Professional Documents

Culture Documents

URC - 2006 - Indigenous Self-Governance Practices of The Teduray

URC - 2006 - Indigenous Self-Governance Practices of The Teduray

Uploaded by

IP DevCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Discovery of Cells and The Development of Cell TheoryDocument2 pagesDiscovery of Cells and The Development of Cell TheoryCed HernandezNo ratings yet

- The C-Value Paradox, Junk DNA, and ENCODEDocument6 pagesThe C-Value Paradox, Junk DNA, and ENCODEMartina RajnovicNo ratings yet

- Intervening VariableDocument32 pagesIntervening VariableJhedine Sumbillo - TabaresNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper On DreamsDocument4 pagesConcept Paper On DreamsCeline Calma100% (2)

- 1 Original ManuscriptDocument70 pages1 Original ManuscriptLuis RamosNo ratings yet

- A Quick and Simple FISH Protocol With Hybridization-Sensitive Fluorescent Linear Oligodeoxynucleotide ProbesDocument10 pagesA Quick and Simple FISH Protocol With Hybridization-Sensitive Fluorescent Linear Oligodeoxynucleotide ProbesNidhi JaisNo ratings yet

- Human Genome ProjectDocument5 pagesHuman Genome ProjectKyle Ambis SyNo ratings yet

- Origins of Life: A D D S C DDocument23 pagesOrigins of Life: A D D S C DjonasgoNo ratings yet

- Aryan Roots in Chinese .: Ede - InsDocument6 pagesAryan Roots in Chinese .: Ede - InsMario GriffinNo ratings yet

- Evolution First NoteDocument9 pagesEvolution First NoteTULSI SHARMANo ratings yet

- Lest We Forget! by Nicole Sadighi-Family Security Matters PDFDocument3 pagesLest We Forget! by Nicole Sadighi-Family Security Matters PDFnicolekian100% (1)

- Beginnings: 1.1 (Sorta) How Math WorksDocument11 pagesBeginnings: 1.1 (Sorta) How Math WorksBace HickamNo ratings yet

- Eternal LawDocument34 pagesEternal LawMaam PreiNo ratings yet

- Modern Synthetic TheoryDocument22 pagesModern Synthetic TheoryKamran SadiqNo ratings yet

- Fossil Mystery: Read The Short Story. Then Answer Each QuestionDocument4 pagesFossil Mystery: Read The Short Story. Then Answer Each QuestionULTRA INSTINCTNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Freedom: David MolineauxDocument2 pagesCosmic Freedom: David Molineauxsalomon46No ratings yet

- GR No 135385 PDFDocument94 pagesGR No 135385 PDFRanger Rodz TennysonNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 - Sociological PerspectivesDocument33 pagesLesson 3 - Sociological PerspectivesArianna NicoleNo ratings yet

- Advanced Powder TechnologyDocument11 pagesAdvanced Powder TechnologyDeepakrao Bornare PatilNo ratings yet

- Good Shepherd Cathedral MinistriesDocument41 pagesGood Shepherd Cathedral MinistriesomgpopNo ratings yet

- Ant 101: Introduction To Anthropology: Lecture 16: Human EvolutionDocument27 pagesAnt 101: Introduction To Anthropology: Lecture 16: Human EvolutionAmina MatinNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Revolutions That Defined Society: Reporters: Nathalie de Leon Dianne de Guzman BSBA 1-7Document15 pagesIntellectual Revolutions That Defined Society: Reporters: Nathalie de Leon Dianne de Guzman BSBA 1-7Fitz Clark LobarbioNo ratings yet

- 5 Ancient Theories On Origin of LifeDocument8 pages5 Ancient Theories On Origin of LifeNorberto R. BautistaNo ratings yet

- Molluscs in Mangroves PDFDocument12 pagesMolluscs in Mangroves PDFEnrique MartinezNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology and SocietyDocument40 pagesScience, Technology and Societygabbycervantes30No ratings yet

- Copernican TheoryDocument2 pagesCopernican TheoryAbigael JacobNo ratings yet

- Loss of Reading Habit Among The YouthDocument19 pagesLoss of Reading Habit Among The YouthDeepanjan Biswas100% (2)

- 1.the Science of EcologyDocument15 pages1.the Science of EcologyMerlito Fancubila Flagne Jr.No ratings yet

- Philo 1N BookDocument139 pagesPhilo 1N BookLuke BeanieNo ratings yet

- Magic and Medicine The Power of Seals IDocument6 pagesMagic and Medicine The Power of Seals Itroy thomsonNo ratings yet

- Crosswise Copy and AnswerDocument32 pagesCrosswise Copy and Answerflorie jane macayaNo ratings yet

- Human EvolutionDocument9 pagesHuman EvolutionVinod BhaskarNo ratings yet

- IucnDocument34 pagesIucnsaaisNo ratings yet

- Blue Miracle Super Liquid PDFDocument11 pagesBlue Miracle Super Liquid PDFJoseph Cloyd L. LamberteNo ratings yet

- Homo HabilisDocument3 pagesHomo HabilisGlutton ArchNo ratings yet

- Genomic Equivalence: DefinitionDocument5 pagesGenomic Equivalence: Definitionjgfjhf arwtrNo ratings yet

- Ecology A Branch of Biology (From Greek: "House" and "Study Of") Is TheDocument4 pagesEcology A Branch of Biology (From Greek: "House" and "Study Of") Is TheImmanuel HostNo ratings yet

- A Study On Relationship Between Academic Stress and Coping Strategies Among Adolescent BoardersDocument15 pagesA Study On Relationship Between Academic Stress and Coping Strategies Among Adolescent Boardersstefi5No ratings yet

- Genetic EngineeringDocument6 pagesGenetic Engineeringsarguss14100% (1)

- Nonvisual Photoreceptors of The PinealDocument36 pagesNonvisual Photoreceptors of The Pinealrambo_style19No ratings yet

- Summary of Laudato Si - NATRESDocument3 pagesSummary of Laudato Si - NATRESZarah Jeanine100% (1)

- A Newly Discovered Manuscript of The Hi PDFDocument29 pagesA Newly Discovered Manuscript of The Hi PDFCarlos VNo ratings yet

- Divine Law Theory & Natural Law TheoryDocument20 pagesDivine Law Theory & Natural Law TheoryMaica LectanaNo ratings yet

- Revealing The Hidden: The Epiphanic Dimension of Games and SportDocument31 pagesRevealing The Hidden: The Epiphanic Dimension of Games and SportXimena BantarNo ratings yet

- The Self From Various Philosophical Perspectives: Who Are You?Document7 pagesThe Self From Various Philosophical Perspectives: Who Are You?Donnalee NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Interrelationship of Political Science With Other Branches of LearningDocument2 pagesInterrelationship of Political Science With Other Branches of LearningJeffrey Calicdan Bucala100% (1)

- Tree of Life and SystematicsDocument10 pagesTree of Life and SystematicsRhob BaquiranNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 3 Intellectual Revolution That Define SocietyDocument27 pagesCHAPTER 3 Intellectual Revolution That Define SocietyYna Mae Sto DomingoNo ratings yet

- White Paper XIDocument21 pagesWhite Paper XIhola123456789jgNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Training FDocument9 pagesTransfer of Training FKerwin Misael HipolitoNo ratings yet

- Aristotle Four CausesDocument1 pageAristotle Four CausesMasoud NassorNo ratings yet

- STS Module 3A The Scientific Revolution (ACQUIRE)Document3 pagesSTS Module 3A The Scientific Revolution (ACQUIRE)GraceNo ratings yet

- Last Na TalagaDocument74 pagesLast Na TalagaJemica RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Trindade 2008: Reconciling Conflicting Paradigms: An East Timorese Vision of The Ideal StateDocument27 pagesTrindade 2008: Reconciling Conflicting Paradigms: An East Timorese Vision of The Ideal StateJosh TrindadeNo ratings yet

- LARMOUR - Culture and Democraty in The Pacific IslandsDocument13 pagesLARMOUR - Culture and Democraty in The Pacific IslandssutbangNo ratings yet

- Position PaperDocument5 pagesPosition PaperOOFOUCHIENo ratings yet

- Taylor E B 2009 Modern Dominicanidad Nat PDFDocument9 pagesTaylor E B 2009 Modern Dominicanidad Nat PDFJhoan Almonte MateoNo ratings yet

- Hirtz, Indigeneity, 2003Document29 pagesHirtz, Indigeneity, 2003cristinaioana56No ratings yet

- The Concept of Justice Among The Talaandig of LantapanDocument15 pagesThe Concept of Justice Among The Talaandig of LantapanTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Mou Forges Armm-Ipdev Cooperation: What'S Inside?Document12 pagesMou Forges Armm-Ipdev Cooperation: What'S Inside?IP DevNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 2-3Document15 pagesKetindeg 2-3IP DevNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 4Document11 pagesKetindeg 4IP Dev100% (1)

- Ketindeg 10 (Final Issue)Document56 pagesKetindeg 10 (Final Issue)IP DevNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Ritual For PeaceDocument2 pagesIndigenous Ritual For PeaceIP DevNo ratings yet

- DepEd Guidelines On The Conduct of Activities and Use of Materials Involving Aspects of Indigenous CultureDocument11 pagesDepEd Guidelines On The Conduct of Activities and Use of Materials Involving Aspects of Indigenous CultureIP DevNo ratings yet

- FADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFDocument9 pagesFADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFIP DevNo ratings yet

- Program Flow RTD On The Promotion and Protection of IP Child and Maternal Health CareDocument1 pageProgram Flow RTD On The Promotion and Protection of IP Child and Maternal Health CareIP DevNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceDocument2 pagesThe Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceIP DevNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 9 - Vol 3 Issue 1Document17 pagesKetindeg 9 - Vol 3 Issue 1IP DevNo ratings yet

- 1st IP Cultural Festival Proposed Program FlowDocument1 page1st IP Cultural Festival Proposed Program FlowIP DevNo ratings yet

- Program Flow (Detailed)Document2 pagesProgram Flow (Detailed)IP DevNo ratings yet

- Invitation To EveryoneDocument1 pageInvitation To EveryoneIP Dev100% (1)

- Draft Implementing Rules & Regulations of RA 10368Document40 pagesDraft Implementing Rules & Regulations of RA 10368IP DevNo ratings yet

- Ubo Brief HistoryDocument15 pagesUbo Brief HistoryIP Dev100% (8)

- DepEd Order No.62, s.2011Document7 pagesDepEd Order No.62, s.2011IP Dev75% (4)

- IPDEV Data: Demographic Data of Lumads in Mainland ARMMDocument14 pagesIPDEV Data: Demographic Data of Lumads in Mainland ARMMIP DevNo ratings yet

- 154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao City 154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao CityDocument1 page154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao City 154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao CityIP DevNo ratings yet

- Đề 1. Ô tô trên cầuDocument29 pagesĐề 1. Ô tô trên cầuNguyen HoangNo ratings yet

- System". This Project Is A Web Based Application Developed in PHP and Mysql5 Xamp AsDocument23 pagesSystem". This Project Is A Web Based Application Developed in PHP and Mysql5 Xamp AsKeerthi Vasan LNo ratings yet

- Studying: Live Lesson NotesDocument12 pagesStudying: Live Lesson NotesHà MyNo ratings yet

- Cleveland 1-13 1Document2 pagesCleveland 1-13 1api-540028125No ratings yet

- Diploma in Mechanical Engineering by M SCHEMEDocument217 pagesDiploma in Mechanical Engineering by M SCHEMEMovies SpecialNo ratings yet

- The Young Crab and His Mother 3Document7 pagesThe Young Crab and His Mother 3Donnette DavisNo ratings yet

- Bader Abdul MajidDocument2 pagesBader Abdul Majidma saNo ratings yet

- Jay Adrian HGDocument5 pagesJay Adrian HGadrian lozano0% (1)

- Fia NyDocument1 pageFia NyThe Capitol PressroomNo ratings yet

- Phases in The Evolution of Public AdministrationDocument104 pagesPhases in The Evolution of Public Administrationaubrey rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Counseling ProcessDocument26 pagesCounseling ProcessAbang RamlanNo ratings yet

- Jenny JournalDocument27 pagesJenny JournalmaviinreyNo ratings yet

- English Exercise SheetDocument10 pagesEnglish Exercise SheetAndreea DemianNo ratings yet

- SHORT SD3-360 - SKYbrary Aviation SafetyDocument3 pagesSHORT SD3-360 - SKYbrary Aviation SafetyAnonymous d8N4gqNo ratings yet

- Home Invasion: Robbers Disclose What You Should KnowDocument19 pagesHome Invasion: Robbers Disclose What You Should KnowLittleWhiteBakkie100% (2)

- Pearson Test of English: Young LearnersDocument52 pagesPearson Test of English: Young LearnersGaolanNo ratings yet

- Indian Polity 10Document3 pagesIndian Polity 10Ramesh KurahattiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Factors in Choosing Location and Design of Port: Lecturer: Puan Umikalthum Binti ZulkeflyDocument8 pagesChapter 4: Factors in Choosing Location and Design of Port: Lecturer: Puan Umikalthum Binti ZulkeflyKausalya SankaranNo ratings yet

- Community HelpersDocument6 pagesCommunity HelpersLiz GardnerNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument20 pagesResearchjohn3ruiz3delfinNo ratings yet

- Christian Stokes Resume May20Document2 pagesChristian Stokes Resume May20api-510602244No ratings yet

- Courses: This Is Not An Official Academic RecordDocument2 pagesCourses: This Is Not An Official Academic RecordMartin GohNo ratings yet

- Nancy Beatriz Cahuana Saavedra Unidad 3Document3 pagesNancy Beatriz Cahuana Saavedra Unidad 3Jjeferson JavierNo ratings yet

- b-3087 Final Project ChoicesDocument3 pagesb-3087 Final Project Choicesapi-527115066No ratings yet

- Advanced Simulation of Rolling Element Bearings For Bearing Designers and Application EngineersDocument2 pagesAdvanced Simulation of Rolling Element Bearings For Bearing Designers and Application Engineersmohsin2014No ratings yet

- Eureka Math Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesEureka Math Lesson Planapi-479297618No ratings yet

- Super Six ParenthandoutDocument4 pagesSuper Six ParenthandoutNelson VersozaNo ratings yet

- Faizal Khan: Mobile +91 8291666788 - Email Id: Linkedin Profile: Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Willing To Relocate)Document2 pagesFaizal Khan: Mobile +91 8291666788 - Email Id: Linkedin Profile: Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Willing To Relocate)Faizal KhanNo ratings yet

- HR Docs & Templates - CompleteDocument8 pagesHR Docs & Templates - CompleteShahid Anwar50% (2)

- CNN Student News Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesCNN Student News Lesson PlanMegan CourtneyNo ratings yet

URC - 2006 - Indigenous Self-Governance Practices of The Teduray

URC - 2006 - Indigenous Self-Governance Practices of The Teduray

Uploaded by

IP DevOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

URC - 2006 - Indigenous Self-Governance Practices of The Teduray

URC - 2006 - Indigenous Self-Governance Practices of The Teduray

Uploaded by

IP DevCopyright:

Available Formats

Notre Dame-U:niversity

CotabatQ C:ity

Research Monograph No. 30

Indigenous Self-Governance Practices

of the Teduray

This Research Monograph Series presents t h t ~

researches conducted by the University Research Cen

Notre Dame University, Cotabato City

Socio-Economic Research Center October 2006

Research Monograph No. 30

Indigenous Self-Governance Practices

of the Teduray

This project was conducted by the University Research Center, A'otre Dame

University in partnership with the International Labor Organization

(ILO) and the Planning and Development Office, ARMM, June 2006

The TEDURAY of Upi, Maguindanao (by: Re,rDoniloLacson, RmarchAssociale, LRC)

Key Concepts in the Traditional Teduray Governance and

Leadership Structure

The Teduray is one of the 18 indigenous ethno-linguistic

groups originally inhabiting the island of Mindanao,

Philippines. Today, as it was since time immemorial, Teduray

communities are largely concentrated in the towns of South

Upi (Timanan) and North Upi (Upi), Maguindanao Province,

ARMM (6

0

53'N latitude; 124

0

02'E longitude).

In the beginning of the American occupation in the

1900s, provinces and towns were created as the new geo

political delineation out of the different indigenous villages

and settlements in Mindanao. Until that time, Teduray

communities were politically subjugated to the larger

Maguindanao Sultanate which the Muslims established as

early as 1450 ' (Rodil, 1994). Later, the Americans

transformed the sultanate into Special Moro Province and

much later, into Empire Cotabato Province. Specifically, the

Teduray territory of Upi was officially designated as a barrio

of Dalican (now Municipality of Datu Odin Sinsuat).The

influx of I1ocanos from Luzon and I1onggos from Visayas in

the 1920s increased the area's population and consequently

pmvered its economic (agricultural) grm:V1h.

"

In 1957, Upi weaned away from its geo-political

dependence on Dalican and eventually became another

municipality of the Empire Cotabato Province. On October

26, 1976 Upi, was divided into North Upi and South Upi

upon the issuance of Presidential Decree (PD) No. 1046.

North Upi retained the name Upi, while South Upi became

known as Timanan. Presently, Upi has a total Teduray

population of 12,164 and Timanan has 37,697 total Teduray

I

population (Notre Dame University Research Center, 2004).

These figures constitute roughly 8% of the 662,180 total

population of Maguindanao Province (ARMM Socio

economic profile, 2000).

The same ethnic groups of Ilocanos, Ilonggos

(Christians), Magindanaons (Muslims), and Tedurays

(Indigenous People) predominantly define the Tri-people

composition of Upi and Timanan populations. Timanan is

presently headed by a Teduray mayor who was eventually

sworn-in to the position after a much-heated and violent

electoral contest in 2002. On the other hand, a more peaceful

electoral contest finally installed a Teduray mayor in Upi

after a long succession of Magindanaon (Muslim) mayors

since 1957.

Just like the other indigenous groups in Mindanao, much

of the Teduray geo-political history is kept and transmitted

through oral form. A few written materials focus on Teduray

laws and conflict resolution processes such as those written

by Schlegel (1970). But the larger Teduray historical resource

remains undocumented. Very recently, in 2002, a tribal

initiative was undertaken to put into writing a brief history

and the salient political features of the Timuay Justice and

Governance (TGJ) system.

:I Teduray leaders and elders insist that before the coming

of Islam and Christianity in this part of the globe, there were

8 original Indigenous People (IP) tribes in South-Central

Mindanao that used to practice the Timuay System (sic)1 of

governance as mode of socio-political arrangement. Those

tribes were: Subanen, Teduray, Lambangian (Half Teduray),

J The ternl Timuay System is just a contemporary constructed terminology

referring to the traditional political structure pervading the 8 indigenous tribes of

central Mindanao befor.: Islam came to Mindanao.

2

Dulangan Manobo, T'Boli, Blaan, Bagobo, and Arumanen

Manuvu. In this particular system, the Timuay is the

recognized leader of the village, territory, and community.

Timuay comes from the generic Manobo term, "timu" (to

gather). Literally, Timuay refers to the person who, by all

account of social, economic, and political status, gathers the

people (Lacson, 2005). Today, these tribes still appropriate

the concept of Timuay as leader.

However, the Teduray believe that before the

introduction of the Sultanate governance system (Islam)

around 1450 and the colonial governance system (Christian)

around 1565, all indigenous societies in South-Central

Mindanao followed the Timuay governance system, which

was functioning effectively at the level of each individual

tribe (TJG 2003). This claim may have strong validity

considering that, even today, the aforementioned groups still

refer to the Timuay as main political figure (Alejo 2002;

Rodil, 1994; & Lacson, 2005). In fact, the Timuay system

was evolving towards the establishment of a consolidated

inter-tribal governance when the introduction of the sultanate

system first disrupted the process. Subsequent colonial and

imperial govemments respectively thwarted the maturing of

the Timuay System (TJG, 2003).

The Timuay occupies the highest position in the

traditional political hierarchy. He is always a male. In the

past, such position was not confined to mere politica}

functions. By mode of operation, the Timuay was the point of

socio-political reference. The community always perceived

him as an individual set apart for political leadership as

prescribed in the Adat (traditional Teduray set of standards of

conduct and obligations). There were two bases for becoming

Timuay: (a) by inheritance (being the eldest son of a Timuay)

and (b) being personally chosen by the Timuay. In a recent

survey of 30 households in Rifao, respondents unanimously

3

assert that the most outstanding quality of Timuay is, "May

kakayahang mamuno sa komunidad" (ability to lead the

people). Communal identity was linked with him whereby

people's geographic and political affiliations were oriented to

the Timuay territorial sway of influence or sakuf It is within

the same sphere of understanding that the Teduray used to

arrange their Fenuwo (villages) and Inged (territories) in the

most organic level.

In spite of the pre-eminence of his position, the Timuay

was not the sole figurehead in the Teduray society.

Traditionally, individuals and parties looked up to the

Kefedewan for representation during fonnal negotiations of

agreements such as marriage, and non-violent settlement of

disputes. He was generally considered the legal authority who

together with other Kefedewan comprised a respected group

of individuals with the following extraordinary skills: (a)

strong memory especially of details pertammg to

consummated agreements, (b) comprehensive knowledge of

the fine lines of the Kitab Kaedatan (customs), (c) mastery of

the "binuwaya" (euphemistic) style of speaking, (d)

persuasive but polite manner of articulation of ideas, and (e)

consistent display of patience and cool-headedness even

during the most heated negotiation process. These also serve

as criteria for becoming Kefedewan. In the present socio

political context, the Teduray still apply the same criteria in

their Kefedewan and still look up to him with the

same regard. The recent survey in Rifao presents a simpler

understanding of those qualities, as: magaling magsalita

(articulate speaker), walang kinakampihan (does not show

favoritism), marunong sa batas na katutubo (knowledgeable

in customary law), mapasensiya (patient), rnatibay ang

memOJya (superb memory).

The tenn Kefedewan is derived from the root wordfedew,

which means "feelings". Timuay Alim Bandara, the Timuay

Labi (Chief Executive) of the Timuay Justice and

Governance, explained, "Ang Kefedewan ay tinaguriang

doctor ng fedew. Siya ang taga-ayos at nagpapagaling ng

nasirang damdarnin ng mga tao" (The Kefedewan is the

doctor of feelings. He cures the hurt feelings of people). He

perfonns his noble service through a "tiyawan" (formal

adjudicatory discussion), where he represents individuals and

parties in the traditional conflict resolution process. By

operation, the Kefedewan is comparable to an attorney. His

position is not preordained. Just like the ordinary court

attorney, he gradually develops his skills and builds his name

within the Kefedewan trade. But unlike the court attorney,

the Kefedewan also pays "tamuk" (blood price or fine) for his

client in cases where the latter is demanded to pay for a crime

or transgression committed. A Kefedewan who is always

willing to do this is accorded with high regard in the

community. The reverse action makes a Kefedewan disdainful

and untrustworthy in the eyes of his villagemates (Schlegel,

1970). Most importantly, however, the Kefedewan always

aims to settle issues on a win-win solution together with other

Kefedewan involved in a Tiyawan. When on it, the

Kefedewan keeps at the core of his concerns the attainment of

justice which restores good "fedew" (feelings) in terms of

respect for rights and feelings of all people involved. Schlegel

elaborates:

Kefedewan represent a particular person - more

accurately, a paI1icular person and his kindred

but they do not contend in the manner of trial

lawyers in adversary proceedings. They do not

try to win for their side. Together, all

Kefedewan participating in a Tiyawan are

expected to strive eamestly to achieve a

situation where all "benal" has been recognized,

where those responsible for the trouble have

through their Kefedewan - accepted their

4 5

responsibility and fault and have been properly

fined, so that all fedew have been made good

(fiyo). Kefedewan act much more like a

fraternity of judges than like an array of

lawyers; they are committed as a group to an

ultimate respect for just decisions that set every

fedew right. Among Kefedewan this

commitment is an-important. (Schlegel, 1970,

p. 61)

A person who trusts his fedew to a particular Kefedewan

becomes a sakuf of the later. However, such relationship is

not political in nature. The Kefedewan is not bound to the

personal interest of his sakuf but to the task of setting all

things in good and harmonious state. Primarily, the

Kefedewan has no political power. Schlegel explains further:

Although the decisions of Kefedewan have

authority, they cannot be backed by force. Legal

leaders among the traditional Tiruray are

authoritative; they are not powerful. A decision

that someone was at fault and should be fined is

made and accepted by men who are completely

powerless to force acceptance of any decision.

They cannot have anyone beaten, ostracized,

imprisoned in any sense, or executed. (Ibid,

" 1970, p. 65)

The arena within which the Kefedewan actualizes his

unique function is the Tiyawan - meaning, "to converse" with

a singular aim of arriving at a common decision. The activity

within which this purposive conversation is undertaken is

called setiyawan - literally means 'to adjudicate together".

These considerations deliver the concept of Tiyawan as a

fonn of surface litigation.

It is to his Kefedewan that a person reports, when he/she

wants to forge some formal agreements with other persons.

Commonly, this takes the form of marriage arrangement or

conflict resolution process. Then the Kefedewan approaches

the Kefedewan of the other party (either personally or through

a messenger) to set a date for the Tiyawan. After which, the

parties concerned are notified about that very important

appointment. Within the Tiyawan itself, the overall rationale

is to adjudicate together.

Basically, the Kefedewan and Tiyawan are two major

components of a synergetic mechanism within the socio

cultural system whose primary function is to halmonize all

human transactions within the frame of the Kitab Kaedatan

(customary law specifically prioritizing respect).

The Bliyan (or Beliyan) is the clairvoyant medicine

person. He/she is not chosen by the people. He/she is

endowed with the knowledge and power to communicate with

unseen entities. As such, he/she serves as the primary

consultant in the Fenuwo. Aside from attending to the

maladies of hislher village mates, the Bliyan is consulted on

mundane matters such as: planting, hunting, harvesting,

fishing, and all ritual activities for thanksgiving, cleansing,

wedding, and burial.

In summary, the traditional Teduray self-governance had

the following key concepts/elements:

1. Governance - Timuay, Kefedewan, Bliyan

2. People - Sakuf (village-based)

3. Territory - Fenuwo (village), Inged (territory)

4. Sovereignty-Did not mature into federal collectivity

(remained village-bound)

5. Representation - Kefedewan and Tiyawan (village

based)

6

7

Political Ascendancy

Ordinary Teduray folks today know that election is the

process of choosing leaders in the present mainstream

governance system. However, they also know that there was a

different process in the past. Accordingly, traditional political

ascendancy used to be based on two modes: (a) by inheritance

and (b) being chosen by the Timuay. The Timuay, Kefedewan,

and Bliyen were not voted upon by the people. Holders of

those positions got these by inheritance, by being selected by

a leader or a group of leaders, and, in the case of the Bliyan,

as supernatural gift. Vivid memory and strong belief in the

traditional process prompted one Teduray Local Government

Official (LGO) to declare confidently that "Ang eleksiyon ay

hindi naaangkop sa sistema ng Teduray" (Election [voting] is

not compatible with the Teduray system). Another Timuay

said, "Noong unang panahon, walang kasulatan. Pag

uusapan lang ng mga Timuay ang pagpili ng lider dahil hindi

nakapag-aral ang mga tao. Walang batas na sinusunod na

kagaya sa eleksiyon natin ngayon. Wala rin kasulatan. Ang

sinusunod na batayan ay ayon sa galing" (In the past, there

were no written documents. The process of choosing a leader

was done through Timuay discussions because people were

illiterate. There was no legal basis to follow. Basic criteria

were simply based on skills and expertise). They added that,

"Kapag Timuay 0 Kefedewan ka, hanggang mamatay ka, di

k a ~ papaliran" (When you are a recognized Timuay or

Kefedewan; you are never replaced until you die).

Accordingly, the selection was based on traditional qualities

ascribed to leaders, such as: may kakayahang mamuno sa

komunidad (ability to lead the community), magaling

nwgsalita (articulate speaker), walang kinakampihan (does

not show favoritism), marunong sa batas na katutubo

(knowledgeable in customary law), may pasensiya (patient),

and matibay ang memolya (superb memory). These qualities

were major considerations for someone to become leader. Or,

8

if someone was destined to become a leader by virtue of

inheritance, he had to develop these same qualities in order to

gradually fit into his preordained position. FGD participants

assert that the, " .. .Kefedewan ay dapat talaga mahusay

magsalita at magaling sa batas ng tribo" (the Kefedewan,

first and foremost, must be articulate and expert in customary

laws).

Leaders' Functions, Duties, and Responsibilities

Respondents in this study unanimously agree that the

main task of traditional leaders in the past was to settle

disputes in the village and to implement the Kitab Kaedatan

(tribal laws). Accordingly, the traditional leaders' task was,

" .. . taga-ayos ng mga problema sa komunidacf' (settles

problems in the community). Specifically, the Timuay was

looked up as figurehead of the territory to whom people' s

political affiliation was anchored. Nevertheless, his

relationship to his sakuf was not servile nor feudal in

character. Except for making sure that their territory was at

peace with neighboring territories by maintaining friendly

alliances, a Timuay was perceived as just another village

farmer among his village-mates. Such relationship was in

harmony with the Teduray egalitarian social character.

The Kefedewan and the Tiyawan are the conflict

resolution mechanisms of the community. These exist and

function symbiotically to maintain interpersonal harmony and

peace, as well as a form of social control to align individual

and communal behavior with the Kitab Kaedatan (customary

laws). Sanctions for misbehavior are finalized in the Tiymvan.

The whole community enforces the punishment with

ostracism as an ultimate punishment.

Today, Teduray communities still prefer local officials to

resolve conflict in the traditional manner especially when the

9

----------------------------------------------

disputants are all Teduray. In such cases, even Barangay

officials recommend that disputes be settled in the manner

following tribal customs. One major reason for this

preference lies in the traditional principle governing conflict

resolution wherein parties in disputes are always led to a win

win settlement with the restoration of peaceful relation as an

end product.

:,

Current Challenges and Opportunities in Teduray Governance

t

When the Municipality ofUpi was first established, it had

a Teduray as its first Mayor. After him, Moro (Muslim)

mayors, all from the Sinsuat Clan, succeeded to the position

one after the other. It was only in the last local elections that a

Teduray mayor was elected. Accordingly, the Sinsuats who

sat as Mayors were at the same time Datus in the traditional

Moro social setup. By operation, they were traditional Moro

Datus who have become mayors in the mainstream

governance setup. A Key Informant relates: "Ang mga naging

Mayor na Sinsuat ay mga kilalang Datu ng mga Muslim

(Moro). Noon pa man, bago pa ang mainstream na sistema,

may dati nang pakikipag-ugnayan ang mga Datu ng Muslim

at mga Timuay ng Teduray. Ang ganitong ugnayan ay siyang

dinala ng mga Sinsuat noong sila ang mga naging mayor ng

Upi. So, ang pagiging Mayor nila sa mainstream na sistema

ay sa titulo lang. Ngunit sa katotohanan, ang sistemang Datu

at Timuay pa rin ang pinalakad nita. OK rin sa amin yun kasi

doon kami sanay at alam namin kung papaano kami

magkonekta sa pamunuan. Actually, kahit sa ngayon, sa

l

pamayanan ng mga Muslim kagaya ng Shariff Aguak ay Datu

{

system talaga ang patakbo. Kaya nga totoo yung sabi nila na

sa buong bayan ng Shariff Aguak ay walang eleksiyon.

Seleksiyon lang, kasi ganun talaga sa dating sistema ng Datu

at Timuay. Dumaan sila sa proseso ng kung saan tinatalaga

sila bitang fider at hindi pinagpipilian ng mga tao. Yun ang

'1

sistemang mahabang panahon naming naisabuhay at

10

talagang naintindihan ng kahit mga ordinaryong" mga tao

namin.

Kaya ngayon, kahit na naihalal na bilang Mayor 0

Barangay Chairman ang iba sa amin, ang pagtingin ng mga

tao namin sa kanila ay kagaya noong dating pagtingin na

para sa mga Timuay. Sa ngayon, Teduray na ang mayor. Ang

isa sa kahirapan niya ngayon ay di niya ma-duplicate ang

ganuong relasyon dahil hindi naman siya Datu. Sa isipan ng

mga tao, ganun pa rin ang pakikitungo. Hindi niya kasalanan

kung hindi niya matugunan ito. Sincere lang siya na

gampanan ang dapat niya gampanan sa mainstream system.

Mahirap lang kasi, hindi pa malawak ang pagka-intindi ng

mga tao sa mainstream system. Sa ngayon, hirap na hirap

siya kung papaano madiskartehan ang problemang ito. Isa

pa, sa Teduray kasi, pantay kami lahat. Walang ideya ng

constituency. Ang mga fider ay tagapagtaguyod lang ng

kapakanan ng mga tao. Pero maliban doon, wala sa amin

ang nangingibabaw ang posisyon sa. buhay. Ito ang naging

principal value sa pagtatag ng T JG - pantay-pantay lahat

kasama ang mga lider" (Members of the Sinsuat clan who

became mayors were known Datu of the Moros (Muslims).

Even before the establishment of the mainstream system,

there was already link between the Muslim Datus and

Teduray Timuays. The same linkage was sustained by the

Sinsuats when they sat as mayors of Upi. So, their being

mayors in the mainstream system was simply titular in nature.

In truth, it was the Datu- Timuay linkage they were

implementing. It was OK for us then, because it was the way

we had been linking with the leadership. Actually, even until

now, among Muslim municipalities like Shariff Aguak, it is

the Datu system that runs the community affairs. That is why,

there is truth when they say that there is no election in Shariff

Aguak. There is only selection. That was really the way

things were done in the Datu and Timuay systems. They

passed through the process where they were simply appointed

11

--------------------------------------------

and were not voted upon by the people. That was the system

we lived for a long time and was fully understood by even the

most ordinary of our people.

That is why today, even when somebody has been elected

as mayor or barangay chainnan, people still perceive of him

as Timuay (or Datu). Presently our mayor is a Teduray. One

of his difficulties lies in his inability to duplicate such kind of

relationship because he is not a Datu. In people's minds, that

was the standard transaction. It is not his fault if he could not

satisfy such expectation. He is sincere in trying to fulfill his

responsibilities and duties in the mainstream system. Some

people could not simply comprehend the mainstream system.

As of now, he is much pressured in finding a strategic

approach to this problem. Another thing, in the Teduray

society, we understand that we are all equal. There is no idea

of constituency. The leader simply facilitates the concerns of

the people. Aside from that, there is no hierarchical position.

This is the principal value in the establishment of the TJG

all are equal including the leader).

One of the questions in the FGD asked: "Sa ngayon, anu

ano ang mga nagiging problema ninyo sa pagpili ng inyong

fider? Papaano ninyo nabibigyan ng solusyon ang mga ito?

Anu-ano ang inyong mga rekomendasyon upang lalong

mapabuti and pamamalakad sa inyong komunidad?" (At

preosent, what problems do you encounter pertaining to

selection of a leader? How do you resolve these? What are

your recommendations in order to improve the management

in your community?).

The questions generated two types of answers. The tone

depended on the socio-political orientation of the participant.

Non-LGO (Local Government Officials) participants

recognized that, "Ang eleksiyon ay hindi naaangkop sa

sistema ng Tedw-ay" (Election [voting] is not compatible with

the Teduray system). In spite of this, it is worth noting that

many Teduray individuals have held government positions at

one time or another. On the other side, key infonnants

confidently expressed: "Sa akin lang, wala naman gaanong

problema. Ang mga maWt na gulo, mga Baglalan at

Kefedewan pa rin ang mag-solve. Pero ang logging, dahil

malaki na, sa munisipyo na ito dapat dalhin" (I think there is

no problem at all. It is still the Baglalan and Kefedewan who

settle small problems. Big problems such as the logging

operation should be brought to the municipal level).

In view of this general problem, they recommend the

recognition of the Teduray system of political ascendancy.

Furthennore, the recommendation includes the recognition of

the Teduray justice system where a community problem goes

through the deliberations of the Kefedewan within the

auspices of the Baglalan (title holders) and the Samfeton

(council of Kefedewan) before, if ever, reaching the barangay

chainnan. They believe this is more effective because, "Sa

mga Kefedewan at mga Timuay, inaayos talaga ang

problema. Napag-uusapan nila ang tamang penalty para

maayos ang problema" (Problems are really resolved at the

level of the Timuay and Kefodewan. It is where penalties are

justly determined in order to solve the problem).

The positions ofthe Tilnuay, Kefedewan, and Bfiyan have

been effectively sustained and kept alive in the present

context in spite of the imposition of the mainstream and

dominant Philippine governance system. But its traditional

socio-political schema has been dramatically altered. Todqy,

the provinces, municipalities, and barangays with very

different area delineation supercede what used to be

delineated as Inged (territories) and Fenuwo (villages)

relative to adjacent territories of other groups such as the

Arumanen, the Dulangan, and the Magindanaon.

Consequently, the Teduray who now live within this set-up

12 13

possess a mixed perception of the leadership structure. Very

often, ordinary Teduray folks today, inter-changeably refer to

the Timuay, Kefedewan, Fagilidan, Baglalan, Barangay

Kapitan, and Kagawad as The Leaders. However, when

pressed further about the traditional perception on leaders,

only the Timuay and Kefedewan surfaced as the prominent

generic traditional titles. The respondents did not recall of any

other leadership titles that have been handed down to their

awareness by their ancestors. This claim is very evident in the

way present Teduray communities operationalize the present

leadership set-up. Very often, the Barangay Kapitan

(barangay chairman) and Kagawad (barangay council

member) are also positions taken by Timuays or soon-to-be

Timuay. It is worth noting that, elected officials in the

municipalities and the barangays dominated by the Teduray

population are conferred with the Timuay titles.

It has been stressed that the primary problem with the

present system of selecting leaders is the 'palakasan'

(political patronage) system where a person, "Kahit hindi

qualified, basta nakasandal sa malaking politiko ay nagiging

lider. Hindi nakaka-unite sa tao. Hindi tuloy nag-cooperate

yung iba. Dinadaan sa threats. Sa barangay naman, kung

saan mixed ang grupo ng Teduray at settlers, at kung ang

lider ay settler, nagiging neglected ang Teduray. Madalas,

walang tsansa ang mga TedUl'ay na manalo sa election. May

11

discrimination. Madalas, kung sino ang may pera, ay siya

ang panalo sa eleksiyon" (Even non-qualified [persons], with

big politician backers, become leaders. But this results in

disunity. Consequently, others refuse to cooperate [with the

leadership]. Other [leaders] employ threats. In the barangay,

where there is mixed group of Teduray and 'settlers' , in

which the local official is a settler; the Teduray feels

neglected. Oftentimes, the Teduray has no chance of winning

the election. There is discrimination. Oftentimes, the one who

has the money wins the election).

14

In the present context, there is a general comfortable

feeling towards local governance because the current chief

executive of the municipality is a Teduray. However, there

exists an implied fear that the change of leadership can mean

problem to Teduray communities. A Key Informant pointed

that one obstacle to the satisfaction of Teduray concerns is,

"Kung magbago ang Mayor. Ngayon kasi, Teduray ang

mayor kaya kahit papaano, nabibigyan ng halaga ang mga

pangangailangan ng Teduray. Oras na mapalitan siya ng

hindi Teduray, sa palagay ko, maisasantabi na naman

kami" (If the mayor is changed. As of now, the mayor is a

Teduray so that, Teduray concerns are given attention. I

believe, the moment he is succeeded, we will be sidelined

again).

In addition, Teduray local government officials also

pointed the larger problem of non-recognition of the

Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997 (IPRA) in the

ARMM. A Department of Education (DepEd)-ARMM

official expressed that one big obstacle to Teduray concerns

is: "Kakulangan ng pagrespeto at pagkUala sa karapatan ng

mga katutubo. Kakulangan ng pagpapatupad ng batas IPRA

sa ARMM' (Lack of recognition and respect of IP rights.

Lack of implementation of the IPRA law within the ARMM).

Among them, there is insistence on recogmtIon of

traditional laws in the mainstream governance system, "Kung

ako lang, isang balakid ang di pagkilala ng gobyerno sa

tradisyunal na pamaraan namin. Para sa akin, mas epektibo

talaga para sa amin ang tradisyunal. Kaya sana, i-recognize

naman ng gobyerno ang aming pamaraan. Problema rin

namin ang logging. Sa ngayon, nandiyan pa rin sila. Pero di

namin sUa pinakialaman, basta lang huwag sUa pumasok sa

aming barangay" (In my opinion, one of the obstacles is non

recognition of our traditional ways by the government. I am

convinced that the traditional way is more effective to us. I

15

- - - - - - ~ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

wish the government will recognize it. Another problem is the

logging [operation]. Right now, they are still in the area, but

we don't do anything to them, as long as they don't encroach

into our barangay).

To these interrelated problems, they recommend the

recognition of the Teduray system stipulated in the Timuay

Justice and Governance (TJG). Accordingly, it is seen as an

opportunity to mainstream Teduray socio-cultural, political,

and economic issues.

The Timuay Justice and Governance of 2002

In 1993, the larger Teduray communities in the

municipalities of Upi, and Timanan, including the satellite

Teduray communities in Lebak, Kalamansig, Datu Odin

Sinsuat, Talayan, Shariff Aguak, Kulaman, and Ezperanza

undertook a tribal gathering and formed the Mamalo

Descendants Organization (MOO) basically to unite Teduray

communities under a common historical theme

2

They also

discussed and brought back memories of the traditional

Timuay leadership structure. Finally in 2002, they formalized

the revival of the traditional leadership structure into the

Timuay Justice and Governance (TJG). Timuay Alim Bandara

explained that the primary reason for the move was, " ... .

para maibalik sa isipan ng mga tao and dating istruktura .. .

( . ~ . to raise people's awareness about the traditional structure

of the Timuay leadership). The leaders explored ways how the

Teduray governance could be recognized. They drew their

ideas from the fact that the Timuay, Kefedewan, and Bliyan

are still very much alive in their collective consciousness

2 Common Teduray and Magindanaon legend tells of brothers Mamalo and

Tabunaway. Accordingly Tabunaway converted to Islam and became the

ancestor of the Magindanaon and other Islamized tribes. Mamalo chose to retain

his indigenous belief and decided to live in the mountains. He became the

ancestor of the indigenous tribes including the Teduray.

despite the domineering presence of the mainstream

governance system. And so, the collaborative effort to revive

the traditional leadership structure was pursued in earnest.

Their recognized community leaders, the elders, were

illiterate but very wise, and their active and educated youths

discussed, planned, and collaborated to draw up the current

structural design of the Timuay Justice and Governance.

Finally, they were able to establish the TJG. Presently, they

are advocating and looking for ways to have it recognized in

the regional government structure of the AR1v1M.

It is through the Mamalo Descendants Organization

(MOO) that The Timuay Justice and Governance (TJG) was

established in 2002 with the primary aim of strengthening

tribal governance and of putting up a governance structure

that is "interface-ready" with the government structure.

Internally, it is structured to facilitate greater community

participation in the overall consultation process of

governance. As explained, it embodies the traditional Teduray

concept of, "... istruktura ng pam'umunuan, mga batas,

polisiya at program a sa pamamahala" (leadership structure,

laws, and policies and programs of governance). Its

characteristics are founded on the traditional basic principles

of: close affinity with the natural environment, communal

ownership, collective leadership, equality of all human

beings, Kejiyo Fedew (harmony), and Lumot Minanga

(progressive pluralism). It is constituted by the following key

structural elements:

. . . Tim/ada Limud (tribal congress)

... Minted sa 1nged (Council of Chieftains)

... 1nged Kasarigan (territorial Executive Body)

... Fagilidan (supreme justices)

. . . Timuay Labi (Tribal Head Chieftain)

... Titay Bleyen (Vice-Tribal chieftain)

___________________________________ 17 16

Ayuno Tulos (secretary)

Senrukoy Tulos (Treasurer) (TJG, 2002,

pp.6-11).

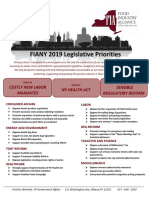

Figure 1: Structure of the Timuay Justice and Governance

PROVINCE/REGION

I

INGED KASARIGAN

rrerritory Executive Body)

1. Timvay Kasadgan

2. Sungku Timuay Kasarigan

3. Mumuuka Inged (territory

Overseer)

4. Far;uyaga

M.ginged(.griculture)

5. FUamallln (organizer)

6 Senrukuy Tulos(finance)

7. Kemem.1 K.adatan(spiritu.'

comrrittee, doctor. seer)

8. Civil Society Orgt niza/ions

9. Seayunon(/faison. spokes",.n)

10. Finl.ilan(Womenos group)

11. M.ngungud,(youths group)

12. Diy.g. Fenuwo(village police)

TIMFADA LlMUD

(Tribal Congress)

MINTED SA INGED

Administrative

Council of Chieftains

I . Timl'o/Labi (Tnbal Head

ClUeftain)

2.

J Ay""o T "las (.o::n,,,,y)

J. Sa>n<k0)' T"Ia. (Treasurcr)

5. Mi.wmb", (8)

.

SELIMUDO FENUWO

Local Council of Chieftains

I I

I I

I

Sitio

I I SitiD

I

KOYORAN (SITIO)

I

FAGILIDAN

(Supreme Jus1ices)

I Kefedewan

.

I

Fenuwo Executive Body

, . Tvnggv Kuarigan

2 Svngko Kasarig8n

I

I

Sitio I

Bibliography

Accion Contra EI Hambre (2005). Broken lives, fragile

dreams: A Vulnerability study of five ethnic

commumties in Maguindanao and Lanao del Sur.

Cotabato City: ACH.

Alejo, A. E. (2000). Generating energies in Mount Apo:

Cultural politics in a contested environment. Quezon

City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Convention (No. 169) Concerning Indigenous and Tribal

Peoples in Independent Countries (September 1991).

http://www.unhchr.chlhtml/menu3/b/62.htm

Datumanong, Abubacar M. (2005). The Maguindanaon

Datus: Their role in resolving conflict. Unpublished

Doctoral Dissertation. Notre Dame University,

Cotabato City

Gowing, P. & Mc Amis, R. (1974). The Muslim Filipinos.

Manila: Solidaridad Publishing House.

Hoebel, A. E. (972). Anthropology: The study of man. New

York: McGraw - Hill Book Company.

Hughes, L. (2003). The No-Nonsense guide to indigenous

peoples. Oxford: Verso.

Lacson, RD C. (2005). Aromanon Manobo armed conflict

experiences:

strategies. U

Philippines.

Cultural

npublished

coping

theses.

mechanisms

Xavier Unive

and

rsity,

19

MUNICIPAL

BARANGAY

I

Samfeton

(Fenuwo Justices)

1. Tvnggu Samfeton

2. Svngko Samfeton

REMFING FENUWO

(MUNICIPAL)

Remfong Fenuwo Ju";ces I Remflng F enuwo Kasangan

(Kefedewan)

l

Baglalan

J

Body)

(Executrve Body) I T;mv.y Kasarigan

2Svngku Kanrigan

I

I Sitio I

I,

18

Mastura, Michael O. (1979). The rulers of Mindanao in

modern history: 1515-1903. Research Proj ect No. 5

Modem Philippine History Program. Quezon City:

Philippine Social Science Council.

Mc Kenna, T. M. (1998). Muslim rulers and rebels. Manila:

Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Rodil, B. R. (1994). The minonttzation of indigenous

communities of Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.

Davao City: Alternate Forum for Research in

Mindanao, Inc.

Schlegel, S. (1970). Tiruray Justice. California: Berkley

University Press, Inc.

The World Bank (November 2003). Human development for

peace and prosgerity in the Autonomous Region in

Muslim Mindanao. Pasig City: The World Bank.

Tilnuay Justice and Governance (2003). Oryentasyon Hinggil

sa Timuay Justice and Governance. Quezon City:

Philippine Peasant Institute.

iJ

The Final Report of this research abstract is available at the University Research Center.

20

-- -

The University

has three service units: Sudo-Ec'OI loll lh' I<c 'sc 'U!'C'1I (SI':I<C);

Institutional Reseal'ch al\(I I )cwduI'lIIc 'III (11<1) ); IIml HIlIJIBull io. (UB).

With its multi-service ullits. I III lvc','slly

performs the NDlJ Visioll-Missioll to NIWVC' .. ... 111'1 II C'c'lIl,c' " 1"111' I lin

meeting and 1111111'111111 ", III<C'"" IIIUlUlulf'

is to promote the advUlHxmwlI1 or klluwlc'clgc' 111111 c!c 'VC'luIIIIH' 111 III

Central Mindanao alld AI<MM 11I1'CI1l1ol1i :111111111111.1

disciplinary Oil isSlws of d UllIgl ! 111111 ur

peoples in this parI. of Mir\(lall:lCl.

Slll( SOClo-ECONOMIC RESEARCH CENTER

('lIq.lql''' III ( UIl.lbOl.,llulI/ V.uU( IIMlury .u tlon

resea rches on issues of d('wlopnwlIl lo( "I ,HId ,,,,tloII.1I, of prlvc, t" and

public agencies/ instilutione; in Ikqinll XII (e ('utr.,1 Mlud.UMO) .1nd the

Autonomous Region in Mh"I,III.IO (ARMM) " rc.u Id,' ntlnr d In

the East Asean Growth Arc!., (f:AtiA) lJulVIIUII

INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH

AND DEVELOPMEN

serves as the reSt'tHeh .1I1e1 "I."mlm) ."rn of th" Unlv

providing assistance to Unlwl \lIy ",' ( 10f\ , II (un

researthes and planning dl'vclopl1U' nl J>l oqrdm, for l'l\tIluti onal

development.

DATABANK

DB

"

provides wll('( lion of f.u t,

regions of Mindanao, Pll rtJcul.lrly till' Autonomou

Mindanao (ARMM), Rcqlon XII (( ,' ntr .11Mlnd.",.,u)

It allows information J((rss dnd ,,,trlev.1

system with the Federi CO Aquino Intfmcl of N

http://www.nduJapcnclorg/urcdb/

Urdve.rsity

Cotabato City

Research Monograph No. 30

Self-Governance Practices

of the Teduray

This Research Monograph Series presents the

researches conducted by the University Research Center,

Notre Dame University, Cotabato City

You might also like

- Discovery of Cells and The Development of Cell TheoryDocument2 pagesDiscovery of Cells and The Development of Cell TheoryCed HernandezNo ratings yet

- The C-Value Paradox, Junk DNA, and ENCODEDocument6 pagesThe C-Value Paradox, Junk DNA, and ENCODEMartina RajnovicNo ratings yet

- Intervening VariableDocument32 pagesIntervening VariableJhedine Sumbillo - TabaresNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper On DreamsDocument4 pagesConcept Paper On DreamsCeline Calma100% (2)

- 1 Original ManuscriptDocument70 pages1 Original ManuscriptLuis RamosNo ratings yet

- A Quick and Simple FISH Protocol With Hybridization-Sensitive Fluorescent Linear Oligodeoxynucleotide ProbesDocument10 pagesA Quick and Simple FISH Protocol With Hybridization-Sensitive Fluorescent Linear Oligodeoxynucleotide ProbesNidhi JaisNo ratings yet

- Human Genome ProjectDocument5 pagesHuman Genome ProjectKyle Ambis SyNo ratings yet

- Origins of Life: A D D S C DDocument23 pagesOrigins of Life: A D D S C DjonasgoNo ratings yet

- Aryan Roots in Chinese .: Ede - InsDocument6 pagesAryan Roots in Chinese .: Ede - InsMario GriffinNo ratings yet

- Evolution First NoteDocument9 pagesEvolution First NoteTULSI SHARMANo ratings yet

- Lest We Forget! by Nicole Sadighi-Family Security Matters PDFDocument3 pagesLest We Forget! by Nicole Sadighi-Family Security Matters PDFnicolekian100% (1)

- Beginnings: 1.1 (Sorta) How Math WorksDocument11 pagesBeginnings: 1.1 (Sorta) How Math WorksBace HickamNo ratings yet

- Eternal LawDocument34 pagesEternal LawMaam PreiNo ratings yet

- Modern Synthetic TheoryDocument22 pagesModern Synthetic TheoryKamran SadiqNo ratings yet

- Fossil Mystery: Read The Short Story. Then Answer Each QuestionDocument4 pagesFossil Mystery: Read The Short Story. Then Answer Each QuestionULTRA INSTINCTNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Freedom: David MolineauxDocument2 pagesCosmic Freedom: David Molineauxsalomon46No ratings yet

- GR No 135385 PDFDocument94 pagesGR No 135385 PDFRanger Rodz TennysonNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 - Sociological PerspectivesDocument33 pagesLesson 3 - Sociological PerspectivesArianna NicoleNo ratings yet

- Advanced Powder TechnologyDocument11 pagesAdvanced Powder TechnologyDeepakrao Bornare PatilNo ratings yet

- Good Shepherd Cathedral MinistriesDocument41 pagesGood Shepherd Cathedral MinistriesomgpopNo ratings yet

- Ant 101: Introduction To Anthropology: Lecture 16: Human EvolutionDocument27 pagesAnt 101: Introduction To Anthropology: Lecture 16: Human EvolutionAmina MatinNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Revolutions That Defined Society: Reporters: Nathalie de Leon Dianne de Guzman BSBA 1-7Document15 pagesIntellectual Revolutions That Defined Society: Reporters: Nathalie de Leon Dianne de Guzman BSBA 1-7Fitz Clark LobarbioNo ratings yet

- 5 Ancient Theories On Origin of LifeDocument8 pages5 Ancient Theories On Origin of LifeNorberto R. BautistaNo ratings yet

- Molluscs in Mangroves PDFDocument12 pagesMolluscs in Mangroves PDFEnrique MartinezNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology and SocietyDocument40 pagesScience, Technology and Societygabbycervantes30No ratings yet

- Copernican TheoryDocument2 pagesCopernican TheoryAbigael JacobNo ratings yet

- Loss of Reading Habit Among The YouthDocument19 pagesLoss of Reading Habit Among The YouthDeepanjan Biswas100% (2)

- 1.the Science of EcologyDocument15 pages1.the Science of EcologyMerlito Fancubila Flagne Jr.No ratings yet

- Philo 1N BookDocument139 pagesPhilo 1N BookLuke BeanieNo ratings yet

- Magic and Medicine The Power of Seals IDocument6 pagesMagic and Medicine The Power of Seals Itroy thomsonNo ratings yet

- Crosswise Copy and AnswerDocument32 pagesCrosswise Copy and Answerflorie jane macayaNo ratings yet

- Human EvolutionDocument9 pagesHuman EvolutionVinod BhaskarNo ratings yet

- IucnDocument34 pagesIucnsaaisNo ratings yet

- Blue Miracle Super Liquid PDFDocument11 pagesBlue Miracle Super Liquid PDFJoseph Cloyd L. LamberteNo ratings yet

- Homo HabilisDocument3 pagesHomo HabilisGlutton ArchNo ratings yet

- Genomic Equivalence: DefinitionDocument5 pagesGenomic Equivalence: Definitionjgfjhf arwtrNo ratings yet

- Ecology A Branch of Biology (From Greek: "House" and "Study Of") Is TheDocument4 pagesEcology A Branch of Biology (From Greek: "House" and "Study Of") Is TheImmanuel HostNo ratings yet

- A Study On Relationship Between Academic Stress and Coping Strategies Among Adolescent BoardersDocument15 pagesA Study On Relationship Between Academic Stress and Coping Strategies Among Adolescent Boardersstefi5No ratings yet

- Genetic EngineeringDocument6 pagesGenetic Engineeringsarguss14100% (1)

- Nonvisual Photoreceptors of The PinealDocument36 pagesNonvisual Photoreceptors of The Pinealrambo_style19No ratings yet

- Summary of Laudato Si - NATRESDocument3 pagesSummary of Laudato Si - NATRESZarah Jeanine100% (1)

- A Newly Discovered Manuscript of The Hi PDFDocument29 pagesA Newly Discovered Manuscript of The Hi PDFCarlos VNo ratings yet

- Divine Law Theory & Natural Law TheoryDocument20 pagesDivine Law Theory & Natural Law TheoryMaica LectanaNo ratings yet

- Revealing The Hidden: The Epiphanic Dimension of Games and SportDocument31 pagesRevealing The Hidden: The Epiphanic Dimension of Games and SportXimena BantarNo ratings yet

- The Self From Various Philosophical Perspectives: Who Are You?Document7 pagesThe Self From Various Philosophical Perspectives: Who Are You?Donnalee NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Interrelationship of Political Science With Other Branches of LearningDocument2 pagesInterrelationship of Political Science With Other Branches of LearningJeffrey Calicdan Bucala100% (1)

- Tree of Life and SystematicsDocument10 pagesTree of Life and SystematicsRhob BaquiranNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 3 Intellectual Revolution That Define SocietyDocument27 pagesCHAPTER 3 Intellectual Revolution That Define SocietyYna Mae Sto DomingoNo ratings yet

- White Paper XIDocument21 pagesWhite Paper XIhola123456789jgNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Training FDocument9 pagesTransfer of Training FKerwin Misael HipolitoNo ratings yet

- Aristotle Four CausesDocument1 pageAristotle Four CausesMasoud NassorNo ratings yet

- STS Module 3A The Scientific Revolution (ACQUIRE)Document3 pagesSTS Module 3A The Scientific Revolution (ACQUIRE)GraceNo ratings yet

- Last Na TalagaDocument74 pagesLast Na TalagaJemica RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Trindade 2008: Reconciling Conflicting Paradigms: An East Timorese Vision of The Ideal StateDocument27 pagesTrindade 2008: Reconciling Conflicting Paradigms: An East Timorese Vision of The Ideal StateJosh TrindadeNo ratings yet

- LARMOUR - Culture and Democraty in The Pacific IslandsDocument13 pagesLARMOUR - Culture and Democraty in The Pacific IslandssutbangNo ratings yet

- Position PaperDocument5 pagesPosition PaperOOFOUCHIENo ratings yet

- Taylor E B 2009 Modern Dominicanidad Nat PDFDocument9 pagesTaylor E B 2009 Modern Dominicanidad Nat PDFJhoan Almonte MateoNo ratings yet

- Hirtz, Indigeneity, 2003Document29 pagesHirtz, Indigeneity, 2003cristinaioana56No ratings yet

- The Concept of Justice Among The Talaandig of LantapanDocument15 pagesThe Concept of Justice Among The Talaandig of LantapanTrishia Fernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Mou Forges Armm-Ipdev Cooperation: What'S Inside?Document12 pagesMou Forges Armm-Ipdev Cooperation: What'S Inside?IP DevNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 2-3Document15 pagesKetindeg 2-3IP DevNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 4Document11 pagesKetindeg 4IP Dev100% (1)

- Ketindeg 10 (Final Issue)Document56 pagesKetindeg 10 (Final Issue)IP DevNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Ritual For PeaceDocument2 pagesIndigenous Ritual For PeaceIP DevNo ratings yet

- DepEd Guidelines On The Conduct of Activities and Use of Materials Involving Aspects of Indigenous CultureDocument11 pagesDepEd Guidelines On The Conduct of Activities and Use of Materials Involving Aspects of Indigenous CultureIP DevNo ratings yet

- FADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFDocument9 pagesFADRHO - Conflict-Affected Fusaka Inged PDFIP DevNo ratings yet

- Program Flow RTD On The Promotion and Protection of IP Child and Maternal Health CareDocument1 pageProgram Flow RTD On The Promotion and Protection of IP Child and Maternal Health CareIP DevNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceDocument2 pagesThe Evolution of The Center of Teduray GovernanceIP DevNo ratings yet

- Ketindeg 9 - Vol 3 Issue 1Document17 pagesKetindeg 9 - Vol 3 Issue 1IP DevNo ratings yet

- 1st IP Cultural Festival Proposed Program FlowDocument1 page1st IP Cultural Festival Proposed Program FlowIP DevNo ratings yet

- Program Flow (Detailed)Document2 pagesProgram Flow (Detailed)IP DevNo ratings yet

- Invitation To EveryoneDocument1 pageInvitation To EveryoneIP Dev100% (1)

- Draft Implementing Rules & Regulations of RA 10368Document40 pagesDraft Implementing Rules & Regulations of RA 10368IP DevNo ratings yet

- Ubo Brief HistoryDocument15 pagesUbo Brief HistoryIP Dev100% (8)

- DepEd Order No.62, s.2011Document7 pagesDepEd Order No.62, s.2011IP Dev75% (4)

- IPDEV Data: Demographic Data of Lumads in Mainland ARMMDocument14 pagesIPDEV Data: Demographic Data of Lumads in Mainland ARMMIP DevNo ratings yet

- 154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao City 154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao CityDocument1 page154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao City 154 Mars ST., GSIS Heights, Matina, Davao CityIP DevNo ratings yet

- Đề 1. Ô tô trên cầuDocument29 pagesĐề 1. Ô tô trên cầuNguyen HoangNo ratings yet

- System". This Project Is A Web Based Application Developed in PHP and Mysql5 Xamp AsDocument23 pagesSystem". This Project Is A Web Based Application Developed in PHP and Mysql5 Xamp AsKeerthi Vasan LNo ratings yet

- Studying: Live Lesson NotesDocument12 pagesStudying: Live Lesson NotesHà MyNo ratings yet

- Cleveland 1-13 1Document2 pagesCleveland 1-13 1api-540028125No ratings yet

- Diploma in Mechanical Engineering by M SCHEMEDocument217 pagesDiploma in Mechanical Engineering by M SCHEMEMovies SpecialNo ratings yet

- The Young Crab and His Mother 3Document7 pagesThe Young Crab and His Mother 3Donnette DavisNo ratings yet

- Bader Abdul MajidDocument2 pagesBader Abdul Majidma saNo ratings yet

- Jay Adrian HGDocument5 pagesJay Adrian HGadrian lozano0% (1)

- Fia NyDocument1 pageFia NyThe Capitol PressroomNo ratings yet

- Phases in The Evolution of Public AdministrationDocument104 pagesPhases in The Evolution of Public Administrationaubrey rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Counseling ProcessDocument26 pagesCounseling ProcessAbang RamlanNo ratings yet

- Jenny JournalDocument27 pagesJenny JournalmaviinreyNo ratings yet

- English Exercise SheetDocument10 pagesEnglish Exercise SheetAndreea DemianNo ratings yet

- SHORT SD3-360 - SKYbrary Aviation SafetyDocument3 pagesSHORT SD3-360 - SKYbrary Aviation SafetyAnonymous d8N4gqNo ratings yet

- Home Invasion: Robbers Disclose What You Should KnowDocument19 pagesHome Invasion: Robbers Disclose What You Should KnowLittleWhiteBakkie100% (2)

- Pearson Test of English: Young LearnersDocument52 pagesPearson Test of English: Young LearnersGaolanNo ratings yet

- Indian Polity 10Document3 pagesIndian Polity 10Ramesh KurahattiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Factors in Choosing Location and Design of Port: Lecturer: Puan Umikalthum Binti ZulkeflyDocument8 pagesChapter 4: Factors in Choosing Location and Design of Port: Lecturer: Puan Umikalthum Binti ZulkeflyKausalya SankaranNo ratings yet

- Community HelpersDocument6 pagesCommunity HelpersLiz GardnerNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument20 pagesResearchjohn3ruiz3delfinNo ratings yet

- Christian Stokes Resume May20Document2 pagesChristian Stokes Resume May20api-510602244No ratings yet

- Courses: This Is Not An Official Academic RecordDocument2 pagesCourses: This Is Not An Official Academic RecordMartin GohNo ratings yet

- Nancy Beatriz Cahuana Saavedra Unidad 3Document3 pagesNancy Beatriz Cahuana Saavedra Unidad 3Jjeferson JavierNo ratings yet

- b-3087 Final Project ChoicesDocument3 pagesb-3087 Final Project Choicesapi-527115066No ratings yet

- Advanced Simulation of Rolling Element Bearings For Bearing Designers and Application EngineersDocument2 pagesAdvanced Simulation of Rolling Element Bearings For Bearing Designers and Application Engineersmohsin2014No ratings yet

- Eureka Math Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesEureka Math Lesson Planapi-479297618No ratings yet

- Super Six ParenthandoutDocument4 pagesSuper Six ParenthandoutNelson VersozaNo ratings yet

- Faizal Khan: Mobile +91 8291666788 - Email Id: Linkedin Profile: Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Willing To Relocate)Document2 pagesFaizal Khan: Mobile +91 8291666788 - Email Id: Linkedin Profile: Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Willing To Relocate)Faizal KhanNo ratings yet

- HR Docs & Templates - CompleteDocument8 pagesHR Docs & Templates - CompleteShahid Anwar50% (2)

- CNN Student News Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesCNN Student News Lesson PlanMegan CourtneyNo ratings yet