Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SNATS Paper v1 3: Vocal Pedagogy For Performers of Medieval Music: An Introduction To Current Research & Writing

SNATS Paper v1 3: Vocal Pedagogy For Performers of Medieval Music: An Introduction To Current Research & Writing

Uploaded by

Wolodymyr SmishkewychOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SNATS Paper v1 3: Vocal Pedagogy For Performers of Medieval Music: An Introduction To Current Research & Writing

SNATS Paper v1 3: Vocal Pedagogy For Performers of Medieval Music: An Introduction To Current Research & Writing

Uploaded by

Wolodymyr SmishkewychCopyright:

Available Formats

Wolodymyr Smishkewych Jacobs School of Music Indiana University (Bloomington)

Vocal pedagogy for performers of medieval music: Restructuring the way we think and talk about teaching voice * In this presentation, I will address the * lack of a specific pedagogical method for vocal technique in performing solo medieval vocal music. The time constraints of this presentation and the space limitation of a symposium paper cannot do justice to an aspect of our discipline that requires a much more thorough treatment, which I hope to address in future research. I nonetheless hope this morning to bring up important questions and core issues that implicate those of us who teach voice specifically to performers of repertoire of approximately 1400 and before, to those of us who perform this repertoire regularly. I also hope that the discussion generated will lead to more research work in this area and attention to it in our voice curricula. I will my observations about the following topics as they pertain to the teaching of this repertoire: * * How the concepts of performance authenticity and performers authenticitybeing true to what we know, what we can do, and how we communicate with listenersaffect the teaching and learning of singing; * How the tools & vocabulary used in teaching may affect the way students think about performance and vocal production; as an extension of this, * How the vocabulary that dominates the discussion of vocal technique and pedagogy de facto excludes repertoires before the 16th century by virtue of the imagery-language often employed; * * Additionally, I will discuss some challenges we may encounter as teachers of this pre1400 repertoire within the context of being style-polyvalent voice teachers, such as the effects of changing sound aesthetics and of the recording industry on our students; * Ill also emphasize the need to address vocal technique and pedagogy in a systematic, curricular way within early music programs in North America, and the need to cement the relationship between voice departments and early music teachers & performers; * And Ill wrap up with an outline of my observations on some common vocal problems that present themselves in students singing medieval music, the likely causes and possible resolutions thereof, which I will deal with in future research. * During the mid-1980s, Oxfords Early Music magazine invited writers to discuss what was termed The great authenticity debate. Authors wrote on a number of topics, tempers flared, accusations flew and lids flipped on musicologists, performers and critics. One short but a propos letter was written by the notable Barbara Thornton, who passed away a decade ago this year. In her letter The Singers View, which you have reproduced for you in the handout, Thornton wrote the following: The most dramatic problem of all for the performer of early music is that he cannot fall back on years of training, begun at an early age, which should have prepared him for his role as a professional musician. Most specialist early music singers I know have had to hide the fact that they were interested in early music from their singing teachers at some point, since they knew there would be no support or guidance from that direction.

Wolodymyr Smishkewych Jacobs School of Music Indiana University (Bloomington)

Instead they struggled to synthesize a serviceable technique, from what seem to be the 'healthy' aspects of modern technique and their ideas and impressions of what is required of them in the various historical repertories. The singer of early music suffers greatly under these circumstances. I do not believe that a singer can be struggling to reconstruct in his imagination a lost musical tradition while he is still learning the art of voice production. A singer learns through personal contact, through his senses, no matter what his intellect is trying to tell him. Singers need teachers who can actually do what it is they will one day be doing themselves. They need to be steeped in the world of a given repertory, in a tradition. Then, in the course of a lifetime, they may learn how to produce a specific and appropriate aesthetic response to the demands of the repertory. Early music vocal teaching will have to be greatly improved and demonstrate a lot more dedication before any real gain in authenticity on stage will be noticeable. Thornton summed up and also brought to light a number of salient points that reflect on the training of all singers. However, they affect singers specializing in various repertoires in different ways. Singers specializing in repertoire of the last 2-3 centuries have the greatest advantage in terms of Thorntons first point *, simply because the standard curriculum of vocal learning is geared towards this later repertoire. We are fortunate that in many respects the landscape has changed for the second point * : there is now much greater support from many quarters and from many teachers for performers of what is termed early repertoire. There are more departments specializing in historical performance and more singing teachers who are themselves successful performers of these repertoires. However, even amongst students and performers of early music repertoires there * still exists the concept that the Default setting is still non-Early Music: why else would so many singers within early music departments still say things such as: are you doing an Early Music Voice degree or one in Regular voice? But, although this may at times be frustrating, it might be less helpful, at this point in time, to take apart institutions or even conventions than it is to generate * an awareness of these distinctions and the biases that both engender them and that arise from them. So, lets take a look at these distinctions and biases one by one. * * Even with a diversity of conceptual approaches, vocal pedagogy is almost exclusively dominated by a vocabulary that implies certain historical and stylistic values. I maintain that this vocabulary, dominated by * language originating in 18th-19th century bel canto pedagogy, creates problems for performing repertoires before 1400. More often than not, * this pedagogical vocabulary and style impliesperhaps unwittinglythe superiority of a later performance style over earlier ones. This occurs * even in the face of increased scientific information that should promise some sort of objective way of gauging vocal health for performers and teachers. As a result, the student is, in Thorntons words, often forced to patch together a serviceable technique combining the healthy aspects of modern vocal technique with what they have learned about historical performance and style.1 * However, an approach based on * superimposition of style over technique has its problems, which stem from the following: In the training of singers at most universities and conservatories in North America, the * voice lessonsand where available, vocal pedagogy coursesquite often demonstrate a synergy and integration specifically with

Wolodymyr Smishkewych Jacobs School of Music Indiana University (Bloomington)

vocal repertoire and aesthetics from the late 18th century onwards. We find illustrative examples in the books of famous pedagogy writers that show examples from Puccini and Verdi, not Bernard de Ventadorn or Hildegard. A plethora * of bel canto based terminology and imagery-vocabulary regarding timbre, breath management, onset, phonation, sonance, phrasing or other vocal qualities * abounds. On the other hand, * one of the hallmarks of later twentieth and current vocal pedagogy research is that * scientific measurement (both quantitative * and qualitative) is the standard by which we should measure and address voice teaching. I maintain that this last goalthe scientific description of vocal use, quality and functionis a sound benchmark by which teachers of any styles and repertoire can benefit greatly, if we choose to apply it uniformly and as a principle. * My reason for stating this is that, * though we may utilize scientific-approach knowledge in our pedagogy but in order to integrate it in our teaching continue to employ language that is based in and attached to the aesthetics and tradition of 18th century and later bel canto, * we are sending the message to our students that while on the surface we may support their choices (or even our own) to perform repertoire from before the bel canto period, we really believe the aesthetics of bel canto and later to be the default or true manner of singing by which all other singing should be judged, stylistically and, by extension, technically. * I propose instead that * teachers of singers of medieval repertoire modify their use of technical & descriptive vocabulary to truly reflect a full synthesis of scientifically acquired information with what we are now transmitting as a recuperated stylistic tradition, i.e., performance practice. It is, on the one hand, more clear in technical terms, * than if we rely solely on medieval treatises that mention singing or deal with it exclusively: earlier sources could only discuss empirically the technical aspects of singing; they did not have access to scientific research as we do today, though they did benefit from a constant personal contact with masters and from an oral transmission of aesthetics and sound quality goals. But those us performing and teaching today have the * ability to choose our teaching language and embody our technical concepts with examples from the right repertoire. We also do our students service by * using clear language, and whenever possible, utilizing terms and imagery vocabulary taken from students own words, thereby reinforcing their own habits when these are deemed to be headed in the right direction. * I also wish to emphasize the need for todays voice * teachers of medieval music performers to master the technical and anatomical knowledge of the vocal instrument and be trained specifically in vocal pedagogy. In the same breath I wish to reiterate my * caution to all voice teachers not to assume that a mastery of vocal pedagogy or anatomy should imply using a teaching vocabulary that is slanted towards the bel canto-style tradition and historical period. At the very least, such terminology is not at all helpful to singers of earlier repertoires. Rather, it * reinforces the idea that were are simply superimposing a style onto singing technique, as opposed to what should be * our actual goal: allowing healthy vocal function to occur with non-style specific imagery and instructions, while singing vocal repertoire of a given period. * One step in * addressing the extent to which students and thus future teachers are versed in the technical aspects of voice teaching is * by the degree to which vocal pedagogy is taught. * A quick look at vocal pedagogy requirements (outside of voice lessons) at music schools with an Early Music of Historical Performance Department that grants degrees in Voice, * shows that in the USA and Canada, none of the schools granting early music voice degrees or diplomas require a vocal pedagogy course in their curriculum, although at every

Wolodymyr Smishkewych Jacobs School of Music Indiana University (Bloomington)

one of these institutions, such an option is available as an elective or as a minor field study. I propose that one way in which we can prevent a situation where future teachers of early vocal repertoires are untrained in the technical and pedagogical aspects of singing, is by requiring vocal pedagogy courses in their degree curricula, particularly since it would only require the addition of an already existing course to the curriculum. (table with schools) * * * Challenges will arise for most voice teachers, in having to teach multiple style repertoires outside of a specialized department. Especially in our post-modern age, we have come to believe that such a quality is perfectly normal and desirable. It wasnt always the case, of courseteachers have specialized in particular styles and repertoires for centuries without being labeled as incompetent, but rather as masters of their styles. Students would come to such a teacher because he or she performs the repertoire they are drawn to or wish to perform. * However, often (as is the case in institutions where we may be the sole voice teacher, or one of only a few) students are unable to choose the voice teacher they would wish to have, for any number of circumstances. (This is part of the way that universities that teach music are set up to operate.) In these cases, we must be ready to serve as the factotum for these students. They may wish to sing music of different styles: different within a students performing history, and often different from what we ourselves may enjoy singing or even listening to. This is a challenge for all voice teachers, and I believe the model we generate from addressing the problems of teaching pre-1400 repertoire can help us better cope with the challenge. * Additionally, one of the main challenges in these times of ubiquitous technology, digital media, and millions of recordings, is that aspiring singers are bombarded by vocal models, and often choose to style their own singing after a particular musician. * The early-music recording boom has been both a wonderful proving ground for ideas and sounds and a minefield for singers trying to find develop their vocal sound. * However, the aesthetics of a desirable vocal sound have changed since the early days of the EM revival: while the monks of Silos may have gone gold, their vocal technique and phrasing is not emulated in many of the leading ensembles that currently perform and record chant or medieval song. Instead, * aesthetic ideals for todays professional medieval repertoire singers align with a more robust singing tradition, one that places a high emphasis on the words and their delivery and meaning but also on a consistent timbral quality and phrasing. For this reason, * the teacher of medieval music singers should be actively involved in guiding the aesthetic formation of the student inasmuch as their performing choices reflect their aesthetic influences. A judicious teacher helps students constantly raise the bar on singing aesthetics, whatever the musical or historical style. * I have mentioned that as teachers of students performing this repertoire our goal should be to stay away from the concept of superimposing style over technique, and rather teaching technique without a bias for a particular style. However, I have also noted that at many institutions, voice teachers must be ready to fulfill a multifaceted role and serve all students well. This includes dealing in practical terms with the fact that at this point in history, many

Wolodymyr Smishkewych Jacobs School of Music Indiana University (Bloomington)

singers within the university or conservatory system have already undergone a lifelong style-exposure to music of the 18th century and later. They have, as a matter of course, superimposedin practice, conflatedtheir knowledge of historical style over the technique they thus associate with healthy singing. As a result, there are several technical issues that tend to arise as a result of this combination or superimposition. I will not be able to present today the details of my research, which includes noting some of problems that can be observed in singers studying or performing pre-1400 repertoire, as well as some strategies for troubleshooting these problems. However, I will outline the topics into which these observations are grouped. This list is far from comprehensive; in fact it is only superficial. My future research will deal with the specifics in greater detail and expand upon the pedagogical aspects of these observations. * Breath management issues related to phrasing & execution of extended melismatic passages (i.e. troubadour song, organum duplum & triplum voices, long chant lines); * Challenge of attaining a balanced, dynamic non-tremulous clarity of tone (vs. restrictive, held-larynx static tone) Notice I stay away from the two buzzwords, vibrato and straight tone; Diction, historical pronunciations & hyperfunctional of buccopharyngeal & lingual action: the difference between what the singer imagines they (should) hear vs. what the listener hears; * Voice classification and pitch level for medieval repertoire & repercussions of poorly selected pitch levels on singers sustained vocal production; this ties in directly with the * choices made when singing in vocal ensembles: singing is generally more sustained and higher sustained range (i.e. tessitura) can be a cause for further problems. (An eternal problem for all voice teachers!) As with any topic pertaining to teaching philosophies, the * issues I have presented this morning touch the core of what we feel our purpose is as voice teachers. What is at the heart of our pedagogy, what is it that we set out to doand set out to avoid? We may agree that, as a firm principle, we all have an unwritten Hippocratic maxim: Above all do no (vocal) harm. It follows, then, that we must lead our students to avoid all vocal harm, through guidance andif we canby example, in the music that speaks most to their hearts as well as ours.

Barbara Thornton, The Singers View. Early Music, Vol. 12, No. 4. (Nov., 1984), pp. 523-524.

You might also like

- 5e Ngss Lesson Planning Template 0Document3 pages5e Ngss Lesson Planning Template 0api-244472956No ratings yet

- Secondary Choral CurriculumDocument25 pagesSecondary Choral CurriculumrodicamedoNo ratings yet

- Improvisation An Essential Element of Musical ProficiencyDocument7 pagesImprovisation An Essential Element of Musical Proficiencyx100% (1)

- Edtpa Task 1 - Part eDocument7 pagesEdtpa Task 1 - Part eapi-273801384No ratings yet

- Lean Launchpad Educators Teaching Handbook January 2013 SmallDocument113 pagesLean Launchpad Educators Teaching Handbook January 2013 SmallAleksandar TasevNo ratings yet

- Ubd AnimalsDocument4 pagesUbd AnimalsKathlene Joyce LacorteNo ratings yet

- Modernizing Academic Teaching and Research in Business and EconomicsDocument192 pagesModernizing Academic Teaching and Research in Business and EconomicsKarim HashemNo ratings yet

- BIO 325 Syllabus Fall 2014Document6 pagesBIO 325 Syllabus Fall 2014Jacobsen RichardNo ratings yet

- Economics Course OutlineDocument5 pagesEconomics Course OutlineSaud ManzarNo ratings yet

- Tajweed Syllabus Student Handout PDFDocument1 pageTajweed Syllabus Student Handout PDFSingganuNo ratings yet

- 3mini CourseproposalsDocument7 pages3mini Courseproposalsapi-331290571No ratings yet

- Parncutt (2007) - Can Researchers Help ArtistsDocument25 pagesParncutt (2007) - Can Researchers Help ArtistsLuis Varela CarrizoNo ratings yet

- Task 2Document2 pagesTask 2NATALIA ALBALADEJO MARTÍNEZNo ratings yet

- Mantle Hood Bi MusicalityDocument6 pagesMantle Hood Bi Musicalityrubia_siqueira_3No ratings yet

- Opera Movement DissertationDocument65 pagesOpera Movement DissertationWilliam ByramNo ratings yet

- FinalcourseproposalDocument9 pagesFinalcourseproposalapi-331290571No ratings yet

- Lavengood (2019) - Bespoke Music Theory, A Modular Core CurriculumDocument11 pagesLavengood (2019) - Bespoke Music Theory, A Modular Core CurriculumMiguel CampinhoNo ratings yet

- John Covach Jane Piper Clendinning and CDocument5 pagesJohn Covach Jane Piper Clendinning and CAriel Jara0% (1)

- University of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyDocument6 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyJosé A. CarrasquilloNo ratings yet

- A Complete History of Music for Schools, Clubs, and Private ReadingFrom EverandA Complete History of Music for Schools, Clubs, and Private ReadingNo ratings yet

- The Chronological Degradation of Piano Method Since The Early 19th CenturyDocument11 pagesThe Chronological Degradation of Piano Method Since The Early 19th CenturyNatalia PericNo ratings yet

- Non-Western Percussion in The Applied Studio: FocusDocument6 pagesNon-Western Percussion in The Applied Studio: FocusZikun ZhaoNo ratings yet

- Module 3 MapehDocument9 pagesModule 3 MapehmauriceNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive MusicianshipDocument7 pagesComprehensive MusicianshipTrena Anderson100% (1)

- IndonesianmusicdomainprojectpdfDocument51 pagesIndonesianmusicdomainprojectpdfapi-320645697No ratings yet

- University of Illinois Press, Council For Research in Music Education Bulletin of The Council For Research in Music EducationDocument12 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press, Council For Research in Music Education Bulletin of The Council For Research in Music Educationchua0726No ratings yet

- IES (By Page) (Forgacs) (Treatise) Gallus Dressler's Praecepta Musicae Poeticae (2009 05 24)Document7 pagesIES (By Page) (Forgacs) (Treatise) Gallus Dressler's Praecepta Musicae Poeticae (2009 05 24)HelenWongNo ratings yet

- Music in Classes O'zbek Classic Music Works of Study To Himself Specific PropertiesDocument3 pagesMusic in Classes O'zbek Classic Music Works of Study To Himself Specific PropertiesAcademic JournalNo ratings yet

- Primacy of The EarDocument5 pagesPrimacy of The EarMata Bana NajouNo ratings yet

- Personal Plan..es - enDocument4 pagesPersonal Plan..es - enClaudia Veloso AlvarezNo ratings yet

- HIP Librarians An Introduction To Historically Informed Performance For Music LibrariansDocument18 pagesHIP Librarians An Introduction To Historically Informed Performance For Music LibrariansRaíssa EncinasNo ratings yet

- Unit Topic and RationaleDocument4 pagesUnit Topic and Rationaleapi-237496570No ratings yet

- Miller Richard - Vocal PedagogyDocument18 pagesMiller Richard - Vocal PedagogyEdvan EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Parncutt Researchers Help ArtistsDocument25 pagesParncutt Researchers Help ArtistsMesmerNo ratings yet

- Candice Zhiuyan Luo Vocal Pedagogy Research Paper To Fach or Not To Fach ? - A Discussion On Appropriate Teachings of Fach in Trainings For Female Operatic High Voice March 21st 2020Document21 pagesCandice Zhiuyan Luo Vocal Pedagogy Research Paper To Fach or Not To Fach ? - A Discussion On Appropriate Teachings of Fach in Trainings For Female Operatic High Voice March 21st 2020CandiceNo ratings yet

- Musical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical TimesDocument5 pagesMusical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical TimesJoão Pedro ReigadoNo ratings yet

- 670 Portfolio Essay 1-2Document6 pages670 Portfolio Essay 1-2api-341096944No ratings yet

- Curricula and Conservatories: CommunitiesDocument30 pagesCurricula and Conservatories: CommunitiesAbram John Cabrales AlontagaNo ratings yet

- Midterm - Course ProposalsDocument5 pagesMidterm - Course Proposalsapi-329125614No ratings yet

- Vaccaj-Maki TranslationsDocument21 pagesVaccaj-Maki TranslationsScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- 08 Piano InstructionDocument10 pages08 Piano InstructionHugo FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Guide To Britten's Guide To The OrchestraDocument35 pagesCurriculum Guide To Britten's Guide To The Orchestradmviolin0% (1)

- Opportunities For Interdisciplinary Integration in Music EducationDocument4 pagesOpportunities For Interdisciplinary Integration in Music EducationAcademic JournalNo ratings yet

- Exploring Vocal Challenges Strategies For Song MasteryDocument6 pagesExploring Vocal Challenges Strategies For Song MasteryGrczhl GornesNo ratings yet

- Entry 4 Music Content KnowledgeDocument2 pagesEntry 4 Music Content Knowledgeapi-721561960No ratings yet

- Edward Dickinson - Education of A Music LoverDocument318 pagesEdward Dickinson - Education of A Music LoverGiacomo Detto Anche PiazzaNo ratings yet

- Music - OBEDocument16 pagesMusic - OBEaminul islamtalukderNo ratings yet

- Learning Music in GhanaDocument11 pagesLearning Music in GhanaJB TaylorNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Learning Classical Singing between European and Chinese SingersFrom EverandComparison of Learning Classical Singing between European and Chinese SingersNo ratings yet

- Bemusi 203 Course Coverage 1st Sem.2023Document102 pagesBemusi 203 Course Coverage 1st Sem.2023Keysee EgcaNo ratings yet

- The Child Voice in SingingDocument53 pagesThe Child Voice in SingingPIANO FACTOR by DanielNo ratings yet

- ELLIOTT, D. When I Sing - The Nature and Value of Choral Music EducationDocument8 pagesELLIOTT, D. When I Sing - The Nature and Value of Choral Music EducationdaisyfragosoNo ratings yet

- Below A Button With Correction NotesDocument8 pagesBelow A Button With Correction NotesScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Bel Canto in Its Golden Age - A Study of Its Teaching ConceptsFrom EverandBel Canto in Its Golden Age - A Study of Its Teaching ConceptsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Professional in Oral Tradition in Music Literature Lessons Methods of Familiarity With Samples of MusicDocument5 pagesProfessional in Oral Tradition in Music Literature Lessons Methods of Familiarity With Samples of MusicResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- ProfileDocument2 pagesProfileapi-374144689No ratings yet

- Music Policy BISBDocument4 pagesMusic Policy BISBJonathan SpinksNo ratings yet

- Master Music Education KodalyDocument15 pagesMaster Music Education Kodalystraf238100% (1)

- How To Understanding MusicDocument316 pagesHow To Understanding MusicKee Felix100% (1)

- Standard 4Document2 pagesStandard 4api-384048335No ratings yet

- Perception of Students and Teachers On Classical MusicDocument78 pagesPerception of Students and Teachers On Classical MusicJohn Carlo Pasigay0% (1)

- How Children Learn 76Document76 pagesHow Children Learn 76ubirajara.pires1100100% (1)

- Musical Interpretation - Its Laws and Principles and Their Application in Teaching and PerformingFrom EverandMusical Interpretation - Its Laws and Principles and Their Application in Teaching and PerformingNo ratings yet

- Preparation of Future Music Teachers For Their Professional Activities Througii Uzbek Classical MusicDocument6 pagesPreparation of Future Music Teachers For Their Professional Activities Througii Uzbek Classical MusicAcademic JournalNo ratings yet

- 23.full With Cover Page v2Document13 pages23.full With Cover Page v2MarijaNo ratings yet

- Artículo PercusiónDocument8 pagesArtículo PercusiónAnonymous yPy8PE1iNo ratings yet

- MusicDocument5 pagesMusicAireen BriosoNo ratings yet

- Justin Bland Interview ScriptDocument3 pagesJustin Bland Interview ScriptWolodymyr SmishkewychNo ratings yet

- LYRIC INTERVAL The Violin-1-V1Document4 pagesLYRIC INTERVAL The Violin-1-V1Wolodymyr SmishkewychNo ratings yet

- Sumer Is Icumen inDocument57 pagesSumer Is Icumen inWolodymyr SmishkewychNo ratings yet

- Revised Course Structure Template 1Document4 pagesRevised Course Structure Template 1Wolodymyr SmishkewychNo ratings yet

- Academic Calendar 2013-17Document77 pagesAcademic Calendar 2013-17Kris SwaminathanNo ratings yet

- Qatar - Joining InstructionsDocument2 pagesQatar - Joining InstructionsDeepu RavikumarNo ratings yet

- 439006Document6 pages439006sdfr100% (1)

- Asl 2 PresentationDocument9 pagesAsl 2 PresentationKenny BeeNo ratings yet

- CEVAS Philippines Occupational English Test Reading SubtestDocument4 pagesCEVAS Philippines Occupational English Test Reading SubtestORNPilipinasNo ratings yet

- 5054 PHYSICS: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersDocument6 pages5054 PHYSICS: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of Teachersmstudy123456No ratings yet

- Winter Carnival French Unit 2Document9 pagesWinter Carnival French Unit 2api-215073003No ratings yet

- 2013 Grade 2 English Mathematics ExemplarDocument23 pages2013 Grade 2 English Mathematics Exemplarnimanima50No ratings yet

- Seven School Curriculum Types and Their Classroom Implications - SimplyEducate - MeDocument29 pagesSeven School Curriculum Types and Their Classroom Implications - SimplyEducate - Mejxbm666No ratings yet

- MA Program Description 2018Document16 pagesMA Program Description 2018Aaishay HaqueNo ratings yet

- Act Prep Lesson 9Document7 pagesAct Prep Lesson 9api-439274163No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Plot Setting Character NarativeDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Plot Setting Character Narativeapi-425676975No ratings yet

- Mindanao Community School Banga, South CotabatoDocument3 pagesMindanao Community School Banga, South Cotabatoavinmanzano0% (1)

- Curiculum VitaeDocument10 pagesCuriculum VitaeSiti Adibah OthmanNo ratings yet

- New Inside Out Upper Intermediate Practice OnlineDocument15 pagesNew Inside Out Upper Intermediate Practice OnlineVictor Andres Pretell Rodriguez0% (1)

- Codes in Structural Engineering: Developments and Needs For International PracticeDocument10 pagesCodes in Structural Engineering: Developments and Needs For International PracticeSitaram JhaNo ratings yet

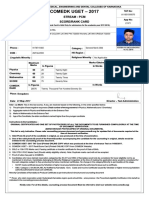

- Comedk Uget - 2017: Stream: PCM Score/Rank CardDocument1 pageComedk Uget - 2017: Stream: PCM Score/Rank Cardengg.satyaNo ratings yet

- Els 134 - Unit 2 - RealDocument19 pagesEls 134 - Unit 2 - Realtaw realNo ratings yet

- The Me PowerpointDocument16 pagesThe Me Powerpointapi-328192273No ratings yet

- EN Esbit: ExperienceDocument2 pagesEN Esbit: Experienceben_nesbitNo ratings yet

- National Yang Ming University: I. Course DescriptionDocument2 pagesNational Yang Ming University: I. Course DescriptionMa2FahriNo ratings yet

- Monitor System Unit MouseDocument2 pagesMonitor System Unit MouseMile GomillaNo ratings yet

- Exam Advice Law4132 2016Document2 pagesExam Advice Law4132 2016JazzmondNo ratings yet