Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Memorandum - Richard Haste

Memorandum - Richard Haste

Uploaded by

Christopher RobbinsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Memorandum - Richard Haste

Memorandum - Richard Haste

Uploaded by

Christopher RobbinsCopyright:

Available Formats

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF BRONX: PART H60 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW

YORK,

-against-

Indictment No. 01822/2012

RICHARD HASTE, Defendant. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X

MEMORANDUM

ROBERT T. JOHNSON District Attorney Bronx County 198 East 161st Street Bronx, New York 10451 (718) 838-7053 JOSEPH N. FERDENZI STANLEY R. KAPLAN DONALD LEVIN Assistant District Attorneys Of Counsel

MAY 13, 2013

MEMORANDUM Defendants fellow officers made communications to defendant and other members of his SNEU team that they had observed Ramarley Graham with a gun, and they testified in the Grand Jury that they communicated those observations to defendant. Defendant, in turn, testified that, based upon those transmissions, he believed that Ramarley Graham had a gun all the while he pursued him and at the very moment he shot him. As it turned out, however, no gun was ever recovered from Ramarley Graham, nor was one recovered during a subsequent search of the premises and the adjacent areas. Accordingly, the danger existed that, had the Grand Jury found that the officers who made the erroneous communications to be incredible, there would be an adverse spillover effect on defendant because he relied on misinformation, and that the Grand Jury might find him to be unjustified on this basis alone. Hence, the following supplemental instructions were given by the prosecutor in an effort to prevent such prejudice to defendant. The prosecutor instructed, What controls here is not the reasonableness of the belief of other police officers or their communication to Police Officer Haste (MT17). This instruction was followed by, What controls here in the issue of justification is the reasonableness of Police Officer Hastes conduct at the time of the shooting that controls the issue in this case (MT17). This instruction was designed to apprise the Grand Jury that the reasonableness of the beliefs and the reasonableness of the consequent communications of these other officers to defendant were not the controlling factor. The prosecutor deliberately used the word control, which entails directing a result. The prosecutor could correctly instruct that whether communications from other officers were reasonable did not control or decide the issue of whether defendants own beliefs were reasonable and whether defendants conduct was justified. The meaning of this instruction becomes even more self-evident when a further instruction was given in response to a Grand Jurors question: It is not the reasonableness of the beliefs of other police officers that was communicated to Police Officer Haste that controls the issue of justification. It is the reasonableness of Police Officer Hastes conduct at the time of the shooting. That is the issue controls the issue of justification. (MT27)

This rephrasing of the instruction clearly established for the Grand Jury that the reasonableness standard applied to both the reasonableness of the belief of another officer and the reasonableness of the content of the communication of another officer to defendant. That this rephrasing proves that reasonableness modifies both clauses of the initial instruction is consistent 1

with ordinary grammatical rules. Regarding grammatical structure, the Ninth Circuit observed in Washington Educ. Assn v. Natl Right to Work Legal Def. Fund, 187 F. Appx 681, 682 (9th Cir. 2006), Under generally accepted rules of syntax, an initial modifier will tend to govern all elements in the series unless it is repeated for each element. The American Heritage Book of English Usage chapter 2, 10 (Houghton Mifflin, 1996),http://www.bartleby.com/64/2.html (last visited May 18, 2006); see United States Fid. & Guar. Co. v. Fireman's Fund Ins. Co., 896 F.2d 200, 203 (6th Cir.1990) (holding that the reasonable construction of the phrase negligent act, error, or omission is that the policy covers only negligent and not intentional conduct); Ward Gen. Ins. Servs., Inc. v. Employers Fire Ins. Co., 114 Cal.App.4th 548, 554, 7 Cal.Rptr.3d 844 (Cal.Ct.App.2003) (stating that [m]ost readers expect the first adjective in a series of nouns or phrases to modify each noun or phrase in the following series unless another adjective appears); Lewis v. Jackson Energy Coop. Corp., 189 S.W.3d 87, 92 (Ky. 2005) (stating that it is widely accepted that an adjective at the beginning of a conjunctive phrase applies equally to each object within the phrase. In other words, the first adjective in a series of nouns or phrases modifies each noun or phrase in the following series unless another adjective appears.). Concomitantly, it is evident that reasonableness, which modified belief, also modified communications. As a matter of rhetoric, the prosecutor omitted repetition of the word reasonableness for the sake of brevity since the repetition was as needless as repeating large in the sentence, He wanted a large truck or van, where large as the initial modifier applies to both truck and van. The only basis to find the instruction problematic would be if the prosecutor had plainly stated to the Grand Jury that communication from other officers could not be a factor in considering defendants state of mind. But, that is not what the prosecutor said. It would be unwarranted to conclude that the prosecutor instructed the Grand Jury to disregard what the fellow officers communicated to defendant. Indeed, the prosecutor repeatedly instructed the Grand Jury that it was to assess what a reasonable person would believe based upon what defendant knew (MT 15-16, 2123, 25-26). Obviously, what defendant knew included communications from other officers. The prosecutor never gave an instruction that was the opposite of that. Moreover, even if the initial instruction had any ambiguity, the response by the prosecutor to the Grand Juror, the last instruction heard by the Grand Jury, must be deemed to be the instruction upon which it relied (see Rock v. Coombe, 694 F.2d 908 [2d Cir. 1982] [significance of final instruction]), and dispelled any lack of clarity. See People v. Alvarez, 86 N.Y.2d 761, 763 (1995).

For a court to dismiss Grand Jury proceedings on the basis of instructions, such instructions must be so confusing and misleading as to substantially undermine the integrity of the proceedings. People v. Caracciola, 78 N.Y.2d 1021 (1991). Accordingly,[n]ot every omission or imprecision in the legal instruction impairs the integrity of the Grand Jury. People v. Torres, 252 A.D.2d 60, 67 (1st Dept. 1999). The supplemental instruction on justification cannot be considered so confusing and misleading as to affect the integrity of the proceedings, especially when viewed in the context of the entire charge on justification. It would indeed be ironic if an instruction designed to alleviate any prejudice to defendant arising from the testimony before the Grand Jury was read incorrectly to mean the opposite.

ROBERT T. JOHNSON District Attorney Bronx County

JOSEPH N. FERDENZI STANLEY R. KAPLAN DONALD LEVIN Assistant District Attorneys Of Counsel MAY 13, 2013

You might also like

- Gell, Alfred - Wrapping in ImagesDocument21 pagesGell, Alfred - Wrapping in ImagesCecilia100% (3)

- 2018.05.24 BerlinRosen Responsive Records PDFDocument4,251 pages2018.05.24 BerlinRosen Responsive Records PDFChris BraggNo ratings yet

- EXHIBIT 003A - NOTICE of Acceptance of OathDocument5 pagesEXHIBIT 003A - NOTICE of Acceptance of Oaththenjhomebuyer100% (1)

- Law of Torts 2018-1Document62 pagesLaw of Torts 2018-1navam singhNo ratings yet

- Richard Langone v. Harold J. Smith, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, 682 F.2d 287, 2d Cir. (1982)Document7 pagesRichard Langone v. Harold J. Smith, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, 682 F.2d 287, 2d Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Legal ArgumentDocument5 pagesHow To Write A Legal ArgumentReyhan Savero PradietyaNo ratings yet

- Robert Bumpus v. Frank Gunter, 635 F.2d 907, 1st Cir. (1980)Document11 pagesRobert Bumpus v. Frank Gunter, 635 F.2d 907, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tong v. State 25 S.W.3d 707 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000)Document13 pagesTong v. State 25 S.W.3d 707 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000)Legal KidNo ratings yet

- Life Music, Inc. v. Honorable David N. Edelstein, United States District Judge For The Southern District of New York, 309 F.2d 242, 2d Cir. (1962)Document3 pagesLife Music, Inc. v. Honorable David N. Edelstein, United States District Judge For The Southern District of New York, 309 F.2d 242, 2d Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Defense Reply For Summary JudgmentDocument15 pagesDefense Reply For Summary JudgmentThe Huntsville TimesNo ratings yet

- Benson v. Henkel, 198 U.S. 1 (1905)Document8 pagesBenson v. Henkel, 198 U.S. 1 (1905)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTION Criminal ProcedureDocument8 pagesINTRODUCTION Criminal ProcedureFelix BillsNo ratings yet

- Spurlock Reply Summary JudgmentDocument58 pagesSpurlock Reply Summary JudgmentThe Huntsville TimesNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In The United States District Court For The District of ColumbiaDocument12 pagesIn The United States District Court For The District of ColumbiaChrisNo ratings yet

- Lse - Ac.uk Storage LIBRARY Secondary Libfile Shared Repository Content Picinali, F Innocence and Burdens Picinali Innocence and Burdens 2014Document31 pagesLse - Ac.uk Storage LIBRARY Secondary Libfile Shared Repository Content Picinali, F Innocence and Burdens Picinali Innocence and Burdens 2014YugenndraNaiduNo ratings yet

- June 2, 2015: United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument21 pagesJune 2, 2015: United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitJohnnyLarsonNo ratings yet

- Sherry L. Houck v. City of Prairie Village, Kansas Barbara J. Vernon, 166 F.3d 1221, 10th Cir. (1998)Document8 pagesSherry L. Houck v. City of Prairie Village, Kansas Barbara J. Vernon, 166 F.3d 1221, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Estrada Vs SandiganbayanDocument9 pagesEstrada Vs SandiganbayanBetson CajayonNo ratings yet

- James Battaglia, Libelant-Appellant v. United States, 303 F.2d 683, 2d Cir. (1962)Document5 pagesJames Battaglia, Libelant-Appellant v. United States, 303 F.2d 683, 2d Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- ASTHA Contracts IIDocument20 pagesASTHA Contracts IIHONEYNo ratings yet

- United States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583, 2d Cir. (1952)Document35 pagesUnited States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583, 2d Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rodney Francis King v. Larry Fields Delores Ramsey John Middleton David Arneecher, 145 F.3d 1345, 10th Cir. (1998)Document3 pagesRodney Francis King v. Larry Fields Delores Ramsey John Middleton David Arneecher, 145 F.3d 1345, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ken Roy Backas A/K/A James Smith, 901 F.2d 1528, 10th Cir. (1990)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Ken Roy Backas A/K/A James Smith, 901 F.2d 1528, 10th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Goldsmith SykesDocument11 pagesGoldsmith SykesPulkit PareekNo ratings yet

- United States v. James Rufus Davis, 328 F.2d 864, 2d Cir. (1964)Document4 pagesUnited States v. James Rufus Davis, 328 F.2d 864, 2d Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Medina-Silverio, 30 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1994)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Medina-Silverio, 30 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 (1964)Document19 pagesGarrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. Kelly Wilson v. The Hon. Daniel McMann Warden, Clinton State Prison, Dannemora, N.Y., 408 F.2d 896, 2d Cir. (1969)Document5 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. Kelly Wilson v. The Hon. Daniel McMann Warden, Clinton State Prison, Dannemora, N.Y., 408 F.2d 896, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joseph T. Lorenz, Jr. v. CSX Transportation, Incorporated, 980 F.2d 263, 4th Cir. (1993)Document13 pagesJoseph T. Lorenz, Jr. v. CSX Transportation, Incorporated, 980 F.2d 263, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Rone, 10th Cir. (2003)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Rone, 10th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Thomas McCabe v. Daniel Rattiner, 814 F.2d 839, 1st Cir. (1987)Document6 pagesThomas McCabe v. Daniel Rattiner, 814 F.2d 839, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Mark Jessup, 757 F.2d 378, 1st Cir. (1985)Document30 pagesUnited States v. Mark Jessup, 757 F.2d 378, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument10 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Murray L. Petersen v. United States, 268 F.2d 87, 10th Cir. (1959)Document6 pagesMurray L. Petersen v. United States, 268 F.2d 87, 10th Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Louis Nathan Ray, 931 F.2d 64, 10th Cir. (1991)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Louis Nathan Ray, 931 F.2d 64, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Washington Law Review Washington Law Review: Degrees of Secondary Evidence Degrees of Secondary EvidenceDocument14 pagesWashington Law Review Washington Law Review: Degrees of Secondary Evidence Degrees of Secondary EvidenceSwati PandaNo ratings yet

- Rem 2 AssignmentDocument3 pagesRem 2 AssignmentJeffrey MagadaNo ratings yet

- PLJ Volume 39 Number 2 - 04 - Arturo v. Parcero & Rodolfo G. Urbiztondo - EvidenceDocument19 pagesPLJ Volume 39 Number 2 - 04 - Arturo v. Parcero & Rodolfo G. Urbiztondo - EvidenceAlbert RoñoNo ratings yet

- Stephen L. Stringfellow v. Jesse Brown, Secretary of The Veterans Administration, 105 F.3d 670, 10th Cir. (1997)Document4 pagesStephen L. Stringfellow v. Jesse Brown, Secretary of The Veterans Administration, 105 F.3d 670, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument4 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Alan Lloyd Lussier v. Frank O. Gunter, 552 F.2d 385, 1st Cir. (1977)Document6 pagesAlan Lloyd Lussier v. Frank O. Gunter, 552 F.2d 385, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Richard Roe, Inc., and John Doe, Inc. United States of America v. Richard Roe, Inc., Richard Roe, John Doe, Inc., and John Doe, 68 F.3d 38, 2d Cir. (1995)Document5 pagesIn Re Richard Roe, Inc., and John Doe, Inc. United States of America v. Richard Roe, Inc., Richard Roe, John Doe, Inc., and John Doe, 68 F.3d 38, 2d Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument6 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Law of EvidencefinalDocument20 pagesLaw of Evidencefinalarlyn georgeNo ratings yet

- Robinson v. City and County, 10th Cir. (2001)Document4 pagesRobinson v. City and County, 10th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joe Pepe, 501 F.2d 1142, 10th Cir. (1974)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Joe Pepe, 501 F.2d 1142, 10th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Castellanos, 10th Cir. (2006)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Castellanos, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ronald E. Henderson v. Inter-Chem Coal Co., Inc. Nationwide Mining, Inc., A Kansas Corporation and Brent Nations, 41 F.3d 567, 10th Cir. (1994)Document5 pagesRonald E. Henderson v. Inter-Chem Coal Co., Inc. Nationwide Mining, Inc., A Kansas Corporation and Brent Nations, 41 F.3d 567, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United State of America v. Dennis Bates Fletcher, 25 F.3d 1058, 10th Cir. (1994)Document6 pagesUnited State of America v. Dennis Bates Fletcher, 25 F.3d 1058, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Charles D. Bonanno Linen Service, Inc. v. William J. McCarthy, 532 F.2d 189, 1st Cir. (1976)Document4 pagesCharles D. Bonanno Linen Service, Inc. v. William J. McCarthy, 532 F.2d 189, 1st Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Spencer, 10th Cir. (2010)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Spencer, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nixon v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2002)Document5 pagesNixon v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mandel v. Boston Phoenix Inc., 456 F.3d 198, 1st Cir. (2006)Document15 pagesMandel v. Boston Phoenix Inc., 456 F.3d 198, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gerald K. Adamson, Plaintiff-Appellant/cross-Appellee v. Otis R. Bowen, M.D., Secretary of Health & Human Services, Defendant - Appellee/cross-Appellant, 855 F.2d 668, 10th Cir. (1988)Document14 pagesGerald K. Adamson, Plaintiff-Appellant/cross-Appellee v. Otis R. Bowen, M.D., Secretary of Health & Human Services, Defendant - Appellee/cross-Appellant, 855 F.2d 668, 10th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Helen L. Seymour v. Parke, Davis & Company, 423 F.2d 584, 1st Cir. (1970)Document5 pagesHelen L. Seymour v. Parke, Davis & Company, 423 F.2d 584, 1st Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. John R. Barletta, 652 F.2d 218, 1st Cir. (1981)Document4 pagesUnited States v. John R. Barletta, 652 F.2d 218, 1st Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument15 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument10 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chiquita Supplement Re Hearsay Exceptions in Summary JudgmentDocument25 pagesChiquita Supplement Re Hearsay Exceptions in Summary JudgmentPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- Harvard Law Review: Volume 131, Number 2 - December 2017From EverandHarvard Law Review: Volume 131, Number 2 - December 2017No ratings yet

- U.S. v. Orlando DennisDocument20 pagesU.S. v. Orlando DennisChristopher Robbins100% (1)

- Camoin 310 Report 2019 20 Film Incentive Impact ESD FinalDocument34 pagesCamoin 310 Report 2019 20 Film Incentive Impact ESD FinalChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- MDC Class Action LawsuitDocument32 pagesMDC Class Action LawsuitChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- E-Bike Patrol Guide MemoDocument4 pagesE-Bike Patrol Guide MemoChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- New York City Borough-Based Jail System Draft Scope of Work To Prepare A Draft Environmental Impact StatementDocument56 pagesNew York City Borough-Based Jail System Draft Scope of Work To Prepare A Draft Environmental Impact StatementChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Canarsie Tunnel Repairs: Planning Ahead For The CrisisDocument5 pagesCanarsie Tunnel Repairs: Planning Ahead For The CrisisChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Federal Lawsuit Against NYC by Airbnb UserDocument21 pagesFederal Lawsuit Against NYC by Airbnb UserChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Rep menglettertoNYSDMV11!17!14Document1 pageRep menglettertoNYSDMV11!17!14Christopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Fliedner ComplaintDocument63 pagesFliedner ComplaintChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Spinelli v. NYCDocument19 pagesSpinelli v. NYCChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- U.S. V Deiban Et Al IndictmentDocument10 pagesU.S. V Deiban Et Al IndictmentChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Brian Coll & Byron Taylor Criminal ComplaintDocument26 pagesBrian Coll & Byron Taylor Criminal Complainttom clearyNo ratings yet

- Ows First Amendment SuitDocument41 pagesOws First Amendment SuitChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Plaintiffs' Letter Re Destroyed Evidence in Stinson TrialDocument15 pagesPlaintiffs' Letter Re Destroyed Evidence in Stinson TrialChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- NYPIRG Gov Fundraising 10 7 2014Document11 pagesNYPIRG Gov Fundraising 10 7 2014Christopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- OWS Media Group Inc V Wedes - Verified ComplaintDocument9 pagesOWS Media Group Inc V Wedes - Verified ComplaintChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Brief NYPD Body Worn Cameras FinalDocument19 pagesBrief NYPD Body Worn Cameras FinalChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- The Countering Reference To The False Report Regarding Kum Kang SanDocument5 pagesThe Countering Reference To The False Report Regarding Kum Kang SanChristopher RobbinsNo ratings yet

- NYPIRG Casino MoneyDocument15 pagesNYPIRG Casino MoneyjodatoNo ratings yet

- Estrada V SandiganbayanDocument6 pagesEstrada V SandiganbayanMp CasNo ratings yet

- Marcos Vs Sandiganbayan, GR No 126995Document57 pagesMarcos Vs Sandiganbayan, GR No 126995Add AllNo ratings yet

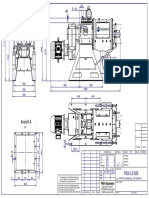

- PSS 3.2 - 520 - 5,5kW - DrawingDocument1 pagePSS 3.2 - 520 - 5,5kW - DrawingCentrifugal SeparatorNo ratings yet

- 18-Ludo and Lu Ym Corporation v. Aznar Brothers Realty Co. G.R. No. 143307 April 26, 2006Document8 pages18-Ludo and Lu Ym Corporation v. Aznar Brothers Realty Co. G.R. No. 143307 April 26, 2006Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Douglas Crucey, A043 446 797 (BIA June 12, 2017)Document20 pagesDouglas Crucey, A043 446 797 (BIA June 12, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- 22, Judicial AdministrationDocument31 pages22, Judicial Administrationajay narwalNo ratings yet

- The Law in ZimbabweDocument28 pagesThe Law in ZimbabwemandlenkosiNo ratings yet

- Accountability Hub Investigative JournalismDocument1 pageAccountability Hub Investigative JournalismJohn Richard Kasalika100% (1)

- Life After Prison Steps To Making It On The OutsideDocument9 pagesLife After Prison Steps To Making It On The Outsideemail1636100% (2)

- Employee Bio-Data: Punjab National BankDocument3 pagesEmployee Bio-Data: Punjab National BankSanket LoharNo ratings yet

- People Vs AncajasDocument7 pagesPeople Vs AncajasShane Fernandez JardinicoNo ratings yet

- Unsolved Mystery 1Document9 pagesUnsolved Mystery 1api-332967216No ratings yet

- Cosep v. PEO 290 SCRA 378Document1 pageCosep v. PEO 290 SCRA 378Eu CaNo ratings yet

- SlavFile, The American Translators Assoc. Slavic Languages Division's NewsletterDocument21 pagesSlavFile, The American Translators Assoc. Slavic Languages Division's NewsletterLukaszCudnyNo ratings yet

- Sanshin CaseDocument7 pagesSanshin Caselakshmimenon39No ratings yet

- Asetre vs. AsetreDocument15 pagesAsetre vs. AsetreAlexandra Nicole SugayNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Department Staffing - McCabeDocument26 pagesAnalysis of Department Staffing - McCabeHOONG123No ratings yet

- United States v. David P. Twomey, 845 F.2d 1132, 1st Cir. (1988)Document6 pagesUnited States v. David P. Twomey, 845 F.2d 1132, 1st Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Death Penalty SpeechDocument2 pagesDeath Penalty SpeechHamza BerradaNo ratings yet

- Political Law ReviewDocument64 pagesPolitical Law Reviewdenbar15No ratings yet

- Robert Joyner White v. United States, 279 F.2d 740, 4th Cir. (1960)Document14 pagesRobert Joyner White v. United States, 279 F.2d 740, 4th Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Petition For InjunctionDocument9 pagesPetition For InjunctionCircuit MediaNo ratings yet

- The Proceeds of Crime and Anti Money Laundering Bill 2008Document137 pagesThe Proceeds of Crime and Anti Money Laundering Bill 2008cyruskuleiNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Court Appearances and Procedure Prior To Trial in HKDocument15 pagesPreliminary Court Appearances and Procedure Prior To Trial in HKwang_chan_7No ratings yet

- REQUEST For DELIVERY WITHOUT THE ORIGINAL BILL of LADING's (DELAYED)Document2 pagesREQUEST For DELIVERY WITHOUT THE ORIGINAL BILL of LADING's (DELAYED)Sunil Ranjan MohapatraNo ratings yet

- In Re Emil Jurado (1995)Document8 pagesIn Re Emil Jurado (1995)UP LAW100% (3)

- Legree v. Kent County Sheriff&apos S Department - Document No. 6Document14 pagesLegree v. Kent County Sheriff&apos S Department - Document No. 6Justia.comNo ratings yet