Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(2008) L.Q.R., 124 (Oct), 539-543 Goh Yi Han - Duty of Care in Psychiatric Harm Cases in Singapore

(2008) L.Q.R., 124 (Oct), 539-543 Goh Yi Han - Duty of Care in Psychiatric Harm Cases in Singapore

Uploaded by

Wei Ren LimCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 8 Requisitions On TitleDocument14 pages8 Requisitions On Titleapi-3803117No ratings yet

- Claims Entitled To Contractor According To Fidic Red Book 2017Document2 pagesClaims Entitled To Contractor According To Fidic Red Book 2017Omar Hany100% (5)

- Company Law Reform in Malaysia: The Role and Duties of DirectorsDocument15 pagesCompany Law Reform in Malaysia: The Role and Duties of DirectorsBenjamin Goo KWNo ratings yet

- Sublease FormatDocument6 pagesSublease FormatMarieTeeNo ratings yet

- Law On SALES FInal ExamsDocument9 pagesLaw On SALES FInal ExamsKitem Kadatuan Jr.100% (2)

- JCT ExplanationDocument58 pagesJCT ExplanationSuraj Sirinaga100% (2)

- PDF Psychometrics An Introduction 3Rd Edition Michael Furr Ebook Full ChapterDocument41 pagesPDF Psychometrics An Introduction 3Rd Edition Michael Furr Ebook Full Chapterelenor.grimshaw491100% (1)

- San Juan vs. CADocument16 pagesSan Juan vs. CADorky DorkyNo ratings yet

- Brochure y Planimetro en Ingles Daniela CastilloDocument9 pagesBrochure y Planimetro en Ingles Daniela CastilloDaniela Castillo LugoNo ratings yet

- ObliCon Case DigestDocument19 pagesObliCon Case DigestJo Ellaine Torres100% (1)

- DeceitDocument15 pagesDeceitAnchita BerryNo ratings yet

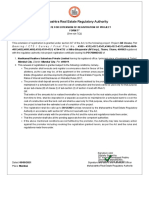

- Maharashtra Real Estate Regulatory Authority: Certificate For Extension of Registration of Project Form 'F'Document1 pageMaharashtra Real Estate Regulatory Authority: Certificate For Extension of Registration of Project Form 'F'Dipesh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Date: December 26, 1964 Ponente: Bengzon, J.P., J. Plaintiff-Appellee: Beatriz P. Wassmer Defendant-Appellant: Francisco X. Velez FactsDocument3 pagesDate: December 26, 1964 Ponente: Bengzon, J.P., J. Plaintiff-Appellee: Beatriz P. Wassmer Defendant-Appellant: Francisco X. Velez FactsJlo HeheNo ratings yet

- SALEDocument2 pagesSALELyding BaristaNo ratings yet

- Procedure For Grant of PatentDocument3 pagesProcedure For Grant of PatentMeghan Kaye LiwenNo ratings yet

- Course Outline For Intellectual Property RightsDocument4 pagesCourse Outline For Intellectual Property Rightschikumbutso chimbatataNo ratings yet

- Family Code Complete Set of Digested Cases BedaDocument222 pagesFamily Code Complete Set of Digested Cases BedaRyan Heynrich Misa100% (1)

- Pointers To Review LAW 1Document7 pagesPointers To Review LAW 1Well Ann SimaraNo ratings yet

- Master Deed and Declaration of Restrictions For Wind Residences Page 1 of 4Document1 pageMaster Deed and Declaration of Restrictions For Wind Residences Page 1 of 4Elaisa Kasan100% (1)

- Form 8Document9 pagesForm 8lacatancopycentreNo ratings yet

- Cronos Technologies LLCDocument6 pagesCronos Technologies LLCPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Perez, Nuguid v. NuguidDocument6 pagesPerez, Nuguid v. NuguidPepper PottsNo ratings yet

- Easement and Right of Way For Electric Power Utilities AgreementDocument2 pagesEasement and Right of Way For Electric Power Utilities AgreementDario G. TorresNo ratings yet

- Case Digest SET 2Document7 pagesCase Digest SET 2Ma Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Purchase Agreement - 1Document4 pagesExclusive Purchase Agreement - 1vafranciNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Incoterms - Shipping SolutionsDocument24 pagesAn Introduction To Incoterms - Shipping SolutionsVincent LawNo ratings yet

- Civil LawDocument4 pagesCivil LawtynajoydelossantosNo ratings yet

- Civ DigestsDocument492 pagesCiv DigestsAnge Buenaventura SalazarNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspects of Business 2 MarksDocument7 pagesLegal Aspects of Business 2 MarksSivagnanaNo ratings yet

- Annexure-A To H-11-12-2019Document10 pagesAnnexure-A To H-11-12-2019Rohit nandiNo ratings yet

(2008) L.Q.R., 124 (Oct), 539-543 Goh Yi Han - Duty of Care in Psychiatric Harm Cases in Singapore

(2008) L.Q.R., 124 (Oct), 539-543 Goh Yi Han - Duty of Care in Psychiatric Harm Cases in Singapore

Uploaded by

Wei Ren LimOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(2008) L.Q.R., 124 (Oct), 539-543 Goh Yi Han - Duty of Care in Psychiatric Harm Cases in Singapore

(2008) L.Q.R., 124 (Oct), 539-543 Goh Yi Han - Duty of Care in Psychiatric Harm Cases in Singapore

Uploaded by

Wei Ren LimCopyright:

Available Formats

http://international.westlaw.com.lawproxy1.nus.edu.sg/print/p...

Westlaw Delivery Summary Report for 2,IP

Your Search: Date/Time of Request: Client Identier: Database: Citation Text: Lines: Documents: Images:

"Mustapha v. Culligan" Friday, March 1, 2013 23:22 Central IP USER USER-DEFINED-MB L.Q.R. 2008, 124(Oct), 539-543L.Q.R. 2008, 124(Oct), 539-543 211 1 0

The material accompanying this summary is subject to copyright. Usage is governed by contract with Thomson Reuters, West and their afliates.

L.Q.R. 2008, 124(Oct), 539-543 (Cite as: ) L.Q.R. 2008, 124(Oct), 539-543

Law Quarterly Review

2008

Duty of care in psychiatric harm cases in Singapore

Goh Yihan

2013 Sweet & Maxwell and its Contributors

Subject: Personal injury. Other Related Subject: Mental health

Keywords: Depression; Duty of care; Psychiatric harm; Road trafc accidents; Singapore

Cases cited: Page v Smith [1996] A.C. 155 (HL) Seng v Hock [2008] S.G.C.A. 23 (CA (Sing))

*539 AS with classics in the contemporary mass-market theatrical scene, legal classics appear to come in trilogies as well. Nowhere is this more aptly demonstrated than in tort law, where the three most important cases dening the test for duty of care in negligence are Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] A.C. 563, Anns v Merton LBC [1978] A.C. 728 and Caparo Industries Plc v Dickman [1990] 2 A.C. 605. However, to suggest that the difculties in negligence law have been claried by these cases would be inaccurate. Indeed, not only is the actual test for duty of care unclear in England (see, e.g. Customs and Excise Commissioners v Barclays Bank Plc [2007] 1 A.C. 181), the test for duty of care in psychiatric harm cases is even more unsatisfactory. The Singapore Court of Appeal has recently attempted to resolve these difculties. It rst held in Spandeck Engineering (S) Pte Ltd v

1 of 4

2/3/13 12:22 AM

http://international.westlaw.com.lawproxy1.nus.edu.sg/print/p...

Defence Science & Technology Agency [2007] 4 S.L.R. 100 that the generally applicable test for duty of care in Singapore is essentially the two-stage Anns test (of proximity and policy considerations) irrespective of the type of damage claimed. It has now in Ngiam Kong Seng v Lim Chiew Hock [2008] SGCA 23 extended the Anns test to duty of care in psychiatric harm cases, while rejecting the English position in Page v Smith [1996] 1 A.C. 155.

The facts in Ngiam were that the rst appellant was involved in a road accident allegedly caused by the respondent. The nature of the accident not being known to the second appellant (the wife of the rst appellant), the respondent represented himself as a bystander who had assisted the rst appellant. Eventually, the second appellant discovered the respondent's involvement in the accident and suffered from major depression resulting from her perceived betrayal. She sued the respondent for negligence on the basis that her depression resulted from the respondent's misinformation as to his involvement in the accident.

*540 The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge's decision to dismiss the second appellant's claim as the respondent owed no duty of care to her, and declined to follow Page in the process. As is well known, the majority's approach in Page distinguished between primary and secondary victims: the former being one who suffered psychiatric harm from fear of physical injury to himself, whereas the latter one who suffered psychiatric harm from fear of the safety of others. Pursuant to this distinction, a duty of care is owed to a primary victim if physical damage was reasonably foreseeable, even if psychiatric damage was not. On the other hand, secondary victims needed to show that psychiatric harm was reasonably foreseeable. In Ngiam, the Court of Appeal disregarded the distinction between primary and secondary victims and held that the Anns test applied for duty of care in psychiatric harm cases, although certain factual prerequisites must rst be met. First, the type of injury suffered must be a recognisable psychiatric illness, and secondly, it must be factually foreseeable that harm of some kind would be sustained as a result of the negligence, although (as will be seen) the exact kind of harm required is unclear.

While the rejection of Page is unlikely to be controversial, Ngiam itself is not without difculties. In applying the Anns test to psychiatric harm cases, the Court of Appeal reiterated that the requirement of foreseeability is merely a factual one. While it has been said that reasonable foreseeability has long been at the heart of duty of care jurisprudence (see Amirthalingam, Rening the Duty of Care in Singapore (2008) 124 L.Q.R. 42), it may well be that the concept of proximity itself represents a legal (or normative) concept of reasonable foreseeability. In other words, where there is legal proximity, the requirement of foreseeability would already have been fullled insofar as it is a facet (but not direct mirror) of the former, with the consequence that foreseeability serves no independent value on its own as a legal requirement. This approach is a defensible one so long as the denition of what is to be foreseen is a wide one. Foreseeability in psychiatric harm cases has hitherto been dened in a rather specic (and narrow) manner and in fact parallels the test for remoteness (i.e. that the kind of harm suffered must be foreseeable although its particular nature, extent or manner of its iniction need not: see The Wagon Mound (No.1) [1961] A.C. 388). If the requirement of foreseeability is so narrowly dened as to constitute a separate legal requirement which no longer nds expression within the requirement of proximity, then it arguably could be reinstated as such (subject to the problem of replicating the test for remoteness). This would occur if, for example, notwithstanding very close relational and spatial proximity, psychiatric harm were not reasonably foreseeable owing to the nature of an incident. In such a case, foreseeability would serve the distinct *541 function of conditioning liability by reference to the criterion of specic harm, one not reected in the requirement of proximity. Accordingly, the characterisation of foreseeability as a factual requirement in Ngiam only makes sense if what is to be foreseen is dened widely.

However, Ngiam seemingly left open the question of what is to be foreseen. On the one hand, in rejecting the distinction between primary and secondary victims in Page, the Court of Appeal might have taken the narrower view that foreseeability of psychiatric harm was required. In fact, it had referred to the need to establish factual foreseeability in the context of psychiatric harm (at [110]). Yet, on the other hand, in applying the factual requirement of foreseeability, the court apparently adopted a wider denition of what was to be foreseen: the foreseeability of harm as opposed to a specic kind of harm (at [132]). Moreover, the court alluded to the naturally wide ambit of (factual) foreseeability: surely the foreseeability of a specic type of harm is unlikely to be satisfactorily described as naturally wide? If the wider denition was what the court intended, there is no harm in relegating foreseeability to a merely factual requirement. This in fact mirrors the approach in Spandeck, in which was held that the foreseeability of economic loss, a specic kind of harm, belonged to the realm of remoteness. This may represent a subtle if signicant departure from existing jurisprudence by dening the scope of duty widely while leaving the question of whether a specic kind of harm is compensable to the stage of remoteness (an approach adopted in Attia v British Gas Plc [1988] Q.B. 304

2 of 4

2/3/13 12:22 AM

http://international.westlaw.com.lawproxy1.nus.edu.sg/print/p...

at 314, 319; King v Phillips [1953] 1 Q.B. 429 at 440). This was also arguably the approach adopted in the recent Canadian Supreme Court decision of Mustapha v Culligan of Canada Ltd [2008] SCC 27. In that case, which concerned a claim for psychiatric harm owing to the plaintiff seeing a dead y in a bottle of water, the Supreme Court adopted the Anns test at the duty stage without considering whether psychiatric harm was foreseeable. Instead, it too had left that question to the remoteness stage (at [18]). Conceptually, there is some attractiveness to dening the scope of duty of care widely and leaving the foreseeability of the specic kind of harm suffered to the remoteness stage. Indeed, if the scope of duty is dened so precisely as to reect the kind of harm which should be recoverable, then this replicates the function of the remoteness test as currently envisaged under The Wagon Mound (No.1) and serves no independent utility of its own. It is noteworthy that in cases such as Caparo, the foreseeability requirement was referred simply to that of damage, without any express specication. If the concern in formulating these legal control mechanisms is to prevent a ood of litigation, then it would not matter when the objection is raised but it may be important to ensure a conceptually consistent and nonrepetitive analytical legal framework.

*542 It was also indicated in Ngiam that the hitherto threshold requirement of a recognisable psychiatric illness be regarded as a consideration under the rubric of damage (at [97]). It is true that decisions have characterised the requirement of recognisable psychiatric illness as a threshold one (see, e.g. McLoughlin v O'Brian [1983] 1 A.C. 410 at 431), implying that it is considered even before issues of liability and damage. However, it could be conceptually benecial to clarify that this threshold requirement is, in fact, founded on the trite principle that the plaintiff ought to prove his loss, and such loss, in psychiatric harm cases, is simply a recognisable medical condition and not everyday sorrow. The requirement is only a threshold one insofar as there exists in most jurisdictions a summary procedure for the defendant to strike out the plaintiff's claim for it as completely baseless at the outset instead of waiting for the full trial.

The Court of Appeal in Ngiam has continued to move towards a general two-stage legal framework for duty of care analysis as envisaged in Spandeck for all claims in negligence regardless of the type of damage. This is a laudable approach. There is nothing inherent in the type of damage (whether physical, psychiatric or economic) that necessitates a different legal approach, and to continue with a different approach depending on the type of damage claimed would be doctrinally untidy and, more pertinently, would not address the concern of indeterminate liability that sometimes (but not always) results from claims of differing natures. Where foreseeability is dened widely, then, having recourse to the neighbour principle and restricting duty of care to its most essential characteristics, viz. proximity and policy considerations, the Anns test (as adopted in Spandeck and Ngiam ) would achieve the same result as the three-part Caparo test given that the factual conception of reasonable foreseeability is almost always satised. There is no reason why this cannot be applied in cases of psychiatric harm, as the Court of Appeal demonstrated in Ngiam. The challenge is to recognise that the concept of proximity is not easily dened, and that there could arise different kinds of proximity in different factual scenarios. However, this is a factual differentiation within the legal requirement of proximity, which insists on the closeness of the relationship between the parties, and which can be supported, in psychiatric harm cases, by the tripartite proximities of relational, spatial and manner of iniction identied by Lord Wilberforce in McLoughlin. The focus on proximity, while difcult, is inevitable given that very basis of a duty of care lies in the relationship between two parties.

Ultimately, the analysis undertaken by the Court of Appeal in Ngiam, in rejecting Page and analysing duty of care in psychiatric harm cases under a general legal framework equally applicable to other claims in negligence, is a fresh approach to an old problem. Instead of opening new difculties by way of the introduction of new tests to new scenarios, *543 the approach in Ngiam (as derived from Spandeck ) returns to the root of the neighbour principle in Donoghue and puts the focus squarely and sharply on the requirement of proximity to establish a duty of care in all cases. This does bring with it some measure of certainty in that only one test applies to all types of damage claimed, but the difculties of dening proximity will have to be confronted on a case-by-case basis. However, there remains scope for further clarication, particularly with respect to whether the Court of Appeal intended to relegate specic foreseeability to an issue of remoteness, or if the same is still retained at the duty of care stage dening the scope of such duty, albeit as a factual requirement. Perhaps, as with legal classics elsewhere, a third instalment in a trilogy of decisions from the same court is required.

GOH YIHAN.12

3 of 4

2/3/13 12:22 AM

http://international.westlaw.com.lawproxy1.nus.edu.sg/print/p...

1. National University of Singapore. 2. Depression; Duty of care; Psychiatric harm; Road trafc accidents; Singapore

END OF DOCUMENT 2013 Thomson Reuters.

4 of 4

2/3/13 12:22 AM

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 8 Requisitions On TitleDocument14 pages8 Requisitions On Titleapi-3803117No ratings yet

- Claims Entitled To Contractor According To Fidic Red Book 2017Document2 pagesClaims Entitled To Contractor According To Fidic Red Book 2017Omar Hany100% (5)

- Company Law Reform in Malaysia: The Role and Duties of DirectorsDocument15 pagesCompany Law Reform in Malaysia: The Role and Duties of DirectorsBenjamin Goo KWNo ratings yet

- Sublease FormatDocument6 pagesSublease FormatMarieTeeNo ratings yet

- Law On SALES FInal ExamsDocument9 pagesLaw On SALES FInal ExamsKitem Kadatuan Jr.100% (2)

- JCT ExplanationDocument58 pagesJCT ExplanationSuraj Sirinaga100% (2)

- PDF Psychometrics An Introduction 3Rd Edition Michael Furr Ebook Full ChapterDocument41 pagesPDF Psychometrics An Introduction 3Rd Edition Michael Furr Ebook Full Chapterelenor.grimshaw491100% (1)

- San Juan vs. CADocument16 pagesSan Juan vs. CADorky DorkyNo ratings yet

- Brochure y Planimetro en Ingles Daniela CastilloDocument9 pagesBrochure y Planimetro en Ingles Daniela CastilloDaniela Castillo LugoNo ratings yet

- ObliCon Case DigestDocument19 pagesObliCon Case DigestJo Ellaine Torres100% (1)

- DeceitDocument15 pagesDeceitAnchita BerryNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra Real Estate Regulatory Authority: Certificate For Extension of Registration of Project Form 'F'Document1 pageMaharashtra Real Estate Regulatory Authority: Certificate For Extension of Registration of Project Form 'F'Dipesh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Date: December 26, 1964 Ponente: Bengzon, J.P., J. Plaintiff-Appellee: Beatriz P. Wassmer Defendant-Appellant: Francisco X. Velez FactsDocument3 pagesDate: December 26, 1964 Ponente: Bengzon, J.P., J. Plaintiff-Appellee: Beatriz P. Wassmer Defendant-Appellant: Francisco X. Velez FactsJlo HeheNo ratings yet

- SALEDocument2 pagesSALELyding BaristaNo ratings yet

- Procedure For Grant of PatentDocument3 pagesProcedure For Grant of PatentMeghan Kaye LiwenNo ratings yet

- Course Outline For Intellectual Property RightsDocument4 pagesCourse Outline For Intellectual Property Rightschikumbutso chimbatataNo ratings yet

- Family Code Complete Set of Digested Cases BedaDocument222 pagesFamily Code Complete Set of Digested Cases BedaRyan Heynrich Misa100% (1)

- Pointers To Review LAW 1Document7 pagesPointers To Review LAW 1Well Ann SimaraNo ratings yet

- Master Deed and Declaration of Restrictions For Wind Residences Page 1 of 4Document1 pageMaster Deed and Declaration of Restrictions For Wind Residences Page 1 of 4Elaisa Kasan100% (1)

- Form 8Document9 pagesForm 8lacatancopycentreNo ratings yet

- Cronos Technologies LLCDocument6 pagesCronos Technologies LLCPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Perez, Nuguid v. NuguidDocument6 pagesPerez, Nuguid v. NuguidPepper PottsNo ratings yet

- Easement and Right of Way For Electric Power Utilities AgreementDocument2 pagesEasement and Right of Way For Electric Power Utilities AgreementDario G. TorresNo ratings yet

- Case Digest SET 2Document7 pagesCase Digest SET 2Ma Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Purchase Agreement - 1Document4 pagesExclusive Purchase Agreement - 1vafranciNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Incoterms - Shipping SolutionsDocument24 pagesAn Introduction To Incoterms - Shipping SolutionsVincent LawNo ratings yet

- Civil LawDocument4 pagesCivil LawtynajoydelossantosNo ratings yet

- Civ DigestsDocument492 pagesCiv DigestsAnge Buenaventura SalazarNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspects of Business 2 MarksDocument7 pagesLegal Aspects of Business 2 MarksSivagnanaNo ratings yet

- Annexure-A To H-11-12-2019Document10 pagesAnnexure-A To H-11-12-2019Rohit nandiNo ratings yet