Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Winter 2013 Journal of Politics & International Affairs

Winter 2013 Journal of Politics & International Affairs

Uploaded by

Cameron DeHartCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Winter 2013 Journal of Politics & International Affairs

Winter 2013 Journal of Politics & International Affairs

Uploaded by

Cameron DeHartCopyright:

Available Formats

e Journal of Politics and

International Anairs

Volume V, Issue I

Winter 2013

e Journal of Politics

and International Aairs

Volume V, Issue I

Winter 2013

e Ohio State University

Cameron DeHart

Editor-in-Chief

Charles Trefney

Logistics

Professor Paul Beck

Advisor

Joseph Guenther

Managing Editor

Wayne DeYoung

Advisor

JPIA Editorial Sta:

Phillip Allen

Sarah Arnold

Je Carroll

Taylor Humphrey

Chelsea Hagan

Nickole Iula

Todd Ives

Maegan Miller

Ben Presson

Alumni Advisor

Seth Radley

Design

Holly Yanai

Contents

Sparta and Plataea: Target Selection in the Age of

Religiously Motivated Terror 09

David Agranovich

Caring for the Constitution: Madison and Jeersons

Opposition to the Nation Bank of the United States 21

Yana Mereminsky

Preventing the Loss of Life in Syria 63

Alex Polivka

Black Voting Behavior and Californias Proposition 8 79

Christopher Rupp

Prosecute or Pardon: What Impunity in El Salvador Says

About Transnational Justice Everywhere 95

Adam Schaer

Middlebury College

e New Geopolitics of the Artic 111

Alexander ompson - Associate Professor

Volume V Issue I Winter 2013 Online Edition

Journal of Politics and

JPIA

International Aairs

e Journal of Politics and International Aairs at e Ohio State University is published biannually through the

Ohio State Political Science Department at 2140 Derby Hall, 154 North Oval Mall, Columbus Ohio 43210.

e JPIA was founded in the autumn of 2006 and reestablished in Winter 2011. For further information, or to

submit questions or comments, please contact us at journalupso@gmail.com.

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in

any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written

permission of the Editor-in-Chief of the JPIA. e JPIA is copyrighted by the Ohio State Political Science

Department. e content of all papers is copyrighted by their respective authors.

All assertions of fact and statements of opinion are solely those of the authors. ey do not necessarily represent

or reect the views of the JPIA Editorial Board, the Faculty Advisers, e Ohio State University, nor its faculty

and administration.

COPYRIGHT 2013 THE OHIO STATE JOURNAL OF POLITICS AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Welcome,

It is my pleasure to present the Winter 2013 edition of e Journal of Politics & International Aairs.

is issue features several exciting and relevant papers that speak to the strength of the undergraduates

at e Ohio State University. Our editorial team has been working diligently over the past several

months to put this project together, and hopefully the end result is both informative and enjoyable.

Loyal readers of JPIA will notice several changes to the layout of the winter issue. In spring 2012, we

bid adieu to several of our graduating editors and welcomed several fresh faced underclassmen to ll

their positions. Over the summer and fall, the upperclassmen have been mentoring the new editors

and this issue has been a truly collaborative eort by the old and new guard.

Our editorial team identied several areas for improvement after our spring issue was released in June.

In this issue, we worked to improve continuity with regards to formatting, citation style, and other

stylistic aspects. Readers will also notice new biographies for our editorial sta.

Sadly, this issue will be my last as editor-in-chief. As I prepare for graduation in the spring and gradu-

ate school in the fall, I am leaving this project in the hands of my capable successor, Chelsea Hagan,

and the new editorial sta. I hope to stay involved in an advisory role, and I look forward to seeing

how the Journal evolves after my departure.

is issue would not have been possible without the support the Political Science department. I

would like to thank you to Dr. Richard Herrmann for his support and condence in our team, Alicia

Anzivine and Wayne DeYoung for their assistance at every stage of this project, Dr. Paul Beck for

his guidance and administrative support, and Ben Presson for his continuing insights as our alumni

adviser.

Lastly, I would like to thank all those who read the Journal. Your feedback and supports keeps this

project going. ank you.

Cameron DeHart

Editor-in-Chief

Editorial Foreword

Cameron Dehart

Editor-in-Chief

Sparta and Plataea: Target Selection in the

Age of Religiously Motivated Terror

David Agranovich

While terrorism has, since its inception, resulted in civilian casualties, the deliberate targeting of civilians

seems to be a new trend. is essay contrast the targeting methodologies of major terrorist organizations as they

evolve over time in order to evaluate the hypothesis that the increase in civilian targeting is the result of the

growth of an international competitive funding market and the ability of terrorist groups to use new ideologies

to rationalize making civilians primary targets. is analysis focused on the actions and ideology of the IRA

during the Troubles to establish a baseline for terrorist targeting in which the primary targets were government

and military, and in which civilian casualties were strongly discouraged. We then contrasted the targeting

methodology used by al-Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula to identify chief dierences that may have contributed

to forming a civilian-centric targeting model.

9

T

he assassination of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich at the hands of a terrorists bomb

would have been an unmemorable data point in a long history of political violence if it

were not for the incredible caution of his killer. In a country already bathed in blood from

rising civil unrest and widespread famine, it would be an act of mercy, rather than an act of murder,

that would capture the minds of historians for more than a century. e assassin, a member of the

terrorist Socialist Revolutionary Combat Organization named Ivan Kalyayev, was originally slated to

carry out the attack two days earlier but stayed his hand when he saw his victim accompanied by

his wife and young nephews. Loath to take innocent lives, Kalyayev melted back into the crowd, and

nally completed his mission two days later. He hoped to be remembered for inspiring the socialist

revolution of Russia, but instead became the paradoxical picture of a moralistic terrorist.

Nearly a century later, the concerted attacks on the Twin Towers and Pentagon in Septem-

ber 2001 took many Americans by surprise, and shook Americas sense of security to the core. ough

the rst attack on the World Trade Center in 1993 was not so far in the past, an attack of this mag-

nitude by a foreign entity on American soil had not happened in sixty years. As the towers crashed to

the ground, a nation mourned the deaths of over 3000 citizens, many of whom were civilians. As res

still burned at the Pentagon, the country was still coming to grips with their attacker a group almost

entirely unknown to the average American and the possible justication for targeting thousands of

noncombatants. e attacks of 9/11 only highlighted an apparently new norm in terrorist targeting

practices: one in which civilians are legitimate, and often preferred, targets in terrorist attacks.

ese anecdotes help illustrate emerging trends in terrorist target selection and behavior. Terrorism

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

10

Agranovich Sparta and Plataea

11

in the early 19

th

and 20

th

centuries was largely bound by national borders, and often operated against

a single identiable entity with practical policy goals. is analysis is derived from the actions of

major terrorist groups in this period. e Irish Republican Army, though notorious for its wave of

violence against British state agents (police, army) was dened as a group composed of Catholic Irish

separatists allied against the British government, with the stated aim of securing Irish independence

through concerted attacks against symbols of the British state (Coogan 2000, 547) (Irish Republican

Army 2009). e Baader-Meinho gang in Eastern Germany also tended to focus on targets clearly

associated with the State. Even in the era of anti-Tsarist terrorist organizations, attacks focused on

State targets, with every eort made to avoid unnecessary civilian casualties (*See Kalyayev) (Merari

1993, 227-228).

Somehow, the calculus of target selection seems to have changed to emphasize visibility of

the attack over any other consideration a calculus that now places civilians directly in the crosshairs

of terrorist planners. In this essay I will analyze the factors that have contributed to this change by

contrasting al-Qaeda and the IRA in order to evaluate the hypothesis that terrorist targeting is a result

of a combination of the rationalization of civilians as agents of antagonistic powers and the creation

of a competitive funding marketplace.

Literarature Review

e academic study of terrorist targeting methodology has overwhelmingly focused on

Islamist terror groups and the religious reasoning behind target selection. However, Fathali M.

Moghaddams essay e Staircase to Terrorism explores the psychological steps that terrorists take to

select, plan, and execute an attack. He denes terrorism as politically motivated violence, perpetrated

by individuals, groups, or state-sponsored agents, intended to instill feelings of terror and helplessness

in a population in order to inuence decision making and to change behavior (Moghaddam 2005).

His denition highlights the importance of considering terrorism from an objective standpoint in

order to impartially analyze the factors contributing to changes in terrorist behavior (such as the

introduction of religious or philosophical rationalization or belief ). Moghaddam then presents a

six-part stairway a set of six steps that would-be terrorists ascend until ultimately rationalizing

violence and destructive acts. He postulates that every individual begins on the ground oor at

which individuals perceive injustice and fairness and conceive of their own place in their environment

(Moghaddam 2005). He points out that the individuals who rise above the ground oor tend not

to conform to the notions of terrorists as unemployed, uneducated foot soldiers commonly held by

Western media, but rather, in the case of the IRA, there is a stratum of intelligent, astute, and expe-

rienced terrorists who provide the backbone of the organization[that] does not support the view

that they are mindless hooligans drawn from the unemployed and unemployable (Coogan 2000,

485)(Moghaddam 2005). He goes on to point out that more recent organizations, like al-Qaeda and

Bin Laden himself, come from educated and often wealthy backgrounds (Wright 2006). Moghaddam

addresses the concept of moral engagement as a driving force behind the rationalization of violence

against civilians and government targets. He explains that terrorist groups will try to portray their

targets as morally disengaged, while the group itself develops a secondary, parallel morality that

justies the use of violence (Moghaddam 2005). Finally, he identies the fth oor as the condition-

ing necessary to justify the deaths of civilians by sidestepping inhibitory mechanisms (Moghaddam

2005). He states that two important psychological processes are necessary to facilitate the murder of

civilians: the rst involves social categorization of civilians as part of the out-group, and the second

involves psychological distance through exaggerating dierences between the in-group and the out-

group (Moghaddam 2005). Moghaddams nal oor will be an important part of my argument that

the targeting of civilians stems from the rationalization of their complicity in the actions of the enemy.

Ariel Merari, in his essay Terrorism as a Strategy of Insurgency, explores the application of the

term terrorism as a political tool. He argues that terrorism is too often applied punitively as violence

we nd objectionable (Merari 1993, 213-214). As such, we must be cautious to identify terrorist

groups not only objectively from the standpoint of emotional response, but also from an orientalist

perspective, as Merari notes, Western academic denitions of terrorism often dier signicantly from

those found in Iran, Syria, and many African nations (Merari 1993, 215). Merari argues that terror-

ism can only be perpetrated by citizens, rather than by states, and that the targets of terrorism can

be either states or civilians (Merari 1993, 218). However, he delineates between state-targeted and

civilian-targeted terrorism. According to Merari, terrorists that target states are guerillas, insurgents,

or revolutionaries, whereas those that target civilians are vigilantes and ethnic terrorists (Merari

1993, 218).

While his dichotomy questionably assigns perceived moral value to certain types of terror-

ism, he continues by discussing the practical morality of terrorism as portrayed by Ivan Kalyayev, a

bomber during the anti-Tsarist period in Russia. Kalyayev, who avoided civilian casualties to the point

of abandoning his rst attempted attack, was, in Meraris eyes one of the few terrorists who pass the

litmus test for moral violence. is litmus test, described by Walzer (as quoted by Merari) as a scale

of assasinability, with government ocials being highly assasinable, and civilians being illegitimate

targets (Merari 1993, 228). However, it is Meraris conviction that moral judgments cannot be passed

on terrorist activity because morality is a code of behavior that prevails in a certain society at a certain

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume IV Issue III Fall 2012

12

Agranovich Sparta and Plataea

13

time (Merari 1993, 230) that informs this papers approach to civilian targets not as morally ille-

gitimate targets, but rather as targets systematically rationalized from the moral standpoint of terrorist

organizations themselves.

e Irish Republican Army

Ireland has been the home to a struggle for independence since the 1500s, when King

Henry VIII assumed the title of King of Ireland. His heavy-handed conquest of the island was fol-

lowed in the late 1700s by a unication treaty admittedly bought through bribery and the awarding

of peerages to important representatives (Ward 1994). Ireland then endured the hardship of the Irish

Potato Famine, caused in part by its sudden unication with the UK, which encouraged its agricul-

tural growth in lieu of industrial power (Mokyr 1983). Finally, in response to the frustration felt by

the Irish, the Home Rule Bill was introduced into parliament. However, the advent of WWI caused

its suspension, and provoked a split among Irish nationalists between those that supported the war

eort and those that opposed it. However, the Easter Day Uprising in 1916, and subsequent execu-

tion of fteen of its leaders, turned the tide of public opinion in favor of the separatists, and led to the

beginning of the 1919 civil war.

e Irish Republican Army traces its roots back to the Dil of 1919 and the Irish War of Indepen-

dence from 1919-1921. At the beginning of the conict, the Dil approved the IRA as the ocial

armed forces of the Irish Republic, vesting them with the legitimacy necessary to begin their guerilla

campaign against the British. After the end of the war in 1921, IRA members opposed to the Anglo-

Irish Treaty set about ghting the Irish Civil War against the members of the IRA and Sinn Fein

that had signed the treaty. is group, too, held that their legitimacy stemmed from the 1916 Dil

proclamation. In 1969 the group split again, into the Provisional IRA (pIRA) and the Ocial IRA

(oIRA), the latter of which ceased operation in 1972 after the troubles, and the former of which split

again after the 1997 ceasere (and subsequent 2005 cessation of hostilities) into the Real IRA and the

political wing of the pIRA, the Provisional Sinn Fein. roughout its history, from its founding and

through various splits, the IRA has maintained its legitimacy through the Dils 1916 proclamation

naming it the ocial armed forces of the Republic of Ireland (Coogan 2000), and was ultimately

responsible for over 1700 deaths throughout the conict (Sutton 2006). I will focus on the IRA be-

ginning during the time of the Troubles and continuing through the dissolution of the PIRA.

IRA Methodology

IRA attacks usually took the form of shootings/assassinations of police or military mem-

bers operating in the IRAs home territory or bombings (usually by car bomb) of banks, government

buildings, and government events. While the death toll during the troubles reached over 1700, of

which 621 were civilians (during the most violent time in IRA history). As such, the IRA could be

considered as an organization that avoided the killing of civilians when possible (as dened by their

own logic) and focused attacks on visible members of the state apparatus namely, those high on

Walzers assasinability scale.

IRA tactics emphasized the minimization of collateral damage by openly notifying police

or residents of a target building of the imminent bombing threat, with the hope that the building

would be cleared in time. Oftentimes, this approach was successful, however, during the Troubles

IRA cells, which were by denition very insulated from each other for security purposes (Coogan

2000), often carried out attacks that, either through insucient warning time or a unmanageably

large number of simultaneous attacks, led to civilian casualties and injuries. One such event was the

Bloody Friday bombings on July 21, 1972, in which killed nine people (seven civilians and two

soldiers) and injured 130, most seriously, of which almost all were civilians (McKenna n.d.). e

attack included 19 bombings over a span of 80 minutes in Belfast in major transit centers and busy

street corners (McKenna n.d.). While the IRA provided, in some cases, substantial (30-70 minute)

warnings, the density of the attacks led to victims being evacuated to other bomb sites and two hoax

warnings signicantly delayed emergency response time (McKenna n.d.).

Rationalization of civilian collateral deaths

IRA response to the deaths of Bloody Friday and other civilian casualties during its bomb-

ing campaign was one of dissociation from responsibility for the event, and even in admitting mis-

takes, the group focused on the tactical error of allowing the British to win a public opinion battle

rather than their planning error in causing civilian casualties. In the Green Book, the IRA volunteers

handbook, civilian casualties were explained as regardless of [whether we overestimated the Britishs

ability to respond to our warnings], we made the mistake and the enemy exploited it [by using as

public relations material against the IRA (Coogan 2000, 552). However, the IRA views the exploi-

tation of its mistake by the enemy as a logical response to their attacks, and urges its members to

exploit [their] mistakes by propagating the facts. So it was with their murderous mistakes of the Falls

Road curfew, Bloody Sunday, and internment (Coogan 2000, 552).

Changes in targeting methodology during the ultra-violent Troubles were also explained

away by placing blame on the enemy for forcing the IRA to resort to more brutal tactics. e Green

Book states tactics are dictated by existing conditions and that those conditions were changed not

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

14

Agranovich Sparta and Plataea

15

by the actions of the IRA, but by actions of the British, such as the Falls curfew after which all

Brits to a people were acceptable targets. e existing conditions had changed (Coogan 2000, 552).

Coogan also points out how the IRA rationalized the execution of its own members or civilians by

associating them with arms of the state. He notes three anecdotes of civilian executions: the murder of

businessman Jeery Agate, conducted because the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland was trying

to drum up investment in the country, the murder of Sir Norman Stronge and his son in response to

sectarian killings of Catholics, and the murder of the Carrols to expound on the IRA opposition to

the process of turning volunteers to the Brits (Coogan 2000, 553). In each case, the organization

was capable of rationalizing civilian casualties by arguing each target was helping to service the war

machine of their enemies (Coogan 2000, 553).

Al-Qaeda

Al-Qaedas origins also begin in a conict for sovereignty. e invasion of Afghanistan by

Soviet troops caused a massive inux of ghters from neighboring regions bent on joining the various

coalitions ghting the Soviet army. Dubbed mujahedeen, they hailed from a myriad of countries but

ultimately shared two things: Muslim faith and a conviction that the expulsion of the Soviets was

both a tactical and ideological imperative. Osama bin Laden, a wealthy son of a Saudi (previously

Yemeni) construction mogul, began his armed career as a nancier of the mujahedeen, providing a

series of guesthouses across the Afghan border in Pakistan to assist mujahedeen receiving training and

preparing to head to the front lines (Wright 2006). As the war progressed, bin Laden, hungry for

action, went to the front lines, where he was notably a terrible soldier and suered from a myriad of

health problems that severely handicapped his ability to ght (Wright 2006). However, it was here

that he began gathering a group of elite Egyptian mujahedeen led by Ayman al-Zawahiri. From this

group he culled the most elite and dedicated of ghters, from which the roots of al-Qaeda were born

(Wright 2006). Al-Qaeda initially focused on consolidating its power in Afghanistan by eliminating

the leader of the Northern Alliance, Ahmed Shah Massoud and allying itself with the Taliban.

While al-Qaedas initial attacks focused on government buildings and military resources,

it displayed absolutely no concern about the deaths of civilians. e bombings of the US embassies

in Kenya and Tanzania were timed for the busiest part of the workday, and the truck bombs used

were of such power that they nearly obliterated the entire buildings, including the publicly accessible

facades and killing over 270 people and injuring over 5000 (Wright 2006). ese targets were chosen

not only to make the political statement that American presence overseas was unacceptable, but also

to present al-Qaeda to the world in spectacular fashion (Wright 2006).

Al-Qaeda and Civilian Targets

Al-Qaeda has since its inception made no eort to avoid civilian casualties, often using

large death counts as vehicles for enhancing its visibility. While several arguments rationalizing the

killing of civilians especially the deaths of Muslims exist, the answer can in part be found in the

ideology that gave birth to the organization. e heavy inuence of Egyptians in the initial al-Qaeda

organization is no coincidence. Ayman al-Zawahiri himself spent time in prison with Syyid Qutb,

the Egyptian revolutionary who developed the idea of takr, the process of declaring a Muslim an

apostate, which legitimizes his death. It was through this theological trick that al-Qaeda was able to

rationalize the deaths of hundreds of Muslim civilians in the embassy bombings and the deaths of any

Muslims during the 9/11 attacks. However, the issue of killing civilians in general is more compli-

cated.

e al-Qaeda approach seems to mirror that of the IRA, just with more readiness to declare

civilians as servicing the war machine of the enemy. In his 1996 fatwa, bin Laden argues that all

those who live without Sharia are apostates, and that to use man made law instead of the Sharia and

to support the indels [here, the United States] against the Muslims is one of the ten voiders that

would strip a person from his Islamic status (Bin Laden 1996). With this act, bin Laden not only

validates the killing of Muslims by stripping them of their status as Muslims but also indicates that

complicity with the enemy (much like the IRAs belief that noncombatants were aiding the enemy

by not taking arms against it) was enough to justify being a target. Al-Qaedas call to target civilians

of any religion appears in the 1998 World Islamic Front fatwa, which stated to kill the Americans

and their allies civilians and military is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any

country in which it is possible to do it (World Islamic Front 1998).

Similarities in Rationalization of Civilian Casualties

An analysis of the methods by which the IRA and Al-Qaeda rationalize civilian casualties as

a result of their attacks does turn up some similarities. Much like in cases of domestic violence, both

groups disassociate themselves from the violence, arguing that the death of civilians was somehow

the fault of the enemy themselves. e IRA takes special care to frame such casualties as the intended

action by the enemy, arguing that the unsuccessful evacuation of victims was a ploy by the British

forces to attack the image of the IRA (Coogan 2000). To both groups, the rationalization of civilian

casualties begins with accepting civilians as extensions of the state machine and arguing their actions

somehow contribute to the perceived injustice motivating the terrorist. In this way, these groups can

morph Walzers assassinability index to allow for civilian targets.

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

16 17

Agranovich Sparta and Plataea

Dierences in Rationalization of Civilian Casualties

However, during the bloodiest period of IRA history, the organization was responsible

for only 621 civilian deaths (Sutton 2006). In contrast, al-Qaedas most high-prole attacks the

embassy bombings, the London transit bombings, and the 9/11 bombings claimed the lives of 3275

civilians (BBC 2005)(PBS Online Newshour n.d.). e chief dierence between these two organi-

zations is the deliberate targeting of civilians undertaken by al-Qaeda, as opposed to the attempts

frequently made by the IRA to avoid unnecessary civilian casualties. e language of the 1998 fatwa

is illuminating because it seeks to justify the murder of American civilians precisely because they

are Americans and therefore surrogates of the oppressive state regime the organization is targeting

(World Islamic Front 1998). Here we see the dening deviation between the IRA and al-Qaedas

methodologies: while the IRA saw civilian casualties as a hindrance to accomplishing their goals (a

tool to be used against them), al-Qaeda sees civilian casualties as a visibility maximizer, and actively

sought attacks that would inspire the greatest amount of fear in the general population.

For al-Qaeda, this legitimacy sprung from a perverted understanding of Islam, one in

which an individual without traditional religious training and outside of the ulama could make pro-

nouncements of Islamic law. It was by this process the incorporation of Qutbs teachings on takr

and kar and the Wahhabi concept of individual interpretation of he Quran that Moghaddams

nal step in the staircase was overcome, and an all-out assault on civilians was morally and psychologi-

cally excusable.

e Competitive Funding Marketplace

A phenomenon of the growth of transnational terrorism is the need for terrorist groups to

compete among themselves for the money necessary to remain in the public eye. Katie Benner quotes

an anonymous al-Qaeda operative saying there are two things a brother must always have for jihad,

the self and money (Benner 2011). Islamic terrorism especially feeds o of a system of clandestine

nancial sources. Islamic banking, with its insulation from the international banking system and

informal regulation, allows for easy transmission of cash to militant groups. Wealthy charities active

in the Islamic world have been implicated in funding numerous terrorist organizations (National

Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States 2004). However, the creation of a funding

source network (with nite resources) means that organizations must compete for those resources.

e meticulous nature in which bin Laden himself worried over the branding of al-Qaeda

in his later years lends credence to the importance of having a competitive and visible brand. Wor-

ried his organization was losing funding and relate-ability, he asked tells his deputies the name of an

entity carries its message and represents it. Al-Qaeda describes a military base with ghters without

a reference to our broader mission to unify the nation and charges them to nd a name that would

not be shortened to a word that does not represent us (Bin Laden, SOCOM-2012-0000009-HT

2012).

e need for a strong brand and visible image is a dening reason for the rationalization of

the killing of civilians. By targeting civilians, al-Qaeda managed to shoot to prominence on the world

stage. Its attacks on US embassies sparked immediate attention from the FBI (Wright 2006) and its

destruction of the World Trade Center towers and attack on the Pentagon established it as a global

franchise. ough al-Qaeda found it immensely harder to fundraise after 9/11 (due to vigilance on

the part of the Saudis and the American and British intelligence services), there is strong evidence that

their fundraising abilities were heightened after their initial attacks (Wright 2006) (Roth, Greenburg

and Wille 2004). e intense media attention that spectacular attacks with high civilian casualties

garner is also an integral part to sustained operation as an organization (Richards 2011). ere ap-

pears to be a clear need for visibility in order for terrorist organizations to remain relevant a type of

visibility that is only enhanced by massive attacks on civilian soft targets (Richards 2011).

Concluding remarks

e growth of terrorist attacks targeting civilians can be clearly shown to have two major

sources: the need for funding in a competitive market and the ability for terrorist organizations to

both rationalize, and later prioritize, civilian attacks. e growth of a viable transnational terrorist

funding network created a competitive marketplace in which organizations like al-Qaeda were forced

to act like businesses competing for venture capitalist funding by enhancing the visibility of their

brand and our-competing their competitors. In this sector, the language of the corporate world ap-

plies mergers like the one between Egyptian Islamic Jihad and bin Ladens edgling al-Qaeda were

calculated to form organizations that could appeal to broader funding bases and audiences (Wright

2006), while garnering the funding necessary for large simultaneous attacks.

While terrorism has, since its inception, resulted in civilian casualties, the deliberate target-

ing of civilians seems to be a new trend. e advent of ideological arguments for associating civilians

with the state apparatus and for widening the gap between in- and out-group individuals, such as

Qutbs philosophy of takr and bin Ladens interpretation of qh, has created a system in which civil-

ians are far easier to associate with legitimate targets, and has blurred the lines delineating the steps on

the stairway to terrorist actions.

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

18

Agranovich Sparta and Plataea

19

Works Cited

Associated Press. Foreign attacks on U.S. soil rare in nations history. September 12, 2001. http://www.

deseretnews.com/article/863516/Foreign-attacks-on-US-soil-rare-in-nations-history.html (accessed

April 20, 2012).

BBC. List of the bomb blast victims. BBC World News. July 20, 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/

uk_news/4668245.stm (accessed May 5, 2012).

Benner, Katie. Bin Ladens gone, but what about al Qaedas nances? CNN. May 2, 2011. http://

nance.fortune.cnn.com/2011/05/02/bin-ladens-gone-but-what-about-al-qaedas-nances/ (accessed

May 8, 2012).

Bin Laden, Osama. Declaration of War against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy

Places. PBS. August 1996. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/terrorism/international/fatwa_1996.html

(accessed April 15, 2012).

. SOCOM-2012-0000009-HT. Combatting Terrorism Center. May 3, 2012. http://www.ctc.

usma.edu/posts/letters-from-abbottabad-bin-ladin-sidelined (accessed May 7, 2012).

Coogan, Tim Pat. e IRA. London: Harper Collins, 2000.

Irish Republican Army. Irish Republican Army Green Book. May 29, 2009. http://www.scribd.com/

doc/15914572/IRA-Green-Book-Volumes-1-and-2 (accessed May 3, 2012).

McKenna, Fionnuala. Bloody Friday (21 July 1972) - Northern Ireland Oce News-sheet. http://cain.

ulst.ac.uk/events/bfriday/nio/nio72.htm (accessed May 5, 2012).

Merari, Ariel. Terrorism as a Strategy for Insurgency. Terrorism and Political Violence (Frank Cass)

5, no. 4 (1993): 213-251.

MI5. A-Qaidas History. https://www.mi5.gov.uk/output/al-qaidas-history.html (accessed May 6,

2012).

Moghaddam, Fathali M. e Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration. American Psy-

chologist (e American Psychological Association) 6, no. 2 (March 2005): 161-169.

Mokyr, Joel. Why Ireland Starved: A Quantitative and Analytical History of the Irish Economy, 1800

1850. Oxford: Taylor and Francis, 1983.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. e 9/11 Commission Report.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004.

PBS Online Newshour. African Embassy Bombings: An Online Newshour Special Report. PBS

Online Newshour. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/africa/embassy_bombing/map.html (accessed

May 7, 2012).

Richards, Anthony. Terrorism and the Olympics: Major Event Security and Lessons for the Future. New

York: Taylor & Francis US, 2011.

Roth, John, Douglas Greenburg, and Serena Wille. National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon

the United States Monograph on Terrorist Financing. 9/11 Commission Report. July 26, 2004. http://

www.9-11commission.gov/sta_statements/911_TerrFin_Monograph.pdf (accessed April 3, 2012).

Sutton, Malcolm. An Index of Deaths from the Conict in Ireland. March 6, 2006. http://cain.ulst.

ac.uk/sutton/tables/Organisation_Responsible.html (accessed May 5, 2012).

Ward, Alan J. e Irish Constitutional Tradition: Responsible Government and Modern Ireland, 1782

1992. Washington, DC: Catholic University Press, 1994.

World Islamic Front. Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders. PBS. February 23, 1998. http://www.pbs.

org/newshour/terrorism/international/fatwa_1998.html (accessed May 3, 2012).

Wright, Lawrence. e Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. New York: Knopf, 2006.

Caring for the Constitution: Madison and Jeersons

Opposition to the National Bank of the United States

Yana Mereminsky

In the present-day United States, the Constitution is of utmost legal authority. is conception can be traced to

historical events in which constitutional doctrine decided legal questions. e rst event that set a tradition of

constitutional clout was the 1790s National Bank Debate. Alexander Hamilton proposed a National Bank bill to

strengthen the economy and alleviate the Revolutionary war debt. James Madison and omas Jeerson opposed

the bill and appealed to George Washington to impose his Veto against it. Ultimately, Washington signed the bill.

Modern historical thought asserts that Madison and Jeersons greatest criticism of the Bank was its unconstitutional-

ity. is view may be incorrect. e purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that Madison and Jeersons true op-

position lay with political-economic concerns and their constitutional argument was a ploy that they thought would

convince Washington. e studys research method included investigating primary and secondary sources, economic

and legal theories that were inuential in the late eighteenth century, and Madison and Jeersons motivations.

Results indicate evidence that conrms the hypothesis, such as Madison and Jeersons written correspondence, prior

ideologies, and perception of Washingtons priorities. erefore, results show that Madison and Jeersons genuine op-

position to the Bank in the political-economic realm. e implications of the research are important in considering

the symbolism of the Debate. If Madison and Jeerson were insincere in voicing a constitutional opposition against

Hamiltons bill, the American tradition of granting utmost legal authority to the Constitution is based, at least

partly, on a disingenuous source.

21

P

resident Barack Obamas health care reform bill has been both the most distinguishing foot-

print left by his administration and the most disputed. As debates over the bill surged

throughout the nation, many opponents turned to a question of constitutionality to defeat

the plan. ese critics of the bill used the Commerce Clause as their point of attack, while President

Obamas supporters armed the bills absolute compatibility with the clause and the Constitution.

Federal courts were divided over the issue, with four of the major appeals court decisions shedding

little light on the overall judicial position on the law.

1

When the bill nally reached the Supreme

Court, much of the nation and probably all of its politicians tuned in to hear what the Justices had

to say regarding the laws constitutionality. In the end, Chief Justice John Robertss opinion armed

the constitutionality of the bill.

As the battle raged, strikingly few credible government ocials or national leaders would

have even thought to question the relevance of constitutionality in regards to health care reform. In

this context, the debate over health care reform revolved around whether the bill was constitutional

or unconstitutional, not abouAAt whether constitutionality is important. If the Supreme Court had

stricken down the reform as unconstitutional, no one would have dared to say that it should have

been implemented anyway. e treatment of the Constitution as a document of unmatched legal

importance in American politics is a sentiment shared by the overwhelming majority and one that has

been around for hundreds of years. But when was this sentiment born? What created the unshake-

able foundation for constitutional superiority that lives in American politics today?

e rst truly monumental question of legislative constitutionality presented itself in the

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

22

Mereminsky Caring for the Constitution

23

1791 National Bank debate. e National Bank, as envisioned by Alexander Hamilton, Secretary

of the Treasury at the time, was proposed to the First Congress in 1790. His Second Report on Public

Credit, which contained the Bank proposal, was one of three important works that unveiled Hamil-

tons entire economic policy, along with the 1789 First Report on Public Credit and late 1791 Report on

Manufactures.

2

e First Report had argued that a funded debt (in this context, the American post-

Revolutionary war debt) could be transformed into capital, and the Second Report recommended

that this transformation be performed through a Bank.

3

Ultimately, Hamiltons main objective in

funding the debt through the incorporation of the Bank was to stabilize the new national govern-

ment and establish its credit. In other words, he aimed to ease the investment of private capital.

Hamiltons more specic hopes revolved around ambitious entrepreneurs and their ability to give the

American economy a signicant push. He predicted that the Bank would attract both foreign and

domestic capital into the possession of these entrepreneurs, and the entrepreneurs would, in turn,

invest the capital into the nations economic growth. is sort of wealth concentration was impera-

tive, Hamilton reasoned, in an underdeveloped frontier society like the US where manufactures were

few, capital frequently diused, and thus currency depleted. Helping to eliminate these negative traits

of the American economy, concentration and mobilization of capital would excite the industry and

productivity of the American people. Likewise, it would cure a chronically unfavorable balance of

trade by encouraging export production.

4

Finally, it would act as both a source of emergency loans

and a depository of funds.

5

Hamiltons constitutional justication for the Bank derived from Article 1, Section 8,

which gave Congress the power to borrow Money on the credit of the United States. He reasoned

that the Bank itself would supply these loans. Although no explicit power allowed Congress to es-

tablish such a Bank, Hamilton looked to the Necessary and Proper Clause of Article 1, Section 8 for

constitutional justication: Congress would have the right to make all Laws which shall be necessary

and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, which included the aforementioned

power to borrow money.

6

However, the Bank proposal met erce opposition from Secretary of State omas Jeer-

son and Virginia Congressman James Madison. eir criticisms revolved around two major points

of contention: ey viewed the Bank as economically corrupt and unsound, and they viewed it as

unconstitutional in the context of the Necessary and Proper Clause.

Madison found abundant economic aws with the Bank bill. He asserted two particular

disadvantages in his 1791 speeches to Congress: e Bank would abolish precious metals as the basis

for currency by substituting another nancial medium for them, and it would expose the American

people to the risk of a run on the Bank. Moreover, what troubled Madison even more was that these

evils would be unleashed onto the public in the form of an eleven-year Bank charter, which was much

too lengthy for his liking.

7

Yet just like Jeerson, Madison aimed the majority of his publically voiced

opposition to the Bank at its unconstitutionality. He claimed that constitutionally granted Congres-

sional power to borrow did not imply the power to charter a bank to make loans.

8

For Jeerson, the Bank eectively represented the evils that he attributed to all banks of

note issue (rather than gold issue). Instead of helping people succeed, banks preyed on people, put

them into debt, and supported luxury and extravagance.

9

In short, banks did not create capital as

bank proponents claimed, rather they diverted it from virtuous agricultural pursuits

10

Ultimately

however, Jeerson joined Madison in choosing the unconstitutionality of the Bank as his point of at-

tack. Claiming unconstitutionality, Jeerson complained that to treat the establishment of the Bank

as an implied power with regard to the Necessary and Proper Clause was to take possession of a

boundless eld of power, no longer susceptible of any denition or restriction.

11

He would commit

to this argument throughout the National Bank Debate.

Hamiltons response to Jeerson and Madisons criticisms was as convincing as it was elo-

quent. He stressed the idea that granting implicit Congressional powers to create corporations, like

the Bank, would not lead to unlimited Federal powers as Jeerson and Madison feared. He oered

the example that Congress could not incorporate a Philadelphia police department because [it is]

not authorized to regulate the government of localities. However, since Congress is authorized to

regulate trade and collect taxes, it could employ all means which relate to its regulation to best and

greatest advantage. is was a clear distinction of constitutional powers for Hamilton, and incorpo-

rating a National Bank was entirely compatible with this view.

12

Furthermore, legislation based on implied powers was a constitutional norm at the time.

No state Constitution explicitly mentioned bank incorporation, and yet the states had managed to

erect banks without restriction. e national legislature itself had often acted without explicit consti-

tutional authority or ironclad necessity by creating light houses, buoys, beacons, public piers, and

the like. Why should the National Bank be treated any dierently when it came to constitutional

validation? After all, not only states but other nations as well exercised implied powers routinely for

their benecial gains. us, for Hamilton, the reality was that a National Bank would not lead to

unrestricted Federal powers. However, the striking down of the constitutionality of the bill would

indeed suppress the potential of the federal government, and it would also run counter to existing

practices.

13

President George Washington was initially hesitant to sign the Bank bill, and asked his

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

24

Mereminsky Caring for the Constitution

25

cabinet members to submit opinions on the matter. Jeerson wrote a solid opinion but was outdone

by Hamiltons swift 15,000-word response. Washington was convinced. He signed the bill into law

on April 25, 1791, much to the dismay and horror of Madison and Jeerson.

14

Historians and political scholars alike tend to take the same approach toward analyzing

Jeerson and Madisons opposition to the National Bank. is approach asserts that Jeerson and

Madisons strongest and most signicant genuine criticism of the Bank was that they viewed it as un-

constitutional. is idea demonstrates the common historical belief that Madison and Jeerson were

legal supporters of an enumerated powers approach to constitutional interpretation in the National

Bank Debate. Examples of this majority historical opinion can be found in the writings of Merrill

Peterson, Richard Brookhiser, James Roger Sharp, Richard Hofstadter, Gordon Wood, and many of

their esteemed colleagues. Generally, historians group Madison and Jeersons concerns with Ham-

iltons Bank under the umbrella of constitutional criticism. e following are examples of the way in

which scholars characterize Madison and Jeersons opposition:

It was precisely on this ground [constitutionality] that Madison fought the Bank Bill in Congress and that

Jeerson, upon its passage, sought its defeat at the hands of the President.

15

In his report, Madison let all the Republican Partys hobby horses out for a ride. Hamiltons Bank of the

United States and his Report on Manufactures were as unconstitutional as the Alien and Sedition Acts.

16

Jeerson, of course, never gave up his hostility to banks, and he saw in the Bank of the United States, which

he still believed to be unconstitutional, a rival political force of great potentiality.

17

Even when scholars grant the possibility that Madison and Jeerson had other worthy concerns with

the Bank, they typically do so under the assertion that these other concerns were not as signicant:

Both Virginians, although they primarily opposed the Bank on Constitutional grounds, were also

disturbed by what the establishment of the Bank seemed to represent

18

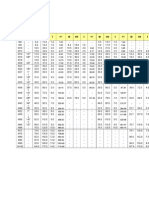

In fact, a quantitative investigation of how much time historians devote to these charac-

terizations paints a telling picture. I have recorded numerous historical accounts of Madison and

Jeersons opposition to the Bank, and it is clear that prominent scholars like Stalo, Brookhiser,

Peterson, and Wood devote much more time to constitutional criticisms made by Madison and Jef-

ferson rather than concerns of any other kind. To illustrate this, I aim to show the contrast between

how many paragraphs these authors allow for describing constitutional criticisms as opposed to other

qualms. If a paragraph includes both constitutional and non-constitutional reasons of opposition,

I did not count it barring one exception: if the author explicitly states that constitutional concerns

were primary. In these cases, I added the paragraph to the count of described constitutional opposi-

tion (i.e. Sharps e major objection he raised, however was a constitutional one p. 39). I did

not nd any examples of an author describing both constitutional and non-constitutional opposi-

tion with an explicit armation that the non-constitutional concern was primary. is quantitative

analysis shows that Stalo devotes 11 paragraphs to Madison and Jeersons constitutional arguments

and only 2 to other concerns. Brookhiser allows 4 paragraphs to the former and only 1 to the lat-

ter. Peterson writes 5 paragraphs about constitutional criticisms and only 2 about other claims, and

Woods score is 4-0 in favor of constitutional arguments as well. erefore, just among this sample of

four highly-esteemed scholars of American history, there are 24 paragraphs describing Madison and

Jeersons opposition to Hamiltons Bank as being primarily constitutional, while only 5 paragraphs

outline other concerns.

19

However, when taking a step back to look at the big analytical picture, this common be-

lief calls many ideas into question. e Constitution was an extremely young document in 1791,

and it would perhaps be hasty to simply assume that Madison, Jeerson (who was not even present

at the Constitutional Convention), and their colleagues were tremendously committed to all of its

various facets as a source of supreme national legal power. is is not to say that they would not be

entirely devoted to its major fundamental freedoms and rights. Yet a total devotion to or a particular

interpretation of something like the Necessary and Proper Clause would not necessarily be a forgone

conclusion, especially for someone like Jeerson who proposed that the Constitution be rewritten

every 20-30 years. If Madison and Jeerson thought the Bank to be corrupt and economically un-

sound, why would they choose to dwell so much on the fact that it was unconstitutional? Would it

not be smarter to point out its economic and philosophical deciencies, which many people would

arguably care more about than the idea that the Bank deed an enumerated powers interpretation of

a yet untested Constitution?

Of course, historians and scholars believe that Madison and Jeerson cared so much about

the Banks unconstitutionality because this is what Madison and Jeerson themselves reiterated so

often in speeches and writings. But any thorough historical analyst knows to look past the surface

of what these political leaders were saying and deep into what their true intentions were. e reality

is that in 1791, Madison and Jeerson had two available paths of opposition against the Bank: the

political-economic path and the legal path. ey chose the legal path, which is surprising given the

strength of the alternative and the potential controversiality of the topic of constitutional legality of

the Bank. Yet many scholars seem to ignore this curious choice and faithfully trust that strict con-

structionism was the core principle of Madison and Jeersons intentions.

A more thorough investigation of the National Bank Debate merits a reconsideration of

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

26

Mereminsky Caring for the Constitution

27

ries, as well as the sectional divides that existed in the United States at the time. In practical terms,

Madison and Jeerson did not just stand on the opposing side of Hamilton in relation to the Bank,

but also to his general economic and legal approaches to running the American republic. It may be

useful to distinguish between the two main areas of disagreement between these men. e rst is the

political-economic realm, where Jeerson and Madison fought tooth and nail for a virtuous America

and against what they viewed as Hamiltons industrial sinkholes of corruption and fraud. Meanwhile,

Hamilton had no qualms about discarding the classical republican concept of virtue in order to

strengthen the American economy in the best way he saw t: manufactures.

e second realm of conict between Hamilton and his two adversaries was the legal arena.

Here, Hamilton called for an implied powers interpretation of the Constitution while Madison and

Jeerson feared that this view would lead to the worst kinds of unlimited Federal power.

Why would Madison and Jeerson use the second realm of legal reasoning to attack Ham-

iltons Bank when the rst political-economic arena would be relevant in a society constantly torn

between the economic virtues of the past and modern commercialism? Were they sincere in making

this choice, or were their legal constitutional criticisms of the Bank a mask for their true political-

economic convictions?

Economic Context e Spectrum

During the National Bank Debate, the political model widely held to be most eective for

a nation of free men, rid of any tyrannical oppression, was republicanism. Many versions of republi-

canism entered political and economic discussion, and men of various beliefs proclaimed themselves

to be republicans. Yet republicanisms common denominator at all stages was the idea that freedom

ultimately meant the lack of arbitrary power. A commitment against arbitrary power was crucial and

could be eectively accomplished through virtuous practices aimed at achieving the public good.

20

is assertion also had implications in the economic realm as well as on the political-economic poli-

cies that Madison, Jeerson, and Hamilton individually supported.

In the ancient world, the word Free, in a republican sense, described a particular social

class men who were not slaves or serfs. e word also referred to the type of virtue and character

these men were supposed to reect. Ultimately, a Free Man was independent and self-sucient.

Ancient Greco-Roman society saw freedom as an extremely exclusive privilege. Subordinate classes of

men (serfs, slaves) supposedly lacked the ability to be virtuous. Moreover, they regularly performed

commercial and menial labor work that killed virtue and corrupted the individual. us, only men

who did not shoulder the burden of this corruptive labor or free men could truly possess the type

the modern historical analysis and, ultimately, a modication. In reality, constitutionality was nei-

ther Madison nor Jeersons greatest qualm about the Bank, nor was it as important to them as their

fears of the Banks corruptive and economically unsound consequences. In fact, they were not legally

committed to the Constitution in the context of the Bank debate nearly to the extent that historians

claim. is is not to say that they were not dedicated to fundamental constitutional principles and

freedoms. is thesis certainly does not make such a bold and exaggerated assertion. However, it

does assert that Madison and Jeerson were not sincere legal proponents of an enumerated powers

interpretation of the Necessary and Proper Clause as it pertained to the Bank bill. In this context, an

enumerated powers approach was rather an instrumental means to an end, not Madison and Jeer-

sons fundamental goal. eir true goal was to build a political-economic framework for their respec-

tive, ideal American republics. Both Madison and Jeersons plans for the future absolutely required

an enumerated powers interpretation, or else this ideal republic would fall apart economically. ey

also needed to convince their audience, President Washington, of the Banks deciencies and probably

thought it more prudent to do so through legal arguments. Consequently, they needed Washington

to ensure that the enumerated powers view in constitutional interpretation emerged victorious in the

National Bank Debate and that a Hamiltonian implied powers view would die with the Bank bill.

erefore, I will argue that Madison and Jeersons claims of unconstitutionality against

the National Bank did not represent their true, signicant, ideological qualms with Hamiltons Bank

bill nor a deep legal commitment to an enumerated powers approach to the Necessary and Proper

Clause; instead they represented Madison and Jeersons knowledge of their audience and their per-

sonal desires to promote the enumerated powers approach as an instrumental policy in light of their

ultimate political and economic goals.

If Madison and Jeersons opposition to the Bank centered on a disingenuous claim for

unconstitutionality, the implications for todays constitutional discussion would be signicant. e

National Bank debate was one of the rst truly noteworthy disputes regarding the constitutionality of

a piece of legislation. As a momentous historical event, it inuenced the amount of weight that the

modern American government places on constitutionality. If Madison and Jeerson were insincere

in their calls for an enumerated powers interpretation, todays strong emphasis on the Constitution as

a legal pinnacle although justied may be based on a false understanding of history.

Context for the Debate and the Oppositions Arguments

In understanding the National Bank Debate and why certain aspects of it were surprising,

one must rst understand its context. is includes the prevalent economic and constitutional theo-

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

28

Mereminsky Caring for the Constitution

29

of virtue that classical republican ideals required.

21

As history wound its way into the eighteenth century, dierent interpretations of repub-

licanism had a massive eect on scholars and politicians perceptions of rapidly commercializing

society. inkers like Rousseau and Jeerson looked to ancient Roman history for guidance on how

to preserve republican liberty and avoid tyranny. Under the right set of conditions for political insti-

tutions, these men believed that the classical republican ideal of a virtuous citizenry working for the

public good was still very much possible even in a society bent on industrialization and manufactures.

Montesquieu, Smith, and Hamilton disagreed with this approach. ey thought that a reliance

on ancient history for lessons on republicanism was useless because modern commercial societies

confronted entirely dierent challenges than those of ancient Greece and Rome. It was in these new

challenges of the eighteenth century that Hamilton, for example, looked for commercial resources

that would enhance a republican character within the US by freeing it from a dependence on foreign

economic powers.

22

For the purposes of this thesis, it is useful to locate Madison, Jeerson, and Hamilton on

a political spectrum of republican thought. Jeerson was a man whom it is best to describe as a tra-

ditional republican one who valued agrarian virtue over commercial industrialization and desired

autonomy and freedom for agricultural producers from the Northern cities of the manufacturers.

ese cities Jeerson saw as corrupt and fraudulent, and their control over agrarian economic virtue

was exactly the type of arbitrary power he wished to avoid. In this sense, Jeerson subscribed to the

classical republicanism of ancient Greece and Rome described above. He also borrowed much of his

ideology from the doctrine of physiocracy, as described by Ronald Meek:

e Physiocrats main aim was to illuminate the operation of the basic causes which determined the general

level of economic activity. For this purpose, they believed that it was useful to conceive economic activity

as taking the form of a sort of circle, or circular ow as we would call it today Within this circle, the

Physiocrats then endeavoured to discover some key variable, movements in which could be regarded as the

basic factor causing an expansion or contraction in the dimensions of the circle, i.e. in the general level of

economic activity. e variable they hit upon was the capacity of agriculture to yield a net product.

23

Agriculture and agriculture alone yielded this net product, was morally and politically superior to

all other forms of economic output, and thus made land the most indispensable commodity in the

physiocratic system.

24

Hamilton stood on the other end of the republican spectrum. He was not concerned with

battling corruption to preserve virtue. To rescue the country from succumbing to arbitrary power in

the form of foreign market control, Hamilton aimed to strengthen the economy through manufac-

tures and an elaborate system of debt relief, which of course included the incorporation of a National

Bank. In many respects, Hamilton was an anomaly he had succeeded in discarding the traditional

republican heritage that had so heavily inuenced the Revolutionary mind.

25

If America could stand

its ground against foreign competitors in international trade as a result of its prosperous economy,

Hamilton did not so much care if this economy was built on a somewhat corrupt foundation. A

focus on agricultural virtue could be enough to sustain an American economy, but Hamilton wanted

economic glory and rm independence from foreign economic inuence, which required a more

industrialized approach. ese were republican goals in themselves, although they lay on a dierent

part of the republican political spectrum than Madison and Jeersons.

Madison fell somewhere in the middle of these two adversaries on the spectrum of re-

publican thought. He certainly embraced economic prosperity in the form of manufactures, but he

dreaded the destruction of agrarian principles. He also battled ambivalence toward the economic

theory that was rising in dominance in America: mercantilism. Although Madison claimed that he

wished to free America from the oppression of mercantilism, he nonetheless espoused a highly mer-

cantilist policy of commercial discrimination in foreign trade. As he tried to reconcile these opposing

motivations, other theorists, too, considered and rejected mercantilist principles.

Economic Context Discourse Leading up to 1791

In the late eighteenth century, mercantilism posed a heavy challenge to traditional agrarian

principles of republicanism. Philipp Wilhelm von Hornick comprehensively summarizes its nine

major tenets:

at every inch of a countrys soil be utilized for agriculture, mining or manufacturing.

at all raw materials found in a country be used in domestic manufacture, since nished goods have a

higher value than raw materials.

at a large, working population be encouraged.

at all export of gold and silver be prohibited and all domestic money be kept in circulation.

at all imports of foreign goods be discouraged as much as possible.

at where certain imports are indispensable they be obtained at rst hand, in exchange for other domestic

goods instead of gold and silver.

at as much as possible, imports be conned to raw materials that can be nished [in the home country].

at opportunities be constantly sought for selling a countrys surplus manufactures to foreigners, so far

as necessary, for gold and silver.

at no importation be allowed if such goods are suciently and suitably supplied at home.

26

To more and more Americans the traditional mercantilist assumption that manufactures were nec-

essary to maintain industry and full employment, heretofore considered relevant only to Europe,

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

30

Mereminsky Caring for the Constitution

31

seemed suddenly and ominously relevant [in America], explains Drew McCoy.

27

In fact, according

to William Appleman Williams, the central characteristic of American history from 1763 to 1828

was the development and maturation of American mercantilism.

28

It is easy to confuse Americas

rebellion against Britain as a rebellion against mercantilism as well, but this would be a mistake. In

truth, post-revolutionary American hopes for empire actually stemmed from mercantilist inclinations

acquired from and maintained after British colonial rule.

29

Mercantilism was a crucial tenet for people like Madison who worked within a nation-

alistic framework to build a balanced, dynamic, agricultural, and commercial economy based on

capitalism. Whether agrarian or urban, mercantilists were essentially nationalists who strove for self-

suciency through increased domestic production and a favorable balance of trade, says Williams.

Self-suciency was another political element that constituted an essential republican goal of freedom

from arbitrary power. Mercantilists concentrated on production along with the regulation of export

markets and sources of raw material. us, their focus shifted from consumption and economic

interdependence, to fears of decits as an indicator of economic crisis. is can be seen in Madisons

commercial discrimination policy that fervently aimed to restore a favorable balance of trade for the

US and to control foreign export markets by opening up more natural channels for American trade.

Export more and import less, mercantilists said, and it seemed as though America listened.

Yet many economists did not listen but rather rebelled against mercantilism and traditional

agrarian-focused republicanism both, and with a vengeance. Philosophers like Adam Smith and

David Hume asserted that the pursuit of individual private interest was the best and most ecient

method of enhancing the public good (instead of the republican pursuit of collective societal virtue).

Hume encouraged the pursuit of luxury, framing it as both an inevitable and rening human action,

rather than as a degrading behavior of selsh men. e desire for luxury was an industrial stimulus,

and it would be futile to try to stamp it out, while properly harnessed, it opposed indolence and

encouraged men to work harder.

30

Meanwhile Smiths challenges to mercantilism were also striking. He explained that the

main benet of foreign trade was not the importation of gold and silver, but the carrying out of

surplus produce for which there is no demand and bringing back something for which there is. He

continued to denounce the mercantilist claim that the importation of gold and silver was necessary

to maintain a strong America. Smith postulated that e nation which, from the annual produce of

its domestic industry, from the annual revenue arising out of its lands, labour, and consumable stock,

has wherewithal to purchase those consumable goods in distant countries, can maintain foreign wars

there, and can thus maintain its strength.

31

One of Smiths greatest contributions to economic thought was his emphasis on the Di-

vision of Labor principle: the more specialized the task of each individual laborer, the greater the

economic output. e establishment of this principle with respect to foreign markets directly contra-

dicted the essential mercantilist tenet of favoring exports. Calvin Johnson explains, once free trade

replaced mercantilism as an economic philosophy importing British woolens and other manu-

factured goods came to be seen as a wise decision to buy the highest quality goods at the best price

abroad, rather than wasting resources doing an inferior job more expensively at home.

32

ere existed also a split not simply between theoretical principles but also between geo-

graphical locations. e Northern and Southern sections of the United States were constantly at odds

with each other, and these arguments stemmed from both economic disagreements and a Southern

perception of commercial favoritism by the government toward the North . Jeerson was the voice of

the Southern struggle against a federal government lled with the likes of Hamilton who (in his view)

blatantly favored Northern manufacturers and nanciers over noble Southern agricultural producers

the virtuous yeomen. Factory-run cities and corruption threatened the Southern republican charac-

ter by forcing producers to become dependent on commerce and manufactures in order to participate

in a swiftly industrializing American economy. is dependence led to a loss of autonomy, and the

vicious cycle continued.

Moreover, the South resented the Northern condemnation of slavery. Republicanism and

true civic participation required that menial labor be left to the slaves so that the free Southerners

could perform their political duties unburdened. Here stood the Northerners, with Hamilton as

their face, championing commercial progress and an industrialized society that they wished to impose

on the South. Meanwhile, the Southerners, forced to accept dependence on the North, would even

further have to decrease agricultural productivity and self-suciency by giving up slavery. is was a

set of conditions that the South and Jeerson simply were not willing to accept.

33

e Political-Economic Discourse in 1791

As free trade principles began to overtake mercantilist leanings, and as both challenged the

predominant traditional agrarian republican theories of the past, the Founders tried to balance the

young economy between modernization and a deeply ingrained commitment to virtue.

By the 1791 National Bank Debate, proponents of traditional republicanism confronted

a dicult challenge in the face of new free trade and mercantilist interpretations of republicanism.

ey had to reconcile their support for a theory focused on the virtuous pursuit of the public good

with Smithian endorsements of self-interest economics. As already mentioned, classical republi-

Journal of Politics and International Aairs Volume V Issue I Winter 2013

32

Mereminsky Caring for the Constitution

33

canism, throughout all of its historical stages and alterations, espoused the freedom from arbitrary

power.

34

How could this republicanism survive in a world where Adam Smiths free market Invisible

Hand was the epitome of an unimpeded, arbitrary power? As Drew McCoy explains, American

revolutionaries enthusiastically embraced the republican spirit of classical antiquity that expressed

virtue in terms of a primitive economy, but they also seemed to realize that this spirit had to be ac-

commodated to their own dynamic world of commercial complexity.

35

In a way, omas Jeerson

became the face of this struggle. He found himself in a political arena that was hurtling through

commercialization while he remained committed to agrarian virtue and anticorruption.

Merrill Peterson explains that there were many aspects of the Hamiltonian policy prefer-

ences that troubled Jeerson, and most troubling at the time were economic factors surrounding the

National Bank. But besides the immoral, corrupting economic whirlwind that would surround the

creation of the Bank, what Jeerson protested against the most was the length of the Bank charter.

e enduring Bank charter would only exacerbate the sectional imbalances that would result from its

policies, and it would do so for a seemingly unending eleven years. For eleven years, this Bank would

serve as a helper to Northern merchant economies and as a detriment to Southern planters, farmers,

and men of agrarian virtue. Jeerson was truly alarmed by these politics of inequity. He had always

been plagued by the favoritism the national system aorded to Northern industry at the expense

of Southern agricultural producers. e Bank would become another tipping point in favor of the

North. When it came to the Bank, Jeerson could not approve of the measure in the abstract or in

the face of the Constitution; even more, he was convinced it was politically unsound, and he would

not take any responsibility for it.

36

What always made it extremely hard for Hamilton to convince Jeerson of the growing

benets for an industrialized America built on manufacturing was that in Hamiltons own words

Jeerson thought, as did many physiocrats of the time, that agriculture [was], not only, the most

productive, but the only productive species of industry.

37

Jeerson viewed land as the only valuable

economic resource, while commerce and manufactures just altered part of this value into other forms.

is transformation, however, added no value of its own. Industries, Jeerson viewed as sinkholes of

vice and corruption. In general, urban industrial development was a blight to be avoided, and if this

was not possible, at least postponed. Instead of setting urban industrial development as a national

objective, the country would fare better by focusing on westward expansion. In order to avoid cor-

ruptive industrial development, Jeerson rst had to defeat the National Bank bill, the most insidi-

ous engine of Hamiltons entire economic system that would surely lead America to its ruin.

38

Hamiltons policies, especially as seen in the Bank bill, completely negated the Jeersonian

vision. ey would enrich northern nanciers and speculators, and therefore the North instead of

the (as Jeerson saw it) virtuous agrarian South would gain disproportionate standing in the nation-

al government; Northern urban development would draw capital away from westward agricultural

expansion through the stimulation of manufactures. e moment when Jeerson realized the scope

of the threat that Hamiltons political economy posed, with the Bank serving as a microcosm of the

general anti-republican character of Hamiltons policies, was the moment when Jeerson abandoned

his usually timid political presence and fully entered the conict against the Bank.

39

Although Madison ultimately took Jeersons side in the National Bank debate, his politi-

cal-economic policy preferences were not as hostile to commercialization and industrialization as were

Jeersons. Yet Madison was in no way a proponent of the type of commercial society Hamilton had

in mind, and in some ways, he tended to revert to the republican virtue that Jeerson so passionately

espoused as well. Madison had a particularly interesting set of ambitions for the young republic,

preferring for America to develop across space rather than time. In other words, he believed the

American economy would prosper more quickly if American producers also occupied western territo-

ries. With more land to work with, the limitations of time would not be so great to a much expanded

American economic potential of output. Madison explained, if America could continue to resort to

virgin lands while opening adequate foreign markets for their produce, the US would remain a nation

of industrious farmers who marketed their surpluses abroad and purchased ner manufactures they

desired in return. Madison wholeheartedly supported this form of social development as did Adam

Smith because this was a policy that agreed with the natural law of the free market. e policy

represented noninterference with the market, and if America could benet economically without