Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IV 2 Employment Stats On Female and Males 2012

IV 2 Employment Stats On Female and Males 2012

Uploaded by

freak009Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IV 2 Employment Stats On Female and Males 2012

IV 2 Employment Stats On Female and Males 2012

Uploaded by

freak009Copyright:

Available Formats

Facts & Figures

Employment of female and male graduates of US veterinary medical colleges, 2012

Mean starting salary among respondents who accepted full-time positions was $52,255 for males and $43,673 for females. When salaries for positions in advanced education were excluded, the mean full-time salary increased to $69,405 for males and $63,844 for females. Mean educational debt among the 89.2% of respondents who reported debt was $147 ,518 for males and $152,853 for females. Mean eductional debt for all respondents was $129,439 (median, $133,000) for males and $137 ,079 (median, $142,224) for females.

n cooperation with the 28 US schools and colleges of veterinary medicine, the AVMA conducted its annual survey of fourth-year veterinary medical students in the spring of 2012 (Appendix). Surveys were sent to 2,686 veterinary students expected to graduate in spring 2012, and responses were received from 2,502 (93.1%). Information regarding year-2012 graduates employment choices, expected salaries, and estimated educational indebtedness was described in an earlier report.1 The results reported here include an analysis of that information according to gender and contain additional information on employment benefits and demographic characteristics. Of students that responded to the survey, 22.5% (563) were male and 77.5% (1,939) were female. Base sizes in the present report vary because some respondents did not answer all questions. Employment Preferences, Offers, and Acceptances At the time of the survey, 96.3% (2,410/2,502) of respondents indicated that they were actively seeking employment or advanced education in veterinary medicine. The remainder of respondents (3.7% [92]) indicated that they were not actively seeking such positions. Respondents seeking veterinary positions were asked to indicate their top 3 employment preferences. Employment preferences were similar between male and female respondents. Of 532 males and 1,872 females that answered the question, the first choice for both groups was employment in the private sector (67.9% [361] of males and 58.1% [1,088] of fePrepared by Allison J. Shepherd, MBA, and Laura Pikel, BS; from the Communications Division, AVMA, 1931 N Meacham Rd, Ste 100, Schaumburg, IL 60173. 1040 Vet Med Today: Facts & Figures

males), followed by advanced education (28.9% [154] of males and 37.6% [704] of females) and public and corporate employment (3.2% [17] of males and 4.0% [74] of females). The remainder of respondents (6) indicated preferences for other types of veterinary employment. Among respondents seeking veterinary positions, 62.1% (331/533) of males and 61.3% (1,151/1,877) of females had received 1 offer of employment or advanced education at the time of the survey. Of year-2012 male respondents with employment offers, 45.3% had > 1 offer and 11.9% had 4 offers (Table 1). Among year-2012 female respondents with employment offers, 33.5% had > 1 offer and 4.1% had 4 offers. The mean number of employment offers received was 2.0 for male and 1.5 for female respondents. Among those who had received offers, similar proportions of male and female respondents had accepted offers of employment (88.2% [292/331] of males and 89.1% [1,025/1,151] of females). These individuals represented 54.6% of respondents who indicated that they were seeking a veterinary position. Of the respondents who had accepted offers, 79.4% (231/291) of males and 85.5% (876/1,024) of females had accepted an offer that matched their first choice, whereas 8.9% (26) of males and 5.9% (60) of females had accepted an offer of employment or advanced education that was not among their top 3 choices. The distribution of respondents who had accepted veterinary positions was determined (Table 2). The types of employment accepted most often by male respondents were internship positions (37.3%), companion animal exclusive practice (25.7%), and mixed animal practice (12.7%). For female respondents, the

Table 1Distribution of numbers of offers of employment received by female and male year-2012 graduates of US veterinary medical schools and colleges. No. of offers 1 2 3 4 Female (n = 1,149) No. % 764 66.5 251 21.8 87 7.6 47 4.1 Male (n = 329) No. % 180 54.7 59 17.9 51 15.5 39 11.9

Surveys were sent to 2,686 veterinary medical students expected to graduate in spring 2012, and responses were received from 2,502; some respondents did not answer every question. Of 2,410 respondents seeking positions at the time of the survey, 1,482 had received 1 employment offer.

JAVMA, Vol 241, No. 8, October 15, 2012

positions accepted most often were internship positions (52.7%), companion animal exclusive practice (22.3%), and mixed animal practice (7.3%). Respondents entering internships were asked to provide their primary reason for undertaking an internship (Table 3). Most (53.2%) males indicated that they planned to apply for residency; 37.6% wanted to practice better quality veterinary medicine, and 5.5% believed they needed more training before entering veterinary practice. Among females, 41.3% indicated that they wanted to practice better quality veterinary medicine, 35.0% planned to apply for residency, and 20.9% believed they needed more training before entering veterinary practice. Very few (2.8% of males and 0.4% of females) cited earning more money in veterinary medicine as the primary reason they were undertaking an internship. Nearly all respondents entering private practice (99.1%; 98.1% [153/156] of males and 99.5% [378/380] of females) indicated they would be an employee rather than self-employed. Similar percentages of male and female respondents entering private practice expected to work full-time (98.7% [154/156] vs 97.9% [378/386], respectively).

Starting Salaries Survey questions allowed respondents to indicate various means by which they expected to be compensated for work (eg, base salary or stipend only, base salary or stipend with production bonus, and productionbased salary only [in lieu of base salary]). Respondents who accepted an offer of employment in 2012 were asked to indicate types of compensation expected. Among the 285 male respondents who indicated the type of full-time salary they would receive, 68.1% (194) indicated they would receive a guaranteed salary with no option for a production bonus, 28.1% (80) indicated they would receive a base salary with a production bonus, and 1.1% (3) indicated they would receive a salary fully based on production; 2.8% (8) were uncertain. Of 994 female respondents with full-time positions who answered this question, 78.7% (782) indicated they would receive a guaranteed salary with no option for a production bonus, 18.6% (185) indicated they would receive a base salary with a production bonus, 0.3% (3) indicated they would receive a salary fully based on production, and 2.4% (24) were uncertain. The mean number of hours that respondents expected

Table 2Distribution of employment types among year-2012 graduates* of US veterinary medical schools and colleges by gender. Practice type Food animal exclusive Food animal predominant Mixed animal Companion animal exclusive Companion animal predominant Equine Other private practice University Uniformed services State or local government Federal government Industry or commercial Not-for-profit Advanced education (total) Internship (private or academic) MBA MPH MPVM MS PhD Residency program Other advanced study Female (n = 1,025) No. % 8 13 75 229 44 18 2 5 13 1 7 2 6 602 540 0 7 1 1 12 34 7 0.8 1.3 7.3 22.3 4.3 1.8 0.2 0.5 1.3 0.1 0.7 0.2 0.6 58.7 52.7 0 0.7 0.1 0.1 1.2 3.3 0.7 Male (n = 292) No. % 11 3.8 17 5.8 37 12.7 75 25.7 14 4.8 3 1.0 1 0.3 2 0.7 4 1.4 0 0 1 0.3 2 0.7 0 0 125 109 0 0 0 1 2 11 2 42.8 37.3 0 0 0 0.3 0.7 3.8 0.7

*In total, 1,317 respondents had accepted employment offers at the time of the survey.

Table 3Distribution of primary reason for undertaking an internship for year-2012 graduates of US veterinary medical schools and colleges by gender. Reason To practice better quality veterinary medicine Need more training before entering veterinary practice Plan to apply for residency Feel I will earn more money in veterinary medicine by doing an internship Other Female (n = 535) No. % 221 112 187 2 41.3 20.9 35.0 0.4 Male (n = 109) No. % 41 6 58 3 37.6 5.5 53.2 2.8

13 2.4

1 0.9

JAVMA, Vol 241, No. 8, October 15, 2012

Vet Med Today: Facts & Figures

1041

to work each week was 56.5 (median, 55) for males and 59.1 (median, 60) for females. Mean full-time starting salaries in 2012 among all employer types combined (private, public, and corporate practice and advanced education programs) were $52,255 for male and $43,673 for female respondents (n = 282 and 990 reporting salaries, respectively; all salary values are reported in nominal dollars and have not been adjusted for inflation). When advanced education salaries were excluded from the analysis, mean fulltime starting salaries increased to $69,405 for males and $63,844 for females. Mean full-time starting salary for respondents who accepted an offer in private

practice was $69,873 for males (n = 150) and $64,457 for females (377; Figure 1). Among male respondents, full-time private practice salaries ranged from $65,265 for food animal predominant practice to $72,174 for companion animal exclusive practice. Among female respondents, full-time private practice salaries ranged from $35,389 for equine practice to $69,163 for companion animal predominant practice. Additional Compensation Respondents were asked whether they would receive a signing bonus, moving allowance, or emergency case compensation; multiple responses to the question were allowed. In total, 351 respondents (34.3% [98/286] of males and 25.5% [253/994] of females) expected to receive 1 of these types of compensation in addition to their salary. Of respondents who specified compensation types, a signing bonus was expected by 14.3% (14/98) of males and 9.5% (23/242) of females, a moving allowance was indicated by 31.6% (31) of males and 29.8% (72) of females, and emergency case compensation was expected by 72.4% (71) of males and 78.1% (189) of females. Additional Benefits

Figure 1Mean full-time starting salary of year-2012 male (white bars; n =150) and female (black bars; 377) graduates of US veterinary medical schools and colleges entering private practice. Salary information was provided by 527 of 547 respondents who had accepted private practice employment offers at the time of the survey. CAE = Companion animal exclusive. CAP = Companion animal predominant. EQU = Equine. FAE = Food animal exclusive. FAP = Food animal predominant. MIX = Mixed animal practice.

Respondents who accepted employment offers were asked to indicate the additional benefits that would be provided by their new employer. All but 2.2% of respondents (29/1,317; 3.1% [9/292] of males and 2.0% [20/1,025] of females) reported that they would receive 1 of the benefits listed in the survey. In 2012,

Figure 2Frequency distributions of benefits offered by employers to new graduates of US veterinary medical schools and colleges in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012. 1042 Vet Med Today: Facts & Figures JAVMA, Vol 241, No. 8, October 15, 2012

the compensation packages of more than half of the 1,317 respondents who accepted positions included medical-hospitalization plan (76.7% [1,010]), paid vacation leave (71.4% [940]), liability insurance (61.8% [814]), continuing education expenses (61.7% [813]), license fees (54.1% [712]), continuing education leave (50.3% [662]), and discounted pet care (50.6% [666]; Figure 2). Although the percentages of male and female respondents who expected to receive these benefits were fairly similar overall, the percentage of males indicating they would receive individual benefits was higher than that of females for most benefits (Table 4). Benefits for which the greatest distribution difference was detected between genders were association dues (54.1% of males vs 43.5% of females), tax-deferred retirement plans (29.1% of males vs 21.2% of females), paid legal holidays (29.5% of males vs 22.0% of females), and employer contribution to tax-deferred retirement plans

(22.6% of males vs 15.4% of females). The benefit reported most often by respondents of both genders was a medical-hospitalization plan (76.7% for both). Educational Indebtedness Most respondents had accumulated educational debt by the time they graduated. Among respondents who answered questions about debt in 2012, 12.3% (69/563) of males and 10.3% (200/1,938) of females did not incur any educational debt. Mean reported debt among respondents who had debt was $147,518 for males (n = 494) and $152,853 for females (1,738; all values for educational debt are reported in nominal dollars and have not been adjusted for inflation). Median debt of these individuals was $145,500 for males and $150,000 for females. Among those with debt, 23.1% (114/494) of males and 25.2% (438/1,738) of females had debt $200,000. Mean total educational debt for

Table 4Distribution of employment-related benefits offered by employers to year-2012 graduates of US veterinary medical schools and colleges by gender. Benefit Medical-hospitalization plan Dental plan Tax-deferred retirement plan Informal profit-sharing plan Employer contribution or match to tax-deferred retirement plan Life insurance Disability insurance Liability insurance Association dues License fees Continuing education expenses Continuing education leave Paid legal holidays Paid sick leave Paid vacation leave Personal use of vehicle Discounted pet care services Other Female (n = 1,025) No. % 786 374 217 15 158 163 276 630 446 538 626 500 76.7 36.5 21.2 1.5 15.4 15.9 26.9 61.5 43.5 52.5 61.1 48.8 Male (n = 292) No. % 224 98 85 9 66 54 87 184 158 174 187 162 76.7 33.6 29.1 3.1 22.6 18.5 29.8 63.0 54.1 59.6 64.0 55.5

226 22.0 396 38.6 727 70.9 96 9.4 512 50.0 65 6.3

86 29.5 122 41.8 213 72.9 47 16.1 154 52.7 17 5.8

Table 5Demographics of year-2012 graduates of US veterinary medical schools and colleges by gender. Characteristic Mean age (y) Marital status (%) Single Married Divorced Respondents with children (%) Race or ethnicity (%) White or Caucasian Black or African American Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander Other race or ethnicity Female Male All No. Value 1,937 1,350 524 51 93 1,707 44 54 82 41 27.6 70.1 27.2 2.6 4.8 88.5 2.3 2.8 4.3 2.1 No. Value 562 347 204 12 89 496 13 27 14 12 28.0 61.6 36.2 2.1 15.9 88.3 2.3 4.8 2.5 2.1 No. Value 2,499 1,697 728 63 182 2,203 57 81 96 53 27.7 68.2 29.3 2.5 7.3 88.5 2.3 3.3 3.9 2.1

Marital status information was provided by 1,925 females and 563 males. The total number of respondents that provided information on children was 1,934 females and 561 males. Information on race or ethnicity was provided by 1,928 females and 562 males. Units in parentheses apply to the value column. JAVMA, Vol 241, No. 8, October 15, 2012 Vet Med Today: Facts & Figures 1043

all respondents was $129,439 (median, $133,000) for males and $137,079 (median, $142,224) for females. The mean debt incurred for veterinary medical school education alone for all respondents was $119,686 (median, $122,800) for males and $125,989 (median, $130,000) for females. Graduate Characteristics Male and female veterinary students were approximately the same age at graduation (mean, 28.0 years for males [n = 562] and 27.6 years for females [1,937]; Table 5). The majority of respondents (88.3% of males Appendix

and 88.5% of females) described themselves as white or Caucasian. More than two-thirds (68.2%) of respondents were single and had never married; 61.6% of males and 70.1% of females were in this category. A higher percentage of males were married (36.2%), compared with the percentage of married females (27.2%), and a higher percentage of male respondents had children (15.9% of males, compared with 4.8% of females). Reference

1. Shepherd AJ, Pikel L. Employment, starting salaries, and educational indebtedness of year-2012 graduates of US veterinary medical colleges. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012;241:890894.

Response rates for the 28 schools and colleges of veterinary medicine in the United States that participated in the 2012 survey of new graduates.1 Veterinary school Auburn University Colorado State University Cornell Veterinary College Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University Iowa State University Kansas State University Louisiana State University Michigan State University Mississippi State University North Carolina State University The Ohio State University Oklahoma State University Oregon State University Purdue University Texas A&M University Tuskegee University University of California-Davis University of Florida University of Georgia University of Illinois University of Minnesota University of Missouri-Columbia University of Pennsylvania University of Tennessee University of Wisconsin Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine Washington State University Western University of Health Sciences Overall response rate Response rate of graduating class (%) 100 78 100 95 91 97 100 87 100 100 81 100 93 100 97 100 100 98 100 74 91 97 78 98 100 100 99 87 93

(Reprinted from Shepherd AJ, Pikel L. Employment, starting salaries, and educational indebtedness of year-2012 graduates of US veterinary medical colleges. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012;241:890 894. Reprinted with permission.)

1044

Vet Med Today: Facts & Figures

JAVMA, Vol 241, No. 8, October 15, 2012

You might also like

- Caregiving Full-Time and Working Full-Time: Managing Dual Roles and ResponsibilitiesFrom EverandCaregiving Full-Time and Working Full-Time: Managing Dual Roles and ResponsibilitiesNo ratings yet

- Nudge Database 1.1Document28 pagesNudge Database 1.1rajv88No ratings yet

- Ayoub Jumanne Proposal MzumbeDocument36 pagesAyoub Jumanne Proposal MzumbeGoodluck Savutu Lucumay50% (2)

- Animal Welfare AVMA Policy - Animals Used in Entertainment, Shows, and For ExhibitionDocument1 pageAnimal Welfare AVMA Policy - Animals Used in Entertainment, Shows, and For Exhibitionfreak009No ratings yet

- Changing Practice Patterns of Family Med PDFDocument9 pagesChanging Practice Patterns of Family Med PDFAlin DanciNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Rewards and Nurses' Work Motivation in Addis Ababa HospitalsDocument6 pagesRelationship Between Rewards and Nurses' Work Motivation in Addis Ababa Hospitalszaenal abidinNo ratings yet

- The Level of Empowerment of Overseas Filipino Women WorkersDocument82 pagesThe Level of Empowerment of Overseas Filipino Women WorkersEsttie RadamNo ratings yet

- Factors Considered by Undergraduate Medical Students When Selecting Specialty of Their Future CareersDocument6 pagesFactors Considered by Undergraduate Medical Students When Selecting Specialty of Their Future CareershelenaNo ratings yet

- Eportfolio EwellDocument7 pagesEportfolio Ewellapi-272863459No ratings yet

- Questionnaire Survey of Working Relationships Between Nurses and Doctors in University Teaching Hospitals in Southern NigeriaDocument22 pagesQuestionnaire Survey of Working Relationships Between Nurses and Doctors in University Teaching Hospitals in Southern NigeriaMin MinNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing The Choice of Specialty of Australian Medical GraduatesDocument6 pagesFactors Influencing The Choice of Specialty of Australian Medical GraduatesOlgaNo ratings yet

- Work-Related Fatigue Among Medical Personnel in TaiwanDocument8 pagesWork-Related Fatigue Among Medical Personnel in TaiwanfaridaNo ratings yet

- Behavior Management Techniques Among Pediatric Dentists Practicing in The SE United StatesDocument7 pagesBehavior Management Techniques Among Pediatric Dentists Practicing in The SE United StatesRocio FloresNo ratings yet

- IELTS Academic Reading 10Document4 pagesIELTS Academic Reading 10hỒ QuốcNo ratings yet

- Occupational Health and Safety Issues Among Nurses in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesOccupational Health and Safety Issues Among Nurses in The PhilippinesDani CawaiNo ratings yet

- High Rates of Burnout Among Maternal Health Staff at A Referral Hospital in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument22 pagesHigh Rates of Burnout Among Maternal Health Staff at A Referral Hospital in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional StudyRoan Khaye CuencoNo ratings yet

- Code Blue EmergenciesDocument17 pagesCode Blue EmergenciesEstherThompsonNo ratings yet

- Absenteeism in NursingDocument4 pagesAbsenteeism in NursingNGUYÊN PHẠM NGỌC KHÔINo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument15 pagesThesismarlynperez867173100% (1)

- Career Choice PHDocument8 pagesCareer Choice PHmahyudinimaNo ratings yet

- Fitzpatrick OriginalDocument6 pagesFitzpatrick OriginalKristianus S PulongNo ratings yet

- BMC Public HealthDocument5 pagesBMC Public HealthDag Eva SanthiNo ratings yet

- Title of The TopicDocument5 pagesTitle of The Topicchetan1309No ratings yet

- Final 2Document11 pagesFinal 2Kyla CostelloNo ratings yet

- Professional BurnoutDocument5 pagesProfessional BurnoutCristina SavaNo ratings yet

- Academic Emergency Medicine - 2008 - Hobgood - Medical Errors What and When What Do Patients Want To KnowDocument8 pagesAcademic Emergency Medicine - 2008 - Hobgood - Medical Errors What and When What Do Patients Want To Knowqualitymalak660No ratings yet

- Animals 03 00085Document24 pagesAnimals 03 00085Ishwarya RaghuNo ratings yet

- Absenteeism in NursingDocument5 pagesAbsenteeism in Nursingerica jayasunderaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument11 pagesJurnal InternasionalYeni SantikaNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction and Morale inDocument13 pagesJob Satisfaction and Morale inMoeshfieq WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Journal of Vocational Behavior: Kevin W. Glavin, George V. Richard, Erik J. PorfeliDocument6 pagesJournal of Vocational Behavior: Kevin W. Glavin, George V. Richard, Erik J. PorfeliRizma AdliaNo ratings yet

- BayyapareddyDocument8 pagesBayyapareddyeditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- 10th Biennial Monash Pharmacy Education Symposium 2019Document68 pages10th Biennial Monash Pharmacy Education Symposium 2019muveszsziNo ratings yet

- Ittner, Larcker & Pizzini (2007)Document28 pagesIttner, Larcker & Pizzini (2007)camihoangNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Rice Farmers Cross Sectional Study in Tarnlalord Sub-District, Phimai District, Nakhonratchasima Province, ThailandDocument7 pagesFactors Associated With Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Rice Farmers Cross Sectional Study in Tarnlalord Sub-District, Phimai District, Nakhonratchasima Province, ThailandArif Budi SantosoNo ratings yet

- Discussion Ed - Anshu Makol CHP V - FDocument15 pagesDiscussion Ed - Anshu Makol CHP V - FAnshu MakolNo ratings yet

- More - Annotated.articles TahaniBurtDocument4 pagesMore - Annotated.articles TahaniBurttahani burtNo ratings yet

- Absenteeism in Nursing: A Longitudinal StudyDocument4 pagesAbsenteeism in Nursing: A Longitudinal StudyHồ Thị Quỳnh AnhNo ratings yet

- A Survey of High School Seniors Career Choices - Implications ForDocument12 pagesA Survey of High School Seniors Career Choices - Implications ForMs. M. SupatNo ratings yet

- Quiz 1 SolutionsDocument4 pagesQuiz 1 Solutionstracer14No ratings yet

- Health and Fitness-A Study Among Fitness Centres in Panachikad Panchayat in Kottayam DistrictDocument5 pagesHealth and Fitness-A Study Among Fitness Centres in Panachikad Panchayat in Kottayam DistrictAnjaly SabuNo ratings yet

- Under-Reporting of Gravidity in A Rural Malawian PopulationDocument3 pagesUnder-Reporting of Gravidity in A Rural Malawian PopulationMisirihNo ratings yet

- Incentive For NurseDocument9 pagesIncentive For NurseAnis KhairunnisaNo ratings yet

- QuestionnaireDocument6 pagesQuestionnaireIshaq HameedahNo ratings yet

- A Gender Analysis of Job Satisfaction, Job Satisfier Factors, and Job Dissatisfier Factors of Agricultural Education TeachersDocument7 pagesA Gender Analysis of Job Satisfaction, Job Satisfier Factors, and Job Dissatisfier Factors of Agricultural Education TeachersAik MusafirNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Job Satisfaction and Stress Among Male and Female Doctors in Teaching Hospitals of KarachiDocument10 pagesComparison of Job Satisfaction and Stress Among Male and Female Doctors in Teaching Hospitals of KarachiayeshazubairNo ratings yet

- Absenteeism in Nursing:: A Longitudinal StudyDocument4 pagesAbsenteeism in Nursing:: A Longitudinal StudyMariaNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument9 pagesContent ServerSatriya PranataNo ratings yet

- J Jss 2017 05 075Document9 pagesJ Jss 2017 05 075NIWAYANRADHANo ratings yet

- Physician Assistants in Primary Care Trends and CharacteristicsDocument5 pagesPhysician Assistants in Primary Care Trends and CharacteristicsThe Physician Assistant LifeNo ratings yet

- Kupit 1Document16 pagesKupit 1wayan sudarsanaNo ratings yet

- Research Article - Burnout Among Nurses in A Nigerian General HospitalDocument7 pagesResearch Article - Burnout Among Nurses in A Nigerian General HospitalAndrei AlexandruNo ratings yet

- 2010 Workforce Trends in OTDocument2 pages2010 Workforce Trends in OTVasilache DeliaNo ratings yet

- Work Support, Psychological Well-Being and Safety Performance Among Nurses in Hong KongDocument7 pagesWork Support, Psychological Well-Being and Safety Performance Among Nurses in Hong KongAshleigh Joyz LamNo ratings yet

- Lowenstein Et Al 2007 Medical School Faculty DiscontentDocument8 pagesLowenstein Et Al 2007 Medical School Faculty Discontentapi-264671444No ratings yet

- 3drseetharaman Full Text With Cover Page v2Document9 pages3drseetharaman Full Text With Cover Page v2pushpal1966No ratings yet

- Osh Evaluation ReducedDocument12 pagesOsh Evaluation ReducedEneyo VictorNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction and Associated Factors Among Health Professionals Working at Western Amhara Region, EthiopiaDocument7 pagesJob Satisfaction and Associated Factors Among Health Professionals Working at Western Amhara Region, EthiopiaJesille Lynn MoralaNo ratings yet

- DiscussionDocument3 pagesDiscussionMominah MayamNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Managed Care On The Practice of Psychological Testing Preliminary FindingsDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Managed Care On The Practice of Psychological Testing Preliminary FindingsCristóbal Cortázar MorizonNo ratings yet

- Closing the Gender Pay Gap in Medicine: A Roadmap for Healthcare Organizations and the Women Physicians Who Work for ThemFrom EverandClosing the Gender Pay Gap in Medicine: A Roadmap for Healthcare Organizations and the Women Physicians Who Work for ThemAmy S. Gottlieb, MD, FACPNo ratings yet

- A A Ep Care Guidelines RR 2012Document36 pagesA A Ep Care Guidelines RR 2012freak009No ratings yet

- Dry Cow Protocol: Internal Teat SealantDocument1 pageDry Cow Protocol: Internal Teat Sealantfreak009No ratings yet

- Ethical and Professional Guidelines: Position Statement Protocol (2010)Document29 pagesEthical and Professional Guidelines: Position Statement Protocol (2010)freak009No ratings yet

- Bio Security Guidelines Final 030113Document5 pagesBio Security Guidelines Final 030113freak009No ratings yet

- Parasite Control Guidelines FinalDocument24 pagesParasite Control Guidelines Finalfreak009No ratings yet

- Equine Herpesvirus Myeloencephalopathy (EHM) & EHV-1: Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument2 pagesEquine Herpesvirus Myeloencephalopathy (EHM) & EHV-1: Frequently Asked Questionsfreak009No ratings yet

- Herd Health Protocols For The Cowherd: MLV VaccineDocument1 pageHerd Health Protocols For The Cowherd: MLV Vaccinefreak009No ratings yet

- Herd Health Protocols For Heifers: Clostridium Type A SeleniumDocument1 pageHerd Health Protocols For Heifers: Clostridium Type A Seleniumfreak009No ratings yet

- Biosecurity On Dairies: A BAMN PublicationDocument4 pagesBiosecurity On Dairies: A BAMN Publicationfreak009No ratings yet

- Beef Vax ProtocolDocument3 pagesBeef Vax Protocolfreak009No ratings yet

- Bio SecurityDocument2 pagesBio Securityfreak009No ratings yet

- Management Cycles in Beef Production: F. Glen HembryDocument14 pagesManagement Cycles in Beef Production: F. Glen Hembryfreak009No ratings yet

- Energy and Prox AnalysisDocument4 pagesEnergy and Prox Analysisfreak009No ratings yet

- Beef Herd Health CalanderDocument4 pagesBeef Herd Health Calanderfreak009No ratings yet

- A Guide To Calf Milk Replacers Types, Use and QualityDocument4 pagesA Guide To Calf Milk Replacers Types, Use and Qualityfreak009No ratings yet

- Foreign Animal Diseases: USDA Select Agent and Toxin ListDocument17 pagesForeign Animal Diseases: USDA Select Agent and Toxin Listfreak009No ratings yet

- Beef Cattle Vax Protocol2Document4 pagesBeef Cattle Vax Protocol2freak009No ratings yet

- Biosec Ip Dairy HerdsDocument4 pagesBiosec Ip Dairy Herdsfreak009No ratings yet

- Beef0708 Is BiosecurityDocument4 pagesBeef0708 Is Biosecurityfreak009No ratings yet

- Beef Cattle Vax ProtocolDocument2 pagesBeef Cattle Vax Protocolfreak009No ratings yet

- Restraint of The Savage BeastDocument2 pagesRestraint of The Savage Beastfreak009No ratings yet

- Feeding Dogs: Taxonomic ClassificationDocument8 pagesFeeding Dogs: Taxonomic Classificationfreak009No ratings yet

- Guide To Admissions (Supplement-M) 2014-15: Aligarh Muslim UniversityDocument7 pagesGuide To Admissions (Supplement-M) 2014-15: Aligarh Muslim UniversityscribedmastNo ratings yet

- Nbe Book FinalDocument80 pagesNbe Book FinalJoyee BasuNo ratings yet

- ShelbyschroederresumeDocument2 pagesShelbyschroederresumeapi-310782911No ratings yet

- Observer Application: General Personal InformationDocument3 pagesObserver Application: General Personal InformationDragomir IsabellaNo ratings yet

- MBBS Phase I CBME Curriculum 2019 20Document108 pagesMBBS Phase I CBME Curriculum 2019 20MANOJ HEMADRINo ratings yet

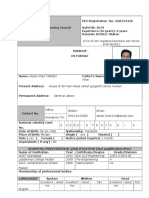

- (Cvs of Non Registered Persons Will Not Be Entertained.) : Academic/Professional Qualification (Last Qualification First)Document3 pages(Cvs of Non Registered Persons Will Not Be Entertained.) : Academic/Professional Qualification (Last Qualification First)Arsmar ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Indra AdisusiantoDocument7 pagesIndra AdisusiantoFabri Drajat SantosoNo ratings yet

- Melb Uni Internship Directory 2011 by CountryDocument96 pagesMelb Uni Internship Directory 2011 by CountryPruet PanpruetNo ratings yet

- Jfe Science Abstracts 2019Document31 pagesJfe Science Abstracts 2019api-308218624No ratings yet

- CRPFDocument14 pagesCRPFsandeep420No ratings yet

- 28th AFIH ADVERTISEMENT 2021Document16 pages28th AFIH ADVERTISEMENT 2021Manjunath ShivakumarNo ratings yet

- Internship Completion CertificateDocument2 pagesInternship Completion CertificateAvdhoot ShimpiNo ratings yet

- Advert - Medical Paramedics Interns - Ministry of Health - County Governments 16th Jan 2020Document4 pagesAdvert - Medical Paramedics Interns - Ministry of Health - County Governments 16th Jan 2020james metoboNo ratings yet

- Information Bulletin NEET MDS 2021 - Final Version For WebsiteDocument89 pagesInformation Bulletin NEET MDS 2021 - Final Version For Websiteshafali agrawalNo ratings yet

- RegistrationForm 1Document7 pagesRegistrationForm 1DrPawan BhardwajNo ratings yet

- AMSA Internship GuideDocument88 pagesAMSA Internship GuideiamseraNo ratings yet

- Medecine en FranceDocument2 pagesMedecine en FrancetasiambdNo ratings yet

- Contract of Employment For Non-Consultant Hospital DoctorsDocument17 pagesContract of Employment For Non-Consultant Hospital DoctorsJahangir AlamNo ratings yet

- Advertisment On Adhoc Basis Recruitment For 01 - 07Document2 pagesAdvertisment On Adhoc Basis Recruitment For 01 - 07Raghav PratapNo ratings yet

- BSEd in Physical Education in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesBSEd in Physical Education in The PhilippinesJuliefer Ann GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Medical Titles (8!9!2015)Document40 pagesMedical Titles (8!9!2015)Vin BitzNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae Ronal KumarDocument4 pagesCurriculum Vitae Ronal KumarMuhammad Zahid FaridNo ratings yet

- PDFViewerDocument34 pagesPDFViewerKRISHNA KSNo ratings yet

- Chinese Government ScholarshipsDocument2 pagesChinese Government ScholarshipsAkbar SyahbanaNo ratings yet

- Report Format For OLD BHMDocument11 pagesReport Format For OLD BHMArun KarkiNo ratings yet

- CVDocument17 pagesCVLidya IkaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Emergency Management Program: Advanced WorkshopDocument4 pagesClinical Emergency Management Program: Advanced WorkshopNataraj ThambiNo ratings yet

- BDS Regulations HAND BOOK 2013-14 PDFDocument135 pagesBDS Regulations HAND BOOK 2013-14 PDFSayeeda MohammedNo ratings yet

- Form New Format PDFDocument13 pagesForm New Format PDFANCIENT MYSTERIES OF THE WORLDNo ratings yet

- Office OF THE Student Regent: Matters Arising From The Previous MinutesDocument80 pagesOffice OF THE Student Regent: Matters Arising From The Previous MinutesOffice of the Student Regent, University of the PhilippinesNo ratings yet