Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Black Economic Empowerment, Legitimacy

Black Economic Empowerment, Legitimacy

Uploaded by

Dr.Hira EmanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Black Economic Empowerment, Legitimacy

Black Economic Empowerment, Legitimacy

Uploaded by

Dr.Hira EmanCopyright:

Available Formats

Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

S. The Authors J.Finance Originalcompilation 2008 AFAANZ XXX Journal F. Cahan, 1467-629X 0810-5391 Accounting C. ACFI Article Oxford, UK and van Ltd Blackwell Publishing Staden

Black economic empowerment, legitimacy and the value added statement: evidence from post-apartheid South Africa

Steven F. Cahan, Chris J. van Staden

Department of Accounting and Finance, University of Auckland Business School, Auckland, 1010, New Zealand

Abstract We examine why companies in South Africa voluntarily provide a value added statement (VAS). The VAS can be used by management to communicate with employees and thereby establish a record of legitimacy. Since we want to establish if the VAS is used to establish symbolic or substantive legitimacy, we examine whether production of a VAS is associated with actual performance in labour-related areas. To measure labour-related performance, we use an independent Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) rating. We nd that BEE performance is signicantly and positively related to the voluntary publication of a VAS. Our results suggest that BEE performance and disclosure of a VAS are two elements of a strategy used by South African companies to establish their substantive legitimacy with labour. Key words: Labour relations; Accounting disclosures; Substantive legitimacy; Black economic empowerment; South Africa JEL classication: M41 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-629x.2008.00280.x

1. Introduction and motivation As nancial reporting becomes increasingly harmonized at a global level, the continued voluntary disclosure of a value added statement (VAS) by many

We thank Jayne Godfrey, Michael Keenan, Joanne Locke, Rachel Morley, Dean Neu, Deryl Northcott, Hector Perera, Jilnaught Wong, and participants at the 2005 Auckland Region Accounting Conference for their helpful comments. We also thank the participants and commentators at the 2006 Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Accounting Conference in Cardiff, the 2006 Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand Annual Conference in Wellington, and the 2007 American Accounting Association Conference in Chicago. Received 14 May 2008; accepted 26 June 2008 by Ian Zimmer (Deputy Editor).

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

38

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

South African companies remains an accounting oddity. The VAS is a supplemental statement that shows the value added in production and how that value is distributed among the companys various stakeholder groups. Historically, the VAS has been produced on a widespread basis in only a few instances, most notably in the UK in the late 1940s/early 1950s and 1970s (e.g. Burchell et al., 1985) and more recently in South Africa (e.g. Van Staden, 2003). Both Burchell et al. (1985) and Van Staden (2003) nd that increased production of the VAS coincided with the ascendancy of labour in the UK and South Africa, respectively. This suggests that companies use the VAS to establish or reinforce their legitimacy with labour.1 Less clear is whether companies use the VAS to establish substantive or symbolic legitimacy. Based on the literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR), under the symbolic approach, [r]ather than actually change its ways, the organization might simply portray or symbolically manage them so as to appear consistent with social values and expectations (Ashforth and Gibbs, 1990, p. 180). Therefore, a company with poor labour relations or practices might provide a VAS because its competitors and other companies are providing the VAS. In contrast, the substantive approach involves real, material change in organizational goals, structures, and processes or institutionalized practices (Ashforth and Gibbs, 1990, p. 178). Under the substantive view, only companies that actually have good performance in labour-related areas will have incentives to disclose a VAS. Of course, it is often not easy to distinguish between these two types of legitimacy because; to do so requires a credible measure of good labour performance. In the present study, we use the companys performance in the area of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) as a measure of labour performance. We view BEE practices as being critically important for South African companies because of the countrys past and continuing racial inequities. In that context, a companys ability to promote the employment of black South Africans and to improve their chances for advancement will be central in establishing legitimacy with labour (who are largely non-white). We examine whether companies that are relatively more progressive in their BEE practices are more likely to publish a VAS. A signicant positive relation between substantive labour performance and publication of a VAS would suggest that the VAS is part of a strategy being used by South African companies to establish substantive legitimacy with labour. A negative or no relation between the BEE ratings and disclosure of a VAS would suggest that companies use the

We do not believe that the VAS is the only mechanism used to establish legitimacy, nor is it our intention to identify all the mechanisms that a company might use to establish legitimacy with labour. As accounting researchers, we are interested in whether the VAS, which is an accounting-related disclosure, is one mechanism that companies use to establish substantive legitimacy with labour.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

39

VAS as part of an effort to establish symbolic legitimacy or that the publication of the VAS is motivated by factors unrelated to labour performance. Our results indicate that, ceteris paribus, BEE performance is signicantly and positively related to the production of a VAS. This indicates that production of a VAS is correlated with actual BEE performance. Our study makes two main contributions to the literature. First, we add to the very limited body of research on the VAS. Although both Burchell et al. (1985) and Van Staden (2003) link the production of the VAS to the ascendancy of labour at the country level, neither study attempts to explain why the production of a VAS might differ between companies within a country. Furthermore, as noted before, publishing the VAS is a reporting oddity and examining the motives behind this is interesting in its own right. Second, and more generally, we also contribute to a broader literature on the relation between a companys CSR disclosures and its actual CSR performance. For example, Patten (2005) notes that environmental disclosures are often seen as misleading because the disclosures do not appear to accurately measure a companys environmental performance. On the other hand, Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004) nd a positive relation between good environmental performance and environmental disclosures. In the present study, we add to the general debate on CSR disclosures versus performance by focusing on an unusual voluntary disclosure (the VAS) and a unique context (i.e. post-apartheid South Africa). To our knowledge, we are also the rst study to examine the link between race-related labour practices and accounting disclosures. Although race-related issues are by no means absent from the accounting literature (e.g. Annisette, 2003; Bernardi et al., 2005), we are the rst to show an empirical association between a companys race-related labour performance and the type of accounting reports that it voluntarily provides. The paper starts with background on the VAS, followed by the theoretical background and an overview of the development of labour policies in South Africa. This is followed by a discussion of our method, data and results for our empirical analysis, and the nal section contains our conclusions. 2. Background on the value added statement The concept of value added was initially used in 1790 in the rst North American Census of Production (Gillchrist, 1970) and has since been adopted by most industrial nations in the calculation of gross national product. The accounting denition that is most often used in the VAS calculates value added as sales less the cost of bought in goods and services. Suojanen (1954) denes the rm as an enterprise or decision-making centre for the participants (i.e. the enterprise theory). He also suggests the value added concept for income measurement as a way for management to full its accounting duty to the various interest groups. This makes him one of the rst writers to suggest the value added concept in terms of accounting for the results of an enterprise. The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

40

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

The publication of the VAS has waxed and waned over the years. According to the literature, the publication of the statement originated in the UK: initially in the late 1940s/early 1950s and then again in the 1970s. The literature is not replete with many other examples of the publication of the VAS. There are some references to publication in Europe, Australia and New Zealand, but it would appear that after the second waning in the UK (early 1980s), the publication of the statement has nearly disappeared worldwide. In the USA, companies never showed an interest in publishing the statement.2 The incidence of South African companies publishing the VAS has increased over time with 43 per cent of industrial companies producing a statement in 1997 and we found that by 2002, 55 per cent (125 of 228) of companies listed in the industrial sector on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange (JSE) published a VAS. The stakeholders typically represented in the VAS includes employees as providers of labour, capital providers (both loan capital and equity capital), the government (apparently as provider of infrastructure), and the company itself in terms of the part of value added that is reinvested. Burchell et al. (1985) indicate that value added could be regarded as a performance measure that puts employees on par with other interests in the enterprise. Gray et al. (1996) describes the VAS as a purportedly employee-related development, and employees are also often cited as the group of users of nancial information that should get the most use from the value added statement (e.g. Morley, 1978; Seal, 1987). Furthermore, IAS1 (International Accounting Standards Board, 2003) indicates that entities should also present VAS when employees are regarded to be an important user group. Van Staden (1998, 2003) nds strong evidence that management in South Africa see the VAS as having an important role in its relations with employees. For example, he nds that 89 per cent of managers responding to his survey use the VAS to communicate with employees. This was the most frequently cited reason for publishing a VAS in his study. Furthermore, managers also use the VAS to indicate social responsibility on the part of the company (83 per cent), to condition employee expectations regarding future wages (81 per cent), to communicate with uninitiated and less sophisticated users (81 per cent), and to facilitate wage negotiation and collective bargaining (80 per cent). Each of these reasons can be linked, directly or indirectly, to employees or to the companys role as an employer. Stainbank (1992) reports, in another South African study, that the value added statement is mainly used for employee communication (96 per cent) and wage negotiations (74 per cent).

The non-publication of the statement did not seem to deter US researchers from doing research on the accounting concept of value added since value added can usually be calculated from information published by the companies (see e.g. Riahi-Belkaoui, 1996; Bao and Bao, 1996).

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

41

Therefore, the work of Van Staden (1998, 2003) and Stainbank (1992) provide evidence that the VAS can be viewed as an employee-related development in the context of South Africa. However, this raises a related question: Given its usefulness to employees, why is it that not all South African companies provide a VAS? 3. Theoretical background A review of the literature on the VAS found a large number of articles, books and research reports published since 1954, when Suojanen (1954) wrote the article linking the VAS with the enterprise theory. However, Burchell et al. (1985) provide the rst and probably most comprehensive attempt to explain the theoretical motivation behind the interest in publishing the VAS, a statement that has never been required by statute or governed by accounting standards in any country. 3.1. The theory of Burchell et al. (1985) Burchell et al. (1985) aim to describe and analyse the relationship between accounting change and social change, as highlighted by the value added event in the UK. They describe three arenas (or complexes of issues, institutions, bodies of knowledge, practices and actions) that intersected in the 1970s to form a constellation with value added as an important element. In their view, this constellation explains the sudden upsurge of interest in the VAS in the UK in the 1970s. The three arenas that were identied are: the threat of government intervention in the standard setting process, macro-economic management under conditions of full employment, and industrial relations that were dominated by powerful trade unions and a growing acceptance of industrial democracy. Van Staden (2003) applies the framework of Burchell et al. (1985) to the South African situation and concluded that two of the three arenas were present in South Africa. These are the arena dealing with macro-economic management (although in the South African situation this was related to job creation rather than productivity growth) and the arena dealing with industrial relations (the impact of powerful trade unions). Van Staden relates these issues to the theories of political economy and concludes that the desire to gain legitimacy from a new set of powerful stakeholders provide a plausible explanation for the sustained publication of the statement in South Africa.3

3 De Villiers and Van Staden (2006) also observe legitimating behaviour when South African companies rst published more environmental information and then less when they realized that the priorities of the ANC government were job creation and equitable employment, and not environmental.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

42

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

The theory of Burchell et al. (1985) is very useful for explaining why the VAS has appeared for periods in certain countries, but it does not explain why, within a country, some companies disclose a VAS while others do not. To answer this question, we draw on organizational legitimacy theory. 3.2. Organizational legitimacy theory Although organizational legitimacy suggests that an organization should be operating within the norms and expectations of the society within which it operates to be regarded as legitimate, achieving legitimacy is a multifaceted process. Strategic organizational legitimacy views legitimacy as a resource that management can deploy or use to obtain societal support, making legitimacy management heavily dependent on communication between the organization and its various audiences (Suchman, 1995). Organizational legitimacy represents the reaction of observers to the organization as they see it (Suchman, 1995). In this regard Barnett (2007, p. 800) suggests that trust arises and relationships improve as stakeholders observe a rms CSR activities, not as a consequence of a rms use of direct inuence tactics to capture their favour. Barnett suggests that the ability of the company to improve stakeholder relations through CSR depends on prior relationships and that stakeholders base their assessment of new information regarding the companys CSR on their prior knowledge. In the accounting literature, legitimacy theory is often used to explain why companies are publishing voluntary social and environmental information, as this goes beyond the information that is legally required to be published. The literature is replete with studies dening and describing organizational legitimacy and how (voluntary) disclosures are generally used to achieve legitimacy (e.g. Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975; Lindblom, 1994; Deegan and Rankin, 1996; Milne and Patten, 2002). Disclosures are necessary to demonstrate legitimacy, otherwise a legitimate organization might face a legitimacy threat if its stakeholders are not aware that it is operating within their norms and expectations (Newson and Deegan, 2002). Various strategies can be used to obtain legitimacy (Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975; Lindblom, 1994). These strategies range from changing organizational goals, methods and outputs (substantive) to managing and changing perceptions about the companys goals, methods and outputs (symbolic). In this way the process of legitimization can therefore be symbolic or substantive (Ashforth and Gibbs, 1990). Several empirical studies nd that companies publish more environmental information in reaction to increased environmental exposures or some environmental event (see e.g. Patten, 1992, 2000; Deegan and Rankin, 1996). Although the results of these studies support legitimacy theory, some researchers (see e.g. Neu et al., 1998; Patten, 2005) point out that it is not possible to know which of the legitimacy strategies the companies are following; that is, are they adapting their outputs, goals and methods to conform with societys expectations (substantive legitimacy) or are they instead just using disclosures to project an The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

43

image of being legitimate (symbolic legitimacy)? Campbell (2007, p. 950) suggests that it is important to distinguish between the rhetoric of socially responsible corporate behaviour and substantive action. Therefore, based on the environmental disclosure literature, whether companies use voluntary disclosures to establish substantive or symbolic legitimacy is unclear, but nevertheless important to determine. South African companies (like all companies) need to be regarded as legitimate by their stakeholders, particularly the most powerful stakeholders. As we will show, in South Africa the most powerful stakeholder is (and was since the mid1980s) labour and their representatives, being the powerful labour unions and the African National Congress (ANC) labour coalition government. Analogous to studies that relate environmental disclosure to environmental performance, we examine whether disclosure of a VAS is related to a companys substantive labour performance. However, our tests are inherently more powerful than prior studies that examine CSR disclosures because, in those studies, the relevant stakeholder often has little or marginal power (e.g. green political parties, conservation groups). As we discuss in the next section, labours power and inuence in South Africa is huge. This creates a setting in which South African companies will have substantial incentives to establish legitimacy in the eyes of labour.4 However, in line with Barnett (2007), stakeholders of South African companies will only regard labour initiatives as credible from companies that are making substantive progress with labour. In our later empirical analysis, we test this by examining whether companies with good labour relations (which we proxy using BEE performance) are more likely to produce a VAS. As good labour relations could manifest itself in the publication of the VAS and progress on the BEE measures, we are not suggesting causality; rather, we are reporting on associations between these. 4. The South African labour situation In this section, we substantiate our claim of labours huge power and inuence in South Africa by providing an overview of the historical development of the labour policies of the ANC, the traditional party of the black majority and the current ruling party of South Africa.5

Although we expect that the need to ensure substantive legitimacy will motivate companies to disclose a VAS, we stress that we are not attempting to identify labours legitimate or fair share of the value added. Estimating this amount is probably not possible in any case, but more importantly, labour and management will always have different views on what is a legitimate share. In our denition of legitimacy (borrowed from Suchman, 1995), legitimacy involves being more meaningful, more predictable, and more trustworthy. An employer can exhibit these qualities even if it does not always pay or give the employees everything that they want.

5 Catchpowle and Cooper (1999), Van Staden (2003) and De Villiers and Van Staden (2006) provide comprehensive reviews of the social and economic backdrop in South Africa.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

44

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

From the 1940s, the ANC opposed capitalism and private enterprise. It had (and still has) strong alliances with the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) (the largest trade union movement in South Africa). The communist party was obviously anticapitalism, and COSATU was antiprivate enterprise in that they believed that their members would be better off in nationalized (state) enterprises. Before its un-banning in 1990, one recurring theme of the ANC was that apartheid, inequality and capitalism were integrally related and that state intervention was therefore needed to create a more equitable and just economic system (Catchpowle and Cooper, 1999). Williams and Taylor (2000, p. 24) describe the ANCs economic policy for most of the struggle as a mixture of dirigisme and socialist reform of the economy via nationalization of the mines, banks and monopoly industries. The ANC, in its efforts to bring about majority rule in South Africa, called for economic sanctions and disinvestment by the international community in order to force change by economic isolation. This contributed to an economic slowdown in South Africa which no doubt helped to usher in the new dispensation in South Africa. Furthermore, even after its un-banning, the ANC often talked about nationalization as a means of obtaining capital for redistribution. As a result, business continued to view the ANC as antibusiness (anticapital) and pro-labour, and during the 1980s when it became clear that the ANC would be the next government, business feared the result.6 However, when the ANC took over the government in 1994, it changed its economic policies and embraced the free market principles that were operating in South Africa because realistically there was no alternative as it would have be impossible for the ANC to develop a socioeconomic restructuring program that was independent of the existing worldwide capitalist system (Catchpowle and Cooper, 1999; Williams and Taylor, 2000). Although many supporters of the ANC (including the SACP/COSATU alliance) were shocked by this shift in ideology, the ANC continued to push for labour-related reforms, and as a result, the labour market became much regulated. In addition, the government adopted the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) program in order to encourage the employment of black people at all levels of business, and also to encourage black entrepreneurs and black business ownership. Since then, the labour unions continue to wield a sizeable inuence. There are signs that their alliance with the ANC is not so strong anymore. If the ANC/ COSATU/SACP alliance breaks up, and COSATO and the SACP form a new alliance and can mobilize the support of the unemployed (currently more than

6 It is important to note that even though the ANC was un-banned during 1990 and became the elected government in 1994, business knew since the mid-1980s already that the government was going to change and that the disenfranchised was going to become the new government or strongly represented by the new government.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

45

40 per cent7), the ANC might lose power and a new labour government might form. Even if this does not occur, currently there is constant friction with the COSATU movement concerned about wage levels versus prots and executive salaries.8 What this episode suggests is that business still sees powerful labour as a major threat in South Africa and has incentives to establish and maintain their legitimacy in the eyes of labour. 5. The BEE measures and rating We use an independent rating of BEE performance in South Africa as a measure of a companys labour practices, as empowerment of non-white people is one of the most important goals in South Africa. The BEE ratings that we use in this study have been compiled by Empowerdex, an economic empowerment rating agency in South Africa.9 We use Empowerdexs 2004 ratings that, to our knowledge, were the rst comprehensive rating of South African companies based on BEE performance. Their methodology is available on their website and includes establishing benchmarks using public available information as well as additional information supplied by companies on request (Empowerdex, 2004). Empowerdex calculates a total BEE score (out of 100) based on seven subcategories (each out of 100) and then rank the companies according to their BEE score. These categories indicate progress in advancing the interests of black (non-white) people in the following areas: ownership in the company, management (directors and executive directors), employment equity (including top-management), skills development, afrmative procurement, enterprise development (developing black business partners, including suppliers), and corporate social investment (being investment towards education and community development).

7 The very high unemployment rate in South Africa also raises concern about the current economic policies of the ANC (e.g. Williams and Taylor (2000, p. 37) indicate that the scal policies have constructed an economy which goes nowhere in terms of conditions of life for the greater majority of people) and the appropriateness of the ANCs pro-business policies. 8

In a more recent development, Jacob Zuma has been elected as leader of the ANC in December 2007 and it is generally believed that he will succeed Thabo Mbeki as president in 2009. Zuma has the support of the labour unions and is likely to be antibusiness. The New Zealand Herald reports as follows: uncertainty over his policies and his strong left-wing backing have caused jitters among many investors . . . [m]arkets fear Zuma could reverse Mbekis centrist policies, which have fuelled the longest period of growth in Africas economic powerhouse (Simao, 2007).

Empowerdex is an independent economic empowerment rating and research agency. It was founded in 2002 by Vuyo Jack and Chia-Chao Wu and became involved in the sphere of BEE research with the release of South Africas rst empowerment-based survey. Empowerdex is funded through subscriptions and claims to have no political agenda other than to reveal progress towards broad-based BEE in South Africa.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

46

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

We used a report published by the Financial Mail in 2004 (Top Empowerment Companies), which reported the top 200 companies in terms of BEE (F.M., 2004). This list has been compiled by Empowerdex after they benchmarked all 362 Johannesburg Securities Exchange-listed companies. We have several comments about the BEE program and BEE ratings. First, compliance with the BEE policies was not (and is still not) compulsory. South African companies can respond in some, none, or all of the seven specic areas identied above. Therefore, companies that are making progress on BEE objectives are doing so because they want to rather than because they are forced to do so.10 Second, we focus on the rst release of BEE ratings in 2004. In other words, the ratings will reect the progress of the rst movers or early adopters of BEE practices. The companies that rate highly in this round will likely be the most innovative and progressive employers. Third, the BEE ratings are not easily exaggerated or falsied. The ratings are determined by an independent rating organization based on publicly available information. Therefore, to get a high rating, the company must be taking real actions, and companies cannot manage the rating gures in the way they can manage their earnings.11 Together, these points give us condence that the BEE ratings are measuring the companys substantive progress in the BEE areas. Said differently, they are not purely cosmetic or symbolic measures. Equally important, the BEE ratings are a measure of relative, not absolute, BEE progress. Therefore, higher ratings suggest the company is doing well compared to other South African companies. It does not mean that the company is a perfect or ideal employer. Furthermore, given South Africas apartheid past where black people were discriminated against, we expect that most companies would be starting from a low base in terms of their BEE practices. Hence, on average, we expect the South African companies to rate lowly in the initial BEE ratings in 2004. 6. Method and data The purpose of our analysis is to examine whether the publication of a VAS is statistically related to a companys BEE rating where the BEE rating is a

For example, in 2002, companies did not have to comply with BEE policies to be awarded government contracts. This is still the case in 2006.

11

10

Although there could be a view that companies are just making symbolic appointments to executive positions, in the South African context where BEE is seen as such an important issue, there is not really much scope to do it at this level as these individuals will object to be treated in this way and will have the support of the majority view. In addition, these individuals are very highly remunerated and as Campbell (2007) indicates, committing signicant resources to an issue is an indication that it is taken seriously.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

47

proxy for the companys actual labour progress.12 In our rating system, good BEE performers have high BEE ratings; therefore, a positive association between the BEE rating and VAS disclosure would support the contention that the VAS is being used as part of a strategy to establish substantive legitimacy with labour. For these analyses, our dependent variable is a binary variable that is coded 1 if the company provided a VAS and 0 otherwise. We label this variable VASDUM. Because our dependent variable is dichotomous, we use logistic regression in our multivariate tests. We use two different specications of the BEE scores that are provided by the Financial Mail. We use the total BEE score (BEESCORE), which is based on seven subcategories. For BEESCORE, a higher value indicates better BEE performance.13 Second, we use the score for each of the separate BEE subcategories. The subcategories cover the following areas (variable labels in parentheses): ownership (BEE_OWN), management (BEE_MAN), employment equity (BEE_EE), skill development (BEE_SKILL), afrmative procurement (BEE_AFFIRM), enterprise development (BEE_ENTRPSE) and corporate social investment (BEE_SOC). For the individual categories, our expectation is that it should be easier for companies to make progress on those dimensions that are rmspecic. For example, BEE_AFFIRM, BEE_ENTRPSE and BEE_SOC involve the participation and cooperation of organizations outside the company, whereas BEE_OWN, BEE_MAN, BEE_EE and BEE_SKILL focus on the company itself and, hence, are likely to be easier to control. However, because companies might be motivated to produce a VAS for a variety of reasons, we include additional variables to represent other stakeholderrelated demands. Therefore, in our multivariate tests, we include control variables for shareholder, creditor and government demands. Since all prior research examining motives for disclosing a VAS has been qualitative, the selection of our control variables is based on intuition and the broader accounting choice literature. For example, some of our control variables are motivated by costly contracting theory. However, as Carpenter and Feroz (2001) and Chalmers and Godfrey (2004) point out, economic theories like costly contracting theory should be viewed as complementary to legitimacy theory. We represent shareholder demands using the number of analysts following the company at the end of the nancial year (ANALYST). This variable is a proxy for the degree of investor interest in the company. We expect that where

Our tests do not require that we use BEE ratings but require a measure of substantive labour performance. However, very few measures of substantive labour performance are available. Furthermore, given the context where race-related labour issues are paramount, the BEE ratings are attractive both from a theoretical and practical standpoint.

13 We also run our tests using the rank of the BEE score (i.e. an ordinal rather than interval measure) and obtain qualitatively similar results.

12

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

48

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

there is greater investor interest, there will be greater demand for disclosures, and this could include demand for a VAS. Therefore, we expect the coefcients for ANALYST to be positive. To capture the demands of creditors, we use the ratio of long-term liabilities to total assets (LEVRGE). While creditors have xed claims against the company, they want to know whether their funds have been used to fund wealth transfers to other stakeholders, and the VAS can provide some information on that (since the VAS shows how the value added is divided among the different stakeholder groups). Therefore, LEVGR should have a positive coefcient. Furthermore, we expect that companies that are large will be relatively more important from the governments perspective which is consistent with the political cost hypothesis (e.g. Watts and Zimmerman, 1978). As a result, the government will want to monitor those companies more closely and, in particular, will be concerned about how those companies treat the competing stakeholder groups such as labour. We use the natural log of the market value of equity to measure rm size (FIRMSIZE), and we expect FIRMSIZE to be positively related to disclosure of a VAS.14 Finally, since more protable companies and fast growing companies have been shown to provide more disclosure (e.g. Lang and Lundholm, 1993; Barnett, 2007; Campbell, 2007), we include the companys return on assets (ROA) (i.e. net income scaled by total assets) and year-to-year growth in sales (SGROW) as additional control variables.15 Therefore, for our multivariate tests, we estimate the following model using logistic regression: VASDUM = 0 + 1BEE variable + 2ANALYST + 3LEVRGE + 4FIRMSIZE + 5ROA + 6SGROW, where the BEE variable can be BEESCORE or the score for an individual BEE subcategory. In this model, we use the coefcient of the BEE variable (1) to test the association between the BEE rating and disclosure of a VAS. If 1 is

Another reason to control for rm size is to control for the inuence of government contracts. Although it is not a legal requirement that companies comply with BEE policies to gain government contracts, companies might perceive that it is important. If so, large companies, which are the most likely to gain government contracts, might pursue progressive BEE policies to gain these contracts. Therefore, including rm size controls for this alternative explanation.

15 Campbell (2007) suggests that companies that have a weaker nancial performance are less likely to engage in CSR than those with stronger nancial performance, while Barnett (2007) suggests that doing too well nancially can lead to a stakeholder perception the company is not doing enough CSR. The company might therefore publish additional information to show that all stakeholders are still treated fairly despite the stronger nancial performance. The VAS can conceivably be used for this.

14

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

49

positive and signicant, this would indicate companies with higher BEE ratings (i.e. more substantive labour progress) are more likely to provide a VAS. This would be consistent with the view that the VAS is a part of a strategy to gain or maintain substantive legitimacy and establish a history or prior knowledge of being a trustworthy company. On the other hand, if 1 is insignicant or negative and signicant, this would indicate no relation between BEE performance and the VAS or a negative relation between BEE performance and the VAS (i.e. in the latter case, poor BEE performers provide a VAS). This evidence would be consistent with the view that the VAS is used to mislead employees or to create symbolic legitimacy. We collect our nancial data from the McGregor BFA database, a commercial database with nancial data of all South African listed companies. We use the 2002 data for our analysis and include all 228 companies listed on the industrial sector of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in our sample.16 After eliminating those with incomplete data, we have complete data for 186 South African companies, 118 that publish and 68 that do not publish the VAS. We nd that the companies publishing the VAS are spread across the spectrum of industries in our sample. We nd at least one disclosing company in each of the 22 industries represented in our sample, and in 18 of the 22 industries, we nd at least half of the companies provide a VAS. We collect the BEE scores and rankings from the website of the Financial Mail (South Africas leading business periodical) (www.nancialmail.co.za). Because the Financial Mail website only reports the top 200 companies in terms of BEE performance, if a company is not reported, we give this company a zero for BEESCORE (and for each subcategory) and we give it a BEE rank of 200 (which is the lowest rank for the 200 ranked companies). This seems reasonable since the company ranked 200 had an overall BEE score of 4.47 (out of 100) and scored zero on several of the subcategories. Of 186 sample rms, 73 or 39.2 per cent are not ranked in the top 200.17

16 We use 2002 data since the 2004 BEE ratings would have been based on BEE performance prior to the end of 2004. Moreover, we expect that a companys BEE performance would reect the companys long-term efforts in the BEE area. That is, we do not expect that a good performer would have become a good performer overnight. Rather, it would reect the companys long-term strategy and commitment to improve its labour relations with black employees. Therefore, even though released in 2004, the BEE rating can be viewed as a measure of labour progress over a historical period that includes 2002. We also use the 2002 period because we want a period before the BEE ratings were available. It is possible that companies might see the BEE ratings as a substitute for disclosure of a VAS. In that case, a good BEE performer might have less incentive to disclose a VAS after the BEE ratings became available. 17 We nd qualitatively similar results when the non-ranked rms are excluded from the analysis.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

50

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

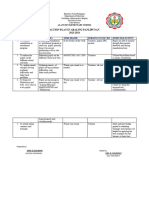

7. Results Panel A of Table 1 provides descriptive data for the independent variables. The mean (median) BEESCORE is 11.690 (7.150) with a range from 0 to 55.320. Because the index has a theoretical maximum of 100, the averages suggest that South African companies are starting at zero in terms of BEE, which is not surprising given South Africas past where black people were discriminated against in the workplace. From our perspective, we are interested in relative performance (rather than absolute performance) so this only requires that we have dispersion in our BEE measures. For the seven subcategory scores, the highest mean is for BEE_MGT (15.061). BEE_MGT reects the companys performance in terms of having black directors and managers.18 The means for BEE_OWN, which measures black ownership, and BEE_SKILL, which measures the implementation of skills development programs, are also relatively high (i.e. 14.409 and 14.413, respectively). The lowest mean is for BEE_ENTRPSE (7.000). BEE_ENTRPSE reects the companys involvement in black enterprise development programs. Consistent with our expectations, the companies perform better on the four rm-specic dimensions. In addition, the median for ve of the seven categories (all except BEE_OWN and BEE_MGT) is zero, which reinforces the view that the South African companies are starting from a zero base in terms of BEE performance. However, it is also worth noting that some companies are extremely progressive. For example, the top score for BEE_MGT, BEE_SKILL and BEE_SOC is 100 (the highest score possible). Even BEE_EE and BEE_AFFIRM, which have the lowest high scores, have top scores of 77.8 and 71.5, respectively. Therefore, it is clear that some companies have made signicant progress on these individual dimensions of BEE. Panel B of Table 1 provides a breakdown of the sample by industry. The largest industry concentrations are in retail (25 rms) and software (24 rms). However, overall the sample captures rms from a diverse set of industry sectors. Table 2 provides univariate tests that examine the relation between BEE performance and the VAS. Specically, we compare the BEE variables between the VAS providers (118 companies) and the VAS non-providers (68 companies). Using the overall score, the mean for BEESCORE for the VAS providers is 15.395 (column 1) while the mean for the non-providers is 5.261 (column 2). This difference is statistically signicant at the 0.01 level based on both a parametric

The BEE measures on which progress were made by the more progressive companies in our sample are those requiring a (substantial) commitment of resources (large salaries for black managers/top management and directors). This indicates a substantive commitment and distinguishes it from symbolic actions which most often manifest in mere rhetoric in nancial reports, press releases and other releases.

18

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and industry breakdown for 186 South African companies Panel A: Descriptive statistics Variable Labour variables BEESCORE By subcategory BEE_OWN BEE_MGT BEE_EE BEE_SKILL BEE_AFFIRM BEE_ENTRPSE BEE_SOC Control variables ANALYST LEVRGE FIRMSIZE ROA SGROW Mean SD Minimum Median

51

Maximum

11.690 14.409 15.061 11.522 14.413 8.700 7.000 8.209 6.591 0.118 17.077 0.054 0.183

13.894 19.814 23.142 19.902 22.992 16.472 15.670 21.659 3.334 0.135 2.346 0.319 0.485

0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 2.000 0.000 10.860 2.460 0.860

7.150 4.800 3.250 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 9.000 0.077 16.999 0.076 0.155

55.320 96.200 100.000 77.800 100.000 71.500 85.000 100.000 9.000 0.660 23.340 2.130 4.340

Panel B: Industry breakdown Industry Auto Beverage Building Chemicals Diverse Electric Engineering Food Forestry Health Household N 6 2 14 5 4 9 5 14 3 5 10 Industry Information technology Leisure Media Oil and gas Pharmaceuticals Retail Software Steel Support Telecom Transportation N 4 9 11 3 2 25 24 2 15 1 11

Panel A provides descriptive statistics for BEESCORE, the subcomponents of BEESCORE, and the control variables. BEESCORE is a measure of black economic empowerment and is based on seven subcategories: ownership (BEE_OWN), management (BEE_MAN), employment equity (BEE_EE), skill development (BEE_SKILL), afrmative procurement (BEE_AFFIRM), enterprise development (BEE_ENTRPSE), and corporate social investment (BEE_SOC). ANALYST is the number of analysts following the company at the end of the nancial year. LEVRGE is the ratio of long-term liabilities to total assets. FIRMSIZE is the natural log of the market value of equity. ROA is net income scaled by total assets. SGROW is the year-to-year growth in sales. Panel B provides the number of rms by industry. SD, standard deviation.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

52

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

Table 2 Univariate tests for differences in Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) scores between value added statement (VAS) providers (118 companies) and VAS non-providers (68 companies) VAS providers Mean (SD) 15.395 (14.150) 18.636 18.858 14.829 19.589 11.341 9.423 11.603 (19.914) (23.182) (21.531) (23.573) (17.942) (17.895) (25.717) VAS non-providers Mean (SD) 5.261 (10.828) 7.075 8.472 5.784 5.434 4.115 2.794 2.318 (17.478) (21.700) (15.216) (15.363) (12.388) (9.518) (9.212)

Variable BEESCORE By BEE subcategory BEE_OWN BEE_MGT BEE_EE BEE_SKILL BEE_AFFIRM BEE_ENTRPSE BEE_SOC

t-statistic 5.105*** 3.983*** 3.011*** 3.051*** 4.436*** 2.940*** 2.831*** 2.870***

Wilcoxon Z 5.984*** 5.473*** 4.505*** 3.690*** 5.556*** 3.345*** 3.991*** 3.166***

*** indicates signicance at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). This table provides the results of tests of differences between companies that did and did not voluntarily disclose a VAS. BEESCORE is a measure of BEE and is based on seven subcategories: ownership (BEE_OWN), management (BEE_MAN), employment equity (BEE_EE), skill development (BEE_SKILL), afrmative procurement (BEE_AFFIRM), enterprise development (BEE_ENTRPSE), and corporate social investment (BEE_SOC).

Table 3 Pearson correlation matrix for BEESCORE and control variables BEESCORE BEESCORE ANALYST LEVRGE FIRMSIZE ROA SGROW ANALYST LEVRGE FIRMSIZE ROA

0.061 0.057 0.515*** 0.101 0.080

0.021 0.270*** 0.156** 0.034

0.105 0.032 0.007

0.245*** 0.091

0.034

** and *** indicate signicance at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels (two-tailed), respectively. This table provides Pearson correlation coefcients for BEESCORE and the control variables. BEESCORE is a measure of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). ANALYST is the number of analysts following the company at the end of the nancial year. LEVRGE is the ratio of long-term liabilities to total assets. FIRMSIZE is the natural log of the market value of equity. ROA is net income scaled by total assets. SGROW is the year-to-year growth in sales.

t-test and non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Together, these results indicate that publishing the VAS is positively and signicantly related to BEE performance. The results for the seven subcategory scores are similar. In each case, the providers (column 1) have higher subcategory scores than the non-providers (column 2), and in each case, the difference is signicant at the 0.01 level based The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

53

on a t-test or Wilcoxon test. Overall, Table 2 shows that BEE performance and disclosure of a VAS are positively related on a univariate basis, which supports the view that the VAS is part of a package used to establish substantive legitimacy. Table 3 provides the Pearson correlation matrix for the independent variables. The highest correlation is between BEESCORE and FIRMSIZE (r = 0.515). This conrms the need to control for rm size as BEESCORE could be proxying for a rm size effect. In other words, in our multivariate tests, we hold rm size constant in order to examine the incremental effect of BEESCORE when companies are the same size. In addition, FIRMSIZE is also signicantly correlated with ANALYSTS and ROA, indicating that for this sample of South African companies, large companies are followed by fewer analysts and are more protable. Table 4 contains the results for our main logistic regressions. We begin by estimating a benchmark model that includes all of our control variables but excludes our test variable (BEESCORE). In this model, we nd that disclosure of a VAS is signicantly related to rm size and protability as expected. On the other hand, contrary to our prior expectations, companies with higher leverage are less likely to disclose a VAS. The benchmark model has a Nagelkerke R2 of 23.8 per cent, which suggests that the control variables can explain 23.8 per cent of the variation in the decision to disclose the VAS across companies.19 In model 1A, we include BEESCORE. We nd that BEESCORE is positively related to VASDUM and is signicant at the 0.01 level. This indicates that the BEE rating has incremental explanatory above and beyond the control variables. Specically, holding the number of analysts, leverage, rm size, ROA, and sales growth constant, companies with high BEE scores are much more likely to disclose a VAS. The results for the control variables are consistent with the benchmark model (i.e. LEVRGE, FIRMSIZE and ROA are signicant). The Nagelkerke R2 for model 1A is 29.4 per cent, which represents a 23.5 per cent increase over the benchmark model. It is possible that industry is an omitted variable in that some industries might be more progressive in terms of BEE and might also be more likely to provide a VAS. Therefore, BEESCORE might be capturing industry trends rather than specic differences at the rm level. To control for a possible industry effect, we add 21 industry dummy variables to model 1B. We also show these results in Table 4, although for brevity, the coefcients for the industry dummy variables are unreported. In model 1B, BEESCORE remains positive and highly signicant after controlling for industry effects. For the control variables, FIRMSIZE and ROA are signicant with positive signs. Finally, the Nagelkerke R2 for model 1B is 50.5 per cent, which represents a 71.8 per cent increase over model 1A. This indicates that the industry variables have substantial explanatory

19 In logistic regression, the standard R2 cannot be computed. The Nagelkerke R2 is a pseudoR2 and can be interpreted similar to the R2 in ordinary least-squares regression.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

The Authors

54

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

Table 4 Estimated results from logistic regression of VASDUM on Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) score and other independent variables

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

Variables Labour variables BEESCORE REV/EMP Control variables ANALYST LEVRGE FIRMSIZE ROA SGROW Constant Industry dummies 2 log likelihood Nagelkerke R2

Expected sign

Benchmark model Coefcient (Wald statistic)

Model 1A Coefcient (Wald statistic)

Model 1B Coefcient (Wald statistic)

Model 2 Coefcient (Wald statistic)

0.053*** (7.475)

0.093*** (12.362)

0.067*** (5.727) 0.001** (2.803) 0.091 (1.136) 3.168* (2.206) 0.214* (2.128) 1.541* (2.557) 0.203 (0.150) 0.199 (0.004) Included 115.636 0.488

+ + + + +

0.012 (0.048) 2.324* (3.075) 0.381*** (19.674) 0.928* (1.673) 0.150 (0.197) 5.512*** (13.204) Excluded 208.675 0.238

0.023 (0.169) 2.372** (3.030) 0.232*** (5.596) 1.125** (2.761) 0.085 (0.062) 3.444** (4.288) Excluded 199.304 0.294

0.063 (0.848) 1.995 (1.493) 0.195** (2.852) 1.665** (2.761) 0.193 (0.179) 1.548 (0.486) Included 158.468 0.505

*, ** and *** indicate signicance at the 0.10, 0.05 and 0.01 levels (one-tailed), respectively. This table provides the logistic regression results. BEESCORE is a measure of BEE. ANALYST is the number of analysts following the company at the end of the nancial year. LEVRGE is the ratio of long-term liabilities to total assets. FIRMSIZE is the natural log of the market value of equity. ROA is net income scaled by total assets. SGROW is the year-to-year growth in sales. REV/EMP is labour intensity dened as revenue per employee measured on an annual basis.

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

55

power that is incremental to the variables already in the model. In other words, there are industry trends in terms of disclosure of the VAS. However, our results show that even after controlling for industry effects, companies with higher BEE scores are still more likely to disclose a VAS, a nding that is consistent with substantive legitimacy.20,21 To examine the sensitivity of the results to our choice of control variables, we estimate models 1A and 1B using alternative measures for shareholder, creditor and government demands since ANALYST, LEVRGE and FIRMSIZE might measure these constructs with noise. We use the average trading volume of shares during the year as an alternative measure for shareholder demands, the interest expense ratio (interest expense/sales) as an alternative measure for creditor demands, and the effective tax rate (taxes paid/pre-tax income) as an alternative measure for government demands. When these variables are used in place of ANALYST, LEVRGE and FIRMSIZE, BEESCORE remains positively and signicantly related to VASDUM at the 0.01 level in both models 1A and 1B (results untabulated). We also estimate models 1A and 1B with these variables included in addition to ANALYST, LEVRGE and FIRMSIZE. Our results (untabulated) are qualitatively unchanged. Although our previous results strongly suggest that BEE performance and disclosure of a VAS are related, an alternative explanation is that BEE performance could be a proxy for labour force intensity. Specically, companies that rely more heavily on labour have more incentives to improve their labour relations and BEE practices. Therefore, labour intensity could be an omitted variable in our earlier models; that is, disclosure of the VAS could be driven by labour intensity rather than BEE performance. To examine this possibility, we include a control for labour intensity in our models. We measure labour intensity using the revenue per employee measured on an annual basis (REV/EMP). Greater revenue or income per employee would indicate less labour intensity since fewer employees are required to generate each dollar of revenue or income. Table 4 provides these additional results. In model 2, which uses REV/EMP to control for labour intensity and BEESCORE to measure BEE performance, we nd that REV/EMP is signicantly associated with VASDUM, and REV/EMP has a negative coefcient. This indicates

In supplemental tests (unreported), we also estimate our logistic regression model using the BEE subcategory scores in place of BEESCORE. Because there are seven subcategory scores, we run seven separate models where we include one subcategory score in each model. The subcategory score is positive and signicant in ve of the seven models. This suggests that no one subcategory is driving our main results.

21

20

To address concerns that FIRMSIZE might not capture the governments interest in a South African context, we also estimate a model where we replace FIRMSIZE with the number of employees (WRKFORCE). Companies with larger work forces are likely to capture more political attention. When WRKFORCE is included, the coefcient for BEESCORE remains positive and signicant at the 0.01 level.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

56

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

that as labour intensity decreases (i.e. as REV/EMP increases), companies are less likely to provide a VAS as we would expect. However, after controlling for the effect of labour intensity, we nd that BEESCORE is still signicantly and positively related to VASDUM. This indicates that the effect of BEE performance is incremental to labour intensity and our ve other control variables.22 8. Conclusion We examine whether there is a statistical association between BEE performance and disclosure of a VAS. We nd that there is a positive association, indicating that companies with good labour performance are more likely to provide the VAS. This effect is incremental to the effects of analyst following, leverage, rm size, protability, sales growth and industry effects. Furthermore, we show that our results are not explained solely by differences in labour intensity. Overall, our results support the contention that the VAS is an element of a strategy to develop substantive legitimacy with labour. Our results conrm the Barnett (2007) contention that without a commitment to CSR and a history in the area, any attempt at legitimacy will probably be regarded as symbolic. Therefore, only companies that were serious about establishing a history of substantive legitimacy persisted with the disclosure of the VAS and they were also the rst movers when it came to BEE progress (before it was compulsory or necessary for government contracts). It shows that these were the companies that over time wanted to give a consistent message that they are concerned about labour/empowerment issues. Our results suggest that BEE performance and disclosure of a VAS are two elements of a strategy used by South African companies to establish their substantive legitimacy with labour. Like any research, our study has some limitations and these should be considered in the interpretation of the results. We do not take into account the content of the VAS as our focus is on the decision to disclose or not disclose the VAS. We acknowledge that analysing the content of the VAS could be a fruitful area for future research, but such a study would have to be limited to companies that actually publish a VAS, whereas our study focus on the decision to publish the statement. In addition, while we argue that the BEE measures are an indication of substantive progress in the labour area, it remains a possibility that the BEE ratings reect symbolic actions. However, in the context of South Africa where the majority of the population wants BEE to happen, it seems unlikely that business would be able to hold out against the wishes of the majority and that the symbolic appointees would not speak out.

22 We also estimate model 2 using the income generated per employee in place of REV/EMP. Our results for BEESCORE are consistent with Table 4.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

57

References

Al-Tuwaijri, S. A., T. E. Christensen, and K. E. Hughes II, 2004, The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: a simultaneous equations approach, Accounting, Organizations and Society 29, 447471. Annisette, M., 2003, The colour of accountancy: examining the salience of race in a professionalisation project, Accounting, Organizations and Society 28, 639674. Ashforth, B. E., and B. W. Gibbs, 1990, The double-edge of organizational legitimation, Organization Science 1, 177194. Bao, B., and D. Bao, 1996, The time series behavior and predictive-ability results of annual value added data, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 23, 449 460. Barnett, M. L., 2007, Stakeholder inuence capacity and the variability of nancial returns to corporate social responsibility, Academy of Management Review 32, 794816. Bernardi, R. A., D. F. Bean, and K. M. Weippert, 2005, Minority membership on boards of directors: the case for requiring pictures of boards in annual reports, Critical Perspectives on Accounting 16, 10191033. Burchell, S., C. Clubb, and A. G. Hopwood, 1985, Accounting in its social context: towards a history of value added in the United Kingdom, Accounting, Organizations and Society 10, 381413. Campbell, J. L., 2007, Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility, Academy of Management Review 32, 946 967. Carpenter, V., and E. Feroz, 2001, Institutional theory and accounting rule choice: an analysis of four US state governments decisions to adopt generally accepted accounting principles, Accounting, Organizations and Society 26, 565 596. Catchpowle, L., and C. Cooper, 1999, No escaping the nancial: the economic referent in South Africa, Critical Perspectives on Accounting 10, 711746. Chalmers, K., and J. M. Godfrey, 2004, Reputation costs: the impetus for voluntary derivative nancial instrument reporting, Accounting, Organizations and Society 29, 95 125. De Villiers, C. J., and C. J. Van Staden, 2006, Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimising effect? Evidence from Africa, Accounting, Organizations and Society 31, 763781. Deegan, C., and M. Rankin, 1996, Do Australian companies report environmental news objectively? An Analysis of environmental disclosures by rms prosecuted successfully by the Environmental Protection Authority, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 9, 50 67. Dowling, J., and J. Pfeffer, 1975, Organizational legitimacy: social values and organizational behaviour, Pacic Sociological Review 18, 122136. Empowerdex, 2004, How We Benchmark Empowerment [online; cited 19 November 2004]. Available: http://www.empowerdex.co.za/meth.htm. F. M., 2004, Top Empowerment Companies 2004 [online; cited 23 November 2004]. Available: http://free.nancialmail.co.za/projects/topbeecos/index.html. Gillchrist, R. R., 1970, Company appraisal and control by added value analysis, Certied Accountants Journal October, 573580. Gray, R., D. Owen, and C. Adams, 1996, Accounting and Accountability (Prentice Hall, London). International Accounting Standards Board, 2003, IAS 1: Presentation of Financial Statements (International Accounting Standards Board, London). Lang, M., and R. Lundholm, 1993, Cross-sectional determinants of analysts ratings of corporate disclosures, Journal of Accounting Research 31, 246 271. Lindblom, C. K., 1994, The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure, Paper presented at the Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, New York, April 1994.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

58

S. F. Cahan, C. J. van Staden /Accounting and Finance 49 (2009) 3758

Milne, M. J., and D. M. Patten, 2002, Securing organizational legitimacy. An experimental decision case examining the impact of environmental disclosures, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 15, 372 405. Morley, M. F., 1978, The Value Added Statement: A Review of Its Use in Corporate Reports (Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, Gee & Co. Publishers, London). Neu, D., H. Warsame, and K. Pedwell, 1998, Managing public impressions: environmental disclosures in annual reports, Accounting, Organizations and Society 23, 265282. Newson, M., and C. Deegan, 2002, Global expectations and their association with corporate social disclosure practices in Australia, Singapore, and South Korea, International Journal of Accounting 37, 183 213. Patten, D. M., 1992, Intra-industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaska oil spill: a note on Legitimacy Theory, Accounting, Organizations and Society 17, 471 475. Patten, D. M., 2000, Changing Superfund disclosure and its relation to the provision of other environmental information, Advances in Environmental Accounting and Management 1, 101121. Patten, D. M., 2005, The accuracy of nancial report projections of future environmental capital expenditures: a research note, Accounting, Organizations and Society 30, 457 468. Riahi-Belkaoui, A., 1996, Performance Results in Value Added Reporting (Quorum Books, Westport, CT). Seal, W. B., 1987, Value added and the theory of the rm: on mirages and the fallacy of decomposition, British Accounting Review 19, 145159. Simao, P., 2007, Zuma elected leader of South Africas ANC, The New Zealand Herald [online; cited 19 December 2007]. Available: http://www.nzherald.co.nz/section/2/ story.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=10483212. Stainbank, L., 1992, Value added reporting in South Africa, De Ratione 6, 4358. Suchman, M. C., 1995, Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches, Academy of Management Review 20, 571 610. Suojanen, W. W., 1954, Accounting theory and the large corporation, Accounting Review 29, 391398. Van Staden, C. J., 1998, The usefulness of the value added statement in South Africa, Managerial Finance 24, 4459. Van Staden, C. J., 2003, The relevance of theories of political economy to the understanding of nancial reporting in South Africa: the case of value added statements, Accounting Forum 27, 224 245. Watts, R. L., and J. L. Zimmerman, 1978, Towards a positive theory of the determinants of accounting standards, Accounting Review 53, 112 134. Williams, P., and I. Taylor, 2000, Neoliberalism and the political economy of the New South Africa, New Political Economy 5, 2139.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2009 AFAANZ

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- NOAA Diving ManualDocument520 pagesNOAA Diving Manualdasalomon100% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Adventuring Classes - A Fistful of Denarii PDFDocument52 pagesAdventuring Classes - A Fistful of Denarii PDFJohn Frangos100% (2)

- All Sons & Daughters - SongbookDocument26 pagesAll Sons & Daughters - SongbookJesseJ.CannonII100% (2)

- Domestic DisciplineDocument25 pagesDomestic DisciplinePastor David43% (7)

- JHCSC 2019 39124Document1 pageJHCSC 2019 39124Rajesh Dubey0% (1)

- Reading 1louis IVDocument6 pagesReading 1louis IVsamson610No ratings yet

- Adugna LemiDocument25 pagesAdugna LemiDr.Hira EmanNo ratings yet

- Work Experience:: Retail Logistics LLC Steinweg Sharaf Fze Sharaf Shipping Agency LLCDocument3 pagesWork Experience:: Retail Logistics LLC Steinweg Sharaf Fze Sharaf Shipping Agency LLCDr.Hira EmanNo ratings yet

- TB 1Document20 pagesTB 1Dr.Hira EmanNo ratings yet

- Toyota Vehicles For FemaleDocument4 pagesToyota Vehicles For FemaleDr.Hira EmanNo ratings yet

- Economic Research1Document11 pagesEconomic Research1Dr.Hira EmanNo ratings yet

- Internal Strengths Internal Weaknesses: StrategiesDocument1 pageInternal Strengths Internal Weaknesses: StrategiesDr.Hira Eman100% (1)

- Topic 6 - Islamic HRMDocument24 pagesTopic 6 - Islamic HRMhoshikawarinNo ratings yet

- Ielts Speaking Sample Week 8Document8 pagesIelts Speaking Sample Week 8Onyekachi JackNo ratings yet

- Spaghetti MetaDocument4 pagesSpaghetti MetasnoweverwyhereNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Case StudyDocument7 pagesHuman Resource Case StudyEka DarmadiNo ratings yet

- Converted KashmirDocument288 pagesConverted Kashmirapi-3719166No ratings yet

- Class 05 - Failure Analysis TechniquesDocument23 pagesClass 05 - Failure Analysis Techniquesb_shadid8399100% (1)

- Science Subject For Elementary 2nd Grade BiologyDocument55 pagesScience Subject For Elementary 2nd Grade BiologyClaudia Sari BerlianNo ratings yet

- Development of A Sunlight LuminaireDocument191 pagesDevelopment of A Sunlight LuminaireFREE BUSINESS INTELLIGENCENo ratings yet

- Rules For Hybrid StringingDocument3 pagesRules For Hybrid Stringingrhaudiogeek100% (1)

- Explanation TextDocument2 pagesExplanation Textmn bgsNo ratings yet

- Bowel Obstruction: Signs, Symptoms, and Emergency Management - Dr. Samrat JankarDocument2 pagesBowel Obstruction: Signs, Symptoms, and Emergency Management - Dr. Samrat JankarDr. Samrat JankarNo ratings yet

- Tree Town Teachers NotesDocument5 pagesTree Town Teachers NotesLinda WangNo ratings yet

- Bose The Untold Story of An Inconvenient NationalistDocument968 pagesBose The Untold Story of An Inconvenient NationalistSumit KhandaitNo ratings yet

- The Effects of TikTok Usage On Grade 11 Students of San Fabian National High SchoolDocument16 pagesThe Effects of TikTok Usage On Grade 11 Students of San Fabian National High SchoolKzz PerezNo ratings yet

- I. Eastern VS Western: Undself Reviewer: SemisDocument6 pagesI. Eastern VS Western: Undself Reviewer: Semislala gasNo ratings yet

- 7000 TroubleshootingMaintenanceDocument214 pages7000 TroubleshootingMaintenanceandreaNo ratings yet

- Scripts RhcsaDocument3 pagesScripts RhcsaDeshfoss Deepak100% (1)

- TABLE OF CONTENTS RpmsDocument3 pagesTABLE OF CONTENTS RpmsJaps De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Implementing A Risk Management FrameworkDocument51 pagesImplementing A Risk Management FrameworkSayyid ShalahuddinNo ratings yet

- Batik KawungDocument21 pagesBatik KawungYovan DickyNo ratings yet

- Standards Based Curriculum Development 課程發展實務: Karen Moreau, Assistant Superintendent for LearningDocument43 pagesStandards Based Curriculum Development 課程發展實務: Karen Moreau, Assistant Superintendent for Learningtrúc thuyên nguyễnNo ratings yet

- Application Letter.Document4 pagesApplication Letter.joanne riveraNo ratings yet

- Healing of The Spirit Chapters 1 32 PDFDocument267 pagesHealing of The Spirit Chapters 1 32 PDFpanamahunt22No ratings yet

- Action Plan in ARALING PANLIPUNANDocument2 pagesAction Plan in ARALING PANLIPUNANgina.guliman100% (1)