Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Failed Solutions

Failed Solutions

Uploaded by

Nick BarcenasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Failed Solutions

Failed Solutions

Uploaded by

Nick BarcenasCopyright:

Available Formats

FAILED SOLUTIONS

POSTED BY ABBY CALLARD ON DECEMBER 31, 2010

This story originally appeared in our December 31, 2010 e-magazine. Click here to subscribe. By 2030, more than half the worlds population will live in cities. How will they cope? The worlds quick urbanizationeven faster in developing countrieshas put a strain on the cities expected to absorb the massive increase in residents. The issue of urbanization is not new, but the UN estimates that by 2030, 60% of the worlds population will live in cities. Most of the growth will come from developing countries. For example, McKinsey Global Institute estimates 40% of Indias population will live in cities by 2030a net increase of 250 million people. Cities, both in developed and developing countries, have struggled with providing affordable housing for their residents. In an effort to learn from past mistakes, were profiling three failed solutions: Cabrini-Green in Chicago, slum redevelopment in Mumbai and Fuerte Apache in Buenos Aires. Cabrini-Green Located at the intersection of two of Chicagos richest neighborhoods, Cabrini-Green is one of the most notorious public housing experiments in the world. Construction on the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) project startedin 1942 and ended in 1962. In the beginning, most of the residents held jobs at nearby factories. After World War II, the factories closed. To cut costs, the cities paved over the lawns to reduce maintenance, neglected repairs and finished the last buildings with questionable quality. Through the years, gangs moved in and controlled single buildings in the complex. Steel fences were put up around the perimeter. The fences made it hard for police officers to see inside the complex, and in 1970, two were killed by snipers from inside. The high balconiesgot to be so dangerous that CHA enclosed the entire height of the buildings with steel mesh. Many say this created the perception that residents were imprisoned. Pipes frequently burst, garbage backed up to the 15th floor in the trash chute and gang violence increased. Overthe years, gang violence and neglect created terrible conditions forthe residents, and the name Cabrini-Green became symbolic of theproblems associated with public housing in this country said Keith Gottfried, General Counsel of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, at a 2006 housing conference in Chicago. The last of the residents left earlier this month, and demolition of the last standing building, located at 1230 N. Burling, will begin early 2011. The reality is that 1230 N. Burling is in disrepair and CHA, in good conscience, could not allow good people to stay there any longer than what was necessary, said CEO Lewis A. Jordan. Slum Redevelopment

In a city where more than half the population resides in slums, Mumbais redevelopment plans are plentiful. So far, no single plan has been able to really pinpoint exactly how to solve the issue. But, many have failed. Unfinished buildings soar above the slums that have materialized waiting for the construction to be completed. Scaffolding and metal stick out at odd angles, and tarps flap in the wind. Below, people wait to move in. One man, with a family of 5, has been waiting for more than three years for an apartment. Construction on the building stalled two years ago and hasnt started again. While slum dwellers do not own the land on which they live, many own their houses and others pay rent. A 6-foot by 6foot room can rent for as much as INR 1,500 (US$33) a month. Most of them are reluctant to leave their homes. Another development, located in the far-east suburbs, was developed as an improvement from slum life, but fell short.Slum dwellers who qualified were entered into a lottery. Winners got a 225-square-foot apartment in the Lallubhai compound, which was completed in 2003. But the complex has been plagued with problems since construction finished. Trash collection is all but non-existent, and two wells serve the 11,000 residents. Because there are no elevators, residents have to carry water up to the apartments. Many of the wells are poorly constructed, and illegal wells are cropping up between buildings. This opens the community up to water-borne diseases. Fuerte Apache Barrio Ejrcito de los Andes, more commonly known as Fuerte Apache, in Buenos Aires grew from Argentinean dictator Juan Carlos Onganas plan to eliminate illegal settlements, called emergency villages. The project, started in 1966, was constructed in phases with one of them leading up to the 1978 World Cup. The settlement was envisioned as a well-protected depository for the poor in advance of the World Cup. Many of the residents were pulled from the Villa 31 slum in Retiro, an upper-class residential area. As of the 2001 census, 35,000 people lived in almost 5,000 residences. The number of actual residents is most likely much higher. Some estimate up to 100,000 live in the 26-acre neighborhood. The complex includes 33 towers, linked byhallways in three different groups, and 52 smaller freestanding buildings. This separation has alienated residents of different buildings, and conflicts have erupted because of the lack of communication. The area quickly earned a bad reputation for violence, drugs and crumbling buildings. Better Than Before The failures in Chicago, Mumbai and Buenos Aires can be directly attributed to oversight on behalf of development authorities and their partners. By not accounting for the fundamental building blocks of infrastructure and safety, these housing solutions were doomed from the outset. Now, in todays world, when exploding populations make the urban housing an ever-more pressing issue, studying failed solutions can ensure that the same mistakes arent made time after time.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Gross National Income Per Capita 2019, Atlas Method and PPPDocument4 pagesGross National Income Per Capita 2019, Atlas Method and PPPElisha WankogereNo ratings yet

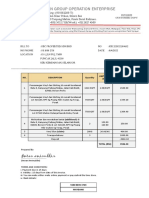

- Ilan Group Operation Enterprise: Imran AminuddinDocument1 pageIlan Group Operation Enterprise: Imran AminuddinIzhar AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Manuals PDFDocument65 pagesManuals PDFRafael NievesNo ratings yet

- Advertisement Do More Harm Than GoodDocument1 pageAdvertisement Do More Harm Than Good박성진No ratings yet

- Vernacular Architecture of Hills IndiaDocument12 pagesVernacular Architecture of Hills IndiaTushar JainNo ratings yet

- ABMM2Document3 pagesABMM2QAISER IJAZNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Bureaucracy in The PhilippDocument5 pagesThe Nature of Bureaucracy in The PhilippChristopher IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Sema V COMELEC DigestDocument5 pagesSema V COMELEC DigestTrizia VeluyaNo ratings yet

- ZTE UMTS UR15 NodeB Uplink Interference Cancellation Feature GuideDocument34 pagesZTE UMTS UR15 NodeB Uplink Interference Cancellation Feature GuideNiraj Ram ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Nix ManualDocument108 pagesNix ManualJérôme AntoineNo ratings yet

- Dinner PlateDocument29 pagesDinner PlateSABA ALINo ratings yet

- On Fedrel Mogul Goetze Training ReportDocument22 pagesOn Fedrel Mogul Goetze Training Report98960169600% (1)

- KXMB 2230 JTDocument526 pagesKXMB 2230 JTkacperorNo ratings yet

- 2024 Tutorial 8Document2 pages2024 Tutorial 8ksfksfdsfNo ratings yet

- AJM & NDT - Module - 2Document23 pagesAJM & NDT - Module - 2Naveen S BasandiNo ratings yet

- Quantitative and Qualitative Research in FinanceDocument18 pagesQuantitative and Qualitative Research in FinanceZeeshan Hyder BhattiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Decision TreesDocument12 pagesChapter 3 Decision TreesMark MagumbaNo ratings yet

- In Design: Iman BokhariDocument12 pagesIn Design: Iman Bokharimena_sky11No ratings yet

- Additive Manufacturing ProcessesDocument27 pagesAdditive Manufacturing ProcessesAizrul ShahNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal TemplateDocument2 pagesProject Proposal TemplatejorifeberdenuevoespinosaNo ratings yet

- ADS1118 Ultrasmall, Low-Power, SPI™-Compatible, 16-Bit Analog-to-Digital Converter With Internal Reference and Temperature SensorDocument47 pagesADS1118 Ultrasmall, Low-Power, SPI™-Compatible, 16-Bit Analog-to-Digital Converter With Internal Reference and Temperature SensorAdemário carvalhoNo ratings yet

- Science s4 Practical AssesmentDocument13 pagesScience s4 Practical AssesmentpotpalNo ratings yet

- Isihskipper January 2010Document25 pagesIsihskipper January 2010enelcharcoNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Exercise 1Document23 pagesLaboratory Exercise 1Paterson SoroñoNo ratings yet

- Programme Handbook 2014-15 - UG International Politics - 3Document94 pagesProgramme Handbook 2014-15 - UG International Politics - 3uannakaNo ratings yet

- Presence of Boron in Drinking Water: International Desalination Association BAH03-185Document7 pagesPresence of Boron in Drinking Water: International Desalination Association BAH03-185Jayanath Nuwan SameeraNo ratings yet

- ADR Nego PlanDocument4 pagesADR Nego PlanDeeshaNo ratings yet

- The Perfect Site GuideDocument59 pagesThe Perfect Site GuideconstantrazNo ratings yet

- GodotDocument977 pagesGodotClaudio Alberto ManquirreNo ratings yet

- Conduct Award RubricsDocument12 pagesConduct Award RubricsMark Antony M. CaseroNo ratings yet