Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Passions of Learning in Tight Circumstances: Toward A Political Economy of The Mind (Annotated)

The Passions of Learning in Tight Circumstances: Toward A Political Economy of The Mind (Annotated)

Uploaded by

Zac ChaseCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Dokumen - Pub - The Dutch Overseas Empire 16001800 1108449514 9781108449519Document481 pagesDokumen - Pub - The Dutch Overseas Empire 16001800 1108449514 9781108449519dgjdf hgjhdgNo ratings yet

- Idea of Progress - Teodar ShaninDocument7 pagesIdea of Progress - Teodar ShaninNaveenNo ratings yet

- The Child and Postmodern SubjectivityDocument13 pagesThe Child and Postmodern SubjectivityDavid Kennedy100% (2)

- Review of Fear of Small Numbers by A. AppaduraiDocument4 pagesReview of Fear of Small Numbers by A. AppaduraiLaura Pearl KayaNo ratings yet

- Roy Porter, Marie Mulvey Roberts (Eds.) - Pleasure in The Eighteenth CenturyDocument288 pagesRoy Porter, Marie Mulvey Roberts (Eds.) - Pleasure in The Eighteenth CenturyEduardoBragaNo ratings yet

- Ball Curve WarDocument8 pagesBall Curve WarWinda OuroraNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Dystopia ThesisDocument9 pagesBrave New World Dystopia Thesismelissawardbaltimore100% (2)

- Individuality in Tess of The DurbervillesDocument9 pagesIndividuality in Tess of The DurbervillesDiganta BorgohainNo ratings yet

- Literature and Cultural Production: AllegedlyDocument16 pagesLiterature and Cultural Production: AllegedlyDavidNo ratings yet

- Kelompok 4: 1. How To Differentiate The Three Major Schools of Comparatists (The French, The American, The Russian) ?Document8 pagesKelompok 4: 1. How To Differentiate The Three Major Schools of Comparatists (The French, The American, The Russian) ?Ovi SowinaNo ratings yet

- Varene McDermott With CorrectionDocument23 pagesVarene McDermott With CorrectionjhosyleinNo ratings yet

- Los Usos de La LiteraturaDocument7 pagesLos Usos de La LiteraturaDavid LuqueNo ratings yet

- Past and Present: The Challenges of Modernity, from the Pre-Victorians to the PostmodernistsFrom EverandPast and Present: The Challenges of Modernity, from the Pre-Victorians to the PostmodernistsNo ratings yet

- Misbehavioral SciencesDocument7 pagesMisbehavioral SciencesLance GoNo ratings yet

- Zipes Tales XDocument4 pagesZipes Tales XCe OmmNo ratings yet

- Popular Culture, Hegemony, and Captain AmericaDocument3 pagesPopular Culture, Hegemony, and Captain AmericaFrankNo ratings yet

- The Age of MerchantsDocument246 pagesThe Age of Merchantssergio dezorziNo ratings yet

- Hard Times As A Dickensian DystopiaDocument9 pagesHard Times As A Dickensian DystopianaalumthendralNo ratings yet

- Marxist Literary Theory XDocument3 pagesMarxist Literary Theory XibantoyNo ratings yet

- Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and MoralsFrom EverandFolkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and MoralsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- S I: N E S I Writing The Erasure of Emotions in Dystopian Young Adult Fiction: Reading Lois Lowry's TheDocument16 pagesS I: N E S I Writing The Erasure of Emotions in Dystopian Young Adult Fiction: Reading Lois Lowry's TheAlif KharuddinNo ratings yet

- Politics and Teen FictionDocument6 pagesPolitics and Teen FictionJames WatsonNo ratings yet

- Fear Definition EssayDocument8 pagesFear Definition Essayvdyvfjnbf100% (2)

- Edward Said Culture and ImperialismDocument6 pagesEdward Said Culture and ImperialismmairaNo ratings yet

- By Dermot Quinn: Almanac To Keynes's General Theory. Another Problem Is That They Have PowerDocument5 pagesBy Dermot Quinn: Almanac To Keynes's General Theory. Another Problem Is That They Have PowerJune KimNo ratings yet

- Disablity in Prose FictionDocument16 pagesDisablity in Prose Fictionall4bodee100% (1)

- Bianco 15: Bracketed For Gendered LanguageDocument14 pagesBianco 15: Bracketed For Gendered LanguageJillian LilasNo ratings yet

- Karl Stern Flight From WomanDocument7 pagesKarl Stern Flight From WomanSarban Malhans0% (1)

- (Download PDF) Microeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2Nd Edition Thomas Nechyba Full Chapter PDFDocument22 pages(Download PDF) Microeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2Nd Edition Thomas Nechyba Full Chapter PDFnanieyeusope100% (9)

- Module Iii Books That Changed HistoryDocument16 pagesModule Iii Books That Changed HistoryLian Erica LaigoNo ratings yet

- FeedpaperDocument8 pagesFeedpaperapi-276665265No ratings yet

- T W E: M R M T: Introduction: Establishing The Ground of ContestationDocument22 pagesT W E: M R M T: Introduction: Establishing The Ground of ContestationKhalese woodNo ratings yet

- Oxford University PressDocument4 pagesOxford University PressNikos KalampalikisNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document7 pagesArticle 2Lala LandNo ratings yet

- AP Lang Q3 Argumentation Question 3 From Past ExamsDocument4 pagesAP Lang Q3 Argumentation Question 3 From Past ExamsSarah ShierNo ratings yet

- Eng PG-II CC-9 (Hard Times) DR Ravi K SinhaDocument4 pagesEng PG-II CC-9 (Hard Times) DR Ravi K Sinhajhjh32812No ratings yet

- Edward Said IntellectualsDocument4 pagesEdward Said Intellectualsmuhsain khanNo ratings yet

- THE HOUSE OF INTELLECT - J. BarzunDocument500 pagesTHE HOUSE OF INTELLECT - J. BarzunIntuição Radical0% (1)

- Mendelssohn - What Is Enlightenment?Document5 pagesMendelssohn - What Is Enlightenment?Giordano BrunoNo ratings yet

- The School Story: Young Adult Narratives in the Age of NeoliberalismFrom EverandThe School Story: Young Adult Narratives in the Age of NeoliberalismNo ratings yet

- Disability in Fairy Tales 2Document19 pagesDisability in Fairy Tales 2JesusMNo ratings yet

- Gned10 3rdimDocument24 pagesGned10 3rdimMaria Genica ColinaNo ratings yet

- A Level Mediastudies KeytermsDocument18 pagesA Level Mediastudies KeytermsFilozotaNo ratings yet

- Distopia Work PDFDocument33 pagesDistopia Work PDFÂnderson MartinsNo ratings yet

- A Critical Review of Benedict AndersonDocument7 pagesA Critical Review of Benedict AndersonMatt Cromwell100% (10)

- Readings - Social Sciences 129 PPDocument127 pagesReadings - Social Sciences 129 PPNigel IsaacNo ratings yet

- Politics and Teen FictionDocument5 pagesPolitics and Teen FictionJames WatsonNo ratings yet

- Perils of Protection: Shipwrecks, Orphans, and Children's RightsFrom EverandPerils of Protection: Shipwrecks, Orphans, and Children's RightsNo ratings yet

- +rebellion and Mental IllnessDocument63 pages+rebellion and Mental IllnessMaríaNo ratings yet

- Essay On Independence DayDocument5 pagesEssay On Independence Dayd3gxt9qh100% (2)

- IdentityDocument6 pagesIdentityChristina HernandezNo ratings yet

- Advice From Harvard: 10 Skills For Success in The Global EconomyDocument4 pagesAdvice From Harvard: 10 Skills For Success in The Global EconomyAlonso Muñoz PérezNo ratings yet

- Inglis Review by Blake Seidenshaw-2Document3 pagesInglis Review by Blake Seidenshaw-2Robert BranchNo ratings yet

- Essay On The IliadDocument6 pagesEssay On The Iliadheffydnbf100% (2)

- Underlying Themes in The Witchcraft of Seventeenthcentury New en 1970Document16 pagesUnderlying Themes in The Witchcraft of Seventeenthcentury New en 1970Rayane DouradoNo ratings yet

- Ortner - Generation X PDFDocument27 pagesOrtner - Generation X PDFataripNo ratings yet

- Critical Tradition and Ideological Positioning (Sarland)Document4 pagesCritical Tradition and Ideological Positioning (Sarland)viviana losaNo ratings yet

- The Racial Dimensions of Social Capital: Toward A New Understanding of Youth Empowerment and Community Organizing in America's Urban Core A. A. AkomDocument23 pagesThe Racial Dimensions of Social Capital: Toward A New Understanding of Youth Empowerment and Community Organizing in America's Urban Core A. A. AkomUrbanYouthJustice100% (1)

- Plea For Truthful Analysis of Ongoing EventsDocument3 pagesPlea For Truthful Analysis of Ongoing EventszizekNo ratings yet

- When They Read What We WriteDocument30 pagesWhen They Read What We WriteRodrgo GraçaNo ratings yet

- Izanagi Philosophical Views in Buying BehaviorDocument6 pagesIzanagi Philosophical Views in Buying BehaviorRegie BayaniNo ratings yet

- Fable of The Bees Mandeville PDFDocument2 pagesFable of The Bees Mandeville PDFChrisNo ratings yet

- Allegories of Farming From Greece and Rome Philosophical Satire in Xenophon, Varro, and Virgil PDFDocument236 pagesAllegories of Farming From Greece and Rome Philosophical Satire in Xenophon, Varro, and Virgil PDFSotirios Fotios Drokalos100% (1)

- Vries - The Industrial Revolution and The Industrious RevolutionDocument22 pagesVries - The Industrial Revolution and The Industrious Revolutionanton.de.rotaNo ratings yet

- Norman Barry, The Tradition of Spontaneous Order: A Bibliographical EssayDocument7 pagesNorman Barry, The Tradition of Spontaneous Order: A Bibliographical EssayAnonymous ORqO5yNo ratings yet

- Mandeville - Fable of The BeesDocument40 pagesMandeville - Fable of The Beesmpq91100% (1)

- Mandeville - ''The Fable of The Bees''Document410 pagesMandeville - ''The Fable of The Bees''Ivan SzytiukNo ratings yet

- Thomas A. Horne (Auth.) - The Social Thought of Bernard Mandeville - Virtue and Commerce in Early Eighteenth-Century England-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1978)Document134 pagesThomas A. Horne (Auth.) - The Social Thought of Bernard Mandeville - Virtue and Commerce in Early Eighteenth-Century England-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1978)包天誉No ratings yet

- Trancripts MOOC Classical Sociological TheoryDocument97 pagesTrancripts MOOC Classical Sociological TheoryHigoNo ratings yet

- In Conversation With Andre Beteille PDFDocument63 pagesIn Conversation With Andre Beteille PDFAnkur RaiNo ratings yet

- 2-Mandeville - Fable of The Bees PDFDocument45 pages2-Mandeville - Fable of The Bees PDFJorge RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Joseph Andrews Lecture 1Document7 pagesJoseph Andrews Lecture 1khushnood aliNo ratings yet

- Greed: Julian Edney, PHDDocument35 pagesGreed: Julian Edney, PHDJose G. VelezNo ratings yet

- The Industrial Revolution and The Industrious RevolutionDocument23 pagesThe Industrial Revolution and The Industrious RevolutionSimonaEsterMelisNo ratings yet

- 7 KAYE F.B. - The Writings of BMDocument50 pages7 KAYE F.B. - The Writings of BMlabm00911No ratings yet

- Lenguaje Politico Modern EUR Polemica ESP Indias Pagden PDFDocument374 pagesLenguaje Politico Modern EUR Polemica ESP Indias Pagden PDFAlberto NavasNo ratings yet

- Jesse DuplantisDocument10 pagesJesse DuplantisTimothyNo ratings yet

- Mandeville Early WorksDocument450 pagesMandeville Early WorksGuy DeboringNo ratings yet

- Pub - The English Novel in History 1700 1780 The Novel I PDFDocument290 pagesPub - The English Novel in History 1700 1780 The Novel I PDFMaida Khan100% (1)

- English Literature - The 18th Century - Britannica - Com - ANTONIO RESTANODocument25 pagesEnglish Literature - The 18th Century - Britannica - Com - ANTONIO RESTANODaniela SilvaNo ratings yet

- Self Love Egoism and The Selfish Hypothesis Key Debates From Eighteenth Century British Moral Philosophy 1st Edition Christian MaurerDocument70 pagesSelf Love Egoism and The Selfish Hypothesis Key Debates From Eighteenth Century British Moral Philosophy 1st Edition Christian Maurerlburiceclbm100% (4)

- CIA EthicsDocument76 pagesCIA EthicsGuy FalkNo ratings yet

- (1670 - 1733) Bernard Mandeville - The Fable of The BeesDocument3 pages(1670 - 1733) Bernard Mandeville - The Fable of The BeesdrpedrofNo ratings yet

- The Oldest ProfessionDocument7 pagesThe Oldest ProfessionEniko BodisNo ratings yet

- The Three Piece Suit and Modern MasculinityDocument7 pagesThe Three Piece Suit and Modern MasculinityYangyang MaoNo ratings yet

- Unveiling Fashion Business, Culture, and Identity in The Most Glamorous Industry by Frédéric Godart (Auth.)Document223 pagesUnveiling Fashion Business, Culture, and Identity in The Most Glamorous Industry by Frédéric Godart (Auth.)Daniela Arroyo100% (2)

- History ConsumerismDocument5 pagesHistory ConsumerismAna Popescu100% (1)

The Passions of Learning in Tight Circumstances: Toward A Political Economy of The Mind (Annotated)

The Passions of Learning in Tight Circumstances: Toward A Political Economy of The Mind (Annotated)

Uploaded by

Zac ChaseOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Passions of Learning in Tight Circumstances: Toward A Political Economy of The Mind (Annotated)

The Passions of Learning in Tight Circumstances: Toward A Political Economy of The Mind (Annotated)

Uploaded by

Zac ChaseCopyright:

Available Formats

The Passions of Learning in Tight Circumstances: Toward a Political Economy of the Mind

RAY MCDERMOTT Stanford University

Economies make their demands, and by necessity, people adjust, learn, and survive. People adjust to tight circumstances with passion and ingenuity. Necessity and its passions are the stuff of reality and generally more than schools or educational research can handle. Mainstream theories of learning have captured economic constraints only statistically and symptomatically (as if being short on money means being short on ingenuity). A focus on the demands of necessity promises a more grounded view of educational possibilities.1 It can deliver portraits of what people in trouble can do, rather than what they cannot do, and it promises research better tuned to the work of democracy. To illustrate the case, I invoke the power of novels to capture both the press of circumstance and the ingenuity of people facing difficulties. I do so in five sections: one on why novels are attentive to economic necessity; a second on political economies as learning environments; and three sections on the passions of necessity in three novels that stretch the usual borders of research on learning. I am not asking learning researchers to write novelsDeus avertat!but to reduce the limitations of educational research by modeling the success of fiction at imitating and expanding reality. Careful empirical studies of learning can profit from the attention of novelists to the nuances of necessity.2

National Society for the Study of Education, Volume 109, Issue 1, pp. 144159 Copyright by National Society for the Study of Education, Columbia University

Political Economy of the Mind 145

THE QUESTION How do novelists develop enriching portraits of people at the bottom end of social structurethe poor, the hungry, the tired, and far too many of them women and childrenwhile so much social science, psychology, and educational research answers to the description of what is wrong with them? For one answer, consider that educational research relies on narrow streams of evidence, but novelists portray potentially whole persons with thick lives. Fictional accounts of economic matters are peripheral to institutionalized educational research that speaks from inside current categories, to current conditions as the only possible reality, and in terms of received measures of evaluation. Freed of a duplicitous commitment to things as they are, fiction can tell us more about what we should appreciate and emulate. Whether in fiction or reality, the more known about characters, the more they make sense. Fictional and empirical make a forced contrast set. The terms are better pairedand paredby their common enemy: work that hinders imagination and distorts the innermost powers and virtues of those it describes. Characters in great novels are more than just flawed or maimed, but flawed or maimed in relation to others, in circumstances engaged and manipulated by others, and precisely so, one page of detail after another. Every account of either growth or decline must be delivered as if in the flesh. If novelists are to capture an audience, they must develop characters from multiple points of view; detail, locale, direction, tension, neurosis, and struggle make good reading. Characters must interact, sleep, fight, and get interpreted with each otherenmeshed, embedded, embroiled, and embellishedand every step is complex with passion and ingenuity. Even in novels that focus on a single person (Crime and Punishment) or that take place across a single day (Ulysses) or in a single setting (Tristram Shandy)even in novels focused on persons defined by the negation of others (Watt)characters must be situated deeply (from their senses into their selves), widely (from their senses out to others), and hierarchically (from their senses hammered by conditions not of their own making). Every voice must be tuned to the received circumstances, coordinated agendas, and overlapping imaginations that feed the passions and give occasion to learning.3 In a preface to his early novel, Oliver Twist, itself a response to the draconian Poor Laws of 1834, Charles Dickens (18121870) set perhaps the first rule for practice-driven theory in a society that promises equality but delivers a population divided by class, race, gender, or other arbitrary markers and makers of unjust hierarchy. Dickens demanded that novels

146 National Society for the Study of Education

display the disenfranchised both caught in miserable reality and guided by the principle of Good surviving through adverse circumstance, and triumphing at last (1841/1993, p. 3). As if he were no less than an ethnographer with a rich imagination, Dickens portrayed injustice in what people undergo and celebrates what they accomplish against the odds. In comparison, educational research stresses the deprivations of poverty, forgets to celebrate what people can do, and avoids confronting those who create, measure, and profit from the problems. Dickens heads a long list of novelists who have known better than deprivation theorists. He highlighted the Good, but he delivered equally on fluency, intelligence, competence, curiosity, and learning. So did Daniel Defoe (16601731) and Zora Neale Hurston (18911960). A century before Dickens, Defoe wrote a preface for Colonel Jack, his novel about an adolescent pickpocket who turned into a calculating and sometimes successful merchant: Though circumstances formd him by Necessity to be a Thief, a strange Rectitude of Principles remaind with him, and made him early abhor the worst Part of his Trade (1722/1989, p. 1). Young Jack did what he had to and learned along the way. A century after Dickens, in Their Eyes Are Watching God, Hurston delivered people silenced by their situation until they migrated to a rough and tumble new place of possibility. Educational researchers might share Hurstons initial account of people ugly from ignorance and broken from being poor (1937/1990, p. 125), butthe world being easier to change in fiction than in realitythey rarely portray the same people transformed in more productive conditions. Educational policy usually ends where it begins: wallowing in intractable problems. Like Defoe and Dickens, Hurston instead delivered people transformed in new settings, people who find out about livin fuh theyselves (p. 187): Blues made and used right on the spot. Dancing, fighting, singing, crying, laughing, winning and losing love every hour. Work all day for money, fight all night for love (p. 125). What happened to their cultural deprivation, their at-risk developmental traits, their impaired cognitive growth? What happened to their limited knowledge, vocabulary, work skills, or motivations? Under new conditions, those previously thought to be unable became, in these novelists accounts, suddenly able. POLITICAL ECONOMIES OF LEARNING The first fact, not enough attended in education, is that economic conditions organize what has to be learned. The claim invites little argument

Political Economy of the Mind 147

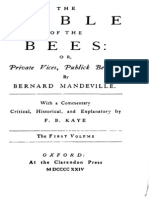

capitalists and socialists agreebut educational research inscribes mostly the symptoms and hides the loaded systems of reward and benefit that create and legitimate the results. Schools develop a limited version of the knowledge needed in life. The greater learning is organized and made consequential in tune with economic necessities. Three data points over 200 years can only suggest a pattern of novels trumping learning research for an appreciation of those caught in whatever version of the Achievement Gap that was once current. The three economiesDefoe in early-18th-century merchant capitalism, Dickens in mid-19th-century industrial capitalism, and Hurston in post-Depression 20th-century welfare capitalismare different enough to allow a minimal outline of how learning is coordinated with the demands of survival.4 Passions are central to a political economy of minds in action. Dickens recommended them to economists: Political economy is a mere skeleton unless it has a little human covering and filling out, a little human bloom upon it, and a little human warmth in it (1854/1990b, p. 296). All novels can be read for the economic conditions they assume, represent, or reveal in their displays of human bloom and warmth.5 Some novelists have dealt directly with political economy in their fiction (Honor de Balzac with money dealings every few pages in Pere Goriot). A few have written their own economics (Defoe, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and the poet Ezra Pound), and at least one (Andr Gide) shared the task with an uncle (Charles Gide, the economist). Of our three, Defoe staged money struggles throughout his novels and advice books, Dickens less so, and Hurston only occasionally, but none of their characters makes sense outside the prevailing political economy. The second fact is more specific to ideologies of learning. How learning is conceived, taught, assessed, and used to position people in society fits not just economic conditions, but the economic theories developed at the same time. Ideas about production, consumption, and exchange, about profit, capital, and investment, and about survival, greed, and responsibility all circumscribe concerns for and consequences of learning. Defoe can be readroughly, suggestivelywith Bernard Mandeville (1732/1924), Dickens with Karl Marx (1859/1982), and Hurston with John Maynard Keynes (1936/1997).6 Labor does not unilaterally determine the ideas guiding earning and learning; rather, ideas about the workings of money and the play of minds are developed from the same social predicaments and conceptual materials.7 In situations real and imagined, novelists and economists have portrayed peoples predicaments and concepts with a thickness that has kept the necessity and passions of learning in full view.

148 National Society for the Study of Education

THE NECESSITY OF LEARNING IN DEFOE (AND MANDEVILLE) All Defoe characters are put upon by difficult circumstances. Survival is their issue. Defoe did not create individuals with deeply divided motives (Birdsall, 1985; Roberts, 1990; Dickens found Defoe without emotion). Depth psychology is hardly necessary in a one-up/one-down, have/have not world. Reality has limited their choices.8 Moll Flanders has to stay out of the poorhouse, Col. Jack has to stay out of jail, and Robinson Crusoe has to create a social world from remnants. When necessity calls, conscience and style are extras and figure only enough to make Moll, Jack, and Crusoe attractive rascals. We love them because they adjust adroitly to how the world unfolds, not because they transform society. The world around them was unfolding wildly: Capitalism was on the rise, and most things were getting a price tag. Greed was redefined: from an occasion of sin to a virtue (Dean, 1991; Hirschman, 1997; Webb, 1981). Individuals were commodified, even intellectuals: Genius was changing from a medium of inspiration to a kind of person (McDermott, 2004), and creative work was shifting from a contribution to a copyrighted possession (Woodmansee, 1984). Most of Defoes characters turned to the high seas to escape charges or to venture high-stakes commerce. Colonialism was central to the emerging world, but Col. Jacks list of productsconsumer extras, really shipped from Virginia confirms that the English economy was still local (1722/1989). Success was personal. Double-entry account booksfor Max Weber (1904/1998) the site of rational planning for costs and profitswas, for Defoe, more a way to look good. He warned that a shopkeeper who does not keep an exact account of what goes out and comes in, can never swear to his books, or prove his debts, if occasion calls for it (1726/1987, p. 188). Occasion always called for accounts in merchant capitalism. Defoes characters were rarely more than their next business partner, spouse, lover, or lender could afford. The economy was at hand. Failure threatened. Everyone was replaceable. Learning was always necessary. Defoe shows how Jack is acquired by the system. A street waif, he begs for food by day and sleeps over a glassworks at night. Recruited by pickpockets, he gets more fully appropriated by the money economy. When he obtains a fist full of money, he is baffled and loses sleep until he buys pants with pockets. In a stunning passage, he joins passion and learning to the work of getting enough money to buy what is needed to meet the demands of money. This was enough to let anyone see how all the Sorrows and

Political Economy of the Mind 149

Anxieties of Mens Lives come about, how they rise from their restless pushing at getting Money, and the restless Cares of keeping it once they have got it . . . I knew not what Money was, or what to do with it; and never knew what it was not to sleep, till I had Money to keep, and was afraid of losing it. (1722/1989, p. 40) Jack was acquired by a money system that defined his needs, deeds (of both kinds), and misdeeds (of many kinds). Narrow escapes and occasional success followed.9 Moll says, moneys virtue, gold is fate (Defoe, 1722/1996, p. 72). About the time Defoes characters were learning the new marketplace, Bernard Mandeville (16701733) was building theory for a dog-eat-dog merchant economy.10 In a 1705 poem and then in theoretical tirades until he died, Mandeville compared human society to a Grumbling Hive: Fraud, Luxury and Pride must live, While we the benefits receive: Hungers a dreadful Plague, no doubt, Yet who digests or thrives without? (1732/1924, p. 36) Societies driven by aggressive self-concern, not virtue, are efficient and productive. Bees would not waste their time being good, making believe they were good, or telling others how to be good. Bees work and get others to work. Charity is a waste. The poor are more unwilling than unable. In Defoes novels, he was sensitive to the plight of the poor, but in policy pamphlets, he sounded like Mandeville: Down with charity! Up with Poor Laws! (Defoe, 1704/2004; also Dean, 1991). Policy is more abstract and distant from reality than fiction. For Mandeville and Defoe, there is always work to be done, and the poorthe worker beesshould do it: There is no Intrinsick Worth in money but what is alterable with the Times, and whether a Guinea goes for Twenty Pounds or for a Shilling, it is . . . the Labor of the Poor, and not the high and low value that is set on Gold or Silver, which all the Comforts of Life must arise from . . . we have hardly Poor enough to do what is necessary to make us subsist. (Mandeville, 1732/1924, pp. 301302) The poor work because they have to survive. Mandeville (1924) echoes Defoe on the primacy of economic necessity: If no body did Want no body would work (287).

150 National Society for the Study of Education

For Defoe and Mandeville, what counts is what can be counted: on both sides of exchanges unmediated by undue concern for others. The rule of gold trumps the golden rule. Real learning happens while doing what has to be done. Book learning is valued, said Defoe, if it affords control over ones situation (but not for the poor, said Mandeville11). Ideas about survival and greed circumscribe learning and its consequences. Its pockets all the way down. THE DEGRADATION OF LEARNING IN DICKENS (AND MARX) In Hard Times, Dickens (1854/1990a) opens with a tortured classroom where students are crammed with gallons of facts poured into them by Mr. Gradgrind and Mr. MChoakumchild. No fantasy is allowed, nor any real knowledge. A definition of a horse requires species specifics from the dictionary, and the child who knows real horses from work at the circus is taunted for her ignorance of dictionary facts. Learning is all abstractions on sale for a particular kind of economy: laissez-faire in the service of those who fit closest to dictionary definitions. The economy is hard on everyone in Coketown. School learning only delays ruin. The opposition of school and real learning at one level gives way to connections between them at another. Dickens identifies his audience, not the one he aims to please, but the one he confronts: utilitarian economists, skeletons of schoolmasters, Commissioners of Fact, genteel and used-up infidels, gabblers of many little dogs-eared creeds (Dickens, 1854/1990a, p. 123). He tells them to take care of their poor: Before they and their bare existence stand face to face, Reality will take a wolfish turn, and make an end of you (123). Concern for the poor was high fashion (Tobin, 1995), and behind it was a reaction to the rampant competitiveness of the economy. Dickens lampoons the latter with a man who apologizes for giving his own mother, already in a poorhouse, a halfpound of tea a year, when his proper duty was to self-interest: His only reasonable transaction in that commodity would have been to buy it for as little as he could possibly give, and sell it for as much as he could possibly get; it having been clearly ascertained by philosophers that in this is comprised the whole duty of mannot a part of mans duty, but the whole. (89) It not only pays to be calculating, it is a moral requirement. So preaches Gradgrind to his students. By the end of the book, Dickens has reversed the situation: Gradgrind has been made painfully aware of his foolish stand, circus girl has grown into a decent person, and dictionary master

Political Economy of the Mind 151

pupil has become the decision-maker on Gradgrinds son going to prison. Dictionary boy sticks to his early education: The whole system is a question of self-interest. What you must always appeal to, is a persons self-interest. Its your only hold. We are so constituted. I was brought up to that catechism when I was very young, Sir, as you are aware (211). Gradgrind offers a bribe. After rational calculations, it is rejected. Most Dickens characters are put upon by relentless troubles. Their social structure is deadening. We pity them because of the narrow range of possibilities they face. Learning comes to them as corrections too late to be of help. The world around them had been changing quickly: Capitalism had become dominant, and just about everyone, every fact, and every emotion had a price tag.12 Virtue had shifted to greed for owners and subservience for workers, and any lack of success was easily explained as a personal fault. Individuals were more thoroughly commodified than for Defoe. Even mothers had become only objects (worth less than a half pound of tea a year). Intellectuals too: Genius had been turned into a biological inheritance, and creative work increasingly required an antisocial heroism. Karl Marx (18181883) was responding to the same economy that stimulated harsh portraits by Dickens. They were reading the same government reports and agreed on what an economy should not be. Access, prestige, adaptability, and power had to be articulated through capital (for Marx, capital is property taken from the labor of others). What then of learning? Here is Marxs description of the problem: If we may take an example from outside the sphere of material production, a schoolmaster is a productive worker when, in addition to belaboring the heads of his pupils, he works himself into the ground to enrich the owner of the school. That the latter has laid out his capital in a teaching factory instead of a sausage factory, makes no difference to the relation. (1867/1976, p. 677) Gradgrinds school belabored the heads of children with facts of no relevance, but for the price they might bring on the market. Learning was on sale, and so it was conceived, taught, assessed, and used to position people in society. Most everybody gets stuffed. Dickens on people can sound like Marx on economy: The capitalist there, who had made sixty thousand pounds out of sixpence, always professed to wonder why the sixty thousand nearest Hands didnt each make sixty thousand pounds out of sixpence, and more or less reproached them every one for not

152 National Society for the Study of Education

accomplishing the little feat. What I did you can do. Why dont you go and do it? (Dickens, 1854/1990a, p. 90) Learning was fitted not just to industrial capitalism, but to its economic theories (Lave & McDermott, 2002). Its sausages all the way down. INVESTMENT AND LEARNING IN HURSTON (AND KEYNES) In Their Eyes Are Watching God, the passions of learning are tied to the passions of Janies relationship with three men, in sequence, across decades. Each relationship exists in a different economy (or more accurately, in three different situations inside early welfare capitalism). Janie is tied to her first husband by her grandmother, who thought that a put-upon man doing put-upon work on his own sixty acres could ensure survival. The second husband promises relief and prosperity and makes good by becoming land baron, general store owner, and mayor of a small African American town. Janie runs the store and serves her dominating husband. New kinds of learning become possible, but against a more invidious range of constraints. With a focus on money and power, Mayor Joe is equally tuned to what others do not, cannot, and should not do; he keeps Janie quiet and on guard for mistakes he is anxious to find. She particularly hates the mathematical dilemma that comes with running a store: Maybe cheese was thirty-seven cents a pound and somebody came and asked for a dimes worth. She went through many silent rebellions over things like that. Such a waste of life and time. But Joe kept saying that she could do it if she wanted to and he wanted her to use her privileges. That was the rock she was battered against. (Hurston, 1937/1990, p. 51) Janie was the mayors high-status wife with an expanding bank account, but at the price of losing her self, her tongue, and her learning. When the mayor dies, Janie sent her face to his funeral, and herself went rollicking with the springtime across her world (pp. 8485). The third man, Tea Cake, brings her to a high-risk/reward economy in the Everglades where Janie experiences life with more delightful emotions, more productive emergencies, and new learning tasks. She leaves behind the general store and much of her money for the promise of Tea Cake and the swamp. Tea Cake is a leader, a gambler, and a relentless lover of Janie. Hard work is necessary, risk everywhere; and so too learning: necessary and everywhere. Problems come up, problems get

Political Economy of the Mind 153

solvedor not. Either way, there is much to be achieved, much to be learned. With the mayor, life was a mix of profit and repression; with Tea Cake, life is a match of problem-solving, risk, suffering, and gleeful success. Together they find out about livin fuh theyselves (p. 187). Michael Tratner (2001) has tied Hurstons novel to the economics of John Maynard Keynes (18831946). Their Eyes and Keyness (1936/1997) General Theory were published only one year apart, and both in the midst of the Depression, but two projects could not be less alike in appearance. Keynes was trying to save capitalism by discovering the basic logic of the system and applying it to national policies. His goal was nothing less than relieving countries, particularly their unemployed, from boom and bust cycles and establishing the more stable and dynamic economies essential for democracy (fortunately, Roosevelt was listening). Janie, on the other hand, was trying to find a balance between love and security in a broken economy, in a harsh environment, and in a gender- and race-divided country with most of the population rooting in principle for her failure. Tratner takes the key terms of their shared project to be demand and investment. From its earliest speculations, economics had been focused on production, then consumption: so much in and so much out. For Keynes, the system was more delicate, and the ins and outs of production and consumption, or costs and profits, were tied to the ups and downs of the overall system. He called attention to the marginal efficiency of capital, which he definednovel readers bewareas being equal to that rate of discount which would make the present value of the series of annuities given by the returns expected from the capital-asset during its life just equal to its supply price13 (p. 135). This is more than a double-entry account book can handle. Complexity is the point. The system has grown too entangled for a laissez-faire rationale. Bottomed-out can stay bottomed-out without a careful program of intervention. Good policy can stimulate the twin powers of capitalism effective demand and the sufficiency of the inducement to invest (Keynes, 1936/1997, p. 358). Neither Hurston nor her Janie was reading Keynes, but they were each dealing with related problems in related ways. The world around them was unfolding for the worse: Capitalism was on the decline, and things had price tags few could afford. Greed was repressed in the terrible sense that investment had disappeared. High risk and unemployment were not just possible everywhere; they were systematically everywhere. With her first husband/economy, Janie had no voice, no love, no learning, no profit, and no self-calculated risk. With her second husband/economy, Janie had no voice, no love, little learning, and profits with savings, but no self-calculated risk. With Tea Cake, she takes risks, makes investments,

154 National Society for the Study of Education

and gains voice, love, and learning (Gates, 1990). Every day brought a new desire, a new awareness, a new skill, and, sometimes, a new gain. Far from the saddening crowd, from the mainstream economy, from White people, from unnecessary constraint, from pent-up desire, Janie (with and without Tea Cake), with a bank account and insurance policy at her back, found a new way to join effective demand and an inducement to invest in the fields, in conversations, in card games, and in the bedroom. Its the best played plans all the way down. CONCLUSIONS Take it that the world is a system of signs. Individual minds, like commodities, are a fast action nexus for signs being recognized, combined, adjusted, and directed to particular ends. Schools monitor the minds, stock markets monitor the commodities, and, together, the SAT, Nasdaq, GPA, Dow Jones, and NAEP keep tabs on their intercourse. Research on labor and learning lives in, lives on, and lives out the material and symbolic resources that organize signs into systematic and consequential patterns. Sub-rosa tight ties between economic theories and arbitrary measures of knowledge have helped commodify and alienate learning to the point that fiction has become an essential alternative to educational research. If test scores record the lucre of the mind, fiction attests to the lives that resist crude simplifications. The wonders of learning in the face of necessity suggest alternatives to the deadening definitions of learning that currently dominate schools and their often discounted public. Inquiries into productive lives in other times and places, delivered through various genres, consistently offer portraits of complex adaptations and learning by everyone from inside the particulars of their situation. Trying to change lives from inside a persons head while systematically ignoring his or her circumstancesthe same circumstances that educators help to build and that evaluators use to define and display their expertiseseems a defeating call to arms and harms. Where novels deliver life, schools deliver life for only the seeming best and a disappreciation for the rest. The very coinage of the brain that Shakespeare used as a metaphor for imagination (Hamlet III.4.143; and Dante, Purgatorio, XVII, 32) has become the ideological and bureaucratic center of educational policy and assessment. The very coinage of the brain turns out to be exactly that: money itself intertwined with intellectual coinage, or degrees, hard pressed in schools and inscribed with aptitude measures and test scores. Like money, displays of knowledge get unevenly distributed through society. The mainstream image of learning is overly commodified. Once a term

Political Economy of the Mind 155

for the progress people make with problems over time, learning has been abstracted to death, quantified, and put up for sale. The overlap between what and how we learn and what we call learning has grown small. Everyone is learning all the time, but most of it goes unacknowledged, unaccounted, and unexplained by learning specialists. What counts, and accounted, is a particular kind of learning, not just the kind that comes from books or shows up in school, but the specific kind that gets measured by tests, norm-referenced tests with little articulation to contexts, purposes, kinds of learners, and consequences. Global norming reigns and with little accountability. Validity, Hurston might have said, is the kind of rock we have arranged to batter our heads against. Paolo Virno (2008) complained that money is a dizzying abstraction, compared to which the theorems of symbolic logic seem do-it-yourself stuff. With money you can buy any consumer goods you like (p. 42) (or Marx, 1867/1976). He could have included learning and educational degrees. As the ultimate commodity, money makes abstractions real and turns the real objects it can be exchanged for into ideas or desires; as a new commodityrhetorically pivotal in an information-paced society test scores turn aptitudes and grades into realities and turn real learning into something distant, incalculable, and perhaps invisible.14 School turns real learning into mere do it yourself stuff, so available, so right under your nose, that it is hidden from view by your own activities. For every old currency, there is a numismatics. A currency makes everything, in varying proportions, equivalent to everything else. Numismatists restore life to old currencies by recovering their functions in the contexts of their time. Their job, said Virno (2008), is to recover the activities that once brought a currency to power. Educational researchers must do the same for learning. Researchers must make concrete, that is to say sensual and temporal, all that is constrained by todays dominant real abstractions (p. 44). Test scores have become a dominant real abstraction: dominant in the institutional discourse of schools, real in consequences far beyond what should be claimed for them, and an abstraction in the sense of ripped from its relations to ongoing events. Test scores have become the false coins of the realm. There is good news. When educational researchers struggle empirically to recover the sensual and temporal lives of learners, they can turn to novelists for artfully crafted guidance on the partial, but always in full play, wisdom of the people involved. Novelists have generally shown the poor to be virtuous, articulate, smart, skilled, open, and informed in proportions organized more by moment than by fixed traits. They reveal what William James (1902/1982) called the individual pinch of destiny . . . where we catch real fact in the making (pp. 429, 431).15 Mainstream

156 National Society for the Study of Education

educational research has made things worse by focusing on the symptoms of the systemindividual kids, parents, teachersinstead of challenging those on the make and take with the lives of the left out and left behind. Acknowledgments

Brian Edgar, Alicia Grunow, Bronwen LaMay, Kathleen OConnor, and Daniel Steinbock helped shape these ideas with me. Eric Bredo, Elliot Eisner, Shelley Goldman, and Roy Pea helped constrain a text trying to say everything at once. Richard Blot directed me to Raymond Williams on Hard Times.

Notes

1. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1754/1984) on the passions underlying human understanding: It is by the activity of the passions that our reason improves itself; we seek to know only because we desire to enjoy; and it is impossible to conceive a man who had neither desires nor fears giving him the trouble of reasoning (p. 88). And one page later, on necessity: It is impossible to conceive how any man acting by his own faculties alone, and without the help of communication or the stimulus of necessity, could bridge so great a gulf as that between pure sensation and the simplest knowledge (p. 90, italics added). 2. Ties between science and literature are multiple and various. Empirical studies by linguists and ethnographers can surpass novels for fine detail set roughly in the context of economic pressures (for an example from educational settings, see Rampton, 2007). In the other direction, the last generation of cultural anthropologists has paid more attention to riches of fiction (perhaps nothing better than Plath, 1980). Literary critic Hugh Kenner (1974) described an empirical novelFlaubert, Joyce, and Beckett, for examplethat declines to be a Muses song, or even a mans intervention; it aspires, or feigns to aspire, to the truth of history, of scientific history (p. 70). 3. Mikhail Bakhtin: The novel can be defined as a diversity of speech types . . . a diversity of individual voices, artistically organized . . . The novel orchestrates all its themes, the totality of the world of objects and ideas depicted in it, by means of the diversity of speech types . . . and by the differing individual voices that flourish under such conditions (1981, p. 263). 4. All efforts to differentiate people across cultures or historical eras are overstated, dangerous, and still necessary; ignoring differences confuses the specifics of the present with the universal and invites arbitrary and unjust measures of excellence. The challenge is to use contrast sets as ways of seeing, not as stable realities. 5. For theory, see Shell, 1982; Goux, 1984/1994; Vernon, 1984; and Tratner, 2001. Also, see specific studies on the economics of, for example, Austen, Goethe, Poe, James, Trollope, Joyce, Hemingway, and William Carlos Williams. 6. So too, I think: Oliver Goldsmith with Adam Smith, Jane Austen with David Ricardo, Edith Wharton with Thorstein Veblen, Toni Morrison with John Kenneth Galbraith. 7. Educators can inquire into the contradictions of their own economic situation without accepting a blinding economic determinism. Marxs nuanced position (see Williams, 1977) should be less terrifying to educators than a confrontation with how they profit economically from reproducing the school problems they set out to solve. 8. Defoe even gives Molls momentary good fortune a sudden blow from an invisible hand (1722/1996, p. 166); see Rothschilds (2001) history of the invisible hand in Shakespeare, Adam Smith, and 20th-century economics. Defoe also stressed Marxs point

Political Economy of the Mind 157

that money gets money (Kibbie, 1995). 9. Defoes overstatement of the power of money has been echoed by anthropologists studying traditional societies transitioning to currency economies. Paul Bohannon called money one of the shatteringly simplifying ideas of all time, and like any other new and compelling idea, it creates its own revolution (1959, p. 503). As a generalized equivalent (Goux, 1984/1994; Marx, 1867/1976), money put the Tiv moral order on sale in West Africa. Since then, Bohannons strong language has been respecified by accounts of kinds of money, and ideologies of money, within and across multilayered societies (Bloch & Parry, 1989; Guyer, 2004; Maurer, 2005). Hurston (1934/1995) stumbled to the same point in a paper on Negro expression as a correlate to currency formation; for Hurston, said Michael Tratner (2001), the development of linguistic detachment is supported by and helps support in turn the development of economic detachment (p. 177; see also Hurston, 1934/1967). 10. Even as early apologists for individualism and capitalism, Defoe celebrated the wisdom of those on the bottom, and Mandeville scorned moralistic and self-congratulatory elites. 11. Mandeville: every Hour . . . the poor People spend at their Book is so much time lost to Society (1732/1924, p. 288). 12. Raymond Williams: All virtues of an alternative radicalism, of a central human vision of goodness and kindness and fullness of life which then creatively transcends, is made to transcend and surpass, the expositions and rationalizations of temporary interestsa movement, one might say, of conversion rather than persuasion, and of acts of transcendence rather than of conclusionare to be found in Dickens (1970, p. 87). 13. An easier formulation: A relatively weak propensity to consume helps to cause unemployment by requiring and not receiving the accompaniment of a compensating volume of new investment, which, even if it may sometimes occur temporarily through errors of optimism, is in general prevented from happening at all by the prospective profit falling below the standard set by the rate of interest (Keynes, 1936/1997, p. 370). 14. John Dewey on real learning: The more human the purpose, or the more it approximates the ends which appeal in daily experience, the more real the knowledge (1916, p. 198). 15. James was describing religion; see also Geertz (1999) quoting James and appreciating a more cultural approach to religion.

References

Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination (M. Holquist & C. Emerson, Eds.). Austin: University of Texas Press. Birdsall, V. O. (1985). Defoes perpetual seekers. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press. Bloch, M., & Parry, J. (1989). Introduction. In J. Parry & M. Bloch (Eds.), Money and the morality of exchange (pp. 131). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Bohannan, P. (1959). The impact of money on an African subsistence economy. Journal of Economic History, 19, 491503. Dean, M. (1991). The constitution of poverty. London: Routledge. Defoe, D. (1987). The complete English tradesman. Gloucester, England: Alan Sutton. (Original work published 1726) Defoe, D. (1989). Colonel Jack. London: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1722) Defoe, D. (1996). Moll Flanders. New York: Signet. (Original work published 1722)

158 National Society for the Study of Education

Defoe, D. (2004). Giving alms no charity and employing the poor as grievance to the nation. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger. (Original work published 1704) Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan. Dickens, C. (1993). Authors preface to the third edition. In C. Dickens, Oliver Twist: Authoritative text, backgrounds, early sources, early reviews, criticisms (pp. 37). New York: Norton. (Original work published 1841) Dickens, C. (1990a). Hard times: Authoritative text, backgrounds, early sources, early reviews, criticisms. New York: Norton. (Original work published 1854) Dickens, C. (1990b). On strike. In C. Dickens, Hard times: Authoritative text, backgrounds, early sources, early reviews, criticisms (pp. 285297). New York: Norton. (Original work published 1854) Gates, H. L. (1990). Zora Neale Hurston: A Negro way of saying. In Z. N. Hurston, Their eyes are watching God (pp. 185195). New York: Perennial Library. Geertz, C. (1999). The pinch of destiny. Raritan, 18(3), 119. Goux, J-J. (1994). The coiners of language. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. (Original work published 1984) Guyer, J. (2004). Marginal gains. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hirschman, A. (1997). The passions and the interests (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Hurston, Z.N. (1967). The gilded six-bits. In L. Hughes (Ed.), The best short stories by Black writers (pp. 7485). Boston: Little Brown. (Original work published 1934) Hurston, Z. N. (1990). Their eyes are watching God. New York: Harper Perennial Library. (Original work published 1937) Hurston, Z. N. (1995). Characteristics of Negro expression. In Zora Neale Hurston: Folklore, memoirs, and other writings (pp. 830846). New York: The Library of America. (Original work published 1934) James, W. (1982). The varieties of religious experience. New York: Barnes and Noble. (Original work published 1902) Kenner, H. (1974). The stoic comedians: Flaubert, Joyce, and Beckett. Berkeley: University of California Press. Keynes, J. M. (1997). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. New York: Prometheus. (Original work published 1936) Kibbie, A. L. (1995). Monstrous generation. PMLA, 110, 123134. Lave, J., & McDermott, R. (2002). Estranged learning. Outlines, 4, 1948. Mandeville, B. (1924). The fable of the bees: Or, private vices, publick benefits. 2 vols. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1732) Marx, K. (1976). Capital. London: Penguin. (Original work published 1867) Marx, K. (1982). A critique of political economy. New York: Progress. (Original work published 1859) Maurer, B. (2005). Mutual life, limited. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. McDermott, R. (2004). Materials for a confrontation with genius as a personal identity. Ethos, 32, 278288. Packer, M. (2002). Changing classes. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Plath, D. (1980). Long engagements. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Rampton, B. (2007). Language in late modernity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Roberts, D. (1989). Foreword. In D. Defoe, Colonel Jack (pp. viixxv). London: Oxford University Press. Rothschild, E. (2001). Economic sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet, and the Enlightenment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Political Economy of the Mind 159

Rousseau, J.-J. (1984). A discourse on the origins and foundations of inequality among men. London: Penguin. (Original work published 1754) Shell, M. (1982). Money, language, and thought: Literary and philosophic economies from the medieval to the modern era. Berkeley: University of California Press. Tobin, B. (1995). Superintending the poor. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Tratner, M. (2001). Deficits and desires. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Vernon, J. (1984). Money and fiction: Literary realism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Virno, P. (2008). Three remarks regarding the multitudes subjectivity and its aesthetic component. In D. Birnbaum & I. Grew (Eds.), Under pressure: Pictures, subjects, and the new spirit of capitalism (pp. 3145). Berlin, Germany: Sternberg Press. Webb, I. (1981). From custom to capital: The English novel and the industrial revolution. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Weber, M. (1998). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. Los Angeles: Roxbury. (Original work published 1904) Williams, R. (1970). Dickens and social ideas. In M. Slater (Ed.), Dickens 1970 (pp. 7798). New York: Stein and Day. Williams, R. (1977). Marxism and literature. London: Oxford University Press. Woodmansee, M. (1984). The genius and the copyright. Eighteenth Century Studies, 17, 425448.

RAY MCDERMOTT is a professor of education at Stanford University. For 40 years, he has used the tools of cultural analysis to critique how children learn, how schools work, and why Americans have invested so heavily in the institution of school failure. Recently, he has been working on the intellectual history of American ideas about learning, genius, and intelligence. He is the author (with Herv Varenne) of Successful Failure: The School America Builds (1998).

You might also like

- Dokumen - Pub - The Dutch Overseas Empire 16001800 1108449514 9781108449519Document481 pagesDokumen - Pub - The Dutch Overseas Empire 16001800 1108449514 9781108449519dgjdf hgjhdgNo ratings yet

- Idea of Progress - Teodar ShaninDocument7 pagesIdea of Progress - Teodar ShaninNaveenNo ratings yet

- The Child and Postmodern SubjectivityDocument13 pagesThe Child and Postmodern SubjectivityDavid Kennedy100% (2)

- Review of Fear of Small Numbers by A. AppaduraiDocument4 pagesReview of Fear of Small Numbers by A. AppaduraiLaura Pearl KayaNo ratings yet

- Roy Porter, Marie Mulvey Roberts (Eds.) - Pleasure in The Eighteenth CenturyDocument288 pagesRoy Porter, Marie Mulvey Roberts (Eds.) - Pleasure in The Eighteenth CenturyEduardoBragaNo ratings yet

- Ball Curve WarDocument8 pagesBall Curve WarWinda OuroraNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Dystopia ThesisDocument9 pagesBrave New World Dystopia Thesismelissawardbaltimore100% (2)

- Individuality in Tess of The DurbervillesDocument9 pagesIndividuality in Tess of The DurbervillesDiganta BorgohainNo ratings yet

- Literature and Cultural Production: AllegedlyDocument16 pagesLiterature and Cultural Production: AllegedlyDavidNo ratings yet

- Kelompok 4: 1. How To Differentiate The Three Major Schools of Comparatists (The French, The American, The Russian) ?Document8 pagesKelompok 4: 1. How To Differentiate The Three Major Schools of Comparatists (The French, The American, The Russian) ?Ovi SowinaNo ratings yet

- Varene McDermott With CorrectionDocument23 pagesVarene McDermott With CorrectionjhosyleinNo ratings yet

- Los Usos de La LiteraturaDocument7 pagesLos Usos de La LiteraturaDavid LuqueNo ratings yet

- Past and Present: The Challenges of Modernity, from the Pre-Victorians to the PostmodernistsFrom EverandPast and Present: The Challenges of Modernity, from the Pre-Victorians to the PostmodernistsNo ratings yet

- Misbehavioral SciencesDocument7 pagesMisbehavioral SciencesLance GoNo ratings yet

- Zipes Tales XDocument4 pagesZipes Tales XCe OmmNo ratings yet

- Popular Culture, Hegemony, and Captain AmericaDocument3 pagesPopular Culture, Hegemony, and Captain AmericaFrankNo ratings yet

- The Age of MerchantsDocument246 pagesThe Age of Merchantssergio dezorziNo ratings yet

- Hard Times As A Dickensian DystopiaDocument9 pagesHard Times As A Dickensian DystopianaalumthendralNo ratings yet

- Marxist Literary Theory XDocument3 pagesMarxist Literary Theory XibantoyNo ratings yet

- Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and MoralsFrom EverandFolkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and MoralsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- S I: N E S I Writing The Erasure of Emotions in Dystopian Young Adult Fiction: Reading Lois Lowry's TheDocument16 pagesS I: N E S I Writing The Erasure of Emotions in Dystopian Young Adult Fiction: Reading Lois Lowry's TheAlif KharuddinNo ratings yet

- Politics and Teen FictionDocument6 pagesPolitics and Teen FictionJames WatsonNo ratings yet

- Fear Definition EssayDocument8 pagesFear Definition Essayvdyvfjnbf100% (2)

- Edward Said Culture and ImperialismDocument6 pagesEdward Said Culture and ImperialismmairaNo ratings yet

- By Dermot Quinn: Almanac To Keynes's General Theory. Another Problem Is That They Have PowerDocument5 pagesBy Dermot Quinn: Almanac To Keynes's General Theory. Another Problem Is That They Have PowerJune KimNo ratings yet

- Disablity in Prose FictionDocument16 pagesDisablity in Prose Fictionall4bodee100% (1)

- Bianco 15: Bracketed For Gendered LanguageDocument14 pagesBianco 15: Bracketed For Gendered LanguageJillian LilasNo ratings yet

- Karl Stern Flight From WomanDocument7 pagesKarl Stern Flight From WomanSarban Malhans0% (1)

- (Download PDF) Microeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2Nd Edition Thomas Nechyba Full Chapter PDFDocument22 pages(Download PDF) Microeconomics An Intuitive Approach With Calculus 2Nd Edition Thomas Nechyba Full Chapter PDFnanieyeusope100% (9)

- Module Iii Books That Changed HistoryDocument16 pagesModule Iii Books That Changed HistoryLian Erica LaigoNo ratings yet

- FeedpaperDocument8 pagesFeedpaperapi-276665265No ratings yet

- T W E: M R M T: Introduction: Establishing The Ground of ContestationDocument22 pagesT W E: M R M T: Introduction: Establishing The Ground of ContestationKhalese woodNo ratings yet

- Oxford University PressDocument4 pagesOxford University PressNikos KalampalikisNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document7 pagesArticle 2Lala LandNo ratings yet

- AP Lang Q3 Argumentation Question 3 From Past ExamsDocument4 pagesAP Lang Q3 Argumentation Question 3 From Past ExamsSarah ShierNo ratings yet

- Eng PG-II CC-9 (Hard Times) DR Ravi K SinhaDocument4 pagesEng PG-II CC-9 (Hard Times) DR Ravi K Sinhajhjh32812No ratings yet

- Edward Said IntellectualsDocument4 pagesEdward Said Intellectualsmuhsain khanNo ratings yet

- THE HOUSE OF INTELLECT - J. BarzunDocument500 pagesTHE HOUSE OF INTELLECT - J. BarzunIntuição Radical0% (1)

- Mendelssohn - What Is Enlightenment?Document5 pagesMendelssohn - What Is Enlightenment?Giordano BrunoNo ratings yet

- The School Story: Young Adult Narratives in the Age of NeoliberalismFrom EverandThe School Story: Young Adult Narratives in the Age of NeoliberalismNo ratings yet

- Disability in Fairy Tales 2Document19 pagesDisability in Fairy Tales 2JesusMNo ratings yet

- Gned10 3rdimDocument24 pagesGned10 3rdimMaria Genica ColinaNo ratings yet

- A Level Mediastudies KeytermsDocument18 pagesA Level Mediastudies KeytermsFilozotaNo ratings yet

- Distopia Work PDFDocument33 pagesDistopia Work PDFÂnderson MartinsNo ratings yet

- A Critical Review of Benedict AndersonDocument7 pagesA Critical Review of Benedict AndersonMatt Cromwell100% (10)

- Readings - Social Sciences 129 PPDocument127 pagesReadings - Social Sciences 129 PPNigel IsaacNo ratings yet

- Politics and Teen FictionDocument5 pagesPolitics and Teen FictionJames WatsonNo ratings yet

- Perils of Protection: Shipwrecks, Orphans, and Children's RightsFrom EverandPerils of Protection: Shipwrecks, Orphans, and Children's RightsNo ratings yet

- +rebellion and Mental IllnessDocument63 pages+rebellion and Mental IllnessMaríaNo ratings yet

- Essay On Independence DayDocument5 pagesEssay On Independence Dayd3gxt9qh100% (2)

- IdentityDocument6 pagesIdentityChristina HernandezNo ratings yet

- Advice From Harvard: 10 Skills For Success in The Global EconomyDocument4 pagesAdvice From Harvard: 10 Skills For Success in The Global EconomyAlonso Muñoz PérezNo ratings yet

- Inglis Review by Blake Seidenshaw-2Document3 pagesInglis Review by Blake Seidenshaw-2Robert BranchNo ratings yet

- Essay On The IliadDocument6 pagesEssay On The Iliadheffydnbf100% (2)

- Underlying Themes in The Witchcraft of Seventeenthcentury New en 1970Document16 pagesUnderlying Themes in The Witchcraft of Seventeenthcentury New en 1970Rayane DouradoNo ratings yet

- Ortner - Generation X PDFDocument27 pagesOrtner - Generation X PDFataripNo ratings yet

- Critical Tradition and Ideological Positioning (Sarland)Document4 pagesCritical Tradition and Ideological Positioning (Sarland)viviana losaNo ratings yet

- The Racial Dimensions of Social Capital: Toward A New Understanding of Youth Empowerment and Community Organizing in America's Urban Core A. A. AkomDocument23 pagesThe Racial Dimensions of Social Capital: Toward A New Understanding of Youth Empowerment and Community Organizing in America's Urban Core A. A. AkomUrbanYouthJustice100% (1)

- Plea For Truthful Analysis of Ongoing EventsDocument3 pagesPlea For Truthful Analysis of Ongoing EventszizekNo ratings yet

- When They Read What We WriteDocument30 pagesWhen They Read What We WriteRodrgo GraçaNo ratings yet

- Izanagi Philosophical Views in Buying BehaviorDocument6 pagesIzanagi Philosophical Views in Buying BehaviorRegie BayaniNo ratings yet

- Fable of The Bees Mandeville PDFDocument2 pagesFable of The Bees Mandeville PDFChrisNo ratings yet

- Allegories of Farming From Greece and Rome Philosophical Satire in Xenophon, Varro, and Virgil PDFDocument236 pagesAllegories of Farming From Greece and Rome Philosophical Satire in Xenophon, Varro, and Virgil PDFSotirios Fotios Drokalos100% (1)

- Vries - The Industrial Revolution and The Industrious RevolutionDocument22 pagesVries - The Industrial Revolution and The Industrious Revolutionanton.de.rotaNo ratings yet

- Norman Barry, The Tradition of Spontaneous Order: A Bibliographical EssayDocument7 pagesNorman Barry, The Tradition of Spontaneous Order: A Bibliographical EssayAnonymous ORqO5yNo ratings yet

- Mandeville - Fable of The BeesDocument40 pagesMandeville - Fable of The Beesmpq91100% (1)

- Mandeville - ''The Fable of The Bees''Document410 pagesMandeville - ''The Fable of The Bees''Ivan SzytiukNo ratings yet

- Thomas A. Horne (Auth.) - The Social Thought of Bernard Mandeville - Virtue and Commerce in Early Eighteenth-Century England-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1978)Document134 pagesThomas A. Horne (Auth.) - The Social Thought of Bernard Mandeville - Virtue and Commerce in Early Eighteenth-Century England-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1978)包天誉No ratings yet

- Trancripts MOOC Classical Sociological TheoryDocument97 pagesTrancripts MOOC Classical Sociological TheoryHigoNo ratings yet

- In Conversation With Andre Beteille PDFDocument63 pagesIn Conversation With Andre Beteille PDFAnkur RaiNo ratings yet

- 2-Mandeville - Fable of The Bees PDFDocument45 pages2-Mandeville - Fable of The Bees PDFJorge RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Joseph Andrews Lecture 1Document7 pagesJoseph Andrews Lecture 1khushnood aliNo ratings yet

- Greed: Julian Edney, PHDDocument35 pagesGreed: Julian Edney, PHDJose G. VelezNo ratings yet

- The Industrial Revolution and The Industrious RevolutionDocument23 pagesThe Industrial Revolution and The Industrious RevolutionSimonaEsterMelisNo ratings yet

- 7 KAYE F.B. - The Writings of BMDocument50 pages7 KAYE F.B. - The Writings of BMlabm00911No ratings yet

- Lenguaje Politico Modern EUR Polemica ESP Indias Pagden PDFDocument374 pagesLenguaje Politico Modern EUR Polemica ESP Indias Pagden PDFAlberto NavasNo ratings yet

- Jesse DuplantisDocument10 pagesJesse DuplantisTimothyNo ratings yet

- Mandeville Early WorksDocument450 pagesMandeville Early WorksGuy DeboringNo ratings yet

- Pub - The English Novel in History 1700 1780 The Novel I PDFDocument290 pagesPub - The English Novel in History 1700 1780 The Novel I PDFMaida Khan100% (1)

- English Literature - The 18th Century - Britannica - Com - ANTONIO RESTANODocument25 pagesEnglish Literature - The 18th Century - Britannica - Com - ANTONIO RESTANODaniela SilvaNo ratings yet

- Self Love Egoism and The Selfish Hypothesis Key Debates From Eighteenth Century British Moral Philosophy 1st Edition Christian MaurerDocument70 pagesSelf Love Egoism and The Selfish Hypothesis Key Debates From Eighteenth Century British Moral Philosophy 1st Edition Christian Maurerlburiceclbm100% (4)

- CIA EthicsDocument76 pagesCIA EthicsGuy FalkNo ratings yet

- (1670 - 1733) Bernard Mandeville - The Fable of The BeesDocument3 pages(1670 - 1733) Bernard Mandeville - The Fable of The BeesdrpedrofNo ratings yet

- The Oldest ProfessionDocument7 pagesThe Oldest ProfessionEniko BodisNo ratings yet

- The Three Piece Suit and Modern MasculinityDocument7 pagesThe Three Piece Suit and Modern MasculinityYangyang MaoNo ratings yet

- Unveiling Fashion Business, Culture, and Identity in The Most Glamorous Industry by Frédéric Godart (Auth.)Document223 pagesUnveiling Fashion Business, Culture, and Identity in The Most Glamorous Industry by Frédéric Godart (Auth.)Daniela Arroyo100% (2)

- History ConsumerismDocument5 pagesHistory ConsumerismAna Popescu100% (1)