Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Andrew Carnegie Biography PDF

Andrew Carnegie Biography PDF

Uploaded by

Oluwole Jedidiah OlusolaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Andrew Carnegie Biography PDF

Andrew Carnegie Biography PDF

Uploaded by

Oluwole Jedidiah OlusolaCopyright:

Available Formats

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie was one of America's most successful businessmen, he fou nded Carnegie Steel Company which later became U.S. Steel. At age 33, An drew had an annual income of $50,000 which he made no effort to increase but spend the surplus on charitable cause. Carnegie was born on the 25th of November 1835 in Dunfermline, Scotland, t o William and magaret Carnegie. His father William was a weaver who made f ine damask linen with elaborate designs. The rapid industrialization of th e textile industry in Britain, affected the trade of handloom weavers like Williams. Which made him sold the last of their looms and sailed for the United States. They settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsb urgh Andrew started earning money at the age of 13 when he went to work as a bob bin boy in a cotton mill, earning $1.20 per week while he attends night sch ool across the river in Pittsburgh. He moved out of the cotton factory in 1 849 to become a messenger in a Pittsburgh telegraph office. Carnegie delive red messages to all the important businesses in the city and soon knew a gr eat deal about Pittsburghs commercial affairs. He also came to appreciate the importance of the telegraph to the new economy that was then emerging. This afforded him the opportunity to learn telegraphy (which he taught hims elf) Andrews passion for self-development was enhanced by Colonel James Anders on, who gave him access to his personal library of 400 volumes every Satur day night. From then on, opportunity started presenting themselves to him. He was hired by the Pennsylvania Railroad as private secretary to Thomas Alexander Scott (the railroad official), his earning then was 35$ per mon th. Andrew got this job as a result of his reputation as the best telegrap h operator in town and Scott needed a personal telegrapher and secretary. He was promoted many times and in 1859 became the superintendent of the Pittsburgh division of the railroad at the age of 24!, when Scott became g eneral superintendent of the line.

Carnegie soon became Scotts right hand man and was awarded with greater an d greater responsibilities. Carnegie appointment as the Superintendent of the Pittsburgh Division was the most important and difficult Division of th e railroad and Carnegie did an outstanding job. Indeed, Carnegie was so goo d that if he had chosen to make a career of it he would have been an import ant Railroad President in his own right. Carnegie showed his abilities by p erfecting the system of statistical control even further and introducing ma nagement innovations. He ordered the telegraph stations be kept open 24 hou rs a day and appointed night time dispatchers thereby greatly increasing th e efficiency of 24 hour movements of traffic. To clear away wrecks more qui ckly he ordered the cars blocking the track to be burned and he even had te mporary tracks laid around wrecks to put the railroad back in service more quickly. The genesis of Andrew carnegies interest in investment started when Scott persuaded him in 1856 to buy some stock and even loaned him the money to do so. Carnegie bought the stock primarily because he admired Scott and re garded him as a father figure. The experience of receiving dividends chang ed Carnegies attitude and he became an enthusiastic investor. He thereafter, partnered an inventor Mr Woodruff, by investing in his proje ct. Woodruff's invention was the sleeping car. The great distances transver sed by railways had meant stopping for the night at hotels and inns by the railside, so that passengers could rest. The sleeping car sped up travel an d helped Americans settle the American West. The investment proved a great success and a source of great fortune for Woodruff and Carnegie. Carnegie proceeded to increase his wealth through careful investments. In 1864, Carnegie invested US$40,000 in Storey Farm on Oil Creek in Venango C ounty, Pennsylvania. In one year, the farm yielded over US$1,000,000 in ca sh dividends, and petroleum from oil wells on the property sold profitably . Carnegie was subsequently associated with others in establishing a steel rolling mill.

Carnegie quit the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1865 both to concentrate on the bridge business which he was confident would boom after the War (the transc ontinentals and rebuilding the railroads in the South) and to pursue invest ments. Keystone landed several major contracts to build bridges across the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Typically, major bridges were built by ind ependent companies that floated stock to pay for the construction and then the bridge itself would be leased to a railroad. In addition, sometimes the bridge company contracted with a separate construction company to actually

build the bridge. This opened even more avenues for profitability in secur ities transactions as the construction company usually was paid in stock at an inflated rate. This paved the way for multiple commissions for Carnegie in his role as securities salesman In 1867 Carnegie moved from Pittsburgh to New York City and began travelli ng regularly to Europe to sell bonds. By 1869 Carnegie and his perennial p artners Scott and Thomson had made small fortunes by starting up their own telegraph company (which conveniently used the PARR right-of-way and had contracts with the PARR) which Carnegie was later able to quietly sell at a big profit. The trio also made an alliance with Pullman to provide the U nion Pacific Railroad with sleeping cars. In 1871 the same group arranged a $600,000 loan to the Union Pacific in exchange for UP stock. The stock p romptly rose because investors thought Thomson who ran "the standard rai lroad of the world" would take over the UP management. Instead, Carnegie began selling their "cheap" UP stock at a substantial profit. In 1869 Carnegie met Junius Morgan (J. P. Morgans father) in London. Juni us Morgan was one of the leading investment bankers in London and his word "was as good as gold". If Morgan endorsed a bond issue, it would be easil y placed. Carnegie made substantial fees (typically 2.5%) selling bonds in Europe. He placed issues for various bridge construction projects and sev eral railroads. By 1872 he was a rich man. Iron: 1861 - 1872 Carnegie had gone into the iron business as early as 1861 when he and Tho mas Miller had made an investment in a local iron company. Carnegie and M iller and two other partners later founded the Cyclops Iron Works in Pitt sburgh in October of 1864. This firm was later merged with another firm i n 1865 to form the Union Iron Works. After buying Miller out (at Millers request), Carnegies partners were his brother Tom, Henry Phipps, and An drew and Anthony Kloman Carnegies aim was to ensure his Keystone Bridge Company a reliable and che ap supply of iron beams and plates -- in short, vertical integration. This was something new in the iron business. Before Carnegie the business was hi ghly specialized one mill produced the pig iron; another converted the pi g iron to bars and slabs; other mills then rolled railroad iron, manufactur ed plates, nails, and so on. Transferring the iron from one establishment t o another significantly slowed down the production of finished goods and ad ded to the costs because of all the middlemen. His training on the Pennsylv ania railroad was crucial. With the high fixed costs of railroading, to mak e money it was essential to: 1) have a good cost accounting system; and 2) once the costs were known, speed the flow of traffic through the system and

increase its volume. His great innovation was applying these principles to the iron and steel business. After some initial resistance, Carnegie was able to impose a rigorous cost a ccounting system which including installing weighing scales at all points in the mills to see where material was saved or not saved, and every man in a particular job was compared with all other men in that job. Cost accounting was the most important factor thereafter in personnel, marketing, and invest ment decisions. In terms of speeding up the flow and increasing the volume, combining the p roduction of iron beams and plates with the bridge company, he drastically cut the time and labor required to move material from operation to operatio n. When Carnegie felt that he had successfully blended the two businesses he mo ved to expand further. In 1870 he built his own blast furnace (called the "L ucy" after Tom Carnegies wife) to guarantee supplies of pig iron that he co ntrolled. The furnace went into blast in 1872 and Carnegie was determined to increase its efficiency. He was amazed when he first went into the iron bus iness that the owners of blast furnaces knew very little about what went on inside the furnace. It was literally a "seat-of-the pants" "rule-of-thumb" o peration. Now that he owned his own blast furnace Carnegie hired a German chemist to find out what was going on within the furnace. His chemist was able to tell him how good his iron ore was and how to improve the charge in the furnace . Andrew Kloman figured out a way to remove the slag from the furnace more rapidly thereby increasing the output. With the cost accounting system, Car negie and his associates soon realized that they could hard drive the furna ce. Hard Driving (increasing the flow of hot air through the bottom of the furnace at high pressure) wore out the furnace lining very rapidly, but the increased output more than justified the relining costs and the reduced li fe of the furnace. Indeed, Peter Berck ("Hard Driving and Efficiency: Iron Production in 1890") shows that in 1890 "the pure profits of a hard-driven furnace would be enough to pay for the furnace in two years!" An American s tyle hard driven furnace had to be relined every 3 years as opposed to 12 y ears for a British style furnace. Even with the cheaper capital available i n Britain, the increased output of an American style hard driven furnace pr oduced capital savings if output exceeded the (low) figure of 45,000 tons a year. Carnegies men eventually got the Lucy to produce 100,000 tons a year! In 1872 Carnegie came back from a trip to England convinced that the future was steel. Because of his experience on the Pennsylvania railroad, Carnegi e was convinced beyond any shadow of doubt that the American railroad syste

m had to switch to steel rails as soon as they were cheaply available. The difference in strength and longevity was on the order of a factor of 15 to 20. The productivity gains to be had were so great that it was simply a mat ter of time before the railroads switched over. Indeed, as early as 1865 Carnegie had experimented with variety of hybrid ir on-steel rails but all these experiments failed. In 1866 the rival claimants to the Bessemer steel process had compromised their differences thereby mak ing the patents available for licensing in the U.S. The Bessemer process suc cessfully burned out the silicon and the carbon from the pig iron thereby making the cheap production of steel practical but it did not burn out the phosphorus. Consequently, for the process to work, iron ore very low in pho sphorus had to be used. Such high quality iron ore lay in abundance in the Upper Peninsula of Michig an. It was discovered in 1845 and its exploitation made possible with the co nstruction of the canal at Sault Ste. Marie in 1855. However, it was not unt il 1868 that the ore was tested for its phosphorus content and its usefulnes s in the Bessemer steel process determined. And it was not until 1870-71 tha t the transportation facilities were good enough to funnel large quantities of the ore down to the lower Great Lakes. Given all these facts, it is not surprising that during his tour of the Bes semer plants in England during 1872 Carnegie determined that simply expandi ng his existing iron mills was too limited a venture. He decided he had to build a brand new, large plant devoted solely to making Bessemer steel rail road rails. This was to be The Edgar Thomson Works. Henry Phipps and Tom Carnegie declined at first to participate in Andrew C arnegies "daring" new venture and Carnegie was forced to set up a separat e partnership to build the new works. He was able to persuade a number of influential Pittsburgh businessmen to participate and he put up $250,000 o f the total $700,000 capitalization of the venture himself and his old par tners from Union Iron -- Phipps, Tom Carnegie, and Kloman each chipped in $50,000 apiece. His old allies Tom Scott and J. Edgar Thomson also came in for small amounts via Carnegies share. Land was acquired at the site of Braddocks field on the Monongahela River. (This was the battlefield where the British General Braddock was defeated and killed during the French-In dian War. One of his officers, Col. George Washington, led the retreat tak ing the troops to the south towards Maryland.) The location was ideal beca use it was near two railroads the B&O and the Pennsylvania and it was near the Youghiogheny River which ran through the nearby coal regions. To supervise the construction Carnegie hired Alexander L. Holley who had a contract with Bessemer for the exclusive use of his process in America. H olley already had built several Bessemer plants and had made considerable improvements in the process. Carnegie paid only $11,000 in patent fees and

a $5000 fee to Bessemer (and a $2,500 per year salary) to construct the w orks. Shortly after construction was started the financial Panic of 1873 began t hat September and the country was plunged into depression. Some of his par tners were unable to come up with their shares in the project and Carnegie himself was pressured by Tom Scott to help bail him out of his problems w ith the Texas & Pacific Railroad. Carnegie wisely refused, Scott went bank rupt, and their friendship ended. To keep the enterprise afloat Carnegie t ook Holley with him to London in the summer of 1874 and the two were, with the aid of Junius Morgan, able to sell $400,000 worth of bonds to London investors. The Edgar Thomson works were completed in 1875 and the business was an im mediate success. Carnegie was very fortunate that Holley recruited Captai n William Jones from the Cambria Iron Works in Johnston to help run the n ew mill as the superintendent at the beginning of the project. Jones in t urn recruited many talented men and it was Jones and his Lieutenants that made the works such a smashing success. Jones had worked closely with Holley and was an expert iron and Bessemer s teel man. He introduced many improvements in the mill and was a fiercely c ompetitive man. He enjoyed a challenge and his personality meshed perfectl y with Carnegies obsession with costs and the speed of production. Jones was a mechanical genius and made numerous improvements to the mill. He inv ented many important processes and devices to speed the flow of the metal through the various stages of the production process before it cooled. Thi s resulted in huge savings and increased output because the metal did not have to be re-heated at the various stages of processing. For example, he invented the Jones mixer, a giant "tea kettle like" box that could hold up to 150 tons of molten pig iron fresh from the blast furnace a nd later transfer it to the Bessemer converter. He also shared Carnegies ba sic philosophy of always using the best tools for the purpose at hand and ev en if a tool or machine was not worn out it was to be discarded in favor of a better one if that was cost efficient. Finally, the workers in the plant r espected Jones and he often argued for their interests when he felt that Car negie made unrealistic demands for reductions in labor costs. Nevertheless, Jones worked his men hard 12 hour days seven days a week with only the 4th of July off. Because Carnegie always had majority control in the partnership, he insiste d upon plowing almost all the profits back into improving the works alway s upgrading, always in search of the littlest efficiencies. He was always c oncerned more with building and improving than spending dividends. Carnegie liked to promote from within. If he found a particularly outstanding young man in his works he would offer to make him a partner (at a fraction of 1%

but that was still worth a lot of money). The other side of the coin was C arnegies ruthlessness when it came to partners he felt were no longer perf orming to his standards. Those men were forced out of the partnership and b y the "iron-clad" partnership agreement they had to cash in their shares at the "book" value. Since the partnership was grossly undervalued this meant that the man forced out would walk away with a fraction of the true value of his share of the firm. Carnegie became the chief salesman. Here his experiences working on the Pen nsylvania railroad and selling bonds meshed perfectly. He knew most of the railroad leaders in the United States and worked in his usual tireless fash ion to sell them his Bessemer steel rails. As a consequence, the output of the Edgar Thomson Works steadily rose from 21,674 tons in 1875 to 536,838 t ons in 1889. During the same period his costs fell from $58 to $25 a ton wi th the profits rising accordingly. In October 1883 Carnegie bought the Homestead Works from a group of Pittsb urgh investors. It was a highly efficient steel rail works but it had been plagued with labor troubles for some years. Carnegie expanded the plant a nd installed large new open hearth furnaces and by 1885 converted Homestea d to rolling beams and angles in order to diversify his products. In 1886 Carnegie on Jones recommendation made Charles Schwab (at the age of 2 4) general superintendent of the Homestead Works. In October 1886 Thomas Carnegie died of alcoholism. Tom Carnegie was an u nhappy man who had lived his whole life in Andrews shadow "minding the s tore" for his great brother. By this time Andrew Carnegie was traveling f or pleasure and taking long vacations. In addition he was engaged to be m arried and finally did marry the next year. He relied on the cost sheets that were provided to him no matter where he was to oversee his holdings. However, the sheer size and complexity of the business meant that he had to have high quality managers at each of his works and he increasingly f elt the need to have a single top manager to oversee all the mills. He so lved his problem temporarily by making Henry Phipps the head of Carnegie Brothers Company (which was separate from Carnegie, Phipps Company, Limit ed) and by bringing Henry Clay Frick into the partnership. Carnegie had purchased an interest in Fricks Coke company in 1881 and by 1 883 Carnegie Brothers controlled a majority of the Frick Coke Company stock . Carnegie wanted to ensure himself a guaranteed supply of high quality cok e and did so by his usual route vertical integration. The Frick coke was from the Connelsville region southeast of Pittsburgh and was of unusually h igh quality. (Connelsville coal was high grade, soft, and easily worked. It was very low in ash and sulfur and when it was turned into coke it was a f ine, hard, dense fuel.) Carnegie admired Fricks abilities and after 1886 h e needed Fricks help with the management of his vast steel interests.

Frick became head of Carnegie Brothers in January 1889 after an initial fa lling out with Carnegie over the handling of a strike in the Coke fields i n 1887. Frick eventually was coaxed back into the active management and wi th Henry Phipps request to withdraw from active management and the death of David Stewart Phipps successor the way was cleared for Frick. Frick was an immediate and huge success. Profits rose from $2 million in 1888 t o $3.5 million in 1889 to $5.4 million in 1890. In November 1890 Frick was able to buy the Allegheny Bessemer Steel Compan y located in Duquesne south of the Edgar Thomson Works. The Duquesne Works were superior to the Carnegie mills in that the ingots were rolled into f inished steel railroad rails with no reheating. The Carnegie people had di sparaged the process implying that it produced defective rails. After gain ing control of the works, a careful cost analysis persuaded Carnegie, Fric k, and all the top managers that the Duquesne direct rolling process was i ndeed superior to the method they were using. Accordingly, they converted both the Edgar Thomson Works and the Homestead Works to direct rolling. In 1892 Frick persuaded Carnegie to merge Carnegie Brothers and Carnegie , Phipps, Company into one vast company Carnegie Steel. It was formed on 1 July 1892 with a capitalization of $25,000,000 which was far below the actual value of the company. Carnegie owned 55%, Frick 11%, Phipps 1 1%, and nineteen other partners 1% each. The remaining 4% was held in re serve to reward successful young men in the plants. In 1901, Carnegie was 65 years old and was considering retirement. He reform ed his enterprises into conventional joint stock corporations as preparation to this end.

John Pierpont Morgan was a banker and perhaps America's most important fin ancial deal maker. He had observed how efficiency produced profit. He envi sioned an integrated steel industry that would cut costs, lower prices to consumers and raise wages to workers. To this end, he needed to buy out Ca rnegie and several other major producers and integrate them into one compa ny, thereby eliminating duplication and waste. Negotiations were concluded on March 2, 1901, with the formation of the United States Steel Corporati on. It was the first corporation in the world with a market capitalization in excess of US$1 billion.

The buyout, which was negotiated in secret by Charles M. Schwab (no relatio n to Charles R. Schwab, the brokerage house founder), was the largest such

industrial takeover in United States history to date. The holdings were inc orporated in the United States Steel Corporation, a trust organized by Morg an, and Carnegie retired from business. His steel enterprises were bought o ut at a figure equivalent to twelve times their annual earningsUS$480 mill ion [1]which at the time was the largest ever personal commercial transact ion. Andrew Carnegie's share of this amounted to US$225,639,000, which was paid to Carnegie in the form of 5%, 50 year gold bonds. The letter agreeing to sell his share was signed on February 26, 1901. On March 2, the circula r formally filing the organisation and capitalisation (at US$1,400,000,000 4% of U.S. national wealth at the time) of the United States Steel Corporat ion actually completed the contract. The bonds were to be delivered within two weeks to the Hudson Trust Company of Hoboken, New Jersey, in trust to R obert A. Franks, Carnegie's business secretary. There, a special vault was built to house the physical bulk of nearly US$230,000,000 worth of bonds. I t was said that "....Carnegie never wanted to see or touch these bonds that represented the fruition of his business career. It was as if he feared th at if he looked upon them they might vanish like the gossamer gold of the l eprechaun. Let them lie safe in a vault in New Jersey, safe from the New Yo rk tax assessors, until he was ready to dispose of them...." As they signed the papers of sale, Carnegie remarked, "Well, Pierpont, I a m now handing the burden over to you." In return, Andrew Carnegie became o ne of the world's wealthiest men.

By the time he died in 1919, he had given away $350,695,653 . At his death, the last $30,000,000 was likewise given away to foundations, charities an d to pensioners. Andrew Carnegie was convinced of and committed to the notion that educatio n was life's key. He was convinced of the power of, what we term today, ac cess to information. He learned that lesson profoundly in the libraries of Col. Anderson in Allegheny City. It was an experience he never forgot and which motivated his campaign of world-wide library-building. Over the doo rs of The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, carved in stone, are his own wor ds, "Free to the People."

You might also like

- HDFC Ergo Policy Renewal 2023 SelfDocument5 pagesHDFC Ergo Policy Renewal 2023 SelfGopivishnu KanchiNo ratings yet

- Inc42's Annual Indian Startup Funding Report 2021Document91 pagesInc42's Annual Indian Startup Funding Report 2021Ritik MehtaNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource WasDocument4 pagesThis Study Resource WasDerista septhiana100% (1)

- Gilded Age Essay-Mr. DeGarimoreDocument4 pagesGilded Age Essay-Mr. DeGarimoreandresgarza24No ratings yet

- Spiritual GiftsDocument7 pagesSpiritual GiftsyoyomamasanNo ratings yet

- Hedge Funds ProjectDocument8 pagesHedge Funds ProjectAyesha PattnaikNo ratings yet

- Andrew CarnegieDocument3 pagesAndrew CarnegiemrchiarielloNo ratings yet

- Iphone 6S Front-Facing Camera and Sensor Assembly ReplacementDocument18 pagesIphone 6S Front-Facing Camera and Sensor Assembly Replacementjoji ubasNo ratings yet

- Netscout Arbor Managed Services For Internet Service ProvidersDocument4 pagesNetscout Arbor Managed Services For Internet Service ProvidersEstebanChiangNo ratings yet

- Andrew CarnegieDocument6 pagesAndrew CarnegieQuirkyArtistNo ratings yet

- Andrew Carnegie - Part 1Document22 pagesAndrew Carnegie - Part 1Surbhit AhujaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 24 - Industry Comes of AgeDocument8 pagesChapter 24 - Industry Comes of AgeStephenPengNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurs and BankersDocument6 pagesEntrepreneurs and Bankersapi-326276148No ratings yet

- CHP 24 OutlineDocument3 pagesCHP 24 OutlineKingNico16No ratings yet

- Chapter 6:1 and 6:2 Notes: A. Setting The SceneDocument4 pagesChapter 6:1 and 6:2 Notes: A. Setting The SceneSamuel KulpNo ratings yet

- Business MonopolismDocument6 pagesBusiness Monopolismanuroopmishra10bNo ratings yet

- Andrew Carnegie - HISTORYDocument4 pagesAndrew Carnegie - HISTORYRedwanNo ratings yet

- JuliusDocument8 pagesJuliusAyuba Caleb MaduNo ratings yet

- Chapter 24 - Industry Comes of Age: I. The Iron Colt Becomes An Iron HorseDocument7 pagesChapter 24 - Industry Comes of Age: I. The Iron Colt Becomes An Iron Horsesymon08No ratings yet

- Samuel Lemoine - 14Document5 pagesSamuel Lemoine - 14api-692561635No ratings yet

- PHM - Clyde Engineering Photographic Collection Railway and Rolling StockDocument9 pagesPHM - Clyde Engineering Photographic Collection Railway and Rolling Stock4493464100% (1)

- Ensayo Sobre Andrew CarnegieDocument6 pagesEnsayo Sobre Andrew Carnegieyzfejshjf100% (1)

- America's History Chapter 17: Capital and Labor in The Age of EnterpriseDocument11 pagesAmerica's History Chapter 17: Capital and Labor in The Age of Enterpriseirregularflowers100% (2)

- History Periodic 2 Term 1Document6 pagesHistory Periodic 2 Term 1Dheekshithaa SaravananNo ratings yet

- CarnegieDocument9 pagesCarnegieSherren Marie NalaNo ratings yet

- ContentDocument8 pagesContentTuyetAnh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Railroads in America Promp EoyDocument4 pagesRailroads in America Promp Eoyapi-377050773No ratings yet

- Life in The Industrial AgeDocument11 pagesLife in The Industrial AgeHugo VillavicencioNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution in Britain HandoutDocument6 pagesIndustrial Revolution in Britain HandoutAlriNo ratings yet

- Industrialization in BritainDocument3 pagesIndustrialization in BritainSelsabil BnkNo ratings yet

- Chandler 1965Document25 pagesChandler 1965kikeirozNo ratings yet

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 4 "Carnegie Andrew" to "Casus Belli"From EverandEncyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 5, Slice 4 "Carnegie Andrew" to "Casus Belli"No ratings yet

- Revolution and The Rise of CapitalismDocument12 pagesRevolution and The Rise of Capitalismsharma mishraNo ratings yet

- Building The Transcontinental Railway FinalDocument21 pagesBuilding The Transcontinental Railway Finalapi-216487546No ratings yet

- Chapter 18Document18 pagesChapter 18ewrweNo ratings yet

- APUSH Chapter 24 NotesDocument8 pagesAPUSH Chapter 24 NotesphthysyllysmNo ratings yet

- Kitchen Rudders - Their Inventor and Some ApplicationsDocument22 pagesKitchen Rudders - Their Inventor and Some ApplicationsClyde Steamers100% (2)

- Aerial Mine Tramways in The WestDocument11 pagesAerial Mine Tramways in The Westicm1970No ratings yet

- Viebig 2019Document11 pagesViebig 2019Juan Diego Vega100% (1)

- Steam, Steel and Spark: The People and Power Behind the Industrial RevolutionFrom EverandSteam, Steel and Spark: The People and Power Behind the Industrial RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Chapter 24 APUSHDocument7 pagesChapter 24 APUSHCarolyn SabaNo ratings yet

- The Railway Navvies: A History of the Men who Made the RailwaysFrom EverandThe Railway Navvies: A History of the Men who Made the RailwaysRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Track Of The Ironmasters - A History Of The Cleator And Workington Junction RailwayFrom EverandThe Track Of The Ironmasters - A History Of The Cleator And Workington Junction RailwayNo ratings yet

- Andrew Carnegie Steel MagnateDocument1 pageAndrew Carnegie Steel MagnategeronimlNo ratings yet

- North Reading Set 2 Group BDocument2 pagesNorth Reading Set 2 Group Bapi-281321560No ratings yet

- 3B Power Point Prin of WalesDocument48 pages3B Power Point Prin of WalesCanada Railway TimesNo ratings yet

- Background InformationDocument2 pagesBackground Informationapi-256576265No ratings yet

- The Railroad Builders; a chronicle of the welding of the statesFrom EverandThe Railroad Builders; a chronicle of the welding of the statesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Carnegie BiographyDocument6 pagesCarnegie Biographyayax1No ratings yet

- Period 6 Part 1 1865-1898 Gilded Age Industrialization and PoliticsDocument12 pagesPeriod 6 Part 1 1865-1898 Gilded Age Industrialization and PoliticsIshaan DixitNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18, Section I: Miners, Ranchers, and RailroadsDocument3 pagesChapter 18, Section I: Miners, Ranchers, and Railroadsapi-264673293No ratings yet

- Unit 2 Big BusinessesDocument12 pagesUnit 2 Big BusinessesHIS22067 SUHANI TANDONNo ratings yet

- Robber Barons PP WipDocument12 pagesRobber Barons PP Wipapi-443864095No ratings yet

- Summary WorksheetDocument4 pagesSummary Worksheethridhaan.patel1702No ratings yet

- Milestones in the Mighty Age of Steam: The Grasshopper and the CorlissFrom EverandMilestones in the Mighty Age of Steam: The Grasshopper and the CorlissNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Gifts TestsDocument10 pagesSpiritual Gifts TestsOluwole Jedidiah OlusolaNo ratings yet

- Publication 2Document3 pagesPublication 2Oluwole Jedidiah OlusolaNo ratings yet

- The Marks of ManhoodDocument9 pagesThe Marks of ManhoodOluwole Jedidiah Olusola100% (1)

- Effective Presentations CareerDocument6 pagesEffective Presentations CareerOluwole Jedidiah OlusolaNo ratings yet

- The Research ProblemDocument67 pagesThe Research ProblemCj BeltranNo ratings yet

- Lesson 9: Front Office, Middle Office and Back OfficeDocument13 pagesLesson 9: Front Office, Middle Office and Back OfficePanes GrenadeNo ratings yet

- Central Government Role in Road Infrastructure Development and Economic Growth in The Form of Future Study: The Case of IndonesiaDocument12 pagesCentral Government Role in Road Infrastructure Development and Economic Growth in The Form of Future Study: The Case of IndonesiaRidho ridhoNo ratings yet

- Value Vs GrowthDocument2 pagesValue Vs Growthtdavis1234No ratings yet

- Instruction and Rubric ASSIGNMENT MAF661 Mar23-Aug23Document10 pagesInstruction and Rubric ASSIGNMENT MAF661 Mar23-Aug23Lyana InaniNo ratings yet

- Australasian Intercultural Cities Workshop Report 23 1 2019 FINAL PDFDocument11 pagesAustralasian Intercultural Cities Workshop Report 23 1 2019 FINAL PDFAAMIRNo ratings yet

- Sim Paper1 Ged105 A19Document6 pagesSim Paper1 Ged105 A19Arvee SimNo ratings yet

- Performance Evaluation of Square Textile Ltd. & Apex Spinning and Knitting Mills Ltd. Prepared ForDocument28 pagesPerformance Evaluation of Square Textile Ltd. & Apex Spinning and Knitting Mills Ltd. Prepared ForEnaiya IslamNo ratings yet

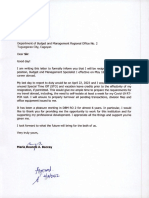

- Dbm-Roii-Letter of Resignation of MS Maria Roanne A BaccayDocument10 pagesDbm-Roii-Letter of Resignation of MS Maria Roanne A BaccayJale Ann A. EspañolNo ratings yet

- Wa0000Document4 pagesWa0000donimrlyNo ratings yet

- FTFCS 2022-03-23 1648030351701Document15 pagesFTFCS 2022-03-23 1648030351701Charles Goodwin100% (2)

- Employment LawDocument32 pagesEmployment LawniklynNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument5 pagesDocumentyogitaNo ratings yet

- Liability Insurance Certificate 2020Document2 pagesLiability Insurance Certificate 2020Majdi BelguithNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Opportunity Identification and SelectionDocument7 pagesChapter 3 Opportunity Identification and SelectionmanoNo ratings yet

- Bangko Sentral NG Pilipinas: History BSP Vision and Mission Overview of Functions and OperationsDocument17 pagesBangko Sentral NG Pilipinas: History BSP Vision and Mission Overview of Functions and OperationsMichelle GoNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior of The Selected Rizal Technological University Students During Covid-19 PandemicDocument7 pagesConsumer Behavior of The Selected Rizal Technological University Students During Covid-19 PandemicArsenio N. RojoNo ratings yet

- Customised Profit & Loss (Rs - in Crores) Mar 18 17-Mar 16-Mar 15-Mar 14-Mar 5,592.29 5,290.65 5,750.00 5,431.28 4,870.08Document20 pagesCustomised Profit & Loss (Rs - in Crores) Mar 18 17-Mar 16-Mar 15-Mar 14-Mar 5,592.29 5,290.65 5,750.00 5,431.28 4,870.08Akshay Yadav Student, Jaipuria LucknowNo ratings yet

- Metabical Case Study SolutionDocument7 pagesMetabical Case Study SolutionAshutosh PatkarNo ratings yet

- Revision NotesDocument51 pagesRevision NotesMelody RoseNo ratings yet

- Channels of Distribution: Conflict, Cooperation, and ManagementDocument23 pagesChannels of Distribution: Conflict, Cooperation, and ManagementskusonuNo ratings yet

- Fusion ProjectDocument118 pagesFusion ProjectankitdessoreNo ratings yet

- RSM 324 Notes 4Document103 pagesRSM 324 Notes 4xsnoweyxNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Managerial Economics Economics EssayDocument86 pagesThe Nature of Managerial Economics Economics EssayCoke Aidenry SaludoNo ratings yet

- 136024Document258 pages136024ssNo ratings yet

- 2022notice - MDF Email Submission 1Document1 page2022notice - MDF Email Submission 1ElaNo ratings yet