Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reconsideration Order

Reconsideration Order

Uploaded by

DeadlyClearCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reconsideration Order

Reconsideration Order

Uploaded by

DeadlyClearCopyright:

Available Formats

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 1 of 33 2379

PageID #:

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF HAWAII

TIMOTHY J. FITZGERALD, individually, and GORDON P.A. SMITH, individually,

) ) ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) PACIFIC SOURCE, INC., a ) Washington corporation, and MARK ) MASON, individually and as ) President of Pacific Source, Inc. and ) DOES 1 through 20 inclusive, ) ) Defendants. ) )

CV. NO. 11-00111 DAE-KSC

ORDER: (1) GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART PLAINTIFFS MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION; AND (2) GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART DEFENDANTS MOTION TO DISMISS FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT, OR, IN THE ALTERNATIVE, FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT On July 24, 2012, the Court heard Plaintiffs Motion for Reconsideration. Arnold Thielens Phillips II, Esq., appeared at the hearing on behalf of Plaintiffs; Simon Klevansky, Esq., and Nicole D. Stucki, Esq., appeared at the hearing on behalf of Defendants. After reviewing the Motion and the supporting and opposing memoranda, the Court hereby GRANTS IN PART and

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 2 of 33 2380

PageID #:

DENIES IN PART Plaintiffs Motion for Reconsideration. (Doc. # 89.) FACTUAL BACKGROUND This case stems out of bonding agreements involving the construction of two separate properties on Maui. Defendant Pacific Source, Inc. (PSI) is a material supplier in the State of Washington that also provides materialmens construction bonds on projects pursuant to which it serves as a surety. (Doc. # 131 3.) For several years, PSI provided construction bonds for various APH projects and sold APH building materials for those projects. (Doc. # 13-1 47.) As surety, PSI would receive funds from the lenders of the projects and would pay the amounts owed to the subcontractors and other material suppliers. (Id. 8.) According to PSI, APH became delinquent on several construction projects to which PSI had supplied materials. (Id. 11.) Plaintiffs Timothy Fitzgerald (Fitzgerald) and Gordon Smith (Smith) (collectively, Plaintiffs) each entered into bonding agreements with PSI for the construction of their respective homes. (FAC, Doc. # 56 11; Docs. # 60-5; 60-6.) Plaintiffs allege that PSI misused the bonded funds for their projects by diverting some of the funds to pay invoices for unrelated projects. (FAC 2426; 37, 42, 56; 7778.) Plaintiffs assert that as a result of PSIs actions, they had to advance their own funds to complete the construction of their respective projects. (FAC 57, 79.) Fitzgerald further

2

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 3 of 33 2381

PageID #:

alleged that the advancement of his funds resulted in him filing for Chapter XIII bankruptcy protection. (FAC 58.) I. Fitzgeralds Vineyard Project On August 27, 2007, Fitzgerald and Virginia Parsons (Virginia Parsons or Parsons), who worked together at Aloha Package Homes (APH),1 entered into a construction contract (Vineyard Construction Contract) with contractor Thomas A. Martin (Martin) to build a residence at 2276 Vineyard Street, Wailuku, Hawaii (Vineyard Project). (Doc. # 69-2; Fitzgerald Aff., Doc. # 67-1 4.) The Vineyard Construction Contract provided that Martin would pay for all material, labor, equipment and other necessary items to complete the Vineyard Project, and that Parsons and Fitzgerald would in return pay Martin $393,599.00. (Doc. # 69-2.) One of the general conditions of the contract was that Martin furnish a performance and payment bond in an amount equal to one hundred percent (100%) of the contract price. (Id.) On or about December 17, 2007, Fitzgerald, Parsons, Martin and PSI entered into a Uniform Performance Bond, Assignment of Contract and Agreement Bond (Vineyard Bond). (Doc. # 69-3.) On December 17, 2007, Fitzgerald and

Parsons was president of Aloha Package Homes (APH). APH was a company that provided homebuilding services, including designing homes and providing materials.

3

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 4 of 33 2382

PageID #:

Parsons entered into a construction to mortgage contract with American Savings Bank (doc. # 69-4), and construction draws were funded to the PSI bonding account. (FAC 15; Doc. # 13-1 8.) On February 18, 2009, Fitzgerald, along with Parsons and her husband, Dale Parsons, signed a Limited Agreement of Guaranty and Indemnity, guaranteeing payment of all credit extended by PSI to APH. (Doc. # 69-28.) Plaintiffs allege that Defendants diverted Vineyard Project bonded funds to pay invoices for unrelated projects, and that during the construction Mark Mason (Mason), in his capacity as president of PSI, refused to pay a Request for Payment on the Vineyard Project. (FAC 22, 37, 51.) According to the FAC, this required Fitzgerald to pay for any shortfall in the bond account if he wanted his home finished. (FAC 37, 51.) Plaintiffs allege that when construction was complete, Fitzgerald should have received unused money from the bond fund and expected to be reimbursed for any advancement of his personal funds to complete the project. (Id. 54.) Plaintiffs also allege that PSI made Fitzgerald liable for falsified unpaid Vineyard Project invoices planted on an APH aging statement that were previously paid for. (Doc. # 68 at 1011.) Plaintiffs further allege that Defendants falsified certain financial records and communications regarding the project bond statements, checks and invoices. (FAC 82.)

4

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 5 of 33 2383

PageID #:

II.

Smith Project On December 4, 2009, Smith and his wife (who is not a party in this

action) contracted with APH to supply building materials and oversee the financial expenditures of the construction, including draws and payment disbursements. (Smith Aff., Doc. # 67-2 11; Doc. # 67-9.) On the same day, the Smiths entered into a construction contract (first Smith construction contract) with Lehua Management Services (Lehua) and APH. (Doc. # 67-8.) Under the construction contract, in which Lehua was named contractor, the Smiths agreed to pay APH, and APH agreed to distribute, the funds for the project. (Id.) The contract also referenced the APH materials contract. (Id.) The total figure for the Smith Project was $430,000. (Doc. # 67-8.) According to Smith, the figure included $282,693 for labor provided by Lehua, a $38,307 contingency fund for some of the materials that Smith previously purchased, $106,850 for the APH building materials package, and $2,150 for an administrative fee to PSI for bonding. (Smith Aff. 9, 13.) Lehua decided to use PSI for bonding the Smith Project. (Parsons Aff., Doc. # 67-3 22.) According to Plaintiffs, on January 19, 2010, Mason informed Parsons by phone that he would not bond the Smith Project unless she rewrote the construction contract and removed references to APH. (Parsons Aff.

5

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 6 of 33 2384

PageID #:

23.) On or about January 25, 2010, the Smiths entered into a new construction contract (Smith Construction Contract) with Lehua only; the contract eliminated references to APH, including any reference to an APH materials contract. (Doc. # 67-11; Parsons Decl. Ex. 29.) The Smith Construction Contract states in part that Owner hereby agrees to pay Contractor through Contractors bonding entity, and Contractors bonding entity agrees to distribute the funds for the project. (Doc. # 67-11.) Unlike the Vineyard Construction Contract, the Smith Construction Contract also contains a contingency/allowance provision that states: The total construction cost includes an owner contingency/allowance fund of $32,565.00 for building materials as specified per the materials contract that Owner has agreed to supply. (Doc. # 56-34; Doc. # 69-34.) A January 29, 2010 Change Order by APH, which was approved by Smith, deleted certain kitchen materials and thus added $5,742.00 to the contingency amount, bringing the total amount allocated to contingency/allowance to $38,306.77. (Doc. # 60-8.) The $38,306.77 is included in the $430,000.00 contract price. (Duvauchelle Decl, Doc. # 60-2 11; Smith Aff. 13.) On February 2, 2010, Smith, Lehua, and PSI signed a Uniform Performance Bond, Assignment of Contract and Agreement Bond (Smith Bond)

6

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 7 of 33 2385

PageID #:

for the construction of a residence at 3076 Alaneo Place, Wailuku, Hawaii 96793 (Smith Project). (Doc. # 60-6.) PSI was the surety on the bond, and as the surety, received money from the project lender and disbursed funds to subcontractors. (Mason Decl., Doc. # 60-1 3; Duvauchelle Decl. 8.) Through January and February, APH continued to provide its services to Lehua and the Smiths. (Parsons Aff. 28.) On February 16, 2010, Parsons sent PSI a budget for the Smith Project that included $27,869 for APH. (Parsons Aff. 29; Doc. # 67-12.) On February 18, 2010, Parsons submitted a Request for Payment for $27,869$25,774 of which was requested from the first construction draw. (Parsons Aff. 31.) On or about February 22, 2010, a construction draw from the bonded Smith construction loan in the amount of $180,600 was funded to PSIs bonding account. (Id. 63; Doc. # 69-36.) According to Plaintiffs, PSI informed Parsons that Mason would not release the funds Parsons requested. (Parsons Aff. 34.) According to Plaintiffs, Lehua began ordering materials

directly from PSI. (Id. 64.) On February 26, 2010, Mason sent Parsons an email stating: We are applying the funds due APH from the Smith job, $25,774.00, as an offset against your account to Pacific Source. (Doc. # 69-39.) PSI has stated that it received funds from the lender for Smiths project, a portion of which otherwise would be

7

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 8 of 33 2386

PageID #:

due to APH, but that it applied those funds as an offset against the outstanding debt APH owed PSI on a different construction project. (Doc. # 13-1 11.) Plaintiffs allege, inter alia, that on April 6, 2010, PSI used Smiths funds to pay Vineyard Project invoices that were improperly added to the APH aging statement. Plaintiffs further assert that as a result, Smith had to advance $33,437.55 of his own funds to complete the construction of his home. (FAC 79.) PROCEDURAL HISTORY On February 22, 2011, Fitzgerald, Smith, APH, and Virginia and Dale Parsons filed a Complaint against PSI and Mason. (Doc. # 1.) On April 18, 2011, Defendants filed a Motion to Dismiss the Complaint. (Doc. # 13.) On July 5, 2011, the Plaintiffs filed an opposition to the Motion to Dismiss. (Doc. # 32.) On November 21, 2011, Defendants filed a Reply, stating that they have entered into settlement agreements with bankruptcy trustees on behalf of the estates of APH and the Parsons, thereby releasing APHs and the Parsons claims against Defendants. (Id. at 13, 15.) At the December 5, 2011 hearing on the Motion to Dismiss, the Court was informed that the claims between Defendants and the Parsons and APH were released, and that the only claims remaining were that of Smith and Fitzgerald.

8

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 9 of 33 2387

PageID #:

Plaintiffs retained counsel Arnold Phillips, Esq., who made an oral motion to file an amended complaint. On December 6, 2011, the Court granted plaintiffs Smith and Fitzgerald leave to amend and denied Defendants Motion to Dismiss without prejudice.2 (Doc. # 48.) On January 19, 2012, Plaintiffs filed the present First Amended Complaint (FAC) against PSI and Mason. (FAC, Doc. # 56.) The FAC alleges the following claims: (1) Fraud (id. 8085); (2) Breach of Contract (id. 8689); and (3) Violation of HRS Chapter 480 (id. 9094). On March 5, 2012, Defendants filed a Motion to Dismiss First Amended Complaint, or, In the Alternative, For Summary Judgment (Defendants Motion). (Doc. # 59.) Defendants also filed a Concise Statement in Support of its Motion. (Doc. # 60.) On March 28, 2012, Plaintiffs filed an Opposition to Defendants Motion to Dismiss. Plaintiffs also filed a Concise Statement in Opposition. (Pls CSOF, Doc. # 68.) On April 4, 2012, Defendants filed a Reply in support of their Motion to Dismiss (Reply, Doc. # 72). On April 18, 2012, the Court heard Defendants

On December 23, 2011, APH and Defendants filed a Stipulation for Dismissal of Complaint with Prejudice as to Plaintiff Aloha Package Homes LLC. (Doc. # 53.) Also on December 23, 2011, Defendants and the Parsons filed a Stipulation for Dismissal of Complaint with Prejudice as to Plaintiffs Virginia Parsons and Dale J. Parsons, Jr. (Doc. # 54.)

9

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 10 of 33 2388

PageID #:

Motion, and on April 30, 2012, the Court issued an Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Defendants Motion (April 30 Order). (Doc. # 82.) On May 9, 2012, Plaintiffs filed the instant Motion for Reconsideration. (Mot for Recon, Doc. # 89.) Defendants filed an Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Reconsideration on May 23, 2012. (Defs Oppn, Doc. # 93.) On June 1, 2012, Plaintiffs filed a Reply in Support of the Motion for Reconsideration. (Pls Reply, Doc. # 95.) STANDARD OF REVIEW Reconsideration is permitted only on the following grounds: (a) discovery of new material facts previously not available; (b) intervening change in law; (c) manifest error of law or fact. See Local Rule 60.1; see also Sierra Club, Haw. Chapter v. City & Cnty. of Honolulu, 486 F. Supp. 2d 1185, 1188 (D. Haw. 2007) (Local Rule 60.1 explicitly mandates that reconsideration only be granted upon discovery of new material facts not previously available, the occurrence of an intervening change in law, or proof of manifest error of law or fact.). A motion for reconsideration must accomplish two goals. First, a motion for reconsideration must demonstrate reasons why the court should reconsider its prior decision. Second, a motion for reconsideration must set forth

10

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 11 of 33 2389

PageID #:

facts or law of a strongly convincing nature to induce the court to reverse its prior decision. Donaldson v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 947 F. Supp. 429, 430 (D. Haw. 1996); Na Mamo O Aha Ino v. Galiher, 60 F. Supp. 2d 1058, 1059 (D. Haw. 1999). Mere disagreement with a previous order is an insufficient basis for reconsideration, and reconsideration may not be based on evidence and legal arguments that could have been presented at the time of the challenged decision. See Haw. Stevedores, Inc. v. HT & T Co., 363 F. Supp. 2d 1253, 1269 (D. Haw. 2005). Whether or not to grant reconsideration is committed to the sound discretion of the court. Navajo Nation v. Confederated Tribes & Bands of the Yakima Indian Nation, 331 F.3d 1041, 1046 (9th Cir. 2003) (citing Kona Enter., Inc. v. Estate of Bishop, 229 F.3d 877, 883 (9th Cir. 2000)). A district court may reconsider its ruling on a motion for summary judgment at any time before final judgment is entered. United States v. Desert Gold Mining Co., 433 F.2d 713, 715 (9th Cir. 1970). Aside from these factors, a district court also has inherent authority to reconsider an interlocutory decision to prevent clear error or prevent manifest injustice. Christianson v. Colt Indus. Operating Corp., 486 U.S. 800, 817 (1988); c.f. United States v. Alexander, 106 F.3d 874, 876 (9th Cir.1997) (recognizing that district courts have discretion to depart from law of the case and reconsider a prior

11

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 12 of 33 2390

PageID #:

ruling, where, inter alia, the first decision was clearly erroneous, changed circumstances exist, or to avoid manifest injustice). In addition to the inherent power to modify a non-final order, Rule 54(b) authorizes a district court to revise a non-final order at any time before entry of a judgment adjudicating all the claims. Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b); see also Am. Cas. Co. of Reading, Pa. v. Kemper, 2009 WL 1651284, at *2 (D. Ariz. June 12, 2009); Am. Rivers v. NOAA Fisheries, 2006 WL 1983178, at *2 (D. Or. July 14, 2006). Under Rule 54(b) a district court can modify an interlocutory order at any time before entry of a final judgment. Credit Suisse First Boston Corp. v. Grunwald, 400 F.3d 1119, 1124 (9th Cir. 2005) (internal quotation marks omitted). DISCUSSION Plaintiffs request that the Court reconsider its April 30 Order on two grounds: (1) to review new evidence supporting a finding that Fitzgeralds Construction Contract is not a fixed-price contract; and (2) to review documents attached to the FAC that may have been inadvertently overlooked concerning the lien rights, profit structures of the contractors on their job breakout spreadsheet and Defendants bonding statements and exclusions designated in the Smith bonded construction contract which do not support a finding of a fixed price contract. (Mot. for Recon at 8.) The Court will address each contract separately.

12

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 13 of 33 2391

PageID #:

I.

Vineyard Project In the April 30 Order, the Court found that the construction contract

for Fitzgeralds project was a fixed-price contract and that Fitzgerald was therefore not entitled to any of the bonded funds. The Court dismissed Fitzgeralds fraud claim,3 and granted Defendants summary judgment as to Fitzgeralds breach of contract and UDAP claims to the extent that his claims for relief relate to the bonded funds. A. New Evidence Plaintiffs seek reconsideration of the finding that the Vineyard Construction Contract is a fixed-price contract and assert that reconsideration is supported by new evidencea signed January 9, 2008 addendum to the Vineyard Construction Contract (Martin Addendum) that Fitzgerald stated he located on May 1, 2012. (Mot. for Recon at 3.) Generally, a party moving for reconsideration on the basis of newly discovered evidence must show that the evidence (1) existed at the time of the trial, (2) could not have been discovered through due diligence, and (3) was of such magnitude that production of it earlier would have been likely to change the

The Court found that Plaintiffs failed to state a claim for fraud because they did not sufficiently allege the element of detrimental reliance.

13

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 14 of 33 2392

PageID #:

disposition of the case. Jones v. Aero/Chem Corp., 921 F.2d 875, 878 (9th Cir. 1990) (internal citations omitted). If the evidence was in the possession of the party before the judgment was rendered or if it could have been discovered with reasonable diligence, it is not newly discovered. Feature Realty, Inc. v. City of Spokane, 331 F.3d 1082, 1092 (9th Cir. 2003) (citations omitted); Caliber One Indem. Co. v. Wade Cook Fin. Corp., 491 F.3d 1079, 1085 (9th Cir. 2007). Defendants contend the evidence that Plaintiffs present was not previously unavailable to Plaintiffs before the Courts April 30 Order. (Defs Oppn at 69.) Plaintiffs explain that Fitzgeralds computer and hard drive crashed in April 2011, and that since then he had been unable to restore many of his documents although he had been diligently searching through his computer . . . for a signed copy of the Martin Addendum and other documents. (Mot. for Recon at 34.) Fitzgerald states that it was during a massive search on May 1, 2012 that by dumb luck he found the Martin Addendum. (Doc. # 95-1 16.) Virginia Parsons also states in an affidavit that she was unable to locate a signed copy of the Martin Addendum. (Doc. # 95-2.) As a preliminary matter, the Court finds the timing of Fitzgeralds discovery of the Martin Addendum somewhat suspect; Fitzgerald states that he found the Martin Addendum on May 1, 2012, one day after the Court issued its

14

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 15 of 33 2393

PageID #:

Order. (Mot. for Recon at 3.) Plaintiffs also have not explained why they could not have previously obtained a copy of the Martin Addendum from contractor Thomas Martin, who was a party to the addendum. However, a courts determination that an evidentiary proffer is not newly-discovered does not foreclose it from exercising its discretion and reconsidering its prior ruling. All rulings of a trial court are subject to revision at any time before the entry of judgment. United States v. Houser, 804 F.2d 565, 567 (9th Cir. 1986) (quoting Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b)); see also Abada v. Charles Schwab & Co., 127 F. Supp. 2d 1101, 1102 (S.D. Cal. 2001) (stating that a court has the discretion to reconsider and modify an interlocutory decision for any reason it deems sufficient, even in the absence of new evidence or an intervening change in or clarification of controlling law.). The Court notes that Defendants do not challenge the validity of the Martin Addendum. More importantly, the Court finds that the proffered Martin Addendum to the Vineyard Contract clearly contradicts Defendants theory that the Vineyard Contract was a fixed-price contract under which Fitzgerald, as Owner, was not entitled to any surplus of the bonded funds. Therefore, to avoid manifest injustice, the Court will consider the Martin Addendum in support of Plaintiffs Motion for Reconsideration.

15

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 16 of 33 2394

PageID #:

B.

Vineyard Construction Contract Contract terms should be interpreted according to their plain,

ordinary, and accepted meaning. Found. Intl, Inc. v. E.T. Ige Constr., Inc., 102 Hawaii 487, 78 P.3d 23, 30-31 (2003). Under Hawaii law, a contract must be reviewed in its entirety and the courts principle objective is to ascertain and effectuate the intent of the parties as manifested by the entire contract. Brown v. KFC Natl Mgmt. Co., 82 Hawaii 226, 921 P.2d 146, 160 (1996) (citing Univ. of Hawaii Prof'l Assembly v. Univ. of Hawaii, 66 Haw. 214, 659 P.2d 720, 724 (1983)). If there is doubt, the interpretation which most reasonably reflects the intent of the parties must be chosen. Id. Ambiguity exists only when the contract taken as a whole is reasonably subject to differing interpretation. County of Kauai v. Scottsdale Ins. Co., Inc., 90 Hawaii 400, 978 P.2d 838, 844 (1999) (citation omitted). Where the language of a contract is ambiguous, so that there is some doubt as to the intent of the parties, that intent is a question of fact. Bishop Trust Co., Ltd. v. Cent. Union Church of Honolulu, 3 Haw. App. 624, 656 P.2d 1353, 1356 (1983) (citing DiTullio v. Hawaiian Ins. & Guar. Co., Ltd., 1 Haw. App. 149, 616 P.2d 221 (1980)). When the contract language is ambiguous, parol evidence of the parties intent may be considered. Amfac, Inc. v. Waikiki Beachcomber Inv. Co., 74 Haw. 85, 839 P.2d 10, 31 (1992).

16

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 17 of 33 2395

PageID #:

The Courts April 30 Order found that the Vineyard Construction Contract was a fixed-price contract because it provided that the contractor would be paid an ultimate sum to cover the total cost of the project4 and because the contract does not reference a rate of profit for the contractor, as would be the case with a cost-plus contract. The Court determined that Fitzgerald was therefore not entitled to any of the bonded funds and that he thus cannot claim that he suffered an injury with respect to those funds. The Martin Addendum to the Vineyard Construction Contract, however, indicates that the contractor contracted to perform only a portion of the project and receive only part of the bonded funds. The Martin Addendum also provides that Fitzgerald and Parsons as Owners, among others, are to provide building materials and certain projects. (Martin Addendum, Mot. for Recon Ex.

The Vineyard Construction Contract reads, in pertinent part:

That for and in consideration of the payments hereafter mentioned, Contractor hereby covenants and agrees with Owner to furnish and pay for all material, and all labor, equipment, water, power, and all other items necessary for the completion of [the Vineyard Project] . . . For and in consideration of the covenants, undertakings and agreements of Contractor herein set forth, and upon the full and faithful performance thereof by Contractor, Owner hereby agrees to pay Contractor the sum of ($392,599.00) in lawful money[.] (Doc. # 60-3.)

17

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 18 of 33 2396

PageID #:

1.) The Martin Addendum, entitled Addendum to Contract and Job Cost Breakdown, is signed by contractor Thomas Martin, and Virginia Parsons and Fitzgerald, and states in relevant part: Virginia Parsons and Timothy Fitzgerald (Owners) and Thomas A. Martin (Contractor) agree that the Owners, Pacific Source and Aloha Package Homes will provide the building materials and specific projects (stated below) for 2276 Vineyard St., Wailuku HI 96793 and that the Contractors contracted portion of the overall bonded construction project of $392,599 is $234,561 (see attached Contractors Proposal). (Id.) The Martin Addendum, dated January 9, 2008, after the original Vineyard Construction Contract was signed, also lists a number of [e]xclusions from the Contractors contract agreement, such as grading, appliances, and labor for finish carpentry. (Id.) The Martin Addendum indicates that the contractor did not, and was not intended to, receive the entire sum of the bonded funds and that Fitzgerald, as an Owner, is not necessarily precluded as a matter of law from receiving any unused funds. In other words, to the extent that Defendants argued that Fitzgerald contracted to have the Vineyard Project constructed for a fixed price such that any unused funds belong only to the general contractor, the Martin Addendum demonstrates otherwise. Therefore, in considering the Martin Addendum with the Vineyard

18

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 19 of 33 2397

PageID #:

Construction Contract, the Court finds that the addendum creates an ambiguity as to whether any unused bonded funds belong only to the general contractor. The Court next conducts a further inquiry to determine the intention of the parties. See Maui Land & Pineapple Co. v. Dillingham Corp., 67 Haw. 4, 11, 674 P.2d 390, 395 (1984). Defendants have not met their initial burden of showing the absence of any genuine issue of material fact. See T.W. Elec. Serv., Inc. v. Pacific Elec. Contractors Assn, 809 F.2d 626, 630 (9th Cir. 1987). Specifically, Defendants have not provided any evidence that the parties to the Vineyard Construction Contract intended that the contract be a fixed-price contract. Defendants have thus not carried their summary judgment burden of establishing that the Vineyard Construction Contract is a fixed-price contract. In their Opposition to the Motion for Reconsideration, Defendants argue that the Martin Addendum does not materially affect the case. For example, Defendants argue that Pacific Source did not sign or otherwise ratify in writing the Martin Addendum, and was not a party to the Martin Addendum, which post-dated the Construction Contract and Performance Bond. Therefore, according to Defendants, such changes are not covered by the bond and do not impose duties or obligations upon Pacific Source. (Oppn at 10.) The Court is not persuaded. The issue here is not what Defendants

19

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 20 of 33 2398

PageID #:

duties or obligations were, but rather whether any monies saved or cost overruns from the Vineyard Project would inure to the benefit or detriment of only the general contractor and not Fitzgerald. In other words, the issue is whether, as a matter of law, Fitzgerald is precluded from asserting any injury resulting from Defendants alleged misconduct. Whether the Martin Addendum was signed or ratified in writing by Defendants is of no consequence to this limited issue. Moreover, the crux of Plaintiffs FAC focuses on Defendants alleged actions with regard to disbursement of the bonded funds, not on Defendants obligation as surety to complete the Vineyard and Smith Projects in the event the contractors defaulted. Defendants also argue that to the extent that the Martin Addendum reflects that Fitzgerald may have subcontracted to be a materials provider for the Vineyard Project, apart from and in addition to his role as owner, Fitzgerald has no right to payment under the bond, which was a performance bond rather than a payment bond. (Oppn at 1011.) This argument does not help Defendants. Again, Defendants appear to narrow the focus of the issue strictly to Pacific Sources obligation to complete the project if the contractor defaults, when

20

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 21 of 33 2399

PageID #:

Plaintiffs complain about Defendants disbursement of the bonded funds.5 Defendants note that, as the Court found, the Vineyard Construction Contract does not contain a provision concerning commissions owed to the contractor, but only includes fixed-price language. (Oppn at 17.) Defendants point out that the Martin Addendum does not provide for a commission or a flexible cost-plus reimbursement rate for the contractor. However, what the Martin Addendum does indicate is that the contractor was not entitled to all of the bonded funds slated for the Vineyard Project and that Fitzgerald, among others, was to provide building materials and complete certain parts of the project. Thus, the Martin Addendum creates an ambiguity as to whether Fitzgerald was entitled to recover any surplus of the bonded funds.6

Moreover, the Martin Addendum does not establish that Fitzgerald is subcontractor, given that the Martin Addendum provides that the contractor is only responsible for part of the construction project, with Fitzgerald and others not only providing materials but completing certain segments of the project that are excluded from the contractors agreement. (See Doc. # 89-2 at 12.) Plaintiffs also argue that the Martin Addendum is supported by the Defendants bonding statements. Specifically, Plaintiffs point to line-item costs pertaining to labor and foundation work in Defendants January 31, 2008 bonding statement that total $234,561, the same figure that the contractor was to receive pursuant to the Martin Addendum. Although these documents were included in the record, Plaintiffs did not previously point this out to the Court. In any event, the Court need not reach this issue in light of the Courts finding.

21

6

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 22 of 33 2400

PageID #:

III.

Fitzgeralds Claims In the April 30 Order, the Court determined that because the

construction contract for the Vineyard Project was a fixed-price contract, Fitzgerald could not claim as a matter of law that he suffered an injury with respect to those funds. Because the Court now determines that Fitzgerald is not precluded from asserting some entitlement to the bonded funds, the Court reexamines Fitzgeralds claims. A. Fraud As stated in the April 30 Order, the FAC does not sufficiently allege, beyond conclusory allegations, how Plaintiffs relied on Defendants alleged misrepresentations. Moreover, to the extent that Plaintiffs argue in their Opposition to Defendants Motion and Plaintiffs Motion for Reconsideration that they reasonably relied on Defendants alleged contractual promises to act in a fiduciary capacity, this argument fails. First, Plaintiffs fraud claim, as pled in the FAC, is based on alleged misrepresentations on statements, checks, invoices, and other records, not on Defendants alleged promise to act as a fiduciary. Therefore, Plaintiffs alleged reliance on any promises to act as a fiduciary is distinct from the fraud claim in the FAC. Second, contractual promises generally cannot form the basis of a fraud claim. Although a promise made without the present intent to

22

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 23 of 33 2401

PageID #:

fulfill the promise is actionable as fraud, Eastern Star, Inc. v. Union Bldg. Materials Corp., 712 P.2d 1148, 1159 (Haw. Ct. App. 1985), the Hawaii Supreme Court has stated that, as a general rule, fraud cannot be predicated on statements which are promissory in their nature, or constitute expressions of intention, and an actionable representation cannot consist of mere broken promises, unfulfilled predictions or expectations, or erroneous conjectures as to future events, even if there is no excuse for failure to keep the promise, and even though a party acted in reliance on such promise. Stahl v. Balsara, 587 P.2d 1210, 1214 (1978) (citations omitted). In the instant Motion for Reconsideration, Plaintiffs cite Hawaii Revised Statutes 444-25.5, which requires contractors to explain verbally in detail, inter alia, the homeowners option to demand bonding on the project and how the bond would protect the homeowner. Plaintiffs argue that under section 444-25.5, Plaintiffs would have received an explanation of the protections afforded by bonding and thus had a right to rely upon the bond to protect them and expect that the Defendants as surety would not fraudulently misuse construction funds. Plaintiffs argument based on this statute is not clear. To the extent that Plaintiffs are seeking to maintain their fraud claim, this is a new argument that could have been raised in the earlier proceedings and is thus not appropriate in a

23

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 24 of 33 2402

PageID #:

motion for reconsideration. See Wereb v. Maui County, 830 F. Supp. 2d 1026, 1031 (D. Haw. 2011) (reconsideration may not be based on . . . legal arguments that a movant could have presented at the time of the challenged decision) (citing Kona Enter., Inc. v. Estate of Bishop, 229 F.3d 877, 890 (9th Cir. 2000). Moreover, even if the Court were to consider this argument, it would fail. First, as stated above, the FACs allegations of fraud do not include Defendants alleged promises to act as a fiduciary, and promises based on future events generally cannot form the basis of fraud. Moreover, Plaintiffs argument pertains to the representations of the contractors, rather than that of Defendants. (See Mot. for Recon at 16 (Thereby, Plaintiffs reasonably relied upon the contractors representation regarding the protection of their construction funds and agreed to contract with the bonding entity.).) Thus, to the extent that Plaintiffs seek reconsideration of the Courts determination as to the sufficiency of their fraud claim, the Court denies Plaintiffs Motion. The Court, however, recognizes that it may be possible for Plaintiffs to state a claim if provided the opportunity to amend this claim. Therefore, Fitzgeralds fraud claim is DISMISSED WITHOUT PREJUDICE with leave to

24

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 25 of 33 2403

PageID #:

amend no later than thirty (30) days from the filing of this Order.7 Failure to do so and to cure the pleading deficiencies may result in dismissal of the claim with prejudice. 2. Breach of Contract

Defendants assert that PSIs duties to Fitzgerald and Smith were limited to those described in the Vineyard and Smith Performance Bond, which were contingent on the default of the general contractor. (Defs Memo, Doc. # 59-1 at 79.) Thus, according to Defendants, because the general contractors performed under the Vineyard and Smith Construction Contracts, the condition precedent that would have given rise to PSIs duties under the Performance Bond did not occur, and Plaintiffs have failed to state a claim. (Id. at 2122, 2627.) Defendants also assert that Plaintiffs, in their capacities as owners of the projects, suffered no damages. (Defs Memo at 9.) Plaintiffs allege that PSI breached its obligations under the Fitzgerald and Smith Uniform Performance Bonds, Assignments of Contract and Agreement Bonds when it mismanaged the outlay of payments by disbursing payments relating to the Fitzgerald and Smith projects to improper, unauthorized debts and

The Court also takes the opportunity to clarify that the Court grants Plaintiffs leave to amend their fraud claim as to Smith as well.

25

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 26 of 33 2404

PageID #:

invoices[.] (FAC 87 88.) Plaintiffs state that they are not suing upon the performance bond as it would relate to quality of construction. (Oppn at 4.) They assert that PSI was obligated and bound unto Plaintiffs to act as surety to distribute funds according to the construction contracts. (Pls CSOF in Oppn No. 6.) Plaintiffs, however, have failed to allege all of the basic elements of a breach of contract claim. Specifically, the FAC fails to identify the particular provision of a contract allegedly breached by Defendants. See Velez v. The Bank of N.Y. Mellon, 2011 WL 572523, at *3 (D. Haw. Feb. 15, 2011) (explaining elements of breach of contract claim); Otani v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., 927 F. Supp. 1330, 1335 (D. Haw. 1996) (In breach of contract actions, [ ] the complaint must, at minimum, cite the contractual provision allegedly violated. Generalized allegations of a contractual breach are not sufficient.). In opposition to Defendants Motion, Plaintiffs point to a provision under the General Conditions section of the Vineyard Construction Contract which states: BOND: Before commencing work, Contractor shall furnish a performance and payment bond in an amount equal to one hundred per cent (100%) of the contract price. (Plaintiffs CSOF in Oppn No. 6.) However, insofar as Plaintiffs argue that a requirement in the construction contract calling for

26

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 27 of 33 2405

PageID #:

a performance and payment bond converts the bond into a payment bond, this theory fails. See Johns-Manville Sales Corp. v. Reliance Ins. Co., 410 F.2d 277, 27879 (9th Cir. 1969) (stating that when an underlying contract requires a performance and payment bond and only a performance bond is furnished, the mere fact that such bond incorporates the contract does not convert the performance bond into a payment bond). Because it may be possible for Plaintiffs to state a claim, Fitzgeralds breach of contract claim is DISMISSED WITHOUT PREJUDICE with leave to amend no later than thirty (30) days from the filing of this Order. 3. H.R.S. Chapter 480

The Hawaii Unfair and Deceptive Trade Practices Act states that any person who is injured in the persons business or property by reason of anything forbidden or declared unlawful by this chapter . . . [m]ay sue for damages sustained by the person, including treble damages, and [m]ay bring proceedings to enjoin the unlawful practice. Haw. Rev. Stat. 48013(a)(1), (2). Section 48013 of the Hawaii Revised Statutes establishes four essential elements: (1) a violation of chapter 480; (2) injury to plaintiffs business or property resulting from such violation; (3) proof of the amount of damages; and (4) a showing that the action is in the public interest or that the defendant is a merchant. Davis v. Four Seasons

27

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 28 of 33 2406

PageID #:

Hotel Ltd., 122 Hawaii 423, 228 P.3d 303, 335 (2010). Section 480-2 provides that [u]nfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in the conduct of any trade or commerce is unlawful. Id. 4802(a). A practice is unfair when it offends established public policy and when the practice is immoral, unethical, oppressive, unscrupulous or substantially injurious to consumers. Balthazar v. Verizon Hawaii, Inc., 109 Hawaii 69, 123 P.3d 194, 202 (2005). An act is deceptive when it has the capacity or tendency to mislead or deceive. Courbat v. Dahana Ranch, Inc., 111 Hawaii 254, 141 P.3d 427, 434 (2006). Whether a practice is deceptive or unfair is ordinarily a question of fact. Balthazar, 123 P.3d at 197 n.4. Plaintiffs allege that PSIs actions, including its accounting and billing practices, are unfair or deceptive acts or practices under chapter 480 and that such actions resulted in Plaintiffs suffering financial loss. (FAC 9193.) Defendants contend that there was no privity of contract between PSI and Plaintiffs with respect to the alleged financial records and communications. However, a contractual relationship is not a required element of a UDAP claim. See State by Bronster v. U.S. Steel Corp., 82 Hawaii 32, 919 P.2d 294, 314 (1996). The Court notes Plaintiffs argument that Defendants never produced a full reconciliation of the Fitzgerald and Smith projects bonded accounting.

28

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 29 of 33 2407

PageID #:

Since there appears to remain some outstanding discovery issues in this case and to the extent that certain of Plaintiffs claims are not adequately pled, the Court finds a ruling on summary judgment to be premature. Defendants Motion to Dismiss, or in the Alternative, For Summary Judgment is therefore DENIED WITHOUT PREJUDICE. II. Smith Project In the April 30 Order, the Court found that the Smith construction contract was a fixed-price contract. The Court, however, determined that Defendants Motion for Summary Judgment as to Smith was premature because the record was not adequately developed as to Smiths accounting of funds. Accordingly, the Court denied without prejudice Defendants Motion as to Smiths breach of contract and UDAP claims. The Court also dismissed Plaintiffs fraud claim without prejudice as to Smith. In the instant Motion for Reconsideration, Plaintiffs argue that the construction contract for the Smith Project was not a fixed-price contract. Plaintiffs argue, inter alia, that the Smith Construction Contract has a list of exclusions indicating that the contractor is not completing the entire project to the point of readiness and that Defendants bonding statements show that the contractor in the Smith Project agreed to specific profit figures. (Mot. for Recon at

29

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 30 of 33 2408

PageID #:

912.) The Court does not find Plaintiffs arguments persuasive. First, as Defendants argue, a list of exclusions in the contract does not preclude the agreement from being a fixed-price contract because parties can enter into fixedprice contracts to construct buildings to any level of completion. Second, that the bonding statement includes a profit figure as part of the overall contract amount does not preclude a finding that it is a fixed-price contract. Upon careful review of the Smith construction contract, however, the Court finds an ambiguity as to whether the contract is a fixed-price contract such that Smith would be precluded from a return of any unused bonded funds. The Smith Construction Contract defines Lehua as the Contractor as hired by the Owner, to build a custom home and provides, in relevant part: That for and in consideration of the payments hereinafter mentioned, the Contractor hereby covenants and agrees with Owner to furnish a bond and manage payments for all materials, and to pay Contractor and/or Contractors subcontractors for all labor, equipment, water, power, and all other items necessary for the completion of in accordance with the Plans and Specifications which are identified by the signatures of the parties hereto. ... For and in consideration of the covenants, undertakings and agreements herein set forth, and upon the full and faithful performance thereof by Contractor, Owner hereby agrees to pay Contractor through Contractors bonding entity, and Contractors bonding entity agrees to distribute, the sum of . . . $430,000.00 in lawful money, such amounts to be paid by the Owner or Owners Lender through the Contractors bonding entity, and distributed

30

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 31 of 33 2409

PageID #:

by Contractors bonding entity accordingly, as follows[.] (Doc. # 60-4 at 1 (emphasis added).) The contract then lists amounts to be paid at various stages of the project. The contract also provides that [t]he total construction cost includes an owner contingency/allowance fund of $32,565.00 for building materials as specified per the materials contract that Owner has agreed to supply. (Id.) The contracts provision of a contingency fund within the overall contract price conflicts with the theory that the contractor is to receive the entire sum of the funds without the possibility of any money being returned to Smith. Moreover, although the contract defines Lehua as hired by the Owner, to build a custom home, the contract does not clearly set forth that the contractor will provide materials; rather, the contract provides that the contractor will manage payments for all materials. Therefore, the Court finds that the contract is ambiguous because it can be reasonably interpreted as a fixed-price contract or a contract under which Smith is not precluded from recouping any unused funds. See Scottsdale Ins. Co., Inc., 978 P.2d at 844 (Ambiguity exists only when the contract taken as a whole is reasonably subject to differing interpretation.). Defendants have submitted the declaration of the Smith Project contractor, who stated that the Smith Construction Contract was a fixed-price contract, whereby Lehua contracted to build the Smith Project for the owners for

31

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 32 of 33 2410

PageID #:

the sum of $430,000. (Doc. # 60-2 6.) However, Plaintiffs have submitted Smiths and Virginia Parsons affidavits stating that the Smith Project contractor, Lehua, was to provide labor-only services for $282,693.00, and email correspondence with the subject line SMITH DRAWS in which the Smith Project contractor, in response to an inquiry from Virginia Parsons, appears to approve a total sum of $282,693.00 entitled LEHUA. (Docs. # 67-2, 67-3, 67-7.) The Court finds a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the Smith Construction Contract is a fixed-price contract that would preclude Smiths entitlement to any of the bonded funds. IV. Defendants Supplemental Statement On July 17, 2012, Defendants filed a Supplemental Statement in Opposition to the Motion for Reconsideration in light of the Courts recent decision to schedule a hearing on the Motion. Defendants request that the Court consider the Supplemental Statement to correct certain misstatements made by Plaintiffs which bear upon the limited issues remaining in this case. Specifically, Defendants provide a chart that they state breaks down each item in Smiths contingency/allowance fund and provides a reconciliation of the amount. Defendants attached exhibits that they state show that Pacific Source paid for the construction costs that Smith alleged he paid out of his own pocket.

32

Case 1:11-cv-00111-SOM-KSC Document 110 Filed 08/30/12 Page 33 of 33 2411

PageID #:

Plaintiffs filed a Reply to Defendants Supplemental Statement. In light of the Courts finding a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the Smith Construction Contract is a fixed-price contract, and to the extent that Defendants appear to have been able to raise these issues in the earlier proceedings and have not filed a Motion for Reconsideration, the Court declines to consider Defendants arguments at this time. CONCLUSION For the reasons stated above, the Court GRANTS IN PART and DENIES IN PART Plaintiffs Motion for Reconsideration (doc. # 89), and GRANTS IN PART and DENIES IN PART Defendants Motion to Dismiss First Amended Complaint, Or, In the Alternative, For Summary Judgment (doc. # 59). IT IS SO ORDERED. DATED: Honolulu, Hawaii, August 30, 2012.

_____________________________ David Alan Ezra United States District Judge

33

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- A K Chopra Solution Manual PDFDocument536 pagesA K Chopra Solution Manual PDFsharan3186% (73)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Letter of Ready Willing and Able (Rwa)Document1 pageThe Letter of Ready Willing and Able (Rwa)Deoo Milton Eximo100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

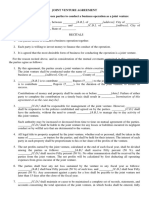

- Joint Venture AgreementDocument2 pagesJoint Venture Agreementpan RegisterNo ratings yet

- Unidroit PPT (Report - Group 2 Ibt)Document24 pagesUnidroit PPT (Report - Group 2 Ibt)Togz MapeNo ratings yet

- Volcker Rule Prohibition Sponsorship and InvestmentDocument35 pagesVolcker Rule Prohibition Sponsorship and InvestmentDeadlyClearNo ratings yet

- SASCO LBHI OpinionDocument15 pagesSASCO LBHI OpinionDeadlyClearNo ratings yet

- BraxtonDocument17 pagesBraxtonDeadlyClearNo ratings yet

- CHASE BARCODE United States Patent - 8688569Document22 pagesCHASE BARCODE United States Patent - 8688569DeadlyClearNo ratings yet

- ALASKA Daily Gov-Corp Bond FundDocument2 pagesALASKA Daily Gov-Corp Bond FundDeadlyClearNo ratings yet

- QL KZKFKCFMDocument377 pagesQL KZKFKCFMDeadlyClearNo ratings yet

- Mayer Steel Pipe Corp v. CADocument1 pageMayer Steel Pipe Corp v. CAJovelan V. EscañoNo ratings yet

- B45 Marvex Commercial Co. Inc. v. Petra Hawpia and Co., GR L-19297, 22 December 1966, en Banc, Castro (J) - CARINANDocument2 pagesB45 Marvex Commercial Co. Inc. v. Petra Hawpia and Co., GR L-19297, 22 December 1966, en Banc, Castro (J) - CARINANloschudentNo ratings yet

- Securities Law Contracts of GuaranteeDocument6 pagesSecurities Law Contracts of GuaranteesteNo ratings yet

- SBI MANDATE and NCNDADocument9 pagesSBI MANDATE and NCNDAsagar thakkarNo ratings yet

- Company ProfileDocument13 pagesCompany ProfileTerefe Gebremariam AregehagnNo ratings yet

- Contract of LaborDocument2 pagesContract of LaborRenz AmonNo ratings yet

- Business LawDocument12 pagesBusiness LawAnujeeth GopalNo ratings yet

- Agreement-Contract, Offer-AcceptanceDocument69 pagesAgreement-Contract, Offer-AcceptanceAbhinav PandeyNo ratings yet

- GUAGUA NATIONAL COLLEGES V GUAGUA FACULTY LABORDocument5 pagesGUAGUA NATIONAL COLLEGES V GUAGUA FACULTY LABORChap ChoyNo ratings yet

- Partnership Law Review QuestionsDocument5 pagesPartnership Law Review QuestionsBobby Olavides Sebastian0% (1)

- Loadstar Vs Malayan InsuranceDocument4 pagesLoadstar Vs Malayan InsuranceYodh Jamin OngNo ratings yet

- Dissolution of Firm Project ReportDocument19 pagesDissolution of Firm Project Reportkamdica86% (28)

- AOADocument19 pagesAOAsoundaryaNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis May 6, 2020Document2 pagesCase Analysis May 6, 2020Mark Kevin ArrocoNo ratings yet

- Subcontractor Affidavit With Waiver and Release2Document2 pagesSubcontractor Affidavit With Waiver and Release2cheNo ratings yet

- General Form For Registration of SecuritiesDocument10 pagesGeneral Form For Registration of SecuritiesblcksourceNo ratings yet

- Hylomar 800 ML TinsDocument1 pageHylomar 800 ML TinsProject Sales CorpNo ratings yet

- Contracts ChecklistDocument3 pagesContracts ChecklistSteve WatmoreNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 - Formation of A CompanyDocument8 pagesUnit 7 - Formation of A CompanyRosemary PaulNo ratings yet

- Primelink Properties vs. Ma. Clariza Lazatin-MagatDocument1 pagePrimelink Properties vs. Ma. Clariza Lazatin-MagatValora France Miral AranasNo ratings yet

- Construction Agreement - TemplateDocument11 pagesConstruction Agreement - TemplateQueencel SegunialNo ratings yet

- Law of Contracts II PDFDocument6 pagesLaw of Contracts II PDFNidhi PrakritiNo ratings yet

- Construction Law: With Assoc Prof Christopher Chuah and Assoc Prof Ian de VazDocument3 pagesConstruction Law: With Assoc Prof Christopher Chuah and Assoc Prof Ian de VazsckchrisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Incoterms and ContractsDocument46 pagesChapter 2 - Incoterms and Contracts48. Lê Nguyễn Anh ThưNo ratings yet

- Ind Assg Trade HazimDocument7 pagesInd Assg Trade HazimHazim HafizNo ratings yet

- Free ConsentDocument5 pagesFree ConsentHeart ToucherNo ratings yet