Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bumpus Decision

Bumpus Decision

Uploaded by

housingworks0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

560 views20 pagesNew York City Transit Authority and "jane doe" move for summary judgment dismissing complaint. Plaintiff alleges that on July 16, 2006 and July 25, 2006, plaintiff suffered emotional distress. Non-party City of New York moves, pursuant to CPLR 1012 (b) (2), for leave to intervene in support of constitutionality of SS 8-107 (4) (a)

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentNew York City Transit Authority and "jane doe" move for summary judgment dismissing complaint. Plaintiff alleges that on July 16, 2006 and July 25, 2006, plaintiff suffered emotional distress. Non-party City of New York moves, pursuant to CPLR 1012 (b) (2), for leave to intervene in support of constitutionality of SS 8-107 (4) (a)

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

560 views20 pagesBumpus Decision

Bumpus Decision

Uploaded by

housingworksNew York City Transit Authority and "jane doe" move for summary judgment dismissing complaint. Plaintiff alleges that on July 16, 2006 and July 25, 2006, plaintiff suffered emotional distress. Non-party City of New York moves, pursuant to CPLR 1012 (b) (2), for leave to intervene in support of constitutionality of SS 8-107 (4) (a)

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 20

SUPREME COURT

COUNTY OF KINGS, PART CSCP Index No.: 3512/2007

TRACY BUMPUS

Plain

against. a

DECISION/ORDER

NEW YORK CITY TRANSIT AUTHORITY and

“SANE DOE,” Hon. Kenneth P. Sherman

Defendants

Recitation, as required by CPLR §2219(a), of the papers considered in the review of this motion:

Papers Numbered

Notice of Motion and Affidavits Annexednvon-

‘Opposing Affidavits/A firmations

Reply Affidavits/A firmations..

‘Other papers submitted.

Upon the foregoing papers, defendants New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) and

Lorna Smith (sued as “Jane Doe” and, hereinafter, “Smith”, move for an order, pursuant to

CPLR 3212 granting them summary judgment dismissing the complaint. Non-party City of New

York (the “City”) moves, pursuant to CPLR 1012 (b) (2), for leave to intervene in support of the

constitutionality of § 8-107 (4) (a) of the Administrative Code of the City of New York (“§ 8-107

aay!

Background and Procedural History

‘The complaint asserts that on July 16, 2006 and July 25, 2006, plaintiff suffered

emotional distress caused by the acts and statements of Smith, On those days, plaintiff, a

Title 8 of the Administrative Code of the City of New York is sometimes referred to as the New York City

Human Rights Law.

transgender woman, entered the downtown side of the Nostrand Avenue A train subway station

(operated by NYCTA). Plaintiff alleges that on July 16, 2006, she asked Smith, aNYCTA

service employee, for assistance with using a MetroCard. Plaintiff alleges that Smith responded

with “a steady stream of discriminatory, transgender-phobic (“transphobic”) epithets at Ms.

Bumpus, verbally harassing her and haranguing her with vicious transphobie language in an

extremely loud voice, pointedly doing so publicly to humiliate and harass Ms. Bumpus."? On

July 25, 2006, Ms. Bumpus entered the Nostrand Avenue “A” train station, and once again

defendant, NYCTA employee Smith (while standing with another NYCTA employee), allegedly

recognized Ms. Bumpus, pointed at her and again commenced to verbally harass her and

harangue her with vicious transphobic language in an extremely loud voice, pointedly doing so

publicly to humiliate and harass Ms. Bumpus. This allegedly occurred after Ms. Bumpus made

a formal complaint and spoke with NYCTA Superintendent Mr. Clayton Moe on July 20, 2006

regarding the initial incident.

Thereafter, on October 10, 2006, plaintiff filed a notice of claim, pursuant to General

Municipal Law § 50-c, against the NYCTA. On December 7, 2006, plaintiff gave testimony at a

hearing held pursuant to General Municipal Law § 50-h. Lastly, on January 30, 2007, plaintiff

commenced the instant action against NYCTA.

Plaintiff asserts two causes of action in the complaint. ‘The first cause of action alleges

that NYCTA is liable for the “metal and emotional injuries and anguish, embarrassment,

psychological and mental distress” caused by Smith as a result of NYCTA’s negligent training,

supervision and retention of Smith. ‘The second cause of action alleges that “Doe {defendant

Smith], an employee of the NYCTA, wantonly, wrongfully and maliciously, with deliberate

? Paragraph 10 of the complaint (a copy of which is annexed as Exhibit 1 to defendants’ affidavits in

support of their motion) states that “[allthough [plaintiff] was born anatomically male, [she] has had a female gender

identity, an innate sense of being female, from a very carly age ... [she] lives and, ainong other things, dresses each

day as a woman .... [she] hes been on hormone therapy, prescribed by her doctor, to help change her physical

‘appearance to that of a woman.” This court will use feminine nouns and pronouns in referring to plaintiff, in

conformance with her gender identity (see also Bumpus v New York City Tr. Auth., 18 Misc 34 1131{A}, 2008 NY

Slip Op 50254{U}, n 1)

? Paragraph 12 of the complaint.

* Paragraph 21 of the complaint.

intent to injure, made declarations and took aetions to make Ms. Bumpus feel that her patronage

was unwelcome, objectionable and not accepted, desired or solicited at the Nostrand Avenue ‘A’

train subway station because she is a transgender woman.” Plaintiff concludes that Smith’s

actions constituted a violation of § 8-107 (4) (a) and caused the emotional injuries noted in the

first cause of action.

On March 19, 2007, defendant NYCTA moved to dismiss the complaint. In support of

its motion, NYCTA argued that: (1) plaintiff failed to state a cause of action against the NYCTA

for the negligent hiring, retention, supervision, or training of Smith; and (2) the NYCTA is

urisdictionally exempt from § 8-107 (4) (a) by virtue of the Public Authorities Law. By order

dated July 11, 2007, the motion was denied,

On August 9, 2007, NYCTA filed a notice of appeal from the July 11, 2007 decision and

on January 15, 2008, the Second Department of the Appellate Division affirmed the court's July

11, 2007 decision. On August 27, 2007, NYCTA interposed an answer,

On October 17, 2007, plaintiff filed an affirmation of service of the summons and

complaint on Smith. On November 9, 2007, Smith moved to dismiss the action as against her

arguing: (1) the summons and complaint were not timely served; and (2) since she is a public

iction of the anti-

employee, the Public Authorities Law exempts her from the juris.

discrimination provisions contained in the Administrative Code of the City of New York.

By decision and order dated February 13, 2008, the court denied Smith’s motion to dismiss

(Bumpus v New York City Tr. Auth., 18 Mise 3d 1131[A], 2008 NY Slip Op $0254[U). First,

the court rejected the contention that the action should be dismissed as against Smith for Inte

service of the summons and complaint. The court reasoned that:

“[sfince plaintiff was unaware of the name of the employee at the time of the

filing of the complaint, the Court finds that there has been a display of reasonable

ue diligence on the part of plaintiff in attempting to serve Doe-Smith, due to the

difficulty in finding the contact information, location of transit worker, common

nature ofthe transit workers last name ‘Smith,’ and the difficulty in having

service effected. . .. Accordingly, in the interest of justice, the Court finds good

* Paragraph 24 of the complaint

cause for the late service” (/d. at *3, citing Jordan v City of New York, 38 AD3d.

336 [2007]; Leader v Maroney, Ponzini & Spencer, 97 NY24 95 (2001).

The court also rejected the contention that the Public Authorities Law exempted Smith

from the anti-discrimination provisions contained in the Administrative Code of the City of New

York. In so doing, the court first noted that “[t]he New York City Human Rights Law sets forth

re history contemplates that the Law be independently

a broad purpose . [t]he legis!

construed with the aim of making it the most progressive in the nation” and that “[tJhe New York

City Human Rights Law was intended to be more protective than its state and federal

counterparts” (Id, at *4-5). Also, after reviewing relevant case law and certain amendments to

the Public Authorities Law, this court found that “the NYCTA is not exempt from local laws thet

do not interfere with the function and purpose of the Transit Authority” (Jd at *S). Noting that

the alleged behavior of Smith was outside the scope of her employment, and would in fact violate

NYCTA employee conduct rules, the court determined that the applicable provision of the New

York City Human Rights Law did not conflict with NYCTA duties, ‘Therefore, this court

reasoned, neither the NYCTA nor its employee Smith were exempt from the subject anti=

discrimination provision

On March 14, 2008, defendant Smith (proceeding as “Jane Doe”) filed a notice of appeal

of the February 13, 2008 order, By decision and order dated July 7, 2008, the Appellate Division

affirmed the court's February 13, 2008 order, by which the court permitted late service of process

on defendant Smith and rejected the argument that Smith was jurisdictionally exempt from the

Public Authorities Law (Bumpus v New York City Tr. Auth., 66 AD3d 26 [2009]). First, the

Appellate Division stated that plaintiff was entitled fo an extension of ime to serve process on

Smith pursuant to the interest-of justice standard of CPLR 306-b. Specifically, the Appellate

Division noted that:

“plaintiff's commencement of litigation against an unknown party, denominated

as ‘Jane Doe,’ aligns this case with others where service of process proves to be

uniquely difficult because of the nature of the challenge (see Redmond v Jamaica

Hosp. Med. Ctr., 29 AD3d 768, 770 [2006]; Greco v Renegades, Inc., 307 AD2d

711 [2003}; Kaulpa v Jackson, 3 Misc 3d 227 [2004}). Additionally, as noted by

the Supreme Court, Smith had a common surname, and the plaintiff did not

4

possess Smith’s work location and schedule until September 2007. Smith, in turn,

articulated no credible argument of prejudice resulting from the timing of service.

There is nothing in the record suggesting that the plaintiff's complaint lacks facial

merit, and indeed, Smith does not contest merit as an issue here. The length of the

delay in service is not particularly egregious under the circumstances, and service

was effected promptly by the plaintiff's counsel upon being advised of Smith's

work location and work schedule” (id. at 37).

Second, the Appellate Division affirmed the court’s rationale and disposition of Smith’s

argument concerning the Public Authorities Law, Specifically, the Appellate Division noted that:

“{clontrary to Smith’s contention, Public Authorities Law § 1266 (8) does not

exempt the NYCTA or its employees from all local laws affecting its activities

and operations, but rather, only those ‘conflicting with this title or any rule or

regulation’ of the NYCTA (see Tang v New York City Tr. Auth,, 55 AD3d 720

id.)

Plaintiff filed and served a note of issue, on November 12, 2009, indicating that the

instant action is ready for trial. On January 11,2010, defendants moved for summary judgment

dismissing the complaint. By order to show cause filed May 20, 2010, the City of New York

moved to intervene in the instant action opposing NYCTA's constitutional challenge to § 8-107

[2008}). No conflict has been shown to exist in the laws at issue here

(4) (a).

Arguments Advanced by Defendants

In support of their motion for summary judgment, defendants first assert that Smith's

alleged statements do not violate § 8-107 (4) (a). Defendants concede (for the purposes of this

argument) the alleged statements were both demeaning and based on plaintiff's gender identity

and expression. However, defendants argue that the text of § 8-107 (4) (a) applies only to

discriminatory statements that imply that the use of public accommodation by the target of the

statements is unwelcome or objectionable, and that the alleged statements by Smith did not

implicate plaintiff's use of the subway system. Thus defendants conclude the alleged

discriminatory statement did not imply that plaintif?’s “patronage or custom” of the subway

system was “unwelcome, objectionable or not acceptable, desired or solicited” and, therefore, the

alleged statements did not implicate § 8-107 (4) (a).

5

In the alternative, defendants argue that if defendants’ statements fall within § 8-107 (4)

(@) so that the provision is deemed to apply as plaintiff claims, then that would render the

provision unconstitutionally void for vagueness. Defendants claim that although the alleged

statements were rude, there is no basis for assuming that the rude statements express that

plaintiff's use of the subways is unwelcome. Defendants state that such an assumption would

deprive NYCTA of fair notice of what may lawfully be said in a similar setting. Defendants

conclude that any interpretation of § 8-107 (4) (a) that makes it applicable to disoriminatory

remarks devoid ofa statement that the patronage of a person is unwelcome would render § 8-107

(4) (@) void for vagueness. Defendants argue that § 8-107 (4) (a) does not apply to Smith because

the use of ©... employee” indicates that the prohibition applies to employees who are acting

‘within the scope of their employment when the statements were made and further that a similar-

worded State of New York statute* indicates that § 8-107 (4) (a) applies only to managers and

terpretation to the

supervisors of public accommodations. Defendants maintain that an

contrary would render all of the NYCTA’s 47,000 employees subject to liability for declarations

similar to the one allegedly made by Smith, Furthermore, without a limit in the application of §

8-107 (4) (a) to managerial and supervisory employees the result would be unconstitutional

overbreadth. Because plaintiff cannot sustain its claim for discrimination based on an

unconstitutional oF inapplicable statute, their derivative claim for the negligent training,

supervision and retention of Smith, must also fall.

In the alternative, defendants argue that the relevant facts do not support negligent

training, supervision and retention claims against NYCTA. First, NYCTA contends that such a

negligent supervision and retention claim against an employer must be supported by facts

demonstrating that the employer had reason to know of the subject employee’s propensity to

engage in the wrongful conduct. NYCTA argues that there is no evidence of this employee’s

propensity to engage in this manner of conduct, therefore, NYCTA is not subject to liability

under a negligent supervision or retention theory. Defendants acknowledge that Smith has not

had an ideal record of satisfactorily interacting with subway customers; however, defendants

assert that there is no record of Smith ever making transphobic or similar comments directed

6 Civil Rights Law § 40 (as amended by L 1913, ch 265),

6

against NYCTA customers prior to the instant action. Defendants state that Smith was the

subject of only two customer complaints that were later substantiated and these two complaints

did not involve any statement or conduct concerning gender or sex. Defendants conclude that

since any prior customer complaints about Smith did not involve allegations of the same

behavior that plaintiff alleges, Smith's negative work history is insufficient to sustain plaintif's

negligent supervision or retention derivative claims against the NYCTA,

Defendants further argue that plaintiff's negligent supervision or retention claims must be

dismissed because a sustainable negligent supervision or retention claims must be based on

underlying tortious conduct by the subject employee. Here, the underlying conduct is not

tortious but is instead the alleged violation of a statute. Defendants imply thatthe underlying

this court may not properly sustain a negligent

based solely on Smith’s violation

behavior must be a common-law tort, therefore,

supervision or retention claim against the employer, NYCTé

of § 8-107 (4) (a).

Lastly, defendants assert that plaintiff's allegation that NYCTA negligently trained Smith

lacks merit. Defendants maintain that a sustainable negligent training claim against an employer

requires proof that the employer had reason to know of the employee's propensity to engage in

the specific conduct that plaintiff alleges. Moreover, defendants state that a sustainable negligent

training claim requires proof that inadequate training led to the alleged wrong. Defendants argue

plaintiff has no such proof, there is no evidence prior to the date of the alleged incident that any

NYCTA employee ever made transphobie comments to any NYCTA customer. Additionally,

the NYCTA has long-established rules and an employee training program requiring its

employees to treat all customers with courtesy and respect, Defendants also claim that the

NYCTA disciplines employees who violate these conduct rules. Defendants assert there is no

evidence to support plaintiff’s negligent training derivative claim against the NYCTA. For these

reasons, defendants conclude that this court should grant their motion for summary judgment and

dismiss the complaint.

Arguments Advanced by Plaintiff

In opposition, plaintiff indicates that the Restoration Act of 2005 directs courts to

construe provisions of the New York City Human Rights Law independently of State and Federal

provisions, even when State and Federal provisions have comparable language. Plaintiff further

7

claims that the Restoration Act directs courts to construe the New York City Human Rights Law

as broadly as possible with a vision toward social justice and that courts have been directed to

treat the New York City Human Rights Law as providing additional civil rights protections above

” of State and Federal civil rights provisions. Plaintiff concludes that defendants?

the “Aloo:

attempt to suggest otherwise lacks merit

Noxt, plaintiff notes that her testimony and that of Smith conflict on every significant

issue, therefore, giving rise to issues of fact requiring that this court deny defendants’ motion for

summary judgment,

In opposition to defendants’ argument that Smith’s acts and statements did not implicate

plaintiff's use of the subway, plaintiff states that Smith refused to assist her with her defective

MetroCard, a customer service that an NYCTA employee should provide, Plaintiff reiterates that

Smith, instead of providing customer service, attacked her gender identity and barraged her with

transphobic epithets. Plaintiff argues that pursuant to § 8-107 (4) (a), even an indirect statement

that conveys a discriminatory animus is considered an unlawful discriminatory practice. More

specifically, plaintiff argues that the fact that Smith did not explicitly refer to plaintiffs use of

the subway while uttering discriminatory comments is not a defense to § 8-107 (4) (a). Here,

plaintiff claims that the statements made by Smith (while working as an NYCTA station agent)

were implicit statements indicating that plaintiff was unweleome on NYCTA’s subways because

she was a transgender woman, Therefore, making Smith’s statements actionable under § 8-107

(4) (@). Plaintiff claims that a statutory provision is unconstitutionally vague only if the subject

provision is incapable of a constitutional application. Further, that a “complained-of" provision

will be upheld so long as a reasonable person of ordinary intelligence would know that the

proscribed conduct is prohibited by law. Plaintiff asserts that § 8-107 (4) (a) has a

straightforward, understandable prohibition as applied to the instant action: an employee of a

public accommodation cannot act in a manner that is discriminatory towards the public,

suggesting that a member of the public is unwelcome. Plaintiff contends that defendants’

arguments suggesting § 8-107 (4) (a) is vague are without merit.

Moreover, plaintiff maintains § that 8-107 (4) (a) is not an unconstitutional restriction on

free speech, Plaintiff refers to the fact that certain categories of speech are not entitled to

constitutional protection and suggests that transphobic comments are among those incidents of

speech that are not protected. Plaintiff also notes that courts have sustained regulations on

8

speech against constitutional challenges if the regulations are aimed at secondary effects of

speech and further important social values. Plaintiff refers to § 8-107 (4) (a) as content-neutral

and not restrictive of ideas or political beliefs, rather a provision to regulate discriminatory

conduct, therefore, constitutional. Plaintiff rejects the contention that § 8-107 (4) (a) applies only

to supervisory or managerial employees or applies only to systemic discrimination and points to

the plain language of § 8-107 (4) (2), which renders it applicable to the instant matter. Plaintiff

argues that § 8-107 (4) (a) expressly applies to an “employee” as well as a “proprietor” or

“manager” and the alleged incidents occurred while Smith was uniformed and on duty with the

NYCTA. Plaintiff reasons that the inclusion of “employee” in § 8-107 (4) (a) indicates that the

provision applies to situations where the alleged discrimination is outside the scope of the

employee's duty and further argues that any other interpretation would defeat the broad anti-

discrimination purpose of § 8-107 (4) (a).

In plaintiff's derivative causes of action, she argues that as an employer, NYCTA, is

liable for its negligent supervision, retention and training of its employee Smith and that contrary

to defendants’ contentions, Smith’s NYCTA work history contains evidence of 16 incidents of

mistreating subway customers since 1991. Plaintiff indicates that this work history constitutes

adequate notice of underlying employee propensity for rude and belligerent conduct toward

customers coupled with the fuct that defendant employer was on notice of the first incident,

constitutes negligent supervision, retention and training, Plaintiff furthers the argument that

such a propensity may be established by merely a single incident of brutal or egregious employee

behavior. Plaintiff states that her formal complaint to NYCTA of the first incident (which

allegedly happened on July 16, 2006) serves as sufficient notice of Smith's propensity; therefore,

the NYCTA is subject to liability for Smith’s alleged behavior on July 25, 2006.

Plaintiff challenges defendants’ contention that a negligent supervision, retention or

training claim must be based on a common-law tort, Plaintiff indicates that although the

underlying employee wrong is often described as “tortious,” various courts have sustained

employer liability for employee violations of statutes as opposed to common-law duties. Plaintiff

notes that some of these courts have sustained employer liability based on employee sexual

harassment, discrimination and violations of the provisions of the New York City Human Rights

Law.

Plaintiff points out that in 2003, the definition of “gender” in the New York City Human

9

Rights Law was amended to include (among other things) gender identity. Plaintiff claims that

discovery in the instant matter has demonstrated that despite this added civil rights protection for

transgender persons, the NYCTA did not train its employees about transgender sensitivity until

after Smith’s alleged behavior. Plaintiff concludes that this constitutes sufficient evidence

fending to show that the NYCTA has negligently trained its employees with respect to the civil

rights of transgender subway customers. For these reasons, plaintiff argues that the instant

motion for summary judgment should be denied,

Arguments Advanced by City of New York

‘The City filed an Order to Show Cause, without opposition, for leave to intervene in this

action upon notice on or about April 14, 2010 that there was a constitutional challenge to § 8

107 (4) (a). In support of its position that the statute is constitutional, the City argues that § 8-

107 (4) (a) targets only discriminatory conduct and the secondary effects of discriminatory

conduct, and exerts a small burden on g narrow class of speech which does not warrant

heightened scrutiny. In support of this argument, the City claims that the provision is a content=

riminatory acts in public

neutral regulation of conduct, a regulation prohibiting di

accommodations. Further, that such a regulation is constitutional so Jong as it furthers an

important government interest that is unrelated to suppression of free expression and does not

burden speech more than necessary. The City asserts that the regulation is a permissible

restriction on the time, place and manner of speech. Such restrictions are constitutional so long

as they are narrowly tailored, based on a significant government interest other than the content of

speech, and do not foreclose other channels of communication, The City also claims that

restrictions targeting secondary effects of speech, without reference to the content of speech, are

considered justified. The City argues § 8-107 (4) (a) meets these standards in the instant matter.

They point out that the interest of government combating invidious discrimination is a

compelling interest, which exceeds the “important” or “significant” government interest

thresholds noted above. Further, § 8-107 (4) (a) regulates only conduct involving discrimination

ion may be used to communicate

in public accommodations; any other channel of communi

discriminatory ideas or beliefs. For these reasons, the City concludes that § 8-107 (4) (a) is a

permissible regulation of discriminatory conduct according to free speech doctrine.

The City disagrees with defendants’ contention that the New York City Human Rights

Law is preempted by or inconsistent with State law. In support, the City first notes appellate

10

authority upholding the application of the State Human Rights Law to discriminatory epithets in

the public accommodation context. The City rejects defendants” arguments concerning the scope

8-107 (4) (a), noting that State anti-discrimination provisions are not limited to supervisory

or managerial employees; the City concludes thet a City of New York provision may permissibly

hold non-managerial employees, such as Smith, liable for discrimination in the public

accommodation context. Similarly, the City rejects defendants” suggestion that § 8-107 (4) (a)

should not apply here because Smith's alleged conduct was outside the scope of employment, as

evidenced by the NYCTA’s civility and anti-discrimination employee policies. The City submits

that this argument lacks merit; if'an employer's intemal code of employee conduct were

sufficient to preclude employer liability, the New York City Human Rights Law would

essentially be rendered unenforceable. For these reasons, the City concludes that this court

should deny defendants’ motion for summary judgment

Discussion

1. Standards for Summary Judgment

Summary judgment is a drastic remedy that deprives a litigant of his or her day in court

and should thus only be employed when there is no doubt as to the absence of triable issues of

material fact (Kolivas v Kirchoff, 14 AD3d 49% [2005}; see also Andre v Pomeroy, 35 NY2d 361,

364 [1974)). However, a motion for summary judgment will be granted if, upon al the papers

and proof submitted, the cause of action or defense is established sufficiently to warrant directing

judgment in favor of any party as a matter of law (CPLR 3212 [b]; Gilbert Frank Corp. v

Federal Ins. Co., 10 NY2d 966, 967 [1988]; Zuckerman v City of New York, 49 NY2d 557, 562

[1980)), and the party opposing the motion for summary judgment fails to produce evidentiary

proof in admissible form sufficient to establish the existence of material issues of fact (Alvarez v

Prospect Hosp., 68 NY 2d 320, 324 [1986], citing Zuckerman, 49 NY2d at 562)

‘The proponents of a motion for summary judgment must first demonstrate entitlement to

judgment as a matter of law, tendering sufficient evidence to eliminate any material issues of fact

(Alvarez, 68 NY2d at 324; Zuckerman, 49 NY2d at 562; see also Winegrad v New York Univ,

Med Cr, 64 NY2d 851, 853 [1985]; Sillman v Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp,, 3 NY2d 395,

404 [1957}). The motion should be granted only when itis clear that no material and triable

issue of fact is presented (Di Mena & Sons v City of New York, 301 NY 118 [1950)). Ifthe

W

existence of an issue of fact is even arguable, summary judgment must be denied (Museums at

Stony Brooky Vil. of Patchogue Fire Dept., 146 AD2d 572 {1989}. Also, parties opposing a

‘motion for summary judgment are entitled to every favorable inference that may be drawn ftom

the pleadings, affidavits and competing contentions (Nicklas v Tedlen Realty Corp., 305 AD2d

385 [2003]; see also Abseizer v Kramer, 265 AD2d 356 [1999]; Gibson v American Export

Asbrandisen Lines, 125 AD2d 65, 74 [1987]; Sirychalski v Mekus, 54 AD2d 1068, 1069 [1976];

MeLaughlin v Thaima Realty Corp., 161 AD2d 383, 384 [1990]). Indeed, the trial court is

required to accept the opponents’ contentions as true and resolve all inferences in the manner

‘most favorable to opponents (Henderson v City of New York, 178 AD2¢ 129, 130 (1991})

Lastly, a party seeking summary judgment has the burden of establishing prima facie entitlement

to judgment as a matter of law by affirmatively demonstrating the merit ofa claim or defense,

rather than by pointing to gaps in the an opponent’s proof (Nationwide Prop. Cas. v Nestor, 6

AD3d 409, 410 [2004]; Kats v PRO Form Fitness,3 AD3d 474, 475 [2004]; Kucera y

Waldbaums Supermarkets, 304 AD2d 531, 532 [2003]).

2. The City of New York's Motion for Leave to Intervene

‘The City received notice, pursuant to CPLR 1012 (b) (2) and General City Law § 19 (2),

of a dispute about whether Administrative Code of the City of New York § 8-107 (4) (a) is

unconstitutional. Consequently, the City moves, pursuant to CPLR 1012 (b) (2), for leave to

intervene in this action and support the consttutionality of § 8-107 (4) (a). In applicable par,

CPLR 1012 (“Intervention as of right; notice to attomey-general, city, county, town or village

where constitutionality in issue”) states as follows:

“(b) Notice to attomey-general, city, county, town or village where

constitutionality in issue,

2. When the constitutionality of a local law, ordinance, rule or regulation ofa city,

county, town or village is involved in an action to which the city, county, town or

ion is not a party, such city, county, town or village

village that enacted the pro

shall be notified and permitted to intervene in support of its constitutionality.”

Accordingly, the motion must be granted, since CPLR 1012 (b) (2) commands that the city “shall

be... permitted to intervene” (see also People v Stepter, 1S NY3d 792 [2010] {summarily

12

granting motion of City of New York pursuant to CPLR 1012 (b) (2)]). Moreover, no party

opposes the motion. For these reasons, the City’s motion for leave to intervene is granted.

3. Statutory Interpretation of Administrative Code of the City of New York § 8-107 (4) (a)

Administrative Code of the City of New York § 8-107 (“Unlawful discriminatory

practices”) states, in applicable part, as follows:

“4, Public accommodations. a. It shall be an unlawful discriminatory practice for

any person, being the owner, lessee, proprietor, manager, superintendent, agent or

employee of any place or provider of public accommodation, because of the actual

or pereeived race, creed, color, national origin, age, gender, disability, marital

status, partnership status, sexual orientation or alienage or citizenship status of

any person, directly or indirectly, to refuse, withhold from or deny to such person

any of the accommodations, advantages, facilities or privileges thereof, or,

directly or indirectly, to make any declaration, publish, circulate, issue, display,

post or mail any written or printed communication, notice of advertisement, to the

effect that any of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of any

such place or provider shall be refused, withheld from or denied to any person on

account of race, creed, color, national origin, age, gender, disability, marital

status, partnership status, sexual orientation or alienage or citizenship status or

that the patronage or custom of any person belonging to, purporting to be, or

perceived to be, of any particular race, creed, color, national origin, age, gender,

disability, marital status, partnership status, sexual orientation or alienage or

citizenship status is unwelcome, objectionable or not acceptable, desired or

solicited.”

i] Rights Restoration Act of 2005 (Local Law No 85 of City of New

Also, the Local

York § | et seq. [2005]}—referred to as the Restoration Act—states that:

“The provisions of [the New York City Human Rights Law] shall be construed

liberally for the accomplishment of the uniquely broad and remedial purposes

thereof, regardless of whether federal or New York State civil and human rights

laws, including those laws with provisions comparably-worded to provisions of

13

this title, have been so construed” (Jd. at § 7).

The Restoration Act was enacted to “notif{y] courts that (a) they had to be aware that

some provisions of the [New York City Human Rights Law] were textually distinct from its state

and federal counterparts, (b) all provisions of the [New York City Human Rights Law] required

independent construction to accomplish the law’s uniquely broad purposes, and (c) cases that had

failed to respect these differences were being legislatively overruled” (Williams v Now York City

Hows, Auth. 61 AD3d 62, 67-68 [2009], lv denied 13 NY3d 702 [2009] feraphasis in original)

The Restoration Act and its subsequent interpretation compel this court to reject

defendants’ arguments advocating a limited construction of § 8-107 (4) (a). One example of

tbese contentions is one based on State Div, of Human Rights v McHarris Gift Co. (11 AD2A

813 [1979], afd 52 NY2d 813 [1980)). In McFlarris Gift, the Appellate Division interpreted

Executive Law § 296 (which has substantially the same language as § 8-107 [4] [a}) as

inapplicable to a gift shop that “displayed for sale novelties which demeaned persons of Polish

extraction” (id) and thus dismissed a complaint alleging discrimination; the Court of Appeals

affirmed for the reasons given by the Appellate Division (52 NY2d at 814),

Even assuming that MeHarris Gift is not sufficiently distinguishable and thus erstwhile

controlling, itis clear that in the wake of the Restoration Act, this court's interpretation of § 8

107 (4) (a) cannot be limited solely by interpretations of similar State or Federal anti-

discrimination provisions. Indeed, “interpretations of state or federal provisions worded

similarly to {the New York City Human Rights Law] may be used as aids in interpretation only to

the extent that the counterpart provisions are viewed ‘asa floor below which the City’s Human

Rights law cannot fall, rather than a ceiling above which the local law cannot rise” (Williams, 61

AD3d at 66, 67, citing Restoration Act § 7). ‘Thus, any contention by defendant that an

interpretation ofa similarly-worded but different provision than § 8-107 (4) (a) controls in this

matter lacks merit.

4. Scope and Applicability of Administrative Code of the City of New York § 8-107 (4) (a)

This court rejects defendants’ contention that § 8-107 (4) (a) does not apply to the instant

‘matter because Smith is a non-supervisory employee. The provision applies to any “owner,

lessee, proprietor, manager, superintendent, agent or employee of any place or provider of public

accommodation” (emphasis added). There is no authority limiting the language “agent or

14

employee of any place or provider of public accommodation” to only supervisors or managers;

indeed, this court js not permitted to reject the literal meaning of “agent” or “employee” unless it

is obvious that the literal reading does not reflect legislative intent (see e.g. A.J. Temple Marble

& Tile v Union Carbide Marble Care, 87 NY2d 574, 580-581 [1996], citing Matter of Schinasi,

277 NY 252, 259 [1938], rearg denied 278 NY 624 [1938]. Thus, since it is undisputed that

Smith was an NYCTA employee at the relevant times, she is an “employee” for the purposes of §

8-107 (4) (a). Moreover, there is no merit to defendants’ suggestion that § 8-107 (4) (a) only

applies to employees acting in conformance with employer policy...This suggestion leads to an

absurd, result, specifically that a provider of public accommodation could completely escape

liability under § 8-107 (4) (a) simply by creating a civility or anti-discrimination policy (ef

Zakrzewska v New School, 14 NY3d 469, 479-480 [2010] {noting that in certain instances an

employer can mitigate civil penalties and punitive damages for acts of employee by showing

affirmative anti-discrimination undertaking).

Further, this court rejects defendants" contention that § 8-107 (4) (a) does not apply to the

instant matter because Smith’s conduct did not explicitly involve plaintiff's patronage of the

subway system. First, giving plaintiff the benefit of every favorable inference (see e.g. Cortale v

Educational Testing Serv., 251 AD2d 528, 531 (1998}), plaintiff's testimony indicates that Smith

used transphobic insults after plaintiff requested help with her MetroCard, ‘Thus; a reasonable

trier of fact could conclude that Smith's behavior was discriminatory conduct suggesting that

Plaintiff's use of the subway was unwelcome, triggering § 8-107 (4) (a): Second, given the broad

goals of the New York City Human Rights Law, and the language in § 8-107 (4) (a) prohibiting

conduct “to the effect that” a transgender person (among others) is not welcome at the subway, it

is not dispositive that Smith did not make an explicit statement that plaintiff was not welcome in

the subway system because of her gender identity.. For the foregoing reasons, § 8-107 (4) (a)

applies to the alleged incident.

5. Negligent Retention, Supervision and Training

Generally speaking, an employer may be subject to liability for the tortious acts of its

employees under theories of negligent hiring, negligent retention, and negligent supervision

(Kenneth R. v Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, 229 AD2d 159, 161 [1997}; see also Hall »

‘Smathers, 240 NY 486 [1925]). As defendants correctly note, a necessary element of such

15

causes of action is that the employer knew or should have known of the employee’s propensity

for the conduct which caused the injury (Id; see also Ghaffari v North Rockland Cent, Sch. Dist,

23 AD3d 342, 343-344 [2005)).

In the instant matter, and giving plaintiff the benefit of every favorable inference (see eg

Cortale, 251 AD2d at 531), there is an issue of fact as to whether NYCTA should have known of

Smith's propensity to engage in uncivil conduct. Although defendants state that there are only

two substantiated subway customer complaints alleging discourteous behavior by Smith,

plaintiff notes that there are in fact 16 complaints against Smith that warranted internal NYCTA

investigations. Moreover, plaintiff correctly notes that some of these investigations have been

characterized as unsubstantiated when, to the contrary, the investigations were merely

discontinued without compelling reason, Indeed, there is evidence that the NYCTA simply

ifies the finding of a triable issue of

failed to respond to complaints about Smith; this alone ju:

fact (see e.g. Mercer v State of New York, 125 AD2d 376, 377 (1986)). For these reasons, a trier

of fact could properly conclude that Smith had a long history of mistreating subway customers.”

Additionally, and again giving plaintiff the benefit of every favorable inference (see e.g

Cortale, 251 AD2d at 531), discovery in this action has suggested that the NYCTA had not

trained Smith (or any of its employees) adequately. There is no indication that the NYCTA

reacted to the amendment § 8-102 (23) (Cefining “gender") to include gender identity as a

prohibited basis for discrimination in the public accommodation context, A reasonable trier of

fact could reasonably conclude that by failing to instruct Smith about sensitivity to gender

identity, NYCTA's failure to train proximately caused the alleged incident.

Defendants also suggest that negligent retention, supervision or training liability will not

attach unless the underlying employee conduct is “tortious”, a common-law tort. Here

defendants claim the violation of § 8-107 (4) (a) is not a common-law tort and thus does not

suffice as “tortious” employee conduct for negligent retention or supervision liability. This

7 Defendants note that none of Smith's negative customer history contains incidents of disrimination

agains transgender persons (or any other form of civil rights discrimination), Defendants" contention however that

plaintiff must show a history of precisely analogous conduct lacks merit. Indeed, in .1. v Cty of New York O86

AD2d 243 (2001), the Appellate Division simply tated that “fan employer may be lable forthe negligent hiring

and retention ofan emplayee when it knew or should have known of the employee's propensity to commit injury”

(la. at 245). The term “injury” is unqualified, suggesting that, contrary to defendants” argument, the alleged

propensity need not be limited to exactly the same type of injury,

16

argument fails, in Primeau v Town of Amherst (303 AD2d 1035 [2003]), the Appellate Division

suggested that the requirement of underlying employee wrongful behavior is met when “the

employee is individually liable for a tort or guilty of a claimed wrong against a third person” (Jd

at 1036 [emphasis added). Moreover, throughout this action, plaintiff has consistently

predicated negligence claims against NYCTA on Smith’s alleged violation of § 8-107 (4) (a) and

not a common-law tort, The Appellate Division hes already noted the legal sufficiency of

plaintiff's negligent supervision, retention, and training claims predicated on Smith’s alleged

violation of § 8-107 (4) (a) (Bumpus 47 AD3d at 654). Nothing that occurred in the discovery

phase indicates that such negligent supervision, retention, and training claims cannot be sustained

by the underlying violation of the New York City Human Rights Law. For these reasons, this

court denies dismissal of plaintiff's negligent retention, negligent supervision and negligent

training claims against NYCTA.

6. Constitutionality of Administrative Code of the City of New York § 8-107 (4) (a)

This court rejects defendants’ arguments that § 8-107 (4) (a) is unconstitutionally vague

(or subject to an interpretation which would render it unconstitutionally vague). The standard is

well-defined; “[a} statute, or a regulation, is “unconstitutionally vague if it fails to provide a

person of ordinary intelligence with a reasonable opportunity to know what is prohibited, and itis

written in a manner that permits or encourages arbitrary or discriminatory enforcement” (Ulster

Home Care, Inc. v Vacco, 96 NY2d 505, 509 [2001], citing People v Foley, 94 NY2d 668, 681

[2000] and People v Nelson, 69 NY2d 302, 307 [1987]). Moreover, and again contrary to

defendants’ contentions, a court reviewing a vagueness challenge should consider the subject

provision as applied to the aggrieved litigant; hypothetical applications of the subject provision

are not pertinent to the issue of vagueness (see e.g. People v Taylor, 9 NY3d 129, 150-151

[2007]; Ulster Home Care, 96 NY2d at 510 [“Plaintiffs should have been required to show that

the regulation was unconstitutional as applied to them. When a person's conduct falls within the

proscriptions of a regulation, ‘a vagueness challenge must be addressed to the facts before the

court’ ” (citations omitted)}; People v Nelson, 69 NY2d 302, 308 [1987] [“if the actions of the

* Defendants* arguments, in essence, concede that § 8-107 (4) (a) is not facially invalid; defendants do not

argue that the provision is “incapable of any valid application” (Siefel v Thompson, 415 US 452, 474 [1974))

7

defendants are plainly within the ambit of the statute, the court will not strain to imagine

‘marginal situations in which the application of the statute is not so clear”; Village of Hoffman

Estates v Flipside, Hoffinan Estates, Inc., 455 US 489, 495 [1982] [*A plaintiff who engages in

some conduct that is clearly proscribed cannot complain of the vagueness of the law as applied to

the conduct of others. A court should therefore examine the complainant's conduct before

analyzing other hypothetical applications of the law”)). Lastly, “perfect clarity and precise

guidance have never been required even of regulations that restrict expressive activity” (United

States v Williams, 553 US 285, 304 [2008], quoting Ward v Rock Against Racism, 491 US 781,

794 [1989)).

Here, the alleged behavior of Smith was “clearly proscribed” (id). Stripped to its

applicable parts, § 8-107 (4) (a) states that “[i}t shall be an unlawful discriminatory practice for

any... employee of any place or provider of public accommodation, because of the actual or

perceived... gender, . . . of any person. . directly or indirectly, to refuse, withhold from or

deny to such person any of the accommodations, advantages, facilities or privileges thereof, or,

directly or indirectly, to make any declaration, ... to the effect that any of the accommodations,

advantages, facilities and privileges of any such place or provider shall be refused, withheld from

or denied to any person on account of... gender, .. or that the patronage or custom of any

person belonging to, purporting to be, or perceived to be, of any ... gender, ... is unwelcome,

objectionable or not acceptable, desired or solicited.” Simply put, § 8-107 (4) (a) prohibits acts

or statements, by people employed in a public accommodation context, that would suggest a

customer is unwelcome because of her (among other things) gender. Since this prohibition

‘unquestionably applies to Smith’s alleged behavior, defendants may not challenge § 8-107 (4) (a)

on the vagueness ground based on other hypothetical situations in which § 8-107 (4) (a) may

apply (Village of Hoffinan Estates, 455 US at 494-495).

Nor is this court persuaded that § 8-107 (4) (a) is unconstitutionally overbroad. The

Supreme Court of the United States has stated that “a law may be overtumed as impermissibly

overbroad because a substantial number of its applications are unconstitutional, judged in

relation to the statute’s plainly legitimate sweep” (Washington State Grange v Washington State

Republican Party, 552 US 442, 449 n 6 [2008] [intemal quotations omitted], quoting New York v

Ferber, 458 US 747, 769-771 [1982] and Broadrick v Oklahoma, 413 US 601, 615 [1973))

18

Here, defendants cannot demonstrate thet a substantial number of applications of § 8-107 (4) (a)

are unconstitutional. First, as the City cozreetly notes, “[i}avidious private discrimination may be

characterized as a form of exercising feeedom of association protected by the First Amendment,

but it has never been accorded affirmative constitutional protections” (Hishon v King d

‘Spalding, 467 US 69, 78 [1984], quoting Norwood v Harrison, 413 US 455, 470 [1973])

Therefore, since § 8-107 (4) (a) prohibits only discriminatory acts and speech against potential

customers of public accommodation, and since such discrimination is not afforded constitutional

Protection, the provision does not implicate a “substantial number” (Washington State Grange,

552 US at 449 n 6) of unconstitutional applications.

Moreover, this court must respect the interplay between the alleged discriminatory speech

and the public service functions of the NYCTA and Smith, Although a different context, in

Pappas » Giuliani (290 F3d 143 [2002}, cert denied sub nom Pappas v Bloomberg, 539 US 143

{2003)), the United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, found no constitutional protection

for a City of New York policeman who anonymously sought charitable contributions with

ig anti-black and anti-semitic messages” (Id. at 145). ‘The New York City

“printed fliers convey

Police Department subsequently terminated the plaintiff in Pappas; he then filed an action

claiming that his termination violated his rights under the First Amendment of the United States

Constitution. The Court of Appeals, however, found that the dissemination of bigoted material

risked harm to the public service mission of the police department (Jd. at 147-148). Applying the

balancing test articulated in Pickering v Board of Education (391 US 563 [1968)), the Court of

Appeals found that Pappas’ right to free speech was not violated (Pappas, 290 F3d at 151)

Pappas is analogous to the instant matter, which involves an employee of a public service

company who allegedly engaged in bigoted behavior, properly attributed to her. ‘Therefore, as in

Pappas, the prohibition of bigoted behavior in the public accommodation context contained in §

8-107 (4) (a) does not violate the constitutional guarantee of free speech.?

° Defendants have asked this court to consider the recent Supreme Court decision of United States v Stevens

(_US_, 130 8 Ct 1577 (2010}), This coutt’s reading of Stevens does not affect this decision and order

Although Stevens involved fee speech doctrine, it essentially stood for the proposition that states and the Listed

States are not tree to create new categories of unprotected speech (Id. at 1986). This court likewise does not purport

to create a category of unprotected speech. Defendants argue that Stevens suggests that plantfP interpretation of §

8-107 (4) (a) renders it overbroad; for the reasons given above, this court disagrees,

19

In sum, this court rejects the constitutional challenges to § 8-107 (4) (a). Along with the

reasons given above, the court notes that the State of New York and its subdivisions, such as the

City, have a compelling interest in combating invidious discrimination (New York State Club

Assn, Ine. v City of New York, 487 US 1, 14 n 5 [1988)), suggesting that § 8-107 (4) (a) would

survive the most exacting scrutiny. Moreover, § 8-107 (4) (a) is sustainable as a regulation of a

transit system, which is not a “First Amendment forum” (see e.g. Lehman v City of Shaker

Heights, 418 US 298, 302-304 [1974]). Lastly, the subway system may be considered a limited

public forum; therefore, “[rJeasonable time, place, and manner regulations are permissible, and a

content-based prohibition must be narrowly drawn to effectuate a compelling state interest”

(Rosenberger v Rector & Visitors of Univ. of Va., 515 US 819, $29 [1995}).

Under the Rosenberger test, § 8-107 (4) (a) survives constitutional scrutiny. As stated

above, combating invidious discrimination is a compelling interest (New York State Club Assn,

Inc., 487 US at 14 n 5). Also, the restriction contained in § 8-107 (4) (a) is narrowly tailored—it

applies only in the public accommodation context, and only to agents of public accommodation

companies who engage in discriminatory conduct that suggest victims of bias are unwelcome:

For the foregoing reasons, this court rejects defendants’ constitutional challenges to § 8-107 (4)

@).

Conclusion

The motion of defendants New York City Transit Authority and Lorna Smith (sued as

“Jane Doc”) for summary judgment dismissing the complaint is denied,

The foregoing constitutes the decision and order of the court,

eee

ge ee inte

Kenneth P. Sherman

December 29, 2010

Justice Supreme Court

Hon. Kenneth P. Sherman, JSC

20

You might also like

- Civil Society and Communities Declaration To End HIV: Human Rights Must Come FirstDocument7 pagesCivil Society and Communities Declaration To End HIV: Human Rights Must Come FirsthousingworksNo ratings yet

- Coit v. Zavaras, 10th Cir. (2008)Document7 pagesCoit v. Zavaras, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lester Smith v. City of Pittsburgh, 764 F.2d 188, 3rd Cir. (1985)Document13 pagesLester Smith v. City of Pittsburgh, 764 F.2d 188, 3rd Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cotter v. City of Boston, 219 F.3d 31, 1st Cir. (2000)Document8 pagesCotter v. City of Boston, 219 F.3d 31, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Applicant-Appellee v. Superior Temporary Services, Inc., 56 F.3d 441, 2d Cir. (1995)Document13 pagesEqual Employment Opportunity Commission, Applicant-Appellee v. Superior Temporary Services, Inc., 56 F.3d 441, 2d Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Smith v. City of Tulsa, 10th Cir. (2010)Document8 pagesSmith v. City of Tulsa, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Geneva Butts v. The City of New York Department of Housing Preservation and Development, 990 F.2d 1397, 2d Cir. (1993)Document21 pagesGeneva Butts v. The City of New York Department of Housing Preservation and Development, 990 F.2d 1397, 2d Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hollander v. NYC Commission On Human RightsDocument5 pagesHollander v. NYC Commission On Human RightsStaci ZaretskyNo ratings yet

- Neil T. Mulrain v. Board of Selectmen of The Town of Leicester, 944 F.2d 23, 1st Cir. (1991)Document5 pagesNeil T. Mulrain v. Board of Selectmen of The Town of Leicester, 944 F.2d 23, 1st Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument7 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument6 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Josefina Legnani v. Alitalia Linee Aeree Italiane, S.P.A., 274 F.3d 683, 2d Cir. (2001)Document6 pagesJosefina Legnani v. Alitalia Linee Aeree Italiane, S.P.A., 274 F.3d 683, 2d Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument11 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re: C. Victor Mbakpuo, Christopher E. Smith v. Us Sprint Susanne Keating Lilian Grant, 52 F.3d 321, 4th Cir. (1995)Document5 pagesIn Re: C. Victor Mbakpuo, Christopher E. Smith v. Us Sprint Susanne Keating Lilian Grant, 52 F.3d 321, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- GEORGE A. ROSS, Appellant v. Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union Robert Baker, Co-Trustee CAROL CARLSON, Co-TrusteeDocument28 pagesGEORGE A. ROSS, Appellant v. Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union Robert Baker, Co-Trustee CAROL CARLSON, Co-TrusteeScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument9 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument34 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joanna Cieszkowska v. Gray Line New York, 295 F.3d 204, 2d Cir. (2002)Document3 pagesJoanna Cieszkowska v. Gray Line New York, 295 F.3d 204, 2d Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Family Code 271 Sanctions: Only Available Against Party - Not Attorney - Koehler v. Superior Court of San Mateo County - Family Law - Family Court - DivorceDocument10 pagesFamily Code 271 Sanctions: Only Available Against Party - Not Attorney - Koehler v. Superior Court of San Mateo County - Family Law - Family Court - DivorceCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Robert T. Deveraux v. William J. Geary, and Plaintiff-Class in Culbreath v. Dukakis, Intervenors-Appellees, 765 F.2d 268, 1st Cir. (1985)Document11 pagesRobert T. Deveraux v. William J. Geary, and Plaintiff-Class in Culbreath v. Dukakis, Intervenors-Appellees, 765 F.2d 268, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tammy Yori v. Stephanie Domitrovich, 3rd Cir. (2016)Document4 pagesTammy Yori v. Stephanie Domitrovich, 3rd Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tyrone Wright v. Thomas Lewis, Corrections Officer, Glenn Bearor and Jeffrey Hughes, 76 F.3d 57, 2d Cir. (1996)Document6 pagesTyrone Wright v. Thomas Lewis, Corrections Officer, Glenn Bearor and Jeffrey Hughes, 76 F.3d 57, 2d Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Guy L. Smith, Jr. v. Massachusetts Department of Correction, 936 F.2d 1390, 1st Cir. (1991)Document18 pagesGuy L. Smith, Jr. v. Massachusetts Department of Correction, 936 F.2d 1390, 1st Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Aaot Foreign Economic Association (Vo) Technostroyexport v. International Development and Trade Services, Inc., 139 F.3d 980, 2d Cir. (1998)Document4 pagesAaot Foreign Economic Association (Vo) Technostroyexport v. International Development and Trade Services, Inc., 139 F.3d 980, 2d Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CREW v. Cheney Et Al: Regarding VP Records: 10/14/08 - CREWs Motion For Memorandum in SupportDocument26 pagesCREW v. Cheney Et Al: Regarding VP Records: 10/14/08 - CREWs Motion For Memorandum in SupportCREWNo ratings yet

- Cronin v. Amesbury, 81 F.3d 257, 1st Cir. (1996)Document6 pagesCronin v. Amesbury, 81 F.3d 257, 1st Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Timothy Booth v. Churner, C.O. Workensher, Sgt. Rikus, Lt. W. Gardner, Capt, 206 F.3d 289, 3rd Cir. (2000)Document20 pagesTimothy Booth v. Churner, C.O. Workensher, Sgt. Rikus, Lt. W. Gardner, Capt, 206 F.3d 289, 3rd Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument2 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 34 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1577, 34 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 34,422 John J. Jones v. City of Somerville, 735 F.2d 5, 1st Cir. (1984)Document4 pages34 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 1577, 34 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 34,422 John J. Jones v. City of Somerville, 735 F.2d 5, 1st Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument6 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Schmitt v. Rice, 10th Cir. (2011)Document10 pagesSchmitt v. Rice, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States District Court For The Southern District of OhioDocument8 pagesUnited States District Court For The Southern District of OhioJ DoeNo ratings yet

- SNI NYS State Response To ObjectionsDocument12 pagesSNI NYS State Response To ObjectionsDaniel T. WarrenNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument7 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Romney Ballot Law Commission DecisionDocument42 pagesRomney Ballot Law Commission DecisionThe Washington PostNo ratings yet

- Latrelle Campbell v. Pierce County, Georgia, by and Through The Board of Commissioners of Pierce County, Troy Mattox, Foy Kimbrell, and Larry Thomas, 741 F.2d 1342, 11th Cir. (1984)Document6 pagesLatrelle Campbell v. Pierce County, Georgia, by and Through The Board of Commissioners of Pierce County, Troy Mattox, Foy Kimbrell, and Larry Thomas, 741 F.2d 1342, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Miles Christman v. Albert Skinner, 468 F.2d 723, 2d Cir. (1972)Document8 pagesMiles Christman v. Albert Skinner, 468 F.2d 723, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Circuit JudgesDocument20 pagesCircuit JudgesScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sciolino v. City of Newport News, 4th Cir. (2007)Document31 pagesSciolino v. City of Newport News, 4th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument10 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Holmes v. State of Utah, 10th Cir. (2007)Document27 pagesHolmes v. State of Utah, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tijerina v. Carver, 10th Cir. (2007)Document8 pagesTijerina v. Carver, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- A.m.# 07-09-13-SCDocument86 pagesA.m.# 07-09-13-SCJudge Florentino FloroNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joseph M. McDade, 28 F.3d 283, 3rd Cir. (1994)Document32 pagesUnited States v. Joseph M. McDade, 28 F.3d 283, 3rd Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joan Morrison v. John Johnson, Donald Smith, Edward Bartley, Kevin Mahar, David Peters, Theresa Palumbo, Lori Lehner, Daniel Hulihan, John Doe, and Jane Doe, No. 05-1369-Cv, 429 F.3d 48, 2d Cir. (2005)Document5 pagesJoan Morrison v. John Johnson, Donald Smith, Edward Bartley, Kevin Mahar, David Peters, Theresa Palumbo, Lori Lehner, Daniel Hulihan, John Doe, and Jane Doe, No. 05-1369-Cv, 429 F.3d 48, 2d Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument14 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument11 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Walter Friedl v. City of New York, New York City Human Resources Administration, and Mrs. Blackheath, Public Assistance Worker With the New York City Human Resources Administration, Members of the Temporary Release Committee of Queensboro Correctional Facility and Superintendent of Queensboro Correctional Facility, 210 F.3d 79, 2d Cir. (2000)Document11 pagesWalter Friedl v. City of New York, New York City Human Resources Administration, and Mrs. Blackheath, Public Assistance Worker With the New York City Human Resources Administration, Members of the Temporary Release Committee of Queensboro Correctional Facility and Superintendent of Queensboro Correctional Facility, 210 F.3d 79, 2d Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ole Miss Title IX Training Materials Say Rape Accusers Lie As "A Side Effect of Assault"Document23 pagesOle Miss Title IX Training Materials Say Rape Accusers Lie As "A Side Effect of Assault"The College FixNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument4 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument14 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Boston Environmental Sanitation Inspectors Association and John Curry v. City of Boston, 794 F.2d 12, 1st Cir. (1986)Document3 pagesBoston Environmental Sanitation Inspectors Association and John Curry v. City of Boston, 794 F.2d 12, 1st Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals For The Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Yarber File 1Document29 pagesYarber File 1the kingfishNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument12 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- H. Stanard v. Keith Nygren, 09-1487 (7th Cir. 2011) Court of Appeals For The Seventh CircuitDocument21 pagesH. Stanard v. Keith Nygren, 09-1487 (7th Cir. 2011) Court of Appeals For The Seventh CircuitJustice CaféNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 718 F.2d 1210 (1983)From EverandU.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 718 F.2d 1210 (1983)No ratings yet

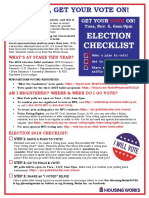

- Housing Works Get Out The Vote, Election Day 2018 Fact SheetDocument1 pageHousing Works Get Out The Vote, Election Day 2018 Fact SheethousingworksNo ratings yet

- Housing Works Get Out The Vote Election Day 2017Document1 pageHousing Works Get Out The Vote Election Day 2017housingworksNo ratings yet

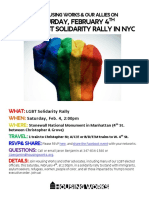

- NYC LGBT Solidarity Rally Flyer For 2 4 17 ExternalDocument1 pageNYC LGBT Solidarity Rally Flyer For 2 4 17 ExternalhousingworksNo ratings yet

- Housing Works "What's Your Voting Plan?!" Sheet 2018Document1 pageHousing Works "What's Your Voting Plan?!" Sheet 2018housingworksNo ratings yet

- Hillary Clinton Agenda and Meeting Notes 5.12.16Document9 pagesHillary Clinton Agenda and Meeting Notes 5.12.16Housing WorksNo ratings yet

- Braking AIDS Ride 2014. 9/12-9/14, Cheering Stations GuideDocument1 pageBraking AIDS Ride 2014. 9/12-9/14, Cheering Stations GuidehousingworksNo ratings yet

- #ICantBreathe/ Dec. 2014-Jan. 2015 Calls-to-Action Flyer, Housing Works Advocacy ActionsDocument2 pages#ICantBreathe/ Dec. 2014-Jan. 2015 Calls-to-Action Flyer, Housing Works Advocacy ActionshousingworksNo ratings yet

- May 2016 AIDS Advocates Consensus Policy Paper W EndorsersDocument17 pagesMay 2016 AIDS Advocates Consensus Policy Paper W EndorsershousingworksNo ratings yet

- Housing Works World AIDS Day 2014 CoalitionEvent FlyerSaveTheDate, EnglishDocument1 pageHousing Works World AIDS Day 2014 CoalitionEvent FlyerSaveTheDate, EnglishhousingworksNo ratings yet

- Advancing The National HIV/AIDS Strategy: Regional Listening SessionDocument4 pagesAdvancing The National HIV/AIDS Strategy: Regional Listening SessionhousingworksNo ratings yet

- Media Advisory 10.27 AIDS Community Press Conf RE Cuomo Ebola Quarantine FINALDocument1 pageMedia Advisory 10.27 AIDS Community Press Conf RE Cuomo Ebola Quarantine FINALhousingworksNo ratings yet

- Quarantine - Leadership Letter FINAL 10 26 14Document6 pagesQuarantine - Leadership Letter FINAL 10 26 14housingworksNo ratings yet

- NYC Festival of Forum and Legislative Theatre Cantgetright2014 PosterDocument1 pageNYC Festival of Forum and Legislative Theatre Cantgetright2014 PosterhousingworksNo ratings yet

- Task Force End of AIDS NYS, Opening Remarks, 10.14.14, CKingDocument3 pagesTask Force End of AIDS NYS, Opening Remarks, 10.14.14, CKinghousingworksNo ratings yet

- Brooks - Brooklyn ONAP Presentation 8.8.14Document4 pagesBrooks - Brooklyn ONAP Presentation 8.8.14housingworksNo ratings yet

- LGBT Equality & Justice Day 2014 Event Info Flyer, April 29, 2014, AlbanyDocument1 pageLGBT Equality & Justice Day 2014 Event Info Flyer, April 29, 2014, AlbanyhousingworksNo ratings yet