Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Labor Relations Board v. Local 254, Building Service Employees International Union, Afl-Cio, Respondent, 376 F.2d 131, 1st Cir. (1967)

National Labor Relations Board v. Local 254, Building Service Employees International Union, Afl-Cio, Respondent, 376 F.2d 131, 1st Cir. (1967)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

National Labor Relations Board v. Local 254, Building Service Employees International Union, Afl-Cio, Respondent, 376 F.2d 131, 1st Cir. (1967)

National Labor Relations Board v. Local 254, Building Service Employees International Union, Afl-Cio, Respondent, 376 F.2d 131, 1st Cir. (1967)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

376 F.

2d 131

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Petitioner,

v.

LOCAL 254, BUILDING SERVICE EMPLOYEES

INTERNATIONAL UNION,

AFL-CIO,Respondent.

No. 6626.

United States Court of Appeals First Circuit.

April 10, 1967.

Elliott C. Lichtman, Washington, D.C., with whom Arnold Ordman, Gen.

Counsel, Dominick L. Manoli, Associate Gen. Counsel, Marcel MalletPrevost, Asst. Gen. Counsel, and Paul Elkind, Atty., Washington, D.C.,

were on petition for adjudication in civil contempt, for petitioner.

Harold B. Roitman, Boston, Mass., for respondent.

Bofore ALDRICH, Chief Judge, McENTEE, and COFFIN, Circuit

Judges.

ALDRICH, Chief Judge.

This is a petition to hold a union in civil contempt for violations of a Labor

Board order which we enforced following our opinion in NLRB v. Local 245,

Building Service Employees International Union, AFL-CIO, 1 Cir., 1966, 359

F.2d 289. Before stating our findings, we will recite the basis for that order.

Local 254, the union, represents employees of contract cleaners, who are

persons engaged in furnishing building cleaning and janitorial services, after

hours, to industrial and other concerns. One Kletjian, a contract cleaner doing

business as University Cleaning Company, at one time had a collective

bargaining agreement with the union, but upon his employees disassociating

themselves therefrom the contract was not renewed. The Board found that (in

some undetermined respect) the union and University had an existing labor

dispute. Concededly, some of University's employees do not receive all the

benefits that the union has obtained from some other cleaners.

In March and April, 1963, the union apprised the United Airlines' Boston

office, which employed University, that University was nonunion, was

undermining wage rates, and was destroying the union's 'public image.' When

United did nothing, the union threatened to picket, and did. The two pickets

carried signs saying, 'The contract cleaners employed here are not members of

Local 254, AFL-CIO.' They engaged in no physical obstruction, or even in

conversation. The picketing occurred during United's business hours, and never

while employees of University were on the premises. After two weeks it

stopped. Essentially the same pattern was followed at the place of business of

an A & P grocery store in Boston, another of University's customers.

In resisting the Board's finding that this was a violation of the act the union

phrased as its principal point on review, 'Whether picketing which is limited to

informing the public that cleaners employed at a location are nonunion is in

violation of Section 8(b)(4)(ii) B of the Act.' It argued to us that the 'picketing

activities * * * were limited to informational acts,' and that the union 'was

following the specific product, University cleaning service, to the appropriate

locations * * * where University operated and where the public could be alerted

to the facts.' For this it cited NLRB v. Fruit and Vegetable Packers (Tree

Fruits), 1964, 377 U.S. 58, 84 S.Ct. 1063, 12 L.Ed.2d 129. We held the reliance

misplaced, and agreed that the Board's finding of forbidden conduct directed

towards University's customers was warranted. The order that we enforced

forbade, 'threatening, coercing or restraining United Airlines, The Great

Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co., or any other person similarly engaged in commerce

or in an industry affecting commerce, where an object thereof is to force or

require them to cease doing business with Herbert Kletjian d/b/a University

Cleaning Co.'

The present petition alleges that beginning in August 1966 the union had

engaged in essentially the same conduct directed towards two other customers

of University, Craftsman Life Insurance Co. in Boston, and and Lewis Shepard

Products Co. in Watertown, both of which are in interstate commerce. The

union admitted certain conduct, but asserted what it claimed to be

distinguishing dissimilarities. The asserted dissimilarities, and our findings with

respect to them based upon evidence presented in open court, are as follows:

(1) The union did not notify Craftsman or Lewis Shepard in advance that

University was nonunion, or that it intended to picket, and had no conversations

with them at any time. We find this to be true, but immaterial. Picketing may

still be threatening even though it is carried on without notice, or in silence. The

party whose place of business is picketed does not need to be told orally what it

can read on the picket signs or reasonably infer therefrom.

6

(2) The union did not picket at all. This contention we reject entirely. There is

some small conflict in the testimony as to what the sign carriers actually did,

whether or not they were 'patrolling,' but it is agreed that they stood and

sometimes walked in front of the entrances of Craftsman and Lewis Shepard,

carrying signs and handing out leaflets. This unquestionably was picketing.

NLRB v. Local 182, Int'l Bhd. of Teamsters, 2 Cir., 1963, 314 F.2d 53.

(3) Respondent's principal contention is that its conduct was not directed

against Craftsman and Lewis Shepard, but was intended to inform potential

customers of University that it was nonunion. In reply to the natural query why,

if that was the objective, the union chose to picket secondary plants and not

University itself, union officials said they thought it likely that potential

customers of University might visit these secondaries to check University's

work.

We find this contention a transparent afterthought. Although University did

sometimes furnish the names of current customers to potential customers, it

suggested no inspection, and there was no evidence that any inspection was

ever made at Craftsman, Lewis Shepard, or anywhere else.1 The pickets

appeared during the business hours of the secondaries, not when University

employees were working. That a union would detail two men to spend full days

at commercial establishments in order to contact a possible person who might

come there to follow up work references strains credulity.

We might add that we think it far more likely, if the union was thinking of

prospective customers of University at all, that it thought of them in in terrorem

terms, viz., that it was informing them that if they employed University they,

too, could expect to be the object of secondary picketing. Since such future

picketing would itself be forbidden by our order, obviously this could not be a

protected informational activity.

10

The union's suggestion that its signs themselves indicated that there was no

dispute with the picketed secondaries must also be rejected. The signs (and the

leaflets that were handed out) read as follows:

11

'Unfair

12

University Cleaning Company is an unfair cleaner. University Cleaning

Company does not meet the union standards. Lewis Shepard Products Inc.

Watertown, American Electroplating Co., Harding Gross Inc., Seal-Rite of

Cambridge and Craftsman Insurance, Boston are using the services of this

unfair cleaner. This statement is directed to customers and the public only. It is

not a request to employees to refuse to pick up, deliver, or transport or refuse to

perform any services.

13

S.E.I.U. Local 254 AFL-CIO'

14

We do not read the sentence, 'This statement is directed to customers and the

public only.' as an assertion that it is directed to customers of University.

Coming as it does immediately after the listing of the concern whose premises

are being picketed, we read it, rather, as directed to the customers of that

concern, just as, admittedly, the sentence following quite obviously refers to the

employees of that concern.

15

If a sign could change the character of respondent's conduct so as to relieve it

from the consequence of an order, certainly this one did not. We find the

union's activities at Craftsman and Lewis Shepard to be clear and intentional

violations.2

16

We turn to a further matter, which occurred since the present petition was filed

and was introduced by amendment. On January 12, 1967 the Massachusetts

Department of Education opened bids for contract cleaning services at a

building that it was about to occupy, and it appeared that University had

submitted the lowest qualified bid. On the following day officials of the union

called upon an officer of the Department and asked that University not be

awarded the contract. Shortly thereafter, and before any award had finally been

made, pickets appeared at the main entrance of the building that then housed

the Department carrying signs saying, 'Mass. Department of Education Policies

Unfair to Local 254, AFL-CIO.' The Board has asked us to find this picketing in

violation of the order to cease threatening, coercing, or restraining 'any other

person similarly engaged in commerce' where an object thereof is to force or

require such secondary employers to cease doing business with University.

17

That the Department of Education is a 'person engaged in Commerce' we have

no doubt. One purpose of the 1959 amendments to section 8(b)(4), which

substituted the language 'any person engaged in commerce' for 'any employer,'

was to bring within the coverage of the section activities against entities such as

railroads and governmental units, which are specifically excluded from the act's

definition of 'employer.' See, e.g., S.Rep.No.187, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959)

at 80, in 1 Legislative History of the LMRDA 397, at 476, U.S.Code Cong. &

Admin.News 1959, p. 2318. Hence the Department seems clearly a 'person.'

Furthermore, it purchases substantial quantities of goods produced in other

states, and hence enters the flow of commerce. See, e.g., NLRB v. Baker Hotel

of Dallas, Inc., 5 Cir., 1963, 311 F.2d 528, 529.

18

Whether the union picketing of the Department violated the Board's order is

another matter. There are two complicating factors. In the first place, the words

'threaten, coerce, or restrain,' apparently have never been defined where the

object is a public agency. The Department of Education has no customers. The

appeal might be found to have been only to officials of the Department and the

general public. Secondly, we do not find the objective of this picketing entirely

clear. The union claims that procedures used in choosing the contract cleaners

who would be asked to submit bids, and the Department's policy of not

requiring contractors to comply with any minimum wage and benefit standards,

were unfair to it. At least taken by themselves these might be matters in

legitimate, primary dispute between the union and the Department. On the

other hand, these questions were raised only when the award of a contract to

University was imminent, and this award was concededly, at least in part, what

the union was attempting to prevent.3

19

We do not view this as a purely factual matter. Clearly we have jurisdiction, cf.

NLRB v. Bird Machine Co., 1 Cir., 1949, 174 F.2d 404, 406, so that naked

principles of primary jurisdiction, see, San Diego Bldg. Trades Council, etc. v.

Garmon, 1959, 359 U.S. 236, 242-243, 79 S.Ct. 773, 3 L.Ed.2d 775; Garner v.

Teamsters, etc. Union, 1953, 346 U.S. 485, 490-491, 74 S.Ct. 161, 98 L.Ed.

228; Myers v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp., 1938, 303 U.S. 41, 58 S.Ct. 459,

82 L.Ed. 638 do not apply. Nevertheless the principle announced in the primary

jurisdiction cases, that important questions of statutory interpretation should be

considered first by the Board, which has the major and initial responsibility for

enforcing the act, seems applicable here in our discretion.

20

The question whether section 8(b)(4) prohibits picketing designed to elicit a

public response to the actions of a government agency with which the union

may have both a primary and a secondary dispute is of particular importance.

The farther that picketing recedes from 'isolated evils' and the closer it comes to

the guarantees of the First Amendment, see Tree Fruits, supra, 377 U.S., at 63,

84 S.Ct. 1066, the more cautious we must be. Finding that the Department

picketing raises possibly difficult and substantially different questions from

those raised by the conduct that led to the Board's order, we decline to hold the

union in contempt so far as this picketing is concerned.

21

This action is intended to be without prejudice to any future Board action, in the

ordinary course, to determine whether the Department activity violated section

8(b)(4). Furthermore, it is not in recognition of the union's general claim that

we can never find it in contempt until the Board has first exhausted its

administrative procedures. In the normal course the court must be able to, and

will, proceed directly to enforce its own decree. NLRB v. Bird Machine Co.,

supra; NLRB v. M. Lowenstein & Sons, Inc., 2 Cir., 1941, 121 F.2d 673, 674;

see also NLBR v. Reed & Prince Mfg. Co., 1 Cir., 1952, 196 F.2d 755, 760.

Any other result would mean that even flagrant violations of an existing order

could go unpunished.

22

With respect to the Craftsman and Lewis Shepard matters the union is to be

adjudged in contempt. It may purge itself by making reimbursement to the

Board for all proper costs and expenses, including salaries, West Texas Utilities

Co. v. NLRB, 1953, 92 U.S.App.D.C. 224, 206 F.2d 442, cert. den.346 U.S.

855, 74 S.Ct. 70, 98 L.Ed. 369, incurred in the preparation and prosecution of

this petition, but not of the amendment, the amount thereof to be referred to this

court for determination and supplemental decree only in the event of

disagreement between the parties. NLRB v. Republican Publishing Co., 1 Cir.,

1950, 180 F.2d 437.

We disregard, as de minimis, testimony that came, incidentally, from Kletjian,

not the union, of a single inspection that took place four years before

This being a civil contempt, actual intent is immaterial. However, the defense

was so insubstantial, the union's principal witness even contradicting his own

affidavit by which summary judgment had been resisted, that we believe we

should take notice of the fact

Cases such as NLBR v. Local Union No. 313, Int'l Bhd. of Electrical Workers,

AFL-CIO, 3 Cir., 1958, 254 F.2d 221, which did involve a public agency,

related to coercion in an established sense-- urging employees and deliverymen

not to cross the picket line-- and involved the agency only as a secondary

employer

You might also like

- Narrative Report On Anti - BullyingDocument3 pagesNarrative Report On Anti - BullyingSarra Grande100% (1)

- Charles K. Burdick Origins Part I Columbia Law Review 1911Document19 pagesCharles K. Burdick Origins Part I Columbia Law Review 1911kurtnewmanNo ratings yet

- MPRE Exam PDFDocument21 pagesMPRE Exam PDFKat-Jean FisherNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 71. Docket 25300Document11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 71. Docket 25300Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Local 294, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America, 298 F.2d 105, 2d Cir. (1961)Document5 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Local 294, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America, 298 F.2d 105, 2d Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Desarrollos Metropolitanos, Inc. v. Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission, W. J. Usery, JR., Secretary of Labor, Party in Interest, 551 F.2d 874, 1st Cir. (1977)Document4 pagesDesarrollos Metropolitanos, Inc. v. Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission, W. J. Usery, JR., Secretary of Labor, Party in Interest, 551 F.2d 874, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Local 254, Building Service Employees International Union, Afl-Cio., 359 F.2d 289, 1st Cir. (1966)Document5 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Local 254, Building Service Employees International Union, Afl-Cio., 359 F.2d 289, 1st Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 14, Docket 25475Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 14, Docket 25475Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Graphic Arts Finishing Co., Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 380 F.2d 893, 4th Cir. (1967)Document6 pagesGraphic Arts Finishing Co., Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 380 F.2d 893, 4th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Local 294, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America, Independent, 317 F.2d 746, 2d Cir. (1963)Document10 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Local 294, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America, Independent, 317 F.2d 746, 2d Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board, Petitioner, v. Knitgoods Workers' Union, Local 155, International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, Afl-Cio, RespondentDocument6 pagesNational Labor Relations Board, Petitioner, v. Knitgoods Workers' Union, Local 155, International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, Afl-Cio, RespondentScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NLRB v. Servette, Inc., 377 U.S. 46 (1964)Document9 pagesNLRB v. Servette, Inc., 377 U.S. 46 (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sanjukta Paul's Marxist Legal HistoriographyDocument6 pagesSanjukta Paul's Marxist Legal HistoriographyVivek BalramNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Building Service Employees International Union, Local No. 105, 367 F.2d 227, 10th Cir. (1966)Document4 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Building Service Employees International Union, Local No. 105, 367 F.2d 227, 10th Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.: No. 17091. No. 17092Document7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.: No. 17091. No. 17092Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Local 803, International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders and Helpers of America, A.F.L., 218 F.2d 299, 3rd Cir. (1955)Document5 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Local 803, International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders and Helpers of America, A.F.L., 218 F.2d 299, 3rd Cir. (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Questions To Ask When Employees Are Disparaged by OutsidersDocument13 pagesQuestions To Ask When Employees Are Disparaged by Outsidersdan_michalukNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- John A. Piezonki, D/B/A Stover Steel Service v. National Labor Relations Board, 219 F.2d 879, 4th Cir. (1955)Document6 pagesJohn A. Piezonki, D/B/A Stover Steel Service v. National Labor Relations Board, 219 F.2d 879, 4th Cir. (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Friendly Ice Cream Corporation, 677 F.2d 170, 1st Cir. (1982)Document5 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Friendly Ice Cream Corporation, 677 F.2d 170, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. The Golub Corporation and Mechanicville Central, Inc., 388 F.2d 921, 2d Cir. (1967)Document13 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. The Golub Corporation and Mechanicville Central, Inc., 388 F.2d 921, 2d Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Melrose-Wakefield Hospital Association, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 615 F.2d 563, 1st Cir. (1980)Document10 pagesMelrose-Wakefield Hospital Association, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, 615 F.2d 563, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NLRB v. Steelworkers, 357 U.S. 357 (1958)Document10 pagesNLRB v. Steelworkers, 357 U.S. 357 (1958)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Labor Board v. Virginia Power Co., 314 U.S. 469 (1941)Document9 pagesLabor Board v. Virginia Power Co., 314 U.S. 469 (1941)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. American Coach Company, 379 F.2d 699, 10th Cir. (1967)Document4 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. American Coach Company, 379 F.2d 699, 10th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Employer Liability For Sexual Harassment in The Wake of FaragherDocument23 pagesEmployer Liability For Sexual Harassment in The Wake of FaragherPhương Thanh 12F Lê NgọcNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Rockwell Manufacturing Company (Du Bois Division), 271 F.2d 109, 3rd Cir. (1959)Document13 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Rockwell Manufacturing Company (Du Bois Division), 271 F.2d 109, 3rd Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hacking and Passing OffDocument2 pagesHacking and Passing OffCheranjit DasNo ratings yet

- Coca-Cola Case Study: An Ethics IncidentDocument19 pagesCoca-Cola Case Study: An Ethics IncidentCham ChoumNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Brown-Dunkin Company, Inc., 287 F.2d 17, 10th Cir. (1961)Document6 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Brown-Dunkin Company, Inc., 287 F.2d 17, 10th Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, P & C Food Markets, Inc., and American Stores Company, 340 F.2d 690, 2d Cir. (1965)Document9 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, P & C Food Markets, Inc., and American Stores Company, 340 F.2d 690, 2d Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Community Organization, 420 U.S. 50 (1975)Document21 pagesEmporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Community Organization, 420 U.S. 50 (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Weis Markets Inc v. NLRB, 4th Cir. (2001)Document15 pagesWeis Markets Inc v. NLRB, 4th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tupas v. NLRCDocument14 pagesTupas v. NLRCWinter WoodsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Local 239, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America, 340 F.2d 1020, 2d Cir. (1965)Document4 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Local 239, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America, 340 F.2d 1020, 2d Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Central Hardware Co. v. NLRB, 407 U.S. 539 (1972)Document7 pagesCentral Hardware Co. v. NLRB, 407 U.S. 539 (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 610 - Case Analysis 2Document7 pages610 - Case Analysis 2Ron BurkhardtNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. David Buttrick Company, 361 F.2d 300, 1st Cir. (1966)Document13 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. David Buttrick Company, 361 F.2d 300, 1st Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- J. P. Stevens & Co., Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, Textile Workers Union of America, Afl-Cio v. National Labor Relations Board, 449 F.2d 595, 4th Cir. (1971)Document7 pagesJ. P. Stevens & Co., Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, Textile Workers Union of America, Afl-Cio v. National Labor Relations Board, 449 F.2d 595, 4th Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Is Important in Determining Where A Plaintiff Can File A Civil Suit Because It Guarantees Both Parties "Due Process" of LawDocument3 pagesIs Important in Determining Where A Plaintiff Can File A Civil Suit Because It Guarantees Both Parties "Due Process" of LawnancyNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 53, Docket 23523Document12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 53, Docket 23523Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cases For LaborelDocument58 pagesCases For LaborelCecille Taguiam100% (1)

- National Labor Relations Board v. Rockaway News Supply Co., Inc, 197 F.2d 111, 2d Cir. (1952)Document9 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Rockaway News Supply Co., Inc, 197 F.2d 111, 2d Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tort of Vicarious LiabilityDocument95 pagesTort of Vicarious LiabilityFayia KortuNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument22 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- à Tna Finance Company v. James P. Mitchell, Secretary of Labor, United States Department of Labor, 247 F.2d 190, 1st Cir. (1957)Document6 pagesà Tna Finance Company v. James P. Mitchell, Secretary of Labor, United States Department of Labor, 247 F.2d 190, 1st Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Wright Line, A Division of Wright Line, Inc., 662 F.2d 899, 1st Cir. (1981)Document17 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Wright Line, A Division of Wright Line, Inc., 662 F.2d 899, 1st Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Building and Construction Trades Council of Delaware, 578 F.2d 55, 3rd Cir. (1978)Document6 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Building and Construction Trades Council of Delaware, 578 F.2d 55, 3rd Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- K & K Construction Co., Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, Local Union No. 399, United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, Afl-Cio, Intervenor, 592 F.2d 1228, 3rd Cir. (1979)Document9 pagesK & K Construction Co., Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, Local Union No. 399, United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, Afl-Cio, Intervenor, 592 F.2d 1228, 3rd Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Williams, 195 F.2d 669, 4th Cir. (1952)Document6 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Williams, 195 F.2d 669, 4th Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Corporation Cases Digest 3Document21 pagesCorporation Cases Digest 3Mariline LeeNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Trancoa Chemical Corporation, 303 F.2d 456, 1st Cir. (1962)Document8 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Trancoa Chemical Corporation, 303 F.2d 456, 1st Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Virginia Electric and Power Company v. National Labor Relations Board, 703 F.2d 79, 4th Cir. (1983)Document13 pagesVirginia Electric and Power Company v. National Labor Relations Board, 703 F.2d 79, 4th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Automotive Controls Corporation, 406 F.2d 221, 10th Cir. (1969)Document8 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Automotive Controls Corporation, 406 F.2d 221, 10th Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lipman Motors, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, and Amalgamated Laundry Workers, Joint Board, Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, Afl-Cio, Intervenor, 451 F.2d 823, 2d Cir. (1971)Document9 pagesLipman Motors, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board, and Amalgamated Laundry Workers, Joint Board, Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, Afl-Cio, Intervenor, 451 F.2d 823, 2d Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations Board v. Corning Glass Works Et AlDocument8 pagesNational Labor Relations Board v. Corning Glass Works Et AlScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Avoiding Workplace Discrimination: A Guide for Employers and EmployeesFrom EverandAvoiding Workplace Discrimination: A Guide for Employers and EmployeesNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document42 pagesChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Parker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Document24 pagesParker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Communication Made To International Criminal Court Requesting Investigation of Australia and Corporate ContractorsDocument115 pagesCommunication Made To International Criminal Court Requesting Investigation of Australia and Corporate Contractorsitamanko100% (3)

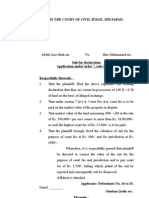

- In The Court of Civil Judge, ShujabadDocument3 pagesIn The Court of Civil Judge, Shujabadapi-3745637No ratings yet

- Crimrev Art. 6-12Document325 pagesCrimrev Art. 6-12alexfelices22No ratings yet

- Therapeutic 1 ADocument3 pagesTherapeutic 1 Avworldpeace yanibNo ratings yet

- code4-PPRA RULES PDFDocument116 pagescode4-PPRA RULES PDFaon waqasNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Injunction BriefDocument47 pagesPreliminary Injunction BriefPennLiveNo ratings yet

- Democracy Assessments: Tool SummaryDocument14 pagesDemocracy Assessments: Tool SummaryRuby GarciaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Donald Lyle Hassel, 341 F.2d 427, 4th Cir. (1965)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Donald Lyle Hassel, 341 F.2d 427, 4th Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Emily Dix - Criminal Law Outline!!!!Document109 pagesEmily Dix - Criminal Law Outline!!!!paulinennNo ratings yet

- LG Foods vs. AgraviadorDocument2 pagesLG Foods vs. AgraviadorJoshua Quentin Tarcelo100% (4)

- FORM-Retainer and Contingency AgreementDocument3 pagesFORM-Retainer and Contingency AgreementKim Grace PėqueNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Doronio V Heirs of DoronioDocument2 pagesHeirs of Doronio V Heirs of DoronioEPZ RELANo ratings yet

- Workbook Fast-Track To Member (As of 11-28-16) PDFDocument60 pagesWorkbook Fast-Track To Member (As of 11-28-16) PDFJacqueline Leoncia AlinoNo ratings yet

- Helvering v. Bruun, 309 U.S. 461 (1940)Document6 pagesHelvering v. Bruun, 309 U.S. 461 (1940)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- News Gathering PDFDocument2 pagesNews Gathering PDFAdvait ThiteNo ratings yet

- Herbert Glenn Polk v. Stephen Kaiser, Warden Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 991 F.2d 806, 10th Cir. (1993)Document3 pagesHerbert Glenn Polk v. Stephen Kaiser, Warden Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 991 F.2d 806, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People Vs Henry SalveronDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Henry SalveronAya Baclao100% (1)

- Legal Ethics CaseDocument6 pagesLegal Ethics Case1925habeascorpusNo ratings yet

- Marginaliztion and Tribes-1Document9 pagesMarginaliztion and Tribes-1Ashwini VijayakumarNo ratings yet

- PSCC V Quinones DigestDocument3 pagesPSCC V Quinones DigestMichael Parreño VillagraciaNo ratings yet

- Yo BroDocument2 pagesYo BroSaurabh YadavNo ratings yet

- External Aid of InterpretationDocument15 pagesExternal Aid of InterpretationOnindya MitraNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Solicitor General Ambrosio Padilla Assistant Solicitor General Esmeraldo Umali Bonifacio CandoDocument5 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Solicitor General Ambrosio Padilla Assistant Solicitor General Esmeraldo Umali Bonifacio CandoChristine Joy PamaNo ratings yet

- Ammathayee Ammal and Another - Appellant vs. Kumaresan and Others - RespondentDocument1 pageAmmathayee Ammal and Another - Appellant vs. Kumaresan and Others - RespondentNagaraja ReddyNo ratings yet

- ALWD-Bluebook Comparison ChartsDocument11 pagesALWD-Bluebook Comparison Chartsagung_wNo ratings yet

- Voluntary DealingsDocument17 pagesVoluntary DealingsdaryllNo ratings yet

- Unit 10 American ConstitutionDocument30 pagesUnit 10 American ConstitutionKhiết Tâm Thánh GiaNo ratings yet

- Serra Vs CA, RCBCDocument4 pagesSerra Vs CA, RCBCKling KingNo ratings yet