Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Road RIPorter 11.2 Summer Solstice 2006

Road RIPorter 11.2 Summer Solstice 2006

Uploaded by

Wildlands CPRCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Portland Maine METRO Westbrook Route 4Document2 pagesPortland Maine METRO Westbrook Route 4maxterryNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 16.1Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 16.1Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 13.2 Summer Solstice 2008Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 13.2 Summer Solstice 2008Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 10.4 Winter Solstice 2005Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 10.4 Winter Solstice 2005Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Quid Pro QuoDocument18 pagesQuid Pro QuoCCWebClientsNo ratings yet

- Wildlands CPR Issues New Report On Forest Service Road ManagementDocument24 pagesWildlands CPR Issues New Report On Forest Service Road ManagementWildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 3.3Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 3.3Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- EPA Dumps The Pumps: October 2008 Volume III Issue 3Document4 pagesEPA Dumps The Pumps: October 2008 Volume III Issue 3Gulf Restoration NetworkNo ratings yet

- RIPORTER 15.1 Single Pages-1Document25 pagesRIPORTER 15.1 Single Pages-1cathy1329No ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 2.2Document12 pagesRoad RIPorter 2.2Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Friends of The Flathead River, A Montana Nonprofit CorporationDocument16 pagesFriends of The Flathead River, A Montana Nonprofit CorporationNBC MontanaNo ratings yet

- WLP News No 26Document8 pagesWLP News No 26CCWebClientsNo ratings yet

- Victory On The Dead Zone: December 2009 Volume IV Issue IVDocument4 pagesVictory On The Dead Zone: December 2009 Volume IV Issue IVGulf Restoration NetworkNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 7.0Document20 pagesRoad RIPorter 7.0Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Special Places: Inside This IssueDocument12 pagesSpecial Places: Inside This IssueParksandTrailsNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Coastwatch: Stimulus Projects Strengthen CoastDocument8 pagesAtlantic Coastwatch: Stimulus Projects Strengthen CoastFriends of the Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletNo ratings yet

- Sep 2006 Mendocino Land Trust NewsletterDocument6 pagesSep 2006 Mendocino Land Trust NewsletterMendocino Land TrustNo ratings yet

- Is Cleaner Water in Florida's Future?: March 2010 Volume V Issue IDocument4 pagesIs Cleaner Water in Florida's Future?: March 2010 Volume V Issue IGulf Restoration NetworkNo ratings yet

- A Brief Introduction To Productive Environmental Law in The United StatesDocument13 pagesA Brief Introduction To Productive Environmental Law in The United StatesCharli ZernNo ratings yet

- January-February 2010 Echo Black Hills Audubon SocietyDocument10 pagesJanuary-February 2010 Echo Black Hills Audubon SocietyBlack Hills Audubon SocietyNo ratings yet

- Legal Notes: Logging Roads, Stormwater and The Clean Water ActDocument4 pagesLegal Notes: Logging Roads, Stormwater and The Clean Water Actcathy1329No ratings yet

- MNDNR 2022 Bonding FactsheetDocument2 pagesMNDNR 2022 Bonding FactsheetinforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Coastwatch: Flood Insurance Reform?Document8 pagesAtlantic Coastwatch: Flood Insurance Reform?Friends of the Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletNo ratings yet

- AECN 357 Exam 2 Short AnswerDocument3 pagesAECN 357 Exam 2 Short AnswerJayne DieterNo ratings yet

- A Study of The California Coastal Commission Prepared For Dr. Dan Moscovici Regional Planning Spring 2013 By: Matthew WardDocument12 pagesA Study of The California Coastal Commission Prepared For Dr. Dan Moscovici Regional Planning Spring 2013 By: Matthew Wardapi-253997878No ratings yet

- Pinelands Protection Act: BackgroundDocument3 pagesPinelands Protection Act: BackgroundAVNo ratings yet

- Environment Law AssignmentDocument35 pagesEnvironment Law AssignmentAnna OommenNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Coastwatch: Big Plans For "Forgotten" AnacostiaDocument8 pagesAtlantic Coastwatch: Big Plans For "Forgotten" AnacostiaFriends of the Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletNo ratings yet

- Jan-Feb 2003 Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletterDocument8 pagesJan-Feb 2003 Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletterFriends of the Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 5.3Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 5.3Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Worst Budget News Since The Early 1980 S!Document6 pagesWorst Budget News Since The Early 1980 S!Washington Audubon SocietyNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Coastwatch: Bombs Away at Bloodsworth?Document8 pagesAtlantic Coastwatch: Bombs Away at Bloodsworth?Friends of the Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 12.4 Winter Solstice 2007Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 12.4 Winter Solstice 2007Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- The Wildlands Project Unleashes Its War On Mandkind PDFDocument12 pagesThe Wildlands Project Unleashes Its War On Mandkind PDFMichael PetersenNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet 2Document6 pagesFact Sheet 2api-535392390No ratings yet

- A Wilderness Bill of RightsDocument8 pagesA Wilderness Bill of RightsPatrick Marvin BernalNo ratings yet

- Natural Heritage ConnectivityDocument3 pagesNatural Heritage Connectivitymitch9438No ratings yet

- Environment CRZDocument19 pagesEnvironment CRZDevesh SawantNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument20 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 11.1 Spring Equinox 2006Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 11.1 Spring Equinox 2006Wildlands CPR100% (1)

- Adirondack Land-Use Decisions Draw Praise and Criticism - Associated PressDocument3 pagesAdirondack Land-Use Decisions Draw Praise and Criticism - Associated PressDiane FishNo ratings yet

- Hobe Sound Currents December 2012 Vol. 2 Issue #10Document24 pagesHobe Sound Currents December 2012 Vol. 2 Issue #10Barbara ClowdusNo ratings yet

- Safe Passages: Highways, Wildlife, and Habitat ConnectivityFrom EverandSafe Passages: Highways, Wildlife, and Habitat ConnectivityNo ratings yet

- Senate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Public Lands and Forests BillsDocument81 pagesSenate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Public Lands and Forests BillsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument20 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NullDocument4 pagesNullapi-26026026No ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument22 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 2.3Document12 pagesRoad RIPorter 2.3Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 3.1Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 3.1Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Coastwatch: Daniel Island: The Community WinsDocument8 pagesAtlantic Coastwatch: Daniel Island: The Community WinsFriends of the Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletNo ratings yet

- Veto of Twin Metals Mining Leases Considered, Would Protect BWCAWDocument8 pagesVeto of Twin Metals Mining Leases Considered, Would Protect BWCAWFriends of the Boundary Waters WildernessNo ratings yet

- Winter 2003 Conservation Almanac Newsletter, Trinity County Resource Conservation DistrictDocument8 pagesWinter 2003 Conservation Almanac Newsletter, Trinity County Resource Conservation DistrictTrinity County Resource Conservation DistrictNo ratings yet

- Consumers Pay While Senator Gives Profits To Oil and Gas IndustryDocument11 pagesConsumers Pay While Senator Gives Profits To Oil and Gas IndustryProtect Florida's BeachesNo ratings yet

- Senate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Public Lands and Forests LegislationDocument81 pagesSenate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Public Lands and Forests LegislationScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Piedmont View Spring 2022Document8 pagesPiedmont View Spring 2022pecvaNo ratings yet

- The Roadrunner: Tejon Industrial Complex Development Hearing Tues. Jan 21. We Need You To Be There You Need To Know Why!Document8 pagesThe Roadrunner: Tejon Industrial Complex Development Hearing Tues. Jan 21. We Need You To Be There You Need To Know Why!Kern Kaweah Sierrra ClubNo ratings yet

- The Accidental Playground: Brooklyn Waterfront Narratives of the Undesigned and UnplannedFrom EverandThe Accidental Playground: Brooklyn Waterfront Narratives of the Undesigned and UnplannedNo ratings yet

- Final Draft SL Rise CoastalDocument21 pagesFinal Draft SL Rise Coastalapi-606503051No ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 18.1, Spring Equinox 2013Document20 pagesRoad RIPorter 18.1, Spring Equinox 2013Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Named Individual Members of The SAN ANTONIO Conservation Society v. The Texas Highway Department Et Al., and The U.S. Department of TransportationDocument12 pagesNamed Individual Members of The SAN ANTONIO Conservation Society v. The Texas Highway Department Et Al., and The U.S. Department of TransportationScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 6.6Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 6.6Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- RIPorter 17.3Document24 pagesRIPorter 17.3Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 18.2 Summer Solstice 2013Document19 pagesRoad RIPorter 18.2 Summer Solstice 2013Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 18.1, Spring Equinox 2013Document20 pagesRoad RIPorter 18.1, Spring Equinox 2013Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 16.1Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 16.1Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 7.4Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 7.4Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- 2009 Update: Six Strategies For SuccessDocument60 pages2009 Update: Six Strategies For SuccessWildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Wildlands CPR Issues New Report On Forest Service Road ManagementDocument24 pagesWildlands CPR Issues New Report On Forest Service Road ManagementWildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 8.2Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 8.2Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 9.1Document24 pagesRoad RIPorter 9.1Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 2.5Document12 pagesRoad RIPorter 2.5Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 2.3Document12 pagesRoad RIPorter 2.3Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 2.2Document12 pagesRoad RIPorter 2.2Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 2.6Document12 pagesRoad RIPorter 2.6Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 5.1Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 5.1Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 3.1Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 3.1Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 3.3Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 3.3Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 3.2Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 3.2Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 4.6Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 4.6Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 4.1Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 4.1Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 4.2Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 4.2Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 5.2Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 5.2Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 4.4Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 4.4Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- Road RIPorter 5.3Document16 pagesRoad RIPorter 5.3Wildlands CPRNo ratings yet

- TR 200MDocument12 pagesTR 200MMd Merajul Islam100% (1)

- Final Project Committed Cargo Care PVT LTDDocument115 pagesFinal Project Committed Cargo Care PVT LTDsnehsagar100% (1)

- Pavement Design Experimental Report Module J-01 Penetration of BitumenDocument11 pagesPavement Design Experimental Report Module J-01 Penetration of BitumenDian Ratri CNo ratings yet

- Report On Braking SystemDocument4 pagesReport On Braking Systemvaibhavporwal1No ratings yet

- Steel Design As Per Is 800-200Document2 pagesSteel Design As Per Is 800-200shri_12pNo ratings yet

- Integrated LogisticsDocument48 pagesIntegrated LogisticsAkshay RaharNo ratings yet

- Maps BhedaghatDocument11 pagesMaps BhedaghatCity Development Plan Madhya Pradesh100% (1)

- UAPCCD Planning Review NotesDocument85 pagesUAPCCD Planning Review Notesraegab100% (15)

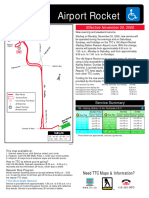

- 192 Airport Rocket (TTC)Document1 page192 Airport Rocket (TTC)renzoestores11No ratings yet

- Rail Safety & Standards BoardDocument19 pagesRail Safety & Standards BoardAndy AcousticNo ratings yet

- Carnewas at Bedruthan Coast Walk WalkingDocument2 pagesCarnewas at Bedruthan Coast Walk Walkingrayasander1No ratings yet

- Land Use - Transportation InteractionDocument12 pagesLand Use - Transportation InteractionAndrian AbanillaNo ratings yet

- List of East-West Roads in Toronto: Arterial Thoroughfares Canadian TorontoDocument20 pagesList of East-West Roads in Toronto: Arterial Thoroughfares Canadian TorontoOana RoxanaNo ratings yet

- Kapasitas Bucket PDFDocument9 pagesKapasitas Bucket PDFekoNo ratings yet

- TWV Conf - JLTV Breakout ChartsDocument12 pagesTWV Conf - JLTV Breakout ChartsJonNo ratings yet

- B3 G1 AimlDocument27 pagesB3 G1 Aimldihosid99100% (1)

- J. Tan Trucking Services: ChevronDocument15 pagesJ. Tan Trucking Services: ChevronJhon LazatinNo ratings yet

- Study of Mobility Impact Through Cable Car Implementation in Bandung, IndonesiaDocument121 pagesStudy of Mobility Impact Through Cable Car Implementation in Bandung, IndonesiaSheryta ArsalliaNo ratings yet

- History - WorksheetsDocument4 pagesHistory - WorksheetsMaria Jose FernandezNo ratings yet

- Drivers Manual Sample Test QuestionsDocument2 pagesDrivers Manual Sample Test QuestionsSheri BeamanNo ratings yet

- OffencesDocument10 pagesOffencesSubendu RakshitNo ratings yet

- Pres11e Tir Iru Item 15Document31 pagesPres11e Tir Iru Item 15Şhäbbîř ŞâďìqNo ratings yet

- Boston SubwayDocument1 pageBoston Subwayastec1234No ratings yet

- Tata Nano Problem StatementDocument5 pagesTata Nano Problem StatementKgp BaneNo ratings yet

- Nia Jasmine Reynolds v. City of New York, Et Al. (Second Amended Complaint)Document38 pagesNia Jasmine Reynolds v. City of New York, Et Al. (Second Amended Complaint)Eric SandersNo ratings yet

- 18Document31 pages18Fred LamertNo ratings yet

- Specification For Fabrication, Construction & Testing of Steel Pipe SystemDocument43 pagesSpecification For Fabrication, Construction & Testing of Steel Pipe SystemALINo ratings yet

- Fiat UlysseDocument254 pagesFiat UlysseDarko PavlovicNo ratings yet

- 7G 001 03 Technical Assurance PlanDocument39 pages7G 001 03 Technical Assurance PlanferryNo ratings yet

Road RIPorter 11.2 Summer Solstice 2006

Road RIPorter 11.2 Summer Solstice 2006

Uploaded by

Wildlands CPROriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Road RIPorter 11.2 Summer Solstice 2006

Road RIPorter 11.2 Summer Solstice 2006

Uploaded by

Wildlands CPRCopyright:

Available Formats

Summer Solstice 2006. Volume 11 No.

Mojave Riparian Recovery Threatened

By Daniel Patterson and Dan Funsch

The White Mountains of Mono Country, California. Photo by Daniel Patterson.

Inside…

Mojave Riparian Recovery Threatened, by Daniel Depaving the Way, by Bethanie Walder. Pages Policy Primer: Citizen Alternatives for Travel

Patterson and Dan Funsch. Pages 3-5 12-13 Planning, by Tim D. Peterson. Pages 18-19

Biblio Notes: The Impact of Roads on Aquatic Citizen Spotlight: Glen Jensen. Pages 14-15 Odes to Roads: The Deep Blue Breath of Wildness,

Benthic Macroinvertibrates, by Christine by Phil Condon. Pages 20-21

Get with the Program: Restoration and

Morris. Pages 6-8

Transportation Program Updates. Pages Around the Office, Membership Info. Pages 22-23

Regional Reports. Pages 9-11 16-17

Check out our website at: www.wildlandscpr.org

P.O. Box 7516

Missoula, MT 59807

I

(406) 543-9551

n April, Senator Conrad Burns (R-MT) introduced legislation to allow motorized access www.wildlandscpr.org

to 16 wilderness dams in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area along the Montana/

Idaho border (see alert on page 15). While the bill sounds outlandish, we must take Wildlands CPR works to protect and restore

this threat seriously. wildland ecosystems by preventing and

removing roads and limiting motorized

The threat is great for two reasons. First, in December 2004, Congress passed a law recreation. We are a national clearinghouse

to change wilderness boundaries to allow for road use. Second, during the past few years and network, providing citizens with tools

Congress has been passing comprehensive land management bills that threaten the con- and strategies to fight road construction,

cept of wilderness as places free from motors. Senator Burns’ bill is a real danger to one deter motorized recreation, and promote road

of the largest wilderness areas in the lower 48 states. removal and revegetation.

First, let’s look at the 2004 precedent. The Cumberland Island Wilderness is part Director

Bethanie Walder

of Georgia’s Cumberland Island National Seashore. This Wilderness Area was shrunk,

partially “un-designated,” by a bill that allowed motorized recreational access to historic

Development Director

sites. The “Cumberland Island Wilderness Boundary Adjustment Act” mandates that five

Tom Petersen

to eight round-trip rides be made available daily on two roads. It was passed as part of a

larger “must pass” appropriations bill, and it set a dangerous precedent.

Restoration Program

Coordinator

Second, several new land management bills (see RIPorter 9:4) (either proposed or en-

Marnie Criley

acted) contradict the traditional concept of designated wilderness under the Wilderness

Act. For example, three new “wilderness” bills in Colorado provide legislatively protected Science Coordinator

motorized recreation opportunities (outside of the wilderness boundaries). Numerous Adam Switalski

similar bills are currently being debated in Congress.

NTWC Forest Campaign

Burns wants to change the Bitterroot Coordinator

boundaries to allow maintenance at 16 dams Jason Kiely

that were constructed prior to the wilderness

designation. He claims the bill is solely for Transportation Policy

maintenance and safety, but it would exempt Coordinator

activities on the dams, lakes and rights of way Tim Peterson

from the National Dam Safety Program Act (as

Program Assistant

well as other environmental laws). The bill

Cathy Adams

would allow unlimited motorized travel along

the rights of way, not just motorized use for

dam maintenance. Newsletter

Dan Funsch & Marianne Zugel

In 1997 the Forest Service determined

Interns & Volunteers

that emergency measures were needed to

Anna Holden, Breeann Johnson,

make the Bass Creek dam safe, and they Tracy Jo Schweigert, Marlee Ostheimer

allowed water users to rebuild a road and

repair the dam with heavy equipment. The Board of Directors

agency has repeatedly made provisions for Amy Atwood, Greg Fishbein, Jim Furnish, William

motorized “emergency” dam access without Geer, Dave Havlick, Rebecca Lloyd, Cara Nelson,

special legislation. This bill is not justifiable, Sonya Newenhouse, Patrick Parenteau

it is simply a direct attack on The Wilderness

Advisory Committee

Act.

Jasper Carlton, Dave Foreman,

Keith Hammer, Timothy Hermach,

Senator Burns has feigned a safety con- Marion Hourdequin, Kraig Klungness, Lorin Lind-

cern while actually pushing motorized access ner, Andy Mahler, Robert McConnell, Stephanie

into this incredible wilderness. While the bill Mills, Reed Noss, Michael Soulé, Steve Trombulak,

is unlikely to pass Congress if debated on its Louisa Willcox, Bill Willers, Howie Wolke

Bass Creek dam, in the Selway-Bitterroot merits, if it were attached to an appropria-

Wilderness. Photo courtesy of Montana Trout. tions bill or some other must-pass legislation,

it could quickly become law. For more infor-

© 2006 Wildlands CPR

mation, see page 15 or visit our website.

2 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

“With Friends Like That...”

BLM Threatens<Mojave Riparian Recovery

By Daniel Patterson and Dan Funsch

F

or a few precious years, two of the nation’s finest

specimens of desert riparian area have been

protected from off-road abuse. In hard fought

battles that began nearly a decade ago, the Center

for Biological Diversity (“the Center”), Friends of the

Inyo, the Sierra Club of California, and their allies won

protections for the Mojave Desert’s Furnace Creek and

Surprise Canyon. Now, the Bureau of Land Manage-

ment (BLM), the Inyo National Forest, and a small but

vocal community of off-road enthusiasts are threaten-

ing the recovery of both these unique areas.

Furnace Creek drains the eastern side of the

magnificent White Mountains in Mono County, while

Surprise Canyon cascades down from the Panamint

Range of Death Valley National Park into the BLM

California Desert Conservation Area (CDCA) in Inyo

County. At the behest of off-roaders, BLM and the

Inyo National Forest are considering allowing off-

road vehicles to ‘mud bog’ in Furnace Creek and to

once again open Surprise Canyon to off-road vehicle

use. This would rewrite two success stories of desert

riparian restoration, and lead to the quick degradation

of water quality and wildlife habitat. The issue has

recently attracted the attention of California’s OHV

Commission, as well as California’s Senators Feinstein

and Boxer.

Furnace Creek Background

Furnace Creek is a beautiful perennial stream

draining the arid east side of the White Mountains, on

the boundary between the Mojave and Great Basin

deserts, containing some of California’s northernmost

Joshua Trees. This slow moving creek creates rare Looking up a waterfall along Surprise Canyon. Photo by Daniel Patterson.

desert wetlands and nurtures a mature forest of gigan-

tic cottonwoods and water birch thickets. It is home

to the Mono Basin sage grouse, which the Center has

petitioned for Endangered Species Act protection, in the early 80’s, but natural reclamation by willows, cottonwoods,

and is a rich part of the desert web-of-life. The area water birch, cattails and sedges was not enough to keep off-road

provides important habitat for neo-tropical migratory vehicles, jeeps & motorcycles out. Vehicles punched through the

birds, such as yellow and MacGillivray’s warblers, yel- creek, shrubs, bogs and all, leaving a muddy mess in their wake. Off-

low-breasted chats and lazuli buntings, and supports roaders wanted the road rebuilt, while conservationists argued the

marshes of cattails and sedges. The health of this area should be closed to off-road vehicles to facilitate the canyon’s

riparian area is also vital to local deer populations, natural recovery. In 2003, both the Inyo National Forest and BLM

raptors, mountain lions, bobcats, and quail. found that the off-road vehicle damage was legally unacceptable and

issued an interim closure for the area.

Furnace Creek’s lower section is within the BLM

California Desert Conservation Area (CDCA) and

managed by the BLM Ridgecrest Field Office, while its

upper length lies within the Inyo National Forest. An

old “road” up Furnace Creek washed out sometime — continued on next page —

The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006 3

— continued from page 3 —

Surprise Canyon Background

Like Furnace Creek, Surprise Canyon is managed by the Ridgecrest In 2000, the Center for Biological

BLM office as part of the CDCA. It the most productive spring-fed stream Diversity, Public Employees for Envi-

in the entire Mojave Desert: it is fed by Brewery Spring within Death ronmental Responsibility, and Sierra

Valley National Park, and Limekiln Spring. Surprise Canyon is home to Club filed a lawsuit against BLM in the

the endangered Inyo California towhee and endemic Panamint alligator Northern District of California, seeking

lizard, and it is potential habitat for endangered riparian obligate birds to close the canyon to off-road vehicles.

such as the Southwestern willow flycatcher and Least Bell’s vireo. Then in 2001, as part of a settlement

agreement, BLM published a protective

closure notice in the federal register,

which banned motor vehicle use in the

canyon at least until BLM completed

“Desert riparian lands should be conserved and its CDCA Plan amendment. The vehicle

restored, and protected in their natural state. Off- closures were to be a top option consid-

road vehicle recreation should not be expanded, ered by BLM in the CDCA Plan.

encouraged, or maintained in fragile desert riparian

Re-opening Old Wounds

landscapes...”

Recently, a handful of extreme

— California OHV Commission off-roaders started a move to again

open Surprise canyon to off-road traffic.

They hope to ride through and winch

up the waterfalls, despite the great

damage this would cause to natural

For years, BLM had allowed unregulated extreme off-road vehicle and recreational values. Many good-

use of Surprise Canyon. Off-road vehicles regularly winched-up water- sized riparian trees – cottonwoods and

falls, cut native vegetation and spilled oil & gas into the water. The dam- willows – would have to be removed.

age was so bad that at one point BLM stated: “The canyon riparian zone The Park Service and BLM are prepar-

currently does not meet the BLM’s minimum standards for a properly ing an Environmental Impact Statement

functioning riparian system due to soil erosion and streambed altera- (EIS) to address options for the area,

tions caused by off-highway vehicle use.” which will be presented in the form of

an amendment to the CDCA Plan. While

the Park Service appears to oppose

re-opening the area to off-roaders, BLM

seems intent on allowing the off-road

destruction.

In Furnace Creek, a similar initia-

tive by off-roaders would re-open the

area to allow “mud bogging,” where off-

road vehicles drive through fragile wet-

lands. This would impair water quality

and sensitive wildlife habitat and turn

back the clock on the natural restora-

tion that has been occurring since the

closure. The Inyo NF and Ridgecrest

BLM office are now considering options

for Furnace Creek. They released an

Environmental Assessment (EA) early

in 2006 and analyzed six alternatives to

either permanently close — or realign

and improve the road.

Rare desert stream beds at the mouth of Surprise Canyon. Photo by Daniel Patterson.

4 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

State Commission and U.S. Senators

Weigh In

The State of California addressed the issue

in late 2005 by adopting a new policy to protect

critically endangered desert streams. Recognizing

that desert riparian areas have declined by over

90 percent in California, the California Off-Highway

Vehicle Commission (OHV Commission) passed a

policy declaring:

“Desert riparian lands should be conserved

and restored, and protected in their natural state.

Off-road vehicle recreation should not be expanded,

encouraged, or maintained in fragile desert riparian

landscapes. It is the policy of the Commission that

absent extraordinary and demonstrable need, it

will not fund or support any grants or cooperative

agreements which will directly or indirectly encour-

age, increase, or maintain off-road vehicle use in or

through the bed, bank, or channel of any existing

desert riparian botanical area. The Commission

shall maintain a list of priority Desert Riparian lands

and shall evaluate the list at least every five years

to maintain the integrity of these protected areas.

The Division shall not solicit or approve any grant or

cooperative agreement which will develop or rees-

tablish off-road vehicle use in a desert riparian area

unless exempted from this policy by noticed vote of

the Commission.”

While the state OHV Commission does not have

management authority over either Furnace Creek or

Surprise Canyon, their strongly worded statement

lends support to the effort to protect these areas.

Shortly after the OHV Commission acted, BLM’s Cali-

Hikers take in the scenery along Furnace Creek. Photo by Daniel Patterson.

fornia Director wrote a letter opposing the policy.

Next to join the debate were California Sena-

tors Feinstein (D) and Boxer (D). In a letter in December 2005, they quiet for granted. They vow to take direct action if

requested that the BLM and the Park Service support the permanent necessary to keep off-road vehicles out of the canyon.

closure of Surprise Canyon above Chris Wicht Camp, the terminus of Please lend your support to the campaign to protect

an access road. Their letter cited the area’s “rare and remarkable” these unique areas by contacting the Center for Bio-

resources, the presence of endangered species, and the availability logical Diversity.

of alternative destinations for off-road vehicle riding. They also

pointed out that while the 1994 California Desert Protection Act For More Information

omitted a narrow “cherry stem” of the canyon from Wilderness des-

ignation, it did so to allow potential access to mining claims, not to Read the California OHV Commission Policy on

authorize recreational off-road vehicle use. Desert Riparian Areas: http://ohv.parks.ca.gov/default.

asp?page_id=24182

Help Protect These Desert Riparian Treasures For more information on Furnace Creek: http://

www.friendsoftheinyo.org/web-content/pages/furnace/

While awaiting the release of decision documents for the Fur- Furnacepage.htm

nace Creek Road Environmental Assessment (EA) and the Surprise Join the campaign by contacting the Center for

Canyon EIS, the Center for Biological Diversity is organizing allies Biological Diversity at 520.623.5252 or dpatterson@bio

and preparing for possible legal action should it be needed. The logicaldiversity.org

Center submitted joint comments on the Furnace Creek EA along

with the California Wilderness Coalition, Friends of the Inyo, and — Daniel R. Patterson is a Desert Ecologist with the

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. Meanwhile, Center for Biological Diversity. Dan Funsch is editor of

over near Surprise Canyon, the Center is working closely with local The Road RIPorter.

residents who realize that they cannot take clean water and natural

The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006 5

Bibliography Notes summarizes and highlights some of the

scientific literature in our 10,000 citation bibliography on the

physical and ecological effects of roads and off-road vehicles. We

offer bibliographic searches to help activists access important

biological research relevant to roads. We keep copies of most

articles cited in Bibliography Notes in our office library.

The Impact of Roads on Aquatic Benthic

Macroinvertebrates and Using Bioassessments as

Indicators of Stream Health

By Christine Morris

S

edimentation is widely acknowl- Roads are also respon-

edged as a major cause of deg- sible for chemical contamina-

radation of instream habitats tion of streams. For example,

(Wood et al. 2005). During rain storms Forrow and Maltby (2000)

and snowmelt, dirt and gravel roads investigated the mecha-

bleed sediment into ditches that often nistic basis for reduced

drain into streams. These roads are a leaf processing in a stream

major source of stream sediment loads, contaminated with motorway

especially harmful fine sediments, and (superhighway) runoff. They

roads contribute more sediment to found the feeding rate of

streams than any other land manage- Gammarus pulex (Amphipo-

ment activity (USDA 2000). Sedimenta- da), the dominant detrivore

tion is directly related to a decrease at the site, was significantly

in benthic macroinvertebrate density reduced downstream of the

and a change in diversity according motorway discharge. Ap-

to a number of studies. In this paper I proximately 70 percent of

review some of the impacts of sedimen- the reduction in feeding rate

tation on benthic invertebrates and ex- could be accounted for by

plain how examining macroinvertebrate the direct effects of exposure

diversity can help determine overall to contaminated sediment.

aquatic ecosystem health.

Increased stream temper-

ature and reduced dissolved

Overview of Impacts oxygen content of streams

Wood and Armitage (1997) define can also be attributed to road

four primary ways in which fine sedi- activities such as the clearing

ments impair macroinvertebrate diver- High school students learn the importance of

of stream-side vegetation and macroinvertebrates in stream monitoring. Photo by Adam

sity and health: 1) altering substrate the input of sediments. Fine Switalski.

composition and changing its suitability sediment reduces dissolved

for some taxa; 2) increasing drift due oxygen content of the affected stream as suspended solids absorb heat from sun-

to sediment deposition or substrate in- light and increase stream temperature. Temperatures greater than 21oC (70oF) can

stability; 3) affecting respiration due to severely stress most coldwater macroinvertebrates (Frondork 2001).

silt deposition on respiration structures

or low oxygen concentrations associ-

ated with silt deposits; 4) impeding Using Macroinvertebrates for Stream Assessments

filter feeding by increasing suspended Bioassessment of rivers and streams can reveal water quality and stream

sediment concentration, reducing the ecosystem impairment. Aquatic benthic macroinvertebrates are especially useful

food value of periphyton, killing aquatic indicators as each species has a specific tolerance for water conditions (Frondork

flora, and reducing the density of prey 2001). These aquatic biota are affected by the physical, chemical and biological

items. In addition, through drift caused conditions of the stream and may show impacts from habitat loss not detected

by scouring the streambed, macroinver- by traditional water quality assessments. As monitors of environmental quality,

tebrates can become more susceptible macroinvertebrates can reveal episodic as well as cumulative pollution and habitat

to predation or experience damaged alteration. The use of macroinvertebrates as bioindicators has been shown to be

respiratory systems (Newcombe and one of the most reliable and cost-effective assessment tools of water and habitat

MacDonald 1991). quality in streams throughout the world (King et al. 2000).

6 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

Macroinvertebrate assess-

ment is crucial for determining

aquatic ecosystem health in

roaded landscapes. The presence

of roads has been shown to be

highly correlated with changes in

species composition, population

sizes, and hydrologic and geomor-

phic processes that shape aquatic

and riparian systems (Trombulak

and Frissell 2000). Macroinverte-

brate diversity and abundance are

affected by roads; their physi-

cal and behavioral changes can

pinpoint sources of road-caused

habitat impact.

Various models have been

used to assess macroinvertebrate

response to road induced aquatic

changes. The heterogeneity of

stream ecosystems, the variable

responses of macroinvertebrates,

and the differences between Water quality degradation due to roads is not often apparent to the casual observer, so it is important to

agency models suggest that analy- rely on indicators such as macroinvertebrates. Photo copyright Mark Alan Wilson.

sis of the reference conditions and

the model used is essential in interpreting bioassessment acquisition and interpretation, state agencies use different

results. Though impact is evident, collaboration between methods and models to biologically assess water quality.

agencies and citizen scientist working groups to define model (Barbour et al. 1999).

standards is needed for remediation of problems indicated by

bioassessment results.

Multimetric Assessments

US EPA Region IV has suggested adopting national

EPT Index multimetric assessment methods, sharing information on suc-

The most general macroinvertebrate assessment model cessful approaches to decision criteria, developing regional

uses the EPT index. This index claims that although different reference conditions across political boundaries, and devel-

insect taxa vary widely in their sensitivity to sedimentation, oping shared ecological databases. They have also initiated

the taxa from the orders Ephemeroptera (E), Plecoptera (P), cooperative efforts to increase exchange of biological data in

and Trichoptera (T) behave similarly. However, a taxonomic shared ecoregions or basins. Conducting side-by-side assess-

group can exhibit a great deal of heterogeneity (Lenat et al. ments with multi-agency projects and using a single method

1981), so an assessment method like the EPT may be insensi- would also assist in stream classification and developing

tive to changes in species composition unless composition is regional reference conditions by ensuring that differences in

altered along with overall taxa richness (Hawkins et al. 2000). assessment results are a consequence of natural differences

in biotic communities and not investigator bias (Housten et

Multimetric and multivariate approaches can increase a al. 2002).

model’s accuracy. These models evaluate the sampled com-

munity by comparing observed conditions to what conditions

or taxa are expected to occur in the absence of disturbance. Conclusion

The sampling method is important to consider as well. Gradi- Roads cause a variety of impacts on stream ecosystem

ent sampling designs have been shown to be more sensitive health and water quality. The use of macroinvertebrate as-

and powerful statistically than designs based on random sessment can reveal these impacts if properly conducted.

allocation of samples (King et al. 2000). Careful environmental analysis of the site, data comparison

to reference sites and species-specific response models can

The type of model used in macroinvertebrate assessment provide accurate assessment of stream impairment and

significantly affects determination of water quality impair- can generate predictions of macroinvertebrate response

ment. Identifying the specific impact on a macroinvertebrate to road-caused impacts. Comparison of macroinvertebrate

population may also be difficult due to the geomorphological assessment results based on methods and models collected

and geochemical controls on the physical and chemical char- by various citizen groups and state agencies will facilitate an

acteristics of streams. Many of the environmental variables accurate understanding of road-caused impacts on stream

are interrelated (Griffith et al. 2001) and as a result, com- health.

munity assemblages will be correlated with these variables,

though species distributions may be directly affected by — Christine Morris is a graduate student in Environmental

only one or a subset of the variables (Griffith et al. 2001). In Studies at the University of Montana.

addition to the physical variations that may influence data — References follow on next page —

The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006 7

References King, R. S., K. T. Nunnery, and C. J. Richardson. 2000.

Macroinvertebrate assemblage response to highway

crossings in forested wetlands: implications for

biological assessment. Wetlands Ecology and

Barbour, M. T., J. Gerritsen, B. D. Snyder, and J. B. Stribling. Management 8:243-256.

1999. Rapid Bioassessment Protocols for use in Lenat, D., D. L. Penrose, and K. W. Eagleson. 1981. Variable

Streams and Wadeable Rivers: Periphyton, benthic effects of sediment addition on stream benthos.

macroinvertebrates, and fish. EPA 841-B-99-002. Second Hydrobiologia 187-194.

Edition. US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of McGurk, B. J., and D. R. Fong. 1995. Equivalent roaded area as

Water, Washington, DC. a measure of cumulative effect of logging. Environmental

Forrow, D. M., and L. Maltby. 2000. Toward a mechanistic Management 19(4):609-621.

understanding of contaminant-induced changes in Mebane, C. A. 2001. Testing bioassessment metrics;

detritus processing in streams: direct and indirect macroinvertebrate, sculpin, and salmonid responses

effects on detrivore feeding. Environmental Toxicology to stream habitat, sediment, and metals. Environmental

and Chemistry 19(8):2100-2106. Monitoring and Assessment 67:293-322.

Frondork, L. 2001. An Investigation of the Relationships Newcombe, C. P., and D. D. MacDonald. 1991. Effects of

between Stream Benthic Macroinvertebrate Assemblage suspended sediments on aquatic ecosystems. North

Conditions and their Stressors. Thesis for Virginia American Journal of Fisheries Management 11:72-82

Polytechnic Institute and State University. Trombulak, S. C. and C. A. Frissell. 2000. Review of ecological

Griffith, M. B., P. R. Kaufmann, A. T. Herlihy, and B. H. Hill. effects of roads on terrestrial and aquatic communities.

2001. Analysis of macroinvertebrate assemblages in Conservation Biology 14(1):18-30.

relation to environmental gradients in Rocky Mountain United States Department of Agriculture. 2000. Forest Service

streams. Ecological Applications 11(2):489-505. Roadless Area Conservation Rule: Final Environmental

Hawkins, C. P., R. H. Norris, J. N. Houge, and J. W. Feminella. Impact Statement.

2000. Development and Evaluation of Predictice models Wood, P. J., J. Toone, M. T. Greenwood, and P. D. Armitage.

for measuring the biological integrity of streams 2005. The response of four lotic macroinvertebrate taxa

Ecological Applications 10(5):1456-1477. to burial by sediments. Arch. Hydrobiology 163(2):145-

Housten, L., M. T. Barbour, D. Lenat, and D. Penrose. 2002. A 162.

mulit-agency comparison of aquatic macroinvertebrate Wood, P. J. and P. D. Armitage. 1997. Biological effects of

stream based bioassessment methodologies. Ecological fine sediment in the lotic environment. Environmental

Indicators 1(4):279-292 Management 21(2):203-217.

Hikers make their way along the spring-fed creek in Surprise Canyon. Photo by Daniel Patterson.

8 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

Forest Guardians Awarded New Federal Policy Aides States

Collaborative Road In Claiming Roads (RS 2477)

Decommissioning Grant Outgoing Interior Secretary Gale Norton signed a

“secretarial order” reinforcing states’ and counties’ rights

On Friday April 28th, a 15-member federal panel to claim roads on federal land as their own, and maintain

granted Forest Guardians $360,000 under the Col- or expand them. The policy will apply to roads on all

laborative Forest Restoration Program (Community public lands, including national parks and wildlife refuges.

Forest Restoration Act, Pub. L. No. 106-393) to decom-

mission and close excessive roads on the Santa Fe The order effectively repeals Bureau of Land Man-

National Forest in New Mexico. The Santa Fe National agement rules, which, since 1997, required states and

Forest has the highest road density of any forest in counties to show proof of construction in order to claim a

the Southwest Region. The federal grant is unique in road under RS 2477. Now, counties need only prove road

that it greatly expands the concept of forest restora- claims under state laws.

tion in the Southwest beyond tree-cutting.

Norton’s order reflects a court ruling last fall that

High road densities degrade water quality, com- upheld the rights of several Utah counties to grade roads

pact soils, fragment wildlife habitat, and contribute to across the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

fire ignitions during inappropriate weather conditions. Under the ruling, neither the state nor the federal govern-

The project will eliminate these negative conse- ment can act unilaterally in changing the size or use of a

quences, improving forest health and water quality for road.

downstream users such as land grant communities,

municipalities, acequia (irrigation) associations, and States’ rights advocates praise the policy as a vic-

acequia systems. tory for local control, while environmental groups are

concerned that the order will lead to increased devel-

Under the terms of the grant, Forest Guardians opment and access for off-road vehicle use on public

will work with several collaborators, including Billy lands. “There are red flags all over this,” said Southern

Cordova Logging Inc., Coronado High School, and the Utah Wilderness Alliance Director Heidi McIntosh. “The

Coyote Volunteer Fire Department to restore forests biggest red flag is that the trails and other routes that are

that were heavily logged and roaded over the last cen- now closed to vehicular traffic will be turned over to the

tury. The goal is to rehabilitate 20 miles and 10 stream counties, who will in turn try to turn them into highways.”

crossings. Road decommissioning and revegetation

is expected to cost $5,000 per mile and $3,000 per

stream crossing. The project will also help develop a No Progress In Snowmobile

sustainable forest restoration industry in the area.

Emissions Since 2001

A Yellowstone National Park study has concluded

that even the cleanest snowmobiles have failed to meet

projected improvements in emissions. The study dem-

onstrates that snowcoaches are up to 41 times cleaner

than the most environmentally-friendly snowmobiles in

the Park. Yellowstone asked snowmobile manufacturers

to reduce carbon monoxide emissions by 70 percent (rela-

tive to 1999 two-stroke engines), but no 2005 snowmobile

has met that goal.

Yellowstone National Park is working on an envi-

ronmental impact statement that will call for improved

technology, but many are unsure if snowmobile manufac-

turers can be made to comply. Emissions are expected to

improve when cleaner technologies are developed.

Off-road vehicle tracks in a high alpine meadow. Photo

courtesy of Forest Guardians of Santa Fe, NM. — see more updates on next page —

The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006 9

Victories

California’s Algodones Dunes Will Remain Protected

A federal court has ruled against an attempt by the Bureau of

Land Management (BLM) to rescind protection of the Algodones

Sand Dunes in southern California’s Sonoran Desert. The area is

home to several threatened and endangered species, including

Peirson’s milk vetch, desert tortoise, and flat-tailed horned lizard.

In 2000, 50,000 acres of the 180,000-acre dune area were set aside

and designated off-limits to off-road vehicle use. This reprieve has

allowed endangered wildlife to begin to recover. The BLM, however,

recently released a new plan for the dunes that would allow off-road

vehicles in protected areas. The Center for Biological Diversity and

other groups sued the agency.

The court ruled that BLM’s proposed management plan vio-

An ATV rider ignores an “area closed to motorized vehicles”

lated federal statutes including the Endangered Species Act and the sign. Photo courtesy of the Center for Biological Diversity.

National Environmental Policy Act. For now, these dune areas will

continue to be free of motorized use.

Proposed Off-Road Use Along

Gallatin National Forest May Alaska’s Dalton Highway

Decommission Old Logging Roads Struck Down

The Gallatin National Forest in Montana is proposing to decom- A bill that would have opened the land along

mission 47 miles of old logging roads and a 1.2 mile stretch of an Alaska’s Dalton Highway (see RIPorter 11.1) to off-road

unauthorized off-road vehicle route in the Bangtail Mountains, north- vehicle use died in the Alaska Legislature May 2nd.

east of Bozeman. The bill, sponsored by Rep. Ralph Seekins (R-Fair-

banks), would have allowed off-road vehicles and

Many of these roads cut through land formerly owned by Big snowmachines in the area. It generated firm opposi-

Sky Lumber. Forest officials have known for years that the roads are tion from a broad swath of Alaska interests, including

causing severe erosion, and that siltation in nearby streams is above the Northern Alaska Environmental Center, the North

allowable levels. Westslope cutthroat trout inhabit the area. The Slope Borough and the Alaska Trucking Association.

Forest Service now has the money for the project, and expects to get There was concern that motorized use in the area

started in the summer of 2006. Environmentalists and motorized use would have negative effects on wildlife, and could cre-

advocates seem to agree that the project is a good one. ate dangerous conditions for truckers using the road.

Similar proposals have been submitted in Alaska

several times before, without success. The proposal’s

Plan To Reopen Florida Forest To Off- sponsor vowed to resurrect the bill next year.

Road Vehicles Rejected

A plan submitted by Florida’s Southwest Division of Forestry to

allow off-road vehicle use in Southern Golden Gate Estates has been

rejected by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The 55,000-acre Es-

tates area is part of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan,

intended to mitigate some of the damage inflicted to the Everglades

for decades. The plan is overseen by the Army Corps of Engineers.

The Corps rejected the proposed re-opening of at least 12 miles

of trails to off-road recreation. Other proposals such as a shooting

range and cattle grazing were similarly rejected. The plan also gener-

Off-road vehicle scars on a vegetated sand dune,

ated criticism from the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The sensitive

Santa Fe National Forest. Photo by Chris Kassar,

area has been closed to off-road vehicle use for some time, but was Center for Biological Diversity.

previously a haven for off-road vehicle users and gun enthusiasts.

10 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

Alert

Burns’ Bill Threatens Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness

Legislation would allow more than

100 miles of road building, unlimited

motorized use.

Senator Conrad Burns (R-MT) has introduced

legislation (S.2633) that would allow dam owners in

Montana’s Bitterroot Valley to build roads and use

unlimited amounts of motorized equipment to access

and maintain 16 dams in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilder-

ness. The bill would allow roads to be built where

trails now exist in ten canyons, most of which are

entry points into the 1.3 million-acre Wilderness.

Burns’ bill would:

• Grant unrestricted rights-of-way (ROW) up

to 120 feet wide where trails now exist, and up to 500

feet from the high-water mark around the dams and

lakes. The bill allows dam owners to sell the ROW to

anyone, which could lead to resort home develop-

ment. A dam at the edge of Canyon Lake in the Selway-Bitterroot

• Exempt activities on the dams, lakes and Wilderness. Photo courtesy of Wilderness Watch.

rights-of-way from the Wilderness Act, National Envi-

ronmental Policy Act, National Dam Safety Program

Act, or any federal law to protect fish and wildlife or

maintain water quality. The bill would strike a blow to the Wilderness Act and could set

• Allow unlimited motorized travel along the the stage for road-building in other areas of the National Wilderness

rights-of-way and unlimited use of motorized equip- Preservation System. Furthermore, the bill is entirely unnecessary.

ment at the dams. The Wilderness Act recognizes valid rights of water users to main-

• Strip Forest Service jurisdiction from the tain dams in the Wilderness while preventing degradation of wilder-

lands and give it to the state. The dam owners would ness character. The Forest Service should assist water users in

not be liable for any claim or damage resulting from finding wilderness-compatible, non-motorized ways to maintain the

their operation of the dams, except where one could dams…as it has been done for the past 100 years.

prove negligence of the owner.

Contact Information

Take Action Now!

Senator ____________

United States Senate

Washington, DC 20510

• Write or call Senator Burns and tell (202) 224-3121 (Capitol Switchboard)

him what you think of his dam bill. Urge him to www.senate.gov

encourage the Forest Service and water users to

seek wilderness compatible, non-motorized solu- Representative ______________

tions. U.S. House of Representatives

• Write or call your own senators and Washington, DC 20515

congresspersons and make them aware of your (202) 224-3121 (Capitol Switchboard)

concerns. www.house.gov

For more information contact Wilderness Watch.

Visit their website at www.wildernesswatch.org.

The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006 11

Wildlands CPR Announces

A Road Runs Through It

By Bethanie Walder

I

t was almost exactly ten years ago

(August 1996) when the Wildlands

CPR board realized that we couldn’t

just focus exclusively on providing

activists with legal, scientific and tech-

nical information about roads and off-

road vehicles. We discussed how criti-

cal it is for people to understand WHY

roads have ecological and economic

costs, WHY we have too many roads

and not enough roadless lands; WHY

wildlands should be restored through

road removal; and WHY off-road vehicle

recreation is damaging. After all, if

people don’t understand why some-

thing is a problem, they are unlikely to

do anything about it.

That fall we launched an essay

section in our newsletter to start to

build real understanding about the

problems with roads and off-road

vehicles, and the opportunities for real

wildland restoration. Our first essay

was written by one of our advisory

board members, Howie Wolke. In his

essay, “Aliens Unlock Secrets of the

Road,” Howie theorized that if aliens

were observing the United States, “they

might easily conclude that roads – from

superhighways to bumpy dirt tracks

– have a deep religious significance to

our society. Why else would humans

crisscross the entire landscape with

them?” Later in his essay, he concludes

that our religious-like zeal to build

roads is driven by our desire to control

nature, “We fear what we can’t control, “Wilderness: A Reminder” is a wood engraving by Claire Emery.

and we can’t control nature without A Road Runs Through It: Reviving Wild Places is illustrated with

roads and their trappings.” Howie’s es- Emery’s stunning wood engravings. Emery is an artist and natural-

say was terrific, and it set the stage for ist who focuses on conveying the beauties and mysteries of nature

the next ten years of incredible essays through art and education. She has illustrated publications for

about the problems with roads and clients including W.W Norton, Montana Audubon, U.S. Forest

off-road vehicles, and the values and Service, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, California State Parks,

importance of watershed restoration,

Mountain Press, and Orion magazine. Visit her website at http://

roadless wildlands and more.

emeryart.com.

12 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

Several years ago, we started an ef-

fort to compile some of the best essays

into a collection that we could make

more widely available than our news-

letter. Last year we found a publisher,

Johnson Books, and the collection is

being published this summer. Entitled

A Road Runs Through It, it contains 28

essays from an amazing array of writ-

ers. Some of the essays are reprints

from our newsletters over the past ten

years. Some are reprints from other

books, and quite a few were written

just for this collection. Tom Petersen,

Wildlands CPR’s Development Direc-

tor, took on the task of shaping this

collection of essays into a meaningful,

coordinated book about roads, off-road

vehicles and watershed restoration.

For the past several issues of The Road

RIPorter we’ve been printing abridged

versions of these new essays, including

pieces by Phil Condon, Janisse Ray and

Dave Havlick. We’ve printed them to

tickle your interest, and we hope you’ll

pick up a copy of the book to read the

essays in their entirety. In addition

to those authors, the book contains a

foreward by Annie Proulx and essays by

Peter Matthieson, Barry Lopez, Edward

Abbey, Derrick Jensen, Stephanie Mills,

Mary Sojourner, Katie Alvord and many

more fine authors.

Several of these authors will host

readings in their home towns once the

book is published this summer. It’s our

hope that A Road Runs Through It will

help expand the debate around roads,

off-road vehicles and restoration. It

presents an opportunity for readers

To Purchase A Road Runs Through It:

to carefully consider the impacts our

actions have. As Howie said so many Call Johnson Books toll-free: 1.800.258.5830

years ago, “As society matures beyond Mention Wildlands CPR and get a 15% discount ($15 instead of $17.50)

its lingering frontier mentality, perhaps The book is also available on Amazon.com. While it may be less ex-

we’ll loosen our white-knuckled grip on pensive there, Wildlands CPR doesn’t make as much per book. So give

nature. Maybe we’ll realize that more Johnson Books a call to help support Wildlands CPR. Thank you!

roads (and dams, clearcuts, strip malls,

human protoplasm…) make our world

poorer, not richer. … Perhaps we’ll much needed work. We’ve seen the done to address road and off-road vehi-

begin to restore a balance, a life affirm- Park Service expand some of its road cle problems, we won’t be satisfied until

ing partnership with the world from removal programs, and we’ve seen a larger and broader number of people

whence we came. A much wilder world all three land management agencies understand WHY off-road vehicles and

than the one in which we now live.” consider new approaches to off-road roads are a problem. As Aldo Leopold

vehicle management (albeit significant once said, “recreational development is

And Howie’s right. Ten years ago flaws remain). Granted, funding for a job not of building roads into lovely

the National Park Service was the only forest restoration is currently tied up country, but of building receptivity into

agency routinely restoring wildlands by in nationwide debates over fire and the still unlovely human mind.” A Road

removing unneeded, ecologically-dam- logging, limiting investment in road Runs Through It attempts to build that

aging roads. In the time since, we’ve removal, but we’re working on that. receptivity, with thoughtful, provoca-

seen the Forest Service state that they tive and creative literary essays. We

should remove up to 186,000 miles of While it might be easy for a re- hope you enjoy reading it as much as

roads from national forest lands, and source organization like Wildlands CPR we’ve enjoyed putting it together.

we’ve seen them invest in some of that to focus our efforts on WHAT can be

The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006 13

The Citizen Spotlight shares the stories of some of the

awesome activists and organizations we work with,

both as a tribute to them and as a way of highlighting

successful strategies and lessons learned. Please

e-mail your nomination for the Citizen Spotlight to

cathy@wildlandscpr.org.

Citizen Spotlight on Glen Jensen

By Cathy Adams

I

n 1994 Glen Jensen bought 270 acres of land bordering Arkansas’ Ozark So fight it he did. First Glen prepared

National Forest. By 2003 he and his wife had saved up enough to build comments on the proposed trail. He learned

their dream home, planning to spend the rest of their lives enjoying the that motorized vehicle use would be un-

sights, sounds and solitude of nature. Then in June of 2005 Glen received a let- restricted, the Forest Service had funding

ter informing him that the Forest Service was proposing to designate 74 miles only for trail construction (not upkeep),

of trail in his backyard as off-road vehicle (ORV) routes; directly impacting a there would be no dedicated law enforce-

quality of life he spent more than a decade trying to build. ment, no published regulations for the area

and no dedicated management resources.

Glen’s time spent hunting, fishing and observing wildlife near his home “There’s only one Forest Service law enforce-

allows him to witness bear, deer, mountain lion and turkeys in their natural ment officer responsible for 450,000 acres

habitat. One of his favorite things to do is to listen to nature sounds, but Glen in three counties, he said ‘there’s no way he

says the noise and disturbance created by off-road vehicles cause the wildlife can police the activity.’” When Glen asked

to disappear. “From my experience, deer in the woods become completely about enforcement he was told the ATV clubs

nocturnal, the bear will move out and turkeys will nest elsewhere…I’ve seen would police themselves.

turkeys abandon nests due to off-road vehicle disturbance.”

Concerned about this and other issues,

Currently, some hunters and hikers use the 74 miles of trail, but the Glen commented that the proposed trail

trails are at least 30 years old, overgrown and have been mostly reclaimed along the north boundary of his property

by the forest. With all the downed trees and limited access, off-road vehicles would also disturb wildlife. He expressed

go somewhere else. But if the Buckhorn OHV Trail goes through the For- his concerns over the county road use and

est Service would clean up the old trails, create three miles of new trail and maintenance, trash dumping and littering,

construct three new trailheads — one of which would be 1.5 miles from the the project’s funding, maintenance and noise,

Jensen’s home. With the three county roads around his home creating a tri- dust and water quality impacts.

angle of access points, there would be a constant stream of off-road vehicles

near his property. “We live here because of the solitude and quiet. If the For- A few months later Glen received a Deci-

est Service puts an off-road vehicle track here it destroys our way of living. So sion Notice from the Forest Service with a

the only choice is to fight it or leave…and I don’t want to leave.” Finding of No Significant Impact. However,

they did consider the section of proposed

trail that ran along Glen’s northern property

boundary, and moved it farther north. While

Glen appreciated that, it was the only con-

cern they addressed, so he decided to file an

appeal and found an environmental law firm

to assist him.

While Glen waited for his appeal to be

processed, he researched more of the proj-

ect. He contacted organizations and individu-

als who commented on the original proposal.

He contacted his state senator, state repre-

sentative and Governor, and he called U.S.

Senators Mark Pryor (D) and Blanche Lincoln

(D). Sen. Pryor sent someone out to walk-

through Glen’s property and asked him to

put on paper what kind of proposal he would

accept should the project go through. Glen

decided he would like to see the trailhead

Glen after a successful hunt. proposed 1.5 miles from his home removed.

14 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

Senators Lincoln and Pryor both wrote

letters to the Forest Service relaying Glen’s

concerns.

Near the end of January 2006 Glen

received a letter stating that his appeal was

accepted and that he should receive a reply

within three months. One week later he got

another letter saying that the Forest Service

had decided to go forward with the project.

Glen called the Regional Office: “You told

me this would take until March. I thought

someone would come out to look at it…re-

view maps…and a few days later I receive

this letter? That shows me you didn’t review

my appeal.”

Undeterred, Glen researched further

and came across another project proposed

Off-road access points often become a conduit for the illegal dumping of garbage

for the same area: The Pine Mountain Dam.

and debris. Photo by Glen Jensen.

The dam would provide area residents a

year round supply of water to combat past

shortages. Glen compared maps and found This discovery gave Glen the new angle he needed. He found that Sen.

that the Buckhorn OHV Trail would cross the Lincoln got $100,000 appropriated for the dam and found that the Army Corps

river upstream of the proposed dam, which of Engineers had put up $350,000. Glen called State Representative Beverly

he thought could potentially have an impact Pyle (R) and asked her to send a letter about his findings. Glen also wrote to

on the water quality of Lee Creek, the source Michael Sanders, the supervisor of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forest. In

downstream residents were planning to use short order, Glen received a response from the Forest Service saying they

as their drinking supply. were pulling the Buckhorn OHV Trail project until further analysis could be

completed.

Glen was thrilled to get the news. Although the success was only tempo-

rary, Glen figured he had two to five years until the Forest Service could com-

plete another EA, and it bought him time to gain support from the community.

Glen’s advice: don’t give up. He participated in the comment period,

wrote an appeal, and did extensive research. He submitted a Freedom of

Information Act request to release the names of those who commented on the

proposal and to see the sources of project funding. He found out that only 39

people commented on the proposal, and he called them to try to collaborate.

Glen credits the non-profit environmental law firm, Wildlaw, for valuable as-

sistance, in particular, their publications that offered advice on Forest Service

regulations and how to prepare for litigation. Glen also recommends getting

on the Forest Service mailing list for projects in your area. “Don’t get taken by

surprise,” he says.

Glen’s inspiration comes from going out into the woods and listening to

nature’s sounds. “I go back and forth on the off-road vehicle trail and I some-

times think it won’t be that bad. But then I sit in the woods listening to the

birds and the squirrels…hear hens clucking on a nest behind me…and then I

hear a four wheeler four miles down the road…and that’s just one.”

Glen isn’t sure what the future holds for the Buckhorn OHV Trail. “If the

project goes through I will submit comments, file an appeal and go to federal

court if I have to. If it ends, well, then that’s it.” As of now Glen’s passion has

forced him to use his personal money to fight his cause, “Right now I’m trying

to sell 121 acres to fund this fight and I’m taking money out of my 401k to do

this.” But Glen believes it’s all worth it, “If they put the off-road vehicle trail

in I can’t hunt. I can’t hear the gobble of turkeys over the noise of off-road

vehicles. It will take away my freedom to pursue what I consider to be one of

Off-road impacts to soils, water and solitude are

the most important activities in my life.”

among Glen’s concerns. Photo by Glen Jensen.

— Cathy Adams is the Wildlands CPR Program and Membership Associate.

The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006 15

Transportation

Program Update

Wildlands CPR’s Transportation Program is

pleased to announce that we have awarded stra-

tegic mini-grants ($3,000-$5,000) to activists in the

thick of off-road vehicle planning. On-the-ground

fieldwork is expensive and difficult to fund, but

critical considering that desk-bound land managers

are often unaware of the devastating impacts that

unmanaged off-road vehicle use has wrought on

their watch.

Wildlands CPR was uniquely positioned to

dispense aid to groups working to restore na-

tive ecosystems and recreational balance on our

national forests, thanks to support from the 444S

Foundation. Wildlands CPR staff at a recent planning retreat. From left to right: Jason Kiely,

Marnie Criley, Tim Peterson, Bethanie Walder, Adam Switalski, Cathy Adams,

Early this spring, Wildlands CPR asked lo- Tom Petersen. Wildlands CPR photo.

cal conservation groups to submit proposals for

funding to advance both proactive and defensive

efforts to implement the new Forest Service off-road

vehicle rule. The response was overwhelming.

We received 22 proposals requesting about four Ecosystem Management Decision Support

times the funding we had to give. All the proposals

were excellent, and it was truly a heart-wrenching Workshop

process to decide who would make the final cut. In

the end, we chose to fund those groups that dem- Adam helped organize a Forest Service Regional Training

onstrated the closest adherence to our three goals: Academy workshop on using Ecosystem Management Decision

projects that will address immediate threats and Support (EMDS) in transportation planning. EMDS is a GIS-based

opportunities related to the implementation of the system that has been used as a transparent tool to prioritize

new Forest Service ORV rule in western national for- road removal and designate off-road vehicle routes. Fraser

ests; projects that will advance a proactive litigation Shilling (UC Davis), Brian Muller (CU Denver), and Paul Burgess

strategy to uphold the Executive Orders as forests (Redlands U) led the workshop along with Mark Jensen (FS Re-

begin to implement the rule; and projects that could gion 1 Analyst). The workshop was attended by about 25 people

test a proactive zoning approach to route designa- from the Forest Service, Washington Department of Natural

tion as part of the implementation of the new Forest Resources, Bureau of Land Management, University of Montana,

Service rule. Environmental Protection Agency, and private consultants.

We awarded mini-grants to Washington-based Information requests

Conservation Northwest, The Three Forests Coali-

tion (Utah) and Great Old Broads for Wilderness, Adam continues to provide citizens, activists, scientists, and

Los Padres Forest Watch in south central California managers with scientific information on roads, road removal, and

and The Upper Gila Watershed Alliance in New Mex- off-road vehicles. Recent information requests came from the

ico. In addition, we funded an independent project University of Uyo (Nigeria); Colorado Environmental Coalition;

to investigate the dubious legality of the notorious Utah State University; The Nature Conservancy; the Heritage For-

Paiute ATV system in central Utah. Please join with est Campaign; the Nez Perce Tribe; National Parks Conservation

us in wishing these groups a safe and productive Association; Five Valleys Land Trust; The Wilderness Society; and

field season! concerned citizens in the U.S. and Chile.

16 The Road-RIPorter, Summer Solstice 2006

NTWC Update

The Natural Trails & Waters Coalition has organized four workshops on “advocacy through authentic

collaboration” this quarter. The workshop prepares participants to (1) assess a forest’s goals and methods

for using authentic collaboration, (2) help design the process, and (3) effectively engage in that process,

condition their involvement, or choose not to participate at all. A balance of conservationists, off-roaders,

other recreationists, and agency staff have been invited to the workshops.

The Coalition secured a matching grant from the National Forest Foundation to organize these work-

shops once the Forest Service and BLM announced their intention to employ “collaboration” for many of

the scores of travel planning and off-road vehicle route designation processes that are expected to take

place in the coming years. We have partnered with grassroots conservation organizations who have hosted

the workshops and expert trainers from the University of Virginia’s Institute for Environmental Negotiation.

Wildlands CPR has also supported these workshops through issue expertise and representing the Coalition

at one workshop.

The first of these workshops were hosted by the Center for Biological Diversity and held in Flagstaff,

AZ (March 18) and in Albuquerque, NM (April 1). The California Wilderness Coalition hosted a workshop on

May 11 to in Sacramento. Friends of the Routt Backcountry, a member of the Backcountry Snowsports Alli-

ance, hosted the Steamboat Springs workshop on May 13.

Nearly 100 people have attended the workshops so far, including two dozen Forest Service staff, dozens

of off-road vehicle users, quiet recreationists, and conservationists. One outcome from the New Mexico

workshop, for example, is that the 13 conservation/quiet recreation groups who attended have now formed

a statewide coalition to address off-road vehicle issues. The Center for Biological Diversity is coordinating

this new effort, with help from the Natural Trails and Waters Coalition.

Wildlands CPR staff will represent the Coalition at the next workshop, to be held on July 15 in Salt Lake

City. The Coalition will arrange for up to three more collaboration workshops in the coming months.

Restoration Program Update

The Restoration Program has been in high gear this Nationally, Marnie and the National Forest Restoration

spring on the local, regional and national levels. Locally, Collaborative are planning a trip to Washington DC in late

Marnie devoted time to the Governor’s Restoration Forum in July to meet with public land agency personnel about col-

Billings, Montana June 8-9. Montana’s Gov. Brian Schweitzer laborative restoration efforts related to roads, weeds and fish.

is very interested in pursuing a restoration economy, and This trio will focus on successful collaborative efforts that go

Marnie worked with members of his staff to help coordinate beyond just logging and fire issues.

this Forum. One key theme of the event was investing in

restoration work in Montana. Wildlands CPR intern Breeann Citizen Science on the Clearwater National

Johnson finalized a paper that addresses this issue, and Mar-

nie presented the paper at the Restoration Forum. More than Forest

300 people attended the extremely successful event.

Adam continues to support citizen science monitoring

Regionally, Marnie continues her involvement with the on the Clearwater National Forest, working with Len Broberg

Hells Canyon Collaborative. The Collaborative finalized a (University of Montana Environmental Studies Director) and

charter and is now focusing its attention on roads analysis Anna Holden (UM graduate student and Volunteer Coordina-

and transportation planning. Wildlands CPR will bring Fraser tor). Adam helped Anna develop outreach materials, increase

Shilling to the next collaborative meeting on June 20 (Fraser recruiting, and prepare for teaching at Kamiah High School.

has utilized the Ecosystem Management Decision Support Anna’s abstract was accepted for an oral presentation at the

System (EMDS) to conduct roads analysis on the Tahoe Society for Conservation Biology’s (SCB) annual meeting in

National Forest). It is possible the Forest Service, with as- San Jose, CA this summer. She will present methods for orga-

sistance from the Collaborative, will utilize EMDS to conduct nizing citizen science volunteers, as well as some preliminary

transportation planning and roads analysis within the Hells monitoring results. Adam is helping her key out tracks and

Canyon National Recreation Area. Marnie also led a success- analyze data for the presentation. For more information or

ful roads workshop for the Northeast Washington Forestry to get involved, contact Anna at: clearwaterroads@wildlands

Coalition, which is in the process of writing a collaborative cpr.org.

roads policy for the Colville National Forest.