Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ironic 56 Eating 2002

Ironic 56 Eating 2002

Uploaded by

Mandy WangOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ironic 56 Eating 2002

Ironic 56 Eating 2002

Uploaded by

Mandy WangCopyright:

Available Formats

1

British Journal of Health Psychology (2002), 7, 110 2002 The British Psychological Society www.bps.org.uk

Ironic processes in the eating behaviour of restrained eaters

Brigitte Boon1*, Wolfgang Stroebe2, Henk Schut2 and Richta IJntema2

1 2

Maastricht University, The Netherlands Utrecht University, The Netherlands

Theory. The present study examines the processes underlying the disinhibition of the eating behaviour of restrained eaters following negative emotions. Based on Herman and Polivys (1984) Boundary Model and Wegners Ironic Process Theory (1994), the limited capacity hypothesis is formulated, suggesting that overeating in restrained eaters results from cognitive capacity limitations. Predictions were that (1) impairment of cognitive capacity during eating will lead to overeating in restrained but not in unrestrained eaters and that (2) this difference should only emerge with food perceived to be high in calories. Method. The hypotheses were tested in an experiment with a 2 (restrained/ unrestrained) 3 2 (distraction yes/no) 3 2 (perceived calories high/low) design, in which subjects consumed ice-cream in a taste test situation. Ice-cream consumption was the dependent variable. Results. A second-order interaction was found: as predicted, in the high calorie condition restrained eaters ate the same amount as unrestrained eaters when not distracted, but considerably more when distracted. There was also an unexpected main effect of distraction, which indicated that restrained as well as unrestrained eaters ate more if distracted than if not distracted. Discussion. The restraint 3 distraction 3 perceived calories interaction can be explained by both the Ironic Process Theory and the Boundary Model; and the limited capacity hypothesis appears to be con rmed. The overall main effect of distraction remains puzzling. Two speculative views for the latter effect are offered.

There is a great deal of evidence to suggest that overeating is frequently an unintended consequence of dieting (see e.g. Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Lowe, 1993; Ruderman, 1986). The notion that dieting, and not body weight, plays a key role in the regulation of food intake stimulated the theoretical development of the construct of

*Requests for reprints should be addressed to Dr Brigitte Boon, Maastricht University, Faculty of Psychology, Department of Experimental Psychology, PO Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands (e-mail: B.Boon@psychology.unimaas.nl).

Brigitte Boon et al.

dietary restraint in the mid-1970s (Herman & Mack, 1975). The construct refers to the cognitively mediated effort to curb the urge to eat, and can be assessed by the Restraint Scale (Polivy, Herman, & Warsh, 1978). An intriguing explanation for overeating in restrained eaters is given by Herman and Polivys Boundary Model (1984). According to this model, biological pressures work to maintain consumption within a certain range in all individuals. The consumption above some minimum level is assured by the aversive quality of hunger, and consumption below a maximum level by the aversive quality of satiety. The area between these two boundaries is called the range of biological indifference and it is within this range that psychological factors are thought to be most in uential. Herman and Polivy state that there are two differences between restrained and unrestrained eaters. First, the range of biological indifference is assumed to be wider in restrained than in unrestrained eaters. Due to repeated dieting and overeating in the past, restrained eaters are expected to have lower hunger and higher satiety boundaries. Second, it is postulated that restrained eaters have a third, self-imposed boundary, the diet boundary, a cognitive limit that marks their maximum desired consumption. Central to the boundary model is the prediction that transgression of the diet boundary induces overeating. This so-called preload effect has been investigated in numerous studies (see e.g. Boon, 1998; Ruderman, 1986, for reviews). More important in the light of the present study is a second prediction suggested by Herman and Polivy (1975, 1984) concerning the empirically well demonstrated disinhibitive effect of negative emotions on the eating behaviour of restrained eaters. Laboratory as well as naturalistic research has demonstrated that negative emotional states such as anxiety (e.g. Herman & Polivy, 1975; Polivy, Herman & McFarlane, 1994) and depressed mood (e.g. Baucom & Aiken, 1981; Cooper & Bowskill, 1986; Frost, Goolkasian, Ely & Blanchard, 1982; Ruderman, 1985; Schotte, Cools & McNally, 1990) induce overeating in restrained eaters but not in unrestrained eaters. Herman and Polivy have argued that the effect of negative emotions is best interpreted as the imposition of a more urgent concern (i.e. how to cope with the stressor) than even dieting and they add that in the case of negative emotions eating may proceed as if the diet boundary had been transgressed (Herman & Polivy, 1984, p. 152). In the present study, it is suggested that coping with negative emotions requires attention and since cognitive capacity is not unlimited, exerting control over their eating behaviour may be affected by this. Restraining food intake may be assumed to require a great deal of the available cognitive resources. Restrained eaters need to be aware, for example, of the caloric value of food and should constantly monitor what and how much they eat and compare this amount to their maximum desired consumption. It is easy to see that having to cope with a negative emotion may interfere with a persons goal of controlling eating behaviour. An interesting question in the light of this explanation of the disinhibitive effect of negative emotions, is whether this effect is speci c for negative emotions or whether it is merely the general effect of a limited cognitive capacitydue to any factorthat compromises restrained eaters diets. This might partly explain the fact that so many dieters end up gaining, instead of losing, weight (Klesges, Isbell & Klesges, 1992). The empirical evidence so far, however, does not allow conclusions regarding the limited capacity hypothesis because so far no study has directly tested this hypothesis. However, indirect support can be derived from a study of Cools, Schotte, and McNally (1992), who examined the effect of mood on eating behaviour. The authors induced negative, positive and neutral moods by having subjects watch frightening, comedy and

Ironic processes in eating behaviour

neutral lms, respectively, during which they could eat popcorn. Restrained eaters in both the negative and positive mood conditions ate more than those in the neutral condition; the unrestrained eaters were unaffected by the emotion induction. Until now this effect of positive emotions has remained puzzling. The limited capacity hypothesis may clear up the picture. It may be assumed that positive emotions, like negative emotions, require attention and thus limit the amount of cognitive capacity still available for controlling food intake. Some further preliminary support for the limited capacity hypothesis can be found in an interesting series of studies by Green and colleagues. They found that current dieters1 displayed a signi cantly lower working memory span than non-dieters and this effect was related to participants self-rated desire to eat (e.g. Green, Elliman & Rogers, 1997). However, this nding does not allow conclusions regarding the effect of a limitation of subjects cognitive capacity on actual food intake, since consumption was not included as a dependent measure. Theoretically, the limited capacity hypothesis is supported by Wegners Ironic Process Theory (Wegner, 1994). This theory considers the relevance of cognitive capacity for maintaining mental control and the danger of losing it in times of capacity limitation. Wegner suggests processes that may explain the occurrence of the opposite of what a person intends to achieve (e.g. overeating in restrained eaters) as a consequence of this limited capacity. He postulates two processes that are responsible for mental control: the intentional operating process and the ironic monitoring process. The intentional operating process searches for items that are consistent with a desired state of mind and creates this state by occupying the mind with thoughts and sensations relevant to it. The operating process thus re ects a controlled process: it is effortful, consciously guided and demands cognitive capacity. The monitor, on the other hand, searches continuously for items that are inconsistent with the desired state and indicates failure of mental control. This way, the monitor regulates whether or not the operating process will be initiated. The monitoring process is unconscious and requires little cognitive effort. The main hypothesis derived from Ironic Process Theory is that under mental load, intentions to control the mind unleash a monitoring system that not only searches for the failure of mental control but tends itself to create that failure (p. 34). An elegant series of studies by Wegner and his co-workers established that limitations of an individuals cognitive capacity result in a mental state which is the opposite to the desired state, the so-called ironic process (Wegner & Erber, 1993; Wegner, Erber & Zanakos, 1993; Wegner, Schneider, Carter & White, 1987). For example, participants who were instructed not to think about a target word frequently responded with this target word when asked to respond to target-relevant prompts under time pressure. They mentioned the word that they were told not to think about more often than participants who performed the task without being under time pressure. Wegner suggests that behavioural control may follow many of the same ironic pathways traced by mental control (1994, p. 34). This suggestion is not (yet) empirically supported. Regarding eating restraint, the Ironic Process Theory would

Following Lowe (1993), they divided restrained eaters into those who were currently on a diet and those who were not on a diet. Lowe showed that these two types of restrained eaters display different eating regulation patterns. In the present study, this distinction was not made since we expected that both types of restrained eaters would direct cognitive resources at restraining food intake. It may be hypothesized that current dieters will do so more extremely, but this was not examined in the present study.

Brigitte Boon et al.

suggest that the operating process of restrained eaters aims at restricting food intake, whereas the monitor searches for signs inconsistent with food restriction. The operating process (I should not eat that food), then, should be susceptible to cognitive distraction, i.e. a limitation of the cognitive capacity due to a cognitive load, whereas the monitor (I want to eat that food) should not. The monitor may thus go on searching for failure of the dietary restraint, whereas the operator may not be initiated. In this situation, it will be very dif cult for the restrained eaters to refrain from eating. The limited capacity hypothesis can thus be derived from the Ironic Process Theory: cognitive distraction should lead to the ironic effect of overeating in restrained eaters, whereas it should not affect the food intake of unrestrained eaters (see also Boon, 1998). To test this hypothesis, a study is needed in which cognitive capacity is manipulated directly rather than indirectly via strong emotions. The present article reports an experiment in which restrained, as well as unrestrained, eaters were either cognitively distracted or not distracted while performing a taste test. Furthermore, as suggested in a previous study (Boon, Stroebe, Schut & Jansen, 1997), the strength of the intention of restrained eaters to control their eating was manipulated by varying the perceived caloric value of the ice-cream in this taste test. The degree of danger restrained eaters attach to certain food is likely to in uence the strength of their intention to avoid it. In the light of Wegners (1994) theory, it can be assumed that restrained eaters monitors are especially alert if high caloric food is concerned; the more calories, the higher the risk of dietary failure. To investigate these notions, perceived calorie content as well as distraction were manipulated in a 2 (perceived calories high/low) 3 2 (distraction yes/no) 3 2 (restrained/ unrestrained eaters) design. Restrained and unrestrained individuals were asked to taste ice-cream under distraction or no-distraction conditions. For half the participants, the ice-cream was described as particularly low in calories, for the other half as particularly high (the ice-cream was actually the same for both groups). The dependent measure consisted of the amount of ice-cream eaten. A restraint by distraction interaction was predicted for the high, but not the low, calorie condition; thus in the high calorie condition, restrained eaters were expected to eat more than unrestrained eaters when distracted, but to eat the same or even less than unrestrained eaters when not distracted. With low calorie ice-cream, distraction should not affect the eating control of restrained eaters. For the unrestrained eaters, who are assumed not to regulate their eating behaviour cognitively, neither the distraction, nor the calorie manipulations should have any effects on their eating behaviour.

Method

Participants

A group of 126 female students from different departments at Utrecht University volunteered to participate in the experiment. All participants had eaten their usual meal; there were no indications that groups differed in level of deprivation. Three students guessed the purpose of the experiment, and one claimed to dislike ice-cream; these four were excluded from further analyses. Participants mean score on the Restraint Scale (RS, see below for description) was 11.2 (SD 4.9, range 0-23), with a median score of 11.2 Participants were classi ed as restrained or

2

The median score for RS was lower in our study than is usual in American research; however this pattern is typical for research conducted in the Netherlands (e.g. Jansen, Oosterlaan, Merckelbach & van den Hout, 1988).

Ironic processes in eating behaviour

unrestrained eaters by means of a median split of the RS scores. Seven participants scored exactly the median, and were not included in either group. A total N of 115 resulted. Table 1 shows the mean age, body mass index (BMI) and RS scores for the restrained and unrestrained eaters.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants Restrained (N 5 56) N5 115 M 21.1 15.4 23.3 (SD) (2.4) (3.0) (2.5) Unrestrained (N 5 59) M 21.2 7.3 20.6 (SD) (2.3) (2.4) (1.8) t 0.1

2 16.0 2 6.6

p NS .00 .00

Age RS score BMI

Independent variables Perceived calorie content

The perceived calorie content of the ice-cream was manipulated by telling half the participants that the ice cream is extra creamy, whereas the other half were told The ice cream is from a rm that specializes in light products. They have managed to produce ice cream that tastes as creamy as other ice-cream, but contains 30% fewer calories. The effect of the calorie manipulation was assessed with the following question: How many calories did this ice-cream contain, compared with normal ice-cream?. The answer was given on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 50% less to 50% more calories.

Distraction

Distraction was manipulated by introducing a task that had already been pretested and used in a previous experiment (Boon et al., 1997). It consisted of listening to a 15-minute radio conversation. Participants were rst instructed on how to perform the taste test (see procedure). Half were then told that in the meantime they would have to listen to the radio conversation. The instruction was to pay full attention to the conversation and to count the number of animal words guring in the conversation. Participants were told that they had to answer questions about the content of the conversation afterwards. Two subjective measures of distraction were included as a manipulation check. Distraction was assessed with the following two questions: Were you able to concentrate suf ciently on performing the taste test? and Did you feel distracted while performing the taste test?, both answered on a 7-point Likert scale (from very badly to very well and from not at all to very much, respectively).

Restraint

Subjects were divided into groups of high and low restraint on the basis of a median split of their scores on the Restraint Scale (Polivy et al., 1978). This scale, a 10-item questionnaire that was designed to measure the level of dietary restraint contains questions on dieting, concerns about weight and eating, and weight variation over different time periods. The RS is well validated (Ruderman & Besbeas, 1992) and is widely used to identify restrained and unrestrained eaters, whose eating behaviour was successfully predicted in a series of laboratory studies (for an overview, see e.g. Ruderman, 1986).

Brigitte Boon et al.

Procedure

Participants were asked to have breakfast or lunch 13 hours before participation and to refrain from eating thereafter until the experiment. All subjects were tested individually. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the experimenter told the cover story that the test concerned differences in taste perception between people, with particular interest in the in uence of external factors, such as watching TV while eating. Participants were presented with three bowls of ice-cream, each containing approximately 600 g of vanilla, strawberr y or chocolate ice-cream. Participants were randomly assigned to either the high or low calorie condition. All participants were instructed to taste the three avours and to rate them on a rating form that would be handed to them after the taste test. They were told that they had to taste all the avours and to feel free to eat as much as they wanted and as much as they needed for reliable taste ratings. Participants were randomly assigned to the distraction or no-distraction condition. In the nodistraction condition they performed the taste test in a silent room. In the distraction condition, participants were informed that they had to perform a second task that consisted of listening to a radio conversation (see distraction). All participants were then left alone for 15 minutes in order to taste. After that, the experimenter returned and asked the participants to ll in a set of questionnaires (the distraction manipulation check, a taste rating form that contained the perceived calories manipulation check, questions about the purpose of the experiment, the Restraint Scale and a general questionnaire containing questions about age, study and time of lunch or breakfast). Participants height and weight were measured and they were debriefed, thanked and paid a small fee for participation. Ice-cream consumption was calculated by weighing the ice-cream bowls before and after the tasting.

Results

Manipulation checks The manipulation checks indicated that the manipulations of distraction and of perceived calorie content had been successful. Distracted participants reported that they were signi cantly less able to concentrate than not-distracted participants (M 4.5 (SD 1.2) vs. M 6.2 (SD 0.9); t(120) 5 2 8.9, p < .001). Distracted participants also indicated that they felt signi cantly more distracted than did not-distracted participants (M 4.5 (SD 1.5) vs. M 1.9 (SD 1.3); t(120) 5 10.5, p < .001). Similarly, participants in the low calorie condition perceived the ice-cream as signi cantly less calori c than did participants in the high calorie condition (M 4.4 (SD 1.7) vs. M 7.7 (SD 1.4); t(120) 5 11.8, p < .001). Consumption Table 2 shows the mean consumption for participants in the distraction and nodistraction conditions when eating ice-cream perceived as either low or high in calories. BMI was included as a covariate in all analyses, since our restrained eaters had a signi cantly higher BMI than our unrestrained eaters. A 2 (restraint) 3 2 (distraction) 3 2 (perceived calories) ANCOVA was conducted on consumption with BMI as a covariate. The effect of the BMI as covariate was not signi cant (F < 1). There was a main effect for distraction (F(1, 106) 5 17.7, p < .001) with participants eating more ice-cream under distraction rather than no-distraction conditions. There were no main effects for restraint (F < 1) and perceived calories (F < 1) and none of the two-way interactions reached signi cance. However, in line with predictions, there was a signi cant three-way interaction (F(1, 106) 5 4.4, p < .05). This interaction was clari ed by the results of two 2-factor (2 (restraint) 3 2 (distraction))

Ironic processes in eating behaviour Table 2. Mean consumption (g) for restrained and unrestrained eaters No distraction M High calorie Restrained Unrestrained Low calorie Restrained Unrestrained (SD) N M Distraction (SD)

154.6 176.0 186.0 175.1

(98.9) (77.5) (75.3) (97.0)

14 14 15 15

274.6 192.5 234.9 261.0

(96.9) (76.5) (95.2) (78.2)

14 14 13 16

ANOVAs conducted separately for the two calorie conditions. Within the high calorie condition, a signi cant main effect occurred for distraction (F(1, 51) 5 8.1, p < .01) with more ice-cream being eaten under distraction conditions. However, this main effect was moderated by a signi cant restraint 3 distraction interaction (F(1, 51) 5 4.7, p < .05). Thus, as tests of the simple effects con rm, whereas restrained eaters tended to eat slightlybut not signi cantlyless ice-cream than unrestrained eaters when not distracted (F(1, 52) 5 0.2, NS), they ate considerably more than unrestrained eaters when distracted (F(1, 52) 5 5.1, p < .05). In the low calorie condition, only the main effect of distraction reached signi cance (F(1, 54) 5 9.1, p < .01). There was no indication of an interaction between restraint and distraction (F < 1) within the low calorie condition. In order to further clarify the effects of the distraction, post hoc tests of all four simple effects were conducted. These revealed that two of the four groups ate more in the distraction condition than their counterparts in the no-distraction condition; the restrained eaters in the high calorie condition (F(1, 106) 5 12.9, p < .001) and the unrestrained eaters in the low calorie condition (F(1, 106) 5 7.5, p < .05).

Discussion

Most of the ndings of the present study are consistent with our predictions, but some are not and these form an interesting puzzle which needs further exploration. The major hypothesis tested in our study was that of an interaction between restraint, distraction, and the perceived calorie content of the food stimuli. We expected that impairment of cognitive capacity would lead to overeating in restrainedbut not in unrestrained eaters and that this difference should only emerge with food which was high in calories. This prediction was supported in separate analyses for the conditions in which the ice-cream was perceived to be high vs. low in calories. For the low calorie condition, no restraint 3 distraction interaction was predicted. Consistent with this hypothesis, no such interaction was found. In the condition in which the ice-cream was perceived to be high in calories, we did predict and nd a restraint 3 distraction interaction. Restrained participants ate the same amount as unrestrained participants in the no-distraction condition, but substantially more than unrestrained individuals in the distraction condition. The consumption of the distracted

Brigitte Boon et al.

restrained eaters was also signi cantly larger than that of the restrained eaters who had not been distracted. Thus, as predicted from Ironic Process Theory, restrained eaters were successful in realizing their intention to eat little of the high-calorie food if they were not distracted. Apparently the ability to bring their full cognitive resources to bear on the task enables restrained eaters to control their eating. However, as in other tests of the Ironic Process Theory (Wegner, 1994), if they were distracted and thus had to deal with cognitive capacity limitations, their attempts to control their eating appeared to have the ironic effect of resulting in higher consumption. Contrary to expectation, however, there was also a main effect of distraction. Restrained as well as unrestrained eaters consumed more ice-cream in the distraction than in the no-distraction condition. This nding for the unrestrained eaters was neither predicted from Ironic Process Theory (Wegner, 1994), nor can it be derived from the Boundary Model of Herman and Polivy (1984). Both theories would predict that unrestrained eaters would not be affected by distraction, since they are not assumed to regulate their eating behaviour cognitively. A potential interpretation of the overall main effect of distraction could be derived from Epsteins research on salivary responses to food cues under conditions of distraction (Epstein, Mitchell & Caggiula, 1993; Epstein, Paluch, Smith & Sayette, 1997). Their ndings revealed that attending to environmental stimuli in an attentionally demanding task slows down the process of habituation to repeated presentations of food cues, as indicated by a signi cant deceleration of the decrease in levels of salivation. They concluded that an implication of this nding is that tasks that require signi cant information processing may slow down habituation to sensory properties of food cues, such that an individual might eat more when involved in cognitively demanding tasks than when allocating the majority of cognitive processing resources to food cues (Epstein et al., 1993, 1997, p. 63). This effect, then, should be found in restrained as well as unrestrained eaters. Unfortunately, Epstein and colleagues did not differentiate between restrained and unrestrained eaters. To validate this hypothesis, a study is needed which examines the salivary responses as well as actual food consumption of restrained and unrestrained eaters under conditions of high or low cognitive load and with repeated presentation of food cues. A second possible explanation for the nding that unrestrained eaters, as well as restrained eaters, showed a higher consumption in distraction than in no-distraction conditions is that unrestrained eaters too may pay at least some attention to cognitive cues in regulating their eating behaviour. This assumption would be consistent with ndings from Boon, Stroebe, Schut, and Jansen (1998), indicating that unrestrained eaters do attend to calorie information. Both restrained eaters and unrestrained eaters, who had been asked to write down their thoughts elicited by food words presented to them, responded with more restraint-relevant thoughts (e.g. I should not eat this or This contains many calories) to words describing high rather than low calorie food items. This would suggest that unrestrained eaters are not as unrestrained as they were assumed to be. However, this interpretation would be dif cult to reconcile with the many studies that have shown differences in the behaviour of restrained and unrestrained eaters. On the whole, our application of the Ironic Process Theory to restrained eating resulted in interesting and novel ndings concerning the overeating of restrained eaters. Even though we cannot yet offer any conclusive explanation for the disinhibitive overall main effect of distraction, we did nd support for the limited capacity hypothesis. Restrained eaters who were distracted ate more of the (forbidden) high calorie ice-

Ironic processes in eating behaviour

cream than did unrestrained eaters who were distracted. Their consumption was also higher than that of restrained eaters who were not distracted. This may imply that the nature of the distraction is not important and can be either emotional or non-emotional. If restrained eaters do not have full access to their cognitive resources, they may be sensitive to ironic processes that lead them to overeat. Herman and Polivys suggestion that negative emotions are a more urgent concern than dieting may thus be true for a number of factors in addition to negative emotional states. To avoid premature conclusions, however, it should be remembered that the present experiment did not include a measure of negative affect. The possibility that distraction had its effect on consumption via the induction of negative affectdue to the frustrating or annoying experience of having to perform two tasks simultaneously, for examplecannot be completely ruled out. An implication of the present ndingsif attributed to distraction and not to negative affectis that the more that restrained eaters try to exert control over their eating behaviour (e.g. when high calorie food is present), the higher will be their vulnerability for the unintended consequence, namely overeating. Since the risk of being cognitively distracted is pervasive, this would induce repeated overeating. Eating in front of the television, conversations while having dinner, may limit the available cognitive resources needed to restrain high calori c food intake. This may explain ndings such as those of Klesges et al. (1992), indicating that many dieters are unsuccessful and end up gaining weight instead of losing it.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof Dr. D. M. Wegner, Prof Dr. A. Jansen and Dr. M. Stroebe for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

References

Baucom, D. H., & Aiken, P. A. (1981). Effect of depressed mood on eating among obese and nonobese, dieting and nondieting persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 577585. Boon, B. (1998). Why dieters overeat: On the cognitive regulation of eating behaviour. Doctoral dissertation, Amsterdam. Boon, B., Stroebe, W., Schut, H., & Jansen, A. (1997). Does cognitive distraction lead to overeating in restrained eaters? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25, 319 327. Boon, B., Stroebe, W., Schut, H., & Jansen, A. (1998). Food for thought: Cognitive regulation of food intake. British Journal of Health Psychology, 3, 2740. Cools, J., Schotte, D. E., & McNally, R. J. (1992). Emotional arousal and overeating in restrained eaters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 348351. Cooper, P. J., & Bowskill, R. (1986). Dysphoric mood and overeating. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25, 155156. Epstein, L. H., Mitchell, S. L., & Caggiula, A. R. (1993). The effect of subjective and physiological arousal on dishabituation of salivation. Physiology and Behavior, 53, 593597. Epstein, L. H., Paluch, R., Smith, D. J., & Sayette, M. (1997). Allocation of attentional resources during habituation to food cues. Psychophysiology, 34, 5964. Frost, R. O., Goolkasian, G. A., Ely, R. J., & Blanchard, F. A. (1982). Depression, restraint and eating behaviour. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 20, 113 121. Green, M. W., Elliman, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1997). Impaired cognitive processing in dieters: Failure of attention focus or resource capacity limitation? British Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 259267.

10

Brigitte Boon et al.

Heatherton, T. E., & Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Binge eating as an escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 86 108. Herman, C. P., & Mack, D. (1975). Restrained and unrestrained eating. Journal of Personality, 43, 647 660. Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1975). Anxiety, restraint and eating behaviour. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 84, 666672. Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1984). A Boundary Model for the regulation of eating. In A. J. Stunkard & E. Stellar (Eds.), Eating and its disorders (pp. 141156). New York: Raven Press. Jansen, A., Oosterlaan, J., Merckelbach, H., & Hout, M. A. van den (1988). Nonregulation of food intake in restrained emotional and external eaters. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 10, 345353. Klesges, R. C., Isbell, T. R., & Klesges, L. M. (1992). Relationship between dietary restraint, energy intake, physical activity and body weight: A prospective analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 668674. Lowe, M. R. (1993). The effects of dieting on eating behaviour: A three-factor model. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 100121. Polivy, J., Herman, C. P., & McFarlane, T. (1994). Effects of anxiety on eating: Does palatability moderate distress-induced overeating in dieters? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 505 510. Polivy, J., Herman, C. P., & Warsh, S. (1978). Internal and external components of emotionality in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 497504. Ruderman, A. J. (1985). Dysphoric mood and overeating: A test of restraint theorys disinhibition hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 7885. Ruderman, A. J. (1986). Dietary restraint: A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 247262. Ruderman, A. J., & Besbeas, M. (1992). Psychological characteristics of dieters and bulimics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 92, 210215. Schotte, D. E., Cools, J., & McNally, R. J. (1990). Film-induced negative affect triggers overeating in restrained eaters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 317320. Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101, 3452. Wegner, D. M., & Erber, R. (1993). Social foundations of mental control. In D. M. Wegner & J. W. Pennebaker (Eds.), Handbook of mental control (pp. 3656). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. Wegner, D. M., Erber, R., & Zanakos, S. (1993). Ironic processes in the mental control of mood and mood-related thought. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 10931104. Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., III, & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 513. Received 14 May 1999; revised version received 11 August 2000

You might also like

- Master ASL - Level OneDocument428 pagesMaster ASL - Level OneBrian Blackwell100% (2)

- Cosmic Kids 1 Workbook PDFDocument96 pagesCosmic Kids 1 Workbook PDFOtilia Rusu100% (1)

- Sweet Lies: Neural, Visual, and Behavioral Measures Reveal A Lack of Self-Control Conflict During Food Choice in Weight-Concerned WomenDocument11 pagesSweet Lies: Neural, Visual, and Behavioral Measures Reveal A Lack of Self-Control Conflict During Food Choice in Weight-Concerned WomenTetsuo MatsunagaNo ratings yet

- Eating Behavior, Personality Traits and Body Mass in WomenDocument11 pagesEating Behavior, Personality Traits and Body Mass in WomenAnonymous 4zjaWXBcNo ratings yet

- Vans Trien 1986Document21 pagesVans Trien 1986Anonymous 4zjaWXBcNo ratings yet

- The Emotional Eating ScaleDocument13 pagesThe Emotional Eating Scalegyaiff100% (2)

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Eating DisordersDocument42 pagesCognitive Behaviour Therapy For Eating DisordersManya Krishna100% (1)

- PHD 23600 Review Serin (A)Document12 pagesPHD 23600 Review Serin (A)Rita FerreiraNo ratings yet

- J Physbeh 2020 113307Document11 pagesJ Physbeh 2020 113307Ma José EstébanezNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Mood On Food Versus Non-Food Interference Among Females Who Are High and Low On Emotional EatingDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Mood On Food Versus Non-Food Interference Among Females Who Are High and Low On Emotional EatingMilagros ArguedasNo ratings yet

- Smitham Intuitive Eating Efficacy Bed 02 16 09Document43 pagesSmitham Intuitive Eating Efficacy Bed 02 16 09Evelyn Tribole, MS, RDNo ratings yet

- Exemplu de Studiu Calitativ Prin Metoda Interviului (2) FișierDocument10 pagesExemplu de Studiu Calitativ Prin Metoda Interviului (2) Fișierioana Ungurianu2No ratings yet

- "Transdiagnostic" Theory and Treatment FairburnDocument20 pages"Transdiagnostic" Theory and Treatment FairburnMelisa RosenNo ratings yet

- The Role of Dietary Restriction in Binge EatingDocument11 pagesThe Role of Dietary Restriction in Binge EatingSofie WiddershovenNo ratings yet

- Mount Carmel College: Sara Athar MA171256 B.A. HonsDocument21 pagesMount Carmel College: Sara Athar MA171256 B.A. HonsSara AtharNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions For Obesity-Related Eating Behaviors: A Literature ReviewDocument20 pagesMindfulness-Based Interventions For Obesity-Related Eating Behaviors: A Literature ReviewEliseia CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Control of OvereatingDocument9 pagesBehavioral Control of OvereatingDario FriasNo ratings yet

- Dieting and The Self-ControlDocument17 pagesDieting and The Self-ControlFederico FiorentinoNo ratings yet

- Dealing With Problematic Eating BehaviouDocument5 pagesDealing With Problematic Eating BehaviouDalm DuduNo ratings yet

- Coping With Food Cravings InvestigatingDocument4 pagesCoping With Food Cravings InvestigatingDalm DuduNo ratings yet

- Canetti, Bachar, & Berry, 2002Document8 pagesCanetti, Bachar, & Berry, 2002Ana Sofia AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Can't Control Yourself? Monitor Those Bad Habits Jeffrey M. Quinn, Anthony Pascoe, Wendy Wood, and David T. Neal Duke UniversityDocument43 pagesCan't Control Yourself? Monitor Those Bad Habits Jeffrey M. Quinn, Anthony Pascoe, Wendy Wood, and David T. Neal Duke UniversitybhanuprakashbhadariaNo ratings yet

- Binge Eating As Escape From Self-Awareness: Todd E HeathertonDocument23 pagesBinge Eating As Escape From Self-Awareness: Todd E HeathertonEliza MartinNo ratings yet

- Food Addiction in Humans PDFDocument3 pagesFood Addiction in Humans PDFFrater IgnatiusNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Thesis On Eating DisordersDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Thesis On Eating Disordersp0zikiwyfyb2100% (1)

- Manuscript 30 11 v2Document51 pagesManuscript 30 11 v2Juliana Therese T. MulletaNo ratings yet

- Resume Chpter7Document3 pagesResume Chpter7Nadia Islami Nur FadillaNo ratings yet

- Desmet & Schifferstein Sources of Emotions in Food Experience 2007Document12 pagesDesmet & Schifferstein Sources of Emotions in Food Experience 2007Ricardo YudiNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Control of EatingDocument10 pagesCognitive Control of EatingCamilla MendesNo ratings yet

- TMP F357Document21 pagesTMP F357FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Seguias and Tapper 2018 PrepubDocument23 pagesSeguias and Tapper 2018 PrepubMyraChNo ratings yet

- Kristeller, J. & Epel, E. (2014) - Mindful Eating and Mindless Eating: The Science and The Practice.Document11 pagesKristeller, J. & Epel, E. (2014) - Mindful Eating and Mindless Eating: The Science and The Practice.Jean KristellerNo ratings yet

- Mcmanus 1995Document19 pagesMcmanus 1995isadoraNo ratings yet

- st20240126 PSY5204 WRIT2Document6 pagesst20240126 PSY5204 WRIT2Astrid FernandesNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Models of EatingDocument11 pagesCognitive Models of Eating-sparkle1234No ratings yet

- Chocolate Cake. Guilt or Celebration? Associations With Healthy Eating Attitudes, Perceived Behavioural Control, Intentions and Weight-LossDocument7 pagesChocolate Cake. Guilt or Celebration? Associations With Healthy Eating Attitudes, Perceived Behavioural Control, Intentions and Weight-LossThanit Paopao VinitchagoonNo ratings yet

- Uncontrolled Eating: A Unifying Heritable Trait Linked With Obesity, Overeating, Personality and The BrainDocument16 pagesUncontrolled Eating: A Unifying Heritable Trait Linked With Obesity, Overeating, Personality and The BrainbaloomTTRNo ratings yet

- Reichenberger 2018 N HM TaDocument9 pagesReichenberger 2018 N HM Tapriscila scoassanteNo ratings yet

- Trabajo de InglesDocument11 pagesTrabajo de Inglesanhell182No ratings yet

- Introduction FinalDocument8 pagesIntroduction FinalCarl Allen MancaoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document4 pagesAssignment 2Amina IftikharNo ratings yet

- Theoretical, Practical, and Social Issues in Behavioral Treatments of ObesityDocument23 pagesTheoretical, Practical, and Social Issues in Behavioral Treatments of ObesityJoão P. RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Causes of Emotional Eating and Matched Treatment of ObesityDocument8 pagesCauses of Emotional Eating and Matched Treatment of ObesitySyafrie YunizarNo ratings yet

- Berthoud, Proc Nutr Soc, 2012Document16 pagesBerthoud, Proc Nutr Soc, 2012Dianne Faye ManabatNo ratings yet

- Psych 114 Rough DraftDocument7 pagesPsych 114 Rough DraftRajvinder BrarNo ratings yet

- Testing A Mobile Mindful Eating Intervention Targeting Craving-Related Eating: Feasibility and Proof of ConceptDocument14 pagesTesting A Mobile Mindful Eating Intervention Targeting Craving-Related Eating: Feasibility and Proof of ConceptMuhammad SuhaeriNo ratings yet

- Lombardo2021 Article EatingSelf-efficacyValidationODocument9 pagesLombardo2021 Article EatingSelf-efficacyValidationOCEDIAMET UMANNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Combined Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Hypnotherapy in Anorexia Nervosa A Case StudyDocument8 pagesEfficacy of Combined Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Hypnotherapy in Anorexia Nervosa A Case StudyCarol Rio AguirreNo ratings yet

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy For Binge-Eating DisorderDocument14 pagesDialectical Behavior Therapy For Binge-Eating DisorderelioraNo ratings yet

- ADICCIÓN Comida, ConceptoDocument8 pagesADICCIÓN Comida, Conceptoadriannn017No ratings yet

- Sleep Medicine: Julia Burt, Laurette Dube, Louise Thibault, Reut GruberDocument5 pagesSleep Medicine: Julia Burt, Laurette Dube, Louise Thibault, Reut GrubermerawatidyahsepitaNo ratings yet

- Physical Healing As A Function of Perceived Time: Peter Aungle & Ellen LangerDocument9 pagesPhysical Healing As A Function of Perceived Time: Peter Aungle & Ellen Langertincho1980No ratings yet

- Causes of Emotional EatingDocument8 pagesCauses of Emotional EatingLarissa FernandesNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Neuroscience of 2018Document17 pagesCognitive Neuroscience of 2018Dhino Armand Quispe SánchezNo ratings yet

- Effects of Placebo Interventions On Subjective and Objective Markers of Appetite-A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesEffects of Placebo Interventions On Subjective and Objective Markers of Appetite-A Randomized Controlled TrialMaria NeumaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Eating PDFDocument22 pagesEmotional Eating PDFGabriela Alejandra Milne EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Bilici Et Al. 2020 PDFDocument6 pagesBilici Et Al. 2020 PDFelioraNo ratings yet

- Coulthard Et Al, 2023Document23 pagesCoulthard Et Al, 2023florinacretuNo ratings yet

- Warren 2017Document12 pagesWarren 2017pimpamtomalacasitosNo ratings yet

- Integral Nutritional Guide: The Encyclopedia of the Ideas about NutritionFrom EverandIntegral Nutritional Guide: The Encyclopedia of the Ideas about NutritionNo ratings yet

- The Better Brain: Overcome Anxiety, Combat Depression, and Reduce ADHD and Stress with NutritionFrom EverandThe Better Brain: Overcome Anxiety, Combat Depression, and Reduce ADHD and Stress with NutritionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Autonomic Nervous System & Homeopathy: Personalized Nutrition Concept Depicted in Homeopathy & AyurvedaFrom EverandAutonomic Nervous System & Homeopathy: Personalized Nutrition Concept Depicted in Homeopathy & AyurvedaNo ratings yet

- 0057 Primary E2L Stage 4 Scheme of Work - tcm142-595034Document51 pages0057 Primary E2L Stage 4 Scheme of Work - tcm142-595034Luis Ernesto NavarreteNo ratings yet

- Massage For Therapists A Guide To Soft Tissue Therapies: October 2010Document3 pagesMassage For Therapists A Guide To Soft Tissue Therapies: October 2010reza ghazizadeNo ratings yet

- Vihit Namuna Annexure-XV - 270921Document1 pageVihit Namuna Annexure-XV - 270921Rajendra JangleNo ratings yet

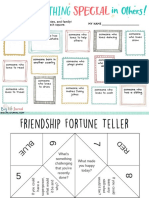

- Get To Know Your Friends, Classmates, and Family! Write The Person's Name Inside Each SquareDocument4 pagesGet To Know Your Friends, Classmates, and Family! Write The Person's Name Inside Each Squareanasi19100% (1)

- Grade 6 English Reading Using The Dictionary To Select The Appropriate Meaning From Several MeaningsDocument6 pagesGrade 6 English Reading Using The Dictionary To Select The Appropriate Meaning From Several MeaningsMisyel CamposanoNo ratings yet

- Fuzzy Decision MakingDocument45 pagesFuzzy Decision Makingraghu kiranNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Simulation and ReflectionDocument4 pagesModule 6 Simulation and Reflectionapi-693298996No ratings yet

- DLL-ENG8-Second Quarer Week 4 - EditedDocument9 pagesDLL-ENG8-Second Quarer Week 4 - EditedDiana Mariano - CalayagNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document4 pagesChapter 1fatemehNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ CHỌN ĐỘI TUYỂN ANH 10 - DATE 4-12-2021Document16 pagesĐỀ CHỌN ĐỘI TUYỂN ANH 10 - DATE 4-12-2021Linh PhươngNo ratings yet

- The Act Course Book: English, Reading, & WritingDocument37 pagesThe Act Course Book: English, Reading, & WritingOla GabrNo ratings yet

- 2023 DAC InvitedDocument2 pages2023 DAC Invitedibrahimmmmmmmmmm855No ratings yet

- Teaching: 1. PhilosophyDocument2 pagesTeaching: 1. Philosophydoggaravi07No ratings yet

- Learning To Program - Difficulties and Solutions: January 2007Document6 pagesLearning To Program - Difficulties and Solutions: January 2007Gustavo EcheverryNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Examination in Advanced Educational PsychologyDocument5 pagesComprehensive Examination in Advanced Educational PsychologyKaela Lor100% (1)

- Notes Toward An Aesthetic Popular Culture: by His byDocument14 pagesNotes Toward An Aesthetic Popular Culture: by His bySándor KálaiNo ratings yet

- ENG2602 Assignment 01Document6 pagesENG2602 Assignment 01zongamele50% (2)

- Addendum Modbus/TCP Communications Board.: Scroll 9600 No Parity 1 8 Modbus Disabled 1 NoneDocument8 pagesAddendum Modbus/TCP Communications Board.: Scroll 9600 No Parity 1 8 Modbus Disabled 1 NoneDan Hidalgo QuintoNo ratings yet

- What Is The Purpose of Pre-Reading Activities?Document8 pagesWhat Is The Purpose of Pre-Reading Activities?Sylvaen WswNo ratings yet

- Steps Towards Personalised Learner Management System (LMS) : SCORM ImplementationDocument15 pagesSteps Towards Personalised Learner Management System (LMS) : SCORM ImplementationRousha_itiNo ratings yet

- Main Idea Survival PacketDocument26 pagesMain Idea Survival PacketFigueroa Picart0% (1)

- FCE WritingDocument24 pagesFCE WritingQuil Réjane100% (1)

- Curriculum MapDocument1 pageCurriculum MapAnonymous xVTbc3T6No ratings yet

- Level of Application and Effectiveness of General TheoriesDocument32 pagesLevel of Application and Effectiveness of General TheoriesNormi Anne TuazonNo ratings yet

- 3PAR Service Processor Users Guide 2011 04 PDFDocument80 pages3PAR Service Processor Users Guide 2011 04 PDFpaladina7833No ratings yet

- Ashutosh PandeyDocument2 pagesAshutosh PandeySubodh KumarNo ratings yet

- UIIC Assistant Result 2024Document7 pagesUIIC Assistant Result 2024allenimmanuel1973No ratings yet

- Northouse8e PPT 05Document22 pagesNorthouse8e PPT 05Grant imaharaNo ratings yet