Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Running Head: Comparative Education

Running Head: Comparative Education

Uploaded by

api-127539041Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- TEACHERS DOING RESEARCH - The Power of Action Through Inquiry, Second EditionDocument413 pagesTEACHERS DOING RESEARCH - The Power of Action Through Inquiry, Second EditionKhôi Vương Tấn MinhNo ratings yet

- CISCO Ccna 200-301 Practice Test (Exam Questions)Document2 pagesCISCO Ccna 200-301 Practice Test (Exam Questions)Lin TorvaldNo ratings yet

- Japanese Education in The 21st CenturyDocument359 pagesJapanese Education in The 21st Centuryshihabjamaan100% (1)

- Education Systems of The PhilippinesDocument24 pagesEducation Systems of The PhilippinesRD OseñaNo ratings yet

- TUTOROO Tutors Introductory Guide PDFDocument4 pagesTUTOROO Tutors Introductory Guide PDFJuan Sebastian Quintero BoteroNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanDocument14 pagesA Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanBien R. Gruba IIINo ratings yet

- Curruculum of Education in UsaDocument4 pagesCurruculum of Education in UsaSHAFIRANo ratings yet

- High-Stakes Schooling: What We Can Learn from Japan's Experiences with Testing, Accountability, and Education ReformFrom EverandHigh-Stakes Schooling: What We Can Learn from Japan's Experiences with Testing, Accountability, and Education ReformNo ratings yet

- Comparative Education HandoutDocument4 pagesComparative Education Handoutapi-318154963No ratings yet

- The Current Education System in The United States of AmericaDocument5 pagesThe Current Education System in The United States of Americadayna-um100% (1)

- Smast RullDocument10 pagesSmast Rullaraakimoto94No ratings yet

- Education in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskDocument21 pagesEducation in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskArnel V. BagayanaNo ratings yet

- Quantitative ResearchDocument104 pagesQuantitative ResearchMary Joy HubillaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum in JapanDocument20 pagesCurriculum in JapanVanessa NacarNo ratings yet

- COMPARATIVE-ANALYSIS South-Korea Japan ChinaDocument12 pagesCOMPARATIVE-ANALYSIS South-Korea Japan Chinaeduardo bragaisNo ratings yet

- Gcu 114 Japanese Education ReportDocument4 pagesGcu 114 Japanese Education Reportapi-423109495No ratings yet

- Curriculum in Japan: Learning Chinese CharactersDocument21 pagesCurriculum in Japan: Learning Chinese CharactersjolinaNo ratings yet

- Education in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskDocument21 pagesEducation in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskMarvin OrbigoNo ratings yet

- Homework Policy in FinlandDocument4 pagesHomework Policy in Finlandafnaewonaoejmm100% (1)

- Curriculum in Japan: Presented To DR - Nadeem Presented by Sana AkramDocument18 pagesCurriculum in Japan: Presented To DR - Nadeem Presented by Sana AkramHina KaynatNo ratings yet

- Final Earning How To FixDocument2 pagesFinal Earning How To Fixapi-264385122No ratings yet

- Direct Instruction in MathematicsDocument29 pagesDirect Instruction in MathematicsJoyce LomibaoNo ratings yet

- Policy 3rdDocument19 pagesPolicy 3rdlemmademe204No ratings yet

- William Allan Kritsonis, PHDDocument11 pagesWilliam Allan Kritsonis, PHDWilliam Allan Kritsonis, PhD100% (1)

- American and Japanese EducationDocument13 pagesAmerican and Japanese Education1113892010100% (2)

- EducationDocument9 pagesEducationchsudheer291985No ratings yet

- 16.1 Education Around The World - Introduction To SocioDocument7 pages16.1 Education Around The World - Introduction To SocioМария РыжковаNo ratings yet

- Ap U S History Research Paper - Nishant Jain Rough DraftDocument20 pagesAp U S History Research Paper - Nishant Jain Rough Draftapi-319773246No ratings yet

- Critique On Educational Systems WorldwideDocument5 pagesCritique On Educational Systems WorldwideJohn Dominic RomeroNo ratings yet

- Educ 5010 Written Assigmt Unit 2Document6 pagesEduc 5010 Written Assigmt Unit 2Chris Emeka100% (1)

- What Happens During The School Day? Time Diaries From A National Sample of Elementary School TeachersDocument27 pagesWhat Happens During The School Day? Time Diaries From A National Sample of Elementary School TeachersSoledad VercellinoNo ratings yet

- Elementary School United States: Primary Education in The United States Children Pre-Kindergarten Secondary EducationDocument3 pagesElementary School United States: Primary Education in The United States Children Pre-Kindergarten Secondary Educationjaltamirano123No ratings yet

- Japan Country Case Study - Synthesis ReportDocument8 pagesJapan Country Case Study - Synthesis Reportapi-291966417No ratings yet

- Mem 646 - Comparative Educational Systmen, E - Education ApproachDocument30 pagesMem 646 - Comparative Educational Systmen, E - Education ApproachLengie Agustino - CobillaNo ratings yet

- Summer Reading LossDocument7 pagesSummer Reading Lossapi-259926624No ratings yet

- Position Argument - Uniting Education DraftDocument9 pagesPosition Argument - Uniting Education Draftapi-234201312No ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2pink_floydzNo ratings yet

- A Caring Errand 2: A Strategic Reading System for Content- Area Teachers and Future TeachersFrom EverandA Caring Errand 2: A Strategic Reading System for Content- Area Teachers and Future TeachersNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument10 pagesAnnotated BibliographyAlicia ElliottNo ratings yet

- Research Turnitin FinalDocument8 pagesResearch Turnitin Finalapi-559333472No ratings yet

- Unit: 4 Comparative Education in Developed Countries Education Theories and Practices in Japan: Education SystemDocument40 pagesUnit: 4 Comparative Education in Developed Countries Education Theories and Practices in Japan: Education SystemSyeda ToobaNo ratings yet

- Imholz Petrosino (2012)Document8 pagesImholz Petrosino (2012)Anthony PetrosinoNo ratings yet

- Japan's Education SystemDocument4 pagesJapan's Education Systemjessica.velo98No ratings yet

- Research Namen!Document3 pagesResearch Namen!Markjowen BasketballNo ratings yet

- Joining The ConversationDocument8 pagesJoining The ConversationMRSPIN12No ratings yet

- Fragoso Signature Assignment Inner City TeacherDocument15 pagesFragoso Signature Assignment Inner City Teacherapi-490973181No ratings yet

- Japan's National Curriculum Reforms: Focus On Integrated Curriculum ApproachDocument6 pagesJapan's National Curriculum Reforms: Focus On Integrated Curriculum ApproachHanifah RustamajiNo ratings yet

- Finland No Homework PolicyDocument7 pagesFinland No Homework Policynemyvasygud3100% (1)

- A Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanDocument14 pagesA Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanGuroGaniNo ratings yet

- Uploaded: 6 Jan 2021 at 3:50 PM Plagiarism: % Words: Checked WordsDocument17 pagesUploaded: 6 Jan 2021 at 3:50 PM Plagiarism: % Words: Checked Wordsaustinmc2003No ratings yet

- American EducationDocument62 pagesAmerican EducationN San100% (1)

- Secondary Education - Current Trends, International Issues - HISTORY OFDocument5 pagesSecondary Education - Current Trends, International Issues - HISTORY OFYasmeen JafferNo ratings yet

- Instruction B E684 Practicum LP 2Document8 pagesInstruction B E684 Practicum LP 2api-246209162No ratings yet

- How Much Homework Do Students in Japan GetDocument9 pagesHow Much Homework Do Students in Japan Getg1buk0h0fek2100% (1)

- Morgan - Final Equity StudyDocument36 pagesMorgan - Final Equity Studyapi-364187429No ratings yet

- Education Systems of The Philippines and PDFDocument24 pagesEducation Systems of The Philippines and PDFMichael Brian TorresNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Education SystemDocument4 pagesThe Japanese Education SystemNeil Trezley Sunico BalajadiaNo ratings yet

- GTVHDocument10 pagesGTVHNguyễn Đình ĐạtNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - USDocument8 pagesUnit 5 - US09- Đào Nguyễn Thị DHNN14A4HNNo ratings yet

- Mullins Library ResearchDocument5 pagesMullins Library Researchapi-464741970No ratings yet

- Why Do South Korean Students Study HardDocument10 pagesWhy Do South Korean Students Study HardJonathan JarvisNo ratings yet

- All N One Change Research PaperDocument18 pagesAll N One Change Research Paperapi-487598133No ratings yet

- BBC News - What Is The Key To A Successful Education SystemDocument3 pagesBBC News - What Is The Key To A Successful Education SystememiebaNo ratings yet

- Hurricane SandyDocument10 pagesHurricane Sandyapi-127539041No ratings yet

- Piraino Laura Instructionalrpt1Document5 pagesPiraino Laura Instructionalrpt1api-127539041No ratings yet

- Elm 533 - Piraino Laura Diaginstrrep-SaDocument9 pagesElm 533 - Piraino Laura Diaginstrrep-Saapi-127539041No ratings yet

- Eci 508 - Rosetta Stone - Final DraftDocument15 pagesEci 508 - Rosetta Stone - Final Draftapi-127539041No ratings yet

- Running Head: Silent Sustained Reading'S Effect On Reading Comprehension SkillsDocument14 pagesRunning Head: Silent Sustained Reading'S Effect On Reading Comprehension Skillsapi-127539041No ratings yet

- 5w Quarter 2Document2 pages5w Quarter 2api-127539041No ratings yet

- Reading Presentation To Faculty 2011-2012Document22 pagesReading Presentation To Faculty 2011-2012api-127539041No ratings yet

- Lesson Planning Form For Accessible Instruction - Calvin College Education ProgramDocument5 pagesLesson Planning Form For Accessible Instruction - Calvin College Education Programapi-300180062No ratings yet

- Maths Grd.8 Teachers Guide Senior Primary PDFDocument130 pagesMaths Grd.8 Teachers Guide Senior Primary PDFAdriane TingzonNo ratings yet

- 3 Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Consortium For Biomedical SciencesDocument2 pages3 Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Consortium For Biomedical SciencesTomson KosasihNo ratings yet

- Classroom Expectations: Introduction To Algebra Mr. JonesDocument8 pagesClassroom Expectations: Introduction To Algebra Mr. Jonesjennifer sampangNo ratings yet

- Gamification of Software TestingDocument6 pagesGamification of Software TestinggustavoparreiraaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Mentoring On Employee Performance of Selected Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Lagos State, NigeriaDocument13 pagesThe Effect of Mentoring On Employee Performance of Selected Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Lagos State, NigeriaAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- House UNIT - Lesson 1Document6 pagesHouse UNIT - Lesson 1Angélica SantiNo ratings yet

- AcknowledgementDocument7 pagesAcknowledgementnero_cakep100% (2)

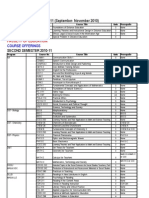

- Courseoffering 2 Ndsem 1011Document5 pagesCourseoffering 2 Ndsem 1011chelg24No ratings yet

- Top 5 Alternatives To Articulate Storyline 3 (October 2021) - SaaSworthy - Com2Document3 pagesTop 5 Alternatives To Articulate Storyline 3 (October 2021) - SaaSworthy - Com2شكيب حيمدNo ratings yet

- Modellaufgabenheft - English-Đã G PDocument93 pagesModellaufgabenheft - English-Đã G PThảo TrinhNo ratings yet

- 124 - Brm-First MDocument9 pages124 - Brm-First MPratik BhagatNo ratings yet

- Schroeder Et Al 2006Document7 pagesSchroeder Et Al 2006sharmaine17No ratings yet

- Human Resource Management Officer IIIDocument3 pagesHuman Resource Management Officer IIICarmela TolentinoNo ratings yet

- IEP GoalsDocument36 pagesIEP GoalsSree Laxmi AdibhatlaNo ratings yet

- 4.determines The Objectives and Structures of ReportsDocument23 pages4.determines The Objectives and Structures of ReportsJustineNo ratings yet

- Docentes MultimodalDocument579 pagesDocentes MultimodalCristian RizzoNo ratings yet

- Unit Test - Philo - 2nd Final With KeyDocument5 pagesUnit Test - Philo - 2nd Final With KeyZenaida CarbonelNo ratings yet

- Children Education Allowance Form WordDocument2 pagesChildren Education Allowance Form WordTechno WhatNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Study of Careers and Their HistoryDocument41 pagesIntroduction To The Study of Careers and Their HistoryFaiza OmarNo ratings yet

- Building A High Performance CultureDocument14 pagesBuilding A High Performance Culturenavinvijay2No ratings yet

- Audio Aural Learning ResourcesDocument6 pagesAudio Aural Learning Resourceskibet kennedyNo ratings yet

- Application For Study ScholarshipDocument2 pagesApplication For Study ScholarshipDevakalpa GhoseNo ratings yet

- Exam Unit 2 Part 2Document3 pagesExam Unit 2 Part 2Laia MajoralNo ratings yet

- ESDEP Vol0101ADocument64 pagesESDEP Vol0101Aaladinmf1100% (1)

- For Palarong Pambansa Only: Question For Athlete To Be Answered by The Parent: YES NO Remarks by ParentDocument1 pageFor Palarong Pambansa Only: Question For Athlete To Be Answered by The Parent: YES NO Remarks by ParentKeith RossNo ratings yet

- Effects of Extra-Curricular Activities On The Academic Performance of BCAS Junior High School This S.Y 2017-2018Document51 pagesEffects of Extra-Curricular Activities On The Academic Performance of BCAS Junior High School This S.Y 2017-2018Maxine MarundanNo ratings yet

Running Head: Comparative Education

Running Head: Comparative Education

Uploaded by

api-127539041Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Running Head: Comparative Education

Running Head: Comparative Education

Uploaded by

api-127539041Copyright:

Available Formats

Running Head: COMPARATIVE EDUCATION

Comparative Educational Study Devon C. Banks North Carolina State University May 2, 2010

2 Comparative Education The Extent of State Support for Education In the United States, approximately $1.1 trillion is currently being spent nationwide on education (U.S. Department of Education, 2010). The American education system is funded by the federal, state, and local governments. The state and local governments play a larger role in the education system than the federal government. Local school boards also play an active role in determining the outcome of their districts schools. The U.S. Department of Education reports that 89.5% of funds for primary and secondary education will come from non-federal foundations (U.S. Department of Education, 2010). The National Center for Education Statistics reports approximately $9,154 of unadjusted dollars being spent per pupil in elementary and secondary schools (National Center for Education, 2010). Although the United States allocates such a large sum of money toward pupils, American students often fall behind in comparison to students from other countries. CBS news reported on a study that found America as having one of the least effective education systems (Cosgrove-Mather, 2002). Japans education system has been somewhat modeled after the American education system, but also displays qualities of the European education system. Primary and lower secondary schools are compulsory, but higher secondary schooling is voluntary (Education in Japan, 2001). 3.5% of the gross domestic product is spent on Japans education system (Global Education Database, n.d.). In comparison with the United States, Japan spends only 9.5% of the government expenditure on education, and the total public education expenditure per pupil in Japan is 21.5% based on GDP per capita (Global Education Database, n.d.). Based on the UNESCO report, the United States devotes more of its economical profits toward education than Japan (Global Education Database, n.d.). The Peoples Republic of China has seen drastic reforms in recent years. The government has enacted stricter rules and regulations in order to increase the literacy rate, and give all citizens the

3 Comparative Education opportunity to attend public schools (Preus, 2007). Like Japan and America, China also instills a form of compulsory education. All citizens of the Peoples Republic of China must attend school for a minimum of nine years (Basic Education in China n.d.). The government provides both primary and secondary education for its citizens. As of 1999, 13% of the government expenditure was directed toward education (Global Education Database, n.d.). Also in 1999, 1.9% of the GDP was spent on education (Global Education Database, n.d.). There is a very small percentage of the education expenditure that is devoted to pre-primary schools. Majority of the education expenditure is intended for primary and secondary schools (Global Education Database, n.d.). Curriculum The curriculum for schools in the U.S. is also often determined by local school districts, and the local government. In Japan, China, and the United States, the basic core subjects are taught. The core subjects primarily taught in the U.S. are math, science, English, and history. Primary schools also offer classes such as physical education, art, and music. Much thought is given to the curriculum due to the No Child Left Behind Act (Preus, 2007). American primary schools have tough curricular standards that they must follow in order to perform sufficiently on yearly tests, and meet the yearly progress goals. Secondary schools also include the basic core subjects, but also allow students to take various elective courses. The elective classes can range from art, music, computers, graphic design, etc. The Japanese education system is often thought of to be quite rigorous compared to the American education system. Students spend more time in school and have fewer holidays, and also have high school entrance exams. Students have a brief winter and spring break, and only have one month of summer vacation (Education Japan, 2001). The Japanese curriculum focuses on core subjects such as math, science, Japanese, music, and art. Students also attend a moral education class at some point during the week. Most Japanese students have some sort of daily leadership duty each

4 Comparative Education day. These duties range from leading discussions, or making announcements. Students are responsible for cleaning and taking care of their school. Students in junior high often begin to take part in extracurricular activities, and begin studying for their high school entrance exam. Japanese students often score higher than American students on reading, math, and science tests (Education Japan, 2001). The Chinese curriculum has experienced many changes, and it still undergoing changes today. The Ministry of Education is mainly in charge of forming the curriculum and education standards. Kindergarten or Pre-Primary school is considered separate from primary school, and students may enter at the young age of three (Basic Education in China n.d.). In the early 1990s, Chinas primary and secondary schools adopted the idea of Teaching Scheme as a curriculum (Basic Education in China n.d.). This curriculum divided subjects into local-arranged subjects, and state-arranged subjects. Like Japan, China also includes moral education in their curriculum. Like the United States, local districts are able to adapt the curriculum to meet the needs of its constituents. Higher secondary schools also display some similarities to American schools as they are divided into school subjects, and optional classes. Chinese students are required to take mid-year, and end of year examinations. Primary school students are also tested on their language and reading abilities. Like the Japanese education system, China also has an expansive after-school education program. Students participating in the Chinese education system take part in a variety of clubs and cultural activities after the school day has ended (Basic Education in China n.d.). Standard Forms of Instruction American policies such as No Child Left Behind are moving American schools toward a form of centralized education (Preus, 2002). There is great emphasis placed on standardized testing in American schools, and many teachers only teach material that will be on the yearly tests. Teachers commonly use direct instruction in order to meet the test requirements. American teachers are also using more

5 Comparative Education technology in the classroom, as it becomes available. Research by Stigler and Hiebert (1999) found that American teachers use limited teaching methods. The lack of instructional methods in place in American schools could play a factor in the lower test scores and overall achievements of American students. Stigler and Hiebert (1999) also discussed the differences in math instruction in Japanese and American classrooms. American math teachers often use the overhead and boards more to describe in detail the ways to solve a math problem. Japanese teachers encourage students to form connections and relationships between the concepts (Seaman, 1999). In Japan, the teacher is predominately autonomous. Teachers and students work closely together which creates frequent interaction amongst peers. Japanese teachers have clear routines that are followed, and create goals to be reached by each student. Japanese teachers also place great emphasis on extra-curricular activities. Chinese classrooms often have a large number of students, and teachers lack many resources. Visual aids and lessons plans arent often used, and many teachers rely heavily on textbooks (Hanmer, 2001). There is also great emphasis on testing, which creates a lack of creativity in the schools. In China, The Ministry of Education creates syllabuses that are implemented in both primary and secondary schools. Teachers use these along with textbooks to reach national education standards (Basic Education in China n.d.). In order to meet the needs of all students, Chinese regulations regarding textbooks have slightly eased up. There is no longer one set of textbooks available for students, and teachers can now use many other resources in their classrooms (Preus, 2007). The relaxation on textbooks restrictions has allowed Chinese teachers to become more creative in their lesson planning. (Preus, 2007). Aims of the Education System CBS News reported on a UNICEF study that was aimed to discover the most effective education system among the worlds richest countries. Japan came in second place in terms of having the most effective education system, while the United States came in at the bottom of the list (Cosgrove-Mather,

6 Comparative Education 2002). Reports such as these raise doubts and concerns among American educators and school leaders. American schools are trying to raise reading, math, and science scores in order to compete with other countries. It appears that the main goal for leaders in Americas education system is to be considered number one. Teachers and other education leaders are also becoming increasingly concerned about the demands of globalization. Teachers are having to prepare their students for an interconnected, and very competitive global economy. Japan has one of the most successful and effective education systems in the world. Japan also has one of the highest adult literacy rates in the world. Modern Japanese schools aim to meet four key goals: legitimating the material, selecting and differentiating young people, transmitting cognitive knowledge, and acculturating. Each goal is used at a different point in a students career, and may not be taught in the same way in each school (Education Japan, 2001). As in American schools, public Japanese schools tend to follow the curriculum and national policies more closely than private schools. The Japanese view education as a way to instill cognitive development, and instill knowledge to help create successful, productive members of society (Education Japan, 2001). Like American schools, Japanese schools are trying to prepare their students for a competitive, global future. The Chinese education system has undergone dramatic reforms in the past fifty years. Government and education leaders have worked to increase the literacy rate, as well as provide compulsory education for Chinese citizens. Since 2002, China is working to provide compulsory education for both urban and rural citizens. Each year, more and more Chinese students are exempt from paying tuition and other fees related to their education. The Compulsory Education Law is also working to improve the quality of Chinese higher institutions (Basic Education in China n.d.). Preus (2007) reported that both Chinese and American governments recognize the importance in preparing

7 Comparative Education their students for a global economy. The Chinese hope that focusing more on creativity will help prepare their students, while Americans focus on accountability (Preus, 2007). All three educational systems are aiming to create successful, productive members of society. These countries are also working to increase and maintain the literacy rate. Within each educational system, each country is instilling the values and goals of that particular culture. As our world becomes increasingly connected, it will be harder to find and create jobs. Each education system has seen the vast changes being made across the globe, and realizes that students need to be competitive in order to achieve in our global economy.

8 Comparative Education References (2010). Basic Education in China. Retrieved Apr. 26, 2010, from Ministry of Education, Beijing, China. Web site: http://educationjapan.org/jguide/school_system.html.

(2001). Education Japan. Retrieved Apr. 19, 2010, from Education Japan. Web site: http://educationjapan.org/jguide/school_system.html.

(2009). Global Education Database. Retrieved Apr. 18, 2010, from United States Agency International Development, Arlington, VA. Web site: http://ged.eads.usaidallnet.gov/data/.

(2010). National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved Apr. 18, 2010, from National Center for Education Statistics, Washington, DC. Web site: http://nces.ed.gov/

(2010). U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved Apr. 24, 2010, from United States Department of Education, Washington, DC. Web site: http://www.ed.gov.

Cosgrove-Mather, B. (2002). Poor Marks for U.S. Education System. Retrieved Apr. 25, 2010, from CBS News, Geneva. Web site: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/11/26/world/main530872.shtml.

Hanmer, J. (2001). Chinese Teaching Methods. Retrieved May 1, 2010, from Project Janel, Madison, WI. Web site: http://projectjanel.org/china/methods.html.

Preus, B. (2007). Educational Trends in China And the United States: Proverbial Pendulum or Potential for Balance?. Phi Delta Kappan, 89(2), 115-118. Retrieved from Academic Search Premier database.

Seaman, R. (1999). Read This: The Teaching Gap. Retrieved May 1, 2010, from Mathematical Association of America, Washington, DC. Web site: http://www.maa.org/reviews/teachgap.html.

9 Comparative Education Stigler, J. W., & Hiebert, J. (1999). The Teaching Gap. New York, New York: Free Press.

Suzuki, M. J. (2000). Child-Rearing and Educational Practices in the United States and Japan: Comparative Perspectives. Hyogo University of Teacher Education Journal, 20(1), 177-186. Retrieved from database.

You might also like

- TEACHERS DOING RESEARCH - The Power of Action Through Inquiry, Second EditionDocument413 pagesTEACHERS DOING RESEARCH - The Power of Action Through Inquiry, Second EditionKhôi Vương Tấn MinhNo ratings yet

- CISCO Ccna 200-301 Practice Test (Exam Questions)Document2 pagesCISCO Ccna 200-301 Practice Test (Exam Questions)Lin TorvaldNo ratings yet

- Japanese Education in The 21st CenturyDocument359 pagesJapanese Education in The 21st Centuryshihabjamaan100% (1)

- Education Systems of The PhilippinesDocument24 pagesEducation Systems of The PhilippinesRD OseñaNo ratings yet

- TUTOROO Tutors Introductory Guide PDFDocument4 pagesTUTOROO Tutors Introductory Guide PDFJuan Sebastian Quintero BoteroNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanDocument14 pagesA Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanBien R. Gruba IIINo ratings yet

- Curruculum of Education in UsaDocument4 pagesCurruculum of Education in UsaSHAFIRANo ratings yet

- High-Stakes Schooling: What We Can Learn from Japan's Experiences with Testing, Accountability, and Education ReformFrom EverandHigh-Stakes Schooling: What We Can Learn from Japan's Experiences with Testing, Accountability, and Education ReformNo ratings yet

- Comparative Education HandoutDocument4 pagesComparative Education Handoutapi-318154963No ratings yet

- The Current Education System in The United States of AmericaDocument5 pagesThe Current Education System in The United States of Americadayna-um100% (1)

- Smast RullDocument10 pagesSmast Rullaraakimoto94No ratings yet

- Education in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskDocument21 pagesEducation in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskArnel V. BagayanaNo ratings yet

- Quantitative ResearchDocument104 pagesQuantitative ResearchMary Joy HubillaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum in JapanDocument20 pagesCurriculum in JapanVanessa NacarNo ratings yet

- COMPARATIVE-ANALYSIS South-Korea Japan ChinaDocument12 pagesCOMPARATIVE-ANALYSIS South-Korea Japan Chinaeduardo bragaisNo ratings yet

- Gcu 114 Japanese Education ReportDocument4 pagesGcu 114 Japanese Education Reportapi-423109495No ratings yet

- Curriculum in Japan: Learning Chinese CharactersDocument21 pagesCurriculum in Japan: Learning Chinese CharactersjolinaNo ratings yet

- Education in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskDocument21 pagesEducation in Japan: Superpower or A Nation at RiskMarvin OrbigoNo ratings yet

- Homework Policy in FinlandDocument4 pagesHomework Policy in Finlandafnaewonaoejmm100% (1)

- Curriculum in Japan: Presented To DR - Nadeem Presented by Sana AkramDocument18 pagesCurriculum in Japan: Presented To DR - Nadeem Presented by Sana AkramHina KaynatNo ratings yet

- Final Earning How To FixDocument2 pagesFinal Earning How To Fixapi-264385122No ratings yet

- Direct Instruction in MathematicsDocument29 pagesDirect Instruction in MathematicsJoyce LomibaoNo ratings yet

- Policy 3rdDocument19 pagesPolicy 3rdlemmademe204No ratings yet

- William Allan Kritsonis, PHDDocument11 pagesWilliam Allan Kritsonis, PHDWilliam Allan Kritsonis, PhD100% (1)

- American and Japanese EducationDocument13 pagesAmerican and Japanese Education1113892010100% (2)

- EducationDocument9 pagesEducationchsudheer291985No ratings yet

- 16.1 Education Around The World - Introduction To SocioDocument7 pages16.1 Education Around The World - Introduction To SocioМария РыжковаNo ratings yet

- Ap U S History Research Paper - Nishant Jain Rough DraftDocument20 pagesAp U S History Research Paper - Nishant Jain Rough Draftapi-319773246No ratings yet

- Critique On Educational Systems WorldwideDocument5 pagesCritique On Educational Systems WorldwideJohn Dominic RomeroNo ratings yet

- Educ 5010 Written Assigmt Unit 2Document6 pagesEduc 5010 Written Assigmt Unit 2Chris Emeka100% (1)

- What Happens During The School Day? Time Diaries From A National Sample of Elementary School TeachersDocument27 pagesWhat Happens During The School Day? Time Diaries From A National Sample of Elementary School TeachersSoledad VercellinoNo ratings yet

- Elementary School United States: Primary Education in The United States Children Pre-Kindergarten Secondary EducationDocument3 pagesElementary School United States: Primary Education in The United States Children Pre-Kindergarten Secondary Educationjaltamirano123No ratings yet

- Japan Country Case Study - Synthesis ReportDocument8 pagesJapan Country Case Study - Synthesis Reportapi-291966417No ratings yet

- Mem 646 - Comparative Educational Systmen, E - Education ApproachDocument30 pagesMem 646 - Comparative Educational Systmen, E - Education ApproachLengie Agustino - CobillaNo ratings yet

- Summer Reading LossDocument7 pagesSummer Reading Lossapi-259926624No ratings yet

- Position Argument - Uniting Education DraftDocument9 pagesPosition Argument - Uniting Education Draftapi-234201312No ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2pink_floydzNo ratings yet

- A Caring Errand 2: A Strategic Reading System for Content- Area Teachers and Future TeachersFrom EverandA Caring Errand 2: A Strategic Reading System for Content- Area Teachers and Future TeachersNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument10 pagesAnnotated BibliographyAlicia ElliottNo ratings yet

- Research Turnitin FinalDocument8 pagesResearch Turnitin Finalapi-559333472No ratings yet

- Unit: 4 Comparative Education in Developed Countries Education Theories and Practices in Japan: Education SystemDocument40 pagesUnit: 4 Comparative Education in Developed Countries Education Theories and Practices in Japan: Education SystemSyeda ToobaNo ratings yet

- Imholz Petrosino (2012)Document8 pagesImholz Petrosino (2012)Anthony PetrosinoNo ratings yet

- Japan's Education SystemDocument4 pagesJapan's Education Systemjessica.velo98No ratings yet

- Research Namen!Document3 pagesResearch Namen!Markjowen BasketballNo ratings yet

- Joining The ConversationDocument8 pagesJoining The ConversationMRSPIN12No ratings yet

- Fragoso Signature Assignment Inner City TeacherDocument15 pagesFragoso Signature Assignment Inner City Teacherapi-490973181No ratings yet

- Japan's National Curriculum Reforms: Focus On Integrated Curriculum ApproachDocument6 pagesJapan's National Curriculum Reforms: Focus On Integrated Curriculum ApproachHanifah RustamajiNo ratings yet

- Finland No Homework PolicyDocument7 pagesFinland No Homework Policynemyvasygud3100% (1)

- A Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanDocument14 pagesA Comparative Study of The Elementary Science Curriculum of Philippines and JapanGuroGaniNo ratings yet

- Uploaded: 6 Jan 2021 at 3:50 PM Plagiarism: % Words: Checked WordsDocument17 pagesUploaded: 6 Jan 2021 at 3:50 PM Plagiarism: % Words: Checked Wordsaustinmc2003No ratings yet

- American EducationDocument62 pagesAmerican EducationN San100% (1)

- Secondary Education - Current Trends, International Issues - HISTORY OFDocument5 pagesSecondary Education - Current Trends, International Issues - HISTORY OFYasmeen JafferNo ratings yet

- Instruction B E684 Practicum LP 2Document8 pagesInstruction B E684 Practicum LP 2api-246209162No ratings yet

- How Much Homework Do Students in Japan GetDocument9 pagesHow Much Homework Do Students in Japan Getg1buk0h0fek2100% (1)

- Morgan - Final Equity StudyDocument36 pagesMorgan - Final Equity Studyapi-364187429No ratings yet

- Education Systems of The Philippines and PDFDocument24 pagesEducation Systems of The Philippines and PDFMichael Brian TorresNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Education SystemDocument4 pagesThe Japanese Education SystemNeil Trezley Sunico BalajadiaNo ratings yet

- GTVHDocument10 pagesGTVHNguyễn Đình ĐạtNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - USDocument8 pagesUnit 5 - US09- Đào Nguyễn Thị DHNN14A4HNNo ratings yet

- Mullins Library ResearchDocument5 pagesMullins Library Researchapi-464741970No ratings yet

- Why Do South Korean Students Study HardDocument10 pagesWhy Do South Korean Students Study HardJonathan JarvisNo ratings yet

- All N One Change Research PaperDocument18 pagesAll N One Change Research Paperapi-487598133No ratings yet

- BBC News - What Is The Key To A Successful Education SystemDocument3 pagesBBC News - What Is The Key To A Successful Education SystememiebaNo ratings yet

- Hurricane SandyDocument10 pagesHurricane Sandyapi-127539041No ratings yet

- Piraino Laura Instructionalrpt1Document5 pagesPiraino Laura Instructionalrpt1api-127539041No ratings yet

- Elm 533 - Piraino Laura Diaginstrrep-SaDocument9 pagesElm 533 - Piraino Laura Diaginstrrep-Saapi-127539041No ratings yet

- Eci 508 - Rosetta Stone - Final DraftDocument15 pagesEci 508 - Rosetta Stone - Final Draftapi-127539041No ratings yet

- Running Head: Silent Sustained Reading'S Effect On Reading Comprehension SkillsDocument14 pagesRunning Head: Silent Sustained Reading'S Effect On Reading Comprehension Skillsapi-127539041No ratings yet

- 5w Quarter 2Document2 pages5w Quarter 2api-127539041No ratings yet

- Reading Presentation To Faculty 2011-2012Document22 pagesReading Presentation To Faculty 2011-2012api-127539041No ratings yet

- Lesson Planning Form For Accessible Instruction - Calvin College Education ProgramDocument5 pagesLesson Planning Form For Accessible Instruction - Calvin College Education Programapi-300180062No ratings yet

- Maths Grd.8 Teachers Guide Senior Primary PDFDocument130 pagesMaths Grd.8 Teachers Guide Senior Primary PDFAdriane TingzonNo ratings yet

- 3 Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Consortium For Biomedical SciencesDocument2 pages3 Annual Scientific Meeting of Indonesian Consortium For Biomedical SciencesTomson KosasihNo ratings yet

- Classroom Expectations: Introduction To Algebra Mr. JonesDocument8 pagesClassroom Expectations: Introduction To Algebra Mr. Jonesjennifer sampangNo ratings yet

- Gamification of Software TestingDocument6 pagesGamification of Software TestinggustavoparreiraaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Mentoring On Employee Performance of Selected Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Lagos State, NigeriaDocument13 pagesThe Effect of Mentoring On Employee Performance of Selected Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Lagos State, NigeriaAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- House UNIT - Lesson 1Document6 pagesHouse UNIT - Lesson 1Angélica SantiNo ratings yet

- AcknowledgementDocument7 pagesAcknowledgementnero_cakep100% (2)

- Courseoffering 2 Ndsem 1011Document5 pagesCourseoffering 2 Ndsem 1011chelg24No ratings yet

- Top 5 Alternatives To Articulate Storyline 3 (October 2021) - SaaSworthy - Com2Document3 pagesTop 5 Alternatives To Articulate Storyline 3 (October 2021) - SaaSworthy - Com2شكيب حيمدNo ratings yet

- Modellaufgabenheft - English-Đã G PDocument93 pagesModellaufgabenheft - English-Đã G PThảo TrinhNo ratings yet

- 124 - Brm-First MDocument9 pages124 - Brm-First MPratik BhagatNo ratings yet

- Schroeder Et Al 2006Document7 pagesSchroeder Et Al 2006sharmaine17No ratings yet

- Human Resource Management Officer IIIDocument3 pagesHuman Resource Management Officer IIICarmela TolentinoNo ratings yet

- IEP GoalsDocument36 pagesIEP GoalsSree Laxmi AdibhatlaNo ratings yet

- 4.determines The Objectives and Structures of ReportsDocument23 pages4.determines The Objectives and Structures of ReportsJustineNo ratings yet

- Docentes MultimodalDocument579 pagesDocentes MultimodalCristian RizzoNo ratings yet

- Unit Test - Philo - 2nd Final With KeyDocument5 pagesUnit Test - Philo - 2nd Final With KeyZenaida CarbonelNo ratings yet

- Children Education Allowance Form WordDocument2 pagesChildren Education Allowance Form WordTechno WhatNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Study of Careers and Their HistoryDocument41 pagesIntroduction To The Study of Careers and Their HistoryFaiza OmarNo ratings yet

- Building A High Performance CultureDocument14 pagesBuilding A High Performance Culturenavinvijay2No ratings yet

- Audio Aural Learning ResourcesDocument6 pagesAudio Aural Learning Resourceskibet kennedyNo ratings yet

- Application For Study ScholarshipDocument2 pagesApplication For Study ScholarshipDevakalpa GhoseNo ratings yet

- Exam Unit 2 Part 2Document3 pagesExam Unit 2 Part 2Laia MajoralNo ratings yet

- ESDEP Vol0101ADocument64 pagesESDEP Vol0101Aaladinmf1100% (1)

- For Palarong Pambansa Only: Question For Athlete To Be Answered by The Parent: YES NO Remarks by ParentDocument1 pageFor Palarong Pambansa Only: Question For Athlete To Be Answered by The Parent: YES NO Remarks by ParentKeith RossNo ratings yet

- Effects of Extra-Curricular Activities On The Academic Performance of BCAS Junior High School This S.Y 2017-2018Document51 pagesEffects of Extra-Curricular Activities On The Academic Performance of BCAS Junior High School This S.Y 2017-2018Maxine MarundanNo ratings yet