Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Emotional Development in Gifted Children

Emotional Development in Gifted Children

Uploaded by

José CalçãoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Emotional Development in Gifted Children

Emotional Development in Gifted Children

Uploaded by

José CalçãoCopyright:

Available Formats

Ref: Freeman, J. (2008) The Emotional development of the gifted and talented, Conference proceedings.

Gifted and Talented Provision, London: Optimus Educational.

THE EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE GIFTED AND TALENTED

PROF JOAN FREEMAN

ABSTRACT

The gifted and talented are no more and no less emotionally well balanced then any other children. But they can face special emotional challenges due to stereotyping because of their differentness. These can be contradictory and confusing. Whereas some people see them as destined to suffer friendless lives others look to them as born leaders with generous social skills. Teachers and parents may pressure pupils to reach a constant high level of production in everything they do - including maturity beyond their years with little let up. The most important ways of easing of such a pressured situation for the gifted comes from being with others of the same age and similar ability, honest communication from parents and teachers, the opportunity to follow their own interests, and acceptance as individuals. --------------------------------------------Taking a lifetime view of gifts and talents shows that they may take many different forms, appear in quite unexpected situations and at different points across the years. In fact, future gifts may not even be recognisable in a child. This means that educational programmes designed for gifted pupils because of their precocity may miss those whose gifts do not fit the accepted pattern. Gifts may be outside what schools can teach, not approved of in society, or in areas not yet discovered (Freeman, 2005). But then theres a limit to what teachers can do in the classroom, and clairvoyance is usually outside their remit. As a psychologist, I have for very many years assessed the abilities of individuals. Parents sometimes say to me they are relieved if I find no evidence of giftedness in their child because they believe it can only bring stress and unhappiness. Yet the reverse is true. By far the majority of studies of the gifted and talented have found them to be emotionally stronger than others, with higher productivity, higher motivation and drive, and lower levels of anxiety (Neihart et al, 2002). Indeed, high level creativity, in particular, requires real strength of character to overcome the forces of conventionality and the sneers of those who do not understand. Probably the major emotional influence on the development of high-level potential is selfesteem. Confidence (and courage) can take a child far. For the gifted who aim for excellence at school, there is a danger that some who are insecure can take their reassurance from their school marks, rather than for themselves as rounded individuals (Freeman, 2001). One can even see the effects in adults who seem to feel obliged to provide apparently informed answers to all the concerns of the day. Such people do not appear to have a sufficiently

healthy self-esteem and that extra confidence to strike out into creative fields, no matter what anyone else may think. It is particularly difficult to find out about the normal emotional development of gifted youngsters because they so often set-off negative emotional reactions in other people which rebound on them - none of which are good for a childs emotional development. For example, people may be jealous of their abilities. Others think of the gifted as superior beings, inherently different from others, emotionally independent and without the same need for praise and love - who will consistently produce all-round excellence. Such robot-like human beings are figments of other peoples imaginations.

EMOTIONAL CHALLENGES FACING THE GIFTED AND TALENTED All long-term studies have shown the cumulative effects of family attitudes with the development of gifts (Freeman, 2000). The build up of emotional problems can start early because the gifts produce reactions in others which may be too difficult for a young child to cope with. For instance, a child may be brighter than his or her parents, who may offer too much reverence to their exceptional youngster, feeling that the normal structuring of good parenting is inappropriate for such a 'genius'. Just sometimes, abilities may develop at different and extreme rates, which can bring difficulties of developmental coordination and balance, or parents may also raise their all-round expectations, even though the child is only gifted in a specific area. The parents of gifted children can themselves have resulting emotional problems in having a gifted child, either feeling inadequate in comparison, or trying to gain social advantage from living vicariously through their child. Whatever problems already exist in the family, these can sometimes be intensified when there is a gifted (and so unusual) child present. Youngsters who have a heightened perception of what could be done can set themselves impossible expectations which can cause despair and feeling that it is not worth trying. Without adequate emotional support, even the most potentially talented child may simply give up. Gender is possibly the strongest single influence across many studies of exceptional achievement, and it has a decided emotional aspect (Freeman, 2004). Not only do many boys and girls respond differently to educational experiences, but also to their native abilities. Some gifted girls in mixed-sex schools feel that if they show their brilliance they will not be seen as feminine. They tend to be emotionally split, being more like boys in their intellectual interests, but more like other girls in their social-emotional reactions, such as too often underestimating their abilities. Mentoring and action to improve self-esteem have been found effective in promoting a more realistic presentation of abilities. What is more, while boys tend to react to failure by becoming disruptive, girls tend to react by becoming withdrawn. So the boys more vigorous responses are likely to attract more teacher and parent attention and bring about the labelling of the boys as gifted while the girls are relatively ignored. Without tests more boys are chosen as gifted than girls, usually in the proportion of 2:1.

THE FREEMAN LONGITUDINAL STUDY

The Freeman British research has taken an all-round approach to the study of gifted and talented children (Freeman, 2001). It remains unique in the world in two ways in its deep, counselling-style interviews with the subjects, their parents and teachers, across more than three decades, and in providing careful ongoing comparisons between children of different abilities. Because it is the only British longitudinal study it is the only one which can throw light on the long-term effects of being called gifted (or not) in childhood as lives continue into maturity. A major question at the start of the project was why some children were recognised as gifted, while others - of identical measured ability - were not. And then, did this label affect the identified children as they grew up. In 1974, I started with 70 children aged between five and 14, each identified as gifted by their parents. Then I matched each of these Target children with two Control children in the same school class. The First Control child was measured as identically gifted - though not labelled as such - and the Second Control child was taken at random (N=210). Each of these triads, carefully matched for age and gender, had experienced the same teaching and was from the same socio-economic population. The essential difference between the Target and First Control children was whether or not they had been labelled gifted. In my study, children were considered to be gifted who had scored at the 99th percentile on the Ravens Matrices non-verbal test of general intelligence. This was 170 children of the whole sample of 210. The childrens Stamford-Binet IQs produced a much wider range (IQ79 to IQ170) because that test measures more learned aspects of intelligence, notably words, memory, numbers and ideas. There were 13 children at the test ceiling at 170 IQ, 18 scored above 160 IQ, and 46 scored less than 120 IQ, the rest in between. Family finances ranged from terribly poor to very rich. Their 60 schools, classroom and head teachers were visited and questioned. The 210 children in the sample provided a wide variation of provision and parent and teacher outlooks. Some findings from the Freeman Longitudinal Study The following information is drawn from statistical comparisons significantly different at 1%. The idea that gifted children were bound to be 'odd', difficult and emotionally disturbed was found to be rife among parents and teachers. But was it the truth? Yes, it was true for the parents who had volunteered their children as gifted. Their children were considerably more likely than all the others to be described as friendless and difficult, and were often more troubled by problems of a nervous type, such as poor sleep, poor coordination, and asthma. The deep interviewing approach provided the information that the parents of the Target, labelled, children were themselves more likely to have emotional problems than the parents of both the Control groups. What is more, although each of the trio was in the same school-class, the parents of the labelled children had made a significantly greater number of complaints about the school, mostly because of what they saw as their children's boredom there. School provision was no different for each member of the comparison trio, and two of the trio had identical intelligence, but it was the parents of the labelled gifted children who made the most complaints about the educational provision. Interestingly, the children themselves did not complain of boredom. The next statistical move was to take the children out of their original groups and compare all the information I had about them in respect of their IQ scores. No significant relationship could be found between IQ alone and any behavioural problems, nor with personality, other

than a 5% tendency to extraversion in the music performers. Children with IQs over 140 were neither found to sleep less nor more fitfully - parents had been questioned very carefully on this often-described feature of the gifted. Rather, at all levels of ability, the time a child spent in sleep was found to be directly related to both age and emotional problems. Younger children slept more, and emotionally disturbed children slept less. The gifted had as many friends at school as other children, but fewer at home due to the nature of their out-of-school activities, such as music practice, hobbies, and more homework. There were no differences in the childrens physique or pattern of health across the whole sample. As with all children, physical co-ordination was found to be related to psychological adjustment, and boys had more difficulty than girls with fine motor control, which was most likely to show up in their poor handwriting. Well behaved children who simply did well at their lessons, and who had fewer emotional problems, notably girls, were far less likely to be given the label of 'gifted'. This meant that the Target, labelled, parents-chosen group had two boys to every girl. Where any of the children had emotional problems they were almost entirely due to causes that would distress any child, such as bad parental relationships, divorce, frequent house moves, or other disturbances. The unhappiness brought the symptoms, such as sleep problems, bed-wetting, asthma etc, for which drugs were sometimes prescribed. In some cases, the distress in the whole family even seemed to have been focused on the labelled gifted child and not on the other children. Across the range of intelligence in the sample of 210 children, the best adjusted children had the most friends. As theyve grown older and they are now in their forties - age has smoothed most, though not all, of their childhood problems. They have moved out of their parental homes (from which many of their problems seemed to come), made their own lives and found ways of life and companions to suit themselves. They are afflicted with the same problems as other people, such as overwork, depression and a feeling of could have done better with their lives. Those who have children tell me now that they can see how their own emotional problems arose and they are determined not to inflict these on the next generation. Some grieve for their lost childhood time to play and experiment. So much of their young lives was spent in heavy study. It was expected that they would produce the goods the excellent examination results and prestigious university entry which their gifts supposedly entitled them to. At school In their teen years, most of the gifted said they felt their teachers estimated their scholastic abilities correctly. Asked what they wanted from their teachers, many spoke of a mixture of firmness and real concern for them as individuals. But too strict a discipline was seen as actually detracting from a subject. Those who were under-achieving were mostly aware of the reasons for it, and told me quite specifically, in particular about family problems, their preference for fun rather then work, and at times their poor self-concepts. No gifted underachiever that I spoke to was ever satisfied with the situation. A handful of the gifted teenagers seemed to be squeezed to the last drop of effort to do better and better by parents and teachers, and consequently, their self-esteem sometimes depended entirely on their academic rewards. Some of the gifted described themselves as 'lazy' (although their parents said they worked very hard), feeling that the work was too easy to

justify their high marks. Most unfortunately, pressure to excel was also imposed by parents on some children who were seen as gifted - but who were not - which brought about a remarkable variety of excuses for their under-achievement', as well as some depression in a few of the children. BEING DIFFERENT FROM OTHERS No matter how gifted they are, those who try to live up to any of the myths about giftedness are almost always doomed to failure. Under pressure, some of the teenage gifted aimed for perfection which could be seen as arrogance. Parents themselves could have emotional problems because they found their child to be gifted. They could feel inadequate in their ability to bring their child up, or may try to gain social advantage from their child. Whatever problems there were already in the family, such as marital strife, they could be intensified when there was a gifted child present. Many parents who want the best for their dearly loved children are almost apologetic when they bring them to me for assessment, almost as though they felt they shouldnt know. Normally the parents instincts are right they do have a gifted child but some times they are wrong. Although boredom can sometimes be a problem for advanced youngsters with curious minds in a normal classroom, this is most likely to be a personal reaction unrelated to gifts and talents: in the same situation one individual will be bored and another will find challenge. Many average ability children are bored in school and indeed throughout their lives. Boredom can become a habit, so that a child learns to expect it and interprets too many experiences that way. Its a sort of Am I bovvered coolness which afflicts teenagers, perhaps a fear of appearing to care and thus becoming emotionally vulnerable. The gifted, like any others, need the enjoyable stimulation of variety, and the excitement that can come from playing with ideas. So, when lessons are too easy, they lose the satisfaction of tackling and resolving problems. To compensate, some (usually boys) may deliberately provoke disturbance - just for the spice of stimulation. Others, though, hide behind academic, intellectual walls of their own making, implying that they are too clever to have normal relationships with ordinary people. The emotional effects of some often-used educational provision for the gifted are considered here: Separate education Any form of separate education for the gifted over the whole of their school lives may complicate relationship problems, such as growing up without the facility to mix easily with others of the sae age, of more average ability and different education. There are some kinds of gifts or talents, though, which do seem to call for full-time specialist education - notably music and the performing arts. It is true that when highly able children are grouped together for teaching, they make better progress in their school work. Some of the people in my sample said that the slow pace of normal class-room learning was irritating and held them back. Acceleration There is some disagreement about putting children in classes above their age-group by a year or more. Any of the growing-up problems in my sample increased for all but one of the 17 youngsters who were accelerated. Having to make relationships every day with class-mates

who were emotionally more mature was confusing, and it also aggravated delicate relationships at home. Nor did it even seem to benefit most of the young people's school and life success: some had done less well than had been expected at school from their earlier achievements. Though there may be situations in which it seems to be the only way out, any child who is accelerated will need extra emotional support. If a group, such as a whole class, is accelerated, it can be much easier. Unless a pupil is not only highly gifted, but mature for his or her years, school acceleration does not seem to be the best option. Part-time withdrawal Experience shows that it all depends how part-time pull-out classes are conducted. For example, if the gifted are taken somewhere exciting for a geography field trip, it is reasonable for the rest of the desk-bound class to feel envy - not least because they too would probably benefit from the trip. But withdrawing the gifted for specialist tuition in mathematics or a foreign language is less likely to be envied. Unfortunately, though, withdrawals of the intellectually gifted are often likely to be made during unimportant lessons like physical education, which they need as much as any other child. Enhanced academic achievements in the gifted have been reported from such pull-out classes in America, as well as improved self-confidence and more positive attitudes towards school and school-work. Handled sensitively, it does not seem to upset the others in the class. Holiday courses Special courses have not been found to be effective in the long term, though they are very enjoyable at the time (Freeman, 2002). American experience over half a century and so many thousands of children has still not produced a world leader who can be said to owe this to holiday courses. The National Academy for Gifted and Talented Youth for older children in England, set up by the government, closed after only five years because it did not seem to justify the extreme expense. The government is now spreading its largesse more widely, including four year-olds. SPECIFIC EMOTIONAL HELP FOR THE VERY ABLE The real differences between the gifted and the others lie in their abilities, not in their emotional lives. However, they may need some extra emotional help in the form of adult awareness and support. The gifted need honest communication, the opportunity to follow their interests, stimulation of like-minds, and acceptance as all-round people rather then learning machines. An environment in which the exceptionally able child can prosper all round must be balanced - allowing enough time with other people to make good social relationships, developing interests outside school study areas, and taking part in nonacademic school and community activities. This calls for recognition and the efforts of parents and teachers to make sure that the non-examinable side of pupils' lives is adequately promoted. Proposals for the emotional well-being of the gifted and talented Counselling techniques for the gifted are similar to those for all children, including good counsellor-parent communication. But additionally counsellors must be aware of the possible stresses and needs of the gifted, which may for example, come from acceleration. Vocational guidance cannot begin too early.

Out-of-school activities can be coordinated for gifted and talented pupils with schools in the area, such as weekend activities, competitions, or summer camps, where they can meet and relax with others like themselves. Mentoring means that a carefully selected adult with particular expertise takes a special interest in a highly able youngster. An older child may, for example, work alongside a scientist in a laboratory doing original research. This usually has additional positive emotional effects. Facilities should be provided for enrichment in education, including extra courses, specialist advisors, and events for gifted pupils. If the level is high, pupils can be selfselecting, avoiding the hazards of selection by test identification Freemans Sports Approach. A school atmosphere in which attention and provision for the highly able is a normal and natural aspect of differentiated education for all pupils promotes healthy emotional development. It is important for teachers and parents to avoid the temptation to put too much emphasis on the development of scholastic achievements. Gifted youngsters respond well to teachers who will work with them, rather than for them, to teachers who are concerned with the structure of their learning as much as the content not least with the pupil's social development. Teachers of the gifted and talented need both pre-graduation and in-service courses to help them teach in this special area of education. This would include concern with learning styles and skills. Teachers should be provided with a bank of curriculum enrichment materials and teacher-education materials in a resource centre, open outside school-hours. It is important to recognise that to be creative includes permission to question and play with knowledge. Rigid teaching styles work against creativity. If in doubt ask the pupils what they would like. Conclusion

The final conclusion is positive - that the gifted who are appreciated and accepted for who they are in their homes and schools with recognition of their abilities and needs will be as well balanced and as least as able as any others to adapt to and contribute to society.

REFERENCES Freeman, J. (1998) Educating the Very Able: Current International Research. London: The Stationery Office. Freeman, J. (2000) Families, the essential context for gifts and talents, in K.A. Heller, F.J. Monks, R. Sternberg & R. Subotnik, International Handbook of Research and Development of Giftedness and Talent. Oxford: Pergamon Press, (669-683). Freeman, J. (2001) Gifted Children Grown Up. London: David Fulton Publications; Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis. Freeman, J. (2002) 'Out of School Educational Provision for the Gifted and Talented around the World', Report for the UK Government Department for Education and Skills. Freeman, J. (2004), Cultural influences on gifted gender achievement, High Ability Studies, 15, 7-24. Freeman, J. (2005) Permission to be gifted: how conceptions of giftedness can change lives, in R. Sternberg & J. Davidson, Conceptions of Giftedness, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Neihart, M., Reis, S.M., Robinson, N.M. & Moon, S.M. (2002) Social and emotional issues facing gifted and talented students: What have we learned and what should we do now?, in Neihart, M., Reis, S.M., Robinson, N.M. & Moon, S.M., The Social and Emotional Development of Gifted Children. What Do We Know? Washington: Prufrock Press.

Most of the references to non-book publications by Joan Freeman are available to download free from www.joanfreeman.com

You might also like

- Template Diary Special Needs AssistingDocument2 pagesTemplate Diary Special Needs Assistinglouise mc donnellNo ratings yet

- Ap Psych Final Project MatildaDocument20 pagesAp Psych Final Project Matildaapi-409170054No ratings yet

- 5057 Maxwell Chapter 5Document26 pages5057 Maxwell Chapter 5Soban JahanzaibNo ratings yet

- Elements of Reservation - LPDocument9 pagesElements of Reservation - LPJulie Anne PeridoNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological Research GuidelinesDocument4 pagesPhenomenological Research GuidelinesOxymoronic Blasphemy89% (9)

- Anti Bullying Act of 2013Document30 pagesAnti Bullying Act of 2013marjoerine100% (2)

- Self Measures For Self-Esteem STATE SELF-ESTEEMDocument4 pagesSelf Measures For Self-Esteem STATE SELF-ESTEEMAlina100% (1)

- Dos ChecklistDocument2 pagesDos ChecklistIlsse Nava100% (1)

- Twice ExceptionalDocument46 pagesTwice Exceptionalapi-360371119No ratings yet

- Inclusion and Placement Decisions For Students With Special NeedsDocument11 pagesInclusion and Placement Decisions For Students With Special NeedsDaYs DaysNo ratings yet

- Issues in The Social and Emotional Adjustment of Gifted ChildrenDocument12 pagesIssues in The Social and Emotional Adjustment of Gifted Childrenapi-301904910No ratings yet

- Empowering Parents & Teachers: How Parents and Teachers Can Develop Collaborative PartnershipsFrom EverandEmpowering Parents & Teachers: How Parents and Teachers Can Develop Collaborative PartnershipsNo ratings yet

- Profoundly Gifted PresentationDocument7 pagesProfoundly Gifted Presentationapi-317335384No ratings yet

- Instrumental Enrichment and Metacognition': How To Teach IntelligenceDocument13 pagesInstrumental Enrichment and Metacognition': How To Teach IntelligenceAlexandra DumitracheNo ratings yet

- Fba ChecklistDocument3 pagesFba Checklistapi-453271503No ratings yet

- DYSCALCULIA RESEARCH TITLE 1 .Docx GatduDocument15 pagesDYSCALCULIA RESEARCH TITLE 1 .Docx GatduLuthyGay VillamorNo ratings yet

- Improving Theory of Mind FinalDocument15 pagesImproving Theory of Mind FinalAnnick ComblainNo ratings yet

- S Woodson Bright Vs Gifted Vs Creative Blank Chart-July 16Document6 pagesS Woodson Bright Vs Gifted Vs Creative Blank Chart-July 16api-293411786No ratings yet

- Social and Emotional (SEL) Parent Survey LetterDocument2 pagesSocial and Emotional (SEL) Parent Survey LetterDana LitNo ratings yet

- Bandura and Maslow HandoutDocument5 pagesBandura and Maslow Handoutapi-296978454No ratings yet

- A Culturally-Inclusive Classroom EnvironmentDocument3 pagesA Culturally-Inclusive Classroom EnvironmentAlexana Bi VieNo ratings yet

- Cognitive DisabilitiesDocument4 pagesCognitive Disabilitieshannalee13No ratings yet

- Classroom Managment PlanDocument10 pagesClassroom Managment PlanTara100% (1)

- 2018 Growth-Mindset-Strategies Website PDFDocument4 pages2018 Growth-Mindset-Strategies Website PDFMohini SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Article 1Document11 pagesArticle 1api-277266097No ratings yet

- Exceptional LearnersDocument16 pagesExceptional LearnersBlack ScreenNo ratings yet

- Therapy: Haiza Nur Sabrina Zulaikha Nurul Aini Ummi Norkhairiah Pinky TangDocument18 pagesTherapy: Haiza Nur Sabrina Zulaikha Nurul Aini Ummi Norkhairiah Pinky TangHaiza Ieja IINo ratings yet

- Examining Student Behavior: Determining Intervention Through Deeper UnderstandingDocument17 pagesExamining Student Behavior: Determining Intervention Through Deeper Understandinggryphon688No ratings yet

- Dyspraxia LeafletDocument6 pagesDyspraxia LeafletMelissa Martinez100% (1)

- The Seven R's Are Relationships, Rules, Routines, Rights, Responsibilities, Respect and RewardsDocument19 pagesThe Seven R's Are Relationships, Rules, Routines, Rights, Responsibilities, Respect and RewardsJonny xiluNo ratings yet

- Twice Exceptional HandoutDocument2 pagesTwice Exceptional Handoutapi-301904910No ratings yet

- The Cognitive TheoryDocument2 pagesThe Cognitive TheoryAndres CruzNo ratings yet

- Floortime in Schools and Home. Formal Floortime and Floortime Philosophy in All InteractionsDocument7 pagesFloortime in Schools and Home. Formal Floortime and Floortime Philosophy in All InteractionsLeonardo VidalNo ratings yet

- Psychological Aspects of Gifted ChildrenDocument5 pagesPsychological Aspects of Gifted Childrenlazarstosic100% (1)

- Observation ChecklistDocument2 pagesObservation Checklistapi-293994881No ratings yet

- AdolescenceDocument19 pagesAdolescencerahtu suzi ameliaNo ratings yet

- Fvlma Ecc Assessment PDFDocument14 pagesFvlma Ecc Assessment PDFapi-264880707No ratings yet

- Emotional Development in Children With Developmental Disabilities PDFDocument27 pagesEmotional Development in Children With Developmental Disabilities PDFL100% (1)

- Cooperative LearningDocument5 pagesCooperative LearningJan Aries ManiponNo ratings yet

- ADHDDocument17 pagesADHDapi-3822433No ratings yet

- Preschool Parent Handbook 09-10Document20 pagesPreschool Parent Handbook 09-10Mawan ManyokNo ratings yet

- sp0009 - Functional Assessment PDFDocument4 pagessp0009 - Functional Assessment PDFMarlon ParohinogNo ratings yet

- 03.HG Theories of Child BehaviorDocument9 pages03.HG Theories of Child BehaviorEthel KanadaNo ratings yet

- Tier II Behavior Intervention Descriptions2Document13 pagesTier II Behavior Intervention Descriptions2api-233605048No ratings yet

- Parent As Role Model Info.Document6 pagesParent As Role Model Info.Raven Zarif AzmanNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Reducing Disruptive Behavior: A Behavioral Intervention PlanDocument32 pagesRunning Head: Reducing Disruptive Behavior: A Behavioral Intervention Planapi-270220817No ratings yet

- CC SR ProjectDocument11 pagesCC SR Projectapi-617045311100% (1)

- Metacognitive Rubrics For Assessing Student Learning OutcomesDocument4 pagesMetacognitive Rubrics For Assessing Student Learning OutcomesSafaruddin Al Afgani0% (1)

- Direct InstructionDocument4 pagesDirect Instructionapi-336148477No ratings yet

- Pedagogy For Positive Learning Environments Assessment 1 ReportDocument10 pagesPedagogy For Positive Learning Environments Assessment 1 Reportapi-407779935No ratings yet

- Behavior Basics Volume 1 MARADDocument67 pagesBehavior Basics Volume 1 MARADnexhixijeNo ratings yet

- Functional Assessment Checklist For Prog PDFDocument76 pagesFunctional Assessment Checklist For Prog PDFRishi SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Behavior Problems in The ClassroomDocument17 pagesBehavior Problems in The ClassroomAPRILYN REFENDOR BCAEd - 4DNo ratings yet

- Direct Instruction Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesDirect Instruction Lesson PlanjacquiserraNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Assumptions: Personality Psychology Is A Branch ofDocument45 pagesPhilosophical Assumptions: Personality Psychology Is A Branch ofpkatareNo ratings yet

- Identifying Your Child's Personality Type: Highly Sensitive, Self-Absorbed, or DefiantDocument12 pagesIdentifying Your Child's Personality Type: Highly Sensitive, Self-Absorbed, or DefiantpakcipanNo ratings yet

- Gifted NotesDocument8 pagesGifted Notesapi-288159071No ratings yet

- 4 Strategies of AfLDocument13 pages4 Strategies of AfLSadiaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CurriculumDocument59 pagesIntroduction To CurriculumCrizalyn May Austero Salazar100% (1)

- Dads and AutismDocument50 pagesDads and AutismcirclestretchNo ratings yet

- Parenting Inspired: Follow the Path, Where the Child Loves to GrowFrom EverandParenting Inspired: Follow the Path, Where the Child Loves to GrowNo ratings yet

- Raising Bright Sparks- Book 1. Parenting Gifted ChildrenFrom EverandRaising Bright Sparks- Book 1. Parenting Gifted ChildrenNo ratings yet

- The Implication of Teaching Strategies On The Academic Performance Among Grade 10 STE StudentsDocument5 pagesThe Implication of Teaching Strategies On The Academic Performance Among Grade 10 STE StudentsKristoffer AgalaNo ratings yet

- Career Ready StudentsDocument6 pagesCareer Ready StudentsIulia PetrescuNo ratings yet

- Timothy K JonesDocument2 pagesTimothy K JonesTheLivingChurchdocsNo ratings yet

- Ucchatar Madhyamik Star Par Adhyayanrat Shahari Aur Gramin Vidhyarthiyon Ke Adhyatmik Mulyon Ka Tulnatmak AdhyayanDocument10 pagesUcchatar Madhyamik Star Par Adhyayanrat Shahari Aur Gramin Vidhyarthiyon Ke Adhyatmik Mulyon Ka Tulnatmak AdhyayanAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Assessment and FeedbacksDocument5 pagesAssessment and FeedbacksCekgu InggerihNo ratings yet

- Format of The Thesis - Project ReportDocument4 pagesFormat of The Thesis - Project ReportAugust mishraNo ratings yet

- Perception About Gender Equality of Senior High School Students in General de Jesus College S.Y. 2019 - 2020Document48 pagesPerception About Gender Equality of Senior High School Students in General de Jesus College S.Y. 2019 - 2020Kaira Jeen PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Laone ReportDocument22 pagesLaone ReportLaone DiauNo ratings yet

- MENSDocument18 pagesMENSVel MuruganNo ratings yet

- GMAT Quantitative Diagnostic TestDocument8 pagesGMAT Quantitative Diagnostic TestLuis MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- DLL Grade3 Q1 WK 8Document14 pagesDLL Grade3 Q1 WK 8April ToledanoNo ratings yet

- Anna Berg: Experience SkillsDocument3 pagesAnna Berg: Experience Skillsapi-543413393No ratings yet

- 9 Box + Chart TemplateDocument2 pages9 Box + Chart TemplateIqrä QurëshìNo ratings yet

- Kinder-New-DLL Week12 - Day1Document5 pagesKinder-New-DLL Week12 - Day1NOVELYNENo ratings yet

- Dyslexia: Dyslexia Is A Type of Aphasia Where Damage To TheDocument36 pagesDyslexia: Dyslexia Is A Type of Aphasia Where Damage To Theshivam singhNo ratings yet

- Mark Scheme Synthesis and Analytical TechniquesDocument33 pagesMark Scheme Synthesis and Analytical TechniquesAddan AddanNo ratings yet

- L&D Strategy: Design The Next Generation of Corporate AcademiesDocument6 pagesL&D Strategy: Design The Next Generation of Corporate Academiesnick100% (2)

- Vocational Training ProgramDocument6 pagesVocational Training ProgramolabodeogunNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics 3Document5 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics 3Gerald DeganoNo ratings yet

- MultiDocument3 pagesMultiapi-272938699No ratings yet

- Jilan Akbar-ResumeDocument1 pageJilan Akbar-ResumeJilan akbarNo ratings yet

- Pune Database of Educational GroupsDocument74 pagesPune Database of Educational GroupsShreyas AashishNo ratings yet

- 2020 NAAB Conditions For AccreditationDocument15 pages2020 NAAB Conditions For AccreditationSally AlaslamiNo ratings yet

- Learning Assessment StrategiesDocument5 pagesLearning Assessment StrategiesMarjory De Leon AlbertoNo ratings yet

- D Epartment of Education: R Epublic of The P HilippinesDocument3 pagesD Epartment of Education: R Epublic of The P HilippinesNIMFA PADILLANo ratings yet

- 1516S1 CCN2014 Food Hygiene Individual AssignmentDocument7 pages1516S1 CCN2014 Food Hygiene Individual AssignmentPoon Wai Shing AesonNo ratings yet

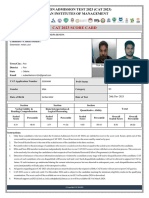

- Cat 2023 Score Card: Common Admission Test 2023 (Cat 2023) Indian Institutes of ManagementDocument1 pageCat 2023 Score Card: Common Admission Test 2023 (Cat 2023) Indian Institutes of Managementsubashbehera1224No ratings yet