Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Innovation: Value For Money (VFM) Is The Term Used To Assess Whether or Not An Organisation Has Obtained

Innovation: Value For Money (VFM) Is The Term Used To Assess Whether or Not An Organisation Has Obtained

Uploaded by

aryanboxer786Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Trump ComplaintDocument41 pagesTrump ComplaintThe Western JournalNo ratings yet

- Nonimmigrant Visa - Confirmation PageDocument2 pagesNonimmigrant Visa - Confirmation Pageislamiccomputers9465No ratings yet

- Child Labour Laws in IndiaDocument22 pagesChild Labour Laws in IndiaJennz MontyNo ratings yet

- The Factories Act of 1948: The Act Prohibits The Employment of Children Below The Age of 14Document5 pagesThe Factories Act of 1948: The Act Prohibits The Employment of Children Below The Age of 14SanctaTiffanyNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in India: Navigation SearchDocument10 pagesChild Labour in India: Navigation SearchVinod SinghNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in India PDFDocument21 pagesChild Labour in India PDFKs ThanyaaNo ratings yet

- DefinitionDocument5 pagesDefinitionSumit SinghNo ratings yet

- Businesss Law AssignmentDocument8 pagesBusinesss Law Assignmentjashish4No ratings yet

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument9 pagesChild Labour in IndiaVijay ChanderNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in Indi1Document12 pagesChild Labour in Indi1Gaurav JaiswalNo ratings yet

- India: Child LabourDocument9 pagesIndia: Child LabourtusharNo ratings yet

- Introduction On Child LabourDocument22 pagesIntroduction On Child LabourADITYA YADAV100% (1)

- Labour Law 1Document17 pagesLabour Law 1AnantHimanshuEkkaNo ratings yet

- Is It Possible To Justify Child Labour Under Any Circumstances?Document8 pagesIs It Possible To Justify Child Labour Under Any Circumstances?TeerthaNo ratings yet

- Labour Law ProjectDocument17 pagesLabour Law ProjectKunal Singh100% (1)

- Labour Law: Take Home AssignmentDocument9 pagesLabour Law: Take Home AssignmentNilesh SinhaNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Eradication of Child Labour in India: Khushi MehtaDocument11 pagesStrategies For Eradication of Child Labour in India: Khushi Mehtayogeshgoriya777No ratings yet

- Child Labour TheoryDocument4 pagesChild Labour Theorysanjanavijayan.975No ratings yet

- Child Labour AssignmentDocument6 pagesChild Labour AssignmentYazhlini TholgappianNo ratings yet

- Right Versus Needs: Scrutiny of Right To Education Vis-À-Vis Child Labour in IndiaDocument12 pagesRight Versus Needs: Scrutiny of Right To Education Vis-À-Vis Child Labour in IndiaShah MuneebNo ratings yet

- 3 Fdef 5Document6 pages3 Fdef 5Satyarth SinghNo ratings yet

- Child LabourDocument1 pageChild LabourNaMan SeThiNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in India Babu - MT: Definition of Child LaborDocument4 pagesChild Labour in India Babu - MT: Definition of Child LaborBabcho MtNo ratings yet

- Chiildlabour With DataDocument31 pagesChiildlabour With DataprateekNo ratings yet

- Legal Principals and Normative Realities - A Study On Childerns Rights and Child Labour in IndiaDocument15 pagesLegal Principals and Normative Realities - A Study On Childerns Rights and Child Labour in IndiaMouneeshNo ratings yet

- Child Labor in IndiaDocument13 pagesChild Labor in IndiaRasha YatmeenNo ratings yet

- PHD Revised 28 OctDocument36 pagesPHD Revised 28 OctNaveen KumarNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument8 pagesSynopsisMohan Savade100% (1)

- Law and Poverty FINALDocument17 pagesLaw and Poverty FINALNIKHILA VEMURINo ratings yet

- Made by - MD .Zainul Haque: I Want To StudyDocument16 pagesMade by - MD .Zainul Haque: I Want To Studymd.zainul haqueNo ratings yet

- Project Title: Child Is Meant To Learn Not To EarnDocument17 pagesProject Title: Child Is Meant To Learn Not To EarnSAI DEEP GADANo ratings yet

- Executive Summary and ReportDocument33 pagesExecutive Summary and Reportpriyanka_bala_1No ratings yet

- Research Article On Labour Laws: Title: Child Labour - Just A Paper Tiger?Document16 pagesResearch Article On Labour Laws: Title: Child Labour - Just A Paper Tiger?Kishita GuptaNo ratings yet

- English Project. Child Labour.Document7 pagesEnglish Project. Child Labour.deepaknayakipsNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Child Labour in IndiaDocument8 pagesDissertation On Child Labour in IndiaWhereToBuyCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Child Labour LawsDocument41 pagesChild Labour LawsAastha VijNo ratings yet

- Child Labour The Evil Eye For IndiaDocument4 pagesChild Labour The Evil Eye For IndiaAstha AryaNo ratings yet

- Child Labour MUN (Position Paper)Document2 pagesChild Labour MUN (Position Paper)Alex GodoNo ratings yet

- Right To Education and Child LabourDocument11 pagesRight To Education and Child LabourSourabh YadavNo ratings yet

- An EssayDocument3 pagesAn EssayLinggi TiluNo ratings yet

- Child Labour and Forced Labour in IndiaDocument4 pagesChild Labour and Forced Labour in IndiaTrupti JadhavNo ratings yet

- Child Labour PDFDocument17 pagesChild Labour PDFSakshi AnandNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument12 pagesChild Labour in IndiaDUKI BANANo ratings yet

- Child LabourDocument10 pagesChild LabourtheaakimynameNo ratings yet

- 4 Issue 3 Intl JLMGMT Human 230Document8 pages4 Issue 3 Intl JLMGMT Human 230Atul KishorNo ratings yet

- LLM Dissertation On Child Labour in IndiaDocument6 pagesLLM Dissertation On Child Labour in IndiaBuyingCollegePapersOnlineAnchorage100% (1)

- Master Thesis On Child Labour in IndiaDocument4 pagesMaster Thesis On Child Labour in Indiakellydoepkefortwayne100% (2)

- Assignment PDFDocument30 pagesAssignment PDFobaidshamsanNo ratings yet

- A Project Focused On Child LabourDocument9 pagesA Project Focused On Child LabourMaru Perez AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Child Labour IndiaDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Child Labour Indiatug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Child Labor in India Research PaperDocument7 pagesChild Labor in India Research Paperaflbrozzi100% (1)

- Article On Child LabourDocument4 pagesArticle On Child LabourRavi ThakurNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Child Labour in IndiaDocument8 pagesResearch Papers On Child Labour in Indiagw1wayrw100% (1)

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument20 pagesChild Labour in IndiaChintan PatelNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Child Labour in IndiaDocument12 pagesCritical Analysis of Child Labour in Indiakomalvjain21No ratings yet

- The Hindu Editorial DiscussionDocument36 pagesThe Hindu Editorial DiscussionAnamika AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument7 pagesChild Labour in IndiaSerena_Fernand_622No ratings yet

- IndiaDocument3 pagesIndiasavage boysNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and Education in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteFrom EverandCOVID-19 and Education in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteNo ratings yet

- The Billion Minds: India's Quest to Train a Billion Workforce (English Edition)From EverandThe Billion Minds: India's Quest to Train a Billion Workforce (English Edition)No ratings yet

- Two Year Diploma Cource In: Msme-Technology Development CenterDocument1 pageTwo Year Diploma Cource In: Msme-Technology Development Centeraryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Mba105 - Managerial EconomicsDocument2 pagesMba105 - Managerial Economicsaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Syllabus For Testing of Footwear Materials & Complete FootwearDocument4 pagesSyllabus For Testing of Footwear Materials & Complete Footweararyanboxer786No ratings yet

- What Is A TextureDocument3 pagesWhat Is A Texturearyanboxer786No ratings yet

- Candidates For Placenment: S.No. Name BatchDocument4 pagesCandidates For Placenment: S.No. Name Batcharyanboxer786No ratings yet

- Name Dipartment Mobile Raw MaterialDocument2 pagesName Dipartment Mobile Raw Materialaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Purpose of SkiviingDocument2 pagesPurpose of Skiviingaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Legal AspectsDocument9 pagesLegal Aspectsaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- LASTING TameemDocument40 pagesLASTING Tameemaryanboxer786100% (1)

- U Lip MutualDocument87 pagesU Lip Mutualaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Lasting FAQDocument4 pagesLasting FAQaryanboxer786100% (1)

- CFTIDocument1 pageCFTIaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Management Information SystemDocument7 pagesManagement Information Systemaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- AbhishekDocument2 pagesAbhishekaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- CFTIDocument1 pageCFTIaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Production and Operations ManagementDocument9 pagesProduction and Operations Managementaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Quality QDocument3 pagesQuality Qaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Financial Management: Liquidity DecisionsDocument10 pagesFinancial Management: Liquidity Decisionsaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Ayodha PMDocument7 pagesAyodha PMaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- MB0038 - Management Process and Organizational BehaviorDocument9 pagesMB0038 - Management Process and Organizational Behavioraryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Development & Business PlanDocument67 pagesEntrepreneurship Development & Business Planaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Part-A 2 X 10 20Document3 pagesPart-A 2 X 10 20aryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Katherine Jackson V AEG Live Transcripts of Debbie Rowe (MJ's Ex Wife-Dr Klein's Ex Nurse) August 14th 2013Document94 pagesKatherine Jackson V AEG Live Transcripts of Debbie Rowe (MJ's Ex Wife-Dr Klein's Ex Nurse) August 14th 2013TeamMichael100% (5)

- Memorandum and Articles of Association of Wipro LimitedDocument321 pagesMemorandum and Articles of Association of Wipro LimitedMeghana S BIMSNo ratings yet

- Bannari Amman Sugars LTD Vs Commercial Tax Officer and OthersDocument15 pagesBannari Amman Sugars LTD Vs Commercial Tax Officer and Othersvrajamabl100% (2)

- Ang Mga Kaanib Sa Iglesia NG Dios Kay Kristo Hesus v. Iglesia NG Dios Kay Cristo JesusDocument8 pagesAng Mga Kaanib Sa Iglesia NG Dios Kay Kristo Hesus v. Iglesia NG Dios Kay Cristo JesusCassie GacottNo ratings yet

- 22 Flancia Vs Court of Appeals - Digest (Kadz)Document3 pages22 Flancia Vs Court of Appeals - Digest (Kadz)breeH20100% (2)

- Quiet TitleDocument45 pagesQuiet TitleGregg BarnesNo ratings yet

- Persons Finals SecondDocument13 pagesPersons Finals SecondKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Military Resistance 9F 16: "A World of Rage"Document29 pagesMilitary Resistance 9F 16: "A World of Rage"paola pisiNo ratings yet

- 13 Businessday Information Systems and Services, Inc. vs. NLRCDocument4 pages13 Businessday Information Systems and Services, Inc. vs. NLRCjudyrane0% (1)

- Lucio Dimayuga V Antonio DimayugaDocument1 pageLucio Dimayuga V Antonio DimayugaLaura R. Prado-LopezNo ratings yet

- Dumlao V Quality PlasticsDocument2 pagesDumlao V Quality PlasticsAngelo LopezNo ratings yet

- RPD Daily Incident Report 6/22/23Document5 pagesRPD Daily Incident Report 6/22/23inforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Complete Your Enrolment Process Siddesh PPDocument6 pagesComplete Your Enrolment Process Siddesh PPSiddesh PingaleNo ratings yet

- Dalton v. FGR RealtyDocument2 pagesDalton v. FGR RealtyEcnerolAicnelavNo ratings yet

- Form 1-Scc: (Ang Bawat Panig Ay Ang Mga Sumusunod)Document9 pagesForm 1-Scc: (Ang Bawat Panig Ay Ang Mga Sumusunod)Sandy CelineNo ratings yet

- FINAL WillsSuccession BARQAs 199-2016Document35 pagesFINAL WillsSuccession BARQAs 199-2016lleiryc7No ratings yet

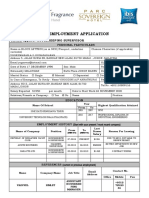

- Employment Application: ConfidentialDocument3 pagesEmployment Application: ConfidentialVinoodini AnnathuraiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 - International TaxationDocument11 pagesChapter 11 - International TaxationlinaelinaaaNo ratings yet

- Full Download Research Methods Exploring The Social World Canadian Canadian 1st Edition Diane Symbaluk Test BankDocument36 pagesFull Download Research Methods Exploring The Social World Canadian Canadian 1st Edition Diane Symbaluk Test BankbeinskelianpNo ratings yet

- ROP1Document2 pagesROP1Edwin ShaoNo ratings yet

- Filipino LanguageDocument3 pagesFilipino LanguageSanja PesicNo ratings yet

- HONOUR KILLING FinalDocument22 pagesHONOUR KILLING FinalRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- Get The Black Fox Brianna Hale (Hale PDF Full ChapterDocument9 pagesGet The Black Fox Brianna Hale (Hale PDF Full Chaptercobinzanuar100% (6)

- Rule 132 Authentication and Proof of Docments CasesDocument90 pagesRule 132 Authentication and Proof of Docments CasesHyuga NejiNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 28 Aug 2021Document23 pagesAdobe Scan 28 Aug 2021Merlin KNo ratings yet

- Bhagwati Prasad Pawan Kumar Vs Union of IndiaDocument16 pagesBhagwati Prasad Pawan Kumar Vs Union of IndiaSamarth UdasinNo ratings yet

- Indian Evidence Act Renaissance Law College Notes - PDF - Evidence (Law) - EvidenceDocument78 pagesIndian Evidence Act Renaissance Law College Notes - PDF - Evidence (Law) - EvidenceJagriti SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Int CCPR Css Bra 52858 eDocument23 pagesInt CCPR Css Bra 52858 eRodrigo DeodatoNo ratings yet

Innovation: Value For Money (VFM) Is The Term Used To Assess Whether or Not An Organisation Has Obtained

Innovation: Value For Money (VFM) Is The Term Used To Assess Whether or Not An Organisation Has Obtained

Uploaded by

aryanboxer786Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Innovation: Value For Money (VFM) Is The Term Used To Assess Whether or Not An Organisation Has Obtained

Innovation: Value For Money (VFM) Is The Term Used To Assess Whether or Not An Organisation Has Obtained

Uploaded by

aryanboxer786Copyright:

Available Formats

Innovation The process of translating an idea or invention into a good or service that creates value or for which customers

will pay. To be called an innovation, an idea must be replicable at an economical cost and must satisfy a specific need. Innovation involves deliberate application of information, imagination and initiative in deriving greater or different values from resources, and includes all processes by which new ideas are generated and converted into useful products. In business, innovation often results when ideas are applied by the company in order to further satisfy the needs and expectations of the customers. In a social context, innovation helps create new methods for alliance creation, joint venturing, flexible work hours, and creation of buyers' purchasing power. Innovations are divided into two broad categories: (1) Evolutionary innovations (continuous or dynamic evolutionary innovation) that are brought about by many incremental advances in technology or processes and (2) revolutionary innovations (also called discontinuous innovations) which are often disruptive and new. Innovation is synonymous with risk-taking and organizations that create revolutionary products or technologies take on the greatest risk because they create new markets. Imitators take less risk because they will start with an innovator's product and take a more effective approach. Examples are IBM with its PC against Apple Computer, Compaq with its cheaper PC's against IBM, and Dell with its still-cheaper clones against Compaq. Value for Money (VfM) is the term used to assess whether or not an organisation has obtained the maximum benefit from the goods and services it acquires and/ or provides, within the resources available to it. It not only measures the cost of goods and services, but also takes account of the mix of quality, cost, resource use, fitness for purpose, timeliness and convenience to judge whether or not, when taken together, they constitute good value. Achieving VfM may be described in terms of the 'three Es' - economy, efficiency and effectiveness.

A government imposed restriction on. the free international exchange of goods or services 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Trade barriers are generally classified as import policies reflected in tariffs and other import charges, quotas, import licensing, customs practices, standards, testing, labeling, and various types of certification direct procurement by government, subsidies for local exporters, lack of copyright protection, restrictions on franchising, licensing, technology transfer, restrictions on foreign direct investment, etc.

Child labour in India is the practice where children engage in economic activity, on part or full-time basis. The practice deprives children of their childhood, and is harmful to their physical and mental development. Poverty, lack of good schools and growth of informal economy are considered as the important causes of child labour in India.[1][2] b The 2001 national census of India estimated the total number of child labour, aged 5 14, to be at 12.6 million.[3] Child labor problem is not unique to India; worldwide, about 217 million children work, many full-time.[4] In 2001, out of a 12.6 million, about 12 million children in India were in a hazardous job.[5]UNICEF estimates that India with its larger population, has the highest number of labourers in the world under 14 years of age, while sub-saharan African countries have the highest percentage of children who are deployed as child labour.[6][7][8] International Labour Organization estimates that agriculture at 60 percent is the largest employer of child labor in India, [9] while United Nation's Food and Agriculture Organization estimates 70 percent of child labour is deployed in agriculture and related activities.[10] Outside of agriculture, child labour is observed in almost all informal sectors of the Indian economy

Child labour laws in India

Section 12 of India's Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986 requires prominent display of 'child labor is prohibited' signs in many industries and construction sites in local language and English. Above a sign at a construction site in Bangalore.

After its independence from colonial rule, India has passed a number of constitutional protections and laws on child labor. The Constitution of India in the Fundamental Rights and the Directive Principles of State Policy prohibits child labor below the age of 14 years in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment (Article 24). The constitution also envisioned that India shall, by 1960, provide infrastructure and resources for free and compulsory education to all children of the age six to 14 years. (Article 21-A and Article 45).[20][21] India is a federal form of government, and child labour is a matter on which both the central government and state governments can legislate, and have. The major national legislative developments include the following:[22]

The Factories Act of 1948: The Act prohibits the employment of children below the age of 14 years in any factory. The law also placed rules on who, when and how long can pre-adults aged 1518 years be employed in any factory. The Mines Act of 1952: The Act prohibits the employment of children below 18 years of age in a mine. The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986: The Act prohibits the employment of children below the age of 14 years in hazardous occupations identified in a list by the law. The list was expanded in 2006, and again in 2008. The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) of Children Act of 2000: This law made it a crime, punishable with a prison term, for anyone to procure or employ a child in any hazardous employment or in bondage. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act of 2009 : The law mandates free and compulsory education to all children aged 6 to 14 years. This legislation also mandated that 25 percent of seats in every private school must be allocated for children from disadvantaged groups and physically challenged children. India formulated a National Policy on Child Labour in 1987. This Policy seeks to adopt a gradual & sequential approach with a focus on rehabilitation of children working in hazardous occupations. It envisioned strict enforcement of Indian laws on child labor combined with development programs to address the root causes of child labor such as poverty. In 1988, this led to the National Child Labour Project (NCLP) initiative. This legal and development initiative continues, with a current central government funding of 602 crores, targeted solely to eliminate child labor in India. [23] Despite these efforts, child labor remains a major challenge for India

Causes

Children working in a rural area of colonial India, around an oil press, in 1916.

For much of human history and across different cultures, children less than 17 years old have contributed to family welfare in a variety of ways. UNICEF suggests that poverty encourages child labour. The report also notes that in rural and impoverished parts of developing and undeveloped parts of the world, children have no real and meaningful alternative. Schools and teachers are

unavailable. Child labour is the unnatural result.[24] A BBC report, similarly, concludes poverty and inadequate public education infrastructure are some of the causes of child labour in India. [25] Between boys and girls, UNICEF finds girls are two times more likely to be out of school and working in a domestic role. Parents with limited resources, claims UNICEF, have to choose whose school costs and fees they can afford when a school is available. Educating girls tends to be a lower priority across the world, including India. Girls are also harassed or bullied at schools, sidelined by prejudice or poor curricula, according to UNICEF. Solely by virtue of their gender, therefore, many girls are kept from school or drop out, then provide child labour.[24] International Labor Organization (ILO) suggests poverty is the greatest single force driving children into the workplace.[1] Income from a child's work is felt to be crucial for his/her own survival or for that of the household. For some families, income from their children's labour is between 25 to 40% of the household income. According to a 2008 study by ILO,[1] among the most important factors driving children to harmful labour is the lack of availability and quality of schooling. Many communities, particularly rural areas do not possess adequate school facilities. Even when schools are sometimes available, they are too far away, difficult to reach, unaffordable or the quality of education is so poor that parents wonder if going to school is really worth it. In government-run primary schools, even when children show up, government-paid teachers do not show up 25% of the time.[26][27][28] The 2008 ILO study suggests that illiteracy resulting from a child going to work, rather than a quality primary and secondary school, limits the child's ability to get a basic educational grounding which would in normal situations enable them to acquire skills and to improve their prospects for a decent adult working life An albeit older report published by UNICEF outlines the issues summarized by the ILO report. The UNICEF report claimed that while 90% of child labour in India is in its rural areas, the availability and quality of schools is decrepit; in rural areas of India, claims the old UNICEF report, about 50% of government funded primary schools that exist do not have a building, 40% lack a blackboard, few have books, and 97% of funds for these publicly funded school have been budgeted by the government as salaries for the teacher and administrators. A 2012 Wall Street Journal article reports while the enrollment in India's school has dramatically increased in recent years to over 96% of all children in the 6-14 year age group, the infrastructure in schools, aimed in part to reduce child labour, remains poor - over 81,000 schools do not have a blackboard and about 42,000 government schools operate without a building with make shift arrangements during monsoons and inclement weather. Biggeri and Mehrotra have studied the macroeconomic factors that encourage child labour. They focus their study on five Asian nations including India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Thailand and Philippines. They suggest that child labour is a serious problem in all five, but it is not a new problem. Macroeconomic causes encouraged widespread child labour across the world, over most of human history. They suggest that the causes for child labour include both the demand and the supply side. While poverty and unavailability of good schools explain the child labour supply side, they suggest that the growth of low paying informal economy rather than higher paying formal economy - called organized economy in India - is amongst the causes of the demand side. India has rigid labour laws and numerous regulations that prevent growth of organized sector where work protections are easier to monitor, and work more productive and higher paying. The unintended effect of Indian complex labour laws is the

work has shifted to the unorganized, informal sector. As a result, after unorganized agriculture sector which employs 60% of child labor, it is the unorganized trade, unorganized assembly and unorganized retail work that is the largest employer of child labour. If macroeconomic factors and laws prevent growth of formal sector, the family owned informal sector grows, deploying low cost, easy to hire, easy to dismiss labour in form of child labour. Even in situations where children are going to school, claim Biggeri and Mehrotra, children engage in routine after-school home-based manufacturing and economic activity. Other scholars too suggest that inflexibility and structure of India's labor market, size of informal economy, inability of industries to scale up and lack of modern manufacturing technologies are major macroeconomic factors affecting demand and acceptability of child labour. Cigno et al. suggest the government planned and implemented land redistribution programs in India, where poor families were given small plots of land with the idea of enabling economic independence, have had the unintended effect of increased child labour. They find that smallholder plots of land are labor-intensively farmed since small plots cannot productively afford expensive farming equipment. In these cases, a means to increase output from the small plot has been to apply more labour, including child labou

DEREGULATION Deregulation is an act by which the government regulation of a particular industry is reduced or eliminated in order to create and foster a more efficient marketplace. Deregulation is usually enacted to weaken government influence and forge greater competition. By this token, deregulation also creates an economic environment favorable to upstart companies that were unable to enter the industry prior to the passing of deregulation. It is also widely held that deregulation often serves as a catalyst for increased innovation and mergers among weaker competitors. Deregulation is often driven by lobbyists and lobbying groups that represent various industries and business interests. Industries that have undergone deregulation include communications, banking, securities, transportation, as well as power and utility. Although deregulation might purge government influence all together, some government oversight usually remains.

You might also like

- Trump ComplaintDocument41 pagesTrump ComplaintThe Western JournalNo ratings yet

- Nonimmigrant Visa - Confirmation PageDocument2 pagesNonimmigrant Visa - Confirmation Pageislamiccomputers9465No ratings yet

- Child Labour Laws in IndiaDocument22 pagesChild Labour Laws in IndiaJennz MontyNo ratings yet

- The Factories Act of 1948: The Act Prohibits The Employment of Children Below The Age of 14Document5 pagesThe Factories Act of 1948: The Act Prohibits The Employment of Children Below The Age of 14SanctaTiffanyNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in India: Navigation SearchDocument10 pagesChild Labour in India: Navigation SearchVinod SinghNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in India PDFDocument21 pagesChild Labour in India PDFKs ThanyaaNo ratings yet

- DefinitionDocument5 pagesDefinitionSumit SinghNo ratings yet

- Businesss Law AssignmentDocument8 pagesBusinesss Law Assignmentjashish4No ratings yet

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument9 pagesChild Labour in IndiaVijay ChanderNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in Indi1Document12 pagesChild Labour in Indi1Gaurav JaiswalNo ratings yet

- India: Child LabourDocument9 pagesIndia: Child LabourtusharNo ratings yet

- Introduction On Child LabourDocument22 pagesIntroduction On Child LabourADITYA YADAV100% (1)

- Labour Law 1Document17 pagesLabour Law 1AnantHimanshuEkkaNo ratings yet

- Is It Possible To Justify Child Labour Under Any Circumstances?Document8 pagesIs It Possible To Justify Child Labour Under Any Circumstances?TeerthaNo ratings yet

- Labour Law ProjectDocument17 pagesLabour Law ProjectKunal Singh100% (1)

- Labour Law: Take Home AssignmentDocument9 pagesLabour Law: Take Home AssignmentNilesh SinhaNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Eradication of Child Labour in India: Khushi MehtaDocument11 pagesStrategies For Eradication of Child Labour in India: Khushi Mehtayogeshgoriya777No ratings yet

- Child Labour TheoryDocument4 pagesChild Labour Theorysanjanavijayan.975No ratings yet

- Child Labour AssignmentDocument6 pagesChild Labour AssignmentYazhlini TholgappianNo ratings yet

- Right Versus Needs: Scrutiny of Right To Education Vis-À-Vis Child Labour in IndiaDocument12 pagesRight Versus Needs: Scrutiny of Right To Education Vis-À-Vis Child Labour in IndiaShah MuneebNo ratings yet

- 3 Fdef 5Document6 pages3 Fdef 5Satyarth SinghNo ratings yet

- Child LabourDocument1 pageChild LabourNaMan SeThiNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in India Babu - MT: Definition of Child LaborDocument4 pagesChild Labour in India Babu - MT: Definition of Child LaborBabcho MtNo ratings yet

- Chiildlabour With DataDocument31 pagesChiildlabour With DataprateekNo ratings yet

- Legal Principals and Normative Realities - A Study On Childerns Rights and Child Labour in IndiaDocument15 pagesLegal Principals and Normative Realities - A Study On Childerns Rights and Child Labour in IndiaMouneeshNo ratings yet

- Child Labor in IndiaDocument13 pagesChild Labor in IndiaRasha YatmeenNo ratings yet

- PHD Revised 28 OctDocument36 pagesPHD Revised 28 OctNaveen KumarNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument8 pagesSynopsisMohan Savade100% (1)

- Law and Poverty FINALDocument17 pagesLaw and Poverty FINALNIKHILA VEMURINo ratings yet

- Made by - MD .Zainul Haque: I Want To StudyDocument16 pagesMade by - MD .Zainul Haque: I Want To Studymd.zainul haqueNo ratings yet

- Project Title: Child Is Meant To Learn Not To EarnDocument17 pagesProject Title: Child Is Meant To Learn Not To EarnSAI DEEP GADANo ratings yet

- Executive Summary and ReportDocument33 pagesExecutive Summary and Reportpriyanka_bala_1No ratings yet

- Research Article On Labour Laws: Title: Child Labour - Just A Paper Tiger?Document16 pagesResearch Article On Labour Laws: Title: Child Labour - Just A Paper Tiger?Kishita GuptaNo ratings yet

- English Project. Child Labour.Document7 pagesEnglish Project. Child Labour.deepaknayakipsNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Child Labour in IndiaDocument8 pagesDissertation On Child Labour in IndiaWhereToBuyCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Child Labour LawsDocument41 pagesChild Labour LawsAastha VijNo ratings yet

- Child Labour The Evil Eye For IndiaDocument4 pagesChild Labour The Evil Eye For IndiaAstha AryaNo ratings yet

- Child Labour MUN (Position Paper)Document2 pagesChild Labour MUN (Position Paper)Alex GodoNo ratings yet

- Right To Education and Child LabourDocument11 pagesRight To Education and Child LabourSourabh YadavNo ratings yet

- An EssayDocument3 pagesAn EssayLinggi TiluNo ratings yet

- Child Labour and Forced Labour in IndiaDocument4 pagesChild Labour and Forced Labour in IndiaTrupti JadhavNo ratings yet

- Child Labour PDFDocument17 pagesChild Labour PDFSakshi AnandNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument12 pagesChild Labour in IndiaDUKI BANANo ratings yet

- Child LabourDocument10 pagesChild LabourtheaakimynameNo ratings yet

- 4 Issue 3 Intl JLMGMT Human 230Document8 pages4 Issue 3 Intl JLMGMT Human 230Atul KishorNo ratings yet

- LLM Dissertation On Child Labour in IndiaDocument6 pagesLLM Dissertation On Child Labour in IndiaBuyingCollegePapersOnlineAnchorage100% (1)

- Master Thesis On Child Labour in IndiaDocument4 pagesMaster Thesis On Child Labour in Indiakellydoepkefortwayne100% (2)

- Assignment PDFDocument30 pagesAssignment PDFobaidshamsanNo ratings yet

- A Project Focused On Child LabourDocument9 pagesA Project Focused On Child LabourMaru Perez AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Child Labour IndiaDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Child Labour Indiatug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Child Labor in India Research PaperDocument7 pagesChild Labor in India Research Paperaflbrozzi100% (1)

- Article On Child LabourDocument4 pagesArticle On Child LabourRavi ThakurNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Child Labour in IndiaDocument8 pagesResearch Papers On Child Labour in Indiagw1wayrw100% (1)

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument20 pagesChild Labour in IndiaChintan PatelNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Child Labour in IndiaDocument12 pagesCritical Analysis of Child Labour in Indiakomalvjain21No ratings yet

- The Hindu Editorial DiscussionDocument36 pagesThe Hindu Editorial DiscussionAnamika AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Child Labour in IndiaDocument7 pagesChild Labour in IndiaSerena_Fernand_622No ratings yet

- IndiaDocument3 pagesIndiasavage boysNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and Education in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteFrom EverandCOVID-19 and Education in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteNo ratings yet

- The Billion Minds: India's Quest to Train a Billion Workforce (English Edition)From EverandThe Billion Minds: India's Quest to Train a Billion Workforce (English Edition)No ratings yet

- Two Year Diploma Cource In: Msme-Technology Development CenterDocument1 pageTwo Year Diploma Cource In: Msme-Technology Development Centeraryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Mba105 - Managerial EconomicsDocument2 pagesMba105 - Managerial Economicsaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Syllabus For Testing of Footwear Materials & Complete FootwearDocument4 pagesSyllabus For Testing of Footwear Materials & Complete Footweararyanboxer786No ratings yet

- What Is A TextureDocument3 pagesWhat Is A Texturearyanboxer786No ratings yet

- Candidates For Placenment: S.No. Name BatchDocument4 pagesCandidates For Placenment: S.No. Name Batcharyanboxer786No ratings yet

- Name Dipartment Mobile Raw MaterialDocument2 pagesName Dipartment Mobile Raw Materialaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Purpose of SkiviingDocument2 pagesPurpose of Skiviingaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Legal AspectsDocument9 pagesLegal Aspectsaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- LASTING TameemDocument40 pagesLASTING Tameemaryanboxer786100% (1)

- U Lip MutualDocument87 pagesU Lip Mutualaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Lasting FAQDocument4 pagesLasting FAQaryanboxer786100% (1)

- CFTIDocument1 pageCFTIaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Management Information SystemDocument7 pagesManagement Information Systemaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- AbhishekDocument2 pagesAbhishekaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- CFTIDocument1 pageCFTIaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Production and Operations ManagementDocument9 pagesProduction and Operations Managementaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Quality QDocument3 pagesQuality Qaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Financial Management: Liquidity DecisionsDocument10 pagesFinancial Management: Liquidity Decisionsaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Ayodha PMDocument7 pagesAyodha PMaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- MB0038 - Management Process and Organizational BehaviorDocument9 pagesMB0038 - Management Process and Organizational Behavioraryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Development & Business PlanDocument67 pagesEntrepreneurship Development & Business Planaryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Part-A 2 X 10 20Document3 pagesPart-A 2 X 10 20aryanboxer786No ratings yet

- Katherine Jackson V AEG Live Transcripts of Debbie Rowe (MJ's Ex Wife-Dr Klein's Ex Nurse) August 14th 2013Document94 pagesKatherine Jackson V AEG Live Transcripts of Debbie Rowe (MJ's Ex Wife-Dr Klein's Ex Nurse) August 14th 2013TeamMichael100% (5)

- Memorandum and Articles of Association of Wipro LimitedDocument321 pagesMemorandum and Articles of Association of Wipro LimitedMeghana S BIMSNo ratings yet

- Bannari Amman Sugars LTD Vs Commercial Tax Officer and OthersDocument15 pagesBannari Amman Sugars LTD Vs Commercial Tax Officer and Othersvrajamabl100% (2)

- Ang Mga Kaanib Sa Iglesia NG Dios Kay Kristo Hesus v. Iglesia NG Dios Kay Cristo JesusDocument8 pagesAng Mga Kaanib Sa Iglesia NG Dios Kay Kristo Hesus v. Iglesia NG Dios Kay Cristo JesusCassie GacottNo ratings yet

- 22 Flancia Vs Court of Appeals - Digest (Kadz)Document3 pages22 Flancia Vs Court of Appeals - Digest (Kadz)breeH20100% (2)

- Quiet TitleDocument45 pagesQuiet TitleGregg BarnesNo ratings yet

- Persons Finals SecondDocument13 pagesPersons Finals SecondKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Military Resistance 9F 16: "A World of Rage"Document29 pagesMilitary Resistance 9F 16: "A World of Rage"paola pisiNo ratings yet

- 13 Businessday Information Systems and Services, Inc. vs. NLRCDocument4 pages13 Businessday Information Systems and Services, Inc. vs. NLRCjudyrane0% (1)

- Lucio Dimayuga V Antonio DimayugaDocument1 pageLucio Dimayuga V Antonio DimayugaLaura R. Prado-LopezNo ratings yet

- Dumlao V Quality PlasticsDocument2 pagesDumlao V Quality PlasticsAngelo LopezNo ratings yet

- RPD Daily Incident Report 6/22/23Document5 pagesRPD Daily Incident Report 6/22/23inforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Complete Your Enrolment Process Siddesh PPDocument6 pagesComplete Your Enrolment Process Siddesh PPSiddesh PingaleNo ratings yet

- Dalton v. FGR RealtyDocument2 pagesDalton v. FGR RealtyEcnerolAicnelavNo ratings yet

- Form 1-Scc: (Ang Bawat Panig Ay Ang Mga Sumusunod)Document9 pagesForm 1-Scc: (Ang Bawat Panig Ay Ang Mga Sumusunod)Sandy CelineNo ratings yet

- FINAL WillsSuccession BARQAs 199-2016Document35 pagesFINAL WillsSuccession BARQAs 199-2016lleiryc7No ratings yet

- Employment Application: ConfidentialDocument3 pagesEmployment Application: ConfidentialVinoodini AnnathuraiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 - International TaxationDocument11 pagesChapter 11 - International TaxationlinaelinaaaNo ratings yet

- Full Download Research Methods Exploring The Social World Canadian Canadian 1st Edition Diane Symbaluk Test BankDocument36 pagesFull Download Research Methods Exploring The Social World Canadian Canadian 1st Edition Diane Symbaluk Test BankbeinskelianpNo ratings yet

- ROP1Document2 pagesROP1Edwin ShaoNo ratings yet

- Filipino LanguageDocument3 pagesFilipino LanguageSanja PesicNo ratings yet

- HONOUR KILLING FinalDocument22 pagesHONOUR KILLING FinalRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- Get The Black Fox Brianna Hale (Hale PDF Full ChapterDocument9 pagesGet The Black Fox Brianna Hale (Hale PDF Full Chaptercobinzanuar100% (6)

- Rule 132 Authentication and Proof of Docments CasesDocument90 pagesRule 132 Authentication and Proof of Docments CasesHyuga NejiNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 28 Aug 2021Document23 pagesAdobe Scan 28 Aug 2021Merlin KNo ratings yet

- Bhagwati Prasad Pawan Kumar Vs Union of IndiaDocument16 pagesBhagwati Prasad Pawan Kumar Vs Union of IndiaSamarth UdasinNo ratings yet

- Indian Evidence Act Renaissance Law College Notes - PDF - Evidence (Law) - EvidenceDocument78 pagesIndian Evidence Act Renaissance Law College Notes - PDF - Evidence (Law) - EvidenceJagriti SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Int CCPR Css Bra 52858 eDocument23 pagesInt CCPR Css Bra 52858 eRodrigo DeodatoNo ratings yet