Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Estonia Relations Between Christian and Non-Christian Religious

Estonia Relations Between Christian and Non-Christian Religious

Uploaded by

Dean DoyleCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Bristol 1st DegreeDocument34 pagesBristol 1st DegreeOmer Tecimer100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Theology of Missions PaperDocument11 pagesTheology of Missions Paperjohnnyrod1952100% (2)

- Collis and Bayer - Initiating The Millennium PDFDocument1 pageCollis and Bayer - Initiating The Millennium PDFBob CollisNo ratings yet

- AH The Greatest Coincidence in HistoryDocument6 pagesAH The Greatest Coincidence in HistoryBCNo ratings yet

- Conditional ForgivenessDocument3 pagesConditional Forgivenesskal6800No ratings yet

- First MassDocument35 pagesFirst MassFarah Jaye Verde Cayayan100% (3)

- The Kingdom of BloodDocument17 pagesThe Kingdom of BloodIsaque Resende100% (1)

- Translation of Monoliths by AH Lyngdoh (Partial)Document1 pageTranslation of Monoliths by AH Lyngdoh (Partial)Roger Manners100% (1)

- Sep 2017Document63 pagesSep 2017Natacia Rimorin-DizonNo ratings yet

- Acts 10 - (4 23-31) - When The Church PraysDocument13 pagesActs 10 - (4 23-31) - When The Church PraysMisaelPeixotoNo ratings yet

- Craig Simonian - On The Baptism of The Holy SpiritDocument13 pagesCraig Simonian - On The Baptism of The Holy SpiritjrcjejjNo ratings yet

- Morgana's Alter Ego - Doc 1Document10 pagesMorgana's Alter Ego - Doc 1matchmaker016No ratings yet

- Epc Leadership Training GuideDocument188 pagesEpc Leadership Training GuideJoseAliceaNo ratings yet

- Dan 11 40 45significance PDFDocument72 pagesDan 11 40 45significance PDFVlad BragaruNo ratings yet

- Frans J. Los - The FranksDocument114 pagesFrans J. Los - The FranksArchiefCRNo ratings yet

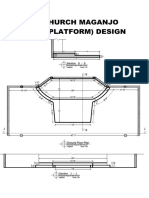

- Sda Church Maganjo Pulpit (Platform) Design: Section S - SDocument1 pageSda Church Maganjo Pulpit (Platform) Design: Section S - SYosamuKigongoNo ratings yet

- Semi ArianismDocument4 pagesSemi ArianismJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Prayer For Newly Ordained Priests: Prayer For The 2018 Year of The Clergy and Consecrated PersonsDocument1 pagePrayer For Newly Ordained Priests: Prayer For The 2018 Year of The Clergy and Consecrated PersonsNestor JrNo ratings yet

- My Life and EthiopiaDocument200 pagesMy Life and EthiopiaEd HowardNo ratings yet

- Advanced/Intermediate DB Rejoice (Sinach)Document2 pagesAdvanced/Intermediate DB Rejoice (Sinach)Tendai MandibatsiraNo ratings yet

- Lion & Serpent: In, Ivxv - Volume 12, Number 1Document40 pagesLion & Serpent: In, Ivxv - Volume 12, Number 1Max anykey100% (1)

- Module 4Document18 pagesModule 4Christian Diki JooeNo ratings yet

- Bernardus Claraevallensis - de Laude Novae Militiae Ad Milites TempliDocument30 pagesBernardus Claraevallensis - de Laude Novae Militiae Ad Milites Templimanlio_peruginiNo ratings yet

- GospelBroadcastingMission 1979 USA PDFDocument22 pagesGospelBroadcastingMission 1979 USA PDFthe missions networkNo ratings yet

- Reinking The Truth About 666Document2 pagesReinking The Truth About 666Chevy ChippyNo ratings yet

- History of The PapacyDocument387 pagesHistory of The PapacyJesus Lives100% (1)

- Holy Rosary GuideDocument30 pagesHoly Rosary GuideFelix Soliva GudelosaoNo ratings yet

- A Concise Catalogue of The European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtDocument112 pagesA Concise Catalogue of The European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtMonica BîldeaNo ratings yet

- SWRB Puritan Hard Drive CategoriesDocument4,538 pagesSWRB Puritan Hard Drive CategorieswdeliasNo ratings yet

- March 2016 EpistleDocument26 pagesMarch 2016 EpistleBradford Congregational ChurchNo ratings yet

Estonia Relations Between Christian and Non-Christian Religious

Estonia Relations Between Christian and Non-Christian Religious

Uploaded by

Dean DoyleOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Estonia Relations Between Christian and Non-Christian Religious

Estonia Relations Between Christian and Non-Christian Religious

Uploaded by

Dean DoyleCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [TBTAK EKUAL] On: 2 September 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription

number 772815468] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Religion, State and Society

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713444726

Estonia: Relations between Christian and Non-Christian Religious Organisations and the State of Religious Freedom

Triin Vakker; Priit Rohtmets

Online Publication Date: 01 March 2008

To cite this Article Vakker, Triin and Rohtmets, Priit(2008)'Estonia: Relations between Christian and Non-Christian Religious

Organisations and the State of Religious Freedom',Religion, State and Society,36:1,45 53

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09637490701809712 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09637490701809712

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Religion, State & Society, Vol. 36, No. 1, March 2008

Estonia: Relations between Christian and Non-Christian Religious Organisations and the State of Religious Freedom1

TRIIN VAKKER & PRIIT ROHTMETS

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

ABSTRACT In this article we examine the religious situation in postsoviet Estonia. Traditionally a Christian country, Estonia today is strongly inuenced by its Soviet past. Only one third of the population belongs to a particular religion, while nearly half the population say that religion plays no role in their lives. The states attitude towards the various religions is remarkably positive and the legislation concerning religious organisations is very liberal. Most believers in Estonia belong to Lutheran and Orthodox churches. The biggest non-Christian religion is Estonian Native Religion, and there are also Buddhist, Jewish and Muslim communities. In the late 1990s several problems arose concerning legislation and religious studies at schools. Discussion of these topics found the Christian denominations on one side and non-Christian religions on the other. Although the question whether Religious Studies should be a compulsory subject in schools is still fervently disputed, this now happens in the secular media, while discussion has more or less ceased amongst the various religions. The dialogue between Christian and non-Christian religions is nearly nonexistent and there seems to be no will to intensify interrelations. If problems emerge, the representatives of the various religions turn to the state rather than discuss them among themselves.

Introduction The aim of this article is to give an overview of religious organisations registered in Estonia, of the contacts among them and of their relationships with the state. Just 29 per cent of the respondents in the 2000 census said they adhered to a particular creed, while 34 per cent said they were indierent to religion and 6 per cent said they were atheists.2 In a poll in 2002 only 15.2 per cent of respondents said that religion played an important role in their everyday life, while 28 per cent said that religion had no importance for them at all, and 2.3 per cent were negative towards religion, one reason commonly given being too aggressive mission work (Kilemit and No mmik, 2004, pp. 14 16). The percentage of atheists and people hostile towards religion is about the same as in Nordic countries, but there is a relatively large number of people who are indierent or somewhat hostile towards religion, and this results in a generally rather negative attitude in Estonian society to initiatives taken by the various religious organisations.3 Religious organisations are clearly divided into two groups: Christian organisations on one side, and all other religions registered in Estonia on the other. Christian

ISSN 0963-7494 print; ISSN 1465-3974 online/08/010045-09 2008 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/09637490701809712

46

Triin Vakker & Priit Rohtmets

organisations are gathered under the umbrella organisation the Estonian Council of Churches (ECC) (Eesti Kirikute Noukogu), which is partly funded from the state budget. In order to present their views more successfully, on 20 April 2001 the representatives of non-Christian religions established the Round Table of Religious henduste U marlaud). Organisations (RTRO) (Usuliste U Christian Organisations and the Council of Estonian Churches The biggest religious organisation in Estonia is the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church (EELC) (Eesti Evangeelne Luterlik Kirik).4 It has about 160,000 members of whom about 40,000 are active.5 (In 2003 the total population of Estonia was 1,356,000.) The Lutheran Church has been the predominant church in Estonia since the beginning of the sixteenth century. Estonia became part of the Russian Empire in the early eighteenth century, and for a long time the EELC functioned according to Russian regulations on religion. After the February Revolution of 1917 in Russia the Estonians were able to hold their rst church congress (in May). The delegates wanted a free church separated from the state, and referred to the EELC as a free peoples church (vaba rahvakirik). The congress set up a committee which developed a new statute for the EELC; this was adopted in 1919. Until 1940, with over 900,000 members, the EELC played an extremely important role in Estonian society, with clergy elected to parliament. Estonia became part of the Soviet Union in 1940, and thereafter the number of members of the EELC fell drastically, the church was dispossessed of its assets, half the clergy ed to the West, and most of those who stayed in Estonia fell victim to repressions. Membership began to grow again in the late1980s, coinciding with Estonias struggle for freedom. The number of members reached its peak in 1992, and since then it has continually fallen, but the EELC is still the largest religious organisation in Estonia. It has its own newspaper and a theological institute for its ministers. Over the centuries Orthodoxy has also consolidated its position in Estonia. In 1920 the Orthodox Church in Estonia became an autonomous church under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate. When Bolshevik persecution of the Orthodox Church set in, involving the death of the Estonian bishop Platon and the imprisonment of Patriarch Tikhon, the council of the church decided to ask to be taken under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople. The transfer took place in 1923. During the rst Soviet occupation in 1941 the Orthodox Church was united with the Moscow Patriarchate, but this was annulled after the Germans occupied Estonia in the same year. After the second Soviet occupation of Estonia, in 1944, and under pressure from the Soviet government, the Orthodox Church in Estonia came back under the control of the Moscow Patriarchate. Many members of the church, however, left the country and established an Estonian Orthodox Church in Exile, which continued to maintain ties with Constantinople. Thus two opposed groups rst appeared within the Estonian Orthodox Church. Estonia regained its independence in 1991 and in 1993 the exile church, now called the ~ Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church (EAOC) (Eesti Apostlik Oigeusu Kirik) (known ocially in English as the Orthodox Church of Estonia) was registered and recognised is the legal successor of the church of the Russian Empire. Protests from the Moscow Patriarchate led nally to the registration of the Estonian Orthodox ~ Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (EOC-MP) (Moskva Patriarhaadi Eesti Oigeusu Kirik) in 2002. Thus two Orthodox Churches are registered in Estonia today (Ringvee, 2003).

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

Estonia: ChristianNon-Christian Relations

47

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

During the period while Estonia was part of the Soviet Union the Russian population of Estonia increased signicantly, with the result that today the EAOC has about 25,000 members, while the EOC-MP has close to 150,000 members. Services in the former are conducted in Estonian; those in the latter mostly in Russian. The membership of other religions is smaller. The other churches registered in Estonia are: the Roman Catholic Church (Rooma-Katoliku Kiriku Apostellik Administratuur Eestis) (about 6000 members); the Union of Free Evangelical and Baptist Churches of Estonia (Eesti Evangeeliumi Kristlaste ja Baptistide Koguduste Liit) (also about 6000 members); the United Methodist Church in Estonia (Eesti Metodisti Kirik); the Estonian Pentecostal Church (Eesti Kristlik Nelipuhi Kirik); the Estonian Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (Adventistide Koguduste Eesti Liit); the Estonian Congregation of St Gregory of the Armenian Apostolic Church (Armeenia Apostliku Kiriku Eesti Puha Gregoriuse Kogudus); and the Charismatic Episcopal Church of Estonia (Eesti Karismaatiline Episkopaalkirik). In 1989, when the states attitude towards religious organisations had grown considerably more tolerant, the members of six creeds formed the ECC as a vehicle enabling its members to relate to the state and express their opinions more clearly. Today the ECC has ten member churches (all those listed above).6 The main challenges facing the ECC are developing ecumenical work and solving problems in the area of religious education. The ECC also plays an important role in training prison and army chaplains, and conducts socio-religious studies on the moral and other values of Estonians. It has developed into an active partner with the state. It has regular meetings with representatives of state institutions with the aim of contributing to legislative work. Non-Christian Religious Organisations and the Round Table of Religious Organisations A wide range of non-Christian world religions is registered in Estonia, but their membership is well below that of the Christian churches. According to the census of 2000 there were 1387 Muslims in Estonia. They form two congregations. The Estonian Islamic Congregation (Eesti Islami Kogudus), registered in 1994, sees itself as the legal successor of the congregation in Narva that was established in 1928. Muslims have thus been in Estonia for a long time, and have a positive attitude towards Estonian culture. For example, according to the statute of the Estonian Islamic Congregation, one of their main tasks is to promote positive attitudes towards the Estonian national cultural heritage and traditions as well as to help the members of the congregation to integrate into Estonian society through the Estonian language, history and traditions (Linnas, 2004, p. 41). The Estonian Sunni Congregation (Eesti Muhameedlaste Sunniitide Kogudus) was registered in 1995. It was established by a group of former members of the Estonian Islamic Congregation as a result of personal dierences and conict between two ministers. Estonian Sunnis and Shiites work together, however. Most Muslims in Estonia are Sunnis; most of the Shiites are Azerbaijanis. According to the census of 2000 there were 622 Buddhists in Estonia, although the active membership of the two registered congregations seems to be no more than 100. There is a non-prot Buddhist organisation called The Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (Laane Budistliku Vennaskonna Sobrad). Many members of the Buddhist congregations are socially active, but congregations as such tend not to be socially involved, apart from their membership of the RTRO (Po lenik, 2004, p. 92).

48

Triin Vakker & Priit Rohtmets

In addition to the Muslims and Buddhists the non-Christian religious organisations registered in Estonia include the Jewish Religious Community of Estonia (Eesti Juudiusu Kogudus), the Union of Estonian Jewish Congregations and Organisations (Eesti Juudi Koguduste ja Organisatsioonide Liit), the Congregation of Krishna Consciousness in Estonia (Krishna Teadvuse Eesti Kogudus), the Union of Estonian Bahai Congregations (Eesti Bahai Koguduste Liit), the Estonian Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist Congregation (Tiibeti Budismi Nyingma Eesti Kogudus) and the Estonian House of Taara and Native Religions (Maavalla Koda). The latter regards the native Estonian religion as embodying the centuries-long Estonian cultural tradition; it holds that Christianity was forced upon the Estonians and is not natural for them (Maausust, n.d.). The movement started in the late 1980s, when a group of history students began studying sacred groves. It continues to grow, and now has the largest number of members among the non-Christian organisations (about 1500). One reason for this is certainly the fact that it is the most active of the non-Christian religions; it says that it tries to oppose the domination of the Christian churches (Press Release, 2002).7

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

Relations between the Christian and non-Christian Religious Organisations and their Relations with the State According to Ilmo Au, the head of the Religious Aairs Department of the Estonian Ministry of Interior Aairs (Eesti Vabariigi Siseministeeriumi usuasjade osakonna juhataja), the situation in Estonia is unique, because all religious organisations are able to work together. If dierences exist, they arent emphasised and they dont form the basis of conicts and intrigues. Mr Au also notes that a situation in which Sunnis and Shiites can work together is quite unusual. According to him all this is an excellent example of the eects of democratic policies and very good legislation (Eestis, 1995). Estonia has been very highly rated in international studies as well. The Churches and Congregations Act (Kirikute ja koguduste seadus) which was passed on 11 February 2002 has received especially positive feedback. Nevertheless, from time to time the non-Christian organisations protest against alleged religious freedom infringements. In most cases these complaints are made in the form of protest letters from the RTRO; often, however, criticisms are voiced by representatives of individual religions. The House of Taara and Native Religions is denitely the most active in this respect, blaming both the state and the larger (usually Christian) religions for breaching religious freedom or for hidden attempts to establish an Estonian state church. Problems can be divided into two main categories, which are both subjects of discussion in wider Estonian society: (1) problems connected with legislation that is, with religion-state relations; and (2) problems connected with religious education, chaplaincy and alleged attempts by the EELC to gain the status of an Estonian state church that is, with interreligious relations. Problems Connected with Legislation The House of Taara and Native Religions argues in favour of indigenous national religion. It holds that mission work and religious conversion are forms of mental and cultural violence that decrease lifes diversity. It gives examples from history showing that tens of millions of people have been killed and hundreds of peoples and cultures destroyed as a result of missionary activity and religious intolerance over the last millennium. It argues that religious freedom is under threat in Estonia because the

Estonia: ChristianNon-Christian Relations

49

states religion policy is unbalanced, taking account only of the interests of certain Christian organisations, for whom the situation is much better because of state subsidies and support (Usuvabadus, n.d.). According to the RTRO religious legislation in Estonia is based on the arguments and interests of Christian creeds, and several laws have been passed that hamper the practice of other religions (here they apparently mean laws on military and prison chaplains, and also the fact that the ECC is funded from the state budget) (Usuliste, 2002a). Statements of this kind in the Estonian press by representatives of non-Christian religions were especially frequent before the passing of the 2002 Churches and Congregations Act. Non-Christian religious organisations argued that the law was conceived in a Christian context and that they might fail to meet the new registration criteria. Article 7 of the law stipulates that religious organisations must include the words church, congregation, union of congregations or monastery/nunnery (kirik, kogudus, koguduste liit, klooster) in their ocial name.8 In a letter to the legal aairs committee of the Estonian parliament dated 20 February 2002 three nonChristian religious organisations expressed their worries about religious discrimination in Estonia and claimed that the law was not in conformity with the Estonian Constitution and breached internationally recognised human rights norms (Presidendile, 2002). The concerns of the non-Christian religions led them to unite in setting up the RTRO on 29 November 2002. The RTRO has addressed a number of issues. It highlights problems with the media, which are said to broadcast a lot of Christian programmes but to give inadequate coverage to other religions. Another cause for concern is the ocial protocol for celebrating state holidays, which in most cases includes the participation of national leaders in church ceremonies. The RTRO claims that the situation is inappropriate because only one third of the people living in Estonia are Christians; most Estonians, they say, have expressed no religious preference. The RTRO argues that psychologists rather than chaplains should be deployed in the army and prisons, on the grounds that they are religiously impartial (Usuliste, 2002b). It has also addressed issues over religious education in schools: there should be more coverage of the history of religion in a range of subjects, instead of religious studies with an arguably Christian background. The RTRO repeatedly protested to the parliamentary legal aairs committee about the new legislation. The committee did not agree that the word congregation had an exclusively Christian meaning. According to the law a congregation is a voluntary union of individuals practising the same religion, the activities of which are based on its statute. The RTRO then turned to the president of Estonian Republic and the chancellor of justice. As a result a group of experts was convened, and in 2003 it concluded that the terms used in the law, including congregation, had a Christian background and were therefore Christian concepts. The chancellor accepted this conclusion. The head of the department of religious aairs also agreed that the law should be urgently amended so that the register of religious organisations would include other historical terms besides church, congregation, union of congregations and monastery/nunnery (Kaasik, 2003). Parliament passed the amendment in 2004, making it possible for the House of Taara and Native Religions to register their organisation under that name. Problems arising out of the 2002 legislation have thus been overcome and, as far as the nature worshippers are concerned, the only remaining outstanding issue is determining the status and the mapping of their sacred hills, making it possible to treat them equally with churches, mosques and synagogues as sacred locations.

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

50

Triin Vakker & Priit Rohtmets

Thanks to the eorts of the civil servants of the department of religious aairs, however, a preliminary compromise has been reached, according to which the sacred groves will become protected sacred areas. Problems Connected with Religious Studies The question of whether religious studies should be a compulsory subject in Estonian schools has been a source of controversy since the early 1990s. Soon after Estonia regained its independence in 1991 there was widespread support for the idea of introducing religious studies into the school syllabus. Various church bodies began to draft courses. Three syllabi were compiled, in 1991, 1993 and 1997; they were all Christian-based, bearing characteristics of the denominations that compiled them, and although various schools used them none of them gained general acceptance. The question became lively again towards the end of the 1990s, when Tartu University and several churches cooperated to compile a new syllabus for religious studies. The course introduced every major religion, but the compilers considered that because historically Estonia was part of the Christian cultural space it was necessary to concentrate particularly on Christian teachings. There was a widespread response: not only the proposed emphasis on Christianity but also the basic idea of including religious studies in school curricula as a compulsory subject came under criticism. Critics included both non-believers and representatives of non-Christian religions; and while the majority of the opponents of religious studies feared that the aim was to lure schoolchildren to join churches, the complaint of non-Christian believers was that the marlaud, 2001). In the discussion over treatment of other religions was too shallow (U the content and nature of religious studies there were many dierent parties, including the EELC, the ECC and the RTRO, all vigorously defending their own positions. The RTRO submitted its own proposals to all the relevant parties in 2001. It emphasised rst of all that the proposed syllabus was not suitable for schools because it did not take into account the requirements of pupils of dierent ages. The ethics classes proposed for elementary schools, for example, were arguably based on an oversimplied treatment of the Protestant system of ethics. It then went on to point out that there was a lack of teachers and teaching materials capable of sustaining religion as a compulsory subject and that there was a risk that pupils would be misinformed rather than educated. The new subject would also increase the workload of pupils. It also argued that teaching religious studies on the basis of a particular religion was unconstitutional. After these critical observations the RTRO went on to present its own proposals. It recommended increasing the proportion of the social studies syllabus devoted to religion in order to provide a better overview of dierent religions and creeds and their history. It did not exclude the possibility of teaching religious studies in Estonian schools in line with contemporary European standards at some point in the future; but a proper system for training teachers of religious studies needed to be put in place rst. The knowledge of current teachers of religious studies was limited to Christianity, and even here many of them did not have thorough marlaud, 2003). knowledge (U The largest Estonian religious organisation, the EELC, shares the view that pupils should be informed about dierent religions and that the state should guarantee the availability of teaching materials and teachers education (EELK, 2002). Unlike the Round Table, however, the EELC argues that religious studies should be a compulsory subject in Estonian schools. Meanwhile the ECC argues that while religious studies should not be based on the teachings of a specic denomination and

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

Estonia: ChristianNon-Christian Relations

51

should be ecumenical in nature, a concentration on Christianity is still justied; the current religious situation and the fact that Estonia belongs to the Christian cultural space are good enough reasons to teach Christianity more thoroughly (Seisukohad, 2002). In December 2002 the EELC organised round-table discussions on the teaching of religious studies in Estonian schools. Among the participants were the prime minister, the minister of internal aairs, sta members of the department of religious aairs, representatives of higher education institutions teaching theology and representatives of all Christian and non-Christian religions. The participants reached a common view that religious studies should be based on pluralism, with no religion or worldview forced upon pupils. They also deplored any kind of religious fundamentalism and deemed it necessary to prevent its appearance in society. The participants declared several common positions, including the view that religious studies might be made a marlaua, 2002). A month later, however, compulsory subject in Estonian schools (U the RTRO issued a press release to the eect that announcing a common position on including religious studies among compulsory school subjects was misleading. In practice, this announcement made the whole declaration of common positions pointless. The RTRO stuck rmly to its position that in the current situation the compulsory teaching of religious studies was impossible. Some months after the round-table discussions took place an article was published on the front page of the biggest daily newspaper Postimees in which the author declared that religious studies would soon become a compulsory school subject. The question was the subject of passionate and even aggressive discussion during the next ten weeks. Most articles were critical, sometimes extremely critical, of religious studies. Discussions of the question whether religious studies was an appropriate school subject revealed more general attitudes towards religion as such. The most frequent assertions were that religion was connected with violence and that religion was in conict with science and obstructed scientic development. Many critics attacked the Lutheran Church and other Christian organisations, arguing that Christianity creates hypocrisy and that the churches are trying to increase their membership unfairly through the vehicle of religious studies (Valk, 2007). The question was also discussed in parliament and in the government. Most political parties supported and still support the idea of teaching religious studies on a voluntary basis. In January 2005 the Minister of Education Toivo Maimets came up with the idea of conducting a referendum on the question. A similar referendum conducted in 1923 showed 71.9 per cent in favour of religious studies. The situation remains unchanged. The RTRO has not met for a couple of years, and has not altered its position on religious studies. Currently about 60 schools teach religious studies on a voluntary basis. The proponents of religious studies have in some respects prevailed. Because the issue of religion is so topical, the number of schools teaching the subject has risen considerably. Religious studies are especially popular in secondary schools, where the emphasis is on dierent religions. Conclusion Discussion on religious studies in schools continues in the secular media in Estonia and in this context more and more schools are starting to teach the subject on a voluntary basis. In 2006 a group of MPs produced draft legislation which would have made religious education a compulsory subject in secondary schools, but it was turned down twice by parliament. Since the round-table discussions of 2002, meanwhile, the

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

52

Triin Vakker & Priit Rohtmets

various religions have more or less ceased discussing religious studies and the situation is stable. More general discussions among religions are almost non-existent as well. If problems arise the various religious organisations prefer to turn to the state, because this can lead to tangible results. In this respect, one has to agree with the head of the religious aairs department, Ilmo Au, who emphasises the quiet coexistence of the various religions and the relatively friendly relations among them. There is no discrimination against religious minorities. The main potential cause for concern, however, is widespread prejudice against believers and religions, which underlies a generally negative attitude towards religion in society at large.

Notes

1 The research on which this article is based was supported by the Estonian Science Foundation, grant 6624. 2 Twenty-three per cent answered this question saying that they were unable or unwilling to answer it; 8 per cent did not answer it at all. See Hansen, 2002, pp. 13 14. 3 According to Hansen (2002, p. 13) the percentages of nonreligious in the Nordic countries are: Denmark, 22; Norway, 50; Sweden 56; Finland 34. The percentage of atheists in these countries is between 3 and 6 per cent. In Estonia, according to the 2000 census, the percentage of nonreligious is 71 and the percentage of atheists is 6. 4 For the history of the EELC, see www.eelk.ee/english.php (last accessed 10 December 2007). 5 Active members means those who pay their annual church tax, attend services and take part in other church-related functions. Most of the church members who are not active in this sense are people who joined the church in the late 1980s, when it was extremely popular, or even earlier, when church membership marked a kind of protest against Soviet rule. Even if they do not pay the church tax they are not expelled, because there is neither the will nor the means to do so. 6 For the membership of the Estonian Council of Churches see www.ekn.ee/ index.php?lkliikmed (last accessed 10 December 2007). 7 As its name implies, the House of Taara and Native Religions includes adherents of two faiths. The Taara faith was founded in the 1920s. Like the native religion, it aims to restore the traditional religion of the Estonians which was destroyed after the arrival of Christianity. However, the Taara faith is distinct from the native religion. The latter emphasises an older national heritage; there are many gods but they do not play a central role. Taara was originally the god of the biggest island of Estonia, Saaremaa. The initiators of the Taara faith tried to create a religion which would be close to Estonian identity, but also evolving and contemporary. However, it has not continued as a viable faith and its membership is dwindling. 8 These various terms refer to dierent types of structure. For example, a church has to have an episcopal structure, but a congregation does not.

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

References

EELK (2002) EELK seisukohad religiooniopetuse ku simuses (The EELCs Position on Religious Studies), 15 November, www.eelk.ee/religiooniopetus.html (last accessed 6 March 2007). Eestis (1995) Eestis pole ususo dasid ette na ha (There are no religious wars foreseen in Estonia), Eesti Paevaleht, 2 November, www.epl.ee/artikkel_474.html (last accessed 6 March 2007). Hansen, H. (2002) Luterlased, oigeusklikud ja teised: usuuhendused Eestis 1934 2000 (Lutherans, Orthodox and Others: Religious Organisations in Estonia 1934 2000) (Tallinn, no publisher given).

Estonia: ChristianNon-Christian Relations

53

Kaasik, A. (2003) Siseministeeriumis arutati diskrimineeriva seaduse muutmist (Discussion Meeting Held in Ministry of Internal Aairs Concerning Alteration of Discriminatory Act) (press release from the Estonian House of Taara and Native Religions), 19 December, www.maavald.ee/press.html?rubriik24&id267&oplugu (last accessed 6 March). Kilemit, L. and No mmik, U. (2004) Eesti elanike suhtumisest religiooni (The attitude of the Estonian people towards religion), in L. Altnurme (ed.), Mitut usku Eesti (Multireligious Estonia) (Tartu, Tartu University Press). Linnas, R. (2004) Islam Eestis (Islam in Estonia), in L. Altnurme (ed.), Mitut usku Eesti (Multireligious Estonia) (Tartu, Tartu University Press). Maausust (n.d.) Maausust, www.maavald.ee/maausk.html (last accessed 6 March 2007). Po lenik, A. (2004) Budismist Eestis (Buddhism in Estonia), in L. Altnurme (ed.), Mitut usku Eesti (Multireligious Estonia) (Tartu, Tartu University Press). Presidendile (2002) The Estonian Islamic Congregation, the Estonian Bahai Congregation and the Estonian Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist Congregation, Presidendile, 20 February, www.maavald.ee/koda.html?rubriik36&id137&oplugu (last accessed 6 March 2007). Press release (2002) Estonia Discriminates Non-Christians (press release from the Round Table of Religious Organisations), 4 December, www.maavald.ee/koda.html?rubriik 36&id142&oplugu (last accessed 10 December 2007). Ringvee, R. (2003) Orthodox Churches in Estonia, http://www.einst.ee/culture/index3.html (last accessed 14 September 2007). Seisukohad (2002) The Estonian Council of Churches, Seisukohad religiooniopetuse kusimuses (Position on Religious Studies), 24 October, altered 16 November, www.ekn.ee/ index.php?lktoovaldkonnad&valdkondusuopetus (last accessed 6 March 2007). marlaua religiooniopetus uldhariduskoolides uhisseisukohad (Common marlaua (2002) U U Positions of the Round Table Religious Studies in Secondary Schools), 5 December, www.eelk.ee/religiooniopetus.html (last accessed 6 March 2007). marlaud peab kohustuslikku usuopetust enneaegseks (The Round Table of marlaud (2001) U U Religious Organisations Considers Religous Studies in Estonian Schools Premature) (press release from the Round Table of Religious Organisations), 20 April, www. maavald.ee/ koda.html.?rubriik36&id136&oplugu (last accessed 6 March 2007). marlaud kohustusliku religiooniopetuse vastu (The Round Table of Religious marlaud (2003) U U Organisations Opposes Obligatory Religious Studies in Estonia) (press release from the Round Table of Religious Organisations), 14 January, www.maavald.ee/koda.html? rubriik36&id141&oplugu (last accessed 6 March 2007). henduste U marlaud kavandab konstruktiivset koostood Eesti Vabariigi Usuliste (2002a) Usuliste U Valitsusega (The Round Table of Religious Organisations Plans Constructive Co-operation with the Government of Estonia) (press release from the Round Table of Religious Organisations), 15 November, www.maavald.ee/koda.html?rubriik36&id 138&oplugu (last accessed 6 March 2007). henduste U marlaud taunib usuvabaduse rikkumist Eestis (The Round Usuliste (2002b) Usuliste U Table of Religious Organisations Condemns the Violation of Religous Freedom in Estonia) (press release from the Round Table of Religious Organisations), 29 November, www.maavald.ee/koda.html?rubriik36&id140&oplugu (last accessed 6 March 2007). Usuvabadus (n.d.) Usuvabadus, www.maavald.ee/koda.html?oprubriik&rubriik30 (last accessed 10 December 2007). Valk, P. (2007) Religious education in Estonia, in R. Jackson, S. Miedema, W. Weisse and J.-P. Willaime (eds.), Religion and Education in Europe: Developments, Contexts and Debates (Mu nster, Waxmann).

Downloaded By: [TBTAK EKUAL] At: 13:50 2 September 2009

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Bristol 1st DegreeDocument34 pagesBristol 1st DegreeOmer Tecimer100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Theology of Missions PaperDocument11 pagesTheology of Missions Paperjohnnyrod1952100% (2)

- Collis and Bayer - Initiating The Millennium PDFDocument1 pageCollis and Bayer - Initiating The Millennium PDFBob CollisNo ratings yet

- AH The Greatest Coincidence in HistoryDocument6 pagesAH The Greatest Coincidence in HistoryBCNo ratings yet

- Conditional ForgivenessDocument3 pagesConditional Forgivenesskal6800No ratings yet

- First MassDocument35 pagesFirst MassFarah Jaye Verde Cayayan100% (3)

- The Kingdom of BloodDocument17 pagesThe Kingdom of BloodIsaque Resende100% (1)

- Translation of Monoliths by AH Lyngdoh (Partial)Document1 pageTranslation of Monoliths by AH Lyngdoh (Partial)Roger Manners100% (1)

- Sep 2017Document63 pagesSep 2017Natacia Rimorin-DizonNo ratings yet

- Acts 10 - (4 23-31) - When The Church PraysDocument13 pagesActs 10 - (4 23-31) - When The Church PraysMisaelPeixotoNo ratings yet

- Craig Simonian - On The Baptism of The Holy SpiritDocument13 pagesCraig Simonian - On The Baptism of The Holy SpiritjrcjejjNo ratings yet

- Morgana's Alter Ego - Doc 1Document10 pagesMorgana's Alter Ego - Doc 1matchmaker016No ratings yet

- Epc Leadership Training GuideDocument188 pagesEpc Leadership Training GuideJoseAliceaNo ratings yet

- Dan 11 40 45significance PDFDocument72 pagesDan 11 40 45significance PDFVlad BragaruNo ratings yet

- Frans J. Los - The FranksDocument114 pagesFrans J. Los - The FranksArchiefCRNo ratings yet

- Sda Church Maganjo Pulpit (Platform) Design: Section S - SDocument1 pageSda Church Maganjo Pulpit (Platform) Design: Section S - SYosamuKigongoNo ratings yet

- Semi ArianismDocument4 pagesSemi ArianismJoe MagilNo ratings yet

- Prayer For Newly Ordained Priests: Prayer For The 2018 Year of The Clergy and Consecrated PersonsDocument1 pagePrayer For Newly Ordained Priests: Prayer For The 2018 Year of The Clergy and Consecrated PersonsNestor JrNo ratings yet

- My Life and EthiopiaDocument200 pagesMy Life and EthiopiaEd HowardNo ratings yet

- Advanced/Intermediate DB Rejoice (Sinach)Document2 pagesAdvanced/Intermediate DB Rejoice (Sinach)Tendai MandibatsiraNo ratings yet

- Lion & Serpent: In, Ivxv - Volume 12, Number 1Document40 pagesLion & Serpent: In, Ivxv - Volume 12, Number 1Max anykey100% (1)

- Module 4Document18 pagesModule 4Christian Diki JooeNo ratings yet

- Bernardus Claraevallensis - de Laude Novae Militiae Ad Milites TempliDocument30 pagesBernardus Claraevallensis - de Laude Novae Militiae Ad Milites Templimanlio_peruginiNo ratings yet

- GospelBroadcastingMission 1979 USA PDFDocument22 pagesGospelBroadcastingMission 1979 USA PDFthe missions networkNo ratings yet

- Reinking The Truth About 666Document2 pagesReinking The Truth About 666Chevy ChippyNo ratings yet

- History of The PapacyDocument387 pagesHistory of The PapacyJesus Lives100% (1)

- Holy Rosary GuideDocument30 pagesHoly Rosary GuideFelix Soliva GudelosaoNo ratings yet

- A Concise Catalogue of The European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtDocument112 pagesA Concise Catalogue of The European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtMonica BîldeaNo ratings yet

- SWRB Puritan Hard Drive CategoriesDocument4,538 pagesSWRB Puritan Hard Drive CategorieswdeliasNo ratings yet

- March 2016 EpistleDocument26 pagesMarch 2016 EpistleBradford Congregational ChurchNo ratings yet