Professional Documents

Culture Documents

R H - I E P R L: Epeated IGH Ntensity Xercise in A Rofessional Ugby Eague

R H - I E P R L: Epeated IGH Ntensity Xercise in A Rofessional Ugby Eague

Uploaded by

Louit LoïcOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

R H - I E P R L: Epeated IGH Ntensity Xercise in A Rofessional Ugby Eague

R H - I E P R L: Epeated IGH Ntensity Xercise in A Rofessional Ugby Eague

Uploaded by

Louit LoïcCopyright:

Available Formats

REPEATED HIGH-INTENSITY EXERCISE A PROFESSIONAL RUGBY LEAGUE

DAMIEN J. AUSTIN,1,2 TIM J. GABBETT,1,3

1

IN

AND

DAVID J. JENKINS1

School of Human Movement Studies, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Australia; 2Sydney Roosters Rugby League Club, New South Wales, Australia; and 3School of Exercise Science, Australian Catholic University, Brisbane, Australia

ABSTRACT

Austin, DJ, Gabbett, TJ, and Jenkins, DJ. Repeated highintensity exercise in a professional rugby league. J Strength Cond Res 25(7): 18981904, 2011The primary aim of this study was to identify and describe the frequency and duration of repeated high-intensity exercise (RHIE) bouts in Australian professional rugby league (National Rugby League) and whether these occurred at critical times during a game. Time motion analysis was used during 5 competition matches; 1 player from 3 positional groups (hit-up forward, adjustable, and outside back) was analyzed in each match. The ranges of RHIE bouts for the 3 positional groups were hit-up forwards 917, adjustables 28, and outside backs 37. Hit-up forwards were involved in a signicantly greater number of RHIE bouts (p , 0.05) and had the shortest average recovery (376 6 205 seconds) between RHIE bouts. The single overall maximum durations of RHIE bouts for the hit-up forwards, the adjustables, and the outside backs were 64, 64, and 49 seconds. For all groups, 70% of the total RHIE bouts occurred within 5 minutes prior of a try being scored. The present data show that the nature of RHIE bouts was specic to playing position and occurred frequently at critical times during the game. These results can be used to develop training programs that mimic the worst case scenarios that elite rugby league players are likely to encounter.

KEY WORDS time motion analysis, training, intermittent exercise INTRODUCTION

sprinting are central to the game and some research groups have suggested that repeated sprint ability (RSA) is a critical determinant to the outcome of a match (5,9,10), the occurrence of repeated high-intensity exercise (RHIE) relative to points scored is yet to be specically addressed in Rugby League. Research into high-intensity exercise, particularly in Rugby League, has been conned to the assessment of high-intensity running; tackling, for example, has not been included in evaluating the role and importance of high-intensity exercise. Given the exacting and demanding nature of tackling (coupled with the high frequency of tackles during a match), it is suggested that tackling be included in any further assessment of high-intensity exercise demands. Moreover, many previous studies that have provided information on sprint and multiple sprint activities in eld sports have reported average values rather than the most intense scenarios (2,4,5,9,10). However, it is maximal values that need to be built in to any training program developed as a result of TMA; using average data to develop training programs is not likely to best prepare players for the most intense periods of play they are likely to experience in competition. The purpose of this study was therefore to examine the nature (durations and frequencies) of RHIE in professional Rugby League and consider whether these occurred at critical times relative to points scored during a match. Tackling and sprinting were assessed with the view that the ndings could inform the development of training practices that could prepare players for the most demanding passages of play likely to be experienced in a game.

R

1898

ecent studies that have used time motion analysis (TMA) in professional Rugby League have conrmed that the accumulated distances sprinted by players during most games is relatively small compared to the total distances they cover in a match through forward or backward walking, jogging, and striding (57). Although it is recognized that sprinting and repeated

Address correspondence to: Damien Austin, damiena@sydneyroosters. com.au. 25(7)/18981904 Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2011 National Strength and Conditioning Association

METHODS

Experimental Approach to the Problem

Time motion analysis was used to evaluate the nature and frequency of RHIE undertaken by professional Rugby League players over several games. An RHIE bout was dened as 3 or more sprints, tackles or combination of both with ,21 seconds recovery between high-intensity efforts (modied from Spencer et al. [10] to include tackling).

Subjects

The movement patterns of 15 players from a professional rugby league club were recorded during 5 National Rugby League (NRL) games played in Australia during the 2008

TM

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the

Copyright National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the

TM

| www.nsca-jscr.org

TABLE 1. Differences in RHIE based on playing position.* HU Position First half Second half Match First half ADJ Second half Match First half OB Second half Match

Total RHIE 7 6 2 5 6 4 12 6 3 3 6 3 k 3 6 2k 6 6 3k 2 6 0k 3 6 1k 5 6 1k Total RHIE 220 6 88 154 6 129 374 6 96 81 6 79 64 6 55 145 6 94 43 6 9 77 6 36 120 6 39 duration (s) Average maximum 53 6 8 39 6 16 34 6 11 RHIE duration (s) Overall maximum 64 64 49 RHIE duration (s) 442 6 304 820 6 567 Average recovery 376 6 205 duration (s) between RHIE 42 55 55 Overall minimum recovery between RHIE (s)

*RHIE = repeated high-intensity exercise; HU = hit-up forwards; ADJ = adjustables; OB = outside backs. Values are mean 6 SD. Signicant difference (p , 0.05) compared to the HU forwards. Signicant difference (p , 0.05) compared to the outside backs. kSignicant difference (p , 0.05) compared to the adjustables.

season. This number of participants was greater than those used by King et al. (5) and similarly used by Sirotic et al. (10) with 17 players. Games were chosen 5 weeks apart (61 week) from January to September, and all were played at Suncorp Stadium, Brisbane. After consultation with the coaches, players were clustered into 3 positional groups. Five players in each of the 3 positional groups were assessed. The associated players in these positions were hit-up forwards (prop and second row), adjustables (halfback, hooker, ve-eighth, and lock), and outside backs (fullback, wing, and center). All subjects provided written informed consent before data collection. Ethics approval for all experimental procedures was granted by the Ethics Committee of The University of Queensland.

Procedures

Video recordings were made using 3 cameras (Hitachi DZGX5060SW, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) positioned on stationary tripods. Cameras were positioned on the halfway line approximately 30 m above the playing eld. This allowed a full view of the entire playing eld. Each camera operator followed 1 designated player for the entire duration of each match investigated. The zoom function of each video camera allowed each player to be lmed with a minimal radius of 10 m so as to allow a view of his surroundings and eld position. Each player was lmed for the entirety of the match, including breaks in play and time on the bench. The lming of 5 matches allowed for the averaging of data for each grouped playing position, differences in environment, oppositional standard and variations in refereeing.

The video footage was analyzed using a simple handnotation game analysis system; for each movement activity, frequency, distance covered, and duration were recorded. Movement was coded as 1 of 8 speeds of locomotion (standing, forward walking, backward walking, forward jogging, backward jogging, forward striding, forward sprinting, and lateral movement), one state of nonrunning intense exertion (e.g., tackling) or 1 discrete activity (e.g., kicking). These codes have been further dened previously (King et al. [5]). The uses of eld markings (10-m lines and sidelines) were used to reproduce as closely as possible the players location, speeds, and distances in activities. High-intensity work was considered to include forward striding, forward sprinting, and tackling. Low-intensity work included standing, forward and backward walking, and forward and backward jogging and lateral movement. Low-intensity activities were considered rest periods as opposed to highintensity activities that were classied as exercise. The duration of each interval of high-intensity work was divided by the duration of the following rest interval. This gave an exercise-torest ratio for that passage of play or game. An RHIE bout was dened as 3 or more sprints, tackles or combination of both with ,21-second recovery between high-intensity efforts (modied from Spencer et al. [10] to include tackling). Reliability of the TMA method was assessed by having another operator perform repeat analyses on one-half (ca. 40 minutes) of footage from 1 player. Intertester reliability was assessed by comparing analysis les from the 2 coders for the rst analysis, while comparing the repeated analyses for

VOLUME 25 | NUMBER 7 | JULY 2011 |

1899

Copyright National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Repeated High-Intensity Exercise in Rugby League

Figure 1. The percentage of average and overall maximum repeated high-intensity exercise (RHIE) bout separated into number of sprints (FSp), tackles (Tack) and other activities (standing, forward and backward walking, forward/backward jogging, forward striding, and lateral movements) during the whole match for players in the 3 positional groups. Values are mean 6 SD. Signicant difference (p ,0.05) compared to the hit-up forwards. HU = hit-up forwards, ADJ = adjustables, OB = outside backs.

coders assessed intratester reliability. Each experimenter was denied knowledge of results by the other experimenters, and approximately 4 weeks separated the rst and second analyses for intratester reliability. The imprecision of the coding technique was assessed using the typical error of

measurement (TE) (8). Previous studies have applied this method of reliability to TMA in rugby (3) and hockey (11). Typical error of measurement calculations were based on 4 measurements (frequency, total time, relative time [%], and relative distance [%]) of the 10 key movement modes

Figure 2. The percentage of sprinting (FSp) and tackling (Tack) in repeated high-intensity exercise (RHIE) during rst- and second-halves, and the whole match for players in the 3 positional groups. Values are mean 6 SD. Signicant difference (p , 0.05) compared to the hit-up forwards. HU = hit-up forwards, ADJ = adjustables, OB = outside backs.

1900

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the

TM

Copyright National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the

TM

| www.nsca-jscr.org

Figure 3. The percentage, mean (6SD) distance covered in sprinting movement, for players in the 3 positional groups. Values are mean 6 SD. Signicant difference (p ,0.05) compared to the hit-up forwards. HU = hit-up forwards, ADJ = adjustables, OB = outside backs.

(standing, forward walking, backward walking, forward jogging, backward jogging, striding, sprinting, lateral, tackling, and kicking). The TE (%) values for intracoder reliability for frequency, total time, relative time (%), and relative distance (%) were 2.6, 0.4, 9.3, and 5.2, respectively. The TE (%) values for intercoder reliability for frequency, total time, relative time (%), and relative distance (%) were 1.4, 0.2, 7.8, and 6.7, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

and the outside backs in total number of RHIE bouts in the rst and second halves of the games (3 6 3 and 3 6 2, and 2 6 0 and 3 6 1, respectively; p . 0.05). However, there was a difference for the hit-up forwards in the total number of RHIE bouts between the rst and second halves of the games (7 6 2 and 5 6 4, respectively) (p , 0.05), which is likely because of the less time spent by this group on the eld during the second half of the games.

Total Duration of Repeated High-Intensity Exercise per Game

Data for duration, percentage time, total time, number of activities, and mean duration and frequencies for activities and high-intensity exercise, are presented as means and SDs. The RHIE data were assessed through raw data calculations to format frequency, duration, activity proles, and also duration from a try being scored. Analysis of variance was used to establish differences in the variables among playing positions and residuals were checked for normality. If a difference between playing positions was found, a post hoc test (Tukey) was then used to locate the difference. All statistics were run on SPSS v17.0 for Windows with an alpha of 0.05 set a priori. Based on an alpha level of 0.05 and a sample size of 5 (number of players per position), the beta level (power) was .0.80 for detecting effect sizes of 0.5 or greater among individual playing positions for relative sprint distance (%), relative sprint duration (%), and relative time in high-intensity efforts (%).

The mean total times spent in RHIE per game for the hitup forwards, adjustables, and outside backs were 374 6 96, 145 6 94, and 120 6 39 seconds, respectively (Table 1). The hit-up forwards and adjustables tended to have greater total mean durations of RHIE in the rst half (220 6 88 and 81 6 79 seconds) when compared to the second half of the games (154 6 129 and 64 6 55 seconds) (p . 0.05). For the outside backs, the mean total durations of RHIE bouts for rst and second halves were 43 6 9 and 77 6 36 seconds, respectively (p . 0.05).

Average Maximum and Overall Maximum Durations of Repeated High-Intensity Exercise

RESULTS

Number of Repeated High-Intensity Exercise Bouts per Game

The mean maximum duration of RHIE bouts was higher for the hit-up forwards (53 6 8 seconds) than for both the adjustables (39 6 16) and the outside backs (34 6 11 seconds) (p , 0.05) (Table 1). The single overall maximum durations of RHIE bouts for the hit-up forwards, the adjustables, and the outside backs were 64, 64, and 49 seconds, respectively.

Number and Type of Activities in Overall Maximum Repeated High-Intensity Exercise Bouts

Hit-up forwards were involved in a signicantly greater (p , 0.05) number of RHIEs (12 6 3) when compared to the adjustables and outside backs (6 6 3 and 5 6 1, respectively) (Table 1). There was no difference between the adjustables

The hit-up forwards and adjustables had a signicantly greater number of activities (20 and 17 efforts, respectively) in a single

VOLUME 25 | NUMBER 7 | JULY 2011 |

1901

Copyright National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Repeated High-Intensity Exercise in Rugby League

Figure 4. The percentage of repeated high-intensity exercise (RHIE) in relation to duration before tries scored, during 5 matches for players in the 3 positional groups. HU = hit-up forwards, ADJ = adjustables, OB = outside back.

RHIE bout than the outside backs (9 efforts) (p , 0.05) (Figure 1). However, the hit-up forwards tended to spend the least amount of time in high-intensity efforts, such as sprinting and tackling (30%) within their maximal RHIE, compared to the adjustables and outside backs (41.2 and 55.5%, respectively), although this was not statistically signicant (p . 0.05). The outside backs tended to have the least percentage of efforts spent tackling (45.5%) when compared to the adjustables and hit-up forwards (58.8 and 60%), although this also was not statistically signicant (p . 0.05).

Percentage of Sprinting and Tackling Efforts in Repeated High-Intensity Exercise

was signicantly greater than for the adjustables (p , 0.05), and outside backs (p , 0.05). Hit-up forwards also sprinted more 11- to 20-m distances than the outside backs (p , 0.05). Of the sprints, 81.3% completed by the hit-up forwards were over 20 m or less, whereas the adjustables completed 82.7% of their sprints over 20 m or less (compared to 65.4% for the outside backs) (Figure 3). There was no signicant difference in sprinting distance .21 m between the 3 positional groups.

Recovery between Repeated High-Intensity Exercise

The hit-up forwards tended to have a higher percentage of their RHIE spent tackling (57%) than sprinting (43%), although this was not statistically signicant (p . 0.05). The percentage of tackling for the hit-up forwards was signicantly greater (p , 0.05) than for the adjustables (49.4%) and outside backs (40.5%). The adjustables spent almost the same amount of time sprinting and tackling (50.6 and 49.4%) in RHIE bouts. Based on the summation of RHIE activities, sprinting for the hit-up forwards (43%) was signicantly less than for both the adjustables (50.6%) (p , 0.05) and outside backs (59.5%) (p , 0.05) (Figure 2).

Distances Sprinted

The hit-up forwards tended to have the shortest recovery (376 6 205 seconds) between RHIE bouts compared to the adjustables (442 6 304 seconds) and outside backs (820 6 567 seconds), although, probably because of the high SDs, these values were not signicantly different between groups (p . 0.05) (Table 1). The adjustables and outside backs had the same minimum RHIE recovery durations (55 seconds, respectively), with the hit-up forwards minimum RHIE recovery time tending to be less (42 seconds) (p . 0.05).

Repeated High-Intensity Exercise Relative to Tries Scored

The majority of sprints for all positional groups were over a distance of 610 m (46.1, 39.4, and 32.4% for the hit-up forwards, adjustables, and outside back groups, respectively). For the hit-up forwards, the percentage of sprints over 610 m

The team studied won 3 of the 5 games played; the team scored 25 tries and 24 goals (conversions), whereas the opposition teams scored 18 tries and 17 goals. During the 5 games, the studied team attempted no eld goals. All 3 playing positions had relatively similar percentages of their total RHIE bouts occur within 60 seconds of tries being scored; outside backs had the highest percentage of total RHIE at 12%, compared to hit-up forwards (11.3%) and adjustables (10.7%) (p . 0.05). The percentage of total RHIE

1902

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the

TM

Copyright National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

bouts immediately preceding (0 seconds) a try was highest for the hit-up forwards (6.5%), followed by the adjustables (3.6%); there was no RHIE bout that immediately preceded a try for the outside backs. Therefore, of the 3 positional groups, hit-up forwards engaged in 80% of the total number of RHIE immediately before a try (0 seconds). When RHIE bouts occurred within 30 seconds of a try being scored, the only percentage change was found for the hit-up forwards; 9.7% of the total RHIE bouts completed by the hit-up forwards occurred within 30 seconds. Within 60 seconds of a try being scored, the hit-up forwards carried out 53.8% of the total RHIE bouts completed by the 3 positional groups. Both the adjustables and outside backs completed 23.1% of total RHIE bouts within 60 seconds of a try. The outside backs had the greatest percentage (44%) of total RHIE bouts that occurred within 5 minutes (,300 seconds) of a try being scored. This compares to 37.5% for the adjustables and 32.3% for the hit-up forwards (Figure 4). For all groups, 70% of the total RHIE bouts occurred within 5 minutes prior of a try being scored.

the

TM

| www.nsca-jscr.org

DISCUSSION

The aims of this study were to identify and describe the frequency and duration of RHIE bouts in professional rugby league and consider whether these activities occurred at critical times during a game (i.e., immediately before points being scored). The present data show that the nature of RHIE bouts was specic to playing position and occurred frequently at critical times during the game. The ability of players to repeat high-intensity exercise (similar to RSA, proposed by Spencer et al. [10]) is recognized as being central to elite performance in eld sports that are characterized by intermittent sprints. Indeed, some researchers have suggested that RHIE bouts occur at critical phases of a match (1,9). The range of RHIE bouts over the 5 games for the 3 positional groups in this study were hit-up forwards 917, adjustables 28, and outside backs 37. The hit-up forwards spent an average of 26.6% less time on the eld than the adjustables and outside backs, yet they completed a signicantly greater number of RHIE bouts per game. The shorter game time for the hit-up forwards almost certainly reects the very high-intensity nature of the work demanded of them when they were on the eld. These positional ranges are signicantly greater than the 03 range of repeated sprints (RSA) reported in rugby league by Sirotic et al. (9). The inclusion of tackling with sprinting in the present study signicantly increases the estimation of high-intensity exercise that players engage in. Given the known high physical demands of tackling, coupled with the importance of this particular skill on the outcome of a game, one can reasonably argue that any assessment of high-intensity exercise in rugby league must include tackling and sprint exercise.

King et al. (5) reported that the average high-intensity exercise time performed by their players without rest was 4 seconds, with the longest exercise period being 35 seconds. The data reported by King et al. (5) are single efforts of highintensity exercise, and not a collection of 3 or more highintensity efforts, such as RHIE used in this study. This study showed the average duration of RHIE bouts over the 5 games was the same for the adjustables and outside backs and averaged 24 seconds; RHIE bouts for the hit-up forwards averaged 30 seconds. When the average maximum duration of RHIE bouts over the 5 games are considered, the hit-up forwards were engaged for a maximum of 53 seconds. In contrast, the maximum durations of RHIE bouts for the adjustables and outside backs were 39 and 34 seconds, respectively. The present maximal RHIE data show that average data do not accurately reect the most intense passages that a player is likely to experience in a game. For players to be adequately prepared for the most intense passages of play, they are likely to experience in competition, conditioning coaches need to use maximal values rather than average values to design their training programs. The most intense single RHIE bout based on total duration was achieved by an adjustable, at 64 seconds. This involved 6 high-intensity activities (4 sprints and 2 tackles), and the player covered a total distance of 104 m. There were 17 changes in activity and sprint distances ranged from 8 to 12 m. The most intense single RHIE bout achieved by a hit-up forward lasted 64 seconds but involved 20 activities. Ninety meters were covered during this bout (including 1 sprint of 7 m), and the player completed 5 tackles. For the outside backs, the most intense RHIE bout lasted 49 seconds, covered a total distance of 66 m, and included 9 activities; 5 of these were high-intensity in nature, and there were 3 sprints ranging from 10 to 18 m in addition to 2 tackles. Although previous research (5,9,10) has reported the frequency of RHIE involving sprints, the duration between a player required to perform another RHIE bout has not been studied. Of the 3 positional groups, the hit-up forwards had the shortest average recovery (376 seconds) between RHIE bouts; recovery for the adjustables and outside backs averaged 442 and 820 seconds, respectively. The minimum RHIE recovery durations for the adjustables and outside backs were the same (55 seconds, respectively), whereas the minimum RHIE recovery time for the hit-up forwards was 41.7 seconds. For all 3 positional groups, the majority of their RHIE bouts involved 3 high-intensity activities, such as sprinting and tackling. The hit-up forwards and adjustables were involved in a majority of RHIE bouts that included 1 sprint and 2 tackles (29.5 and 37% of RHIE in total). The conguration of 2 sprints and 1 tackle was the second highest combination of efforts in an RHIE bout for hit-up forwards and adjustables (16.4 and 22.2%, respectively); however 2 sprints and 1 tackle comprised 58.3% of total RHIE for outside backs. This demonstrates the need to include tackling, as a high-intensity effort, as opposed to just

VOLUME 25 | NUMBER 7 | JULY 2011 |

1903

Copyright National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Repeated High-Intensity Exercise in Rugby League

sprinting referred to by Sirotic et al. (9) as tackling plays an important facet for the varying playing positions. This study found for the 3 positional groups, most sprints (39.3%) were over distances of between 6 and 10 m, followed by distances of between 11 and 20 m (28%). These distances are shorter than those reported by Meir et al. (6); those authors found that most sprints were between 10 and 20 m. Meir et al. (7) do not comment on changes in average sprint distances after the 10-m rule was introduced. The present ndings are similar to those of King et al. (5) who found that hit-up forwards generally sprinted 56 m, whereas the adjustables generally sprinted 812 m. The outside backs generally sprinted greater distances, but ranges were not reported by the authors (5). In this study, both the hit-up forwards and adjustables completed over half of their sprints (55.4 and 51.7%, respectively) over distances ,10 m; 38.2% of the sprints completed by the outside backs were over a distance ,10 m. Eighty percent of all sprints completed by the hit-up forwards and adjustables were ,20 m in distance, whereas the outside backs completed 80% of their sprints over distances ,30 m. Outside backs were found to have the highest percentage of sprinting distance over 40 m (at 9.8% of their total sprints), compared to 4.7 and 4.5% for the same distance covered by hit-up forwards and the adjustables. These ndings impress the need for training programs to take into account that most sprints in a game occur over distances ,20 m for hit-up forwards and adjustables, and over slightly longer distances (30 m) for outside backs. Both Spencer et al. (10) and King et al. (5) suggest that bouts of particularly high-intensity exercise (e.g., RHIE) are often critical to the outcome of many games, inuence points being scored and also occur close to either the opposition goal line (in attack) or the defending goal line. Hit-up forwards were found to performed 86% of all RHIE bouts within 30 seconds of a try being scored. By comparison, 23% of RHIE bouts for the adjustables and outside backs occurred within 30 seconds of a try being scored. When the 3 positional groups were considered together, 70% of RHIE bouts occurred with 5 minutes of tries being scored. The proximity of RHIE bouts to tries scored not only varied relative to positional group but there were also differences relative to whether their own team scored or whether the opposition scored. For the hit-up forwards, 55 and 45% of RHIERIHE bouts occurred within 5 minutes of tries being scored by their own team and the opposition team, respectively. For the adjustables 67 and 33% of the RIHE bouts occurred within 5 minutes of their own team scoring a try and the opposition scoring a try (respectively). The outside backs were found to have the greatest percentage of RHIE bouts preceding their own tries; 83% of RHIE bouts occurred within 5 minutes of a try for this group. Outside backs therefore had a greater percentage of RHIE bouts immediately before their own team scoring, as opposed to hit-up forwards for whom there were roughly equal percentages of RHIE bouts that occurred in attack and defense.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

This study has shown the importance of RHIE bouts in relation to points being scored and that the duration and activities of RHIE bouts differ relative to playing position. The present data can be used to develop training programs that mimic the worst case scenarios (in the context of RHIE demands) that elite rugby league players are likely to encounter in competition. Training programs should replicate the different RHIE activities the various positions use most frequently. Training programs that develop each players capacity to frequently undertake RHIE with minimal periods of recovery may be expected to inuence the outcome of a game.

REFERENCES

1. Dawson, B, Fitzsimmons, M, and Ward, D. The relationship of repeated sprint ability to aerobic power and performance measures of anaerobic work capacity and power. Aust J Sci Med Sport 25: 8393, 1993. 2. Duthie, G, Pyne, D, and Hooper, S. The applied physiology and game analysis of rugby union. Sports Med 33: 973991, 2003. 3. Duthie, G, Pyne, D, and Hooper, S. Time motion analysis of 2001 and 2002 super 12 rugby. J Sports Sci 23: 523530, 2005. 4. Edgecomb, S and Norton, K. Comparison of global positioning and computer-based tracking systems for measuring player movement distance during Australian Football. J Sci Med Sport 9: 2532, 2006. 5. King, T, Jenkins, D, and Gabbett, T. A time-motion analysis of professional rugby league match-play. J Sports Sci 27: 213219, 2009. 6. Meir, R, Arthur, D, and Forrest, M. Time and motion analysis of professional rugby league: A case study. Strength Cond Coach 1: 15, 1996. 7. Meir, R, Colla. P, and Milligan, C. Impact of the 10-metre rule change on professional rugby league: Implications for training. Strength Cond J 23: 4246, 2001. 8. Mueller, W and Martorell, R. Reliability and accuracy of measurement. In: Anthropometric Standardisation Reference Manual. T.G. Lohman, A.F. Roche, and R. Martorell, eds. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1990. pp. 8386. 9. Sirotic, A, Coutts, A, Knowles, H, and Catterick, C. A comparison of match demands between elite and semi-elite rugby league competition. J Sports Sci 27: 203211, 2009. 10. Spencer, M, Lawerence, S, Rechichi, C, Bishop, D, Dawson, B, and Goodman, C. Time-motion analysis of elite eld hockey, with special reference to repeated-sprint activity. J Sports Sci 22: 843850, 2004. 11. Spencer, M, Lawerence, S, Rechichi, C, Bishop, D, Dawson, B, and Goodman, C. Time-motion analysis of elite eld hockey during several games in succession: A tournament scenario. J Sci Med Sport 4: 382391, 2005.

1904

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the

TM

Copyright National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- Blood Bowl - The Offical RulesDocument60 pagesBlood Bowl - The Offical Rulesmortifaguillo100% (22)

- Winkelman Nick Learning To Sprint 40th 0Document34 pagesWinkelman Nick Learning To Sprint 40th 0Louit Loïc100% (11)

- List Kad Matrik KL Ja182 PDFDocument3 pagesList Kad Matrik KL Ja182 PDFPutera Mohamad FaridNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Changes of Direction, Multidirectional Displacements, Team Sport, AthletesDocument14 pagesKeywords: Changes of Direction, Multidirectional Displacements, Team Sport, AthletesmelakuNo ratings yet

- Accepted: Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Publish Ahead of Print DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001470Document27 pagesAccepted: Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Publish Ahead of Print DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001470Felipe ReyesNo ratings yet

- Hoff, JR (2003) The Effect of An Intercollegiate Soccer Game On Maximal Power PerformanceDocument11 pagesHoff, JR (2003) The Effect of An Intercollegiate Soccer Game On Maximal Power PerformanceMario0405No ratings yet

- Effects of Static Stretching On Repeated Sprint and Change of Direction PerformanceDocument7 pagesEffects of Static Stretching On Repeated Sprint and Change of Direction Performancemehdi.chlif4374No ratings yet

- JA2 Post412 VariabilityDocument4 pagesJA2 Post412 VariabilityOscarDavidGordilloGonzalezNo ratings yet

- Relationships Between Repeated Sprint TeDocument5 pagesRelationships Between Repeated Sprint TeMelany ReinaNo ratings yet

- Applied Sport Science of Rugby LeagueDocument14 pagesApplied Sport Science of Rugby LeagueHani AssiNo ratings yet

- JA2 Post412 ReliabilityDocument10 pagesJA2 Post412 ReliabilityOscarDavidGordilloGonzalezNo ratings yet

- Enhancing High-Intensity Actions During A Basketball Game After A Strength Training Program With Random Recovery Time 2022Document22 pagesEnhancing High-Intensity Actions During A Basketball Game After A Strength Training Program With Random Recovery Time 2022Jean Claude HabalineNo ratings yet

- Core Strength A New Model For Injury Prediction and PreventionDocument8 pagesCore Strength A New Model For Injury Prediction and PreventionYoh ChenNo ratings yet

- Cormack Et Al. (2013) - Impact of NM Fatigue On Accelerometer Load in Elite Aussie FootballDocument6 pagesCormack Et Al. (2013) - Impact of NM Fatigue On Accelerometer Load in Elite Aussie FootballHusan ThapaNo ratings yet

- JSCR 2011 Stretching FDDocument8 pagesJSCR 2011 Stretching FDJonatas GomesNo ratings yet

- SCOTT Tannath-Thesis - NosignatureDocument232 pagesSCOTT Tannath-Thesis - Nosignaturedaniela gabarinNo ratings yet

- JA2 Post412 DemandsDocument7 pagesJA2 Post412 DemandsOscarDavidGordilloGonzalezNo ratings yet

- Campos VazquezDocument25 pagesCampos VazquezMartín Seijas GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Specific Incremental Field Test For Aerobic Fitness in TennisDocument6 pagesSpecific Incremental Field Test For Aerobic Fitness in TennisCATALINA BUITRAGO OROZCONo ratings yet

- E M I H - I R P E FAP L S M: Valuation of The OST Ntense IGH Ntensity Unning Eriod in Nglish Remier Eague Occer AtchesDocument7 pagesE M I H - I R P E FAP L S M: Valuation of The OST Ntense IGH Ntensity Unning Eriod in Nglish Remier Eague Occer AtchesStefano LivieraNo ratings yet

- ATest To Evaluate The Physical Impact On Technical Performance in SoccerDocument10 pagesATest To Evaluate The Physical Impact On Technical Performance in SoccerDejan SaveskiNo ratings yet

- Validity of A Repeated-Sprint Test For Football: Authors AffiliationsDocument7 pagesValidity of A Repeated-Sprint Test For Football: Authors AffiliationsAhmad Sabarani Archery AhmadNo ratings yet

- SC. 2014 Owen IJSM Physical and Technical Comparisons Between Various-Sided Games Within Professional SoccerDocument7 pagesSC. 2014 Owen IJSM Physical and Technical Comparisons Between Various-Sided Games Within Professional SoccerKar Yau MakNo ratings yet

- Position Specific Rehabilitation For Rugby Union Players. Part I: Empirical Movement Analysis DataDocument8 pagesPosition Specific Rehabilitation For Rugby Union Players. Part I: Empirical Movement Analysis DataAntonio MartinezNo ratings yet

- Technical Activity Profile and Influence of Body.36Document13 pagesTechnical Activity Profile and Influence of Body.36Martiniano Vera EnriqueNo ratings yet

- Speed Endurance LiverpoolDocument12 pagesSpeed Endurance LiverpoolmattiaNo ratings yet

- Young Investigator Research Article: Mindaugas Balčiūnas, Stanislovas Stonkus, Catarina Abrantes and Jaime SampaioDocument8 pagesYoung Investigator Research Article: Mindaugas Balčiūnas, Stanislovas Stonkus, Catarina Abrantes and Jaime SampaioLeonardiniNo ratings yet

- Williams 20-20 Suitability 20 of 20 Soccer 20 Training 20 DrillsDocument5 pagesWilliams 20-20 Suitability 20 of 20 Soccer 20 Training 20 DrillsDeyan SyambasNo ratings yet

- 489321-Texto Del Artículo-1972441-1-10-20221031Document9 pages489321-Texto Del Artículo-1972441-1-10-20221031Viviana ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- Evaluaciòn de La Condiciòn Fisica y AntropometricaDocument9 pagesEvaluaciòn de La Condiciòn Fisica y AntropometricaDVD FUTBOLNo ratings yet

- Sprint vs. Interval Training in FootballDocument7 pagesSprint vs. Interval Training in Footballb07flmNo ratings yet

- 2017 APNMCluster RTDocument12 pages2017 APNMCluster RTAdrián Monterior BellidoNo ratings yet

- Laios 2011 Receiving and Serving Team Efficiency in VolleyballDocument10 pagesLaios 2011 Receiving and Serving Team Efficiency in Volleyballyago.pessoaNo ratings yet

- Correlation Between Match Performance and Field Tests in Professional Soccer PlayersDocument7 pagesCorrelation Between Match Performance and Field Tests in Professional Soccer PlayersJUAN GERMAN GARZON MOLINANo ratings yet

- Effect of CST Versus RST On Physical Parameters in College Level Football PlayersDocument8 pagesEffect of CST Versus RST On Physical Parameters in College Level Football PlayersInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The Effect of In-Season Traditional and Explosive Resistance Training Programs On Strength, Jump Height, and Speed in Recreational Soccer PlayersDocument9 pagesThe Effect of In-Season Traditional and Explosive Resistance Training Programs On Strength, Jump Height, and Speed in Recreational Soccer PlayersTem ginastica?No ratings yet

- Impellizzeri Et Al Validity of A Repeated-Sprint Test For FootballDocument16 pagesImpellizzeri Et Al Validity of A Repeated-Sprint Test For FootballAhmad Sabarani Archery AhmadNo ratings yet

- Training Periodization Over An Elite Rugby Sevens Season - From Theory To Practice PDFDocument10 pagesTraining Periodization Over An Elite Rugby Sevens Season - From Theory To Practice PDFDouglas MarinNo ratings yet

- Cousins 2022 Trainingand Match Demandsof Elite Rugby UnionDocument8 pagesCousins 2022 Trainingand Match Demandsof Elite Rugby UnionLeandro LuceroNo ratings yet

- Owen Et Al. (2012) Effects of A Periodized Small-Sided Game Training Intervention On...Document7 pagesOwen Et Al. (2012) Effects of A Periodized Small-Sided Game Training Intervention On...Ravi CaminhanteNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Whole Body Resistance Band Training On Physical Parameters in Male Cricketers - RCT StudyDocument15 pagesEfficacy of Whole Body Resistance Band Training On Physical Parameters in Male Cricketers - RCT StudyDr Usha PTNo ratings yet

- Energy System Requirements of Soccer PlayerDocument40 pagesEnergy System Requirements of Soccer PlayerLena Kovacevic100% (1)

- TN Nessen 2011Document7 pagesTN Nessen 2011Tomas ParraguezNo ratings yet

- Demands of Top Class Soccer Refereing in Relation To Physical CapacityDocument12 pagesDemands of Top Class Soccer Refereing in Relation To Physical CapacityPaulo SandiNo ratings yet

- Streching FutbolDocument5 pagesStreching FutbolPedro VelázquezNo ratings yet

- JSC 0b013e3181c7c5fdDocument6 pagesJSC 0b013e3181c7c5fdKeep AskingNo ratings yet

- s40279-023-01959-1Document22 pagess40279-023-01959-1krm.yldzzzNo ratings yet

- Rampinini 2007Document9 pagesRampinini 2007Dylan VenegasNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Endocrine and Perceptual Fatigue Responses During Different Length Between Match Microcycles in RugbyDocument17 pagesNeuromuscular Endocrine and Perceptual Fatigue Responses During Different Length Between Match Microcycles in RugbyjavierNo ratings yet

- A Clustered Repeated-Sprint Running Protocol For Team-Sport Athletes Performed in Normobaric HypoxiaDocument7 pagesA Clustered Repeated-Sprint Running Protocol For Team-Sport Athletes Performed in Normobaric HypoxiaRodulfo AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Barr 2015Document8 pagesBarr 2015asepsumpenaNo ratings yet

- Krvavi PrdezDocument34 pagesKrvavi PrdezgvozdenNo ratings yet

- Effects of High Intensity Interval Training With.96125Document31 pagesEffects of High Intensity Interval Training With.96125Martiniano Vera EnriqueNo ratings yet

- JA2 Post412 PerformanceDocument10 pagesJA2 Post412 PerformanceOscarDavidGordilloGonzalezNo ratings yet

- 111Document12 pages111manishaNo ratings yet

- Chtara 2017 Biology of SportDocument12 pagesChtara 2017 Biology of SportDiegoNo ratings yet

- Short Term Effects of Complex and ContrastDocument6 pagesShort Term Effects of Complex and ContrastKoordinacijska Lestev Speed LadderNo ratings yet

- Effects of Inter Limb AsymmetriesDocument24 pagesEffects of Inter Limb AsymmetriesTadija TrajkovićNo ratings yet

- 2002 The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Physiological Response, Reliability, and ValidityDocument9 pages2002 The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Physiological Response, Reliability, and ValidityFrancisco Antonó Castro WeithNo ratings yet

- Buchheit Stiffness Responses To Football Conditionned SessionsDocument15 pagesBuchheit Stiffness Responses To Football Conditionned SessionsPabloAñonNo ratings yet

- Relationships Between Ground Reaction Impulse And.2Document6 pagesRelationships Between Ground Reaction Impulse And.2Andrew ShirekNo ratings yet

- 80/20 Endurance: The Complete System for High-Performance CoachingFrom Everand80/20 Endurance: The Complete System for High-Performance CoachingNo ratings yet

- 24 Shoulder PDFDocument3 pages24 Shoulder PDFLouit LoïcNo ratings yet

- Friday 3 BakerDocument0 pagesFriday 3 BakerLouit LoïcNo ratings yet

- Friday 3 BakerDocument0 pagesFriday 3 BakerLouit LoïcNo ratings yet

- History of Football in EnglandDocument17 pagesHistory of Football in EnglandAndrei ZvoNo ratings yet

- My - Stats - ControleDocument2 pagesMy - Stats - ControleIvan Luis CeccatoNo ratings yet

- Girls All-State SoccerDocument1 pageGirls All-State SoccerHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNo ratings yet

- La Casa de Tips - ListasDocument3 pagesLa Casa de Tips - ListasDaniel LucasNo ratings yet

- History: The Origin of Kho-KhotheDocument17 pagesHistory: The Origin of Kho-KhotheIndrani BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- BILBAO-P.E 203 (Individual Reporting)Document21 pagesBILBAO-P.E 203 (Individual Reporting)Arnny BilbaoNo ratings yet

- Basketball Program ProposalDocument5 pagesBasketball Program Proposalned harris50% (2)

- Skedina 8 9Document5 pagesSkedina 8 9Elton XhepaNo ratings yet

- Disability in SportDocument10 pagesDisability in SportAiham AltayehNo ratings yet

- Coaching Combination Play The X Combination Pattern and Warm UpDocument4 pagesCoaching Combination Play The X Combination Pattern and Warm UpTabarro Avispon TocadoNo ratings yet

- M 3 UDocument3,247 pagesM 3 Uvebofek260No ratings yet

- The FIFA World CupDocument2 pagesThe FIFA World Cupfish manNo ratings yet

- Galacticos Football Tier PlayersDocument192 pagesGalacticos Football Tier PlayersDumitruGubaNo ratings yet

- European Soccer Betting Guide For BeginnersDocument3 pagesEuropean Soccer Betting Guide For Beginnersfindtheedge75% (8)

- Eagles-Browns Media Notes (Eagles)Document209 pagesEagles-Browns Media Notes (Eagles)TheOBRNo ratings yet

- Sepak TakrawDocument40 pagesSepak Takrawzoie abonalNo ratings yet

- Sports Day 2019-20Document6 pagesSports Day 2019-20ASHOK NAGARNo ratings yet

- Bowler GoalerDocument1 pageBowler GoalerlyanglarhaltzNo ratings yet

- PE G11 Single Dual Sports: Table TennisDocument22 pagesPE G11 Single Dual Sports: Table TennisRam KuizonNo ratings yet

- Pivot TablesDocument9 pagesPivot TablesVaishnavi ReddyNo ratings yet

- All India Football Federation Vs Rahul Mehra On 21 July 2022Document4 pagesAll India Football Federation Vs Rahul Mehra On 21 July 2022Prem PanickerNo ratings yet

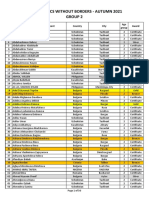

- Autumn2021 Age Group 2Document56 pagesAutumn2021 Age Group 2Di YungNo ratings yet

- Acc332 Test 9Document4 pagesAcc332 Test 9hjd75w46No ratings yet

- Blood Bowl Compendium 2Document53 pagesBlood Bowl Compendium 2PsyKo Tine100% (1)

- Farb 2022Document238 pagesFarb 2022jonNo ratings yet

- Match AnalysisDocument42 pagesMatch AnalysisDao Anh VuNo ratings yet

- Advantages of The Shield PuntDocument3 pagesAdvantages of The Shield Puntgmagic45032No ratings yet

- Coverdale Trinity High SchoolDocument4 pagesCoverdale Trinity High SchoolCoach BrownNo ratings yet