Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Basal Cell Carcinoma: General Features

Basal Cell Carcinoma: General Features

Uploaded by

Sel ViaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Basal Cell Carcinoma: General Features

Basal Cell Carcinoma: General Features

Uploaded by

Sel ViaCopyright:

Available Formats

BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

GENERAL FEATURES BCC is the most commonest human malignancy and typically affects elderly patients. Important risk factors are fair skin, inability to tan and chronic exposure to sunlight. Ninety per cent of cases occur in the head and neck and about 10% of these involve the eyelid. BCC is by far the most prevalent malignant eyelid tumour, accounting for 90% of all cases. The majority arise from the lower eyelid, followed in relative frequency by the medial canthus, upper eyelid and lateral canthus. The tumour is slow growing and locally invasive but non-metastasizing. Tumours located near the medial canthus are more prone to invade the orbit and sinuses, and are more difficult to manage than those arising elsewhere and carry the greatest risk of recurrence. Tumours that recur following incomplete treatment tend to be more aggressive and difficult to treat.

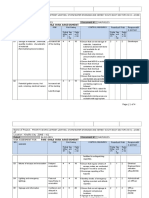

HISTOLOGY The tumour arises from pluripotent basal cells of the epidermis. The cells proliferate downwards (fig.4.20a) and exhibit palisading at the periphery ((fig.4.20b). Squamous differentiation with the production of the keratin results in a keratotic type of BCC. There can also be sebaceous and adenoid differentiation with the development of cystic and adenoid cystic types, while the growth of elongated strands and islands of cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma results in a sclerosing (morphoeic) tumour.

CLINICAL TYPES NB : The main clinical features of epidermal malignancy are ulceration, lack of tenderness, induration, irregular borders and destruction of lid margin architecture. 1. Nodular Nodular BCC is a shiny, firm, pearly nodule with small dilateral blood vessels on its surface, initially, growth is slow and it may take the tumour1-2 years to reach a diameter of 0.5 cm (fig. 4.20c). 2. Noduloulcerative

Noduloulcerative (rodent ulcer) has central ulceration, pearly raised edges (fig. 4.20d) and dilated and irregular blood vessels (telangiectasis) over its lateral margins (fig. 4.20e); with time it may erode a large portion of the eyelid. 3. Sclerosing Sclerosing BCC (morphoeic) is less common and may be difficult to diagnose because it infiltrates laterally beneath the epidermis as an indurated plaque (fig. 4.20f). The margins of the tumour may be impossible to delineate clinically and the lesion tends to be much more extensive on palpation than inspection. On cursory examination a sclerosing BCC may simulate a localized area of unilateral chronic blepharitis. 4. Other types Other types of BCC not usually found on the lid are cystic, adenoid, pigmented and multiple superficial. NB : Patients with BCC frequently show signs of actinic damage of facial skin.

TREATMENT 1. Biopsy The two types of biopsy are incisional, in which only part of the lesion is removed, and excisional, in which the entire lesion is removed. The two types of incisional biopsy are: a. Shave Shave biopsy is performed with a knife and involves removal of the superficial part of the lesion. It may be used in the diagnosis benign lesions but is not appropriate if malignancy is suspected. b. Punch Punch biopsy is performed using a skin dermatome similar to a corneal trephine. Histological examination of the deep part of the lesion is possible. 2. Surgical excision The entire tumour should be removed with preservation of as much of normal tissued as possible. Most small BCC can be cured by excision of the tumour together with a 4mm margin of tissue which looks clinically normal. More radical surgical excision is required for

large BCC and aggressive tumours such as SCC and SGC. Frozen section control by either a standard method or micrographic surgery can further improve the success rate. a. Standard frozen section involves histological examination of the margins of the excised specimen at the time of surgery to ensure that they are tumour-free. b. Mohs micrographic surgery involves excision with opertative analysis of serial horizontal frozen sections from the under-surface of the tumour. The sections are then colour coded or mapped to identify any remaining areas of tumour. Although time-consuming, this maximizes the chances of total tumour excision with animal sacrifice of normal tissue. This is a particularly useful technique for tumours that grow diffusely and have indefinite margins with finger-like extensions, such as sclerosing BCC, SCC, recurrent tumours and those involving the medial or lateral canthi. 3. Reconstruction The technique of eyelid reconstruction depends on extent of tissue removed and whether it is full-thickness. It is important to reconstruct both anterior and posterior lamellae. If one of the lamellae has been sacrificed during excision of the tumour, it must be reconstructed with similar tissue. Anterior lamellar defects may be closed directly or with a local flap or skin graft. Full-thickness defects may be repaired as follows: 1) Small defects involving less than one-third of the eyelid can usually be closed directly, provided the surrounding tissue is sufficiently elastic to allow approximation of the cut edges (fig. 4.27). If necessary, a lateral cantholysis can be fashioned to mobilize additional tissue if the defect cannot be reapproximated 2) Moderate size defects involving up to half of the eyelid may require a Tenzel semicircular flap for closure (fig. 4.28). 3) Large defects involving over half of the eyelid may be closed by one of the following techniques: a. Posterior lamellar reconstruction may involve an upper lid free tarsal graft, buccal mucous membrane or upper lid free tarsal graft, buccal mucous membrane or hard palate graft, or a Hughes flap from the upper lid (fig. 4.29). b. Anterior lamellar reconstruction may involve skin advancement. A local skin flap or a free skin graft (fig. 4.30). 4. Radiotherapy 1) Indications

a. Small BCC which does not involve the medial canthal area in patients who are either unsuitable for or refuse surgery. b. Kaposi sarcoma because it is radiosensitive. 2) Contraindications a. Medial canthal BCC because radiotherapy would damage the canaliculi and result in epiphora. b. Upper eyelid tumours because subsequent keratinization results in a chronically uncomfortable eye. c. Aggressive tumours such as sclerosing BCC, SCC and SGC. 3) Complications a. Skin damage and madarosis. b. Nasolacrimal duct stenosis following irradiation to the medial canthal area. c. Conjunctival keratinization, dry eye, keratopathy and cataract c. Retinopathy and optic neuropathy.

NB : Many of these complications can be avoided if the globe is protected by a special eye shield during irradiation. However, the recurrence rate is higher than after surgery, and radiotherapy does not allow histological confirmation of tumour eradication. Recurrences following radiotherapy are difficult to treat surgically because of the poor healing properties of irradiated tissue. 5. Cryotherapy 1) Indications. Small superficial BCC 2) Contraindications are similar to those of radiotheraoy, although cryotherapy may be a useful adjunct to surgery in patients with epibulbar pagetoid xtentions of SGC, thus spaing the patient an extenteration. 3) Complications are skin depigmentation, madarosis and conjunctival overgrowth.

6. Laissez-faire The wound edges are approximated as far as possible and the defect is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. Even large defects with time can achieve a satisfactory outcome.

You might also like

- Fire Risk Assessment-Rev 001Document5 pagesFire Risk Assessment-Rev 001ramodNo ratings yet

- Argelander Initial InterviewDocument13 pagesArgelander Initial InterviewTiborNo ratings yet

- Archery Kim Hyun TakDocument88 pagesArchery Kim Hyun TakKHAIRAN100% (3)

- Raid Leader's HandbookDocument56 pagesRaid Leader's HandbookJohnNo ratings yet

- API 5l x42 Pipe Specification Data SheetDocument1 pageAPI 5l x42 Pipe Specification Data SheetIván López PavezNo ratings yet

- Uhone Broker GuideDocument28 pagesUhone Broker Guidestech137No ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Malignant Tumors of The Eyelid, Conjunctiva, and OrbitDocument16 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Malignant Tumors of The Eyelid, Conjunctiva, and OrbitCici MutiaNo ratings yet

- Premalignant and Malignant Skin DiseasesDocument25 pagesPremalignant and Malignant Skin Diseasesmedical1acc2No ratings yet

- Ba So CelularDocument13 pagesBa So CelularMihaela BubulacNo ratings yet

- Akin CancerDocument7 pagesAkin Cancerucul8No ratings yet

- Tumores ConjuntivalesDocument5 pagesTumores ConjuntivalesElsa CabreraNo ratings yet

- Data SCC From InternetDocument3 pagesData SCC From InternetristaniatauhidNo ratings yet

- 2.11.1 Benign and Malignant Skin LesionsDocument14 pages2.11.1 Benign and Malignant Skin LesionsZayan SyedNo ratings yet

- Eyelid and Ocular Surface Carcinoma: Diagnosis and ManagementDocument11 pagesEyelid and Ocular Surface Carcinoma: Diagnosis and ManagementGlauce L TrevisanNo ratings yet

- CorrespondenceDocument2 pagesCorrespondenceash-syafi'eNo ratings yet

- Tumours of Skin: DR F Bhatti Pennine VTS Sept 08Document39 pagesTumours of Skin: DR F Bhatti Pennine VTS Sept 08pfxbkNo ratings yet

- Ophtha NotesDocument4 pagesOphtha NotesPeter GirasolNo ratings yet

- Modified Rhomboid Flap For Facial ReconstructionDocument3 pagesModified Rhomboid Flap For Facial ReconstructionahujasurajNo ratings yet

- ICO Cases AnswerDocument128 pagesICO Cases AnswerAmr AbdulradiNo ratings yet

- An Uncommon Cancer of Parotid Squamous Cell HistologyDocument3 pagesAn Uncommon Cancer of Parotid Squamous Cell HistologyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- PATHOLOGYDocument188 pagesPATHOLOGYMaisha Maliha ShamsNo ratings yet

- PathologyDocument58 pagesPathologysankethg93No ratings yet

- Epidermal Nevi, Neoplasms, and CystsDocument106 pagesEpidermal Nevi, Neoplasms, and CystsmesNo ratings yet

- CASE Report Basal Cell Carsinoma of NoseDocument22 pagesCASE Report Basal Cell Carsinoma of NoseDestar Aditya SadegaNo ratings yet

- Lembi CutaneiDocument6 pagesLembi CutaneiGianfranco MuntoniNo ratings yet

- Surgical Removal of MolesDocument4 pagesSurgical Removal of Moleskahkashanahmed065No ratings yet

- Anatomoclinical Confrontation Between Melanoma, Solar Lentigo and Seborrheic Keratosis: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesAnatomoclinical Confrontation Between Melanoma, Solar Lentigo and Seborrheic Keratosis: A Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Successful Reconstruction Using Three Flaps Combina 2024 International JournDocument7 pagesSuccessful Reconstruction Using Three Flaps Combina 2024 International JournRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- 21 SkinDocument18 pages21 SkinMahmoud AbuAwadNo ratings yet

- Fatal Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Evolving From A Localized Verrucous Epidermal NevusDocument11 pagesFatal Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Evolving From A Localized Verrucous Epidermal NevusHadi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- Chap2 PDFDocument20 pagesChap2 PDFwillyoueverlovemenkNo ratings yet

- TumourDocument7 pagesTumourعلي احمد جواد حسينNo ratings yet

- Cutaneous Squamous Cell CarcinomaDocument43 pagesCutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomapedrixon123No ratings yet

- Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (CSCC) : Clinical Features and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument55 pagesCutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (CSCC) : Clinical Features and Diagnosis - UpToDateSilvia Rodriguez PitreNo ratings yet

- Reconstructive Rhinoplasty in Cases With Basal Cell Carcinoma of The NoseDocument6 pagesReconstructive Rhinoplasty in Cases With Basal Cell Carcinoma of The NoseRaisa KhairuniNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Lacrimal Gland TumorsDocument6 pagesSurgical Management of Lacrimal Gland TumorsRochnald PigaiNo ratings yet

- Eyelid Cancer by Skin Cancer FoundationDocument5 pagesEyelid Cancer by Skin Cancer Foundationamrita90031No ratings yet

- Hannoun 2021Document4 pagesHannoun 2021mahaaNo ratings yet

- MCQin OphthalmologyDocument108 pagesMCQin OphthalmologyWeiting SONGNo ratings yet

- Knottenbelt - Et - Al-2018-Equine - Veterinary - Education (1) (2) (18972)Document12 pagesKnottenbelt - Et - Al-2018-Equine - Veterinary - Education (1) (2) (18972)Alan Rdz SalasNo ratings yet

- Debulking Surgery On Recurrent Dermal Neck Tumor Above Stoma After Total LaryngectomyDocument9 pagesDebulking Surgery On Recurrent Dermal Neck Tumor Above Stoma After Total LaryngectomyTeuku Ahmad HasanyNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery Case ReportsDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery Case ReportsRatna LuthfiaNo ratings yet

- Seminar Presentation On Common Skin Tumors: - Mekonnen (RII) - Moderator Dr. Teka Consultant Surgeon)Document61 pagesSeminar Presentation On Common Skin Tumors: - Mekonnen (RII) - Moderator Dr. Teka Consultant Surgeon)moges beletachawNo ratings yet

- Utilizing Free Skin Grafts in The Repair of Surgical Wounds: Madalene C. Y. HengDocument11 pagesUtilizing Free Skin Grafts in The Repair of Surgical Wounds: Madalene C. Y. HengDefri ChanNo ratings yet

- Common Conjunctival LesionsDocument4 pagesCommon Conjunctival LesionsSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Ormond 2013Document12 pagesOrmond 2013Hafiz AlfarizieNo ratings yet

- Crawley 2015Document6 pagesCrawley 2015Eduardo HernándezNo ratings yet

- Basal Cell Carcinoma Head and Neck: DR - Lakshmi MenonDocument34 pagesBasal Cell Carcinoma Head and Neck: DR - Lakshmi MenonlakshmiNo ratings yet

- Vulvar ProceduresDocument14 pagesVulvar Proceduresjft842No ratings yet

- SCC 2Document23 pagesSCC 2rizka hastariNo ratings yet

- Carbuncle Excision TechniqueDocument3 pagesCarbuncle Excision TechniquetseeckunNo ratings yet

- Kuliah BasaliomaDocument49 pagesKuliah BasaliomaRobert HarrisNo ratings yet

- Basal Cell CarcinomaDocument6 pagesBasal Cell CarcinomaSharvienraaj VelukumaranNo ratings yet

- SCC BCCDocument13 pagesSCC BCCSippy Iqbal MemonNo ratings yet

- Buccal Mucosa CancerDocument9 pagesBuccal Mucosa Cancermuhammad_ariefNo ratings yet

- CASE NUMBER 1 TTDocument5 pagesCASE NUMBER 1 TTSoundhariya GNo ratings yet

- CASE NUMBER 1 Tt-CompressedDocument5 pagesCASE NUMBER 1 Tt-CompressedSoundhariya GNo ratings yet

- Hasil Penelitian KSSDocument3 pagesHasil Penelitian KSSMarlboro LightsNo ratings yet

- 33 FullDocument7 pages33 FullDr SS ki VinesNo ratings yet

- Procedimientos Vulva PDFDocument14 pagesProcedimientos Vulva PDFTheodoraAlinaNo ratings yet

- IndianJOphthalmol646415-1313542 002153Document7 pagesIndianJOphthalmol646415-1313542 002153Renie IndrianiNo ratings yet

- 2.12.1 Benign and Malignant Lesions of The Head and NeckDocument13 pages2.12.1 Benign and Malignant Lesions of The Head and NeckZayan SyedNo ratings yet

- Orbit Eyelids and Lacrimal SystemDocument6 pagesOrbit Eyelids and Lacrimal SystemZaher Al ObeydNo ratings yet

- Reti No Blast OmaDocument15 pagesReti No Blast OmaditaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Incisions Balancing Surgical and Cosmetic Outcomes in Head and Neck OncosurgeryDocument4 pagesSurgical Incisions Balancing Surgical and Cosmetic Outcomes in Head and Neck OncosurgeryDwarika Prasad BajgaiNo ratings yet

- eCTD Guidance v4 0-20160422-FinalDocument62 pageseCTD Guidance v4 0-20160422-FinalvinayNo ratings yet

- Potato and Banana Chips-5481588926613949Document40 pagesPotato and Banana Chips-5481588926613949satubhosale100% (1)

- Nihon Kohden BSM-2300 - Service ManualDocument207 pagesNihon Kohden BSM-2300 - Service ManualĐức Cường100% (2)

- A Novel Use of Coblation in The Treatment of Subglottic StenosisDocument14 pagesA Novel Use of Coblation in The Treatment of Subglottic StenosisFabian Camelo OtorrinoNo ratings yet

- Demografi Mind MapDocument3 pagesDemografi Mind MapAnis Elina ZulkipliNo ratings yet

- 2014 BGCSE Biology Paper 4Document8 pages2014 BGCSE Biology Paper 4cleohambiraNo ratings yet

- CDIL TransistorsDocument4 pagesCDIL Transistorsjjtrivedi8717No ratings yet

- Honeywell DPR 2300 and 3000Document338 pagesHoneywell DPR 2300 and 3000kmpoulosNo ratings yet

- Ethyl BenzeneDocument10 pagesEthyl Benzenenmmpnmmpnmmp80% (5)

- Scientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDocument6 pagesScientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDaniel VasquezNo ratings yet

- Soda AshDocument2 pagesSoda AshswNo ratings yet

- MenevitDocument6 pagesMenevitjalutukNo ratings yet

- The AlchemistDocument57 pagesThe Alchemistok100% (1)

- 2000 Series Design TablesDocument36 pages2000 Series Design Tablesjunhe898No ratings yet

- Is 9259 1979 PDFDocument15 pagesIs 9259 1979 PDFsagarNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument4 pagesAssignmentoolyrocksNo ratings yet

- SR Elite, Aiims S60 & Neet MPL Aits Grand Test - 15 Paper Key (23-04-2023)Document12 pagesSR Elite, Aiims S60 & Neet MPL Aits Grand Test - 15 Paper Key (23-04-2023)vulurakashsharma2005No ratings yet

- Risk Assessment- SAMPLEDocument6 pagesRisk Assessment- SAMPLErica.nynecorporationNo ratings yet

- Soal UAS 2023 KELAS 9Document5 pagesSoal UAS 2023 KELAS 9MASDALYLA TINENDUNGNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Culinary ArtsDocument10 pagesIntroduction To Culinary ArtsNico Urieta De AdeNo ratings yet

- Component Replacement - 010Document11 pagesComponent Replacement - 010artemio hernandez gallegosNo ratings yet

- Information For Replacement of The FR-S500 (S500E) Series by The FR-D700 SeriesDocument19 pagesInformation For Replacement of The FR-S500 (S500E) Series by The FR-D700 SeriesСергей АльохінNo ratings yet

- BLDC Motor Test SystemsDocument12 pagesBLDC Motor Test SystemsKaung Khar100% (1)

- Ifedc 2022 Rock TypingDocument17 pagesIfedc 2022 Rock TypingpetrolognewsNo ratings yet