Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Towards A Typology of Madrasas in West Bengal

Towards A Typology of Madrasas in West Bengal

Uploaded by

nikhilrpuriCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Proposal - New Islamic School in TorontoDocument9 pagesProposal - New Islamic School in Torontoarifin2484100% (4)

- Madrasah EducationDocument31 pagesMadrasah EducationAchmad Philip100% (2)

- Co Education and IslamDocument3 pagesCo Education and IslamHafiz M. Hammad Nomani100% (1)

- Madrassa EducationDocument21 pagesMadrassa EducationNameeb Itmaam0% (1)

- Abdurrahman Atçıl - Scholars and Sultans in The Early Modern Ottoman Empire-Cambridge University Press (2017)Document274 pagesAbdurrahman Atçıl - Scholars and Sultans in The Early Modern Ottoman Empire-Cambridge University Press (2017)huhubatNo ratings yet

- Hafiz ShiraziDocument14 pagesHafiz ShiraziMuzamil KhanNo ratings yet

- Islamic Schools: Millstone or MilestoneDocument190 pagesIslamic Schools: Millstone or MilestoneAsma AhmadiNo ratings yet

- 01 134 ENG V8 1 19 FormattedDocument18 pages01 134 ENG V8 1 19 Formattedayeshasalman689No ratings yet

- Al-Qur'An Education Park and Madrasah: Here Is Where Love Begins Group XIIDocument16 pagesAl-Qur'An Education Park and Madrasah: Here Is Where Love Begins Group XIIIrfan Noor SyabanaNo ratings yet

- Madrasa Report FinalDocument73 pagesMadrasa Report FinalmehztabNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature ReviewKiran JamilNo ratings yet

- Modernization of Madrasah Education in Bangladesh: A New Approach For Future DevelopmentDocument10 pagesModernization of Madrasah Education in Bangladesh: A New Approach For Future DevelopmentJibreel Kawure HusseinNo ratings yet

- Gunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida TejawianiDocument20 pagesGunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida Tejawianiindex PubNo ratings yet

- B.S Nishat EducationDocument10 pagesB.S Nishat Educationshabbir hussainNo ratings yet

- Gunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida Tejawiani: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10616837Document21 pagesGunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida Tejawiani: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10616837index PubNo ratings yet

- Reforming The Madrassah SystemDocument4 pagesReforming The Madrassah SystemMohammad Shujaul haq baigNo ratings yet

- Reforms According To Bangladesh Education Commission (Kudret e Khuda) 1974Document10 pagesReforms According To Bangladesh Education Commission (Kudret e Khuda) 1974Digonta AhmedNo ratings yet

- Amalan Sekolah Cemerlang Di Sekolah Berasrama Penuh Dan Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama: Satu PerbandinganDocument21 pagesAmalan Sekolah Cemerlang Di Sekolah Berasrama Penuh Dan Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama: Satu PerbandinganIkhsaan Subhan SNo ratings yet

- Implementation Management of Modern Education in Madrasah DiniyahDocument7 pagesImplementation Management of Modern Education in Madrasah DiniyahresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Business Model in Islamic Business Unit - FInal RevisionDocument22 pagesBusiness Model in Islamic Business Unit - FInal RevisionAdrian AriatinNo ratings yet

- Kedudukan Madrasah Dalam Sistem Pendidikan Nasional (Sisdiknas)Document17 pagesKedudukan Madrasah Dalam Sistem Pendidikan Nasional (Sisdiknas)Faqih Nur MuhammadNo ratings yet

- D R I F I E: Journal of Southwest Jiaotong UniversityDocument13 pagesD R I F I E: Journal of Southwest Jiaotong Universitydwi rizki amaliaNo ratings yet

- Research ProporsalDocument20 pagesResearch ProporsalWilfred MuthaliNo ratings yet

- 519 1036 1 SMDocument13 pages519 1036 1 SMdwi rizki amaliaNo ratings yet

- Serving Education With A DifferenceDocument4 pagesServing Education With A DifferenceSadaket MalikNo ratings yet

- Bus Term PaperDocument9 pagesBus Term Paperapi-442339817No ratings yet

- Developing Religious Identity: Assessing The Effects of Aliya Madrasahs On Muslim Students in BangladeshDocument12 pagesDeveloping Religious Identity: Assessing The Effects of Aliya Madrasahs On Muslim Students in BangladeshAnurag MediaNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of C.B.S.E and M.P. State Board Education PatternDocument8 pagesA Comparative Study of C.B.S.E and M.P. State Board Education PatternDawoodNo ratings yet

- Parents Open Letter To Mason School BoardDocument2 pagesParents Open Letter To Mason School BoardLansingStateJournalNo ratings yet

- Condition of Education in PakistanDocument52 pagesCondition of Education in PakistanKhan JanNo ratings yet

- Cluster Article 2Document21 pagesCluster Article 2Al Suhaimy Al MuariNo ratings yet

- 434 815 1 PB PDFDocument13 pages434 815 1 PB PDFmauhamad humaidyNo ratings yet

- WHC 4 F 30 F 4 C 4 D 469 DDocument74 pagesWHC 4 F 30 F 4 C 4 D 469 Drahman331No ratings yet

- Islamic Schools in South AfricaDocument2 pagesIslamic Schools in South AfricamuslimdirectoryNo ratings yet

- Social OrganizationDocument5 pagesSocial OrganizationhpajihparatNo ratings yet

- Jur Int 034 The Implementation 2013 CurriculumDocument12 pagesJur Int 034 The Implementation 2013 CurriculumSUTARMAN SUTARMANNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter IVDocument37 pages10 - Chapter IVsri_iasNo ratings yet

- Friday Bulletin 392Document8 pagesFriday Bulletin 392Wajid CockarNo ratings yet

- Islamic Religious Education: Case Study of A Madrasah in SingaporeDocument17 pagesIslamic Religious Education: Case Study of A Madrasah in SingaporeNoman HossainNo ratings yet

- Governance of Pesantren Salafiyah in Prophetic Leadership PerspectiveDocument11 pagesGovernance of Pesantren Salafiyah in Prophetic Leadership PerspectiveRoula AnnisaNo ratings yet

- Inggris 2 Last LastDocument8 pagesInggris 2 Last LastDaraNo ratings yet

- 016.sitiumi - Akhir SEMESTERStrategiPembelajaranPAI - Id.enDocument15 pages016.sitiumi - Akhir SEMESTERStrategiPembelajaranPAI - Id.enUmi FatchuljannahNo ratings yet

- Running Head: CONFLICT-EVALUATION 1Document6 pagesRunning Head: CONFLICT-EVALUATION 1BilalNo ratings yet

- University of Caloocan City Bachelor in Public AdministrationDocument8 pagesUniversity of Caloocan City Bachelor in Public AdministrationElsa Abaño De GuiaNo ratings yet

- Makalah KevinDocument10 pagesMakalah KevinSamsul MrfNo ratings yet

- The Role of Islamic Religious Education Teachers in Advocating For Muslim Minority Students in Denpasar, BaliDocument12 pagesThe Role of Islamic Religious Education Teachers in Advocating For Muslim Minority Students in Denpasar, BaliAndini Riswanda PutriNo ratings yet

- 6 Dr. Minakshi BiswalDocument11 pages6 Dr. Minakshi BiswalINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH STUDIESNo ratings yet

- Religious Education in Singapore: BackgroundDocument25 pagesReligious Education in Singapore: BackgroundAmiNo ratings yet

- Amrullah, Journal Manager, 1 Pengelolaan Pembiayaan (Inten, DKK)Document19 pagesAmrullah, Journal Manager, 1 Pengelolaan Pembiayaan (Inten, DKK)Ahmad BusyairiNo ratings yet

- Nur Hidayat - The Challenges of Madrasah at Global EraDocument17 pagesNur Hidayat - The Challenges of Madrasah at Global EraImam TurmidziNo ratings yet

- School Well-Being of Madrasah Tsanawiyah (MTS) and Madrasah Aliyah (Ma) in YogyakartaDocument14 pagesSchool Well-Being of Madrasah Tsanawiyah (MTS) and Madrasah Aliyah (Ma) in YogyakartaNicholasNo ratings yet

- Management of Social Entrepreneurship in Islamic Boarding SchoolsDocument11 pagesManagement of Social Entrepreneurship in Islamic Boarding SchoolsAuvaldo GeandraNo ratings yet

- Analisis Penerapan Kebijakan Pesantren Mu'adalahDocument29 pagesAnalisis Penerapan Kebijakan Pesantren Mu'adalahWahyudiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Sekolah UnggulanDocument14 pagesJurnal Sekolah UnggulanRiva NoviaNo ratings yet

- School Accreditation and Teacher Empowerment An Alabama CaseDocument19 pagesSchool Accreditation and Teacher Empowerment An Alabama CaseJoy ChristianNo ratings yet

- Disorientasi Pengembangan Intelektual Ptain?Document15 pagesDisorientasi Pengembangan Intelektual Ptain?Sekuy motobikeNo ratings yet

- Problem Statement of Ghost Schools in MusakhailDocument4 pagesProblem Statement of Ghost Schools in MusakhailHassan Khan Musa KhelNo ratings yet

- JPPPI v1 5 PDFDocument26 pagesJPPPI v1 5 PDFمحمد نور هشامNo ratings yet

- Smt. Chandibai Himathmal Mansukhani College. Ulhasnagar - 0 3Document17 pagesSmt. Chandibai Himathmal Mansukhani College. Ulhasnagar - 0 3Vinay KukrejaNo ratings yet

- MKT470 Research ProposalDocument4 pagesMKT470 Research ProposalHimesh ReshamiaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening The Tahfiz Study System in The Era of TheDocument12 pagesStrengthening The Tahfiz Study System in The Era of TherafarNo ratings yet

- Challenges Faced by Head Teachers in Dealing WithDocument4 pagesChallenges Faced by Head Teachers in Dealing WithEbuga Saduna JohnNo ratings yet

- Ekalavya Model Residential School For TRDocument11 pagesEkalavya Model Residential School For TRMujeebu Rahman VazhakkunnanNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Inclusive EducationDocument4 pagesBenefits of Inclusive EducationNasiif Abu SalsabeelNo ratings yet

- Dhaka Tribune 11 Oct '13 Page 11Document1 pageDhaka Tribune 11 Oct '13 Page 11nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Annotated Interview With Sashadhar Choudhury (ULFA)Document13 pagesAnnotated Interview With Sashadhar Choudhury (ULFA)nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- The Pioneer Delhi English Edition 10-09-2013 Page 9Document1 pageThe Pioneer Delhi English Edition 10-09-2013 Page 9nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Hizbul Mujahideen: A Martyred Militia?Document3 pagesHizbul Mujahideen: A Martyred Militia?nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Inside The Camps That Foment TerrorDocument1 pageInside The Camps That Foment TerrornikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- The Pakistani Madrassah and Terrorism: Made and Unmade Conclusions From The LiteratureDocument103 pagesThe Pakistani Madrassah and Terrorism: Made and Unmade Conclusions From The LiteraturenikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- There's No Safety in NumbersDocument1 pageThere's No Safety in NumbersnikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Cirebon Islamic School Was Founded in 2011 ALDocument1 pageCirebon Islamic School Was Founded in 2011 ALSD CIS KOTA CIREBON JAWA BARATNo ratings yet

- The Elements of Islamic MetaphysicsDocument222 pagesThe Elements of Islamic MetaphysicsS⸫Ḥ⸫R100% (1)

- Historical Foundations of Education by DRDocument5 pagesHistorical Foundations of Education by DRTotep Reyes50% (2)

- Islamic Values Ed-III Body PDFDocument133 pagesIslamic Values Ed-III Body PDFJona Pitogo ViadorNo ratings yet

- Mosque ManagementDocument127 pagesMosque ManagementAbdul Halim100% (1)

- Colonial and Post-Colonial Madrasa Policy On BengalDocument35 pagesColonial and Post-Colonial Madrasa Policy On BengalKhandkar Sahil RidwanNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument15 pagesResearch ArticleMalik AmarNo ratings yet

- Dualism SlideDocument45 pagesDualism SlideCekgu FaRd100% (1)

- Goodword Islamic Studies Grade 5Document3 pagesGoodword Islamic Studies Grade 5Long100% (1)

- Abdülbâsit El-Malatî'nin Eserlerinde Osmanlı TahayyülüDocument120 pagesAbdülbâsit El-Malatî'nin Eserlerinde Osmanlı TahayyülüyakupcivelekNo ratings yet

- DeobandDocument93 pagesDeobandpakhralNo ratings yet

- Islamic Studies ProjectDocument16 pagesIslamic Studies Projectearn moneyNo ratings yet

- Aqaaid e NizaamiyahDocument94 pagesAqaaid e NizaamiyahAbdul Qadir QadriNo ratings yet

- Filipino Muslims: Samira Gutoc Abdullah DimaporoDocument20 pagesFilipino Muslims: Samira Gutoc Abdullah DimaporoCharity Anne Camille PenalozaNo ratings yet

- Biography of Sheikh Abdul-Fattaaḥ Abu Ghuddah RA by Mufti Taqi DBDocument58 pagesBiography of Sheikh Abdul-Fattaaḥ Abu Ghuddah RA by Mufti Taqi DBAbdurrahman Al-MasumNo ratings yet

- Speech - Madrasah RoleDocument2 pagesSpeech - Madrasah RoleFitri80% (10)

- 29 PDFDocument7 pages29 PDFUbeyNo ratings yet

- A Reckoning With The Dars-I Nizāmī: by Mulla SaalehDocument29 pagesA Reckoning With The Dars-I Nizāmī: by Mulla SaalehMusab IqbalNo ratings yet

- Sachar Committee Recommendations-English PDFDocument13 pagesSachar Committee Recommendations-English PDFaqueelengNo ratings yet

- 100 Interesting and Motivating Stories From Sahih BukhariDocument304 pages100 Interesting and Motivating Stories From Sahih BukhariGogostopmNo ratings yet

- Inovasi Pembelajaran Pai Era Disrupsi Innovation 2018Document23 pagesInovasi Pembelajaran Pai Era Disrupsi Innovation 2018MuhammadZa'imNo ratings yet

- Senior Project Final DraftDocument13 pagesSenior Project Final Draftapi-496625709No ratings yet

- MamlukStudiesReview XIII-1 2009Document217 pagesMamlukStudiesReview XIII-1 2009shiraaaz100% (4)

- Bashir - Hanafi Legal Theory and Hadith - A Study of The Deobandi AttemptsDocument90 pagesBashir - Hanafi Legal Theory and Hadith - A Study of The Deobandi Attemptsjawadkhan2010No ratings yet

- Teachers Handbook 2004Document38 pagesTeachers Handbook 2004Ibrahima SakhoNo ratings yet

Towards A Typology of Madrasas in West Bengal

Towards A Typology of Madrasas in West Bengal

Uploaded by

nikhilrpuriOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Towards A Typology of Madrasas in West Bengal

Towards A Typology of Madrasas in West Bengal

Uploaded by

nikhilrpuriCopyright:

Available Formats

COMMENTARY

Towards a Typology of Madrasas in West Bengal

Nikhil Raymond Puri

states madrasa landscape. This article provides an elementary typology of madrasas in West Bengal, in turn, improving the legibility of the states modernisation efforts. Recognition-Seeking Madrasas

West Bengal is seen as a success story in the reform and modernisation of madrasas. What is the real picture in terms of the attitudes of and practices in the reforming and reluctant madrasas? What drives some madrasas to engage with reform of the syllabus and why are some others opposed?

Nikhil Raymond Puri (nikhilpuri@gmail.com) is a DPhil candidate at the University of Oxford, UK.

est Bengal is widely portrayed as a madrasa success story. Insofar as numerical indicators go, the state has managed to attract a signicant number of madrasas to its modernisation scheme. As of 2011, its reformed-to-unreformed ratio was about 1:1.6 (601 reformed madrasas versus about 950 unreformed madrasas). The state can also boast of the extent to which its madrasas have been modernised. The 601 madrasas that benet from the state support lay a heavy emphasis on secular subjects, following more or less the same curriculum as secular government schools. They also represent (through their student body) immense diversity of gender and religious afliation. About 65% of students in these madrasas are girls, and 13% are nonMuslims.1 Much of the states success has been attributed to the nancial incentives it makes available. In addition to state-sponsored teachers of secular subjects, madrasas partaking in West Bengals reform programmes are also given salaries for their religious teachers. But before highlighting the successes of West Bengals madrasa project, it is necessary to take a closer look at the

august 18, 2012

West Bengals madrasas fall into three major categories. The rst category consists of madrasas that are either unopposed to, or actively in pursuit of, recognition. Some madrasas model their curricula on that of the states recognised madrasas even before attaining recognition. By engaging in such acts of selfimposed modernisation, these madrasas try to convince the state of their determination, thereby hoping to expedite the recognition process. The Majerhat Pirdanga Bakhtiari Faizi Jalali Senior Madrasa in North 24 Parganas is a case in point. Established in 1980, this madrasa has voluntarily mimicked the state-imposed madrasa curriculum since its founding.2 A look at the subsequent evolution of the madrasas curriculum thus gives an indication of the extent to which the state has reformed the curricula of the (senior) madrasas under its jurisdiction.3 Initially, the madrasas curriculum, like that of the state, gave more weight to religious subjects. In 1989, the curriculum was modied, reducing the religious content, and introducing secular subjects such as science and geography. The 1,000-mark syllabus contained 350 marks of language study (150 marks Arabic, 100 marks Bengali,

vol xlviI no 33

EPW Economic & Political Weekly

22

COMMENTARY

and 100 marks English); 200 marks for the study of science (100 marks mathematics, 50 marks physical sciences and 50 marks life sciences); 50 marks for Islamic history; 50 marks for geography; and 350 marks devoted to the study of Islamic texts (100 marks Tafsir (Quranic commentary), 100 marks Hadith (prophetic traditions), 50 marks Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), 50 marks Usool (rulings on, and interpretation of, Islamic jurisprudence and prophetic traditions), and 50 marks Faraid (inheritance law). In 1995, the syllabus was further diluted in the case of this madrasa, voluntarily. Hundred marks of the Islamic texts were eliminated, and history was increased to 100 marks with the inclusion of 50 marks for modern history. In 2005, the Arabic component of the curriculum was reduced from 150 to 100 marks, leaving the overall religious component of the curriculum at just 350 out of 1,000 marks, excluding 100 marks for Arabic. While this gradual (but drastic) dilution of the once religion-heavy curriculum presents a major disincentive for many madrasas to opt for recognition, the Majerhat Pirdanga Bakhtiari Faizi Jalali Senior Madrasa voluntarily subjected itself to these changes in the hope of attaining recognition. This type of madrasa, which one may suitably call recognition-seeking, is not uncommon in West Bengal. The process of acquiring recognition involves a number of steps subsequent to the formal request. Once an application is submitted, the state inspects the madrasa to make sure it meets a number of prerequisites. These include requirements of syllabus, student strength, and infrastructure. But even when these minimum standards are met, the state is often slow in granting recognition. According to A K M Farhad, the recognition process can at times be characterised by red tape and nepotism.4 Knowing a politician or senior bureaucrat signicantly brightens ones prospects. Conversely, not having such connections could mean rejection in perpetuity. Thus, infrastructural inadequacies combined with inefciency (on the part of the state) have often kept willing madrasas from obtaining recognition. But unappealing

Economic & Political Weekly EPW

policies on the part of the state have also served to reduce the demand for recognition amongst recognition-seekers. Until 1997, the recognition process was quite straightforward. Recognition, once successfully obtained, led to immediate monetary rewards initially in the form of modest nancial support for the madrasa as a whole, and later, by way of salaries for its teachers. In 1997, however, the West Bengal state legislative assembly passed a bill whereby the teachers of a recognised madrasa became the responsibility of the state. A service commission was established to appoint teachers to madrasas through a centralised system. One reason why the Majerhat Pirdanga Bakhtiari Faizi Jalali Senior Madrasa is a senior one only in name is that the madrasas teachers fear being replaced by government-appointed substitutes. As Soharab Hossain, president of the West Bengal Board of Madrasah Education, explains, an attempt is underway to make an additional 200 madrasas in West Bengal recognised. These madrasas are willing to accept the recognised curriculum but are not willing to let the Madrasah Service Commission choose their teachers.5 Thus, the West Bengal School Service Commission Act of 1997 presents a critical juncture in the states madrasa reform efforts. Prior to its enactment, recognition-seeking madrasas were kept from obtaining recognition only by their own infrastructural shortcomings or the ineptitude of state ofcials. After 1997, however, madrasas formerly keen on accepting recognition were forced to recalibrate their position. Owing to the drastic shift in the nature (in qualitative terms) of support offered by the state, only one (senior) madrasa in West Bengal accepted recognition in the post1997 period. The unwillingness of (earlier recognition-ready) madrasas to accept recognition after 1997 stems from the increasingly aggressive and intrusive nature of the states efforts. Iman Ali, headmaster of the Aminpur Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti Senior Madrasa, has strong views on this matter: Many private madrasas are co-ed and follow the state-imposed syllabus, says Ali, but they still fail to get approval for recognition. The reason

vol xlviI no 33

for this refusal, Ali believes, is the governments allergy to senior madrasas. Given the relatively signicant (depending on ones vantage point) theological component of the senior madrasas, the government is much more willing to accept high madrasas, where religion is present only in the highly reduced form of Introduction to Islam.6 Opposed Madrasas The second category of madrasas in West Bengal consists of those elements that are fundamentally opposed to recognition, and can reasonably be called opposed madrasas. These khariji madrasas derive their very identity from the quality of existing and functioning outside the realm of government recognition. Mostly Deobandi, they are dened by a common ideology which precludes the possibility of accepting money from the state. But even within this category of madrasas, there exist different shades of opinion. Some opposed madrasas are willing to accept certain benets deriving from recognition (such as the states acknowledgement of the legitimacy of a madrasas degree) without accepting recognition per se. Others are unwilling to display any thappa (stamp) that bears the states authority. The Jamia Milia Madinatul Uloom in Bardhaman belongs to the rst type. Qazi Mohammad Yasin believes that khariji madrasas are to be dened, not by their curricula (more or less theology), but by their determination to remain outside the boundaries of the government.7 While this position ostensibly places Yasin amongst those wanting nothing to do with the state, he is more exible. Though Yasin holds that khariji madrasas are not allowed (as a matter of principle) to accept money from the state, he has actively sought state support of a different kind. Given its khariji status, students at Yasins madrasa do not receive degrees that are recognised by mainstream universities. Government madrasas, on the other hand, offer degrees that are considered equivalent to those of government-run secular schools, enabling their students to partake in higher education. In the hypothetical scenario where the state grants Yasins syllabus

23

august 18, 2012

COMMENTARY

equivalence (to that of a mainstream school) without any semblance of support, Yasin is likely to accept unhesitatingly. Yasins opposition thus rests on a double standard. He entertains the prospect of extracting specic state-derived benets, while simultaneously priding himself on his determination to function independently of the state. Another group of opposed madrasas, however, derives pride from remaining completely untainted by the states gaze. For them, any state support, be it nancial or otherwise, is completely unacceptable. Quari Fazlur Rahman of the Darul Quran Madrasa Azmatia represents this type of opposed madrasa. The thought of seeking recognition has neither occurred to Rahman in the past, nor is it likely to cross his mind in the future. With great pride he announces his position: We do not leave the (khariji) boundary within which we have been operating. It has been this way for a hundred years.8 Faqrul Islam Qasmi of the Jamia Qasim Ul Uloom is also resolutely opposed to recognition by the state. Qasmi conveys his position quite simply: The path towards recognition is unknown to me. All I know is this (the khariji way).9 What do the attitudes exhibited by the opposed madrasa portend for the states efforts at modernisation? The group, exemplied by Quari Fazlur Rahman and Faqrul Islam Qasmi, shows no signs of willingness to change. This madrasa is unlikely to move in any domain, instead representing the uncompromising opposition,

the end of the recognition continuum. The rst type of opposed madrasa shows more selectivity. Though rm in its opposition to recognition, this madrasa does acknowledge certain domains in which its opposition to state support may be relaxed. Selectively-opposed madrasas thus exhibit rigid opposition in some areas, and exibility in others. Both types of opposed madrasa, however, rmly oppose the acceptance of recognition. Fence-Sitting Madrasas The third category of madrasas in West Bengal is that of the fence-sitters. As the name suggests, fence-sitters consist of indecisive elements that remain on the fence because they could use the money (state support), but are unwilling to invite certain consequences associated with recognition (such as the dilution of their syllabi). This group of madrasas exhibits a willingness to become sarkari subject to certain conditions, and may jump to the recognised side of the fence as and when the state alters the terms of its engagement. These schools teach primarily deeni (religious) subjects and do not give much weight to secular subjects like mathematics, English and science. It is important to recognise that most schools in this category would rather approach a Muslim-run non-governmental organisation (NGO) or other source of funding before approaching the state (if the necessity should arise). While these fence-sitters are legitimately khariji in

that they oppose the states support, they differ from opposed madrasas in one very important respect. Opposed madrasas derive part of their identity from their autonomy vis--vis the state. Fence-sitters, on the other hand, are only opposed to certain specic terms of the recognition package. As these terms change, so may the intensity of their opposition. Their willingness to accept state support depends on both the quantitative (magnitude of economic incentives) and qualitative (degree of interference by the state) nature of this support. A K Abdul Khaleque of the Al-Jamiatul Faruqiyah Azharul Uloom in Bardhaman is a fence-sitter. He has a clear sense of the advantages accompanying recognition, and would readily trade his current salary of Rs 3,000 per month for a government salary of Rs 18,000 per month. Before doing so, however, he wants an assurance that his acceptance of state support will not lead to the dilution of his syllabus. We want the benets of recognition, says Khaleque, but not by selling our beliefs.10 Mohammad Shahidul Qadri of the Madrasa Hussainiya Ghausiya is also discerning of what lies across the fence. Like Khaleque, he is willing to cross the fence if it means he can enjoy nancial support without having to endure interference. If the madrasa modernisation programme in West Bengal functioned more as it does in other states, says Qadri, I would be inclined to accept recognition.11

REVIEW OF URBAN AFFAIRS

July 28, 2012

Making Ends Meet: Youth Enterprise at the Rural-Urban Intersections Subaltern Urbanisation in India Rejuvenating Indias Small Towns The North-East Map of Delhi Protesting Publics in Indian Cities: The 2006 Sealing Drive and Delhis Traders Enumerating the Semi-Visible: The Politics of Regularising Delhis Unauthorised Colonies Stephen Young, Craig Jeffrey Eric Denis, Partha Mukhopadhyay, Marie-Hlne Zrah Kalpana Sharma Duncan McDuie-Ra Diya Mehra Anna Zimmer

For copies write to: Circulation Manager, Economic and Political Weekly, 320-321, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013. email: circulation@epw.in

24

august 18, 2012 vol xlviI no 33

EPW Economic & Political Weekly

COMMENTARY

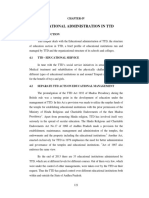

these madrasas present ideal candidates Locating the Dividing Line In order to establish the dividing line for recognition. Many, though not all, of between khariji and sarkari madrasas, it West Bengals 601 recognised madrasas is necessary to locate the fence on which correspond to this type. The remaining the fence-sitters are perched. This can recognised madrasas would qualify as be done by determining the common fence-sitters today, but applied for state denominator dening all madrasas that support at a time when recognition had refuse recognition. As is evident from a very different meaning. Such situations the preceding discussion, the opposition where recognition-seekers by yesterdays of khariji madrasas to recognition is standards become would be fence-sitters driven by a number of factors, each of by todays standards suggest that often which seems sufcient (but not neces- times a madrasas concerns are shaped sary). Some heads of madrasas are un- by events following the recognition deciwilling to afliate with a curriculum sion. In the 1970s, for instance, the govthat runs counter to their imaan (beliefs), ernment supported madrasas without others are additionally hesitant to re- modifying the contents of their syllabi. ceive money from the state, and yet oth- Naturally, dilution of the syllabus was ers are unwilling to bear the stamp of a concern unknown to many madrasas the state on their sleeve. But at any given that accepted recognition at the time.12 time, only one such concern is shared by Amongst those madrasas that are opall khariji madrasas (since those madra- posed to recognition, the uncompromissas that do not share this concern are ex- ingly-opposed madrasas represent the pected to cross the fence and accept rec- other extreme of the madrasa landscape. ognition). This common concern denes They thrive on their khariji status and the fence. Though this fence may be resist every opportunity to partake in characterised by periods of relative stasis, state-initiated modernisation. The other it is equally capable of movement in species in the opposed category is the response to changes in the terms of the selectively-opposed madrasa. It shows no states support. For most of West Bengals willingness to accept recognition per se, history in madrasa modernisation, the but is still open to the possibility of fence has moved gently as the conse- obtaining specic benets accomquences of accepting recognition evolved panying recognition. The differences be(in consonance with the gradual dilution tween the fence-sitter and the selectivelyof the senior madrasas religious curric- opposed madrasa, though subtle, are ulum). The critical juncture presented important. The fence-sitter is open to in 1997, on the other hand, induced a the prospect of accepting recognition, more noticeable shift in the fence. The but momentarily exhibits discontent increased intrusiveness of the state in with its details. The selectively-opposed 1997 led to a displacement of the common madrasa, on the other hand, is blind to concern (amongst khariji madrasas) the option of recognition. It may seek from dilution of the Figure: Classification of Madrasas in West Bengal The fence syllabus to a loss of say in teacher selec1: Recognition-seekers 3: Fence-sitters 2b: Uncompromisingly opposed tion. This displaceRecognised Madrasas Khariji Madrasas ment was in turn ac2a: Selectively opposed companied by a leftward shift of the fence (with respect to benets that form part of the states recits position in the gure). ognition package, but it does so upholding its independent status and avoidConclusions ing the undesirable prex sarkari. To summarise, the madrasa landscape The fence-sitters position is: I would acin West Bengal looks very much like the cept recognition if so and so conditions one depicted in the gure. Recognition- were satised. The selectively-opposed seeking madrasas constitute one end of madrasa sees less need for exchange: I the spectrum. Voluntarily diluting their denitely will not accept recognition, curricula to mirror that of the state, but the state ought to provide such

Economic & Political Weekly EPW

and such regardless as a right rather than a reward.13 While opposing madrasas are characterised by immobility, there is more movement between the other two types of madrasas fence-sitters and recognitionseekers. This movement depends on the position of the fence. A leftward shift of the fence (signifying an increasingly intrusive recognition package) will likely cause more recognition-seekers to join the club of fence-sitters. Similarly, a rightward shift of the fence (representing more amenable terms of support) will prompt many fence-sitters to accept recognition. The state needs to appreciate this context and position the fence accordingly. Any respectable standard of success demands that the modernisation scheme is able to absorb willing entrants while simultaneously attracting at least some madrasas that are not already modern.

Notes

1 Soharab Hossain (president, West Bengal Board of Madrasah Education, Kolkata), interviewed by author on 20 July 2009. 2 Hossain Mohammad Ebrahim Laskar and Mohammad Khabir Hossain (teachers, Majerhat Pirdanga Bakhtiari Faizi Jalali Senior Madrasa, North 24 Parganas), interviewed by author, on 1 October 2009. 3 West Bengals reformed madrasas can be classied under three categories according to grade level and religious character: junior high, high and senior madrasas. Amongst these, senior madrasas are most committed (in terms of curriculum content) to religious instruction. 4 A K M Farhad (teacher, Ghutiarisharif SSGMNS Senior Madrasa, South 24 Parganas), interviewed by author, 27 August 2009. 5 Interviewed by author, 20 July 2009. 6 Iman Ali (headmaster, Aminpur Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti Senior Madrasa, North 24 Parganas), interviewed by author, 1 October 2009. 7 Interviewed by author, 18 August 2009. 8 Interviewed by author, 3 October 2009. 9 Interviewed by author, 30 September 2009. 10 A K Abdul Khaleque (headmaster, Al-Jamiatul Faruqiyah Azharul Uloom, Bardhaman), interviewed by author, 18 August 2009. 11 Interviewed by author, 17 August. 12 The same cannot be said of the Service Commission legislation passed in 1997 (which gives the state control over teacher appointment in the madrasa) since it only applies to madrasas accepting recognition after its enactment. 13 Individuals running madrasas of the selectivelyopposed type hold the view that the state should provide them certain benets unconditionally. For instance, Qazi Mohammad Yasin suggests that acceptance of his madrasas degree (by universities) should not be contingent on his acceptance of recognition. Rather, he considers this benet a baseline provision for which all educational institutions (whether governmental or private, religious or secular) should qualify.

august 18, 2012

vol xlviI no 33

25

You might also like

- Proposal - New Islamic School in TorontoDocument9 pagesProposal - New Islamic School in Torontoarifin2484100% (4)

- Madrasah EducationDocument31 pagesMadrasah EducationAchmad Philip100% (2)

- Co Education and IslamDocument3 pagesCo Education and IslamHafiz M. Hammad Nomani100% (1)

- Madrassa EducationDocument21 pagesMadrassa EducationNameeb Itmaam0% (1)

- Abdurrahman Atçıl - Scholars and Sultans in The Early Modern Ottoman Empire-Cambridge University Press (2017)Document274 pagesAbdurrahman Atçıl - Scholars and Sultans in The Early Modern Ottoman Empire-Cambridge University Press (2017)huhubatNo ratings yet

- Hafiz ShiraziDocument14 pagesHafiz ShiraziMuzamil KhanNo ratings yet

- Islamic Schools: Millstone or MilestoneDocument190 pagesIslamic Schools: Millstone or MilestoneAsma AhmadiNo ratings yet

- 01 134 ENG V8 1 19 FormattedDocument18 pages01 134 ENG V8 1 19 Formattedayeshasalman689No ratings yet

- Al-Qur'An Education Park and Madrasah: Here Is Where Love Begins Group XIIDocument16 pagesAl-Qur'An Education Park and Madrasah: Here Is Where Love Begins Group XIIIrfan Noor SyabanaNo ratings yet

- Madrasa Report FinalDocument73 pagesMadrasa Report FinalmehztabNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature ReviewKiran JamilNo ratings yet

- Modernization of Madrasah Education in Bangladesh: A New Approach For Future DevelopmentDocument10 pagesModernization of Madrasah Education in Bangladesh: A New Approach For Future DevelopmentJibreel Kawure HusseinNo ratings yet

- Gunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida TejawianiDocument20 pagesGunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida Tejawianiindex PubNo ratings yet

- B.S Nishat EducationDocument10 pagesB.S Nishat Educationshabbir hussainNo ratings yet

- Gunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida Tejawiani: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10616837Document21 pagesGunawan, Iim Wasliman, Hanafiah and Ida Tejawiani: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10616837index PubNo ratings yet

- Reforming The Madrassah SystemDocument4 pagesReforming The Madrassah SystemMohammad Shujaul haq baigNo ratings yet

- Reforms According To Bangladesh Education Commission (Kudret e Khuda) 1974Document10 pagesReforms According To Bangladesh Education Commission (Kudret e Khuda) 1974Digonta AhmedNo ratings yet

- Amalan Sekolah Cemerlang Di Sekolah Berasrama Penuh Dan Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama: Satu PerbandinganDocument21 pagesAmalan Sekolah Cemerlang Di Sekolah Berasrama Penuh Dan Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama: Satu PerbandinganIkhsaan Subhan SNo ratings yet

- Implementation Management of Modern Education in Madrasah DiniyahDocument7 pagesImplementation Management of Modern Education in Madrasah DiniyahresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Business Model in Islamic Business Unit - FInal RevisionDocument22 pagesBusiness Model in Islamic Business Unit - FInal RevisionAdrian AriatinNo ratings yet

- Kedudukan Madrasah Dalam Sistem Pendidikan Nasional (Sisdiknas)Document17 pagesKedudukan Madrasah Dalam Sistem Pendidikan Nasional (Sisdiknas)Faqih Nur MuhammadNo ratings yet

- D R I F I E: Journal of Southwest Jiaotong UniversityDocument13 pagesD R I F I E: Journal of Southwest Jiaotong Universitydwi rizki amaliaNo ratings yet

- Research ProporsalDocument20 pagesResearch ProporsalWilfred MuthaliNo ratings yet

- 519 1036 1 SMDocument13 pages519 1036 1 SMdwi rizki amaliaNo ratings yet

- Serving Education With A DifferenceDocument4 pagesServing Education With A DifferenceSadaket MalikNo ratings yet

- Bus Term PaperDocument9 pagesBus Term Paperapi-442339817No ratings yet

- Developing Religious Identity: Assessing The Effects of Aliya Madrasahs On Muslim Students in BangladeshDocument12 pagesDeveloping Religious Identity: Assessing The Effects of Aliya Madrasahs On Muslim Students in BangladeshAnurag MediaNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of C.B.S.E and M.P. State Board Education PatternDocument8 pagesA Comparative Study of C.B.S.E and M.P. State Board Education PatternDawoodNo ratings yet

- Parents Open Letter To Mason School BoardDocument2 pagesParents Open Letter To Mason School BoardLansingStateJournalNo ratings yet

- Condition of Education in PakistanDocument52 pagesCondition of Education in PakistanKhan JanNo ratings yet

- Cluster Article 2Document21 pagesCluster Article 2Al Suhaimy Al MuariNo ratings yet

- 434 815 1 PB PDFDocument13 pages434 815 1 PB PDFmauhamad humaidyNo ratings yet

- WHC 4 F 30 F 4 C 4 D 469 DDocument74 pagesWHC 4 F 30 F 4 C 4 D 469 Drahman331No ratings yet

- Islamic Schools in South AfricaDocument2 pagesIslamic Schools in South AfricamuslimdirectoryNo ratings yet

- Social OrganizationDocument5 pagesSocial OrganizationhpajihparatNo ratings yet

- Jur Int 034 The Implementation 2013 CurriculumDocument12 pagesJur Int 034 The Implementation 2013 CurriculumSUTARMAN SUTARMANNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter IVDocument37 pages10 - Chapter IVsri_iasNo ratings yet

- Friday Bulletin 392Document8 pagesFriday Bulletin 392Wajid CockarNo ratings yet

- Islamic Religious Education: Case Study of A Madrasah in SingaporeDocument17 pagesIslamic Religious Education: Case Study of A Madrasah in SingaporeNoman HossainNo ratings yet

- Governance of Pesantren Salafiyah in Prophetic Leadership PerspectiveDocument11 pagesGovernance of Pesantren Salafiyah in Prophetic Leadership PerspectiveRoula AnnisaNo ratings yet

- Inggris 2 Last LastDocument8 pagesInggris 2 Last LastDaraNo ratings yet

- 016.sitiumi - Akhir SEMESTERStrategiPembelajaranPAI - Id.enDocument15 pages016.sitiumi - Akhir SEMESTERStrategiPembelajaranPAI - Id.enUmi FatchuljannahNo ratings yet

- Running Head: CONFLICT-EVALUATION 1Document6 pagesRunning Head: CONFLICT-EVALUATION 1BilalNo ratings yet

- University of Caloocan City Bachelor in Public AdministrationDocument8 pagesUniversity of Caloocan City Bachelor in Public AdministrationElsa Abaño De GuiaNo ratings yet

- Makalah KevinDocument10 pagesMakalah KevinSamsul MrfNo ratings yet

- The Role of Islamic Religious Education Teachers in Advocating For Muslim Minority Students in Denpasar, BaliDocument12 pagesThe Role of Islamic Religious Education Teachers in Advocating For Muslim Minority Students in Denpasar, BaliAndini Riswanda PutriNo ratings yet

- 6 Dr. Minakshi BiswalDocument11 pages6 Dr. Minakshi BiswalINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH STUDIESNo ratings yet

- Religious Education in Singapore: BackgroundDocument25 pagesReligious Education in Singapore: BackgroundAmiNo ratings yet

- Amrullah, Journal Manager, 1 Pengelolaan Pembiayaan (Inten, DKK)Document19 pagesAmrullah, Journal Manager, 1 Pengelolaan Pembiayaan (Inten, DKK)Ahmad BusyairiNo ratings yet

- Nur Hidayat - The Challenges of Madrasah at Global EraDocument17 pagesNur Hidayat - The Challenges of Madrasah at Global EraImam TurmidziNo ratings yet

- School Well-Being of Madrasah Tsanawiyah (MTS) and Madrasah Aliyah (Ma) in YogyakartaDocument14 pagesSchool Well-Being of Madrasah Tsanawiyah (MTS) and Madrasah Aliyah (Ma) in YogyakartaNicholasNo ratings yet

- Management of Social Entrepreneurship in Islamic Boarding SchoolsDocument11 pagesManagement of Social Entrepreneurship in Islamic Boarding SchoolsAuvaldo GeandraNo ratings yet

- Analisis Penerapan Kebijakan Pesantren Mu'adalahDocument29 pagesAnalisis Penerapan Kebijakan Pesantren Mu'adalahWahyudiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Sekolah UnggulanDocument14 pagesJurnal Sekolah UnggulanRiva NoviaNo ratings yet

- School Accreditation and Teacher Empowerment An Alabama CaseDocument19 pagesSchool Accreditation and Teacher Empowerment An Alabama CaseJoy ChristianNo ratings yet

- Disorientasi Pengembangan Intelektual Ptain?Document15 pagesDisorientasi Pengembangan Intelektual Ptain?Sekuy motobikeNo ratings yet

- Problem Statement of Ghost Schools in MusakhailDocument4 pagesProblem Statement of Ghost Schools in MusakhailHassan Khan Musa KhelNo ratings yet

- JPPPI v1 5 PDFDocument26 pagesJPPPI v1 5 PDFمحمد نور هشامNo ratings yet

- Smt. Chandibai Himathmal Mansukhani College. Ulhasnagar - 0 3Document17 pagesSmt. Chandibai Himathmal Mansukhani College. Ulhasnagar - 0 3Vinay KukrejaNo ratings yet

- MKT470 Research ProposalDocument4 pagesMKT470 Research ProposalHimesh ReshamiaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening The Tahfiz Study System in The Era of TheDocument12 pagesStrengthening The Tahfiz Study System in The Era of TherafarNo ratings yet

- Challenges Faced by Head Teachers in Dealing WithDocument4 pagesChallenges Faced by Head Teachers in Dealing WithEbuga Saduna JohnNo ratings yet

- Ekalavya Model Residential School For TRDocument11 pagesEkalavya Model Residential School For TRMujeebu Rahman VazhakkunnanNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Inclusive EducationDocument4 pagesBenefits of Inclusive EducationNasiif Abu SalsabeelNo ratings yet

- Dhaka Tribune 11 Oct '13 Page 11Document1 pageDhaka Tribune 11 Oct '13 Page 11nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Annotated Interview With Sashadhar Choudhury (ULFA)Document13 pagesAnnotated Interview With Sashadhar Choudhury (ULFA)nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- The Pioneer Delhi English Edition 10-09-2013 Page 9Document1 pageThe Pioneer Delhi English Edition 10-09-2013 Page 9nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Hizbul Mujahideen: A Martyred Militia?Document3 pagesHizbul Mujahideen: A Martyred Militia?nikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Inside The Camps That Foment TerrorDocument1 pageInside The Camps That Foment TerrornikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- The Pakistani Madrassah and Terrorism: Made and Unmade Conclusions From The LiteratureDocument103 pagesThe Pakistani Madrassah and Terrorism: Made and Unmade Conclusions From The LiteraturenikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- There's No Safety in NumbersDocument1 pageThere's No Safety in NumbersnikhilrpuriNo ratings yet

- Cirebon Islamic School Was Founded in 2011 ALDocument1 pageCirebon Islamic School Was Founded in 2011 ALSD CIS KOTA CIREBON JAWA BARATNo ratings yet

- The Elements of Islamic MetaphysicsDocument222 pagesThe Elements of Islamic MetaphysicsS⸫Ḥ⸫R100% (1)

- Historical Foundations of Education by DRDocument5 pagesHistorical Foundations of Education by DRTotep Reyes50% (2)

- Islamic Values Ed-III Body PDFDocument133 pagesIslamic Values Ed-III Body PDFJona Pitogo ViadorNo ratings yet

- Mosque ManagementDocument127 pagesMosque ManagementAbdul Halim100% (1)

- Colonial and Post-Colonial Madrasa Policy On BengalDocument35 pagesColonial and Post-Colonial Madrasa Policy On BengalKhandkar Sahil RidwanNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument15 pagesResearch ArticleMalik AmarNo ratings yet

- Dualism SlideDocument45 pagesDualism SlideCekgu FaRd100% (1)

- Goodword Islamic Studies Grade 5Document3 pagesGoodword Islamic Studies Grade 5Long100% (1)

- Abdülbâsit El-Malatî'nin Eserlerinde Osmanlı TahayyülüDocument120 pagesAbdülbâsit El-Malatî'nin Eserlerinde Osmanlı TahayyülüyakupcivelekNo ratings yet

- DeobandDocument93 pagesDeobandpakhralNo ratings yet

- Islamic Studies ProjectDocument16 pagesIslamic Studies Projectearn moneyNo ratings yet

- Aqaaid e NizaamiyahDocument94 pagesAqaaid e NizaamiyahAbdul Qadir QadriNo ratings yet

- Filipino Muslims: Samira Gutoc Abdullah DimaporoDocument20 pagesFilipino Muslims: Samira Gutoc Abdullah DimaporoCharity Anne Camille PenalozaNo ratings yet

- Biography of Sheikh Abdul-Fattaaḥ Abu Ghuddah RA by Mufti Taqi DBDocument58 pagesBiography of Sheikh Abdul-Fattaaḥ Abu Ghuddah RA by Mufti Taqi DBAbdurrahman Al-MasumNo ratings yet

- Speech - Madrasah RoleDocument2 pagesSpeech - Madrasah RoleFitri80% (10)

- 29 PDFDocument7 pages29 PDFUbeyNo ratings yet

- A Reckoning With The Dars-I Nizāmī: by Mulla SaalehDocument29 pagesA Reckoning With The Dars-I Nizāmī: by Mulla SaalehMusab IqbalNo ratings yet

- Sachar Committee Recommendations-English PDFDocument13 pagesSachar Committee Recommendations-English PDFaqueelengNo ratings yet

- 100 Interesting and Motivating Stories From Sahih BukhariDocument304 pages100 Interesting and Motivating Stories From Sahih BukhariGogostopmNo ratings yet

- Inovasi Pembelajaran Pai Era Disrupsi Innovation 2018Document23 pagesInovasi Pembelajaran Pai Era Disrupsi Innovation 2018MuhammadZa'imNo ratings yet

- Senior Project Final DraftDocument13 pagesSenior Project Final Draftapi-496625709No ratings yet

- MamlukStudiesReview XIII-1 2009Document217 pagesMamlukStudiesReview XIII-1 2009shiraaaz100% (4)

- Bashir - Hanafi Legal Theory and Hadith - A Study of The Deobandi AttemptsDocument90 pagesBashir - Hanafi Legal Theory and Hadith - A Study of The Deobandi Attemptsjawadkhan2010No ratings yet

- Teachers Handbook 2004Document38 pagesTeachers Handbook 2004Ibrahima SakhoNo ratings yet