Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Backdoor Listings: Seven Factors To Consider Before Shelling Out

Backdoor Listings: Seven Factors To Consider Before Shelling Out

Uploaded by

StradlingCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Renaissance Woman: Fat Loss, Muscle Growth & Performance Through Scientific EatingDocument20 pagesRenaissance Woman: Fat Loss, Muscle Growth & Performance Through Scientific EatingBenedict Ray Andhika33% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Professional Practice Session 1Document23 pagesProfessional Practice Session 1Dina HawashNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- E Voting SystemDocument68 pagesE Voting Systemkeisha baby100% (1)

- Remembering, Bartlett (1932)Document11 pagesRemembering, Bartlett (1932)andreea4etc100% (1)

- Client Alert - Court Enjoins Implementation of New Federal Salary Requirement For Exempt Employee StatusDocument1 pageClient Alert - Court Enjoins Implementation of New Federal Salary Requirement For Exempt Employee StatusStradlingNo ratings yet

- Client Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsDocument2 pagesClient Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsStradlingNo ratings yet

- Clients Must Vet The EDiscovery Competency of CounselDocument1 pageClients Must Vet The EDiscovery Competency of CounselStradlingNo ratings yet

- Client Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsDocument2 pagesClient Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsStradlingNo ratings yet

- Cybersecurity Legal and Practical ConsiderationsDocument1 pageCybersecurity Legal and Practical ConsiderationsStradlingNo ratings yet

- To Sell or Not To Sell? That Is The Question On The Minds of Many Board Members, Executives and InvestorsDocument1 pageTo Sell or Not To Sell? That Is The Question On The Minds of Many Board Members, Executives and InvestorsStradlingNo ratings yet

- The Perfect PitchDocument3 pagesThe Perfect PitchStradlingNo ratings yet

- Client Alert - Preparing For California's New Paid Sick Leave LawDocument2 pagesClient Alert - Preparing For California's New Paid Sick Leave LawStradlingNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Use Provisions - Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Retail Lease AgreementsDocument6 pagesExclusive Use Provisions - Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Retail Lease AgreementsStradling100% (1)

- Client Alert - California To Guarantee Paid Sick LeaveDocument2 pagesClient Alert - California To Guarantee Paid Sick LeaveStradlingNo ratings yet

- English Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesDocument18 pagesEnglish Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesLanping FuNo ratings yet

- Schedule CDocument273 pagesSchedule CAzi PaybarahNo ratings yet

- Stones Unit 2bDocument11 pagesStones Unit 2bJamal Al-deenNo ratings yet

- Desmand Whitson Resume 1PDFDocument2 pagesDesmand Whitson Resume 1PDFRed RaptureNo ratings yet

- Manual PDFDocument3 pagesManual PDFDiego FernandezNo ratings yet

- If ملخص قواعدDocument2 pagesIf ملخص قواعدAhmed GaninyNo ratings yet

- The Child and Adolescent LearnersDocument12 pagesThe Child and Adolescent LearnersGlen ManatadNo ratings yet

- Operational Framework of Community Organizing ProcessDocument18 pagesOperational Framework of Community Organizing ProcessJan Paul Salud LugtuNo ratings yet

- Reply of DV ComplaintDocument17 pagesReply of DV Complaintparveensaini2146No ratings yet

- Year 8 English: Examination - Semester 2, 2017 EXAM BookletDocument23 pagesYear 8 English: Examination - Semester 2, 2017 EXAM BookletJayaletchumi Moorthy100% (1)

- The Last LessonDocument31 pagesThe Last LessonKanika100% (1)

- Logging Best Practices Guide PDFDocument12 pagesLogging Best Practices Guide PDFbnanduriNo ratings yet

- p-37 Recovery of Gold From Its OresDocument33 pagesp-37 Recovery of Gold From Its OresRussell Hartill100% (6)

- Computer Awareness Topic Wise - TerminologiesDocument15 pagesComputer Awareness Topic Wise - TerminologiesdhirajNo ratings yet

- View AnswerDocument112 pagesView Answershiv anantaNo ratings yet

- Question Bank FormatDocument5 pagesQuestion Bank Formatmahidpr18No ratings yet

- Veterinary MicrobiologyDocument206 pagesVeterinary MicrobiologyHomosapienNo ratings yet

- Absorption Costing PDFDocument10 pagesAbsorption Costing PDFAnonymous leF4GPYNo ratings yet

- BProfile EnglishDocument3 pagesBProfile EnglishFaraz Ahmed WaseemNo ratings yet

- Goldilocks and The Three Bears Model Text 2Document5 pagesGoldilocks and The Three Bears Model Text 2api-407594542No ratings yet

- Loi Bayanihan PCR ReviewerDocument15 pagesLoi Bayanihan PCR Reviewerailexcj20No ratings yet

- Talent Acquisition Request Form: EducationDocument1 pageTalent Acquisition Request Form: EducationdasfortNo ratings yet

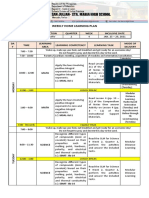

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateDocument3 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateMarvin Yebes ArceNo ratings yet

- Answer KeyDocument21 pagesAnswer KeyJunem S. Beli-otNo ratings yet

- Year3 GL Style Maths Practice Paper PrintableDocument4 pagesYear3 GL Style Maths Practice Paper PrintableLolo ImgNo ratings yet

- Bac 1624 - ObeDocument4 pagesBac 1624 - ObeAmiee Laa PulokNo ratings yet

Backdoor Listings: Seven Factors To Consider Before Shelling Out

Backdoor Listings: Seven Factors To Consider Before Shelling Out

Uploaded by

StradlingOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Backdoor Listings: Seven Factors To Consider Before Shelling Out

Backdoor Listings: Seven Factors To Consider Before Shelling Out

Uploaded by

StradlingCopyright:

Available Formats

B-44 ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL

LAW SPECIALTIES Advertising Supplement

NOVEMBER 21, 2011

Ba ckdoor Li sti ngs: Se ve n F a ctors to Consi de r Be fore She l l i ng Out

n Unhappy Tale Once upon a time, the president of a promising early-stage private company called NaiveBiz, Inc. received an unsolicited telephone call. The caller, claiming to be a small-business consultant, asked the president if he was interested in learning how his company could quickly and lucratively tap the public equity markets. Skeptical but curious, the president allowed the caller to continue. You can take NaiveBiz public for far less than the cost of the average IPO, the consultant amiably explained, and more quickly, too. The secret is not really a secret at all. Hundreds of companies like yours have done it. How? By merging with a public shell. Well began the president. Lets talk over lunch, the consultant offered. My treat. As drinks arrived a few days later, the consultant elaborated on the proposed deal. He called the transaction a reverse merger or a backdoor listing, and he was quick to spin the benefits: investor visibility, capital-market access, stock-based acquisition opportunities. He also listed past successes: Occidental Petroleum, Turner Broadcasting, Texas Instruments. Finally, alongside dessert, the consultant unveiled a hedge fund called PredatorFund willing to invest $2.5 million in the deal in exchange for a 10 percent stake in the company. PredatorFund promised another cash infusion via warrants for $2 million in additional stock at the market price existing as of the date of exercise of the warrants. The presidents spoon hesitated in midair. Two and a half, you say? That could make a big difference. The consultant agreed. Both men smiled. Within a few months, the presidents grin had hardened. To his chagrin, transaction costs had whittled away PredatorFunds overall investment. The owners of the public shell demanded $400,000. Attorneys and accountants, both selected by PredatorFund, cost nearly as much. A handful of other charges including, of course, a hefty promoters fee paid to the consultant and an advisory fee paid to PredatorFund shaved off another few hundred grand. By the time the deal closed, the president saw only $1.5 million extra in NaiveBizs coffers. While $2.5 million would have been sufficient for NaiveBiz to execute its strategic vision, $1.5 million plainly was not enough. However, PredatorFund refused to exercise its warrants. When the president tried to find other sources of funding, he found that NaiveBiz could not go to the public markets for capital because it had not generated any analyst coverage or other investor interest. No venture capital firms or other possible investors would even consider investing in NaiveBiz because of PredatorFunds large stock position and unexercised warrants. Still, NaiveBiz did the best it could with what it had. When NaiveBiz announced that a large customer had quadrupled its orders, the markets took notice. The volume of trades in NaiveBizs stock tripled, and the stock price increased from $0.45 to $0.87. The president was encouraged, believing this recent attention may create opportunities to raise much-needed capital. However, seeing an opportunity to make some money from NaiveBizs increased stock price, PredatorFund chose that moment to dump as much of its stock as the public markets could absorb. As a result, NaiveBizs stock price dropped to $.15. Then, taking advantage of the stock price drop it caused, PredatorFund promptly exercised its warrants and obtained many more shares than it would have when the market price had been higher. All at once, PredatorFund owned a majority of the business. PredatorFund now had new plans for NaiveBiz and they did not involve the president. by Marc Schneider and Mark Skaist, Shareholders, Stradling Yocca Carlson & Rauth

A little boardroom maneuvering was all it took to show the president the door. The story above, based on actual events, illustrates the perilous nature of reverse mergers into public shells, aka backdoor listings, especially when companies fail to consider their long-term goals. Unfortunately, the risks and rewards of backdoor listings can be hard to discern, making such long-term calculations difficult. To provide some guidance, this article: (1) describes the mechanics of a typical reverse merger; (2) summarizes the regulatory environment; and (3) assesses the commonly purported benefits of reverse-mergers, particularly in light of changing regulations.

Merger Mechanics Although a handful of large, well-known companies have gone public via reverse merger into a public shell, the vast majority of these transactions involve relatively unknown small and mid-sized firms. For many businesses, the process starts with a promoters pitch. If a company concludes that a reverse merger serves its interests, then the associated promoter will often act as dealmaker, initially helping to locate a suitable public shell company. By definition, a shell company has few or no assets or operations, but its stock is publicly held or it is otherwise already subject to the reporting requirements of the Exchange Act. Shells may be remnants of erstwhile corporations, or they may have been formed specifically for the purpose of taking an operating company public. Either way, they do not come cheap. Before the 2008 economic downturn, the most attractive shells sold for $300,000 to $400,000 in cash, plus $600,000 to $700,000 in equity, although prices have since dropped significantly. After locating a public shell, the parties merge the private firm into the shell or its subsidiary. This usually results in the shareholders of the private company owning a majority interest in the newly-combined public corporation, which in turn holds the assets of the original private firm. Of course, like the shell, the newly-merged company remains subject to all state and federal securities laws. Among other obligations, this means that the company must promptly file certain initial disclosures with the SEC, as well as subsequent regular reports. The Regulatory Environment Reverse mergers into public shells are not inherently problematic. However, a series of pump-and-dump and similar scams in the 1970s and 1980s tainted these deals for many observers. Such abuses prompted several rounds of legislation, rule-making and enforcement that nearly ground reverse-merger activity to a halt by the mid-1990s. The dot-com bust and the weak IPO market of the 2000s led to renewed interest in reverse mergers. According to reports, the total number of backdoor listings onto U.S. markets jumped from 46 in 2000 to nearly 250 ten years later. Likely wary of this growth, the SEC in 2005 adopted additional rules to discourage fraud. Among other restrictions, these rules (1) prohibit shell companies from using Form S-8 (securities registered on Form S-8 are immediately effective) and (2) obligate companies that go public by reverse merger to make extensive disclosures within four days of the merger (instead of the 71 days previously allowed). Still, deceptive practices continue. Within the last year, investigators have uncovered numerous accounting irregularities at dozens of China-based reverse-merger firms, leading regulators to suspend trading in several companies and to delist others entirely. The established organizations across a wide range of industries. The firm has built its practice around its clients core needs. Stradlings size, structure and culture allow it to provide big-firm representation with small-firm flexibility and responsiveness. Today Stradling serves established and emerging companies, and global organizations using that very premise. For more information visit www.sycr.com

Stradling represents companies and entities which seek a sophisticated law firm with experienced counsel to guide critical transactions and disputes. Originally founded in 1975 to represent Southern Californias most innovative emerging growth companies, Stradling is known today as a leading full-service law firm representing high growth and

About Stradling

Newport Beach 660 Newport Center Drive Suite 1600 Newport Beach, CA 92660 Phone (949) 725-4000

Sacramento 500 Capitol Mall Suite 1120 Sacramento, California 95814

San Diego 4365 Executive Drive Suite 1500 San Diego, CA 92121

NOVEMBER 21, 2011

LAW SPECIALTIES Advertising Supplement

ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL B-45

Benefits and Costs Why do reverse mergers hold appeal? Advocates of backdoor listings typically list a number of benefits. Yet as discussed below, many of these purported advantages are not so clear-cut. (1) Speed According to a 2006 study published in the Reverse Merger Report, backdoor listings take an average of 92 days to complete, compared to 287 days for a typical IPO. Since then, the regulatory environment has tightened significantly, and it promises to become more stringent. As a result, this speed advantage may be overstated. On the other hand, the IPO process is purposefully lengthy. It takes time for a company to implement the compliance infrastructure necessary to impress the public markets, and reputable underwriters will not take a company public until this infrastructure is in place. (2) Cost Reverse mergers often cost less than IPOs, but much of these savings may result from cost shifting. Unlike the typical reverse merger, for instance, an IPO usually includes a public road show aimed at building an investor following. Skipping this marketing saves money, but it may also cause a reverse-merger company to languish in anonymity down the road. Other up-front savings may come at the expense of essential due diligence, especially where the public shell is a former operating company with hidden or contingent liabilities. (3) Dilution Compared to IPOs, reverse mergers typically leave insiders with a slightly larger ownership percentage, at least at first. As noted below, however, reverse mergers do not include a built-in cash-raising component, and they frequently fail to generate a broad and active trading market. Accordingly, these companies often need concurrent or subsequent outside funding, which may necessitate additional shareholder dilution. (4) Financing The oft-touted availability of PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity) funding recasts perhaps the major shortcoming of reverse mergers (i.e., no built-in financing) as an opportunity to invite private-equity or hedge fund money into the process. Of course, such investment, if available, comes at the cost of ownership participation and other accommodations. Yet without such funding, reverse-merger firms that need to raise capital must rely entirely on subsequent public investment and share appreciation sometimes dicey propositions. (5) Liquidity Reverse-merger promoters also point to conventional benefits of being public, like enhanced liquidity. Backdoor listings do not necessarily lead to marked or immediate liquidity improvement, however. For example, the SEC now requires shell promoters and founders to wait 12 months before selling shares on the open market, unless the parties register the sale. More importantly, liquidity depends on public interest, and this may never materialize. A recent study by Mirus Capital Advisors suggests that a majority of reversemerger firms effectively become publicly traded private companies with small market capitalizations, single digit or lower share prices, and little or no visibility in the investment community. (6) Visibility Another general benefit reverse-merger advocates tout is increased market visibility. Yet most reverse-merger firms do not trade on major exchanges. Instead, they appear on the OTC Bulletin Board or the Pink Sheets, where analyst coverage is scarce. Moreover, gaining access to the major exchanges is not easy. NASDAQ, for instance, requires reversemerger firms to file new listing applications even if the pre-merger public entity was already listed. As noted above, recently announced regulatory changes make this process even more difficult (e.g., by requiring a seasoning period and requiring a sustained period of maintaining a minimum trading price before listing). As a result, many reverse-merger firms fail to garner much market attention. In the past, this enabled unscrupulous promoters to escape detection as they controlled a companys public float, manipulated the price higher, and then sold, leaving the company with a precipitous drop in share price and possible liabilities.

SEC has also initiated several enforcement actions against reverse-merger companies and promoters while warning public investors of possible fraud and abuse. Meanwhile, NASDAQ, NYSE Amex Equities, formerly known as the American Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange just announced stricter listing requirements for reverse-merger firms. Among other requirements, these new rules require a one-year seasoning period before most of these companies would be eligible to list. In addition, most of these companies must maintain the requisite minimum share price for a sustained period, and for at least 30 of the 60 trading days, immediately prior to its listing application and the exchanges decision to list.

Recommendations Explore all financing sources: Given the inherent risks associated with reverse mergers into a public shell, companies should make sure that they have adequately explored all their potential financing options. Companies should not consider a backdoor listing as an alternative to an angel or venture capital financing. Unlike those other types of financings, a company that merges with a public shell will be subject to the reporting requirements of the U.S. securities laws, which are expensive and burdensome. Just because a company tried, but was unable, to raise funds through angel investors or venture capitalists is no reason to opt for a backdoor listing (in fact, if a company isnt ready for a private financing, then it likely should not avail itself of the public markets). Conduct thorough background checks. Both promoter and investor will play important roles in any reverse merger, and in the company going forward. Before executing any agreements, companies must make sure to use all publicly available sources to learn about them. Companies should require references and interview those references about their experiences with the reverse merger process, including how the company has fared post-merger into the public shell. Retain independent, experienced attorneys. Under no circumstances should companies accept counsel recommended by the investor or promoter. Retaining independent counsel is critical. Counsel will exhaustively vet the public shell and the other parties to the deal. In addition, knowledgeable counsel will minimize the possibility of a loss-of-control event and may be able to negotiate for ongoing financing guarantees. Marc Schneider is a Shareholder in the Newport Beach office of Stradling where he practices securities and complex business litigation. Mr. Schneider has handled complex business litigation in federal and state courts throughout the country. He has significant securities litigation experience, including successfully defending companies, private equity and venture capital firms, directors, and officers, against SEC and other government investigations and class action, derivative, and merger and acquisition litigation. He also has particular expertise in antitrust, False Claims Act, and data breach matters. In addition to his litigation practice, Mr. Schneider also serves as the firms General Counsel. mschneider@sycr.com / 949.725.4000 Mark L. Skaist is a shareholder in the Newport Beach office of Stradling. He serves as assistant chairman of the Corporate Department and is a member of the Executive Committee. He practices corporate and securities law, focusing on public and private securities offerings, venture capital transactions, mergers and acquisitions and intellectual property transactions (including technology and content licensing, development and distribution transactions), primarily in the high technology and information technology industries. His clients include leading private and public companies involved in network infrastructure technology, telecommunications, software, new media, clean tech and apparel/action sports. mskaist@sycr.com / 949.725.4000

(7) Success Last but not least, companies must consider how successful any potential backdoor listing will ultimately be. Reverse-merger promoters readily point to some well-known success stories, including Occidental Petroleum, Turner Broadcasting Systems and others. Unfortunately, empirical evidence indicates that such successes are rare. The Mirus study reported that a majority of companies that go public through the shortcut of the reverse merger are substantially worse off after the process. Other investigations reached similar conclusions. A 2005 study published in the Journal of Corporate Finance, for instance, found that reverse-merger firms are small, unprofitable and likely to fail within two years of going public. Further, finance professors at Iowa State determined in 2010 that nearly 90 percent of reverse-merger firms see stock-price declines a year after the merger while less than 10 percent experience positive long-run buy-and-hold returns.

Marc Schneider

Mark L. Skaist

San Francisco 44 Montgomery Street Suite 4200 San Francisco, CA 94104-4803

Santa Barbara 800 Anacapa Street Suite A Santa Barbara, CA 93101

Santa Monica 100 Wilshire Boulevard Suite 440 Santa Monica, CA 90401

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Renaissance Woman: Fat Loss, Muscle Growth & Performance Through Scientific EatingDocument20 pagesRenaissance Woman: Fat Loss, Muscle Growth & Performance Through Scientific EatingBenedict Ray Andhika33% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Professional Practice Session 1Document23 pagesProfessional Practice Session 1Dina HawashNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- E Voting SystemDocument68 pagesE Voting Systemkeisha baby100% (1)

- Remembering, Bartlett (1932)Document11 pagesRemembering, Bartlett (1932)andreea4etc100% (1)

- Client Alert - Court Enjoins Implementation of New Federal Salary Requirement For Exempt Employee StatusDocument1 pageClient Alert - Court Enjoins Implementation of New Federal Salary Requirement For Exempt Employee StatusStradlingNo ratings yet

- Client Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsDocument2 pagesClient Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsStradlingNo ratings yet

- Clients Must Vet The EDiscovery Competency of CounselDocument1 pageClients Must Vet The EDiscovery Competency of CounselStradlingNo ratings yet

- Client Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsDocument2 pagesClient Alert - New Federal Statute Protecting Trade SecretsStradlingNo ratings yet

- Cybersecurity Legal and Practical ConsiderationsDocument1 pageCybersecurity Legal and Practical ConsiderationsStradlingNo ratings yet

- To Sell or Not To Sell? That Is The Question On The Minds of Many Board Members, Executives and InvestorsDocument1 pageTo Sell or Not To Sell? That Is The Question On The Minds of Many Board Members, Executives and InvestorsStradlingNo ratings yet

- The Perfect PitchDocument3 pagesThe Perfect PitchStradlingNo ratings yet

- Client Alert - Preparing For California's New Paid Sick Leave LawDocument2 pagesClient Alert - Preparing For California's New Paid Sick Leave LawStradlingNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Use Provisions - Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Retail Lease AgreementsDocument6 pagesExclusive Use Provisions - Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Retail Lease AgreementsStradling100% (1)

- Client Alert - California To Guarantee Paid Sick LeaveDocument2 pagesClient Alert - California To Guarantee Paid Sick LeaveStradlingNo ratings yet

- English Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesDocument18 pagesEnglish Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesLanping FuNo ratings yet

- Schedule CDocument273 pagesSchedule CAzi PaybarahNo ratings yet

- Stones Unit 2bDocument11 pagesStones Unit 2bJamal Al-deenNo ratings yet

- Desmand Whitson Resume 1PDFDocument2 pagesDesmand Whitson Resume 1PDFRed RaptureNo ratings yet

- Manual PDFDocument3 pagesManual PDFDiego FernandezNo ratings yet

- If ملخص قواعدDocument2 pagesIf ملخص قواعدAhmed GaninyNo ratings yet

- The Child and Adolescent LearnersDocument12 pagesThe Child and Adolescent LearnersGlen ManatadNo ratings yet

- Operational Framework of Community Organizing ProcessDocument18 pagesOperational Framework of Community Organizing ProcessJan Paul Salud LugtuNo ratings yet

- Reply of DV ComplaintDocument17 pagesReply of DV Complaintparveensaini2146No ratings yet

- Year 8 English: Examination - Semester 2, 2017 EXAM BookletDocument23 pagesYear 8 English: Examination - Semester 2, 2017 EXAM BookletJayaletchumi Moorthy100% (1)

- The Last LessonDocument31 pagesThe Last LessonKanika100% (1)

- Logging Best Practices Guide PDFDocument12 pagesLogging Best Practices Guide PDFbnanduriNo ratings yet

- p-37 Recovery of Gold From Its OresDocument33 pagesp-37 Recovery of Gold From Its OresRussell Hartill100% (6)

- Computer Awareness Topic Wise - TerminologiesDocument15 pagesComputer Awareness Topic Wise - TerminologiesdhirajNo ratings yet

- View AnswerDocument112 pagesView Answershiv anantaNo ratings yet

- Question Bank FormatDocument5 pagesQuestion Bank Formatmahidpr18No ratings yet

- Veterinary MicrobiologyDocument206 pagesVeterinary MicrobiologyHomosapienNo ratings yet

- Absorption Costing PDFDocument10 pagesAbsorption Costing PDFAnonymous leF4GPYNo ratings yet

- BProfile EnglishDocument3 pagesBProfile EnglishFaraz Ahmed WaseemNo ratings yet

- Goldilocks and The Three Bears Model Text 2Document5 pagesGoldilocks and The Three Bears Model Text 2api-407594542No ratings yet

- Loi Bayanihan PCR ReviewerDocument15 pagesLoi Bayanihan PCR Reviewerailexcj20No ratings yet

- Talent Acquisition Request Form: EducationDocument1 pageTalent Acquisition Request Form: EducationdasfortNo ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateDocument3 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateMarvin Yebes ArceNo ratings yet

- Answer KeyDocument21 pagesAnswer KeyJunem S. Beli-otNo ratings yet

- Year3 GL Style Maths Practice Paper PrintableDocument4 pagesYear3 GL Style Maths Practice Paper PrintableLolo ImgNo ratings yet

- Bac 1624 - ObeDocument4 pagesBac 1624 - ObeAmiee Laa PulokNo ratings yet