Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History of Seattle

History of Seattle

Uploaded by

Eric WirsingOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History of Seattle

History of Seattle

Uploaded by

Eric WirsingCopyright:

Available Formats

HISTORY OF SEATTLE

History of Pike Place

In 1907 the City Council designated the newly-planked Pike Place as a public market area where citizens could purchase fresh farm produce directly from local growers. On the first rainy Saturday it was open for business, August 17, 1907, those few farmers who came quickly sold everything they had brought. Only three months later, 120 farmers were selling from wagons lined up along Pike Place. By the end of the year a long narrow shed that contained 76 stalls for farmers and food vendors was being constructed to provide some protection from the weather. Rents ranged from $4 to $25 a month. By 1917 much of the Market we know today was constructed - the Economy Market, Corner Market, Sanitary Market, and the lower levels of the Main Market. The Market continued to grow and thrive during the 1920s and the Depression of the 1930s. In 1927, for instance, permits were issued to 627 farmers. During World War II, however, business at the Market began to decline. In 1941 the Sanitary Market was severely damaged by fire. With the internment of Japanese after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Market lost more than half its farmers. Following the war, the Market's decline continued. Many younger people decided not to return to farming. Farmland in the Duwamish and Green River Valleys became increasingly industrialized. Supermarket chains began to lure away customers. By the 1960s there were fewer than 100 farmers selling at the Market, and the number of customers was at an all-time low. -----------------------------------------------------------------------In 1963 consultant Donald Monson prepared a plan for Seattle's downtown that recommended the modernization of the Market area into the Pike Plaza. The development was to feature office towers, apartments, and parking structures, with a much smaller, updated market. When public outcry urged preservation of the Market, a revised urban renewal plan was drawn up. As these new plans were publicized, citizen opposition to the proposed demolition of the Market increased. Spearheaded by architect Victor Steinbrueck, a group called "Friends of the Market" was formed and worked with other citizen organizations to put the issue of the Market's future on the November, 1971 ballot. That day, 73,369 people voted to preserve the Market and 53,264 opposed the initiative measure. As a result, a seven-acre National Register of Historic Places and local Market Historical District was created to preserve the Market's core and a larger 22-acre area was established to provide opportunities for redevelopment and new construction. During the extensive ten-year restoration and redevelopment effort that followed, $50 million in public investment and $100 million in private money was channeled into the Market which is today a healthy, bustling community of merchants and residents.

Pike Place Market Description

The Pike Place Market downtown is the soul of Seattle, the oldest continually operating farmers market in the country, a civic resource saved from the wrecking ball of "progress" by public vote in 1971. But the market is no staid historic site preserved for tourists. It is a free-form funhouse of sights and smells and sounds and characters, a place where farmers and craftspeople display their wares and where residents and visitors alike jostle their way along crowded aisles and brick streets. Salmon fly through the air at fish vendors here (You may recognize the fish merchants that were featured in a Levis commercial tossing fish around), vegetable and flower displays are turned into works of art, countless eateries cook up tastes of the world, hillside vistas offer views of ferries and freighters passing on the bay below, street performers provide comic relief, and the original Starbucks coffee store still dispenses shitty espresso. Gawking is permitted, free of charge. The market is roughhewn poetry, always in motion. Just a few steps east of the market is the commercial heart of Seattle, a vivacious downtown community

Downtown Seattle

Up from the market is the commercial heart of Seattle, a lively downtown district of department stores, specialty shops, renovated historic theaters, hotels of every size, multiplex cinemas, espresso stands, restaurants and unexpected shopping experiences. City Centre's atrium includes a dazzling display of art glass, with work by Dale Chihuly and others from the internationally known Pilchuck School. Westlake Center's spacious exterior balconies overlook Westlake Park, the city's unofficial gathering place, where the paving tiles display a Northwest Indian design. The Washington State Convention & Trade Center is not the usual monster box consigned to the downtown hinterlands. This thoughtfully designed convention center sits atop Interstate 5, an ingenious solution that put it within walking distance of more than 5,000 hotel rooms and also linked it with Freeway Park, a peaceful urban oasis with a cascading waterfall. Seattle's downtown is enjoying a cultural rebirth. The Paramount and Fifth Avenue theaters have been restored even beyond their former glory, now hosting touring musicals and concerts. Benaroya Hall is under construction, soon to become home of the nationally-recognized Seattle Symphony. Wolfgang Puck's new pan-Asian restaurant, ObaChine, is a short step from Planet Hollywood, NikeTown and the country's first GameWorks by Sega, a multimedia entertainment experience. "Hammering Man," a mammoth sculpture, stands guard at the entrance to the Seattle Art Museum, a striking post-modern structure designed by famed architect Robert Venturi. A dramatic grand staircase leading to noteworthy permanent exhibits of art from Africa and Native American Northwest art, as well as traveling exhibits from around the globe. The Denny Regrade, also known as Belltown, is downtown's hippest area, a fastdeveloping scene of cutting edge clubs, boutiques, taverns, galleries and

restaurants, plus high-rise condominiums and apartments that have suddenly jump-started this long-neglected part of the city. Now, it's the 2218 and The Vogue, where Flying Fish meet the Crocodile Cafe.

History of Pioneer Square

In 1852 the spot that is known today as Pioneer Square was chosen by the first permanent white settlers as the location of their new city, the only flat area along the deep, protected harbor on Elliott Bay. The following year Henry Yesler began operating a steam sawmill near where Yesler Way and First Avenue South cross today. Logs from the wooded hillsides were skidded down to Yesler's sawmill and wharf. Business activity grew up near the mill, primarily along Commercial Street (now First Avenue South). On June 6, 1889, fire destroyed 25 blocks of mostly wood buildings in the City's central core. Fortunately, it occurred at a time when the local economy was strong, so rebuilding began almost immediately. Determined not to be vulnerable to another blaze, the City Council passed an ordinance that required buildings to be constructed in fire-resistant brick and stone. Because much of the city had been built on boggy, marshy ground, the area was filled, street levels were raised, and Seattle's Underground was created. -----------------------------------------------------------------------The architectural styles for the rebuilt district were modeled after the Richardsonian Romanesque buildings in Chicago and on the East Coast. Characteristics of this style include a heavy masonry base, use of the Roman arch, and different details on each floor. Almost the entire area had been rebuilt within two years. The brief construction period and the fact that a few architects designed most of the buildings resulted in a remarkably harmonious architectural character. Pioneer Square was in its heyday during the Alaska Gold Rush, which started in July, 1897, but began to decline soon after the turn of the century when the business district began to move northward along Second Avenue. Pioneer Square became a honky-tonk district of taverns, entertainment houses and bawdy hotels, and the area began a decline which lasted until the 1970s. Faced with virtually no pressure for redevelopment, the district's remarkable stand of turn-of-the-century buildings remained. By the 1960s a City plan called for the construction of a ring road around the downtown that would have required razing many old buildings. At about this time, architect Ralph Anderson began to restore buildings in the Pioneer Square neighborhood and moved his office there. The commercial potential of the district came to be recognized and architect Victor Steinbrueck conducted an inventory of the area's buildings. In May, 1970, with strong citizen support, Pioneer Square was established as Seattle's first preservation District and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. A District Review Board was created and guidelines were developed to preserve the area's architectural and historic character and to assure sensitive restoration of buildings for economically viable purposes. In 1973 a larger area was set aside to protect

Pioneer Square from traffic and development pressures associated with the Kingdome so that today the District encompasses approximately 88 acres.

Pioneer Square Description

The red brick buildings give warmth and character to Pioneer Square, Seattle's oldest neighborhood, now a historic district. These sturdy structures have endured boom and bust and renovation, somehow maintaining their grace through it all. This was the home of the original "Skid Road," a term born when timber was slid down Yesler Way to a steam-powered mill on the waterfront. Now, Pioneer Square is home to many of Seattle's art galleries, eateries and a hulking clamshell of a building called the Kingdome. More people now gather in this indoor stadium than lived in Seattle during Pioneer Square's heyday. Pioneer Square comes alive after dark. The historic district becomes the entertainment district, one of the city's liveliest collections of nightspots, from sports bars to hard rock taverns to romantic eateries. Cutthroats, bums, and thugs also stalk these nighted streets. When the sports fans and the club crowds depart, Pioneer Square reverts again to its leisurely pace. This is a prime browsing territory, with stores offering everything from expensive antiques to handmade toys, but especially books. Pioneer Square is rich in history and lore, examined in spirited detail on the popular Underground Tour which visits the eerie sunken storefronts of groundlevel Pioneer Square before the Great Fire of 1889. Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park is a small museum recalling the crazed days a century ago when rough-and-ready gold-seekers converged on Pioneer Square on their way to the Yukon. Smith Tower, which overlooks the square, was the tallest building west of the Mississippi when it was completed in 1914.

History of the International District

Seattle's International District, a neighborhood nestled south of downtown, is the cultural hub of the Asian American community. It rose not far from the waterfront, on reclaimed tideflats. During a gigantic city regrading project, completed in 1910, this muddy wasteland was filled in with earth, buildings were erected and the International District was born. It is the only area in the continental United States where Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, African Americans and Vietnamese settled together and built one neighborhood. In the beginning, sojourners from Asia -- mostly single men -- came by steamship and rail into the new port city, seeking refuge from poverty and war. They crowded into hotels, storefronts and employment halls which emerged near the railroad station and waterfront.

These men came when the city was young, and worked in the gambling places, laundries, hotels, restaurants, shops and canneries. They lived frugally, finding comfort in familiar surroundings, shrouded from the harsh discrimination outside. Later, when the laws permitted, they brought wives and relatives to make permanent their stake here. First, the Chinese built Chinatown, anchored along King Street. a gathering point, marketplace and home for laborers from the villages. An earlier Chinatown located near Second Avenue and South Washington Street, had been pushed aside by a major street extension in the 1920s. The Japanese developed a Nibonmachi or Japantown near Main Street, just north of the new Chinatown. The Japanese businesses -- restaurants, bathhouses, laundries, dry goods stores and markets -- vanished when their owners were herded off to internment camps during World War II. The Filipinos, the third Asian group to arrive, found their way into area hotels, seeking connections for work in the canneries. Some operated cafes, pool halls, barbershops and other small businesses. African Americans also settled in the area, establishing diners, groceries, taverns, tailor shops and night clubs. For many years, Seattle's after-hours jazz scene thrived on Jackson Street. After immigration quotas opened up in 1965, new Chinese arrivals, including families, began to repopulate area hotels. But the decision to build the Kingdome on the western edge of the District, coupled with the construction of the Interstate 5 freeway, created a threat to the area's survival. By the early 1970s, over half of the area's deteriorating hotels had shut down, and many longtime businesses had moved out of the area. During this time, young Chinese, Japanese and Filipino student activists, rallying under the banner of Asian American unity, led a fight to reclaim the area. They lobbied for low-income housing, set up bilingual social service programs, and formed a public corporation to preserve and renovate historic buildings. In 1973 the International Special Review District and Board was established by Ordinance (SMC 23.66.302) to promote, preserve and perpetuate the cultural, economic, historical, and otherwise beneficial qualities of the area, particularly the features derived from its Asian heritage. College-educated Asian American professionals --lawyers, accountants, doctors, dentists and social workers --set up offices in the former haunts of their parents and grandparents.

With public funds, hotels and streets were refurbished, new senior apartments were erected, and community-based service centers were established. In the 1980s, refugees from Vietnam opened restaurants, markets, and clothing and jewelry stores. Many set up shop in old buildings and newly constructed malls near 12th Avenue and South Jackson Street. Others opened in storefronts in the core of the International District. With the expansion of business activity, the eastern boundary of the District has moved beyond the freeway. An old community bustling with history and culture --now survives into the next generation.

Lake Washington & Central Area/South Seattle

The Lake Washington lakeside neighborhoods of Madison Park, Washington Park, Denny Blaine, Madrona, Leschi, Mount Baker and Lakewood/Seward Park are a mix of upscale and middle class residential areas that often seem to blend to-gether, with their thick trees, switchback streets and homes perched on hillsides. The nearby Washington Park Arboretum is a 200-acre symphony of color and calm, with its ever-changing vegetation, its meandering pathways and its lakeside vistas. The Japanese Garden, with a traditional Tea House, is a hushed place of inspiring serenity. The Central Area/South Seattle neighborhoods have long been the heart of the city's African American community. Entrepreneur William Grose was one of the community's pioneers, purchasing 12 acres of this rolling farmland in 1883 for $1,000 in gold. In the 1930s, the area began establishing its national reputation as a fertile ground for jazz and blues musicians who played in its clubs and stayed in its modest homes. Ray Charles, Quincy Jones, Jimi Hendrix and Ernestine Anderson have lived in this neighborhood. The Central Area today is an area of increasing economic activity, while still remaining the site of such crucial community institutions as the Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Center and Mount Zion Baptist Church. A homegrown campaign built the Martin Luther King, Jr. Park here, turning a vacant hillside into a 4.2-acre memorial to the slain civil rights leader. Its centerpiece is a 30-foot sculpture of African granite in a reflecting pool; tiles describe many of the important events and inspiring words of Dr. King's life, and display the names of the many contribu-tors to the memorial.

West Seattle & South King County

A dramatic high-rise bridge now leads from the city to West Seattle, but even this recent marvel of engineering does not seem to have truly connected this neighborhood to others in the city. West Seattle remains a world unto itself, with the feel akin to an island. Its considerable assets too often remain the sole province of proud West Seattle residents. Schmitz Park is a patch of wilderness in the city, a tall stand of undisturbed virgin trees. California Avenue is a busy commercial area. Colman Pool in Lincoln Park is a heated saltwater pool of Olympic dimensions. Alki Drive along the water in West Seattle has few, if any, equals in the city. It features stunning views of the downtown skyline and across Puget Sound. It has a sparkling sand beach that imparts a resort character and prompts an undeniable hunger for Spud Fish & Chips. The drive also includes the historic spot on Alki Beach where the first white settlers arrived in Seattle and spent the winter of 1851 before retreating to the less blustery site on Elliott Bay that became downtown. South of downtown lie vast reaches of industrial area and two airports, but also here is the remarkable new Museum of Flight beside the runway at Boeing Field. One of The Boeing Co.'s original buildings, the Red Barn, is part of the museum, as is a Great Gallery where a huge collection of aircraft hang from the glass ceiling. The Rainier Brewery, a local icon, is nearby, offering free tours (for everyone) and free tastes in the Mountain Room (for adults). Also south is the Rainier Valley, where Italian truck farmers first turned this fertile area into a place then called "Garlic Gulch." Many more spices are now employed in this multi-ethnic neighborhood, which also includes the Columbia City Historic District. South King County communities stretch along the shore of Puget Sound (Burien, Normandy Park, Des Moines) or at the south end of Lake Washington (Auburn, Kent, Tukwila). Sea-Tac International Airport, a city large enough to have its own crime rate, serves as the bustling gateway to "The Emerald City."

Bellevue & The East Side

What were once drowsy bedroom communities across Lake Washington slumber no more. Bellevue is the state's fifth largest city with its own impressive skyline, Kirkland has blossomed into a kind of youthful Sausalito on the lake and Redmond is the home of Microsoft, the international software giant. There are attractions galore in these growing Eastside communities, which can be reached across two different floating bridges (yes, floating bridges). Highway 520 (The Evergreen Point Bridge) skirts the University of Washington and the Arbore-tum on its way to Bellevue; the I-90 Bridge spans Mercer Island, whose sophisti-cated residents opt for an island lifestyle that couldn't be closer to the city.

Bellevue Square is one of the Northwest's most prestigious shopping malls (even including the Bellevue Art Museum) and the city's string of parks includes many jewels. Kirkland has managed to preserve much of its lakefront as parkland, despite many classy new developments, including Carillon Point, with its hint of the Riviera. Redmond's massive Marymoor Park includes a steeply banked velodrome for high-speed bicycle racing. Issaquah, along Interstate 90, treasures recreation at the beachfront Lake Sammamish State Park and on the popular hiking trails in the Cascades Mountain foothills known as the "Issaquah Alps." One of the more spectacular reasons to cross those floating bridges is found at Snoqualmie Falls, about 15 miles east of Bellevue just off I-90. The dramatic 268ft. torrent is almost as big a draw as the Salish Lodge, perched on a rock precipice beside the falls and the setting for "Twin Peaks," television's quirky series of the early '90s. Snoqualmie Pass nearby offers four winter ski areas for sports enthusiasts. To the north, discover Chateau Ste. Michelle Winery in Woodinville, an impressive French chateau with meticulously landscaped grounds where picnicking is all-but-mandatory. Across the road is Columbia Winery and Redhook Brewery, making this wine-and-brew country.

Seattles Waterfront

Saltwater and sea air evoke voyages and adventures that drew visitors to the Seattle Waterfront Neighborhood a century ago, when the docks resounded with cries of "Gold!" and this was the last stop in the States for throngs of prospectors heading north to Alaska. Now, the crowds on Alaskan Way may seek shorter voyages and tamer adventures, but they are drawn here, too. The Waterfront still excites the senses with its hurly-burly scene of bright lights and colorful banners, clanging bells on restored streetcars, large parks overlooking passing ships, ferry horns echoing off downtown skyscrapers, enticing aromas of salmon, crab and sourdough bread. But what seems, at first glance, a place of souvenirs and salt water taffy is a neighborhood in transition. One symbol of the transition is the new Harbor Steps, a 16,000-square-foot staircase so grand that it is, in fact, a park. This has turned out to be much more than just a pedestrian link between Western Avenue on the Waterfront and First Avenue and the Seattle Art Museum above. Harbor Steps has quickly become Seattle's version of Rome's Spanish Steps, a meeting place to pause and reflect and catch the sun, amid eight waterfall fountains, extensive plantings and inviting seating areas. The northern portion of the Waterfront is also being transformed. The Port of Seattle has turned a dilapidated cannery at Pier 69 into its stunning new headquarters. Pier 66 is now home to a state-of-the-art international conference center, Anthony's Pier 66 restaurant, a marina and a maritime museum (currently

under construction). Nearby, the bare wood deck of Pier 62/63 becomes one of America's most spectacular concert venues every summer, where top-flight artists perform amid an expansive setting of skyscrapers, boats and sunsets. Pier 56 is the gateway to Tillicum Village, a resplendently Northwest attraction which delighted 17 world leaders gathered for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in 1993. Visitors can cruise the same route across the Sound, enjoy the same alder-smoked salmon dinner and watch the magical stage produc-tion of Dance on the Wind, which recreates Northwest Indian traditions. And all this memorable evening requires is a ticket from Tillicum Village Tours. The Waterfront is home to The Seattle Aquarium, with its dramatic underwater dome room and its entertaining exhibits that range from a Pacific coral reef to cavorting sea otters. Next door is the Omnidome Theatre, where the huge screen thrills with hang-onto-your-seats features. Sailing adventures still begin on the Waterfront. Washington State Ferries depart from Pier 52, carrying passengers in cars, on bikes and on foot. The Bainbridge Island route is an easy half-hour jaunt to charming historic Winslow; Bremerton is a scenic hour away to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and its historic Navy ships. Argosy Tours at Pier 55 offers sightseeing cruises around the harbor and other Seattle waters. Bay Pavilion at Pier 57 houses a vintage carousel, dining and shops. Boats to Victoria, B.C., leave from Pier 48 (in summer) and Pier 69 (yearround). The sleek Spirit of Puget Sound sets off from Pier 70 on lunch and dinner cruises with tuneful live entertainment. Adventuresome visitors can even don a wetsuit and hitch a ride on a parasail cruising the Waterfront, a touch of Acapulco in the festive stew of this lively Seattle neighborhood.

NOTABLE PLACES IN SEATTLE

Downtown Alki Beach Lake Union Arboretum Woodland Park Zoo University of Washington Discovery Park Shilshole Bay Ballard Locks Port of Seattle Floating Bridge Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Park

You might also like

- Downtown Syracuse Walking TourDocument17 pagesDowntown Syracuse Walking TourJon0% (1)

- ZWEIHÄNDER - Chapter 4 - Professions (Professions)Document17 pagesZWEIHÄNDER - Chapter 4 - Professions (Professions)Eric WirsingNo ratings yet

- Starbucks Communications StrategyDocument23 pagesStarbucks Communications Strategyapi-284048334100% (1)

- Main Sreet Histories With Historic Photos and Addendum - CT - 3.26.12Document60 pagesMain Sreet Histories With Historic Photos and Addendum - CT - 3.26.12Arkansas Historic Preservation Program100% (1)

- BESM Utena Revolution PDFDocument8 pagesBESM Utena Revolution PDFEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- 6int 2005 Jun QDocument9 pages6int 2005 Jun Qapi-19836745No ratings yet

- Everythings An Argument NotesDocument4 pagesEverythings An Argument Notesjumurph100% (1)

- Beberapa Contoh Taman KotaDocument15 pagesBeberapa Contoh Taman KotaKarman SyamNo ratings yet

- Look Up, Oklahoma City! A Walking Tour of Oklahoma City, OklahomaFrom EverandLook Up, Oklahoma City! A Walking Tour of Oklahoma City, OklahomaNo ratings yet

- San Francisco's Civic Center The Heart of The City Beautiful MovementDocument7 pagesSan Francisco's Civic Center The Heart of The City Beautiful MovementAnonymous EvbW4o1U7No ratings yet

- Architectures in Boston (Nuntachat Mongkolchai)Document26 pagesArchitectures in Boston (Nuntachat Mongkolchai)JaJah NadineNo ratings yet

- A Walking Tour of New York City's Upper West SideFrom EverandA Walking Tour of New York City's Upper West SideRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- WSPark HistoryDocument8 pagesWSPark HistoryKatie EssenfeldNo ratings yet

- LandmarksDocument39 pagesLandmarkskasugagNo ratings yet

- New York City - Facts PPT FUN ACTIVITYDocument34 pagesNew York City - Facts PPT FUN ACTIVITYhqs17606No ratings yet

- Historic Home Tour: Pacific Grove'S 42 AnnualDocument16 pagesHistoric Home Tour: Pacific Grove'S 42 AnnualDarlene BillstromNo ratings yet

- Manhattan Moves Uptown: An Illustrated HistoryFrom EverandManhattan Moves Uptown: An Illustrated HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- The Meatpacking District: Neighborhood InfoDocument3 pagesThe Meatpacking District: Neighborhood InfoTiganila GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Look Up, San Francisco! A Walking Tour of the Financial DistrictFrom EverandLook Up, San Francisco! A Walking Tour of the Financial DistrictNo ratings yet

- Steps You Can Take To Get Used To Wearing A MaskDocument1 pageSteps You Can Take To Get Used To Wearing A MaskEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- Magic-User Spell List: DAROKIN Merchant Spells (Gaz-11) ALFHEIM Elves SpellsDocument20 pagesMagic-User Spell List: DAROKIN Merchant Spells (Gaz-11) ALFHEIM Elves SpellsEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- Mbaw 20anniversary v01Document26 pagesMbaw 20anniversary v01Eric WirsingNo ratings yet

- Morrowind Ini TweaksDocument3 pagesMorrowind Ini TweaksEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- Risus Trek - Star Trek ExeterDocument4 pagesRisus Trek - Star Trek ExeterEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- Swords & Spells v1.3 PDFDocument83 pagesSwords & Spells v1.3 PDFEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- RuneQuest Place #2 - Dread TowerDocument6 pagesRuneQuest Place #2 - Dread TowerEric Wirsing100% (1)

- Ashland Shakespeare Festival - 1-17Document1 pageAshland Shakespeare Festival - 1-17Eric WirsingNo ratings yet

- SW1 - The Secret of RedscarDocument8 pagesSW1 - The Secret of RedscarEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- And Mag I07 Fireforge Map PackDocument6 pagesAnd Mag I07 Fireforge Map PackEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- RQ NPC - The WhistlerDocument4 pagesRQ NPC - The WhistlerEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- Rack & Ruin #3Document3 pagesRack & Ruin #3Eric WirsingNo ratings yet

- RuneQuest NPC #5 - Zed NighthunterDocument3 pagesRuneQuest NPC #5 - Zed NighthunterEric Wirsing100% (1)

- RuneQuest NPC #4 - GorkDocument2 pagesRuneQuest NPC #4 - GorkEric WirsingNo ratings yet

- English File: Grammar, Vocabulary, and PronunciationDocument3 pagesEnglish File: Grammar, Vocabulary, and PronunciationEszter CsertánNo ratings yet

- India - Sri Lanka HVDC InterconnectionDocument2 pagesIndia - Sri Lanka HVDC InterconnectionsukhadiadarshanNo ratings yet

- The Unreveiled Secrets of The World of CakesDocument10 pagesThe Unreveiled Secrets of The World of CakesCake SquareNo ratings yet

- (Intro) The Digital Divide. The Internet and Social Inequality in International PerspectiveDocument31 pages(Intro) The Digital Divide. The Internet and Social Inequality in International PerspectiveChristopher HernándezNo ratings yet

- 2018 Dua Series Results & PointsDocument227 pages2018 Dua Series Results & PointsEL FuentesNo ratings yet

- Opening SalvoDocument6 pagesOpening SalvoMark James MarmolNo ratings yet

- Mission - List Codigos Commandos 2Document3 pagesMission - List Codigos Commandos 2Cristian Andres0% (1)

- St. Martin vs. LWVDocument2 pagesSt. Martin vs. LWVBaby T. Agcopra100% (5)

- FCCBDocument8 pagesFCCBRadha RampalliNo ratings yet

- Modul Berbicara 1Document49 pagesModul Berbicara 1Alif Satuhu100% (1)

- MTC Routes: Route StartDocument188 pagesMTC Routes: Route StartNikhil NandeeshNo ratings yet

- The Jet Volume 7 Number 4Document24 pagesThe Jet Volume 7 Number 4THE JETNo ratings yet

- Solutions To Chapter 6 Valuing StocksDocument20 pagesSolutions To Chapter 6 Valuing StocksSam TnNo ratings yet

- Economics PaperDocument4 pagesEconomics PaperAyesha KhanNo ratings yet

- I. Demographic Profile/Information Name: Theodore Robert Bundy (Ted Bundy) Age: 42Document5 pagesI. Demographic Profile/Information Name: Theodore Robert Bundy (Ted Bundy) Age: 42Maanne MandalNo ratings yet

- 3 MicroDocument4 pages3 MicroDumitraNo ratings yet

- Serres InterviewDocument9 pagesSerres InterviewhumblegeekNo ratings yet

- Start-Up Success Story PresentationDocument15 pagesStart-Up Success Story PresentationSamarth MittalNo ratings yet

- Top Picks - Axis-November2021Document79 pagesTop Picks - Axis-November2021Tejesh GoudNo ratings yet

- UNIT 8 Types of Punishment For Crimes RedactataDocument17 pagesUNIT 8 Types of Punishment For Crimes Redactataanna825020No ratings yet

- Practise QuestionaireDocument4 pagesPractise Questionaire8LYN LAWNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Monetary Policy:: A SummaryDocument43 pagesThe Effects of Monetary Policy:: A SummaryhumaidjafriNo ratings yet

- To Canadian Horse Defence Coalition Releases DraftDocument52 pagesTo Canadian Horse Defence Coalition Releases DraftHeather Clemenceau100% (1)

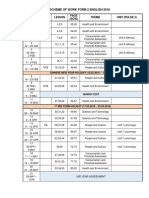

- Scheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Document2 pagesScheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Subramaniam Periannan100% (2)

- CAR BLGF Covid Response UpdateDocument8 pagesCAR BLGF Covid Response UpdatenormanNo ratings yet

- Building The Divided City - Class, Race and Housing in Inner London 1945-1997Document31 pagesBuilding The Divided City - Class, Race and Housing in Inner London 1945-1997Harold Carter100% (1)

- Week 9 All About GreeceDocument18 pagesWeek 9 All About GreeceNo OneNo ratings yet