Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Generally Cambridge Group: Causing

Generally Cambridge Group: Causing

Uploaded by

girish19Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Generally Cambridge Group: Causing

Generally Cambridge Group: Causing

Uploaded by

girish19Copyright:

Available Formats

1396 MAY ,30, 1959

PROGNOSIS IN PROSTATIC CANCER

MEDIA URNAL

is often comparatively high. In such cases particular importance is attached to the need for thorough oestrogen therapy, since, if the growth can be brought under control by this means, the subsequent chances of survival appear to be improved. The choice of oestrogen merits careful consideration to ensure that a fully active preparation is employed, and from tracer experiments Fergusson' has so far been unable to confirm that the recently introduced phosphorylated compounds are superior in their effect except by virtue of the large dosages which can be given. Supplementary methods of endocrine control by adrenalectomy and pituitary inactivation, which are sometimes applied in relapsing cases, may also modify the later course of the disease. The likelihood of their success again appears to be related mainly to the early therapeutic response rather than to any specific pathological feature. This suggests that in prostatic cancer the outlook is determined to a greater extent by endocrine sensitivity than by histological grading or any other factor which can at present be measured in the laboratory. It is to be hoped that this new conception of growth activity will stimulate the introduction of some method of initial biological assay which will ultimately serve as a reliable guide to both the choice of treatment and the prognosis.

UMBILICAL SEPSIS AND ITS CONTROL

When the umbilical cord is cut and tied at delivery a raw area is left the best treatment for which is not yet settled. This stump of tissue separates from the infant by a process of gangrene which may be either wet or dry and, more important, may be sterile or infected. In maternity units attention has recently been focused on the umbilicus as a source of infection, and methods of dealing with the cord during the puerperium have been under review. A recent paper from the U.S.A. by J. P. Fairchild and colleagues1 reports not only that 80% of about a thousand infants had Staphylococcus aureus at this site but also that many infants carried haemolytic streptococci. Whether any of these were Lancefield Group A is not stated. This high rate of bacteriological, as distinct from clinical, infection may have been encouraged by the policy of allowing the cord to separate without the application of any form of antiseptic or dressing. When the "no dressing" technique is adopted, a

IFairchild, J. P., Graber, C. D., Vogel, E. H., jun., and Ingersoll, R. L., J. Pediat., 1958, 53, 538. 2 Boissard, J. M., and Eton, B., Brit. med. J., 1956, 2, 574. sKwant.s, W., and James, J. R. E., ibid., 1956, 2, 576. 4Colebrook, L., ibid., 1956, 2, 711. Jellard, J., ibid., 1957. 1, 925. Proc. roy. Soc. Med., 1957, 50, 705. 7 Colebrook, L., J. Obstet. Gynaec. Brit. Emp., 1936, 43, 691.

variety of organisms can be isolated from the umbilicus and tend to remain on the cord until it separates, though generally not causing a true inflammatory reaction. J. M. Boissard and B. Eton2 in Cambridge and W. Kwantes and J. R. E. James3 at Carmarthen have found the infant's umbilicus to harbour Group A haemolytic streptococci during outbreaks of puerperal sepsis, but it is interesting that in their cases as well as in those of Fairchild and colleagues the babies remained well. In fact, while there are many reports of trivial infections in these babies, it is rare for serious illness to result from infection of the umbilicus. Possibly maternity units sometimes do not hear of babies who are discharged well but later develop serious infection by way of the umbilical stump, for they may be admitted to other hospitals. Even so, the low incidence of infection in the presence of a high rate of carriage of organisms is striking, and there must be other factors such as trauma or debility which determine the occasional case of true umbilical sepsis. There are two separate problems-to prevent the occasional case of true umbilical sepsis, and to prevent the spread of organisms within the hospital by their carriage on the umbilical stump. It follows that the treatment of the cord after birth has two functions-to protect the baby from infection entering by way of the umbilicus, and to help break the cycle of carriers of hospital strains of organisms, in particular Staph. aureus and sometimes Group A haemolytic streptococci. Several years ago the routine was to apply a binder and pad, with or without a drying powder, which might contain an antiseptic. The disadvantages of this method were thought to be the irritation of the baby's skin, the harbouring of organisms by the usually wet binder, the extra work for nursing staff, and the additional handling of the baby. Opinion consequently swung against the use of any antiseptic or dressing on the cord, but it is since the latter technique has been adopted that persistent carriage of pathogenic organisms at this site has been observed. Owing to reports of this carrier state and consequent fears of true umbilical sepsis, the trend is now towards applying antibacterial agents to prevent the colonization by organisms of this open surface. There is no general agreement yet on which substances should be used for the purpose. Because of the danger of encouraging penicillin-resistant organisms, few people would now agree with Colebrook's4 suggestion for applying a penicillin cream, effective though this would be against haemolytic streptococci. Is fact, the problem of

MAY 30, 1959

UMBILICAL SEPSIS AND ITS CONTROL

,B

mo

1397

antibiotic-resistant strains of staphylococci is such that no systemically used antibiotic can be considered suitable. Ideally, an agent is required which will be an efficient antiseptic, be non-irritant to the babies' skin, will dry the cord, and assist separation; further, it should not stain the linen or have an unpleasant colour or smell. In addition, its use must not stimulate resistance to agents likely to be used in systemic treatment. The combination of crystal violet and brilliant green known as Bonney's Blue is most effective as an antiseptic, but cords so treated may tend to stay on longer than usual and the colour is not very acceptable to most mothers. J. Jellard5 has described good results with " triple dye," but this suffers from the same disadvantages. Chlorhexidine used as a 1% solution in spirit is most effective, does not irritate the skin, and, being nearly colourless, is pleasant to use. The stump so treated can then be protected with a strip of sterile gauze. As was shown at Queen Charlotte's Maternity Hospital,6 while various organisms can be isolated from the umbilicus on different occasions when such a routine is instituted, they do not maintain themselves there. There seems to be much to be said, then, for applying antiseptic to the cord and not leaving it unprotected ; but equally it is a mistake to regard the umbilicus as the primary source of infection in babies. Babies become infected with staphylococci from all their surroundings, and control of this organism can be achieved only by measures directed at all persons and things coming into contact with the infant. While the umbilicus may act as a transient carrier of streptococci, it cannot be regarded as the primary source of infection. Outbreaks of streptococcal sepsis will be prevented only by continued adherence to the careful technique for control of this infection originally described by Colebrook.7 The care of the umbilicus must remain only one of these.

VISCERAL REPLACEMENT The replacement of a diseased organ by an efficient substitute has been the subject of experimentformany years. Inert materials such as metal orsyntheticplastic

have been used with varying degrees of success in orthopaedic surgery; more recently, fabric grafts of woven plastic material have been inserted to bridge large arterial defects. In the latter case the graft is invaded by fibroblasts and the foreign material is incorporated into the new living vascular wall. The visceral cavities are lined with cells capable of withstanding fluids of unphysiological composition and of preventing the entry of micro-organisms into

the body; hence it is necessary that any prosthesis for replacing part of the gut should have an epithelial lining. Tubes lined by split-skin grafts are seldom satisfactory, and in practice the only suitable graft is a segment from another part of the alimentary tract. An isolated loop implanted into a new site may act merely as a conduit, but more usually it is needed in addition as a reservoir. Since an isolated segment of a viscus is not viable as a free graft, its blood supply must remain intact wherever it may be transplanted. It must therefore either be situated close to the defective organ which it is to replace or have a long, mobile vascular pedicle. Anastomosis of mesenteric blood vessels to those of somatic tissues near at hand-for instance, jejunal to internal mammary-has occasionally been successful, but the method is not generally suitable because of the high frequency of thrombosis. A reliable method of joining small vessels would be of great value in this field of surgery. Interest has been focused mainly on the replacement or modification of three visceraoesophagus, stomach, and bladder. The idea is not a recent one, for von Mikulicz is said' to have enlarged a contracted bladder with an isolated loop of ileum in 1898 and G. Kelling' used the ascending colon for oesophagoplasty in 1911. It is only in the last few years, however, that advances in surgical technique, chemotherapy, anaesthesia, and transfusion have made such procedures reasonably safe. The problem of providing a new reservoir for urine after cystectomy may be solved in several ways. The standard method of ureteric transplantation into the intact colon is followed too often by recurrent pyelonephritis. This complication may be avoided if the ureters are anastomosed to a loop of bowel which has been isolated and is no longer a faecal conduit. For instance, the colon may be divided at the rectosigmoid junction, the lower part closed, and the rectal ampulla used as a new bladder.3 Urinary continence is maintained by the rectal sphincters; an inguinal colostomy may be created for evacuation of faeces or alternatively the proximal end of the recto-sigmoid may be drawn down anterior to the rectum, passing through the anal sphincters, so that control of urine and faeces is established by the same group of muscles.4 Another method is to transplant the ureters into an isolated loop of ileum; one end may be brought to the skin to allow discharge of urine6

1 Tasker, J. H., Brit. J. Urol., 1953, 25, 349. 2 Kelling, 0., Zbl. ChIr., 1911, 38, 1209. 3 Pyrah, L. N., J. Urol. (Baltimore), 1957, 78, 683. 4 Lowsley, 0. S., and Johnson, T. H., ibid., 1955, 73, 83. Bricker, E. M., Surg. Clin. N. Amer., 1950, 30, 1511. Couvelaire, R., J. Urol. med. chlr., 1951, 57, 408. Scanlon, E. F., and Staloy, C. J., Sur. Gynec. Obstet., 1958, 107, 99. Henloy, F. A., Ann. toy. Coil. Surg. Engl., 1953, 13, 141. * Moronny, J., L4ancet, 1951, 1, 993.

You might also like

- Dental Practice ManagementDocument4 pagesDental Practice ManagementMahmoud MansourNo ratings yet

- Fluids For Transformer Cooling PDFDocument7 pagesFluids For Transformer Cooling PDFgirish19No ratings yet

- Target Audience Analysis Final DraftDocument4 pagesTarget Audience Analysis Final Draftapi-545798630No ratings yet

- Pleural EffusionDocument49 pagesPleural EffusionLyra Lorca86% (7)

- Omphalitis - Background, Pathophysiology, EpidemiologyDocument2 pagesOmphalitis - Background, Pathophysiology, EpidemiologykartikaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Otitis MediaDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Otitis Mediaamjatzukg100% (1)

- Plunging Ranula - Case Report EZADocument9 pagesPlunging Ranula - Case Report EZAreza kurniawanNo ratings yet

- Anomalies of The Penies ...Document6 pagesAnomalies of The Penies ...Firas Abu-SamraNo ratings yet

- Tetanus Neonatorum A Review of ManagementDocument5 pagesTetanus Neonatorum A Review of ManagementFrisiliakombaitan BaubauNo ratings yet

- Tetanus Neonatorum A Review of Management PDFDocument5 pagesTetanus Neonatorum A Review of Management PDFFrisiliakombaitan BaubauNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery CASE REPORTSDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery CASE REPORTSwidyaNo ratings yet

- 2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFDocument4 pages2.11 SEPTIC ABORTION AND SEPTIC SHOCK. M. Botes PDFteteh_thikeuNo ratings yet

- Cystic Fibrosis Research Paper ThesisDocument7 pagesCystic Fibrosis Research Paper Thesisfc34qtwg100% (2)

- Influence of The Intestinal Microbiome On Anastomotic Healing in The Colon and RectumDocument25 pagesInfluence of The Intestinal Microbiome On Anastomotic Healing in The Colon and RectumDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Management of The Child With Haematological Malignancy - BJA Education - Oxford AcademicDocument19 pagesAnaesthetic Management of The Child With Haematological Malignancy - BJA Education - Oxford Academicpradeep danielNo ratings yet

- Enterocolitis NecrosanteDocument21 pagesEnterocolitis NecrosantedenisNo ratings yet

- AmebiasisDocument10 pagesAmebiasisMuhammad RifkiNo ratings yet

- 781 2987 1 PBDocument3 pages781 2987 1 PBniroshniroshNo ratings yet

- Severe PsoriasisDocument4 pagesSevere PsoriasisAdelin Luthfiana FajrinNo ratings yet

- Neonatorum Due: Ophthalmia To Beta - Lactamase - ProducingDocument1 pageNeonatorum Due: Ophthalmia To Beta - Lactamase - ProducingReza Badruun Syahrul HakimNo ratings yet

- Saboo 2017Document6 pagesSaboo 2017jjeongjjangNo ratings yet

- Vesicovaginal FistulaDocument6 pagesVesicovaginal FistulaMaiza TusiminNo ratings yet

- Intussusception - A Case ReportDocument3 pagesIntussusception - A Case ReportAgustinus HuangNo ratings yet

- Intensive Care of The Neonatal FoalDocument32 pagesIntensive Care of The Neonatal FoalAristoteles Esteban Cine VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Errores Defecto de ParedDocument7 pagesErrores Defecto de ParedAlan La TorreNo ratings yet

- Indian AediatricDocument2 pagesIndian AediatricMuhamad RizauddinNo ratings yet

- Echinococcosis of The Spleen During Pregnancy: The Israel Medical Association Journal: IMAJ May 2001Document3 pagesEchinococcosis of The Spleen During Pregnancy: The Israel Medical Association Journal: IMAJ May 2001Ibtissam BelehssenNo ratings yet

- Review: Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 96: 263-271, 2007Document9 pagesReview: Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 96: 263-271, 2007Giorgio André Gabino GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Kontraindikasi CircumsisiDocument23 pagesKontraindikasi CircumsisiElfi MuazzamNo ratings yet

- IntususceptionDocument18 pagesIntususceptionColeen Angelique MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Management Acute General Peritonitis: THE OFDocument6 pagesManagement Acute General Peritonitis: THE OFNadia Puspita DewiNo ratings yet

- Tropical Immersion Foot2Document1 pageTropical Immersion Foot2Fenni OktoberryNo ratings yet

- Fetal Membrane Healing After Spontaneous and Iatrogenic Membrane Rupture: A Review of Current EvidenceDocument9 pagesFetal Membrane Healing After Spontaneous and Iatrogenic Membrane Rupture: A Review of Current EvidenceNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Older UrDocument10 pagesOlder UrCosmin CalanciaNo ratings yet

- HJKKDocument121 pagesHJKKSav GaNo ratings yet

- RVU en Niños 2015 LancetDocument9 pagesRVU en Niños 2015 LancetAnna De AguasNo ratings yet

- Umbilical Granuloma: Modern Understanding of Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and ManagementDocument6 pagesUmbilical Granuloma: Modern Understanding of Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and ManagementSari DewiNo ratings yet

- AppendicitisDocument4 pagesAppendicitisFebriyana SalehNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Empyema: A Case Report and Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesPaediatric Empyema: A Case Report and Literature ReviewphobicmdNo ratings yet

- Journal AbssDocument5 pagesJournal AbssMilanisti22No ratings yet

- OmphalitisDocument21 pagesOmphalitisdaisukeNo ratings yet

- Of A Fecal Management System: An in Vitro Investigation: Clostridium Difficile Containment PropertiesDocument9 pagesOf A Fecal Management System: An in Vitro Investigation: Clostridium Difficile Containment Propertiesana gomesNo ratings yet

- Amebiasis: Review ArticleDocument9 pagesAmebiasis: Review ArticleJouffrey Itaar MadridistaNo ratings yet

- Prenatal Toxoplasma Gondii: EditorialcommentaryDocument3 pagesPrenatal Toxoplasma Gondii: Editorialcommentarydiaa skamNo ratings yet

- Chemical Pleurodesis With Oxytetracycline in Congenital ChylothoraxDocument2 pagesChemical Pleurodesis With Oxytetracycline in Congenital ChylothoraxTommy YauNo ratings yet

- Infectious Endophthalmitis After: CataractDocument6 pagesInfectious Endophthalmitis After: CataractSurendar KesavanNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis CampylobacterDocument8 pagesMaster Thesis Campylobacterkathrynharrisvirginiabeach100% (2)

- Determination of The Transport Rate of Xenobiotics and Nanomaterials Across The Placenta Using The Ex Vivo Human Placental Perfusion ModelDocument7 pagesDetermination of The Transport Rate of Xenobiotics and Nanomaterials Across The Placenta Using The Ex Vivo Human Placental Perfusion ModelJosé Miguel DávilaNo ratings yet

- Hilton 2Document11 pagesHilton 2Rahadiyan HadinataNo ratings yet

- Endometritis PBIE Canisso2016Document16 pagesEndometritis PBIE Canisso2016kaathydanieelaNo ratings yet

- Pyloric Atresia - Edit FandyDocument9 pagesPyloric Atresia - Edit Fandyreza kurniawanNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Over Cystic FibrosisDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Over Cystic Fibrosisfvf8zrn0100% (1)

- Fimmu 04 00507 PDFDocument20 pagesFimmu 04 00507 PDFSilma FarrahaNo ratings yet

- Salmonella Typhi ThesisDocument8 pagesSalmonella Typhi Thesisalisonhallsaltlakecity100% (2)

- Acne and Bacteria Research PaperDocument7 pagesAcne and Bacteria Research Paperqwmojqund100% (1)

- 2019 - Appendicular Perforation in A NeonateDocument3 pages2019 - Appendicular Perforation in A NeonateRevivo RindaNo ratings yet

- Parasite BiologyDocument9 pagesParasite BiologyChris Tine BeduralNo ratings yet

- El Gohary2017Document17 pagesEl Gohary2017habiaunavezenchinaNo ratings yet

- Invaginasi 16903495Document4 pagesInvaginasi 16903495Fadhillawatie MaanaiyaNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Phimosis in ChildrenDocument7 pagesReview Article: Phimosis in ChildrenmerlinNo ratings yet

- Isrn Urology2012-707329 PDFDocument6 pagesIsrn Urology2012-707329 PDFNaomiRimaClaudyaNo ratings yet

- Gastroenterology For General SurgeonsFrom EverandGastroenterology For General SurgeonsMatthias W. WichmannNo ratings yet

- Guide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeFrom EverandGuide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeNo ratings yet

- 1077-2618/03/$17.00©2003 IeeeDocument6 pages1077-2618/03/$17.00©2003 Ieeegirish19No ratings yet

- GPS2BDocument40 pagesGPS2Bgirish19No ratings yet

- Collection A/c No. 31519633821 Collection A/c No. 31519633821Document1 pageCollection A/c No. 31519633821 Collection A/c No. 31519633821girish19No ratings yet

- Instruction Manual NewDocument253 pagesInstruction Manual NewManoj Garg100% (1)

- Phast7.0 ReleaseLetter&NoteDocument46 pagesPhast7.0 ReleaseLetter&Notegirish19No ratings yet

- Thermal Imaging Camera - Ti32Document42 pagesThermal Imaging Camera - Ti32rajpre1213No ratings yet

- Hac ModelDocument16 pagesHac Modelgirish19No ratings yet

- On Site Ignition Probabilities - HSE UKDocument192 pagesOn Site Ignition Probabilities - HSE UKgirish19No ratings yet

- Lecture NotesDocument255 pagesLecture NotessonuNo ratings yet

- Sulphur MsdsDocument28 pagesSulphur Msdsgirish19No ratings yet

- Industrial Plug Socket NewDocument12 pagesIndustrial Plug Socket Newgirish19No ratings yet

- Macros Word ExcelDocument43 pagesMacros Word Excelsunny171083_90123592No ratings yet

- Is 7931Document25 pagesIs 7931girish19No ratings yet

- Procedure For Determining Short Circuit Valuecss in Secondary Electrical Distribution Efsystes PDFDocument24 pagesProcedure For Determining Short Circuit Valuecss in Secondary Electrical Distribution Efsystes PDFgirish19No ratings yet

- 2 02 007 01 PDFDocument4 pages2 02 007 01 PDFgirish19No ratings yet

- Transformer Options For Fire Sensitive Locations: Type Advantages DisadvantagesDocument0 pagesTransformer Options For Fire Sensitive Locations: Type Advantages Disadvantagesgirish19No ratings yet

- Reference 2Document7 pagesReference 2Anonymous QPXAgjBwNo ratings yet

- Sexual Dysfunction in Depression and Anxiety - Conceptualizing Sexual Dysfunction As Part of An Internalizing DimensionDocument13 pagesSexual Dysfunction in Depression and Anxiety - Conceptualizing Sexual Dysfunction As Part of An Internalizing DimensionvickyreyeslucanoNo ratings yet

- Pallavi Dubey: Work ExperienceDocument3 pagesPallavi Dubey: Work ExperienceVasantNo ratings yet

- Triage BasicsDocument29 pagesTriage Basicsdrtaa62No ratings yet

- Study Guide For Nursing Research, 8th Edition - Geri LoBiondo-WoodDocument173 pagesStudy Guide For Nursing Research, 8th Edition - Geri LoBiondo-WoodAlexandru EsteraNo ratings yet

- HyperthyroidismDocument13 pagesHyperthyroidismEahrielle Andhrew PlataNo ratings yet

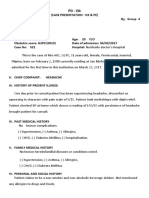

- Case Prese. PD GRP 4Document9 pagesCase Prese. PD GRP 4Bhargav GohelNo ratings yet

- 1514456610Syllabus-CMS and EDDocument5 pages1514456610Syllabus-CMS and EDUnderstanding HomoeopathyNo ratings yet

- Guillain Barre SyndromeDocument16 pagesGuillain Barre SyndromeNeha Rathore100% (1)

- Guidelines For Writing Goals and Desired Outcomes-Finals2Document4 pagesGuidelines For Writing Goals and Desired Outcomes-Finals2Kristine Aranna ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- DR Waseem Hammoudeh - Jordan and Hepatitis B Virus - Medics Index MemberDocument1 pageDR Waseem Hammoudeh - Jordan and Hepatitis B Virus - Medics Index MemberMedicsindex Telepin SlidecaseNo ratings yet

- Bredent Group Days Romania - 2nd SKY Fast & Fixed Forum - Speaker: Dr. Eugenia A. Michailidou DDS, MSc.Document1 pageBredent Group Days Romania - 2nd SKY Fast & Fixed Forum - Speaker: Dr. Eugenia A. Michailidou DDS, MSc.bredent_medical_roNo ratings yet

- CHN FinalsDocument6 pagesCHN FinalsSHERMINA HASAN100% (1)

- National Health Report 2003-Solomon IslandsDocument88 pagesNational Health Report 2003-Solomon IslandsMalefoasi100% (1)

- What Is A Stroke?: The Type of StrokeDocument14 pagesWhat Is A Stroke?: The Type of Strokediah fitriNo ratings yet

- Rectal Prolapse CaseDocument20 pagesRectal Prolapse CaseTonny ChenNo ratings yet

- Blood Type ADocument30 pagesBlood Type ANora EsmereldaNo ratings yet

- Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) Training of Ambulance Caregivers and Impact On Survival of Trauma VictimsDocument7 pagesPrehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) Training of Ambulance Caregivers and Impact On Survival of Trauma VictimsvenggyNo ratings yet

- Critical Evaluation GNMDocument7 pagesCritical Evaluation GNMManisha Samson100% (2)

- Biomarkers of Fruit and Vegetable Intake in HumanDocument22 pagesBiomarkers of Fruit and Vegetable Intake in HumanSie ningsihNo ratings yet

- ABG Interpretation - ATSDocument5 pagesABG Interpretation - ATSHAMMYER ALROKHAMINo ratings yet

- Kenya Relief Grant ProposalDocument31 pagesKenya Relief Grant ProposalgyrichardNo ratings yet

- Organic FoodDocument14 pagesOrganic FoodBangladeshiNo ratings yet

- Pre Intensive 1Document18 pagesPre Intensive 1liahekuriNo ratings yet

- Nursing TheoriesDocument13 pagesNursing TheoriesEmj Rocero PacisNo ratings yet

- NBME 7 - Answers & Explanations (SP)Document70 pagesNBME 7 - Answers & Explanations (SP)JUAN CHAVEZNo ratings yet

- 2019-297-Final Guidance - Principles of Premarket Pathways For Combination Products (1-25-22)Document25 pages2019-297-Final Guidance - Principles of Premarket Pathways For Combination Products (1-25-22)Rand OmNo ratings yet