Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Final - Retallack

Final - Retallack

Uploaded by

MachubuCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Community Engagement, Solidarity, and Citizenship MODULE - QUARTER 1 - BERNADETTeDocument28 pagesCommunity Engagement, Solidarity, and Citizenship MODULE - QUARTER 1 - BERNADETTeBernadette Reyes100% (6)

- Deschooling Society Ivan IllichDocument6 pagesDeschooling Society Ivan IllichAmannNo ratings yet

- Stronger Water Utilities To Confront Commig Threats - 1aug23Document33 pagesStronger Water Utilities To Confront Commig Threats - 1aug23Eco H2ONo ratings yet

- MWM Water Discussion PaperDocument17 pagesMWM Water Discussion PaperGreen Economy CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Water Poverty IndexDocument21 pagesEnhancing Water Poverty IndexResearchteam2014No ratings yet

- Social AlternativesDocument53 pagesSocial AlternativesfungedoreNo ratings yet

- Sociology 2Document10 pagesSociology 2Mohd SaqibNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document16 pagesChapter 2Mesfin Mamo HaileNo ratings yet

- Smith 2015Document7 pagesSmith 2015Richard Solis ToledoNo ratings yet

- For Environmental Decision-Support Systems: Agent-Based ModelingDocument72 pagesFor Environmental Decision-Support Systems: Agent-Based ModelingTran SangNo ratings yet

- GWP - Social Equity and Integrated Water Resources Management - 2011Document88 pagesGWP - Social Equity and Integrated Water Resources Management - 2011nicolasbujakNo ratings yet

- PahlWostl - Integrated Water MGMNTDocument22 pagesPahlWostl - Integrated Water MGMNTjunkchanduNo ratings yet

- Addressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFDocument22 pagesAddressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFGino MontenegroNo ratings yet

- 17 Complexity Integrated Resources ManagementDocument9 pages17 Complexity Integrated Resources ManagementSarafanMalekNo ratings yet

- Water InternationalDocument10 pagesWater Internationalirina_madalina2000No ratings yet

- International Journal of Water Resources DevelopmentDocument14 pagesInternational Journal of Water Resources DevelopmentrycandraNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Social Learning in Restoring The Multifunctionality of Rivers and FloodplainsDocument14 pagesThe Importance of Social Learning in Restoring The Multifunctionality of Rivers and FloodplainsAdji KrisbandonoNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Economics and Environmental Policy DesignDocument12 pagesBehavioural Economics and Environmental Policy DesignKartik KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Natural Resource ManagementDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Natural Resource Managementogisxnbnd100% (1)

- Biodiversity at The Heart of Accounting For Natural Capital Paper July 2016 Low ResDocument13 pagesBiodiversity at The Heart of Accounting For Natural Capital Paper July 2016 Low ResewnjauNo ratings yet

- Sustainability in The Water Energy Food NexusDocument11 pagesSustainability in The Water Energy Food NexusAntoiitbNo ratings yet

- Lo RETHINKINGWATERGOVERNANCE 2017Document27 pagesLo RETHINKINGWATERGOVERNANCE 2017varshanimpi0214No ratings yet

- Smart Water Management - 2-1Document37 pagesSmart Water Management - 2-1Vishal S SonuneNo ratings yet

- The Renewable Energy Transition Realities For Canada and The World 1St Ed 2020 Edition John Erik Meyer Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Renewable Energy Transition Realities For Canada and The World 1St Ed 2020 Edition John Erik Meyer Full Chapterrobert.prevatte420100% (7)

- Kneese (1971) - Environmental Pollution, Economics and PolicyDocument15 pagesKneese (1971) - Environmental Pollution, Economics and PolicyLujan GNo ratings yet

- Water Allocation MethodsDocument43 pagesWater Allocation MethodsGabriel VeraNo ratings yet

- Water Resource Management PDFDocument47 pagesWater Resource Management PDFvandah7480No ratings yet

- The Moral Hazards of Smart Water ManagementDocument10 pagesThe Moral Hazards of Smart Water ManagementEfrizal Adil LubisNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledMohd SaqibNo ratings yet

- The Natural Capital Framework For Sustainably Efficient and Equitable Decision Making.Document8 pagesThe Natural Capital Framework For Sustainably Efficient and Equitable Decision Making.elise callerisaNo ratings yet

- Climate FinanceDocument12 pagesClimate FinanceVinícius SantiagoNo ratings yet

- 2012 Book SustainabilityScienceDocument447 pages2012 Book SustainabilityScienceSrishti PandeyNo ratings yet

- 2007 TotalWaterManagement SampleDocument18 pages2007 TotalWaterManagement SampleBogdan PopaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Management Literature Reviewc5ppm3e3100% (1)

- ECN350 Group AssignmentDocument14 pagesECN350 Group AssignmentMubashwara MehzabeenNo ratings yet

- Hamannetalchapterin ALSbookDocument40 pagesHamannetalchapterin ALSbookvardanNo ratings yet

- CirclesDocument11 pagesCirclesAnonymous UrzdtCB0INo ratings yet

- Assessing The Capacity To Govern Flood Risk in CitDocument20 pagesAssessing The Capacity To Govern Flood Risk in Citrais wrfNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 (Litrature Review) 21Document21 pagesChapter 2 (Litrature Review) 21Rushikesh PatilNo ratings yet

- System Complexity and Policy Integration ChallengesDocument14 pagesSystem Complexity and Policy Integration ChallengesJosé Eduardo ViglioNo ratings yet

- ICRE BrochureDocument10 pagesICRE BrochureBala Subramanian R RCBSNo ratings yet

- Abstract Inglés - Simposio Cambio ClimáticoDocument5 pagesAbstract Inglés - Simposio Cambio ClimáticoAgua SustentableNo ratings yet

- DDI11 SS Consumption KDocument19 pagesDDI11 SS Consumption KEvan JackNo ratings yet

- Globalization and EnvironmentalDocument24 pagesGlobalization and EnvironmentalPablo ChanNo ratings yet

- Thesis Climate Change PDFDocument9 pagesThesis Climate Change PDFzseetlnfg100% (2)

- 2014 Book GlobalizedWater-1Document303 pages2014 Book GlobalizedWater-1Daniel NaroditskyNo ratings yet

- TEEB Foundations Ecology and EconomicsDocument422 pagesTEEB Foundations Ecology and EconomicsTarcisioTeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Q3Document3 pagesQ3haikal MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Relevant Legal Frameworks Applicable To Climate ChangeDocument13 pagesRelevant Legal Frameworks Applicable To Climate ChangeanniejamesNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Document4 pagesEthics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Nethaji BKNo ratings yet

- GATsGovernanceDimensionAnalysis PDFDocument4 pagesGATsGovernanceDimensionAnalysis PDFFai RitzNo ratings yet

- The Drivers of Corporate Water Disclosure in Enhancing Information TransparencyDocument14 pagesThe Drivers of Corporate Water Disclosure in Enhancing Information TransparencyDesa PonggokNo ratings yet

- Iisa PaperDocument13 pagesIisa PaperSanatNo ratings yet

- Pedro & CastroDocument5 pagesPedro & CastrojmcastrobNo ratings yet

- Green Economy: Personal Tools NetworksDocument52 pagesGreen Economy: Personal Tools NetworksMihaela Leasă-LixandruNo ratings yet

- Red Group Module 3 AcitivityDocument8 pagesRed Group Module 3 AcitivityJet GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Concept of Sustainable DevelopmentDocument4 pagesConcept of Sustainable DevelopmentSidharth S PrakashNo ratings yet

- Flows 12Document3 pagesFlows 12jeancarlorodNo ratings yet

- Assessment Task 1 Issue SummaryDocument7 pagesAssessment Task 1 Issue SummaryManuel Pozos HernándezNo ratings yet

- Efficient Water AllocationDocument52 pagesEfficient Water AllocationEnoch ArdenNo ratings yet

- New Paradigms of Sustainability in the Contemporary EraFrom EverandNew Paradigms of Sustainability in the Contemporary EraRoopali SharmaNo ratings yet

- Environmental and Energy Policy and the Economy: Volume 2From EverandEnvironmental and Energy Policy and the Economy: Volume 2Matthew J. KotchenNo ratings yet

- Sociology (Midterm)Document8 pagesSociology (Midterm)John Aztex100% (2)

- Research and Development in Nigeria's Tertiary Institutions: Issues, Challenges and Way ForwardDocument9 pagesResearch and Development in Nigeria's Tertiary Institutions: Issues, Challenges and Way ForwardInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 5SSPP236 New Political Economy of The Media - Notes Moore: Martin - Moore@kcl - Ac.uk 1Document9 pages5SSPP236 New Political Economy of The Media - Notes Moore: Martin - Moore@kcl - Ac.uk 1Karissa ShahNo ratings yet

- Concepts and Perspective of CommunityDocument110 pagesConcepts and Perspective of CommunityJohn Leandro ReyesNo ratings yet

- Paper - Digital Economy and Development Research AgendaDocument17 pagesPaper - Digital Economy and Development Research AgendahandoutNo ratings yet

- Full Project Documentation From Group - 15 StudentsDocument104 pagesFull Project Documentation From Group - 15 StudentsGetachew Yizengaw EnyewNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Questions Part 1Document26 pagesSocial Studies Questions Part 1hyuck's sunflowerNo ratings yet

- Institutional Graduate Outcomes and Program Graduate OutcomeDocument14 pagesInstitutional Graduate Outcomes and Program Graduate OutcomeRoNnie RonNieNo ratings yet

- Concept of State and NationDocument54 pagesConcept of State and NationGaurav Tripathi100% (1)

- Logic of Consequences vs. Logic of Appropriateness Institutional DesignDocument27 pagesLogic of Consequences vs. Logic of Appropriateness Institutional Designziad_achkarRWU100% (1)

- Undp-Cb Social Cohesion Guidance - Conceptual Framing and ProgrammingDocument76 pagesUndp-Cb Social Cohesion Guidance - Conceptual Framing and ProgrammingGana EhabNo ratings yet

- 2012 PRATES R Cooperation in The Prisoners DilemmaDocument11 pages2012 PRATES R Cooperation in The Prisoners DilemmagabrielafrigolemeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 7 Vids 1 3 SS 1DDocument27 pagesChapter 1 7 Vids 1 3 SS 1DYuan Carlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Human Rights - UN Protection of Human RightsDocument18 pagesHuman Rights - UN Protection of Human RightsKiana Porras100% (1)

- II Bauböck 2006Document129 pagesII Bauböck 2006OmarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document23 pagesChapter 3Abhijeet BhagavatulaNo ratings yet

- A2 Deviance FunctionalismDocument18 pagesA2 Deviance FunctionalismTricia TriciaNo ratings yet

- Social Science PerspectivesDocument2 pagesSocial Science PerspectiveshenokNo ratings yet

- Avelino Et Al - 2019 - Transformative Social InnovationDocument12 pagesAvelino Et Al - 2019 - Transformative Social InnovationJessica PerezNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics in Philippine PerspectiveDocument18 pagesBusiness Ethics in Philippine PerspectiveANDELYN100% (1)

- Chappell - 2010 - Comparative Gender and Institutions Directions For ResearchDocument8 pagesChappell - 2010 - Comparative Gender and Institutions Directions For Research백미록(사회과학대학 여성학과)No ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication A Current PerspectiveDocument21 pagesIntercultural Communication A Current PerspectiveJody ManggalaningwangNo ratings yet

- Issues of Strategic Implementation in Higher Educa PDFDocument28 pagesIssues of Strategic Implementation in Higher Educa PDFDanielNo ratings yet

- Edu 413Document132 pagesEdu 413Adegbosin ToluNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Urban Community Development: A Case Study From The Perspective of Self-Governance and Public ParticipationDocument15 pagesSustainable Urban Community Development: A Case Study From The Perspective of Self-Governance and Public ParticipationSAHANANo ratings yet

- Politics and Social Organization: (Group 7)Document9 pagesPolitics and Social Organization: (Group 7)Lu CelNo ratings yet

- Peacebuilding in Deeply Divided SocietiesDocument350 pagesPeacebuilding in Deeply Divided SocietiesGudeta KebedeNo ratings yet

- Sociology Exam NotesDocument38 pagesSociology Exam NotesMaria PNo ratings yet

Final - Retallack

Final - Retallack

Uploaded by

MachubuOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Final - Retallack

Final - Retallack

Uploaded by

MachubuCopyright:

Available Formats

Policy Institutions and Processes PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions Professor Bienefeld

Final Term Paper April 24, 2012

Matthew Retallack ID# 100863468

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

The role of economics in my future thesis research is a central one and as I have discovered through the course of this first year, and in this course in particular, that role is much larger and more multidimensional than I had originally thought, with new dimensions emerging while others take on a distinctly economic character.

The ideas that guide my research are rooted both in technical challenges and in the confluence of the policy and practice of water resources management. Following Bachelors and Masters programmes in Civil Engineering I shifted my focus away from the technical specifics of design toward the management challenges associated with selecting appropriate technology; the policy side of water resources management. Over the course of six years and through numerous large, high-level multi-stakeholder consultations a number of key shifts in water management became evident. There is a need to manage water resources within watersheds; to move from governments to governance; and to move away from regulation toward shared responsibility (Polution Probe, 2011). This will involve an increased role for the public, requiring access to decision making as well as information, in addition to a reconfiguration of existing institutional structures.

These needed changes in how decisions are informed and made are compounded by concerns over the sustainability of our natural resources, with many regions in Canada, and certainly internationally, experiencing real and occasionally severe water stress. Although some of the effects of such a condition, such as drought and related impacts on

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

agriculture or municipal water supplies, are immediately identifiable, the full costs to society are not. This is due to the fact that water-based ecosystem services upon which societal and economic goals depend, these ecological factors of production, are not typically valued. As such they are generally invisible within quantitative decision making processes and indeed the nature of the relationships between societys goals and objectives, including economic activity, and the water-based ecosystem services upon which these activities to a greater or lesser extent depend, remain largely undefined in specific terms.

Thus in addition to a need to recast the institutions of water governance there is a fundamental need to understand how our interests are underpinned by ecological factors. This encompasses the broader role of economics within my research.

My current working title is An Economic Risk Management Approach to Promoting Sustainable Watershed Ecosystems. The essential idea is, that if the relationships between key social and economic goals, and the ecosystem services that support their realisation, can be characterised, then it will be possible to apply various risk scenarios to this framework of interconnected goals and services (recognising that one service can support multiple goals and each goal will depend to varying degrees on multiple services), and provide new relevant information to decision makers. In the original conception it was felt that the now identifiable risks to the ongoing health and wellbeing of the economy would be compelling to decision makers and prompt them to take early mitigating action. Of course the case of climate change would suggest there may be flaws

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

in this logic however the key difference between climate change and water resources is one of scale. Water, when understood within an environmental context, spends its terrestrial life largely within watersheds of one size or another, and these watersheds are nested within one another from the small to the very large. As such water can be a very local issue. At the subwatershed level where several towns may share the same water resource they also share many of the same social and economic interests. This comprises the common ground upon which the concept seeks to be instrumental.

However there are deeper issues with the model as presented, as I have come to understand. The valuation needed to bring ecological factors of production into decision making can be either of a monetary or non-monetary nature. The initial thesis sought to characterise economic risks primarily in economic terms using some form of monetary valuation. However while this will serve to make these factors economically visible and available to decision making, there is legitimate concern that monetisation will also expose natural assets to market forces. These concerns can sometimes be alarmist in the face of technical limitations. One example of this would be recent concerns that NAFTA could empower a sell-off of Canadian water to water scarce regions in the southwest United States. There are technical reasons, or more exactly economic constraints stemming from technical factors, which prohibit the movement of water overland on a continental scale. However the general point remains valid: monetisation of nature will expose natural assets to markets and the motivations of market actors.

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

As such we can expect institutions that manage the integration of watershed assets and natural capital in decision making to be challenged by rule-bending behaviour, itself endorsed by broader societal consensus on a capitalist system. This entails acceptance of inequality, a certain legitimisation of greed, and a setting within which the ends of accumulation to a large extent justify the means (Streeck, 2011). Where natural assets are monetised and put with reach of these forces we have to look at the nature of those assets themselves for insight into the potential risks.

Each water-based ecosystem service upon which some aspect of societys interests depends itself depends on the broader environment in numerous ways. Broadly speaking ecosystem services have been divided into four categories: regulating services, supporting services provisioning services, and cultural services (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). Provisioning, regulating and cultural services are ones which we benefit from most directly, however where all services depend on intact ecological processes, supporting services are of essential interest. This introduces another level of complexity. As compared to the benefits of many other services the direct exchange value of support services is generally indeterminate. As such any system that relies heavily on monetary approaches would tend to get the values wrong in a fundamentally important ways.

Ecosystems services do not lend themselves well to a neoclassical handling of their exchange. They depend on and are integrated into complex ecological systems where innumerable factors are working, to varying degrees, in concert with one another. It is an

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

impressive balancing act, and there are redundancies in the system, but there are also real limits that are not necessarily obvious, being obscured by the complexity of the interrelationships. There are cross-connections, non-linear feedback loops, high levels of uncertainty and real potential for irreversibility. As such the concept of a marginal unit of this ecosystem service or that natural asset has to be understood as a complete fiction. To make decisions regarding natural resources on these terms is evidently inappropriate.

There are other issues with using a neoclassical rational choice model in this case. First and foremost the idea there can be no consistency between a model that seeks to find optimal allocation at a static moment in time, and the almost infinite dynamism of a living system where metabolic processes are unfolding along a continuum of timescales. Further there are the assumptions of perfect information and rational preferences. We touched on preferences in discussing the non-market nature of fundamentally necessary supporting services, and indeed identified issues with information through discussion of the complexities of ecological processes. An additional issue where information is concerned is its availability, which also affects the apparent frictionless of transactions. Environmental monitoring is incomplete at best and access to existing data and information is hampered by a number of factors. Generally information is gathered for a specific purpose and so is tailored to that purpose. As such it may not be broadly useful, or if useful may be housed within inaccessible databases. Data is collected by a number of different agencies at all levels of government, as well as private sector and nongovernmental organisations. However there is typically no common data platform making comprehensive data sharing next to impossible. Then on the institutional side

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

there are concerns over privacy and the proprietary nature of data that can simply make data sharing a non-starter. So the information available to whatever processes and institutions are ultimately entrusted with managing the integration of natural assets into decision making will necessarily be working with imperfect information.

Drawing on Lakatoss work on the theory of knowledge Eggertson (1990) conceived a hard core for neoclassical economics consisting of stable preferences, rational choice and equilibrium structures. While changes could be tolerated in other parts of the model any substantial change to the core components suggests a new paradigm. Given the range of concerns we have with the relevance of the rational choice model and neoclassical economics to this case we have to wonder about the integrity of Eggertsons hard core, and perhaps what an improved paradigm might entail.

The totality of the discussion so far clearly indicates a need to contain and embed any neoclassical handling of natural capital assets. So far we have identified four concerns with monetisation of ecosystem services and subsequent exposure to market forces: tolerance of a capitalist system for rule bending and private accumulation; ecological importance of non-market goods; high levels of uncertainty and non-marginality; and a perforated neoclassical core. An additional dimension that needs to be considered is the common pool nature of environment as a whole, and many of its constituent services, and the consequences of private contracts that could arise from a process of monetary valuation. Holtham and Kay (1994) warn that influential special interests may use political processes to secure distributional objectives, and where the governance of

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

common pool assets is concerned they argue that broadly collective approaches are generally preferred in the provision of public services. This leads neatly into a discussion of the other side of the valuation debate and the substance of non-monetary approaches to valuation of ecosystem services.

Largely focussed on questions concerning the nature of value, for instance which ecosystem services do we value, how and why; non-monetary approaches to valuation have an implicit values-base. From the perspective of this discussion of how economics could be applied to my thesis research, the pivotal question is whose values define this values-base and how are these determined. One way to approach this question is to see the value of something as being determined by its contribution to the realisation of a userspecified goal. In the case of managing common pool assets and evaluating their role in meeting social and economic goals at a societal level, these goals and objectives will flow from the normative and moral frameworks that guide our collective beliefs and actions. As such the relationship between the act of valuation and the values upon which this activity takes place speak to the importance of social involvement in the process (Farber et al., 2002).

Evensky (1993), in an analysis of Adam Smiths Wealth of Nations, describes how individuals and society co-evolve together. Individuals inherit their values from the previous generation and in turn reshape these values going forward. For Smith this mechanism whereby individuals are shaped by and then in turn shape societys valuesbase and moral compass was what made human improvement possible. Streeck and

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

others echo this sentiment, affirming that some manner of social contract, some shared societal consensus on what is important, is needed in order to move forward, indeed for democracy to function. Rawls (1971, 2001) through his formulation of the Original Position sets out an elaborate and tightly structured theory and framework for how this could proceed through a deliberative democratic process. The essential point however is that values do matter in decision making and that these values must be those of society, meaning they must be widely shared by the citizenry. Drawing on Rawls this means they should not be defined for but rather defined by the people; they must be internal to the process. For this analysis this means non-monetary values should be determined by the process and not prior to it.

In order to meet this objective it is essential to get the institutions right, requiring the economic approach to consider the moral attributes of human agency and the temporal flow of decision and action, as suggested by Hodgson (1992). Clearly this will require a shift away from predictive theories that rely on deduction and are built on axioms and models of human behaviour, moving toward inductive analysis and interpretation of the pattern of real world phenomenon (Dugger, 1979).

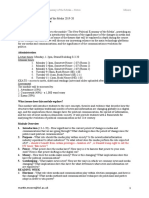

The following framework presents one approach to embedding monetary valuation within a larger institutional arrangement that draws heavily on a culturally informed statement of values and preferences, developed through deliberative democratic means, to inform and guide decision making concerning the appropriate management of natural assets relative to societal goals.

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

Communication of results Analysis of ecosystem structure and processes Definition of ecosystem services STAKEHOLDER

SMALL GROUP DELIBERATION ON PRIORITIES

Economic benefit of services Ecological thresholds Integrated analysis of costs and benefits associated with trade offs Predicted ecological response of policy options and related impacts

Socio-cultural analysis

Evaluation of ecological response and related impacts

Decision making and implementation

Ideal conceptual framework for culturally sensitised, values-based environmental decision making (Retallack & Schott, 2012)

The central stakeholder deliberative process is informed by ecological expertise to ensure that information pertinent to environmental limits and essential ecosystem services are made available for discussion. Similarly where landscapes affect culture and cultural groups can influence values positions and risk perceptions, socio-cultural analysis supplies related insight to stakeholder deliberation. Both of these expert analyses feed into other aspects of the idealised conceptual framework as illustrated. Ecological analysis and determination of key ecosystem services is shown feeding into an analysis of economic benefits. This is essentially a monetisation exercise shown here as one part of a larger decision informing and decision making structure. Depending on the weight given to different channels of information feeding into the integrated analysis of costs and

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

benefits this could effectively embed monetisation, and associated concerns regarding market forces and actors, within a larger socially-driven decision making process. One thought on how to ensure adequate weight be given to the culturally sensitised valuesbase coming out of stakeholder small group deliberative processes is to make their decision binding at some level. As such decision makers would have to either accept this guidance or overrule it, begging some manner of explanation. This communication, the feedback loop in the decision making process shown, enforces transparency and acts as an accountability mechanism and check on the action of market forces.

This framework, entirely consistent with the notion that economic transactions need a social framework within which to conduct their business, aspires to put societal values as determined by interested stakeholders at the head of decision making. Evidentially there will be challenges associated with implementation of an idealised framework within real world settings. Just what these are, how they should be managed, and how they may require the framework to be adjusted if this is even the right framework, will be central research questions going forward.

However the framework may be off to a good start. As Williamson (1994) suggests, the ideal formulation is that it be logically complete, in the sense of specifying an explicit decision making process for dealing with residual contingencies not dealt with elsewhere. Does this approach potentially signal a bureaucratisation of economic life? Possibly, however stakeholders are not all environmentalists and will have a vested interest in economic aspects extending through the ecosystem services that flow from the

10

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

environment within which they live. There will be an interest in moving things along, albeit in a measured way, balanced by addressing the contingencies.

In the case of watershed management there are certain realities that present challenges as well as opportunities. Firstly the boundaries that delineate watersheds rarely if ever align with political jurisdictions. As such numerous local level governments may have jurisdiction and mandate within a given watershed, or subwatershed. Further the perspectives and concerns of upstream stakeholders vary from those of downstream stakeholders. These factors shape many of the main challenges. We may arrive at the central opportunity presented by a watershed approach to managing water-based ecosystem services, though developing an understanding of whatever level of shared interest exists among all of these stakeholders. This will include both local economic and local environmental factors. Managing the challenges in such a way as to seize hold of this opportunity may seem like an argument for large government to coordinate all the valuation processes at various levels and arrange for compensation. Adjustments may however be more in the vein of rewiring existing institutions with the addition of a limited set of mechanisms dedicated to the purpose of facilitating development of a culturally sensitised values-base.

Whatever the final formulation, given the usefulness of cost benefit analysis when limited to specific market decisions over a short period of time, some manner of monetisation within the larger decision making structure is reasonable enough. Perhaps all the more so given the ubiquitous acceptance of this as a decision making tool. Merging with existing

11

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

systems is likely to have a higher probability of success. However it is important to heed Hahns (1982) warning concerning building policy on the foundations of neoclassical economics.

All these advocates say much more than even the pure theory allows them to say, and indefinitely more than the applicability of theory permits.

Such proposals cannot be taken seriously the story is simply too much at variance with experience.

Frank Hahn, Reflections on the invisible hand, pages 11-12.

The approach going forward will very much be that of the economic archaeologist. There exist a handful of case studies that have incorporated various aspects of a values-based approach to valuation of ecosystem services for the purposes of informing decision making. Substantial attention will be paid to really understanding success stories with a view to defining some of the basic relationships. This will be done recognising that success was possible in part due to the specificities of the particular society and economy. As the research develops more nuanced and occasionally sweeping questions will emerge. Ultimately the objective is to justify a new approach, one that views sustainable use of natural assets as a complex matter worth undertaking for a variety of compelling reasons equal in number to the number of societal and economic interests we have, in all our diversity, vested in the natural ecological systems that support us.

All over the world, were launching projects that have great potential for doing irreversible economic and political damage We cant afford the experiment of

12

PADM 6112

Economics and Institutions

April 24, 2012

developing five countries in five different ways and seeing which four countries get ruined. Instead, it will cost us much less in the long run if we hire institutional economists to find out what happened the last time.

Oliver E. Williamson, The Institutions and Governance of Economic Development and Reform, pg 194.

References Dugger, William (1979). Methodological differences between institutional and neoclassical economics, in Hausman (ed) The Philosophy of Economics (Cambridge: CUP), 336-46. Eggertsson, T. (1990). Economic Behaviour and Institutions (Cambridge: CUP), 3-32. Evensky, Jerry, (1993), Retrospectives: Ethics and the invisible hand, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(2), 197-205. Farber, S. C., Costanza, R., & Wilson, M. A. (2002). Economic and ecological concepts for valuing ecosystem services. Ecological Economics, 41(3), 375-392 Hahn, Frank (1982). Reflections on the invisible hand, Lloyds Bank Review. April, 1-21. Hodgson, G.M. (1992), The reconstruction of economics: Is there still a place for neoclassical theory?, Journal of Economic Issues, XXVI:3, 749-767. Holtham, G., and Kay, J. (1994). The assessment: institutions of policy, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 10(3), 1-16. Millennium ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and human wellbeing, wetlands and water synthesis. Washington, D.C.: World Resources Institute. Pollution Probe (2008). A New Approach to Water Management in Canada, Toronto: Pollution Probe. Rawls, John. (2001). Justice as fairness: A restatement. Ed. Erin Kelly. The Belknap Press: Cambridge. Retallack, M., Schott, S. (2012). Values Based Ecosystem Management at the Subwatershed Level, Paper presented at The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity Conference 2012, Leipzig, Germany. Streeck, Wolfgang (2011). Taking capitalism seriously: towards an institutionalist approach to contemporary political economy, Socio-Economic Review, 9(1), 137-167. Williamson, Oliver (1994). The Institutions and Governance of Economic Development and Reform, Proceedings of the World Bank Annual Conference on Development Economics (World Bank: Washington D.C.), 171-208.

13

You might also like

- Community Engagement, Solidarity, and Citizenship MODULE - QUARTER 1 - BERNADETTeDocument28 pagesCommunity Engagement, Solidarity, and Citizenship MODULE - QUARTER 1 - BERNADETTeBernadette Reyes100% (6)

- Deschooling Society Ivan IllichDocument6 pagesDeschooling Society Ivan IllichAmannNo ratings yet

- Stronger Water Utilities To Confront Commig Threats - 1aug23Document33 pagesStronger Water Utilities To Confront Commig Threats - 1aug23Eco H2ONo ratings yet

- MWM Water Discussion PaperDocument17 pagesMWM Water Discussion PaperGreen Economy CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Water Poverty IndexDocument21 pagesEnhancing Water Poverty IndexResearchteam2014No ratings yet

- Social AlternativesDocument53 pagesSocial AlternativesfungedoreNo ratings yet

- Sociology 2Document10 pagesSociology 2Mohd SaqibNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document16 pagesChapter 2Mesfin Mamo HaileNo ratings yet

- Smith 2015Document7 pagesSmith 2015Richard Solis ToledoNo ratings yet

- For Environmental Decision-Support Systems: Agent-Based ModelingDocument72 pagesFor Environmental Decision-Support Systems: Agent-Based ModelingTran SangNo ratings yet

- GWP - Social Equity and Integrated Water Resources Management - 2011Document88 pagesGWP - Social Equity and Integrated Water Resources Management - 2011nicolasbujakNo ratings yet

- PahlWostl - Integrated Water MGMNTDocument22 pagesPahlWostl - Integrated Water MGMNTjunkchanduNo ratings yet

- Addressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFDocument22 pagesAddressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFGino MontenegroNo ratings yet

- 17 Complexity Integrated Resources ManagementDocument9 pages17 Complexity Integrated Resources ManagementSarafanMalekNo ratings yet

- Water InternationalDocument10 pagesWater Internationalirina_madalina2000No ratings yet

- International Journal of Water Resources DevelopmentDocument14 pagesInternational Journal of Water Resources DevelopmentrycandraNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Social Learning in Restoring The Multifunctionality of Rivers and FloodplainsDocument14 pagesThe Importance of Social Learning in Restoring The Multifunctionality of Rivers and FloodplainsAdji KrisbandonoNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Economics and Environmental Policy DesignDocument12 pagesBehavioural Economics and Environmental Policy DesignKartik KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Natural Resource ManagementDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Natural Resource Managementogisxnbnd100% (1)

- Biodiversity at The Heart of Accounting For Natural Capital Paper July 2016 Low ResDocument13 pagesBiodiversity at The Heart of Accounting For Natural Capital Paper July 2016 Low ResewnjauNo ratings yet

- Sustainability in The Water Energy Food NexusDocument11 pagesSustainability in The Water Energy Food NexusAntoiitbNo ratings yet

- Lo RETHINKINGWATERGOVERNANCE 2017Document27 pagesLo RETHINKINGWATERGOVERNANCE 2017varshanimpi0214No ratings yet

- Smart Water Management - 2-1Document37 pagesSmart Water Management - 2-1Vishal S SonuneNo ratings yet

- The Renewable Energy Transition Realities For Canada and The World 1St Ed 2020 Edition John Erik Meyer Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Renewable Energy Transition Realities For Canada and The World 1St Ed 2020 Edition John Erik Meyer Full Chapterrobert.prevatte420100% (7)

- Kneese (1971) - Environmental Pollution, Economics and PolicyDocument15 pagesKneese (1971) - Environmental Pollution, Economics and PolicyLujan GNo ratings yet

- Water Allocation MethodsDocument43 pagesWater Allocation MethodsGabriel VeraNo ratings yet

- Water Resource Management PDFDocument47 pagesWater Resource Management PDFvandah7480No ratings yet

- The Moral Hazards of Smart Water ManagementDocument10 pagesThe Moral Hazards of Smart Water ManagementEfrizal Adil LubisNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledMohd SaqibNo ratings yet

- The Natural Capital Framework For Sustainably Efficient and Equitable Decision Making.Document8 pagesThe Natural Capital Framework For Sustainably Efficient and Equitable Decision Making.elise callerisaNo ratings yet

- Climate FinanceDocument12 pagesClimate FinanceVinícius SantiagoNo ratings yet

- 2012 Book SustainabilityScienceDocument447 pages2012 Book SustainabilityScienceSrishti PandeyNo ratings yet

- 2007 TotalWaterManagement SampleDocument18 pages2007 TotalWaterManagement SampleBogdan PopaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Management Literature Reviewc5ppm3e3100% (1)

- ECN350 Group AssignmentDocument14 pagesECN350 Group AssignmentMubashwara MehzabeenNo ratings yet

- Hamannetalchapterin ALSbookDocument40 pagesHamannetalchapterin ALSbookvardanNo ratings yet

- CirclesDocument11 pagesCirclesAnonymous UrzdtCB0INo ratings yet

- Assessing The Capacity To Govern Flood Risk in CitDocument20 pagesAssessing The Capacity To Govern Flood Risk in Citrais wrfNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 (Litrature Review) 21Document21 pagesChapter 2 (Litrature Review) 21Rushikesh PatilNo ratings yet

- System Complexity and Policy Integration ChallengesDocument14 pagesSystem Complexity and Policy Integration ChallengesJosé Eduardo ViglioNo ratings yet

- ICRE BrochureDocument10 pagesICRE BrochureBala Subramanian R RCBSNo ratings yet

- Abstract Inglés - Simposio Cambio ClimáticoDocument5 pagesAbstract Inglés - Simposio Cambio ClimáticoAgua SustentableNo ratings yet

- DDI11 SS Consumption KDocument19 pagesDDI11 SS Consumption KEvan JackNo ratings yet

- Globalization and EnvironmentalDocument24 pagesGlobalization and EnvironmentalPablo ChanNo ratings yet

- Thesis Climate Change PDFDocument9 pagesThesis Climate Change PDFzseetlnfg100% (2)

- 2014 Book GlobalizedWater-1Document303 pages2014 Book GlobalizedWater-1Daniel NaroditskyNo ratings yet

- TEEB Foundations Ecology and EconomicsDocument422 pagesTEEB Foundations Ecology and EconomicsTarcisioTeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Q3Document3 pagesQ3haikal MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Relevant Legal Frameworks Applicable To Climate ChangeDocument13 pagesRelevant Legal Frameworks Applicable To Climate ChangeanniejamesNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Document4 pagesEthics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Nethaji BKNo ratings yet

- GATsGovernanceDimensionAnalysis PDFDocument4 pagesGATsGovernanceDimensionAnalysis PDFFai RitzNo ratings yet

- The Drivers of Corporate Water Disclosure in Enhancing Information TransparencyDocument14 pagesThe Drivers of Corporate Water Disclosure in Enhancing Information TransparencyDesa PonggokNo ratings yet

- Iisa PaperDocument13 pagesIisa PaperSanatNo ratings yet

- Pedro & CastroDocument5 pagesPedro & CastrojmcastrobNo ratings yet

- Green Economy: Personal Tools NetworksDocument52 pagesGreen Economy: Personal Tools NetworksMihaela Leasă-LixandruNo ratings yet

- Red Group Module 3 AcitivityDocument8 pagesRed Group Module 3 AcitivityJet GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Concept of Sustainable DevelopmentDocument4 pagesConcept of Sustainable DevelopmentSidharth S PrakashNo ratings yet

- Flows 12Document3 pagesFlows 12jeancarlorodNo ratings yet

- Assessment Task 1 Issue SummaryDocument7 pagesAssessment Task 1 Issue SummaryManuel Pozos HernándezNo ratings yet

- Efficient Water AllocationDocument52 pagesEfficient Water AllocationEnoch ArdenNo ratings yet

- New Paradigms of Sustainability in the Contemporary EraFrom EverandNew Paradigms of Sustainability in the Contemporary EraRoopali SharmaNo ratings yet

- Environmental and Energy Policy and the Economy: Volume 2From EverandEnvironmental and Energy Policy and the Economy: Volume 2Matthew J. KotchenNo ratings yet

- Sociology (Midterm)Document8 pagesSociology (Midterm)John Aztex100% (2)

- Research and Development in Nigeria's Tertiary Institutions: Issues, Challenges and Way ForwardDocument9 pagesResearch and Development in Nigeria's Tertiary Institutions: Issues, Challenges and Way ForwardInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 5SSPP236 New Political Economy of The Media - Notes Moore: Martin - Moore@kcl - Ac.uk 1Document9 pages5SSPP236 New Political Economy of The Media - Notes Moore: Martin - Moore@kcl - Ac.uk 1Karissa ShahNo ratings yet

- Concepts and Perspective of CommunityDocument110 pagesConcepts and Perspective of CommunityJohn Leandro ReyesNo ratings yet

- Paper - Digital Economy and Development Research AgendaDocument17 pagesPaper - Digital Economy and Development Research AgendahandoutNo ratings yet

- Full Project Documentation From Group - 15 StudentsDocument104 pagesFull Project Documentation From Group - 15 StudentsGetachew Yizengaw EnyewNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Questions Part 1Document26 pagesSocial Studies Questions Part 1hyuck's sunflowerNo ratings yet

- Institutional Graduate Outcomes and Program Graduate OutcomeDocument14 pagesInstitutional Graduate Outcomes and Program Graduate OutcomeRoNnie RonNieNo ratings yet

- Concept of State and NationDocument54 pagesConcept of State and NationGaurav Tripathi100% (1)

- Logic of Consequences vs. Logic of Appropriateness Institutional DesignDocument27 pagesLogic of Consequences vs. Logic of Appropriateness Institutional Designziad_achkarRWU100% (1)

- Undp-Cb Social Cohesion Guidance - Conceptual Framing and ProgrammingDocument76 pagesUndp-Cb Social Cohesion Guidance - Conceptual Framing and ProgrammingGana EhabNo ratings yet

- 2012 PRATES R Cooperation in The Prisoners DilemmaDocument11 pages2012 PRATES R Cooperation in The Prisoners DilemmagabrielafrigolemeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 7 Vids 1 3 SS 1DDocument27 pagesChapter 1 7 Vids 1 3 SS 1DYuan Carlo ReyesNo ratings yet

- Human Rights - UN Protection of Human RightsDocument18 pagesHuman Rights - UN Protection of Human RightsKiana Porras100% (1)

- II Bauböck 2006Document129 pagesII Bauböck 2006OmarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document23 pagesChapter 3Abhijeet BhagavatulaNo ratings yet

- A2 Deviance FunctionalismDocument18 pagesA2 Deviance FunctionalismTricia TriciaNo ratings yet

- Social Science PerspectivesDocument2 pagesSocial Science PerspectiveshenokNo ratings yet

- Avelino Et Al - 2019 - Transformative Social InnovationDocument12 pagesAvelino Et Al - 2019 - Transformative Social InnovationJessica PerezNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics in Philippine PerspectiveDocument18 pagesBusiness Ethics in Philippine PerspectiveANDELYN100% (1)

- Chappell - 2010 - Comparative Gender and Institutions Directions For ResearchDocument8 pagesChappell - 2010 - Comparative Gender and Institutions Directions For Research백미록(사회과학대학 여성학과)No ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication A Current PerspectiveDocument21 pagesIntercultural Communication A Current PerspectiveJody ManggalaningwangNo ratings yet

- Issues of Strategic Implementation in Higher Educa PDFDocument28 pagesIssues of Strategic Implementation in Higher Educa PDFDanielNo ratings yet

- Edu 413Document132 pagesEdu 413Adegbosin ToluNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Urban Community Development: A Case Study From The Perspective of Self-Governance and Public ParticipationDocument15 pagesSustainable Urban Community Development: A Case Study From The Perspective of Self-Governance and Public ParticipationSAHANANo ratings yet

- Politics and Social Organization: (Group 7)Document9 pagesPolitics and Social Organization: (Group 7)Lu CelNo ratings yet

- Peacebuilding in Deeply Divided SocietiesDocument350 pagesPeacebuilding in Deeply Divided SocietiesGudeta KebedeNo ratings yet

- Sociology Exam NotesDocument38 pagesSociology Exam NotesMaria PNo ratings yet