Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nautilus, Inc.

Nautilus, Inc.

Uploaded by

collie0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views14 pagescase

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentcase

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views14 pagesNautilus, Inc.

Nautilus, Inc.

Uploaded by

colliecase

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 14

NAUTILUS, INC.

CASE 9

"The problem in this industry is that you just have to take a long-term view of

things. You have to be actively engaged in finding a solution to what may be the

problem-after-next long before you have finished implementing the solution to the major

current one. The growth potential in this field is enormous but so are the headaches.

Our sales growth last year caught us completely by surprise and we are into the bank

for $1 million of short-term money. if our new stock offering works out, we shall have

“iaken care of that problem, but | am already worrying about how we can finance the

investments | know we shall have to make in 1977 and in 1973 - and in 1977. And all

my figures may be underestimates. According to my projection our sales in 1977 could

be just 10 times what we expect them to be this year, and some of the decisions we.

nave to make right now are going to control whether that potential is realized.”

Background

In May, 1968, the speaker, Paul Godwin, was the financial vice president of

Nautilus, Inc., a small manufacturing company located in a small Texas city. “The

company had been started in early 1963 by two engineers, Guy Olson and Laurence

Crawford, to produce improved types of undersea free-diving equipment, a field in

which both men had had previous work experience. Each had contributed his entire

savings to the venture: $15,000 from Mr. Olson and $25,000 from Mr. Crawford. The

initial capitalization consisted of 8,000 shares, $5 par, which the founders held in

proportion to their cash contributions: Mr. Olson, 3,000 shares and Mr. Crawford, 5,000.

The firm's first products, a powerful spotlight for underwater use and an

electrically powered propulsion unit, had been marketed in the spring of 1964 and had

been immediately successful. Mr. Godwin, a friend of Mr. Olson's, had joined the

company at this time as business manager and had invested “his*own savings of

316,000 in the company. In view of the progress already made by the company in

developing two products to the point of production feasibility; it was agreed that Mr.

Godwin should Duy into the company at @ price of $8 per SS-par share, giving him a

holding of 2,000 shares.

Believing that the most promising area of’ development was likely to be in

underwater communications and electronics applications, the founders hired three more

engineers in the fall of 1964 to work in this field. Two government contracts were also

obtained at this time.

The company continued to be successful, and sales grew from $400,000 in 1964

to $2.6 million in 1966. The most serious problems encountered were financial ones.

Although the venture was clearly undercapitalized, the founders were very unwilling to

sell any equity interest in the company at that time. The task of finding funds to support

the expansion fell to Mr. Godwin. The government research contracts, for study into

problems of life-support during prolonged submersion in underwater laboratory

structures, provided a useful flow of payments; but extensive use had also to be made

of secured bank borrowing and supplier credit. All earings were retained in the

company, the three stockholders paying themselves modest salaries and no dividends.

The financial problems reached crisis proportions during 1967. The company

had anticipated continued growth in both its existing sales lines and its contract work

Projections for 1967, however, did not include expectations of large sales from new

products. In midyear a range of special-purpose trawl devices for the collection of

marine botanical and biological specimens from the seabed were announced and

received some publicity in academic journals. The new products generated immediate

interest. By August, 1867, demand for both the new and some of the older products

was considerably in excess of supply. It became apparent that 1967 revenues would

reach $4 million. More world people were hurriedly recruited, and an additional factory

building was leased. The need to finance additional wage bills, lease payments, and

inventories of raw materials and subcomponents presented a very serious problem,

forcing Mr. Godwin to call upon the company's banking connection for assistance,

The company had since its inception made use of a medium-sized commercial

bank located nearby.’ The original line of credit granted had been secured by notes

endorsed by the two founders and by the assignment of accounts receivable. As the

organization began to demonstrate its competence and to attain profitable operation,

the requirement for endorsement had been dropped and the bank had steadily

increased its loan as Nautilus’ operations expanded. The need for additional funds in

late 1967, however, was far greater than anything the company had yet experienced

Mr. Godwin met a number of times with the bank's vice president in charge of loans,

and ultimately with its president. The bank officers, though very unhappy about the

situation, decided to continue their support of the company, and by the end of 1967

Nautilus’ short-term indebtedness to the bank approached $1 million.”

The president of the bank made it very clear that he considered this a rescue

operation and that he would insist on the replacement of this short-term indebtedness

by long-term funds as quickly as possible. He urged that the company should increase

the equity portion of its capitalization and suggested that the record sales in the past

year would make it possible to sell stock at an attractive price. He offered to introduce

Mr. Godwin to an investment banking house in Houston with which his own bank

“in Texas, branch banking is not allowed.

2"The balance sheet and income statement for 1967 are provided in Exhibits 1 and 2.

maintained an excellent relationship. Mr. Godwin expressed interest in this proposal

and undertook to discuss the matter with Mr. Olson and Mr. Crawford

The founders of Nautilus quickly faced up to the realities of the situation and

agreed that the reluctance to sell any part of their equity in the firm might have to be

abandoned if the current rate of growth was to be maintained. They held a first meeting

with representatives of the investment bank, Parker, Marsh and Charleton, one week

later.

After analyzing the financial and operating data supplied by the company, the

(Shder of the banking team, Mr. Marsh, outlined a possible offering of stock to the

Public, He advised that in order to retire the short-term debt, provide a basis for some

jonger-term borrowing, and support further growth in the next few years, it would be

necessary to sell enough stock to produce proceeds of about $2 million for the

company. Mr. Marsh suggested that 500,000 shares of new common stock should be

authorized, of which 300,000 shares would go to the founders and Mr. Godwin in

exchange for their present shares and in proportion to them. Of the remainder, 150,000

shares would be offered to the public at a price of $15 a share.* The issue would be

underwritten by @ syndicate headed by Parker, Marsh and Charleton at a spread of

10%, making the net proceeds to the company $2,025,000. He advised the company to

set aside $100,000 to cover the legal and other costs of the issue.

Mr. Marsh also requested that a seat be created on the board of directors for a

member of his firm and stated that the firm would press for the initiation of cash

dividends on the common shares, at a level of approximately 50% of net eamings, after

a few years. He explained that he and his partners dealt with many investors who

insisted on the prospect of dividend income as well as capital gains. If this source of

money could not be tapped, the stock would not sell for $15 per share, in his opinion*

The company executives met with Mr. Marsh on several more occasions during

the following month. Mr. Olson and Mr. Crawford, in spite of their reluctance to sell any

stock to outsiders, were eventually convinced that such a move was inevitable. They

agreed that a stock issue of 10,000 shares should be offered to the public at a price of

$15, as Mr. Marsh had suggested. Parker, Marsh and Charleton gave a firm agreement

to act as underwriters for the offering. The offer was to be made in July, 1968. The

bankers would use their best efforts to distribute the shares in lots not greater than 200

shares to one investor, thus creating the basis for trading in the "after market.”

° On the basis of 1967 net profits and @ total of 450,00 shares issued, this price was approximately 23

times current eamings, after tax.

ne directors could not promise publicly to declare dividends In the future, but they might be permitted to

say that dividends would be considered.

Mr. Godwin's Position in May, I968

In mid-May, 1968, Mr. Godwin was reviewing the company's financial situation

The decision to implement Mr. Marsh's proposed new equity financing had been taken,

and the necessary legal and accounting work had begun. The bank had expressed its,

willingness to continue its existing short-term loans until the funds from the sales of

stock became available. Thus, no immediate problem existed. The continuing financial

crisis of the past year had been a very disturbing experience, however, and Mr. Godwin

wanted to ensure that future needs for funds were anticipated and plans to meet these

needs were formulated before another such crisis could arise. He realized that he would

have to turn much more of his attention to forecasting the company’s financial

requirements and that the starting point for any such planning must be an estimate of

future company growth.

Mr. Godwin was by no means certain that he agreed with Mr. Marsh's suggestion

that a cash dividend should be introduced on the common stock. Mr. Marsh had argued

that notwithstanding rapid growth in revenues over the past two. years, the company

was still litle known and could not yet be considered to have an established “track

record.” Often new issues, after a period of popularity, subsided into a dull "thin" market

with very few shares traded. It was his opinion that the inauguration of a cash dividend

policy would make the investing public recognize that the company had “matured,” and

bid for the stock more actively.

Mr. Godwin believed that three powerful counterarguments might be advanced.

He felt that any investor who bought stock in a small company in a relatively new

industry such as this one was probably more interested in long-term capital gains than

in dividend incame. In the second place, he knew that Mr. Olson, Mr. Crawford, and he

himself did not need such income. Their tax liability positions gave them good reason to

prefer to see the funds left in the company rather than paid out in cash dividends. Any

cash dividends received by the principals were very likely to be reinvested in the

company, in fact, so that in their case the only benefit from the proposed dividend policy

would be to the government. Finally, and most seriously, he believed that it would be a

grave mistake to make any decision about cash dividends without first examining the

company's future needs for cash and trying to determine the consequences of a cash

dividend policy for the company’s subsequent new financing and future rate of growth.

Mr. Godwin decided that the problem was sufficiently important and complex to justify

obtaining outside assistance and that the company should use the services of a

consultant.

Building the Planning Structure

During the spring of 1987 Mr. Godwin had attended an executive development

program at a major business school, and had developed cordial relations with a number

of professors at the school. He was aware that many faculty members undertook

consulting assignments and decided to invite Professor Martin Ross, who had taught

financial management on the program, to consult with Nautilus, Inc., during the summer

months: A long-distance telephone conversation In may; 1968, followed by @ backup

letter outlining the situation, convinced Professor Ross that the project might be both

interesting and a useful source of new teaching material. It was arranged that he would

make his first visit to the company early in June.

Mr. Godwin and Professor Ross decided at their first meeting that the initial

requitement was to try to determine what the company's growth rate might be over the

planning period if no financial constraints existed: that is, in circumstances in which the

factors limiting growth were the time required to develop new products and new

research strength, and the development of market demand for these products and

capabilities, but not the need for funds to finance additional working capital, plant,

equipment, or other facilities. They decided that the professor's first step should be to

talk to all those people in the organization whose knowledge and responsibilities

qualified them to contribute to the formulation of such an estimate. During the next few

weeks Professor Ross discussed his requirements with Mr. Olson, Mr. Crawford, the

marketing manager, project leaders and other scientists, and representatives of the

government agencies for whom much of the research and development work was being

performed.

An initial problem was the choice of a planning horizon. Forecasts of market

demand for even existing products could not be made with any confidence more than 2

or 3 years into the future. On the other hand, some of the projects on which the

research groups were currently working would not begin to produce revenues until the

mid-1970's. Many long lead-time, high-technology projects had recently been

undertaken, particularly in the areas of “artificial gill’ and thin-membrane breathing

devices, low-frequency underwater radio transmission, and undersea transportation,

Although it was extremely difficult to estimate the size and timing of revenues from

these projects, it was expected that they would represent a major part of the company’s

activities. The representatives of government agencies were confident that their

budgets for the general area of oceanography research and development would be

rapidly increased in the next decade; but they found it difficult to forecast the

proportions of these budgets that would be devoted to hardware purchases, hardware

development, and long-term theoretical research.

The consultant finally decided, nevertheless, that the long-lead-time nature of

many of the firm's activities dictated a relatively long planning horizon and that a 10-

year period would be the most meaningful one despite the uncertainty that must attach

to the figures estimated for the later years in the planning period. He regarded his work

as a study of feasibility rather than an actual forecast.

The sales figures gathered by Professor Ross from his various sources and

combined by him to form the top line of his forecast (see Exhibit 3) revealed that the

company's growth potential over the coming decade wes very great, Mr. Godwin later

commented on the projection: "These figures force us to think in terms of a growth rate

that | would probably never have considered. Of course, | know they are not accurate,

especially for the later years. But even if the margin of error proves to be as much as

plus-or-minus 25%, the exercise has been a very valuable one. We were tending to feel

that the equity financing we expect next month would really get us off the hook and give

us a big enough base for our expansion for some years 10 come, But if we face up to

the challenge of these figures, well, we are going to need a lot more cash quite soon.”

Having estimated total revenues for every year of the planning period, the

consuitant's next step was to forecast net eamings in each year. He decides that it was

unrealistic to try to forecast profit margins for individual products. The alternative

chosen was to assume a ratio of earings before interest and taxes (E.B.I.T.) to total

revenues. In the 1967 financial year, this had been approximately 15%, A moderate

improvement upon this figure was expected, however, when new facilities were in full

operation and higher volumes had been achieved. Making allowance on this basis, he

estimated that the company should be able to produce net before-tax earings of at

least 16% of revenues, and used this basis as background for the before-tax figures

given in Exhibit 3.

In determining the company's needs for new funds during the planning period,

Professor Ross decided to try to obtain estimates of actual costs for new capital

investments but to estimate additional working capital requirements as a ratio of

working capital to net sales based on the company's past experience. The capital

investment figures were based on existing expansion plans and studies and discussion

with the company's research, engineering, and production executives. The assumption

underlying the calculation of new working capital requirements was that the working

capital exclusive of cash would approximate 28% of net sales, as had been the case in

recent weeks.

Professor Ross, in estimating depreciation charges, used the double declining

balance method, consistent with the company's practice.’ It was now possible to

complete the schedule given as Exhibit 3, which was an attempt to present the

company's inflows and outflows of funds over a 10-year period, exclusive of all matters

related to financing. Since there was a negative cash change for each period, it was

clear that the very rapid expansion of the company would not be feasible without the

introduction of new funds. Of course, the company was about to receive $1.9 million,

approximately, from the sale of shares. But about $1 million of this was to be used to

pay off the bank. Obviously, the net new funds provided would be consumed early in

1970.

The president of the commercial bank serving Nautilus, Inc., had indicated his

opinion that the company should in the future ensure that the equity should constitute at

least two thirds of the company's total capitalization.’ Mr, Godwin asked Professor Ross

5 Since Professor Ross worked from a detailed property schedule, the user of this case cannot check his

figures.

* Capitalization is defined as the total of all assets, less the current lablitles. That is itis the total of the

long-term debts and all the acccunts belonging to the stockholder interest.

to assume that the company would consistently use debt up to but not in excess of this

limit. Calculating from the figures in the balance sheet of Exhibit 2, and the estimated

earnings of 1968, Professor Ross found that $1,578,000 new debt could be created.”

Some of it, doubtless, would be based on receivables, and the rest would be in a form

still undecided

Continuing the one-third debt assumption, and assuming a,6% before tax cost

on borrowed money, Professor Ross prepared Exhibit 4, which showed that by

reinvesting earings and borrowing up to one third of the capitalization the company

would experience cash shortages in 1971 and 1972.

Professor Ross pointed out to Mr. Godwin that the shortages in 1971 and 1972

could be covered by reducing the net working capital balance from 28% to 25%, and it

was decided to assume that this temporary change could be made. Nevertheless, it

was observed that there were signals of possible financial stringency within 3 years,

The obvious next step was to make a similar projection using the same

estimates of revenues, eamings, and expenditures but assuming a consistent cash

dividend policy of paying out 50% of net after-tax earings beginning in 1973, after the

cash shortage had disappeared, The result is given as Exhibit 5 (a). Little explanation of

this projection is tequired. The line showing the cumulative excess (deficit) in cash if no

new equity financing were undertaken indicates an increasing deficit. That is, the

introduction of a cash dividend policy would mean that the company could only attain its

maximum potential growth rate if further funds from external financing were introduced.

‘The professor calculated the extent of the new equity financing that would be required,

making full allowance for the increase in debt capacity that would accompany any

injection of equity funds. The result is summarized in Exhibit (b). After the $2 million

stock issue planned for 1968 it would become necessary to raise at least $1 million of

new equity in 1973, $2 million in 1974, $2.5 million in 1976, and $1 million in 1977.

No one could predict, of course, whether the financial markets would accept the

proposed issues or, if they did, at what price per share. Mr. Godwin believed that the

policy reflected in Exhibit 5(b) could not be accepted as a feasible altemative by the

founders of the company

The choice facing the company's directors was not confined to the two courses

of action already explored: either abandoning the cash dividend proposal or paying

cash dividends and accepting the need for continuing new equity financing. A third

possibility was to adopt the cash dividend policy from 1973 on, decide not to undertake

” Equity 12/81/67 $1,306

‘Added by stock sale 2,000

‘Added by net after-tax earnings, 1968, 402

Equity 12/31/68 sa.208

Permissible debt — one third of total

Capitalization (one half of equity) $1,854

Long-term debt 12/31/87 2268,

Net debt possible $1578

new equity financing. and accept a lower rate of growth in revenues and eamings

Professor Ross made a projection based on this policy also, He continued to assume

that debt would be used to the limit of the one-third capitalization rule, and reasoned

that the funds available for new working capital and capital investment in any period

would depend on the funds retained irom operations in the previous period plus new

debt capacity created by the retention of eamings. The available investment and

working capital funds would in turn determine the permissible expansion in sales, By

assuming an approximately linear relationship between sales and the fixed asset base

necessary to produce those sales, it was possible to construct a formula to predict total

revenues in each period. Professor Ross observed the amounts proposed in Exhibit 3

and saw that the relation of the increase in sales to the total of the increases in working

capital and other investments was approximately 1.2 to 1 in the period 1973-77.

The sales projections produced by this formula are shown in Exhibit 6. They

indicate a slower growth rate such that by 1977 the company's revenues would reach

approximately $42 million instead of the estimated maximum possible figure of $55

milion which might be attained under conditions of continuing capital adequacy. Net

earnings at the slower growth rate would increase to $3,164,000 in i977 instead of the

$4,096,000 forecast in Exhibit 4

A major problem remained, and Professor Ross felt that he must make it clear to

the Nautilus executives that it was their responsibility to decide upon what grounds this

problem should be resolved. He was certain that the interests and inclinations of Mr.

Olson, Mr. Crawford, and Mr. Godwin would be best served by the adoption of a policy

of maximum growth, no cash payout, and no further equity financing in the foreseeable

future. But from mid-1968 onwards, a minimum of 33% of the stock of the Nautilus

company would be in the hands of outside investors. The professor felt that some

account of the interests of this group should be taken in deciding on a financial policy.

Some of these new owners would no doubt value cash dividends more highly than did

the company's founders. He realized, also, that Mr. Godwin and his colleagues were

reluctant to undertake continued new equity financing largely because of the possible

dilution in their control of the company, and that other owners might well have no such

objections so long as any future stock offerings could be made at a share price that did

not dilute existing earnings per share. Similarly, the outside investors might be expected

to attach less value to revenue growth in absolute terms than did the inside group.

The alternative policy of cash dividends, no new equity financing, and limited

growth might be acceptable to these outsiders if it resulted in a pattern of cash

dividends plus capital appreciation per share in excess of the values offered by the

other policies. Professor Ross realized that to obtain a solution to this problem it would

be necessary to make some sweeping assumptions about the future prices of Nautilus

common stock and about the needs and characteristics of the investors who might be

expected to purchase the stock at the coming public stock offering

Professor Ross was also beginning to question whether the company's

commercial bankers were being both ungenerous and ultraconservative. The bank had

urged that debt should not make up more than 33 '/,% of total capitalization and that a

significant part of the proceeds of the new equity financing should be used to reduce

the existing short-term bank notes. It occurred to him that if the bank accepted a higher

debt ratio of, perhaps, 45%, or was willing to continue to provide a line of credit outside

the debt ratio, then it would be possible for the company to pay cash dividends, to avoid

new equity financing, and to enjoy a growth in revenues close to the maximum rate

shown in Exhibit 3. He wondered if one of the company officers should approach the

bank to discuss these possibilities, or even begin to look for another banking

relationship

Professor Ross and Mr. Godwin realized that they must very soon discuss the

company's financial strategies with Mr. Olson and Mr. Crawford. They wondered what

their recommendations should be.

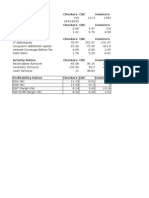

Exhibit 4

NAUTILUS, INC.

Income Statement for the Year Ended December 31, 1967

{in thousands)

Net sales revenues

100.0%

Cost of sales * (84.8)

Gross profit 15.1%

Interest expenses (1.4)

Other expense (0.4)

Net income before taxes 13.5%

Federal income tax 6.

Net income 15%

Retained earnings at beginning of period

Add: Net income

Total

Earnings per common share

* Including depreciation charges of $58,400.

Exhibit 2

NAUTILUS, INC.

Balance Sheet as of December 31, 1967

(in thousands)

Assets

Current assets

Cash

Accounts receivable

Inventories

Prepaid expenses

Total current assets

Fixed assets

Plant, equipment, and leasehold improvernents

Less: Accumulated depreciation

Net fixed assets

Total assets

Liabilities and Net Worth

Current liabilities

Notes payable to bank

Accounts payable

Unliquidated progress payments

Taxes payable and accruals

Total current liabilities

Mortgages payable

Loans from officers

Common stock (10,000 shares @ $5 par)

and capital surplus

Retained earnings

Total liabilities and net worth

oes ——_saBieyo yesouewy sx0jon sues

oe ‘asuadx9 u

0693 puny payesaued Ajeu.81

ou iu Uo seunBy yoeAL o} Uoqe;nD}e0 40 ayduses,

DOrTs GIES Gees TOHTS wars IS Hr

ons Ws Gos (ols

ose) oer) olez) (Ir)

(o0z'2) (o00'2)

eroueuy e099

yenuue

SIUOWSOAUI JOU,

oe" 029" $ oos'z

cay er ore ys xe} uoyeivexdeq

(sag') (061'») (osz'2) (srs) (9603) aansodxe xen

OLL'es oge's$ © OLI'Z$ OLz'S on'ys §— Sis't 060'1$ renuotod yseo Sujeredo xe} auoj9q

DOVSSE TOOTS ODTOS BOOST cose} DONS oosss soles 10N

ist 9L0b—«SLGhS GLEE ZL6L LSE OGL SOG 89GL

(spuesnoy,

JOUBUL JO OAISNIOXS UO! 14 Yseg pue ‘sBuWey ‘sajeg

‘ONT 'SMULNWN

ec ngiuxa

ra 99P ON

Poet

ees

ad

oo,

a0u'es

‘oul sy uo seunBy 49x91 0} wore !NO}eD Jo o1CUIES

aos'es pes'zs eea'es Ques GLS'LS GGUS SrIs eons xe} s0ye SBUUIES 10N

weer 2ST eS ere) = ie) Sh arr Seer ‘a6ueuo ongeinwng

(secs sas) Gas 491s esis (use)s (eeL)s Sires yenuue “yseo ut oBue45,

Toe aor yor Ta co

(yy) (Gee) (eoz) = an) (ae)

leyL oe" 386 6sL a2

{ove')$ (oovlg (a0zI$ (o0s}$ (ozais (ove'l)$ (oer'ts (oo0'Ls (aza) $

9u6h —SL6L_— BAGEL eL61 zL6L 1Gt GLE. «= G9GL_——B9GL

puesnoy) ul)

3 SpuIYL-oM e Bulunssy suoyoefos4 MO|4 USED

ONI 'SMULLAVN

puqixs

yonezieyde9 |e}. Ul LONISOg

Exhibit 5(a)

NAUTILUS, INC.

Cash Fiow Projection, Assuming 50% cash Dividend After 1972

1973 1974 1975 1976 1977

Funds profile, annual $(800) $(700)$(400) $1,740) $(400)

Cash dividend, 50% (1,133) (1,325) (1,515) (1,783) (2,090)

New debt at 33 '/, % ratio 567 663757 892 1,045

Interest (6%) on all debt (267) (301) 341) 386)——((440)

Tax shield from interest aerate 193220

Change in cash $(1,199) $(1,512) $(1,328) $(2,824) $(1,665)

Cash deficit, beginning of period (313)

Cumulative change 512) (3,024) (4,352) (7,176) (8,841

Net earnings after tax $2,267 $2,650 $3,030 $3,567 $4,180

Exhibit 5(b)

NAUTILUS, INC.

Cash Flow Projection, Assuming 50% Dividend Payout and Further Equity as Needed

(in thousands)

497319741975 1976 197

Funds profile, annual $(500) $(700) $(400) $(1,740) $400)

Cash dividend, 50% (1,133) (1,317) (1,482) (1,761) (2,048)

New equity 4,000 2,000 = 2500 1,000

New debt at 33 '/, % ratio 1,067 1,659 747 2,131 1,525

Interest (6%) on all debt (267) (331) (431) (475) (603)

Tax shield from interest 134 165 216 238 302

Change in cash $301 $1,477 $(1,360) $893 $(225)

Cash deficit, beginning of period 13)

Cumulative change 12) 1,465 105, 998 3

Net earings after tax $2,267 $2,835 $2,985 $3,523 $4,099

Maximum Sales Revenues Realizable with 50% Dividend Payout after 1972,

33 '/, % Debt Ratio, and No Equity Financing after 1968

Exhibit 6

NAUTILUS, INC.

(in thousands)

1973 19741975 1976 1977

Sales revenue $30,000 $32,362 $35,290 $38,603 $42,173

Before-tax operating cash potential $5,380 $5,788 $6,416 $6,976 $7,648

Tax exposure (50%) (2,690) (2,894) (3,208) (3.488) (3,824)

Depreciation tax shield 290 305 385 400 450

Internally generated funds, after tax $2,980 $3,199. $3,593 «$3,888 $4,274

New debt at 33 */, % ratio 567 610 664 725 794

Interest on all debt at 6%" (267) (301) (338) (378) (421)

Tax shield from interest 134 151 169 189 24

Cash dividend (1,133) (4,219) (1,327) (1,449) (4,582)

Cash deficit, beginning of period (gta) oe eesteeeeeeeaeen ae

Funds available to finance expansion in next period $1,968 $2,440 $2,761 $2,975 $3,273

Factor 12 1.2 1.2 4.2

Incremental sales in next period 3.570 3,928

Total sales in next period $42,173 $46,101

$2,899 $3,164

Net earnings after tax

“Interest computed on debt at the end of the previous year

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chapter1: Managers and ManagementDocument14 pagesChapter1: Managers and ManagementcollieNo ratings yet

- Gainesboro Machine Tools CorporationDocument15 pagesGainesboro Machine Tools CorporationcollieNo ratings yet

- The Motivation of A Rhodes ScholarDocument12 pagesThe Motivation of A Rhodes ScholarcollieNo ratings yet

- Motivation of Rhodes ScholarDocument1 pageMotivation of Rhodes ScholarcollieNo ratings yet

- Delicious IncDocument13 pagesDelicious InccollieNo ratings yet

- Deluxe CorporationDocument10 pagesDeluxe CorporationcollieNo ratings yet

- Krispy KremeDocument6 pagesKrispy KremecollieNo ratings yet

- BPI AM Organizational ChangesDocument3 pagesBPI AM Organizational ChangescollieNo ratings yet

- Emperador 2013Document114 pagesEmperador 2013collieNo ratings yet

- LP Formulation ExDocument32 pagesLP Formulation ExcollieNo ratings yet