Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 viewsCavafy Alexandria V 8888

Cavafy Alexandria V 8888

Uploaded by

Abou Mohamed Abdaoui1. Constantine Cavafy was a Greek poet born in 1863 in Alexandria, Egypt to a formerly prosperous Greek family. He spent his life and career in Alexandria.

2. Cavafy preferred Alexandria to Athens as a home because Alexandria represented the great period of Hellenism following Alexander the Great and was a cosmopolitan center of Greek culture, even as the population became more diverse over time.

3. In his poems, Cavafy explored themes of cultural blending, the threats to Greek identity and Hellenism over centuries, and the experiences of Greeks in the Diaspora as different cities and populations changed over time.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Egyptian Art (Phaidon Art Ebook)Document452 pagesEgyptian Art (Phaidon Art Ebook)G Davon Stubbs100% (13)

- Highly Irregular Arika OkrentDocument240 pagesHighly Irregular Arika OkrentWirelessNo ratings yet

- Apologetic History of The IndiesDocument8 pagesApologetic History of The IndiespomadadearnicaNo ratings yet

- History of Nubia and Abyssinia PDFDocument344 pagesHistory of Nubia and Abyssinia PDFkiros80% (5)

- Imaginary Life - QuotesDocument7 pagesImaginary Life - QuotesjamesNo ratings yet

- Romans, Barbarians, and The Transformation of The Roman World Cultural Interaction and The Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity PDFDocument400 pagesRomans, Barbarians, and The Transformation of The Roman World Cultural Interaction and The Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity PDFVitor Henrique Sanches100% (2)

- Dracula PPDocument47 pagesDracula PPapi-272853754100% (1)

- Alexander and The Amazon Queen - Márta MundingDocument18 pagesAlexander and The Amazon Queen - Márta MundingSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Kathryn Hinds-Ancient Celts (Barbarians!) (2009)Document81 pagesKathryn Hinds-Ancient Celts (Barbarians!) (2009)Gabriela Roman100% (3)

- Poetry: Selected and Introduced by Joseph BrodskyDocument8 pagesPoetry: Selected and Introduced by Joseph BrodskySokol Cunga100% (1)

- Greek LiteratureDocument20 pagesGreek LiteratureMichiko Kyung-soonNo ratings yet

- 21ST Week5 Journal Entry (Greek and Spanish Lit) Ready To PrintDocument2 pages21ST Week5 Journal Entry (Greek and Spanish Lit) Ready To PrintAngel Mahilum PanonNo ratings yet

- Bion - Theocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English ProseDocument126 pagesBion - Theocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English ProseLuciaNo ratings yet

- Voices From Cosmopolitan Alexandria PDFDocument236 pagesVoices From Cosmopolitan Alexandria PDFIn Magazine100% (1)

- Ancient Celts (Barbarians!) PDFDocument81 pagesAncient Celts (Barbarians!) PDFAnbr Cama100% (1)

- Persia in The History of CivilizationDocument4 pagesPersia in The History of CivilizationАбду ШахинNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare and the Coconuts: On post-apartheid South African cultureFrom EverandShakespeare and the Coconuts: On post-apartheid South African cultureNo ratings yet

- Leo Frobenius and AfricaDocument3 pagesLeo Frobenius and AfricaanansenseNo ratings yet

- Anthology of Georgian PoetryDocument233 pagesAnthology of Georgian PoetryPragyabgNo ratings yet

- Module 10 THE MIDDLE EAST ASIAN LITERATUREDocument18 pagesModule 10 THE MIDDLE EAST ASIAN LITERATURECarie Joy UrgellesNo ratings yet

- Theocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English Prose by Bion, of Phlossa Near SmyrnaDocument99 pagesTheocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English Prose by Bion, of Phlossa Near SmyrnaGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Modern Scottish Minstrel 3Document332 pagesModern Scottish Minstrel 3Fe0% (1)

- The Captive and the Gift: Cultural Histories of Sovereignty in Russia and the CaucasusFrom EverandThe Captive and the Gift: Cultural Histories of Sovereignty in Russia and the CaucasusRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Art and ArchitectureDocument37 pagesArt and ArchitectureChris HaerringerNo ratings yet

- 10-1 021Document11 pages10-1 021WasanH.IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Alexandria Amidst Fragrant History and Saffron SoilFrom EverandAlexandria Amidst Fragrant History and Saffron SoilNo ratings yet

- Knowledge is Light: Travellers in the Near EastFrom EverandKnowledge is Light: Travellers in the Near EastKatherine SalahiNo ratings yet

- GREEK EPICS Exer. 2 8Document4 pagesGREEK EPICS Exer. 2 8Mr. ZeusNo ratings yet

- Arab CivilizationDocument8 pagesArab CivilizationHaris HadžibaščauševićNo ratings yet

- The Classical TraditionDocument8 pagesThe Classical TraditionDavo Lo SchiavoNo ratings yet

- QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesQuestionnaireDiana Ninel Rodriguez LopezNo ratings yet

- Joseph Julius Jackson - History of The Black Man (1921)Document48 pagesJoseph Julius Jackson - History of The Black Man (1921)chyoungNo ratings yet

- Greece Historical Background 2Document19 pagesGreece Historical Background 2Ayeza MillaresNo ratings yet

- Huns (Barbarians!)Document82 pagesHuns (Barbarians!)王骏恺100% (3)

- Karram Mohab Alexandria 2018Document6 pagesKarram Mohab Alexandria 2018jonathan.johncarolNo ratings yet

- Tekstovi Za PrevodDocument10 pagesTekstovi Za PrevodDusan SpasojevicNo ratings yet

- The Phoenician Sonnets: Mediterranean mysteries along ancient trading routesFrom EverandThe Phoenician Sonnets: Mediterranean mysteries along ancient trading routesNo ratings yet

- The Grand Tour "The Picturesque" and "The Sublime"Document5 pagesThe Grand Tour "The Picturesque" and "The Sublime"Cosmina VilceanuNo ratings yet

- Greece: Painted by John Fulleylove; described by J.A. McClymontFrom EverandGreece: Painted by John Fulleylove; described by J.A. McClymontNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Leucippe and Clitophon - Delphi Complete Works of Achilles Tatius (Illustrated)From EverandThe Adventures of Leucippe and Clitophon - Delphi Complete Works of Achilles Tatius (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Islam and The OccidentDocument33 pagesIslam and The OccidentAn LehnsherrNo ratings yet

- Bsee 35 ReviewerDocument15 pagesBsee 35 Reviewer肖泛No ratings yet

- Stories From the Center of the World: New Middle East FictionFrom EverandStories From the Center of the World: New Middle East FictionJordan ElgrablyNo ratings yet

- Rain Song Article With HighlightsDocument6 pagesRain Song Article With HighlightsShivam ParekhNo ratings yet

- The Spectator Alexander in Afghanistan Project - Matthew LeemingDocument9 pagesThe Spectator Alexander in Afghanistan Project - Matthew LeemingMarsyas PeriandrouNo ratings yet

- Ancient Semitic CivilizationsDocument278 pagesAncient Semitic Civilizationse_s_grigorova100% (2)

- The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other StoriesFrom EverandThe Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (240)

- Letter To King George IIIDocument4 pagesLetter To King George IIIKeon Woo OhNo ratings yet

- 3.conklin (Eng.) - A Mission To Civilize PDFDocument24 pages3.conklin (Eng.) - A Mission To Civilize PDFMary100% (1)

- Inventing The BarbarianDocument295 pagesInventing The BarbarianHenry Hall100% (1)

- Pocock-Barbarism and ReligionDocument355 pagesPocock-Barbarism and Religionulianov333100% (1)

- Ancient Rome in Modern Europe and United StatesDocument17 pagesAncient Rome in Modern Europe and United StatesJordi Teixidor AbelendaNo ratings yet

- Nomad DBQ AP World HistoryDocument3 pagesNomad DBQ AP World HistoryRonald Muldeo PritipaulNo ratings yet

- Terry Jones' Barbarians - Terry JonesDocument463 pagesTerry Jones' Barbarians - Terry JonesOsnat Neulander100% (1)

- The Problem Called LanguageDocument23 pagesThe Problem Called LanguagemampiyNo ratings yet

- Valladolid DebateDocument2 pagesValladolid Debateapi-368121935No ratings yet

- De Las Casas vs. Sepulveda On Native AmericansDocument6 pagesDe Las Casas vs. Sepulveda On Native AmericansRishi LullaNo ratings yet

- Sepulveda v. de Las CasasDocument2 pagesSepulveda v. de Las CasasNova GaveNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Discovery of Chinese Fiction The Water Margin and The Making of A National Canon (William C. Hedberg) (Z-Library)Document265 pagesThe Japanese Discovery of Chinese Fiction The Water Margin and The Making of A National Canon (William C. Hedberg) (Z-Library)PauloCésarNo ratings yet

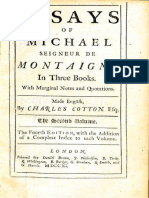

- Montaigne-Of CannibalsDocument19 pagesMontaigne-Of CannibalsKasra SeifiNo ratings yet

- Some Aspects of Aristotle's Theory of SlaveryDocument4 pagesSome Aspects of Aristotle's Theory of Slaveryilovemondays1No ratings yet

- Huns-Barbarians Compress - PDF 5Document81 pagesHuns-Barbarians Compress - PDF 5Burak Cengo tvNo ratings yet

- ISAIAH PARKER The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas TEXTDocument5 pagesISAIAH PARKER The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas TEXTparkerisNo ratings yet

- Guided Notes-Life After The Western Roman EmpireDocument10 pagesGuided Notes-Life After The Western Roman Empireapi-526325840No ratings yet

- 5 History of Foreign MusicDocument364 pages5 History of Foreign MusicglassyglassNo ratings yet

- Lavan, Myles - Slaves To Rome. Paradigms of Empire in Roman Culture (Cambridge Classical Studies, 2013, 304pp) - LZDocument304 pagesLavan, Myles - Slaves To Rome. Paradigms of Empire in Roman Culture (Cambridge Classical Studies, 2013, 304pp) - LZMiloš Nenezić100% (3)

- 1893 Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893 by Leitner SDocument288 pages1893 Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893 by Leitner SBilal Afridi100% (1)

- Atlantean Kodex Interview (WAR ON ALL FRONTS Fanzine)Document4 pagesAtlantean Kodex Interview (WAR ON ALL FRONTS Fanzine)Matthew MooreNo ratings yet

- Mohammed Charlemagne Revisited The History of A Controversy First Edition Emmet Scott Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesMohammed Charlemagne Revisited The History of A Controversy First Edition Emmet Scott Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFkristina.mowery491100% (10)

- Study of History 5018264 MBPDocument638 pagesStudy of History 5018264 MBPAlperenler44100% (2)

- Nietzsche On RhetoricDocument39 pagesNietzsche On RhetoricvpglamNo ratings yet

Cavafy Alexandria V 8888

Cavafy Alexandria V 8888

Uploaded by

Abou Mohamed Abdaoui0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views2 pages1. Constantine Cavafy was a Greek poet born in 1863 in Alexandria, Egypt to a formerly prosperous Greek family. He spent his life and career in Alexandria.

2. Cavafy preferred Alexandria to Athens as a home because Alexandria represented the great period of Hellenism following Alexander the Great and was a cosmopolitan center of Greek culture, even as the population became more diverse over time.

3. In his poems, Cavafy explored themes of cultural blending, the threats to Greek identity and Hellenism over centuries, and the experiences of Greeks in the Diaspora as different cities and populations changed over time.

Original Description:

Original Title

Cavafy Alexandria v 8888

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1. Constantine Cavafy was a Greek poet born in 1863 in Alexandria, Egypt to a formerly prosperous Greek family. He spent his life and career in Alexandria.

2. Cavafy preferred Alexandria to Athens as a home because Alexandria represented the great period of Hellenism following Alexander the Great and was a cosmopolitan center of Greek culture, even as the population became more diverse over time.

3. In his poems, Cavafy explored themes of cultural blending, the threats to Greek identity and Hellenism over centuries, and the experiences of Greeks in the Diaspora as different cities and populations changed over time.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

52 views2 pagesCavafy Alexandria V 8888

Cavafy Alexandria V 8888

Uploaded by

Abou Mohamed Abdaoui1. Constantine Cavafy was a Greek poet born in 1863 in Alexandria, Egypt to a formerly prosperous Greek family. He spent his life and career in Alexandria.

2. Cavafy preferred Alexandria to Athens as a home because Alexandria represented the great period of Hellenism following Alexander the Great and was a cosmopolitan center of Greek culture, even as the population became more diverse over time.

3. In his poems, Cavafy explored themes of cultural blending, the threats to Greek identity and Hellenism over centuries, and the experiences of Greeks in the Diaspora as different cities and populations changed over time.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 2

1

Nobel Laureate Seferis wrote that Cavafy is

a difficult poet because you need to know

history to understand him.

We have come to appreciate Cavafy because

we know that, by writing about the ancient

world, he is really writing about us.

Cavafys Alexandria

Gregory Jusdanis,

Professor of Greek Studies,

Jusdanis.1@OSU.edu

Constantine Cavafy [K. H. KABAuHE]

is considered 1 of the greatest Greek

poets. Most knowledgeable people list

Cavafy as one of the finest European

poets of the 20

th

century. He has been

translated in countless languages, with

many editions in English. A new

translation of his appears every few

years. This is unprecedented for a

Greek poet.

The last of 9

children, Cavafy was

born in 1863 in

Alexandria, Egypt

to a prosperous

Greek family. His

mother, Haricleia

descended from one

of the aristocratic families of

Constantinople who had settled there in

1680 from Chios. His father, Peter John

became one of Alexandrias leading

merchants acquiring an enormous fortune.

After his fathers death, however, when

the poet was only 7 years old, the family

fortune was lost through mismanagement.

Cavafy, the child of grand bourgeois,

grew up in poverty, aware, however, of

being socially fallen. At the age of 29, he

took a position as a clerk in the

Department of Irrigation. He died of

throat cancer on 29 April 1933, on his 70

th

birthday.

In Cavafys lifetime, Alexandria was one

of the 4 most important centers of

Hellenism, along with, Constantinople,

Athens, and Smyrna. Greeks, along with

other foreigners, had been encouraged to

settle there in the 19

th

century by the

Ottoman viceroy Mohammed Aly who

wanted to modernize Egypt. Alexandria

attracted sizable communities of

foreigners. By 1917, the 30,000Greeks

was most visible ethnic group, in a city of

435,000. The Greeks came to Alexandria

largely from the Hellenic diaspora, and

dispersed from there throughout the Near

East and the Balkans.

When Cavafy strolled through the streets

of Alexandria, he felt that he was walking

through a Greek city. There were Greek

churches, schools, book stores, cafes,

restaurants, newspapers, magazines, and

voluntary organizations. It was a wealthy

and educated community that supported

culture both in Egypt as well as Greece.

Some of the great cultural benefactors of

Greece came from Egypt. Alexandria

became synonymous with culture, arts,

cosmopolitanism, and commerce.

This is why Cavafy never wanted to

move to Greece. He felt perfectly at home

in this center of Hellenism, seeing himself

as a member of the diaspora rather than of

mainland Greece. When in his old age he

was invited by a friend to move to

Athens, Cavafy refused. Mohammed Aly

Square is my aunt, he responded; Rue

Cherif Pacha is my first cousin and the

Rue de Ramleh is my second. How could I

leave them? It is these that he turned into

art, as the poet of In the Same Place

who looks out onto his neighborhood:

I created you in joy and sorrow./ And

you have turned into sentiment for me.

Another reason Cavafy preferred

Alexandria to Athens is that the Egyptian

city represented for him the great period

of Hellenism that was inaugurated by

Alexander the Great. It was he who

founded Alexandria in 331 BC, a city that

became one of the most splendid in the

ancient world and the nucleus of Roman

Egypt. The lighthouse on the Pharos islet

in the harbor stood for many as a beacon

of culture and the Library, the grandest

of the ancient world, was a symbol of the

city as a hub of learning and education.

Ancient Alexandria was a mix of races,

religions, and nationalities. So too was

Cavafys Alexandria.

Cavafy was acutely interested in this

type of cultural fusion that was

characteristic of Alexanders Hellenistic

Empire. Alexander the Great encouraged

Greek immigration to the East and

fostered interethnic marriages. Many of

Cavafys poems deal with this theme of

cultural and racial fusion. The speaker

In a Town of Osroini boasts: We are

a mix here: Syrians, Greeks, Armenians,

Medes.

The poem In the Year 200 BC calls this

assortment the great new Greek world:

We the Alexandrians, the Antiochians,

the Selefkians, and the countless

other Greeks of Egypt and Syria,

and those in Media, and Persia, and all the rest:

with our far-flung supremacy,

our flexible policy of judicious integration,

and our Common Greek Language

which we carried as far as Bactria, as far as the Indians.

Cavafy also understood that Hellenism was

threatened after so many centuries of ethnic,

racial, and cultural blending. In the poem,

Poseidonians, he explores the fate of the

inhabitants of a Greek colony in south central

Italy, who had forgotten their Greek tongue

and culture after centuries of mingling with

Tyrrhnians, Latins, and other foreigners [see

also poem on next page]. The only connection to

their ancestors was a Greek Festival they

celebrated with beautiful rites, lyres, flutes,

contests, and crowns. At the festivals end,

they always talked about their old customs and

repeated their Greek names, which only a few

of them understood now.

because they remembered that they too were Greeks

they too citizens of Magna Graecia once upon a time;

but how theyd fallen, what theyd now become,

living and speaking like barbarians,

excluded--what a catastrophe!

from the Hellenic way of life.

One of the reasons for Cavafys extraordinary

popularity in Greece, the United States, and the

entire world is that he understood the conditions

of life in the late 20

th

and early 21

st

century.

He knew 100 years earlier that by turning to the

history of his native city, he would find

parallels to our own modern society: imperial

systems, globalization, transnationalism,

multiculturalism.

Cavafys genius lay in showing how

Hellenism flourished in this ancient world and

how ordinary people tried to hold on to this way

of life and to this form of identity in the ensuing

centuries.

National Geographics

Millennia World Cultural Capitals

0000 - Alexandria of Hellenic Egypt

1000 - Cordoba of Islamic Spain!

2000 - New York of multiethnic USA!

2

Waiting for the Barbarians

Cavafy, Constantine P. (1904)

What are we waiting for, assembled in the forum?

The barbarians are to arrive today.

Why such inaction in the Senate?

Why do the Senators sit and pass no laws?

Because the barbarians are to arrive today.

What laws can the Senators pass any more?

When the barbarians come they will make the laws.

Why did our emperor wake up so early,

and sits at the greatest gate of the city,

on the throne, solemn, wearing the crown?

Because the barbarians are to arrive today.

And the emperor waits to receive their chief.

Indeed he has prepared to give him a scroll.

Therein he inscribed many titles and names of honor.

Why have our two consuls and the praetors come out

today in their red, embroidered togas;

why do they wear amethyst-studded bracelets,

and rings with brilliant, glittering emeralds;

why are they carrying costly canes today,

wonderfully carved with silver and gold?

Because the barbarians are to arrive today,

and such things dazzle the barbarians.

Why don't the worthy orators come as always

to make their speeches, to have their say?

Because the barbarians are to arrive today;

and they get bored with eloquence and orations.

Why all of a sudden this unrest and confusion? (How

solemn the faces have become).

Why are the streets and squares clearing quickly,

and all return to their homes, so deep in thought?

Because night is here but the barbarians have not come.

And some people arrived from the borders,

and said that there are no longer any barbarians.

And now what shall become of us without any barbarians?

Those people were some kind of solution.

KABAuHE, K. H.

You might also like

- Egyptian Art (Phaidon Art Ebook)Document452 pagesEgyptian Art (Phaidon Art Ebook)G Davon Stubbs100% (13)

- Highly Irregular Arika OkrentDocument240 pagesHighly Irregular Arika OkrentWirelessNo ratings yet

- Apologetic History of The IndiesDocument8 pagesApologetic History of The IndiespomadadearnicaNo ratings yet

- History of Nubia and Abyssinia PDFDocument344 pagesHistory of Nubia and Abyssinia PDFkiros80% (5)

- Imaginary Life - QuotesDocument7 pagesImaginary Life - QuotesjamesNo ratings yet

- Romans, Barbarians, and The Transformation of The Roman World Cultural Interaction and The Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity PDFDocument400 pagesRomans, Barbarians, and The Transformation of The Roman World Cultural Interaction and The Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity PDFVitor Henrique Sanches100% (2)

- Dracula PPDocument47 pagesDracula PPapi-272853754100% (1)

- Alexander and The Amazon Queen - Márta MundingDocument18 pagesAlexander and The Amazon Queen - Márta MundingSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Kathryn Hinds-Ancient Celts (Barbarians!) (2009)Document81 pagesKathryn Hinds-Ancient Celts (Barbarians!) (2009)Gabriela Roman100% (3)

- Poetry: Selected and Introduced by Joseph BrodskyDocument8 pagesPoetry: Selected and Introduced by Joseph BrodskySokol Cunga100% (1)

- Greek LiteratureDocument20 pagesGreek LiteratureMichiko Kyung-soonNo ratings yet

- 21ST Week5 Journal Entry (Greek and Spanish Lit) Ready To PrintDocument2 pages21ST Week5 Journal Entry (Greek and Spanish Lit) Ready To PrintAngel Mahilum PanonNo ratings yet

- Bion - Theocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English ProseDocument126 pagesBion - Theocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English ProseLuciaNo ratings yet

- Voices From Cosmopolitan Alexandria PDFDocument236 pagesVoices From Cosmopolitan Alexandria PDFIn Magazine100% (1)

- Ancient Celts (Barbarians!) PDFDocument81 pagesAncient Celts (Barbarians!) PDFAnbr Cama100% (1)

- Persia in The History of CivilizationDocument4 pagesPersia in The History of CivilizationАбду ШахинNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare and the Coconuts: On post-apartheid South African cultureFrom EverandShakespeare and the Coconuts: On post-apartheid South African cultureNo ratings yet

- Leo Frobenius and AfricaDocument3 pagesLeo Frobenius and AfricaanansenseNo ratings yet

- Anthology of Georgian PoetryDocument233 pagesAnthology of Georgian PoetryPragyabgNo ratings yet

- Module 10 THE MIDDLE EAST ASIAN LITERATUREDocument18 pagesModule 10 THE MIDDLE EAST ASIAN LITERATURECarie Joy UrgellesNo ratings yet

- Theocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English Prose by Bion, of Phlossa Near SmyrnaDocument99 pagesTheocritus Bion and Moschus Rendered Into English Prose by Bion, of Phlossa Near SmyrnaGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Modern Scottish Minstrel 3Document332 pagesModern Scottish Minstrel 3Fe0% (1)

- The Captive and the Gift: Cultural Histories of Sovereignty in Russia and the CaucasusFrom EverandThe Captive and the Gift: Cultural Histories of Sovereignty in Russia and the CaucasusRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Art and ArchitectureDocument37 pagesArt and ArchitectureChris HaerringerNo ratings yet

- 10-1 021Document11 pages10-1 021WasanH.IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Alexandria Amidst Fragrant History and Saffron SoilFrom EverandAlexandria Amidst Fragrant History and Saffron SoilNo ratings yet

- Knowledge is Light: Travellers in the Near EastFrom EverandKnowledge is Light: Travellers in the Near EastKatherine SalahiNo ratings yet

- GREEK EPICS Exer. 2 8Document4 pagesGREEK EPICS Exer. 2 8Mr. ZeusNo ratings yet

- Arab CivilizationDocument8 pagesArab CivilizationHaris HadžibaščauševićNo ratings yet

- The Classical TraditionDocument8 pagesThe Classical TraditionDavo Lo SchiavoNo ratings yet

- QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesQuestionnaireDiana Ninel Rodriguez LopezNo ratings yet

- Joseph Julius Jackson - History of The Black Man (1921)Document48 pagesJoseph Julius Jackson - History of The Black Man (1921)chyoungNo ratings yet

- Greece Historical Background 2Document19 pagesGreece Historical Background 2Ayeza MillaresNo ratings yet

- Huns (Barbarians!)Document82 pagesHuns (Barbarians!)王骏恺100% (3)

- Karram Mohab Alexandria 2018Document6 pagesKarram Mohab Alexandria 2018jonathan.johncarolNo ratings yet

- Tekstovi Za PrevodDocument10 pagesTekstovi Za PrevodDusan SpasojevicNo ratings yet

- The Phoenician Sonnets: Mediterranean mysteries along ancient trading routesFrom EverandThe Phoenician Sonnets: Mediterranean mysteries along ancient trading routesNo ratings yet

- The Grand Tour "The Picturesque" and "The Sublime"Document5 pagesThe Grand Tour "The Picturesque" and "The Sublime"Cosmina VilceanuNo ratings yet

- Greece: Painted by John Fulleylove; described by J.A. McClymontFrom EverandGreece: Painted by John Fulleylove; described by J.A. McClymontNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Leucippe and Clitophon - Delphi Complete Works of Achilles Tatius (Illustrated)From EverandThe Adventures of Leucippe and Clitophon - Delphi Complete Works of Achilles Tatius (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Islam and The OccidentDocument33 pagesIslam and The OccidentAn LehnsherrNo ratings yet

- Bsee 35 ReviewerDocument15 pagesBsee 35 Reviewer肖泛No ratings yet

- Stories From the Center of the World: New Middle East FictionFrom EverandStories From the Center of the World: New Middle East FictionJordan ElgrablyNo ratings yet

- Rain Song Article With HighlightsDocument6 pagesRain Song Article With HighlightsShivam ParekhNo ratings yet

- The Spectator Alexander in Afghanistan Project - Matthew LeemingDocument9 pagesThe Spectator Alexander in Afghanistan Project - Matthew LeemingMarsyas PeriandrouNo ratings yet

- Ancient Semitic CivilizationsDocument278 pagesAncient Semitic Civilizationse_s_grigorova100% (2)

- The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other StoriesFrom EverandThe Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (240)

- Letter To King George IIIDocument4 pagesLetter To King George IIIKeon Woo OhNo ratings yet

- 3.conklin (Eng.) - A Mission To Civilize PDFDocument24 pages3.conklin (Eng.) - A Mission To Civilize PDFMary100% (1)

- Inventing The BarbarianDocument295 pagesInventing The BarbarianHenry Hall100% (1)

- Pocock-Barbarism and ReligionDocument355 pagesPocock-Barbarism and Religionulianov333100% (1)

- Ancient Rome in Modern Europe and United StatesDocument17 pagesAncient Rome in Modern Europe and United StatesJordi Teixidor AbelendaNo ratings yet

- Nomad DBQ AP World HistoryDocument3 pagesNomad DBQ AP World HistoryRonald Muldeo PritipaulNo ratings yet

- Terry Jones' Barbarians - Terry JonesDocument463 pagesTerry Jones' Barbarians - Terry JonesOsnat Neulander100% (1)

- The Problem Called LanguageDocument23 pagesThe Problem Called LanguagemampiyNo ratings yet

- Valladolid DebateDocument2 pagesValladolid Debateapi-368121935No ratings yet

- De Las Casas vs. Sepulveda On Native AmericansDocument6 pagesDe Las Casas vs. Sepulveda On Native AmericansRishi LullaNo ratings yet

- Sepulveda v. de Las CasasDocument2 pagesSepulveda v. de Las CasasNova GaveNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Discovery of Chinese Fiction The Water Margin and The Making of A National Canon (William C. Hedberg) (Z-Library)Document265 pagesThe Japanese Discovery of Chinese Fiction The Water Margin and The Making of A National Canon (William C. Hedberg) (Z-Library)PauloCésarNo ratings yet

- Montaigne-Of CannibalsDocument19 pagesMontaigne-Of CannibalsKasra SeifiNo ratings yet

- Some Aspects of Aristotle's Theory of SlaveryDocument4 pagesSome Aspects of Aristotle's Theory of Slaveryilovemondays1No ratings yet

- Huns-Barbarians Compress - PDF 5Document81 pagesHuns-Barbarians Compress - PDF 5Burak Cengo tvNo ratings yet

- ISAIAH PARKER The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas TEXTDocument5 pagesISAIAH PARKER The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas TEXTparkerisNo ratings yet

- Guided Notes-Life After The Western Roman EmpireDocument10 pagesGuided Notes-Life After The Western Roman Empireapi-526325840No ratings yet

- 5 History of Foreign MusicDocument364 pages5 History of Foreign MusicglassyglassNo ratings yet

- Lavan, Myles - Slaves To Rome. Paradigms of Empire in Roman Culture (Cambridge Classical Studies, 2013, 304pp) - LZDocument304 pagesLavan, Myles - Slaves To Rome. Paradigms of Empire in Roman Culture (Cambridge Classical Studies, 2013, 304pp) - LZMiloš Nenezić100% (3)

- 1893 Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893 by Leitner SDocument288 pages1893 Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893 by Leitner SBilal Afridi100% (1)

- Atlantean Kodex Interview (WAR ON ALL FRONTS Fanzine)Document4 pagesAtlantean Kodex Interview (WAR ON ALL FRONTS Fanzine)Matthew MooreNo ratings yet

- Mohammed Charlemagne Revisited The History of A Controversy First Edition Emmet Scott Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesMohammed Charlemagne Revisited The History of A Controversy First Edition Emmet Scott Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFkristina.mowery491100% (10)

- Study of History 5018264 MBPDocument638 pagesStudy of History 5018264 MBPAlperenler44100% (2)

- Nietzsche On RhetoricDocument39 pagesNietzsche On RhetoricvpglamNo ratings yet