluelight Automatic Technology Co., LTDJulio Cesar GonzalezNo ratings yet

- CultureDocument9 pagesCultureAntony Duran TorresNo ratings yet

- 06 The Table of Shewbread Study 6Document4 pages06 The Table of Shewbread Study 6High Mountain StudioNo ratings yet

- Articulated Haulers / F Series Models: Description Part No. Qty First Service 250 H 500 H 1000 H 2000 H NotesDocument4 pagesArticulated Haulers / F Series Models: Description Part No. Qty First Service 250 H 500 H 1000 H 2000 H NotesHugo Alejandro Bello ParraNo ratings yet

- CPT & Suctioning Rle ExamDocument2 pagesCPT & Suctioning Rle ExamJojo JustoNo ratings yet

- Transform Techniques For Error Control Codes: R. E. BlahutDocument17 pagesTransform Techniques For Error Control Codes: R. E. BlahutFjolla AdemajNo ratings yet

- P PotassiumDocument12 pagesP PotassiumHeleneSmithNo ratings yet

- UGWT Lecture 1 To 6Document83 pagesUGWT Lecture 1 To 6Meesam AliNo ratings yet

- What I Need To Know? What I Need To Know?: Quarter 1Document16 pagesWhat I Need To Know? What I Need To Know?: Quarter 1Aileen gay PayunanNo ratings yet

- The Alexander Technique and Flute PlayingDocument7 pagesThe Alexander Technique and Flute PlayingCarlos Andres CarpizoNo ratings yet

- Ayamas Journal PDFDocument8 pagesAyamas Journal PDFRaajKumarNo ratings yet

- Eofy 1363807 202307141612Document6 pagesEofy 1363807 202307141612Jeffrey BoucherNo ratings yet

- State Centric Theories of International Relations Belong To The Past in Security StudiesDocument3 pagesState Centric Theories of International Relations Belong To The Past in Security StudiesshoufiiNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs Capsule For SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 - Part 2Document253 pagesCurrent Affairs Capsule For SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 - Part 2King SammyNo ratings yet

- The Multi-Crew Pilot Licence (MPL)Document28 pagesThe Multi-Crew Pilot Licence (MPL)Vivek ChaturvediNo ratings yet