Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SarbanesOxleyart4 06 Strong

SarbanesOxleyart4 06 Strong

Uploaded by

plaw15Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Affidavit of Corporate DenialDocument9 pagesAffidavit of Corporate DenialHOPE6582% (11)

- Intelligent Business AdvancedDocument196 pagesIntelligent Business Advancedlrt60% (5)

- Linda Wall Wins Over IRSDocument12 pagesLinda Wall Wins Over IRSJeff Anderson89% (9)

- Trusts: Fertile Field For Philippine Jurisprudence: by Vicente Abad SantosDocument8 pagesTrusts: Fertile Field For Philippine Jurisprudence: by Vicente Abad SantosJunelyn T. EllaNo ratings yet

- CLV - Law On TrustsDocument52 pagesCLV - Law On TrustsBless Carpena100% (7)

- Motion To Consolidate (Eviction Into Quiet Title)Document5 pagesMotion To Consolidate (Eviction Into Quiet Title)plaw15100% (1)

- Certified Sarbanes-Oxley Expert (CSOE) Distance Learning and Online Certification Program PDFDocument12 pagesCertified Sarbanes-Oxley Expert (CSOE) Distance Learning and Online Certification Program PDFApoorva BadolaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 - Test BankDocument35 pagesChapter 18 - Test Bankjuan100% (2)

- Case Digest Benedicto vs. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesCase Digest Benedicto vs. Court of AppealsMichelle VillamoraNo ratings yet

- Rod Filing Traffic CaseDocument11 pagesRod Filing Traffic Caserodclassteam100% (2)

- Legal Words You Should Know: Over 1,000 Essential Terms to Understand Contracts, Wills, and the Legal SystemFrom EverandLegal Words You Should Know: Over 1,000 Essential Terms to Understand Contracts, Wills, and the Legal SystemRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- PL MSJ & Response To Def MSJDocument13 pagesPL MSJ & Response To Def MSJAC Field100% (2)

- Internal Audit Manager in Dallas FT Worth TX Resume Charles MoffattDocument1 pageInternal Audit Manager in Dallas FT Worth TX Resume Charles MoffattCharlesMoffattNo ratings yet

- Running Head: SARBANES-OXLEY ACT 1Document4 pagesRunning Head: SARBANES-OXLEY ACT 1twalkthis069No ratings yet

- Demand For Verified Evidence of "Trade or Business" Activity: Currency Transaction Report (CTR) InstructionsDocument19 pagesDemand For Verified Evidence of "Trade or Business" Activity: Currency Transaction Report (CTR) InstructionsShawn Psenicnik (ShawniP)No ratings yet

- United States v. Bramblett, 348 U.S. 503 (1955)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Bramblett, 348 U.S. 503 (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eo 99111 22Document5 pagesEo 99111 22Kaylee SteinNo ratings yet

- Bill of Attainder-Ex Post Facto LawDocument4 pagesBill of Attainder-Ex Post Facto LawMeriem Grace RiveraNo ratings yet

- Bank Secrecy LawDocument6 pagesBank Secrecy LawAilaMarieB.QuintoNo ratings yet

- Estrada Vs SandiganbayanDocument198 pagesEstrada Vs Sandiganbayanangelica poNo ratings yet

- Counterfeit Securities DismissDocument24 pagesCounterfeit Securities DismissShane Christopher100% (3)

- People v. Rosenthal & OsmenaDocument3 pagesPeople v. Rosenthal & OsmenaBoy Omar Garangan DatudaculaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam-Paralegal WorkDocument4 pagesFinal Exam-Paralegal WorkPegalongan ESNo ratings yet

- Aris - Echavez DigestDocument18 pagesAris - Echavez DigestMykee AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction Chapter 5 SummaryDocument10 pagesStatutory Construction Chapter 5 SummaryBrian Balio100% (1)

- (DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - Quill - Letter #L8080 - Follow Up Letter On Interpretation of Willful - Version #2!02!15-2023 at 12-04 PMDocument8 pages(DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - Quill - Letter #L8080 - Follow Up Letter On Interpretation of Willful - Version #2!02!15-2023 at 12-04 PMHenry RodgersNo ratings yet

- DocStatutory Construction Case DigestDocument14 pagesDocStatutory Construction Case DigestDieanne MaeNo ratings yet

- Simple Treaty of ProtectionDocument8 pagesSimple Treaty of ProtectionJack MeHoffNo ratings yet

- Constructive Notice CADocument18 pagesConstructive Notice CAMike SmithNo ratings yet

- Civil ForfeitureDocument9 pagesCivil ForfeituresummermangoNo ratings yet

- 278 Scra 27Document1 page278 Scra 27Jun Rinon100% (1)

- Ligot Vs RepublicDocument5 pagesLigot Vs RepublicPaolo MendioroNo ratings yet

- 2001 Estrada - v. - Sandiganbayan20170221 898 Uz1rrp PDFDocument153 pages2001 Estrada - v. - Sandiganbayan20170221 898 Uz1rrp PDFMau AntallanNo ratings yet

- Republic V Eugenio Case DigestDocument4 pagesRepublic V Eugenio Case DigestFaye Allen Matas50% (2)

- United States v. Evans, 333 U.S. 483 (1948)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Evans, 333 U.S. 483 (1948)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Corpo DigestsDocument21 pagesCorpo DigestsJf ManejaNo ratings yet

- Engel v. O'MALLEY, 219 U.S. 128 (1911)Document5 pagesEngel v. O'MALLEY, 219 U.S. 128 (1911)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Civil Forfeiture Proceedings in The Philippines PDFDocument28 pagesCivil Forfeiture Proceedings in The Philippines PDFArjane Aram Samaniego100% (1)

- Ricarze Vs CADocument3 pagesRicarze Vs CACarl LawsonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008Document5 pagesG.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008hudor tunnelNo ratings yet

- AgPart 925 - TrustDocument130 pagesAgPart 925 - Trustcezar delailaniNo ratings yet

- STATCON CASE DIGEST 5 Nov. 24,2020Document36 pagesSTATCON CASE DIGEST 5 Nov. 24,2020credit analystNo ratings yet

- Estrada vs. Sandiganbayan'Document3 pagesEstrada vs. Sandiganbayan'Carla January OngNo ratings yet

- Sereno - Quo Warranto V ImpeachmentDocument3 pagesSereno - Quo Warranto V ImpeachmentJM PabustanNo ratings yet

- Impossible For The Judges Who Issued The Warrants To Have Found The Existence of Probable CauseDocument2 pagesImpossible For The Judges Who Issued The Warrants To Have Found The Existence of Probable CauselividNo ratings yet

- False Statements and Perjury: An Overview of Federal Criminal LawDocument24 pagesFalse Statements and Perjury: An Overview of Federal Criminal LawlllNo ratings yet

- Secrecy of Bank Deposits Law-NotesDocument5 pagesSecrecy of Bank Deposits Law-Notesjb_uy50% (2)

- University of The Philippines College of Law: Estrada V. SandiganbayanDocument6 pagesUniversity of The Philippines College of Law: Estrada V. SandiganbayanJelly BerryNo ratings yet

- Clovis Carl GREEN., JR., Petitioner, v. Honorable Edward W. NOTTINGHAM, District Judge Honorable Richard M. Borchers, Magistrate Judge, RespondentsDocument9 pagesClovis Carl GREEN., JR., Petitioner, v. Honorable Edward W. NOTTINGHAM, District Judge Honorable Richard M. Borchers, Magistrate Judge, RespondentsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Broward County - Notice of Claim and Claim of Damages-MAD-ArrestDocument12 pagesBroward County - Notice of Claim and Claim of Damages-MAD-ArrestHakeem100% (1)

- One Man Out Actual and Constructive NoticeDocument4 pagesOne Man Out Actual and Constructive NoticeRb100% (8)

- Churchill Vs TaftDocument10 pagesChurchill Vs TaftRhea Lyn MalapadNo ratings yet

- The Main Points of Difference Between The Bribery Act and The FPCADocument2 pagesThe Main Points of Difference Between The Bribery Act and The FPCAShobikaNo ratings yet

- Senate Bill 1056: Maryland Second Chance Act of 2014Document7 pagesSenate Bill 1056: Maryland Second Chance Act of 2014abc2newsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Bisceglia, 420 U.S. 141 (1975)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Bisceglia, 420 U.S. 141 (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Corporations-Officers and Directors-Liability For RepresentativeDocument9 pagesCorporations-Officers and Directors-Liability For Representativenirmalaradhakrishna18No ratings yet

- The Main Issue - IntegrityDocument12 pagesThe Main Issue - IntegrityNoreen T� ClaroNo ratings yet

- 42 Usc 1983Document15 pages42 Usc 1983CrystalmorganstudentNo ratings yet

- 2001 Estrada v. SandiganbahyanDocument154 pages2001 Estrada v. SandiganbahyanChristine Ang CaminadeNo ratings yet

- Bar Journal ArticleDocument10 pagesBar Journal ArticleD B Karron, PhDNo ratings yet

- Dealing With Federal Tax Liens Filed IllegallyDocument10 pagesDealing With Federal Tax Liens Filed IllegallyDonna Eubank Helm100% (1)

- (G.R. No. 94723) Case DigestDocument2 pages(G.R. No. 94723) Case Digestlawnotesnijan100% (4)

- ESTRADA vs. SandiganbayanDocument4 pagesESTRADA vs. SandiganbayanJoycee ArmilloNo ratings yet

- Constitution of the State of Minnesota — 1964 VersionFrom EverandConstitution of the State of Minnesota — 1964 VersionNo ratings yet

- Constitution of the State of Minnesota — 1960 VersionFrom EverandConstitution of the State of Minnesota — 1960 VersionNo ratings yet

- Cloud On TitleDocument1 pageCloud On Titleplaw15No ratings yet

- Lehman Brothers Lawsuit Trust BNC 3Document135 pagesLehman Brothers Lawsuit Trust BNC 3plaw15No ratings yet

- Breach of Fiduciary ResponsibilitiesDocument108 pagesBreach of Fiduciary Responsibilitiesplaw15100% (2)

- 3-11-09 Clerk Dorothy Brown Alerts ObamaDocument2 pages3-11-09 Clerk Dorothy Brown Alerts Obamaplaw15No ratings yet

- Mortgage-Mediation-Program-Factsheet 8 13 10Document2 pagesMortgage-Mediation-Program-Factsheet 8 13 10plaw15No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Control and AccountingDocument53 pagesChapter 4 - Control and AccountingLê Thái VyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Auditing and Assurance Services: Both Certified by 3 PartiesDocument13 pagesChapter 1 - Auditing and Assurance Services: Both Certified by 3 PartiescelineNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15Document4 pagesChapter 15helennguyen242004No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Business Its Legal Ethical and Global Environment 9th Edition JenningsDocument19 pagesTest Bank For Business Its Legal Ethical and Global Environment 9th Edition Jenningsa549795291No ratings yet

- Ais Chapter 7Document20 pagesAis Chapter 7CiaRa GinetaNo ratings yet

- (Control & AIS) Kelompok 2Document24 pages(Control & AIS) Kelompok 2AjiNo ratings yet

- Hyperion Financial ManagementDocument8 pagesHyperion Financial Managementsriuae1982No ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Multiple ChoiceDocument10 pagesCorporate Governance Multiple ChoiceAysha RiyaNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics ExamDocument7 pagesBusiness Ethics Exam明 志No ratings yet

- CISA Practice Questions To Prep For The Exam - TechTargetDocument9 pagesCISA Practice Questions To Prep For The Exam - TechTargetbirish2009No ratings yet

- 33 Yrs Audit Research FinalDocument133 pages33 Yrs Audit Research FinalRatna SaridewiNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 2Document4 pagesAssignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 2Haris MunirNo ratings yet

- Leadership Ethics and The Integrity Capacity ChallengeDocument38 pagesLeadership Ethics and The Integrity Capacity ChallengeJP De LeonNo ratings yet

- Powersc PDFDocument50 pagesPowersc PDFMauricio LocatelliNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument13 pagesAbstractKhooshal Yadhav RamphulNo ratings yet

- AWS Answers To Key Compliance QuestionsDocument12 pagesAWS Answers To Key Compliance Questionssparta21No ratings yet

- 25 - Evolution of Corporate Governance in India and AbroadDocument9 pages25 - Evolution of Corporate Governance in India and AbroadArunima SarkarNo ratings yet

- Accrual Based and Real Earnings Management Activities Around Seasoned Equity Offerings - 2010 - Journal of Accounting and Economics PDFDocument18 pagesAccrual Based and Real Earnings Management Activities Around Seasoned Equity Offerings - 2010 - Journal of Accounting and Economics PDFZhang PeilinNo ratings yet

- DOC-20240605-WA0012_Document21 pagesDOC-20240605-WA0012_Ayman AwadNo ratings yet

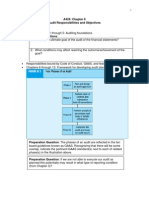

- A424: Chapter 6 Audit Responsibilities and Objectives Preparation QuestionsDocument8 pagesA424: Chapter 6 Audit Responsibilities and Objectives Preparation QuestionsNovah Mae Begaso SamarNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Part 1 Internal ControlDocument21 pagesModule 6 Part 1 Internal ControlKRISTINA CASSANDRA CUEVASNo ratings yet

- Related Party Transactions in Corporate Governance PDFDocument60 pagesRelated Party Transactions in Corporate Governance PDFfauziahNo ratings yet

- Question Text: Answer Saved Marked Out of 1.00Document10 pagesQuestion Text: Answer Saved Marked Out of 1.00angel diazNo ratings yet

- Juniper Networks Securities Fraud ComplaintDocument20 pagesJuniper Networks Securities Fraud ComplaintMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Financial Reporting and Analysis: AssignmentDocument4 pagesFinancial Reporting and Analysis: AssignmentXabi meerNo ratings yet

- Pe MCQSDocument53 pagesPe MCQSChris Rafel100% (2)

SarbanesOxleyart4 06 Strong

SarbanesOxleyart4 06 Strong

Uploaded by

plaw15Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SarbanesOxleyart4 06 Strong

SarbanesOxleyart4 06 Strong

Uploaded by

plaw15Copyright:

Available Formats

The Top Five Areas of Potential Criminal Exposure Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act by John R.

Teakell, Dallas, TX April 2006

When the Sarbanes -Oxley Act was passed in 2002, many people considered it a hurried reaction to corporate accounting scandals that had then repeatedly been front-page media stories. The act imposed significant new responsibilities on directors, officers and audit committees, along with potential criminal liability for violations of these new responsibilities. This writing is intended to identify five areas of potential criminal exposure within the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and not intended to fully discuss each area or offer solutions for each. There are five main areas that attorneys need to be aware of when advising their clients so that they may avoid criminal liability under Sarbanes-Oxley. These areas include: properly certifying periodic reports, never altering corporate documents, securities fraud, the whistleblower provision, and avoiding obstruction of justice charges. Although the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) may never seek criminal penalties during the course of an investigation, the SEC may refer the matter to the Department of Justice (DOJ) as a grand jury referral, which could be prosecuted by the U.S. Attorneys Office. 1. Certifying Periodic Reports

Sections 906 and 302 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act enacted twin provisions of the United

States Code requiring certification by the CEOs and CFOs of corporate documents; these provisions are 18 U.S.C. 1350 and 15 U.S.C. 7241, respectively. Each section gives two levels of criminal penalties, depending upon whether the violation was knowing or willful. Under 18 U.S.C., all CEOs and CFOs certify, in writing, that every periodic report filed by their public company under 13(a) or 15(d) of the Exchange Act, fairly represents the financial condition of the company. 18 U.S.C. 1350 also provides criminal penalties of up to 20 years for willful violations and up to 10 years imprisonment for violations where the executive knowingly signed a false certification. Under 15 U.S.C. 7241, a principal executive officer of officers and principal financial officer of officers or persons performing similar functions, of a public company must certify each quarterly and annual report filed by the company under the new Exchange Act Rules 13(a) or 15(d). Furthermore, a separate certification must be provided for each certifying officer, and the language of the certification cannot be varied from the language contained in the statute. William D. Gould & Dale E. Short, The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and its Aftermath. Certification is made based on the knowledge of the certifying officer, and ignorance will not be a defense to a charge of falsely certifying a quarterly or annual report if the certifying officer should have known that the certification was false. Therefore, the implementation of 302 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act creates a heavy burden on the CEO and CFO to become personally aware of material information on a timely basis, and also makes it difficult to argue in any investigation that the CEO or CFO in fact had no knowledge of material information that was available. Kirkland & Ellis LLP, How CEOs, CFOs Can Avoid Criminal Exposure Under Sarbanes-Oxley Certification Provisions. 2

Unlike 906 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, most cases of false certifications under 302 will be pursued civilly through SEC proceedings, however the DOJ may seek to prosecute 302 violations under criminal statutes that prohibit the use of mail, telephones or Internet to commit fraud under 18 U.S.C. 1341 (mail fraud) or 18 U.S.C. 1343 (wire fraud). Furthermore, an officer who willfully makes a false Sarbanes-Oxley Act 302 certification may be liable for criminal violation of the Exchange Act, which results in a maximum of up to 20 years imprisonment and up to $5 million in fines, under 1106. It is important for certifying officers to document specific procedures required under the statute. It may be advisable to obtain written certification or representations from other officers and employees directly responsible for the information in the report. 2. Sarbanes-Oxley Act 807, enhances criminal penalties for securities fraud under 18 U.S.C. 1348 Section 807 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act enhances the criminal penalties for securities fraud under newly created 18 U.S.C. 1348 properly entitled Securities Fraud. 18 U.S.C. 1348 provides that: Whoever knowingly executes, or attempts to execute, a scheme or artifice to defraud any person in connection with any security of an issuer with a class of securities registered under section 12 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 781) or that is required to file reports under section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 780(d)); or to obtain, by means of false or fraudulent pretences, representations, or promises, any money or property in connection with the purchase or sale of any security of an issuer with a class of securities registered under section 12 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 781) or that is required to file reports under section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 780(d)); shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned not more than 25 years, or both. Although the Securities Exchange Act has made securities fraud punishable for several 3

decades, the new provision appears to make a prosecution easier. For example, the mens rea requirement under the new statute is knowledge, as compared with the willfulness requirement of the Exchange Act. 1348 also removed the requirement that the fraud be in connection with the purchase or sale of securities.

3.

Altering Corporate Documents

Two provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley were created to increase the governments ability to convict individuals for altering documents - 802 and 1102. 18 U.S.C. 1519, which is entitled Destruction, Alteration, or Falsification of Records in Federal Investigations and Bankruptcy was created under 802 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. 18 U.S.C. 1519 provides that: Whoever knowingly alters, destroys, mutilates, conceals, covers up, falsified, or makes a false entry in any record, document, or tangible object with the intent to impede, obstruct, or influence the investigation or proper administration of any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of the United States or any case filed under title 11, or in relation to or contemplation of any such matter or case, shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both. 18 U.S.C. 1519 increases the governments ability to prosecute obstruction of justice for alteration or destruction of documents. This improved ability stems from the key element intent to impede, obstruct, or influence the proper administration of any matter, which does not require a pending or concluded investigation against the individual or corporation for the crime to be proven. Creamer, 52-May Fed. Law. at 38. This is because the language of 1519 is broad enough to potentially cover the destruction of a companys documents before an investigation occurs. Furthermore, 1519 does not require a willful or corrupt state of mind, and thus the government may not need to establish that a defendant intended to violate a known legal duty.

Id. Sarbanes-Oxley 1102 increases the penalties for destruction or altering of corporate audit records by amending 18 U.S.C. 1512 entitled Tampering with a Record or Otherwise Impeding and Official Proceeding. 18 U.S.C. 1512 now contains the following new subsection: (c) Whoever corruptly alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the objects integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding; or otherwise obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both. The purpose of amending 1512 is to enhance the current obstruction of justice statute by eliminating the requirement that one who obstructs or impedes an official proceeding or alters documents must corruptly persuade another to obstruct or impede an official proceeding before being found guilty of obstruction of justice. Prior to the amendment, anyone who obstructed justice on his or her own without influencing or intimidating another could not be prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. 1512. 18 U.S.C. 1520, which also deals with destroying or tampering with corporate audit records, has similarly been enhanced. 4. Sarbanes-Oxley Act 1107 whistleblower provision supported under 18 U.S.C. 1513

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act prohibits companies from retaliating against employees who alert the government to possible SEC violations. In fact, 1107 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act makes it a crime for anyone to knowingly, with intent to retaliate, take actions against any person including retaliation in connection with the persons employment, in response to such person 5

providing truthful information to law enforcement regarding a possible federal offense. The punishment for retaliating includes a fine and imprisonment of not more than ten years pursuant to 18 U.S.C. 1513. 5. Obstruction of Justice, found in 18 U.S.C. 1001

Although not specifically included in Sarbanes-Oxley, the obstruction of justice statute commonly used (or commonly threatened) is 18 U.S.C 1001. This section has for many years been utilized to threaten prosecution if a person lies to a government official in any matter within the jurisdiction of the United States. Under 18 U.S.C. 1001, anyone who, makes a materially false, fictitious or fraudulent statement or representation can be fined and imprisoned for up to five years. Also, if a witness testifies falsely under oath before the SEC staff or other government proceeding, he or she may be subject to a perjury conviction. 18 U.S.C. 1621. Obstruction of justice, found under 18 U.S.C. 1001 and other provisions, is arguably easier to prove than some actual violations of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Obstruction of justice ranges from influencing a witness not to talk to law enforcement to destroying documents.

In conclusion, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act enhanced criminal prosecutions by focusing on false certifications of company statements, altering documents and potential obstruction of justice. Although publicly traded companies and their counsel must use caution regarding the process of document certification, and retention of certain documents, equally of concern is any statement made to an investigator or attorney for the government. A statement made about company procedures or actions, could potentially label the maker of the statement a subject of an 6

investigation, especially if taken out of context or if made when a government agency already has heightened suspicions about a companys activities. This evermore underscores the need for company officials and employees to retain counsel prior to meeting with government representatives.

You might also like

- Affidavit of Corporate DenialDocument9 pagesAffidavit of Corporate DenialHOPE6582% (11)

- Intelligent Business AdvancedDocument196 pagesIntelligent Business Advancedlrt60% (5)

- Linda Wall Wins Over IRSDocument12 pagesLinda Wall Wins Over IRSJeff Anderson89% (9)

- Trusts: Fertile Field For Philippine Jurisprudence: by Vicente Abad SantosDocument8 pagesTrusts: Fertile Field For Philippine Jurisprudence: by Vicente Abad SantosJunelyn T. EllaNo ratings yet

- CLV - Law On TrustsDocument52 pagesCLV - Law On TrustsBless Carpena100% (7)

- Motion To Consolidate (Eviction Into Quiet Title)Document5 pagesMotion To Consolidate (Eviction Into Quiet Title)plaw15100% (1)

- Certified Sarbanes-Oxley Expert (CSOE) Distance Learning and Online Certification Program PDFDocument12 pagesCertified Sarbanes-Oxley Expert (CSOE) Distance Learning and Online Certification Program PDFApoorva BadolaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 - Test BankDocument35 pagesChapter 18 - Test Bankjuan100% (2)

- Case Digest Benedicto vs. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesCase Digest Benedicto vs. Court of AppealsMichelle VillamoraNo ratings yet

- Rod Filing Traffic CaseDocument11 pagesRod Filing Traffic Caserodclassteam100% (2)

- Legal Words You Should Know: Over 1,000 Essential Terms to Understand Contracts, Wills, and the Legal SystemFrom EverandLegal Words You Should Know: Over 1,000 Essential Terms to Understand Contracts, Wills, and the Legal SystemRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- PL MSJ & Response To Def MSJDocument13 pagesPL MSJ & Response To Def MSJAC Field100% (2)

- Internal Audit Manager in Dallas FT Worth TX Resume Charles MoffattDocument1 pageInternal Audit Manager in Dallas FT Worth TX Resume Charles MoffattCharlesMoffattNo ratings yet

- Running Head: SARBANES-OXLEY ACT 1Document4 pagesRunning Head: SARBANES-OXLEY ACT 1twalkthis069No ratings yet

- Demand For Verified Evidence of "Trade or Business" Activity: Currency Transaction Report (CTR) InstructionsDocument19 pagesDemand For Verified Evidence of "Trade or Business" Activity: Currency Transaction Report (CTR) InstructionsShawn Psenicnik (ShawniP)No ratings yet

- United States v. Bramblett, 348 U.S. 503 (1955)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Bramblett, 348 U.S. 503 (1955)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eo 99111 22Document5 pagesEo 99111 22Kaylee SteinNo ratings yet

- Bill of Attainder-Ex Post Facto LawDocument4 pagesBill of Attainder-Ex Post Facto LawMeriem Grace RiveraNo ratings yet

- Bank Secrecy LawDocument6 pagesBank Secrecy LawAilaMarieB.QuintoNo ratings yet

- Estrada Vs SandiganbayanDocument198 pagesEstrada Vs Sandiganbayanangelica poNo ratings yet

- Counterfeit Securities DismissDocument24 pagesCounterfeit Securities DismissShane Christopher100% (3)

- People v. Rosenthal & OsmenaDocument3 pagesPeople v. Rosenthal & OsmenaBoy Omar Garangan DatudaculaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam-Paralegal WorkDocument4 pagesFinal Exam-Paralegal WorkPegalongan ESNo ratings yet

- Aris - Echavez DigestDocument18 pagesAris - Echavez DigestMykee AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction Chapter 5 SummaryDocument10 pagesStatutory Construction Chapter 5 SummaryBrian Balio100% (1)

- (DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - Quill - Letter #L8080 - Follow Up Letter On Interpretation of Willful - Version #2!02!15-2023 at 12-04 PMDocument8 pages(DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - Quill - Letter #L8080 - Follow Up Letter On Interpretation of Willful - Version #2!02!15-2023 at 12-04 PMHenry RodgersNo ratings yet

- DocStatutory Construction Case DigestDocument14 pagesDocStatutory Construction Case DigestDieanne MaeNo ratings yet

- Simple Treaty of ProtectionDocument8 pagesSimple Treaty of ProtectionJack MeHoffNo ratings yet

- Constructive Notice CADocument18 pagesConstructive Notice CAMike SmithNo ratings yet

- Civil ForfeitureDocument9 pagesCivil ForfeituresummermangoNo ratings yet

- 278 Scra 27Document1 page278 Scra 27Jun Rinon100% (1)

- Ligot Vs RepublicDocument5 pagesLigot Vs RepublicPaolo MendioroNo ratings yet

- 2001 Estrada - v. - Sandiganbayan20170221 898 Uz1rrp PDFDocument153 pages2001 Estrada - v. - Sandiganbayan20170221 898 Uz1rrp PDFMau AntallanNo ratings yet

- Republic V Eugenio Case DigestDocument4 pagesRepublic V Eugenio Case DigestFaye Allen Matas50% (2)

- United States v. Evans, 333 U.S. 483 (1948)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Evans, 333 U.S. 483 (1948)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Corpo DigestsDocument21 pagesCorpo DigestsJf ManejaNo ratings yet

- Engel v. O'MALLEY, 219 U.S. 128 (1911)Document5 pagesEngel v. O'MALLEY, 219 U.S. 128 (1911)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Civil Forfeiture Proceedings in The Philippines PDFDocument28 pagesCivil Forfeiture Proceedings in The Philippines PDFArjane Aram Samaniego100% (1)

- Ricarze Vs CADocument3 pagesRicarze Vs CACarl LawsonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008Document5 pagesG.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008hudor tunnelNo ratings yet

- AgPart 925 - TrustDocument130 pagesAgPart 925 - Trustcezar delailaniNo ratings yet

- STATCON CASE DIGEST 5 Nov. 24,2020Document36 pagesSTATCON CASE DIGEST 5 Nov. 24,2020credit analystNo ratings yet

- Estrada vs. Sandiganbayan'Document3 pagesEstrada vs. Sandiganbayan'Carla January OngNo ratings yet

- Sereno - Quo Warranto V ImpeachmentDocument3 pagesSereno - Quo Warranto V ImpeachmentJM PabustanNo ratings yet

- Impossible For The Judges Who Issued The Warrants To Have Found The Existence of Probable CauseDocument2 pagesImpossible For The Judges Who Issued The Warrants To Have Found The Existence of Probable CauselividNo ratings yet

- False Statements and Perjury: An Overview of Federal Criminal LawDocument24 pagesFalse Statements and Perjury: An Overview of Federal Criminal LawlllNo ratings yet

- Secrecy of Bank Deposits Law-NotesDocument5 pagesSecrecy of Bank Deposits Law-Notesjb_uy50% (2)

- University of The Philippines College of Law: Estrada V. SandiganbayanDocument6 pagesUniversity of The Philippines College of Law: Estrada V. SandiganbayanJelly BerryNo ratings yet

- Clovis Carl GREEN., JR., Petitioner, v. Honorable Edward W. NOTTINGHAM, District Judge Honorable Richard M. Borchers, Magistrate Judge, RespondentsDocument9 pagesClovis Carl GREEN., JR., Petitioner, v. Honorable Edward W. NOTTINGHAM, District Judge Honorable Richard M. Borchers, Magistrate Judge, RespondentsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Broward County - Notice of Claim and Claim of Damages-MAD-ArrestDocument12 pagesBroward County - Notice of Claim and Claim of Damages-MAD-ArrestHakeem100% (1)

- One Man Out Actual and Constructive NoticeDocument4 pagesOne Man Out Actual and Constructive NoticeRb100% (8)

- Churchill Vs TaftDocument10 pagesChurchill Vs TaftRhea Lyn MalapadNo ratings yet

- The Main Points of Difference Between The Bribery Act and The FPCADocument2 pagesThe Main Points of Difference Between The Bribery Act and The FPCAShobikaNo ratings yet

- Senate Bill 1056: Maryland Second Chance Act of 2014Document7 pagesSenate Bill 1056: Maryland Second Chance Act of 2014abc2newsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Bisceglia, 420 U.S. 141 (1975)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Bisceglia, 420 U.S. 141 (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Corporations-Officers and Directors-Liability For RepresentativeDocument9 pagesCorporations-Officers and Directors-Liability For Representativenirmalaradhakrishna18No ratings yet

- The Main Issue - IntegrityDocument12 pagesThe Main Issue - IntegrityNoreen T� ClaroNo ratings yet

- 42 Usc 1983Document15 pages42 Usc 1983CrystalmorganstudentNo ratings yet

- 2001 Estrada v. SandiganbahyanDocument154 pages2001 Estrada v. SandiganbahyanChristine Ang CaminadeNo ratings yet

- Bar Journal ArticleDocument10 pagesBar Journal ArticleD B Karron, PhDNo ratings yet

- Dealing With Federal Tax Liens Filed IllegallyDocument10 pagesDealing With Federal Tax Liens Filed IllegallyDonna Eubank Helm100% (1)

- (G.R. No. 94723) Case DigestDocument2 pages(G.R. No. 94723) Case Digestlawnotesnijan100% (4)

- ESTRADA vs. SandiganbayanDocument4 pagesESTRADA vs. SandiganbayanJoycee ArmilloNo ratings yet

- Constitution of the State of Minnesota — 1964 VersionFrom EverandConstitution of the State of Minnesota — 1964 VersionNo ratings yet

- Constitution of the State of Minnesota — 1960 VersionFrom EverandConstitution of the State of Minnesota — 1960 VersionNo ratings yet

- Cloud On TitleDocument1 pageCloud On Titleplaw15No ratings yet

- Lehman Brothers Lawsuit Trust BNC 3Document135 pagesLehman Brothers Lawsuit Trust BNC 3plaw15No ratings yet

- Breach of Fiduciary ResponsibilitiesDocument108 pagesBreach of Fiduciary Responsibilitiesplaw15100% (2)

- 3-11-09 Clerk Dorothy Brown Alerts ObamaDocument2 pages3-11-09 Clerk Dorothy Brown Alerts Obamaplaw15No ratings yet

- Mortgage-Mediation-Program-Factsheet 8 13 10Document2 pagesMortgage-Mediation-Program-Factsheet 8 13 10plaw15No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Control and AccountingDocument53 pagesChapter 4 - Control and AccountingLê Thái VyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Auditing and Assurance Services: Both Certified by 3 PartiesDocument13 pagesChapter 1 - Auditing and Assurance Services: Both Certified by 3 PartiescelineNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15Document4 pagesChapter 15helennguyen242004No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Business Its Legal Ethical and Global Environment 9th Edition JenningsDocument19 pagesTest Bank For Business Its Legal Ethical and Global Environment 9th Edition Jenningsa549795291No ratings yet

- Ais Chapter 7Document20 pagesAis Chapter 7CiaRa GinetaNo ratings yet

- (Control & AIS) Kelompok 2Document24 pages(Control & AIS) Kelompok 2AjiNo ratings yet

- Hyperion Financial ManagementDocument8 pagesHyperion Financial Managementsriuae1982No ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Multiple ChoiceDocument10 pagesCorporate Governance Multiple ChoiceAysha RiyaNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics ExamDocument7 pagesBusiness Ethics Exam明 志No ratings yet

- CISA Practice Questions To Prep For The Exam - TechTargetDocument9 pagesCISA Practice Questions To Prep For The Exam - TechTargetbirish2009No ratings yet

- 33 Yrs Audit Research FinalDocument133 pages33 Yrs Audit Research FinalRatna SaridewiNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 2Document4 pagesAssignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 2Haris MunirNo ratings yet

- Leadership Ethics and The Integrity Capacity ChallengeDocument38 pagesLeadership Ethics and The Integrity Capacity ChallengeJP De LeonNo ratings yet

- Powersc PDFDocument50 pagesPowersc PDFMauricio LocatelliNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument13 pagesAbstractKhooshal Yadhav RamphulNo ratings yet

- AWS Answers To Key Compliance QuestionsDocument12 pagesAWS Answers To Key Compliance Questionssparta21No ratings yet

- 25 - Evolution of Corporate Governance in India and AbroadDocument9 pages25 - Evolution of Corporate Governance in India and AbroadArunima SarkarNo ratings yet

- Accrual Based and Real Earnings Management Activities Around Seasoned Equity Offerings - 2010 - Journal of Accounting and Economics PDFDocument18 pagesAccrual Based and Real Earnings Management Activities Around Seasoned Equity Offerings - 2010 - Journal of Accounting and Economics PDFZhang PeilinNo ratings yet

- DOC-20240605-WA0012_Document21 pagesDOC-20240605-WA0012_Ayman AwadNo ratings yet

- A424: Chapter 6 Audit Responsibilities and Objectives Preparation QuestionsDocument8 pagesA424: Chapter 6 Audit Responsibilities and Objectives Preparation QuestionsNovah Mae Begaso SamarNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Part 1 Internal ControlDocument21 pagesModule 6 Part 1 Internal ControlKRISTINA CASSANDRA CUEVASNo ratings yet

- Related Party Transactions in Corporate Governance PDFDocument60 pagesRelated Party Transactions in Corporate Governance PDFfauziahNo ratings yet

- Question Text: Answer Saved Marked Out of 1.00Document10 pagesQuestion Text: Answer Saved Marked Out of 1.00angel diazNo ratings yet

- Juniper Networks Securities Fraud ComplaintDocument20 pagesJuniper Networks Securities Fraud ComplaintMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Financial Reporting and Analysis: AssignmentDocument4 pagesFinancial Reporting and Analysis: AssignmentXabi meerNo ratings yet

- Pe MCQSDocument53 pagesPe MCQSChris Rafel100% (2)