Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gov't of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, No. CVA14-011 (Guam Mar. 17, 2016)

Gov't of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, No. CVA14-011 (Guam Mar. 17, 2016)

Uploaded by

RHTCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gov't of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, No. CVA14-011 (Guam Mar. 17, 2016)

Gov't of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, No. CVA14-011 (Guam Mar. 17, 2016)

Uploaded by

RHTCopyright:

Available Formats

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF GUAM

GOVERNMENT OF GUAM,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

162.40 SQUARE METERS OF LAND, more or less, situated in the

municipality of Agana and UNKNOWN OWNERS,

Defendants-Appellees,

ARTEMIO B. ILAGAN,

Defendant-Appellant,

ENGRACIA UNGACTA and FELIX F. UNGACTA,

Defendants-Appellees.

OPINION

Cite as: 2016 Guam 10

Supreme Court Case No.: CVA14-011

Superior Court Case No.: CV0863-81

Appeal from the Superior Court of Guam

Argued and submitted on July 2, 2015

Dededo, Guam

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Appearing for Defendant-Appellant:

Seth Forman, Esq.

Dooley Roberts & Fowler LLP

Orlean Pacific Plaza

865 S. Marine Corps Dr., Ste. 201

Tamuning, GU 96913

Appearing for Plaintiff-Appellee:

David J. Highsmith, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General

590 S. Marine Corps Dr., Ste. 706

Tamuning, GU 96913

Page 2 of 17

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 3 of 17

BEFORE: ALEXANDRO C. CASTRO, Presiding Justice Pro Tempore; JOHN A.

MANGLONA, Justice Pro Tempore; ALBERTO E. TOLENTINO, Justice Pro Tempore.1

PER CURIAM:

[1]

This case is on its second appeal after remand to the trial court in accordance with this

courts opinion in Government of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land More or Less, Situated

in the Municipality of Agana (162.40 Square Meters of Land I), 2011 Guam 17. On remand,

the trial court determined that just compensation at the time of Plaintiff-Appellee Government of

Guams (the Government) taking of Defendant-Appellant Artemio M. Ilagans2 property was

$45,000.00, which amount was less than what had been deposited by the Government at the time

of the taking. Ilagan appeals the trial courts determination concerning the rate of interest on the

deficiency and its decision to award Ilagan simple, rather than compound, interest.

[2]

For the reasons set forth below, we reverse.

I. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

[3]

The facts underlying the original trial court proceedings can be found in 162.40 Square

Meters of Land I, 2011 Guam 17; thus, only those facts which are relevant to the current appeal

will be recited.

[4]

On November 27, 1981, the Government issued a Declaration of Taking, condemning

162.40 square meters of land owned by Ilagan for the purpose of transferring said property to

All three full-time justices recused themselves from this matter. On July 9, 2014, pursuant to 7 GCA

6108(a) and the Rule of Necessity, United States v. Will, 449 U.S. 200, 213-17 (1980), Chief Justice Robert J. Torres

appointed the Honorable Alexandro C. Castro to serve as Presiding Justice Pro Tempore in this matter. Presiding

Justice Castro then appointed the Honorable John A. Manglona and the Honorable Alberto E. Tolentino to serve as

Justices Pro Tempore.

2

On June 17, 2015, counsel for Defendant-Appellant Artemio M. Ilagan filed a Motion for Substitution of

Party, informing the court that Mr. Ilagan passed away on February 9, 2015, and moving that Artemio B. Ilagan, in

his capacity as Special Administrator for the Estate of Artemio M. Ilagan, be substituted as Defendant-Appellant in

this action. This court granted the motion for substitution on June 30, 2015. For purposes of clarity, the references

in this opinion to Ilagan are to the decedent, Artemio M. Ilagan.

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 4 of 17

Ilagans neighbors, Defendants-Appellees Felix F. Ungacta and Engracia Ungacta (the

Ungactas), pursuant to the Governments post-World War II Agana Plan, a plan for

condemnation and redistribution of land in the village of Agana. Record on Appeal (RA), tab

2 at 1-2 (Decl. of Taking, Dec. 1, 1981). The Government deposited in the Court Registry the

amount of $9,744.00 as just compensation to Ilagan for the taking.

[5]

The Government filed a Complaint in Condemnation on December 1, 1981. Ilagan

contested the condemnation on grounds that the taking was not for a public purpose.

[6]

The matter went to trial in 2009. In 2010, the trial court entered judgment in favor of

Ilagan, holding that the taking was not part of the Agana Plan and, therefore, was not condemned

pursuant to a valid public purpose. The Ungactas appealed.

[7]

This court reversed the judgment, holding that there was sufficient evidence that Ilagans

property was taken pursuant to the Agana Plan and for a valid public purpose. The matter was

remanded to the trial court to determine the issue of whether just compensation was paid to

Ilagan.

[8]

On remand, the trial court ruled that just compensation at the time of the taking was

$45,000.00, i.e., $35,256.00 more than the $9,744.00 that was deposited in the Court Registry at

the time of the taking. As to the interest owed to Ilagan on this difference, the court awarded

him simple interest at the rate of 6% per year from the date of the Declaration of Taking. Ilagan

timely appealed.

II. JURISDICTION

[9]

This court has jurisdiction over an appeal from a final judgment of the Superior Court of

Guam. 48 U.S.C.A. 1424-1(a)(2) (Westlaw through Pub. L. 114-114 (2015)); 7 GCA 3107,

3108(a) (2005).

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 5 of 17

III. STANDARD OF REVIEW

[10]

Although a trial courts award of interest, including its decision to award simple, rather

than compound interest, is generally reviewed for an abuse of discretion, Guam United

Warehouse Corp. v. DeWitt Transp. Servs. of Guam, Inc., 2003 Guam 20 36 (citing Sumitomo

Constr., Co. v. Govt of Guam, 2001 Guam 23 7), any statutory interpretation or legal analysis

is reviewed de novo, see Guam Top Builders, Inc. v. Tanota Partners, 2012 Guam 12 63

(citations omitted). Thus, the issue of whether interest on a condemnation award can be subject

to a statutory cap, being a question of law, warrants de novo review.

IV. ANALYSIS

[11]

The final clause of the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitutionthe Takings

Clauseprovides: [N]or shall private property be taken for public use, without just

compensation. U.S. Const. amend. V. This right has been extended to Guam by way of the

Organic Act of Guam. 48 U.S.C.A. 1421b(f) (Westlaw current through Pub. L. 114-114

(2015)) (Private property shall not be taken for public use without just compensation.); id.

1421b(u) (extending certain amendments to the United States Constitution to Guam, including

the Fifth Amendment). The Takings Clause is a limitation on governmental power, and is

intended to prevent the government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens,

which in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole. Gutierrez v. Guam

Power Auth., 2013 Guam 1 32 (quoting Cepeda v. Govt of Guam, 2005 Guam 11 20). Thus,

while the government is not prohibited from the taking of private property for a public purpose,

the Fifth Amendment guarantees just compensation to the property owner for such a taking. Id.

32, 47 (citations omitted).

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

[12]

Page 6 of 17

Ilagan argues that the trial courts determination concerning the rate of interest on his just

compensation award and its decision to award him simple, rather than compound, interest

deprive him of his Fifth Amendment right to just compensation. See Appellants Br. at 17-18

(May 15, 2014). We address each argument in turn.

A. Whether the Rate of Interest on a Just Compensation Award Can be Limited by Statute

[13]

The U.S. Supreme Court has defined just compensation as the full and perfect

equivalent in money of the property taken. The owner is to be put in as good [a] position

pecuniarily as he would have occupied if his property had not been taken. Gutierrez, 2013

Guam 1 47 (alteration in original) (quoting United States v. Miller, 317 U.S. 369, 373 (1943)

(citing Commr of Transp. v. Rocky Mountain, LLC, 894 A.2d 259, 281 (Conn. 2006)). [I]f

disbursement of the award is delayed, the owner is entitled to interest thereon sufficient to ensure

that he is placed in as good a position pecuniarily as he would have occupied if the payment had

coincided with the appropriation. Kirby Forest Indus., Inc. v. United States, 467 U.S. 1, 10

(1984) (citing Phelps v. United States, 274 U.S. 341, 344 (1927); Seaboard Air Line Ry. Co. v.

United States, 261 U.S. 299, 306 (1923)); see also United States v. Blankinship, 543 F.2d 1272,

1275 (9th Cir. 1976) ([I]n order that the owner shall not suffer loss and shall have the just

compensation to which he is entitled[,] . . . an extra amount must be paid when the taking

precedes the payment of compensation; [i]nterest at a proper rate is a good measure. (third

alteration in original) (quoting Seaboard, 261 U.S. at 306)).

[14]

To that end, 21 GCA 15107 provides, in pertinent part:

Upon the filing of [a] declaration of taking and of the deposit in the court,

to the use of the persons entitled thereto, of the amount of the estimated

compensation stated in said declaration, title to the said lands in fee simple

absolute, or such estate or interest therein as is specified in said declaration, shall

vest in the government of Guam, and said lands shall be deemed to be condemned

and taken for the use of the government of Guam, and the right to just

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 7 of 17

compensation for the same shall vest in the persons entitled thereto; and said

compensation shall be ascertained and awarded in said proceeding and established

by judgment therein, and the said judgment shall include, as part of the just

compensation awarded, interest at the rate of six percent (6%) per annum on the

amount finally awarded as the value of the property as of the date of taking, from

said date to the date of payment; but interest shall not be allowed on so much

thereof as shall have been paid into the court. No sum so paid into the court shall

be charged with commissions or poundage.

21 GCA 15107 (2005) (emphasis added). At trial, Ilagans appraiser, W. Nicholas Captain,

provided the court with a report on what he deemed the rate of interest required to justly

compensate Ilagan for the delay in payment. Using long-term U.S. Treasury ratesspecifically,

the 20- and 30-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rateon an annual basis, as well as compound

interest, Captain determined that from the time of taking through January 1, 2008, the

$45,000.00 just compensation award would have grown to $302,827.00.2 See Def.s Ex. I-N

(Consulting Report, Dec. 29, 2008). The trial court, however, relying on 21 GCA 15107,

awarded Ilagan simple interest at the rate of 6% per annum on the deficiency. RA, tab 254 at 4

(Dec. & Order, Mar. 4, 2014).

[15]

Ilagan argues that [t]he Government cannot arbitrarily limit the rate of interest for just

compensation purposes by statute. Appellants Br. at 15. Citing to Ninth Circuit precedent,

Ilagan contends that any statutory rate of interest in a condemnation statute sets only a floor on

interest and not a ceiling. Id. at 20 (citing Schneider v. County of San Diego, 285 F.3d 784, 793

(9th Cir. 2002); United States v. 50.50 Acres of Land, 931 F.2d 1349, 1355 (9th Cir. 1991);

Blankinship, 543 F.2d at 1276.

He further argues that [t]he proper rate of interest in a

condemnation action is a rate at which a reasonably prudent person would receive if investing so

as to produce a reasonable return while maintaining safety of principal. Id. (citing Schneider,

Using the same methodology, Captain also determined that the original deposit of $9,744.00 would have

grown to $65,575.00 by January 1, 2008. See Def.s Ex. I-N (Consulting Report, Dec. 29, 2008).

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 8 of 17

285 F.3d at 792; 50.50 Acres, 931 F.2d at 1355; Redevelopment Agency of the City of Burbank v.

Gilmore, 700 P.2d 794, 805-06 (Cal. 1985)).

[16]

In response, the Government argues that because a Guam statute, 21 GCA 15107,

governs this issue:

Mr. Ilagan must establish that there is a constitutional infirmity of some kind with

either the statute itself or with the trial courts application of it in order to prevail.

This is a burden he cannot meet. The Organic Act and the Constitution do not

require an upward departure from the statutory interest rate of six percent.

Appellees Br. at 4 (June 5, 2014) (citing 48 U.S.C.A. 1421b(u); U.S. Const. amend. V).

According to the Government, unless the owner can demonstrate that a higher rate is

constitutionally required, the statutory interest rate should generally be used. Id. at 8 (citing

Textainer Mgmt. Ltd. v. United States, 99 Fed. Cl. 211 (Fed. Cl. 2011); Vaizburd v. United

States, 67 Fed. Cl. 499 (Fed. Cl. 2005)). Quoting an unpublished Ninth Circuit case, the

Government maintains that [a] court must consider an alternative interest rate only if

competent evidence is presented supporting another rate of interest as being more appropriate.

Id. (quoting Vacation Vill., Inc. v. Clark Cnty., Nev., 244 Fed. Appx. 785, 789 (9th Cir. 2007)).

[17]

In setting interest at the rate of 6% per annum, the trial court took note of federal

precedent holding that under the Federal Declaration of Taking Act, the 6% interest rate on a just

compensation award is a floor rather than a ceiling. RA, tab 254 at 4 (Dec. & Order) (citing

Blankinship, 543 F.2d at 1276). However, the trial court then cited two U.S. Supreme Court

cases for the proposition that the local interest rate is a fair and reasonable method of

ascertaining interest in condemnation proceedings. Id. (citing Seaboard, 261 U.S. at 305;

United States v. Rogers, 255 U.S. 163, 169 (1921)). The court concluded, Considering that the

language of 21 G.C.A. 15107 . . . prescribes a rate of six percent, the Court discerns no

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 9 of 17

statutory authority for imposing . . . a higher rate of interest on the just compensation due in this

case. Id.

[18]

The trial courts reasoning is flawed in two respects. First, the court failed to note the

significant factual distinctions among Seaboard, Rogers, and the instant case.

While in

Seaboard and Rogers the Court found the application of a statutory interest rate to be proper,

neither of those cases involved a question regarding the sufficiency of the statutory rate of

interest. Instead, both appeals, from the early 1920s, were brought by the United States on the

issue of whether interest should have been awarded against the government in the first place.

See Seaboard, 261 U.S. at 303; Rogers, 255 U.S. at 168. The Court determined in both cases

that interest was necessary in order to provide just compensation to the owners of the condemned

properties; accordingly, the Court affirmed the lower courts application of the local statutory

interest rate in each case. See Seaboard, 261 U.S. at 305-06; Rogers, 255 U.S. at 169-70.

Neither case involved the specific question of whether the applicable statutory rate of interest

satisfied the requirement of just compensation.

[19]

Second, the trial court, in denying Ilagan a greater rate of interest, improperly relied on

the fact that no statutory authority exists allowing interest at a rate higher than 6% as provided by

21 GCA 15107. Just compensation is provided for by the Constitution and the right to it

cannot be taken away by statute. Seaboard, 261 U.S. at 304 (citing Monongahela Navigation

Co. v. United States, 148 U.S. 312, 327 (1893)).

By setting the interest rate for just

compensation awards at 6% per annum, the Guam Legislature seems to have assumed the right

to determine what shall be the measure of compensation in eminent domain cases. But this is a

judicial, and not a legislative, question. Monongahela, 148 U.S. at 327. As put by the Supreme

Court in Monongahela,

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 10 of 17

The legislature may determine what private property is needed for public

purposes; that is a question of a political and legislative character. But when the

taking has been ordered, then the question of compensation is judicial. It does not

rest with the public, taking the property, through congress or the legislature, its

representative, to say what compensation shall be paid, or even what shall be the

rule of compensation. The constitution has declared that just compensation shall

be paid, and the ascertainment of that is a judicial inquiry.

Id. Courts therefore are not bound by statutory interest rates in the condemnation context.

Although the legislature can suggest possible rates, the ultimate determination of the rate of

interest to be applied in a condemnation proceeding rests with the trial court.

State by

Humphrey v. Baillon Co., 480 N.W.2d 673, 676 (Minn. Ct. App. 1992); see also Lea Co. v. N.C.

Bd. of Transp., 345 S.E.2d 355, 358-59 (N.C. 1986) (Since the ascertainment of just

compensation is a judicial function and compensation for delay in payment is a part of just

compensation, determining the amount of additional compensation for delay in payment is also a

judicial function. (citations omitted)).

[20]

While courts are in general agreement that they are not bound by statutory interest rates

in condemnation proceedings, [s]everal jurisdictions have applied an interest rate set by statute

if that interest rate satisfies the requirement that just compensation be paid for a taking. Lea

Co., 345 S.E.2d at 359 (emphasis added) (citing Miller v. United States, 620 F.2d 812, 837 (Ct.

Cl. 1980); In re City of New York, 449 N.E.2d 399, 401 (N.Y. 1983)). Some jurisdictions have

held that the statutory rate is presumptively reasonable, allowing the landowner to rebut the

rates reasonableness. E.g., Liberty Square Dev. Trust v. City of Worcester, 808 N.E.2d 245,

251-52 (Mass. 2004) ([A]ny interest rate set by statute enjoys a rebuttable presumption that it is

a reasonable rate that would satisfy constitutional requirements.

A claimant seeking

compensation above the statutory rate may overcome that presumption by showing that the

statutory rate is so low that it fails to meet the constitutional standard of reasonableness.

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 11 of 17

(citations omitted)); State by Humphrey v. Jim Lupient Oldsmobile Co., 509 N.W.2d 361, 364

(Minn. 1993) ([T]he trial court should presume that the statutory rate is reasonable and,

therefore, meets the requirements of just compensation and should order judgment at that rate

unless the condemnee rebuts this presumption and affirmatively shows that another rate is

reasonable and affords just compensation.); In re City of New York, 449 N.E.2d at 401 (The

Legislature may fix a fair or prima facie measure of the proper interest rate in the first instance, .

. . but while that legislatively fixed rate is presumptively reasonable, it is not determinative of the

issue. The claimant may introduce relevant evidence of prevailing market rates to rebut the

statutory presumption of reasonableness and demonstrate that some higher rate must be paid to

afford him just compensation.). Contra Leverty & Hurley Co. v. Commr of Transp., 471 A.2d

958, 960 n.4 (Conn. 1984) (declining to accord presumption status to statutory interest rate).

[21]

Other jurisdictions have held that a trial court must make an independent assessment of

the rate of interest necessary to provide the landowner with just compensation, rather than simply

rely upon statutory rates. In Blankinship,3 the Ninth Circuit directed district courts to use a factspecific approach to determine if the statutory rate was proper and reasonable, or if the Fifth

Amendment required a higher rate of interest. 50.50 Acres of Land, 931 F.2d at 1355 (quoting

Blankinship, 543 F.2d at 1274). Under the Ninth Circuit approach:

the court must determine if the statutory formula is constitutionally inadequate

given the factual circumstances of the case. The court should receive evidence

from each side and consider a variety of investment measures. If the court finds

the statutory formula to be inadequate, it must then determine the appropriate rate

to be used.

In Blankinship, the court held that the 6 percent figure employed by Congress in the Declaration of

Taking Act cannot be viewed as a ceiling on the rate of interest allowable . . . . It will, of course, operate as a floor.

No lesser rate than 6 percent is consistent with the intent of Congress; a rate no greater than 6 percent in some

instances will contravene the Fifth Amendment. 543 F.2d at 1276.

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Id. (citing Blankinship, 543 F.2d at 1274).

Page 12 of 17

The standard to be used in determining the

appropriate rate of interest is to fix interest . . . at the rate a reasonably prudent person investing

funds so as to produce a reasonable return while maintaining safety of principal would receive.

Id. (quoting United States v. 429.59 Acres of Land, 612 F.2d 459, 465 (9th Cir. 1980)); see also

Jim Lupient Oldsmobile Co., 509 N.W.2d at 363 (We believe that a reasonable rate is what a

reasonable and prudent investor would earn while investing so as to maximize the rate of return

over the relevant period of time, yet guarantee safety of principal.); State by Spannaus v.

Carney, 309 N.W.2d 775, 776 (Minn. 1981) (The landowner is entitled to that return which

would have been available if the landowner has been timely paid and had made reasonable and

prudent investments.).

[22]

We are persuaded by the rebuttable presumption approach and hold that the statutory

rate set by 21 GCA 15107 is entitled to a presumption of reasonableness. A landowner seeking

compensation above the statutory rate may rebut the presumption by showing that the rate fails

to meet the constitutional standard of just compensation. Thus, the court is not bound by the

statutory rate and must consider evidence offered to rebut the presumption of reasonableness.

Furthermore, we hold that the statutory rate operates as a floor; while the court is not bound by

the rate, it may only deviate upward, not downward. See Blankinship, 543 F.3d at 1276.

[23]

Here, the trial courts Decision and Order made no mention of the evidence presented by

Ilagan in support of his request for a rate above the statutory rate of 6%. Instead, it appears the

court believed it was bound by 21 GCA 15107, noting that the Court discerns no statutory

authority for imposing . . . a higher rate of interest . . . . RA, tab 254 at 4 (Dec. & Order). This

strict application of the statutory interest rate without a determination of whether the rate actually

provides just compensation to Ilagan is inconsistent with the overwhelming precedent that the

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

proper rate of interest is a judicial determination.

Page 13 of 17

Under either the presumption of

reasonableness approach or the independent assessment approach, Ilagan was entitled to not

only put forth evidence in support of his argument that an interest rate beyond that provided by

statute is required in order to provide him just compensation, but to have that evidence assessed

by the trial court in determining the proper rate. The trial courts failure to consider whether the

6% interest rate actually provided Ilagan just compensation constituted an abuse of discretion.

[24]

Because the trial court did not analyze the evidence presented by Ilagan and determine

whether he successfully rebutted the presumption of reasonableness attached to the statutory rate,

we must remand the matter to the Superior Court for determination of this issue in the first

instance. Because of the decades-long duration of this case over 34 years as well as the fact

that Mr. Ilagan passed away during the pendency of this appeal, we strongly urge the trial court

and the parties to reach finality of this case. In order to prevent unnecessary delay of the

proceedings below and to avoid giving the litigants a second bite at the apple, we instruct the

trial court to render its interest award on the basis of the evidence already in the record, allowing

new evidence of the applicable interest rates only for those dates for which evidence was not

already presented. Captains report provided the annual Treasury rates from January 1982 to

January 2008. Thus, the trial court should consider new evidence of the applicable interest rates

since January 2008 and through payment of the just compensation award. Moreover, as we hold

that the statutory rate operates as a floor, in rendering its interest award, the trial court may

deviate above, but not below, 6%.

[25]

We now turn to the issue of whether the interest rate should be simple or compounded.

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 14 of 17

B. Whether Just Compensation Requires the Award of Compound, Rather than Simple,

Interest

[26]

At trial, Ilagan argued that he was entitled to compound interest on the deficiency award

(i.e., the difference between the value of the property at the time of the taking, $45,000.00, and

the Governments original deposit for the taking, $9,744.00), as calculated by Captain in his

consulting report. See Def.s Ex. I-N (Consulting Report). The trial court denied Ilagans

request for compound interest, and instead awarded him simple interest at the rate of 6% as

provided under 21 GCA 15107. On appeal, Ilagan argues that [c]ompounding of interest is

necessary to satisfy the constitutional mandate of just compensation. Appellants Br. at 22. He

reasons that if the full value of just compensation had been deposited with the Court

contemporaneously with the filing of the declaration of taking, [he] would have been able to earn

compound interest. Id. (quoting United States v. 319.46 Acres of Land, 508 F. Supp. 288, 291

(W.D. Okla. 1981)).

[27]

The Government admits that in some instances, compound interest may be required to

meet the just compensation requirement of the Fifth Amendment, Appellees Br. at 10 (citing

Kirby Forest Indus., Inc. v. United States, 467 U.S. 1, 10 (1984); Innovair Aviation, Ltd. v.

United States, 83 Fed. Cl. 498, 507 (2008)), but retorts that simple interest should be awarded

unless special circumstances dictate otherwise, id. at 9. The Government contends that in this

case, there are no special circumstances that would justify an award of compound interest and

the Superior Court did not abuse its discretion when it refused to make such an award. Id. at 10

[28]

The trial court, in denying Ilagan compound interest, relied upon this courts holding in

Guam United Warehouse Corp. v. DeWitt Transportation Services of Guam, Inc., 2003 Guam

20, wherein this court held that [t]he silence of a statute to specifically allow for compound

interest means that the interest shall be calculated on the basis of simple interest rather than

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 15 of 17

compound interest in the absence of some special circumstance dictating otherwise. DeWitt,

2003 Guam 20 38 (quoting Norman v. Norman, 506 N.W.2d 254, 256 (Mich. Ct. App. 1993)).

The trial court stated that [c]onsidering that the language of 21 G.C.A. 15107 is silent

regarding compound interest . . . , the Court discerns no statutory authority for imposing

compound interest . . . . RA, tab 254 at 4 (Dec. & Order).

[29]

Just as the trial court erred in simply relying on the prescription of a 6% statutory rate of

interest as determinative of the issue of the proper rate to be applied to the deficiency in this

case, the court likewise erred in relying on the silence in 21 GCA 15107 as being dispositive of

the issue of whether compound, rather than simple, interest should be awarded. In DeWitt, this

court considered whether compound interest was required by 18 GCA 47106, which concerns

the legal rate of interest on loans.4 Clearly, the proper rate of interest in such a situation can be

set by the legislature. As discussed above, however, the determination of the rate of interest

required to provide just compensation in a condemnation proceeding is a judicial, rather than a

legislative, function. Therefore, unlike an award of interest on a loan, the trial court is not bound

by the silence in 21 GCA 15107 when determining whether or not compound interest is

required to provide a condemnee interest sufficient to satisfy the just compensation

requirement of the Fifth Amendment. See, e.g., Otay Mesa Prop., L.P. v. United States, 779 F.3d

1315, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (The Supreme Court has long held that just compensation

includes interest compounded from the date of a taking when payment for the taking does not

4

Title 18 GCA 47106 provides:

47106. Legal Rate of Interest.

The rate of interest upon the loan or forbearance of any money, goods or things in action,

or on accounts after demand or judgment rendered in any court of the territory, shall be six percent

(6%) per annum but it shall be competent for the parties to any loan or forbearance of any money,

goods or things in action to contract in writing for a rate of interest not exceeding the rates of

interest specified in Title 14 of this Code.

18 GCA 47106 (2005).

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 16 of 17

coincide with the taking itself. (citing Phelps, 274 U.S. at 344; Seaboard, 261 U.S at 306));

429.59 Acres of Land, 612 F.2d at 465 (Nor did the Commission err by compounding the 6.635

average rate of interest to arrive at a figure of 7.4 percent simple interest per annum.

Compounding of interest is appropriate to compensate the landowners for the loss of use of the

interest that the deficiency award would have been producing for them during the interim.);

Natl Food & Beverage Co. v. United States, 105 Fed. Cl. 679, 704 (2012) (The Federal Circuit

has mandated compound interest where it is necessary to accomplish complete justice under the

Takings Clause. (quoting Dynamics Corp. of Am. v. United States, 766 F.2d 518, 520 (Fed. Cir.

1985))). Thus, the trial court erred in simply relying upon the silence in the statute as being

dispositive of the issue; where, as here, the condemnee argues that simple interest would be

inadequate and presents evidence in support of an award of compound interest, the court should

assess whether such compounding of interest is necessary to satisfy the requirement of just

compensation.

[30]

We find that compounding of interest is necessary to provide just compensation in this

case. Again, 34 years have passed since the time of the taking. If the Government had deposited

the full value of the property in 1981 ($45,000.00), Ilagan would have been able to earn

compound interest on that amount. Compound interest is necessary to compensate Ilagan for the

loss of use of the interest that the deficiency award would have been producing for him during

the interim. See 429.59 Acres of Land, 612 F.2d at 465.

V. CONCLUSION

[31]

The determination of the proper rate of interest to satisfy the requirement of just

compensation in a takings case is a judicial, rather than a legislative, function. Therefore, courts

are not bound by the statutory interest rate.

The statutory rate, however, is entitled to a

Govt of Guam v. 162.40 Square Meters of Land, 2016 Guam 10, Opinion

Page 17 of 17

presumption of reasonableness, which may be rebutted by a landowner seeking compensation

above the statutory rate. The trial court erred in failing to consider Ilagans evidence regarding

his entitlement to a rate above the 6% provided in 21 GCA 15107. The matter is remanded to

the trial court to determine in the first instance whether under the circumstances of this case,

Ilagan is entitled to an interest rate above the statutory rate. In reaching such decision, the trial

court is to rely on the evidence already in the record regarding the applicable interest rates

through January 2008, and open the record to new evidence only on the applicable interest rates

since that date.

[32]

Additionally, we determine that compounding of interest is necessary to provide Ilagan

the just compensation to which he is entitled.

[33]

Accordingly, we REVERSE and REMAND for further proceedings not inconsistent

with this opinion.

/s/

____________________________________

JOHN A. MANGLONA

Justice Pro Tempore

/s/

____________________________________

ALBERTO E. TOLENTINO

Justice Pro Tempore

/s/

____________________________________

ALEXANDRO C. CASTRO

Presiding Justice Pro Tempore

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Final AssignmentDocument11 pagesFinal Assignmentapi-553037030No ratings yet

- The VigilanteDocument5 pagesThe VigilanteibiaixmNo ratings yet

- History of Nursing Law in The Philippines EditedDocument12 pagesHistory of Nursing Law in The Philippines Editedjandipot_kurikuripotNo ratings yet

- Watson Memorial Spiritual Temple of Christ v. Korban, No. 24-0055 (La. June 28, 2024)Document24 pagesWatson Memorial Spiritual Temple of Christ v. Korban, No. 24-0055 (La. June 28, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Sojenhomer LLC v. Village of Egg Harbor, No. 2021ap1589 (Wis. June 19, 2024)Document45 pagesSojenhomer LLC v. Village of Egg Harbor, No. 2021ap1589 (Wis. June 19, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Roman Realty, LLC v. City of Morgantown, No. 22-587 (WV June 11, 2024)Document14 pagesRoman Realty, LLC v. City of Morgantown, No. 22-587 (WV June 11, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Surface Water Use Permit Applications, SCOT-21-0000581 (Haw. June 20, 2024)Document134 pagesSurface Water Use Permit Applications, SCOT-21-0000581 (Haw. June 20, 2024)RHT100% (1)

- Petition For A Writ of Certiorari, Romero v. Shih, No. 23-1153 (U.S. Apr. 23, 2024)Document296 pagesPetition For A Writ of Certiorari, Romero v. Shih, No. 23-1153 (U.S. Apr. 23, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- In Re DJK, LLC, No. 22-AP-269 (Vt. June 14, 2024)Document25 pagesIn Re DJK, LLC, No. 22-AP-269 (Vt. June 14, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Petition For Review, Shear Dev. Co., LLC v. Cal. Coastal Comm'n, No. S284378 (Cal. Apr. 2, 2024)Document54 pagesPetition For Review, Shear Dev. Co., LLC v. Cal. Coastal Comm'n, No. S284378 (Cal. Apr. 2, 2024)RHT100% (1)

- BMG Monroe I, LLC v. Village of Monroe, No. 22-1047 (2d Cir. Feb. 16, 2024)Document21 pagesBMG Monroe I, LLC v. Village of Monroe, No. 22-1047 (2d Cir. Feb. 16, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Petition For Writ of Certiorari, Bruce v. Ogden City Corp., No. 23-1260 (U.S. Jume 3, 2024)Document98 pagesPetition For Writ of Certiorari, Bruce v. Ogden City Corp., No. 23-1260 (U.S. Jume 3, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Petition For Writ of Certiorari, G-Max MGMT, Inc. v. State of New York, No. 23-1148 (U.S. Apr. 18, 2024)Document46 pagesPetition For Writ of Certiorari, G-Max MGMT, Inc. v. State of New York, No. 23-1148 (U.S. Apr. 18, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Lyman v. Lanser, No. 23-P-73 (Mass. App. Ct. Mar. 7, 2024)Document20 pagesLyman v. Lanser, No. 23-P-73 (Mass. App. Ct. Mar. 7, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Ontario Inc. v. City of Stratford, No. OLT-22-002455 (Ont. Land Trib. Jan. 11, 2024)Document64 pagesOntario Inc. v. City of Stratford, No. OLT-22-002455 (Ont. Land Trib. Jan. 11, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Devillier v. Texas, No. 22-913 (U.S. Apr. 16, 2023)Document9 pagesDevillier v. Texas, No. 22-913 (U.S. Apr. 16, 2023)RHTNo ratings yet

- Nicholson v. United States, No. 23-843 (Fed. Cl. Mar. 13, 2024)Document16 pagesNicholson v. United States, No. 23-843 (Fed. Cl. Mar. 13, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Petition For A Writ of Certiorari, Sawtooth Mountain Ranch, LLC v. U.S. Forest SVC., No. 22-1103 (U.S. Apr. 9, 2024)Document71 pagesPetition For A Writ of Certiorari, Sawtooth Mountain Ranch, LLC v. U.S. Forest SVC., No. 22-1103 (U.S. Apr. 9, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Petition For Review, Mojave Pistachios, LLC v. Superior Court, No. S284252 (Cal. Mar. 19, 2024)Document84 pagesPetition For Review, Mojave Pistachios, LLC v. Superior Court, No. S284252 (Cal. Mar. 19, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Maunalua Bay Beach Ohana 28 v. State of Hawaii, No. CAAP-19-0000776 (Haw. App. Mar. 18, 2024)Document24 pagesMaunalua Bay Beach Ohana 28 v. State of Hawaii, No. CAAP-19-0000776 (Haw. App. Mar. 18, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- HBC Victor LLC v. Town of Victor, No. 23-01347 (N.Y. App. Div. Mar. 22, 2024)Document4 pagesHBC Victor LLC v. Town of Victor, No. 23-01347 (N.Y. App. Div. Mar. 22, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Bar OrderDocument39 pagesBar OrderShea CarverNo ratings yet

- Sheetz v. County of El Dorado, No. 22-1074 (U.S. Apr. 12, 2024)Document20 pagesSheetz v. County of El Dorado, No. 22-1074 (U.S. Apr. 12, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Romero v. Shih, No. S275023 (Cal. Feb. 1, 2024)Document33 pagesRomero v. Shih, No. S275023 (Cal. Feb. 1, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Ocean State Tactical, LLC v. Rhode Island, No. 23-1072 (1st Cir. Mar. 7, 2024)Document34 pagesOcean State Tactical, LLC v. Rhode Island, No. 23-1072 (1st Cir. Mar. 7, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Kingston Rent Control Appellate Court DecisionDocument9 pagesKingston Rent Control Appellate Court DecisionDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- Agency of Transportation v. Timberlake Associates, LLC, No. 23-AP-059 (Vt. Mar. 2024)Document14 pagesAgency of Transportation v. Timberlake Associates, LLC, No. 23-AP-059 (Vt. Mar. 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Brief of Amicus Curiae Pacific Legal Foundation, Town of Apex v. Rubin, No. 206PA21 (N.C. Feb. 8, 2024)Document25 pagesBrief of Amicus Curiae Pacific Legal Foundation, Town of Apex v. Rubin, No. 206PA21 (N.C. Feb. 8, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- State Ex Rel. AWMS Water Solutions, LLC v. Mertz, No. 2023-0125 (Ohio Jan. 24, 2024)Document12 pagesState Ex Rel. AWMS Water Solutions, LLC v. Mertz, No. 2023-0125 (Ohio Jan. 24, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Gerlach v. Rokita, No 23-1792 (7th Cir. Mar. 6, 2024)Document12 pagesGerlach v. Rokita, No 23-1792 (7th Cir. Mar. 6, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Brief For Petitioner, Sheetz v. County of El Dorado, No. 22-1074 (U.S. Nov. 13, 2023)Document57 pagesBrief For Petitioner, Sheetz v. County of El Dorado, No. 22-1074 (U.S. Nov. 13, 2023)RHTNo ratings yet

- Call For Papers: "Too Far: Imagining The Future of Regulatory Takings"Document2 pagesCall For Papers: "Too Far: Imagining The Future of Regulatory Takings"RHTNo ratings yet

- Statement of Justice Thomas Respecting The Denials of Certiorari, 74 Pinehurst, LLC v. New York, No. 23-1130 (U.S. Feb. 202, 2024)Document2 pagesStatement of Justice Thomas Respecting The Denials of Certiorari, 74 Pinehurst, LLC v. New York, No. 23-1130 (U.S. Feb. 202, 2024)RHTNo ratings yet

- Compatibility of Domestic Anti-Avoidance Measures With Tax TreatiesDocument6 pagesCompatibility of Domestic Anti-Avoidance Measures With Tax TreatiesAnonymous jDkQEZ5OBFNo ratings yet

- Torts in Ireland - Look Inside SampleDocument102 pagesTorts in Ireland - Look Inside SampleRohit dNo ratings yet

- Social Work Practice With Gay Men, LesbianDocument30 pagesSocial Work Practice With Gay Men, Lesbianochoajulie87No ratings yet

- Women in Modern Arabic LiteratureDocument5 pagesWomen in Modern Arabic LiteratureDaniela TunaruNo ratings yet

- Florida GUN LAWDocument14 pagesFlorida GUN LAWdwnsouf77100% (1)

- NPIA Police UK Madeleine McCannDocument1 pageNPIA Police UK Madeleine McCannJoana MoraisNo ratings yet

- Vistara Free Ticket Voucher TC FinalDocument2 pagesVistara Free Ticket Voucher TC FinalSanjenbam SumitNo ratings yet

- James Gorman Resignation RequestDocument15 pagesJames Gorman Resignation RequestLeon R. KoziolNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography Enc 2135Document4 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Enc 2135api-385372879No ratings yet

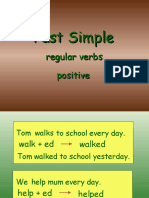

- Past-Simple-Regular-Verbs - 111111111Document35 pagesPast-Simple-Regular-Verbs - 111111111api-639734400No ratings yet

- A Small Response To Prof. Makau Mutua On His Push For Gayism in KenyaDocument2 pagesA Small Response To Prof. Makau Mutua On His Push For Gayism in KenyaMisheck MutuaNo ratings yet

- Weiss V Credit Bureau of Napa County Inc Chase Receivables FDCPA Complaint PDFDocument14 pagesWeiss V Credit Bureau of Napa County Inc Chase Receivables FDCPA Complaint PDFghostgripNo ratings yet

- Ryanair Boarding PassDocument2 pagesRyanair Boarding PassRavi ShankarNo ratings yet

- Praveen CriminalDocument18 pagesPraveen CriminalSurya GNo ratings yet

- In Re: Need That Law Student Be Actually Supervised (Bar Matter No. 70)Document2 pagesIn Re: Need That Law Student Be Actually Supervised (Bar Matter No. 70)CMLNo ratings yet

- Faction DemandsDocument22 pagesFaction DemandsAeneas WoodNo ratings yet

- Delivery Permit - AFTDocument1 pageDelivery Permit - AFTPaul ObispoNo ratings yet

- 112 Preliminary InvestigationDocument1 page112 Preliminary InvestigationElijahBactolNo ratings yet

- Sheikh Zayed Medical College SZMC Open Merit List 2013Document11 pagesSheikh Zayed Medical College SZMC Open Merit List 2013Shawn Parker0% (1)

- RiatavinDocument4 pagesRiatavinSirShamefulNo ratings yet

- 25 Capitol Medical Center Vs MerisDocument1 page25 Capitol Medical Center Vs MerisMariam PetillaNo ratings yet

- Excessive Force, Wrongful Death and Inadequate Medical Care of Travis Banks LawsuitDocument22 pagesExcessive Force, Wrongful Death and Inadequate Medical Care of Travis Banks LawsuitMeganNo ratings yet

- CIR V BurmeisterDocument3 pagesCIR V BurmeisterGenevieve Kristine Manalac100% (1)

- Appointment Letter FormatDocument6 pagesAppointment Letter FormatAmit PandeyNo ratings yet

- 73 Freedom of The Press USDocument7 pages73 Freedom of The Press USRicardo Bautista100% (1)

- Handbook GoodwillDocument73 pagesHandbook Goodwillkey2careersNo ratings yet

- Matiosaitis and Others v. LithuaniaDocument2 pagesMatiosaitis and Others v. LithuaniaLAdyAgataNo ratings yet