Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Santiago Alvarez DVD Review

Santiago Alvarez DVD Review

Uploaded by

gnatwareCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 2018 AP Chem MOCK FRQ FROM B Score GuideDocument15 pages2018 AP Chem MOCK FRQ FROM B Score GuideLena Nikiforov100% (1)

- Panofsky, Style and Medium in Motion PicturesDocument18 pagesPanofsky, Style and Medium in Motion Picturesnicolajvandermeulen100% (2)

- Arthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirDocument225 pagesArthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirDino246GT100% (3)

- Arthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirDocument225 pagesArthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirLakshmiNarayana PuttamchettyNo ratings yet

- L'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film ClassicsDocument35 pagesL'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film Classicsgrão-de-bico100% (5)

- Peter Brunette - Michael Haneke (Contemporary Film Directors)Document183 pagesPeter Brunette - Michael Haneke (Contemporary Film Directors)Jp Vieyra Rdz75% (4)

- JADT Vol4 n2 Spring1992 Fearnow Frick Antush Stavney MullenixDocument82 pagesJADT Vol4 n2 Spring1992 Fearnow Frick Antush Stavney Mullenixsegalcenter100% (1)

- 7 - Defectors To TelevisionDocument45 pages7 - Defectors To TelevisionMadalina HotoranNo ratings yet

- Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the EraFrom EverandWeimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the EraRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Michael HanekeDocument183 pagesMichael HanekeBogdan Neagu100% (1)

- Thomas Doherty - Brief History of MockumentaryDocument4 pagesThomas Doherty - Brief History of MockumentaryZéNo ratings yet

- Tesla Motors Expansion StrategyDocument26 pagesTesla Motors Expansion StrategyVu Nguyen75% (4)

- Da Compilação À CollageDocument11 pagesDa Compilação À Collagebutterfly2014No ratings yet

- Cinema & Culture - by Dudley AndrewDocument1 pageCinema & Culture - by Dudley AndrewOuahab HamzaNo ratings yet

- Merging Genres in The 1940s - The Musical and The Dramatic Feature FilmDocument12 pagesMerging Genres in The 1940s - The Musical and The Dramatic Feature FilmScott RiteNo ratings yet

- Bordwell ModernismDocument7 pagesBordwell ModernismMasha ShpolbergNo ratings yet

- From Fake Happyendings To Fake UnhappyendingsDocument11 pagesFrom Fake Happyendings To Fake UnhappyendingsLouis ChilsonNo ratings yet

- Photography and Cinematic SurfaceDocument5 pagesPhotography and Cinematic Surfacegeet666No ratings yet

- Video Views: Duran Duran, Billy Squier, Girl Groups: The Story of A Sound, Instant Replay: Video Music, Making Michael Jackson's ThrillerDocument3 pagesVideo Views: Duran Duran, Billy Squier, Girl Groups: The Story of A Sound, Instant Replay: Video Music, Making Michael Jackson's ThrillerFrank LoveceNo ratings yet

- A. Kaes - Silent CinemaDocument12 pagesA. Kaes - Silent CinemaMasha KolgaNo ratings yet

- Cozarinsky Sobre Cine ArgentinoDocument12 pagesCozarinsky Sobre Cine ArgentinoTango1680No ratings yet

- A Century of CinemaDocument6 pagesA Century of CinemawernickemicaNo ratings yet

- Of Cypresses and SunflowersDocument7 pagesOf Cypresses and SunflowersJOHN A WALKERNo ratings yet

- Silent Film-1 - NodrmDocument336 pagesSilent Film-1 - NodrmMarcelo RibaricNo ratings yet

- The Corsican Brothers and The Legacy of Its Tremulous 'Ghost Melody'Document12 pagesThe Corsican Brothers and The Legacy of Its Tremulous 'Ghost Melody'Scott RiteNo ratings yet

- Film Music History, An Overview of The Development of Music For FilmDocument6 pagesFilm Music History, An Overview of The Development of Music For FilmMano Dos Santos FranciscoNo ratings yet

- The Last Great American Picture Show - New Hollywood Cinema in The 1970sDocument395 pagesThe Last Great American Picture Show - New Hollywood Cinema in The 1970sRodrigo Ramos Estrada100% (6)

- Johan Van Der Keuken by Cohn ChambersDocument10 pagesJohan Van Der Keuken by Cohn ChambersEducacio VisualNo ratings yet

- Thomas - Elsaesser - Cinephilia or The Uses of DisenchantmentDocument17 pagesThomas - Elsaesser - Cinephilia or The Uses of DisenchantmentLuisa FrazãoNo ratings yet

- Silent FilmDocument13 pagesSilent FilmVictoria Elizabeth Barrientos Carrillo0% (1)

- CJ Film Studies61 Falkowska EuropeanDocument12 pagesCJ Film Studies61 Falkowska EuropeanEmilioNo ratings yet

- 20.3 Final PDFDocument110 pages20.3 Final PDFsegalcenterNo ratings yet

- Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film NoirFrom EverandStreet with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film NoirRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Recent History: The P Ist and Its Represei) T¿uioiis Prove Iheir Relevance Once AgainDocument4 pagesRecent History: The P Ist and Its Represei) T¿uioiis Prove Iheir Relevance Once AgainRobert BeaversNo ratings yet

- A Century of Cinema - Susan SontagDocument4 pagesA Century of Cinema - Susan Sontagcrisie100% (2)

- Arthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap - The Lost B Movies of Film Noir (2000, Da Capo Press) - Libgen - LiDocument225 pagesArthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap - The Lost B Movies of Film Noir (2000, Da Capo Press) - Libgen - LieveNo ratings yet

- A Grin Without A CatDocument5 pagesA Grin Without A CatlukuminaNo ratings yet

- Paul Schrader On Film NoirDocument6 pagesPaul Schrader On Film Noiralyssa5paulNo ratings yet

- Soundies Jukebox Films and the Shift to Small-Screen CultureFrom EverandSoundies Jukebox Films and the Shift to Small-Screen CultureNo ratings yet

- The Last GreatDocument395 pagesThe Last GreatJULIOALBANo ratings yet

- Orson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsDocument19 pagesOrson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsTheaethetus0% (1)

- Sound WavesDocument15 pagesSound WaveskuntokinteNo ratings yet

- DIY Art-Punk Video Tape Transgression - Blood KnifeDocument10 pagesDIY Art-Punk Video Tape Transgression - Blood Knifestellarastrology646No ratings yet

- Play It Again, or Old-Time Cuban Music On The ScreenDocument6 pagesPlay It Again, or Old-Time Cuban Music On The ScreenfadligmailNo ratings yet

- Edgar Neville - La Calle BordadoresDocument16 pagesEdgar Neville - La Calle BordadoresPablo Rubio GijonNo ratings yet

- Race'Ep!, Le FilmDocument9 pagesRace'Ep!, Le FilmathensprofNo ratings yet

- Orson Welles' Memo On by Lawrence FrenchDocument41 pagesOrson Welles' Memo On by Lawrence FrenchdovescryNo ratings yet

- Film CIA 1 Draft 1Document4 pagesFilm CIA 1 Draft 1Avinash K KuduvalliNo ratings yet

- ELSAESSER, Thomas. German Cinema - Seven Films For Seven DecadesDocument20 pagesELSAESSER, Thomas. German Cinema - Seven Films For Seven DecadesLucas ReisNo ratings yet

- Hungary Hamlet in Wonderland Miklós Jancsó's Nekem Lámpást Adott Kezembe As Úr Pesten (The Lord's Lantern in Budapest, 1998)Document14 pagesHungary Hamlet in Wonderland Miklós Jancsó's Nekem Lámpást Adott Kezembe As Úr Pesten (The Lord's Lantern in Budapest, 1998)Pedro Henrique FerreiraNo ratings yet

- John Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Document312 pagesJohn Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Andreea Cristina BortunNo ratings yet

- LDocument5 pagesLAnonymous v5EC9XQ30No ratings yet

- The Decay of CinemaDocument4 pagesThe Decay of CinemaBill VassiliosNo ratings yet

- Hanakova Czech ComedyDocument13 pagesHanakova Czech Comedyazucena mecalcoNo ratings yet

- Susan Sontag The Decay of Cinema PDFDocument4 pagesSusan Sontag The Decay of Cinema PDFabenasayagNo ratings yet

- The Art of John WilliamsDocument9 pagesThe Art of John WilliamsNoa TavorNo ratings yet

- Advanced QueuingDocument1,210 pagesAdvanced Queuingrishi10978No ratings yet

- Archer T5E (UN) - 1.0 Datasheet PDFDocument4 pagesArcher T5E (UN) - 1.0 Datasheet PDFeeerakeshNo ratings yet

- PragmaticsDocument10 pagesPragmaticsDisya RusmadinantiNo ratings yet

- 11.11th IPhO 1979Document11 pages11.11th IPhO 1979fienny37No ratings yet

- Essay On Flood in PakistanDocument6 pagesEssay On Flood in Pakistanjvscmacaf100% (2)

- 2012 GR 7 Maths PDFDocument8 pages2012 GR 7 Maths PDFmarshy bindaNo ratings yet

- Wed Sept 6 GeographyDocument17 pagesWed Sept 6 Geographyapi-367886489No ratings yet

- Bridget Wisnewski ResumeDocument2 pagesBridget Wisnewski Resumeapi-425692010No ratings yet

- S17.s1 - Final Project - Inglés 3 - MANUEL LAURA MAMANIDocument3 pagesS17.s1 - Final Project - Inglés 3 - MANUEL LAURA MAMANIManuel Sebastian Laura MamaniNo ratings yet

- What Is A Real Estate Investment Trust?: AreitisaDocument45 pagesWhat Is A Real Estate Investment Trust?: AreitisakoosNo ratings yet

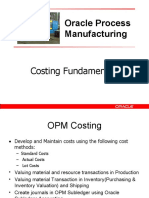

- OPM Costing Fundamentals - ActualDocument21 pagesOPM Costing Fundamentals - Actualkhaled_ghrbia100% (1)

- Game Sense ApproachDocument7 pagesGame Sense Approachapi-408626896No ratings yet

- ThinkPad X1 Carbon 6th Gen Datasheet enDocument3 pagesThinkPad X1 Carbon 6th Gen Datasheet enAnushree SalviNo ratings yet

- Controller Job DescriptionDocument1 pageController Job Descriptionmarco thompson100% (2)

- Nile International Freight ServicesDocument19 pagesNile International Freight ServicessameerhamadNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH - 2006 Read The Following Poem Carefully and Answer The Questions That Follow: (8 Marks) Forest FiresDocument6 pagesENGLISH - 2006 Read The Following Poem Carefully and Answer The Questions That Follow: (8 Marks) Forest FiresSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- 1 Heena - Front End UI ResumeDocument5 pages1 Heena - Front End UI ResumeharshNo ratings yet

- Hdat2en 4 52Document156 pagesHdat2en 4 52blahh12345689No ratings yet

- Resident Medical Officer KAmL4W116erDocument4 pagesResident Medical Officer KAmL4W116erAman TyagiNo ratings yet

- Chemrj 2016 01 06 09 16Document8 pagesChemrj 2016 01 06 09 16editor chemrjNo ratings yet

- Division of Rizal Summary of List of Learners Under Project AkapDocument3 pagesDivision of Rizal Summary of List of Learners Under Project AkapHELEN ASUNCIONNo ratings yet

- The Secret SharerDocument3 pagesThe Secret ShareranbarasiNo ratings yet

- Plasticity - Rubber PDFDocument3 pagesPlasticity - Rubber PDFsujudNo ratings yet

- Employee Uniform Agreement Sample Template 092321 3Document3 pagesEmployee Uniform Agreement Sample Template 092321 3zenithcrew.financeNo ratings yet

- Essay EnvironmentDocument4 pagesEssay Environmenttuevptvhd100% (2)

- Clause Based ChecklistDocument9 pagesClause Based ChecklistLim Kim YookNo ratings yet

- EPRG FrameworkDocument3 pagesEPRG FrameworkshalemNo ratings yet

- Sacred Science Publishes Financial Text Introducing The Planetary Time Forecasting MethodDocument2 pagesSacred Science Publishes Financial Text Introducing The Planetary Time Forecasting Methodkalai2No ratings yet

Santiago Alvarez DVD Review

Santiago Alvarez DVD Review

Uploaded by

gnatwareOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Santiago Alvarez DVD Review

Santiago Alvarez DVD Review

Uploaded by

gnatwareCopyright:

Available Formats

ing to watch the film in Russian v^'ith English subtitles should click, in the opening menu, on the word

"English," which simply indicates the language of the rest of the menu items and not that of the film. When curiosity led me to satnple the English-language version, I was shocked to discover that this consists of a single actor doing a simultaneous translation of the Russian dialog into English. No matter. This is an amazing Hamlet, and it can, happily, be easily ordered online from the Ruscico collection, where you can also obtain such goodies as Kozintsev's la.st film. King Lear (1969), which also features music by Shostakovich.Royal S. Brown

He Who Hits First Hits Twice:

The Urgent Cinema of Santiago Alvarez

Eight films by Santiago Alvarez, including Now, Cerro petado, Hanoi martes 13, Hasta la victoria siempre, L.B.J.. 79 primaveras. El Sueno del Pongo, and El tigre salto y mato. pero morira...morira, plus Travis Wilkerson's Accelerated Under-Developmeni, photo gallery and filniography. DVD, two discs, color and B&W. Distributed by Extreme Low Frequency, 3010 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90010, www.extremelowfTequency.com.

movie." But il would be hard to find a style of cinema more removed from the niceties of American television documentary than Alvarez's remarkably dynamic and bracingly radical montage constructions. Alvarez's work, pursued for forty years within the Cuban Eilm Institute (ICAIC) and its newsreel division Noticiero ICAIC, was a shining example of a 'poverty row' esthetic forged from necessity. His films wereas they are presented on this indispensable DVD compilationan example of 'urgent cinema," keyed to raising public consciousness about current issues such as racism, housing conditions and police brutality in various parts of the world. They are alsoin a reminder of the idealism that once accompanied cultural programs launched by socialist countriesdevoted to optimistic, somewhat romantic visions of a 'new society' with its reeducated and revitalized citizens. Howeverand here the contrast to Straub-Huillet or Godard-Gorin in the 196()s and '70s is extremethere is nothing heavily theoretical or 'obscurantist' about Alvarez's work. Its appeal is direct and highly emotive. It is impossible to watch films like Hanoi Martes !3 (1967), LBJ. (1968), or 79 Primaveras {1969) without being stirred by their api.>eals to justice and compassion. And the way in which Alvarez handles the combination ot photos, newsreel footage, music, and telegrammatic on-screen text (voice-over narration is generally eschewed) is luitailingly energetic and inventivecloser to the sensational 'tabloid' style of a Sam Fuller than the often overintellectualized assemblages of the contemporary 'essay-film.' Alvarez's filmmaking sensibility is nowhere more evident than in the gleefully brutal way that he refilms still photographs, as in Now (1965)jerking us, for instance, from the face of a white cop to the ugly truth of his clubbing a black man at the bottom of the frame. And all, in ihis case, cut to the swing of Lena Home: Alvarez was a master at creating juxtapositions of image

and sound that allowed for uplift, disquieting irony, and biting witfrequently all at once. The truly independent American filmmaker Travis Wilkerson (An Injury to One, 2002) has gathered eight representative films by Alvarez on the first disc of this DVI3, and added his own, invaluable documentary. Accelerated Under-Developmcnt, on the second. This essay-film is very much in the tradition of Chris Marker's The Last Bolshevik (1993), an account of the life and work of Soviet filmmaker Alexander Medvedkin. All of Alvarez's films were finished quickly with the collaborators he trained and supervised. Wilkerson tells us in his documentary and liner notes: 'They were never made with posterity in mind.' Is this why the print quality of the Alvarez films on this DVD is sometimes glaringly poor (with scratches, missing frames, some distorted sound)? Perhaps, with his own poverty-row budget, Wilkerson did not have the resources to digitally iron out these deficiencies, as more commercially-minded companies routinely do. Almost inevitably, Wilkerson's tribute to Alvarez has a mournful, nostalgic air exactly like Marker's excavation of Medvedkin. Is the charm of watching Alvarez in 2005 the charm of a 'lost cinema'not to mention the lost politics of a Socialist Utopia? As I watched, for the first time and in rapt amazement. El Tigre Salto y Mato, Pero Morira... MorirdU (\973)-for me, the most wonderful offering on this DVD, with its heartbreaking footage of the great Chilean singer-songwriter Victor fara performing "Te recuerdo Amanda"-I remembered the dinner-party gathering of old radicals ill Olivier Assayas's Irma Vep (1996), drinking wine, laughing, and dancing as they watched a Marker film of the Sixties with another Jara song on the soundtrack. A certain kind of engaged, even intoxicated political cinema seems, in that scene, like a fallen fragment from some planet that is long ago and far away, utterly alien to the concerns and audiovisual language of a contemporary postmodern culture. But then I thought again of the enormous difference between these inspired Cuban newsreels and the documentaries on cable television todayand, more specifically, between the Great Forgotten Alvarez and the Great Overrated Ken Burns. Where Burns's bloatediy epic, painfully lyricized photo-plusvoice-over pieces seem singlemindedly obsessed with rendering the all-American 'soul' (even when dealing with a phenomenon as complex and worldwide as jazz!), Alvarez contributed to a vigorous 'internationalist' vision in political cinema. His films either leapt over language barriers (by using pure image and music), or incorporated numerous languages within their on-screen text. It is precisely this 'multicultural' spiritthe will to energetically forge connections across national boundariesthat calls to us, out of the past, as something worth rediscovering and even emulating today.Adrian Martin

1 have always found that one can learn a k)t about a tllm or television program by running it through at fast speed. This is especially true of the type of documentary that appears on the Biography or History cable channels. What particularly pops out from such fast-forward viewing is the manner in which still photographs (usually of an archival variety) are treated: the elegant zooms and pans that lead the eye to what is deemed the significant detail. Where hardline formalist filmmakers like Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet have no qualms about giving us a photo 'straight," without any elaborate reframing and for an extended [.Tericxl of time on .screen, conventional television practice seems driven by a compulsion to 'animate' any potentially boring (because static) visual material. More recent developments in mainstream documentary, in fact, include using digital technology to discreetly set parts of a photo moving, or to create a 3D effect where the meaningful foreground is detached from the incidental background. Another wayindirect but forcefulto become aware of this complicated, sometimes rather sinister visual rhetoric in contemporary documentary is to watch the shorts of the Cuban filmmaker Santiago Alvarez (19191998). The basic elements of an Alvarez film are, after all, essentially tbe same as in many television documentaries: still photos edited to a soundtrack. In fact, Alvarez announced his esthetic credo in this way: "Give me two photos, music, iind a mo\'iola, and I'll give you a

Santiago Alvarez (1919-1998) (photo by Susan Fanshel, courtesy of Photofestl.

CINEASTE, Winter 2005 71

You might also like

- 2018 AP Chem MOCK FRQ FROM B Score GuideDocument15 pages2018 AP Chem MOCK FRQ FROM B Score GuideLena Nikiforov100% (1)

- Panofsky, Style and Medium in Motion PicturesDocument18 pagesPanofsky, Style and Medium in Motion Picturesnicolajvandermeulen100% (2)

- Arthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirDocument225 pagesArthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirDino246GT100% (3)

- Arthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirDocument225 pagesArthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap. The Lost B Movies of Film NoirLakshmiNarayana PuttamchettyNo ratings yet

- L'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film ClassicsDocument35 pagesL'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film Classicsgrão-de-bico100% (5)

- Peter Brunette - Michael Haneke (Contemporary Film Directors)Document183 pagesPeter Brunette - Michael Haneke (Contemporary Film Directors)Jp Vieyra Rdz75% (4)

- JADT Vol4 n2 Spring1992 Fearnow Frick Antush Stavney MullenixDocument82 pagesJADT Vol4 n2 Spring1992 Fearnow Frick Antush Stavney Mullenixsegalcenter100% (1)

- 7 - Defectors To TelevisionDocument45 pages7 - Defectors To TelevisionMadalina HotoranNo ratings yet

- Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the EraFrom EverandWeimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the EraRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Michael HanekeDocument183 pagesMichael HanekeBogdan Neagu100% (1)

- Thomas Doherty - Brief History of MockumentaryDocument4 pagesThomas Doherty - Brief History of MockumentaryZéNo ratings yet

- Tesla Motors Expansion StrategyDocument26 pagesTesla Motors Expansion StrategyVu Nguyen75% (4)

- Da Compilação À CollageDocument11 pagesDa Compilação À Collagebutterfly2014No ratings yet

- Cinema & Culture - by Dudley AndrewDocument1 pageCinema & Culture - by Dudley AndrewOuahab HamzaNo ratings yet

- Merging Genres in The 1940s - The Musical and The Dramatic Feature FilmDocument12 pagesMerging Genres in The 1940s - The Musical and The Dramatic Feature FilmScott RiteNo ratings yet

- Bordwell ModernismDocument7 pagesBordwell ModernismMasha ShpolbergNo ratings yet

- From Fake Happyendings To Fake UnhappyendingsDocument11 pagesFrom Fake Happyendings To Fake UnhappyendingsLouis ChilsonNo ratings yet

- Photography and Cinematic SurfaceDocument5 pagesPhotography and Cinematic Surfacegeet666No ratings yet

- Video Views: Duran Duran, Billy Squier, Girl Groups: The Story of A Sound, Instant Replay: Video Music, Making Michael Jackson's ThrillerDocument3 pagesVideo Views: Duran Duran, Billy Squier, Girl Groups: The Story of A Sound, Instant Replay: Video Music, Making Michael Jackson's ThrillerFrank LoveceNo ratings yet

- A. Kaes - Silent CinemaDocument12 pagesA. Kaes - Silent CinemaMasha KolgaNo ratings yet

- Cozarinsky Sobre Cine ArgentinoDocument12 pagesCozarinsky Sobre Cine ArgentinoTango1680No ratings yet

- A Century of CinemaDocument6 pagesA Century of CinemawernickemicaNo ratings yet

- Of Cypresses and SunflowersDocument7 pagesOf Cypresses and SunflowersJOHN A WALKERNo ratings yet

- Silent Film-1 - NodrmDocument336 pagesSilent Film-1 - NodrmMarcelo RibaricNo ratings yet

- The Corsican Brothers and The Legacy of Its Tremulous 'Ghost Melody'Document12 pagesThe Corsican Brothers and The Legacy of Its Tremulous 'Ghost Melody'Scott RiteNo ratings yet

- Film Music History, An Overview of The Development of Music For FilmDocument6 pagesFilm Music History, An Overview of The Development of Music For FilmMano Dos Santos FranciscoNo ratings yet

- The Last Great American Picture Show - New Hollywood Cinema in The 1970sDocument395 pagesThe Last Great American Picture Show - New Hollywood Cinema in The 1970sRodrigo Ramos Estrada100% (6)

- Johan Van Der Keuken by Cohn ChambersDocument10 pagesJohan Van Der Keuken by Cohn ChambersEducacio VisualNo ratings yet

- Thomas - Elsaesser - Cinephilia or The Uses of DisenchantmentDocument17 pagesThomas - Elsaesser - Cinephilia or The Uses of DisenchantmentLuisa FrazãoNo ratings yet

- Silent FilmDocument13 pagesSilent FilmVictoria Elizabeth Barrientos Carrillo0% (1)

- CJ Film Studies61 Falkowska EuropeanDocument12 pagesCJ Film Studies61 Falkowska EuropeanEmilioNo ratings yet

- 20.3 Final PDFDocument110 pages20.3 Final PDFsegalcenterNo ratings yet

- Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film NoirFrom EverandStreet with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film NoirRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Recent History: The P Ist and Its Represei) T¿uioiis Prove Iheir Relevance Once AgainDocument4 pagesRecent History: The P Ist and Its Represei) T¿uioiis Prove Iheir Relevance Once AgainRobert BeaversNo ratings yet

- A Century of Cinema - Susan SontagDocument4 pagesA Century of Cinema - Susan Sontagcrisie100% (2)

- Arthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap - The Lost B Movies of Film Noir (2000, Da Capo Press) - Libgen - LiDocument225 pagesArthur Lyons - Death On The Cheap - The Lost B Movies of Film Noir (2000, Da Capo Press) - Libgen - LieveNo ratings yet

- A Grin Without A CatDocument5 pagesA Grin Without A CatlukuminaNo ratings yet

- Paul Schrader On Film NoirDocument6 pagesPaul Schrader On Film Noiralyssa5paulNo ratings yet

- Soundies Jukebox Films and the Shift to Small-Screen CultureFrom EverandSoundies Jukebox Films and the Shift to Small-Screen CultureNo ratings yet

- The Last GreatDocument395 pagesThe Last GreatJULIOALBANo ratings yet

- Orson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsDocument19 pagesOrson Welles's The Trial Film Noir and The Kafkaesque - J. AdamsTheaethetus0% (1)

- Sound WavesDocument15 pagesSound WaveskuntokinteNo ratings yet

- DIY Art-Punk Video Tape Transgression - Blood KnifeDocument10 pagesDIY Art-Punk Video Tape Transgression - Blood Knifestellarastrology646No ratings yet

- Play It Again, or Old-Time Cuban Music On The ScreenDocument6 pagesPlay It Again, or Old-Time Cuban Music On The ScreenfadligmailNo ratings yet

- Edgar Neville - La Calle BordadoresDocument16 pagesEdgar Neville - La Calle BordadoresPablo Rubio GijonNo ratings yet

- Race'Ep!, Le FilmDocument9 pagesRace'Ep!, Le FilmathensprofNo ratings yet

- Orson Welles' Memo On by Lawrence FrenchDocument41 pagesOrson Welles' Memo On by Lawrence FrenchdovescryNo ratings yet

- Film CIA 1 Draft 1Document4 pagesFilm CIA 1 Draft 1Avinash K KuduvalliNo ratings yet

- ELSAESSER, Thomas. German Cinema - Seven Films For Seven DecadesDocument20 pagesELSAESSER, Thomas. German Cinema - Seven Films For Seven DecadesLucas ReisNo ratings yet

- Hungary Hamlet in Wonderland Miklós Jancsó's Nekem Lámpást Adott Kezembe As Úr Pesten (The Lord's Lantern in Budapest, 1998)Document14 pagesHungary Hamlet in Wonderland Miklós Jancsó's Nekem Lámpást Adott Kezembe As Úr Pesten (The Lord's Lantern in Budapest, 1998)Pedro Henrique FerreiraNo ratings yet

- John Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Document312 pagesJohn Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Andreea Cristina BortunNo ratings yet

- LDocument5 pagesLAnonymous v5EC9XQ30No ratings yet

- The Decay of CinemaDocument4 pagesThe Decay of CinemaBill VassiliosNo ratings yet

- Hanakova Czech ComedyDocument13 pagesHanakova Czech Comedyazucena mecalcoNo ratings yet

- Susan Sontag The Decay of Cinema PDFDocument4 pagesSusan Sontag The Decay of Cinema PDFabenasayagNo ratings yet

- The Art of John WilliamsDocument9 pagesThe Art of John WilliamsNoa TavorNo ratings yet

- Advanced QueuingDocument1,210 pagesAdvanced Queuingrishi10978No ratings yet

- Archer T5E (UN) - 1.0 Datasheet PDFDocument4 pagesArcher T5E (UN) - 1.0 Datasheet PDFeeerakeshNo ratings yet

- PragmaticsDocument10 pagesPragmaticsDisya RusmadinantiNo ratings yet

- 11.11th IPhO 1979Document11 pages11.11th IPhO 1979fienny37No ratings yet

- Essay On Flood in PakistanDocument6 pagesEssay On Flood in Pakistanjvscmacaf100% (2)

- 2012 GR 7 Maths PDFDocument8 pages2012 GR 7 Maths PDFmarshy bindaNo ratings yet

- Wed Sept 6 GeographyDocument17 pagesWed Sept 6 Geographyapi-367886489No ratings yet

- Bridget Wisnewski ResumeDocument2 pagesBridget Wisnewski Resumeapi-425692010No ratings yet

- S17.s1 - Final Project - Inglés 3 - MANUEL LAURA MAMANIDocument3 pagesS17.s1 - Final Project - Inglés 3 - MANUEL LAURA MAMANIManuel Sebastian Laura MamaniNo ratings yet

- What Is A Real Estate Investment Trust?: AreitisaDocument45 pagesWhat Is A Real Estate Investment Trust?: AreitisakoosNo ratings yet

- OPM Costing Fundamentals - ActualDocument21 pagesOPM Costing Fundamentals - Actualkhaled_ghrbia100% (1)

- Game Sense ApproachDocument7 pagesGame Sense Approachapi-408626896No ratings yet

- ThinkPad X1 Carbon 6th Gen Datasheet enDocument3 pagesThinkPad X1 Carbon 6th Gen Datasheet enAnushree SalviNo ratings yet

- Controller Job DescriptionDocument1 pageController Job Descriptionmarco thompson100% (2)

- Nile International Freight ServicesDocument19 pagesNile International Freight ServicessameerhamadNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH - 2006 Read The Following Poem Carefully and Answer The Questions That Follow: (8 Marks) Forest FiresDocument6 pagesENGLISH - 2006 Read The Following Poem Carefully and Answer The Questions That Follow: (8 Marks) Forest FiresSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- 1 Heena - Front End UI ResumeDocument5 pages1 Heena - Front End UI ResumeharshNo ratings yet

- Hdat2en 4 52Document156 pagesHdat2en 4 52blahh12345689No ratings yet

- Resident Medical Officer KAmL4W116erDocument4 pagesResident Medical Officer KAmL4W116erAman TyagiNo ratings yet

- Chemrj 2016 01 06 09 16Document8 pagesChemrj 2016 01 06 09 16editor chemrjNo ratings yet

- Division of Rizal Summary of List of Learners Under Project AkapDocument3 pagesDivision of Rizal Summary of List of Learners Under Project AkapHELEN ASUNCIONNo ratings yet

- The Secret SharerDocument3 pagesThe Secret ShareranbarasiNo ratings yet

- Plasticity - Rubber PDFDocument3 pagesPlasticity - Rubber PDFsujudNo ratings yet

- Employee Uniform Agreement Sample Template 092321 3Document3 pagesEmployee Uniform Agreement Sample Template 092321 3zenithcrew.financeNo ratings yet

- Essay EnvironmentDocument4 pagesEssay Environmenttuevptvhd100% (2)

- Clause Based ChecklistDocument9 pagesClause Based ChecklistLim Kim YookNo ratings yet

- EPRG FrameworkDocument3 pagesEPRG FrameworkshalemNo ratings yet

- Sacred Science Publishes Financial Text Introducing The Planetary Time Forecasting MethodDocument2 pagesSacred Science Publishes Financial Text Introducing The Planetary Time Forecasting Methodkalai2No ratings yet